Double Dualism, Economic Growth Slowdown, and Falling Income Inequality in Thailand

Abstract

Thailand has experienced a decline in income inequality coupled with unimpressive economic growth since the end of the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis. This paper uses the structuralist approach to understand how these concurrent economic phenomena have become deeply intertwined. We argue that this intertwining results from Thailand’s economic structure, manifesting two types of dualism: (i) the dualism of the formal–informal sectors and (ii) the dualism of the dynamic–stagnant sectors. A decline in the informal sector in recent years coincides with a decrease in income inequality. Further, the second type of dualism between the dynamic and stagnant sectors has emerged since 2000. The stagnant sectors’ employment share has grown faster than that of the dynamic sectors, resulting in a slowdown in economic growth and less inequality. The decline of the informal sector and the rise of the stagnant sectors are the primary engines weighing down economic growth and reducing income inequality in Thailand.

I. Introduction

Thailand’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita growth averaged 7.1% during 1985–1996, 4.5% during 2000–2007, and 3.2% during 2010–2019. As a result of the declining trend in economic growth, many scholars proposed that the country had fallen into the so-called “middle-income trap” (see, for example, Warr 2011, Jitsuchon 2012, Doner and Schneider 2016, Kanchoochat 2018, Satitniramai 2019, and Suehiro 2019). Meanwhile, the income gap has dramatically widened compared to other countries in the same region, and this inequality has significantly impacted the economic, social, and political aspects of the Thai people’s everyday lives (see, for example, Hewison 2014, Phongpaichit 2016, and Phongpaichit and Baker 2016). Using an income-based Gini coefficient, Thai inequality was 0.45 in 2015, ranking the country in the third quartile in the world but the highest in Southeast Asia (Yang, Wang, and Dewina 2020, p. 20). However, several studies have confirmed that although income inequality in Thailand increased before the 1990s, it has decreased since the late 1990s, conforming to the inverted U-shaped Kuznets curve (see, for example, Jeong 2008 and Warr and Suphannachart 2020). Whether inequality is based on income, consumption, or wealth, the trend has conclusively declined since the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis (AFC) (Lekfuangfu et al. 2020). In the global context, Thailand was the only Asian country among 18 developing countries worldwide that experienced robustly declining inequality after the AFC, with a fall in the Gini coefficient of more than 3 percentage points over 5 years or more (Simson and Savage 2020).1

Declining income inequality should not be considered the sole indicator of a healthy Thai economy. For instance, Kanchoochat (2023) provided an institutional view of why the declining trend of Thailand’s income inequality can be a false positive as the economy is still stuck at the “low-road” equilibrium, where most people are still working in the low-productivity agriculture sector. In this paper, we propose that, based on the structuralist approach, Thailand has experienced a double dualism in its economic sectors: (i) dynamic–stagnant dualism and (ii) formal–informal dualism. This double dualism has caused the Thai economy to experience sluggish economic growth, a slowdown in structural transformation, and high (yet declining) income inequality.

For the first type of dualism, we categorize economic activities into two main types of sectors, either dynamic or stagnant, based on the labor productivity level. Dynamic sectors include mining, manufacturing, utilities, transport services, business services, financial services, and real estate. Stagnant sectors include construction, trade services, government services, and other services. We find that after the end of the AFC, the employment share of the stagnant sectors increased faster than that of the dynamic sectors, which implies that the stagnant sectors have become the employment engine of the economy. The result has been slow economic growth and regressive structural transformation.

The second dualism is that between formal and informal sectors. In the Republic of Korea, Koo (2021) argued that income distribution has become polarized in two forms: (i) between regularly employed and non-regularly employed workers, and (ii) between the top 10% and the rest of the workforce. These structural cleavages in the labor market in the Republic of Korea caused an increase in income inequality that was structurally different from the Western rich countries. Along the same lines, we show that the employment share of the informal sector in Thailand is immense, with a significant wage gap between formal and informal workers. As a result, with more than half of the labor force working in the informal sector, this dichotomy plays a vital role in keeping income inequality high in terms of absolute inequality levels in Thailand compared to inequality in other East and Southeast Asian countries.

The interplay of double dualism described above can explain the declining trend of income inequality in the past decade in two ways. First, a rise in the stagnant sector employment share mobilizes labor from agriculture, a sector with the lowest productivity and wages, to nonagricultural stagnant sectors with higher productivity and wages. The rise of stagnant sectors decreases income inequality by turbocharging the income of the bottom 50%. However, with this regressive structural transformation, economic growth is slower than before because the dynamic sectors have not been the main employment engine, which explains why Thailand has simultaneously experienced slow economic growth and declining income inequality. Second, a fall in employment in the informal sector, especially in agriculture and trade services, is another factor that has decreased income inequality in Thailand. With more people relocating jobs from the informal to formal sector—a process that we interpret as progressive structural transformation—the gap in total income between formal and informal laborers has become narrower.

This paper is divided into six sections. Section II details the rise and fall of income inequality in Thailand, the social and political context behind such developments, and debates concerning the causes of significant (but slow) declining income equality in the country. Section III adopts the concept of dynamic–stagnant sectors to analyze the first dualism of the Thai economy. Since the mid-1990s, the stagnant sectors have grown faster than the dynamic sectors, leading to sluggish economic growth. However, this trend reduces income inequality since labor mobilizes from agriculture, the sector with the lowest wages, to stagnant sectors with higher wages. Section IV investigates the second dualism between the formal and informal sectors. Thailand’s informal economy is large compared with other countries in the same region. Because informal employees receive significantly less than their formal colleagues, this wage gap contributes to high income inequality in Thailand. A decline of the informal sector’s employment share in recent years coincides with a decline in income inequality. Section V provides a regression analysis of the relationship between income inequality and double dualism. The results confirm that (i) the size of the informal economy is positively correlated with income inequality, and (ii) the size of the stagnant sectors is negatively correlated with income equality. Section VI concludes our findings, which substantiate our argument that double dualism can explain the dynamics of income inequality and economic growth in Thailand.

II. Thailand’s Income Inequality

A. Income Inequality in Thailand, 1980–2020

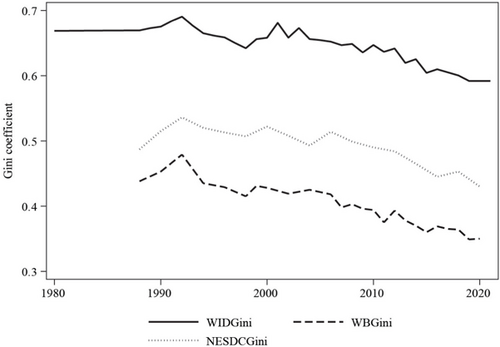

We obtained Thailand’s Gini coefficient from three sources from 1980 to 2021: (i) the World Inequality Database (WID),2 (ii) Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) of Thailand,3 and (iii) the World Bank4 (Figure 1). All three series show income inequality increased and peaked around the mid-1990s, then declined after the AFC. These figures are consistent with Motonishi (2006), who reported that income inequality in Thailand increased during 1975–1998. Townsend (2011) also found that the Gini coefficient rose from 0.436 in 1976 to 0.535 in 1992, and it fell to 0.511 by 1996. Zhuang (2023) summarized the trend of income inequality in Asia and confirmed that income inequality in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand has declined since the 1990s.

Figure 1. Thailand’s Gini Coefficients, 1980–2020

Sources: World Bank. World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed 24 July 2022); World Inequality Lab. World Inequality Database. https://wid.world/ (accessed 24 July 2022); Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) of Thailand. Poverty and Income Inequality Statistics. https://www.nesdc.go.th/main.php?filename=PageSocial (accessed 24 July 2022).

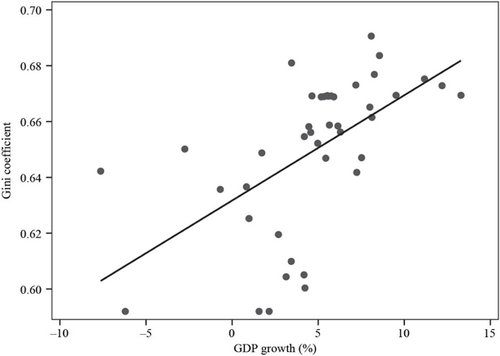

Kuznets (1955) stated that as the income of developing countries increases, the level of income inequality is expected to increase before it declines at the turning point, showing an inverted U-shaped relationship. In Thailand, the relationship between GDP growth and the Gini coefficient showed a positive trend from 1980 to 2021 (Figure 2). Ikemoto and Uehara (2000) examined whether Thailand had passed the turning point on the Kuznets curve and explained that income inequality increased rapidly in the latter half of the 1980s. They argued that the disparity did not show a clear decreasing trend in the 1990s as the Thai economy shifted to a domestic orientation.

Figure 2. Scatterplot between Thailand’s Income Inequality and Gross Domestic Product Growth, 1980–2021

GDP=gross domestic product. Notes: Trend line equation is Gini=0.63+0.004×(GDP growth). R-squared=0.33.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on (i) World Bank. World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed 24 July 2022); and (ii) World Inequality Lab. World Inequality Database. https://wid.world/ (accessed 24 July 2022).

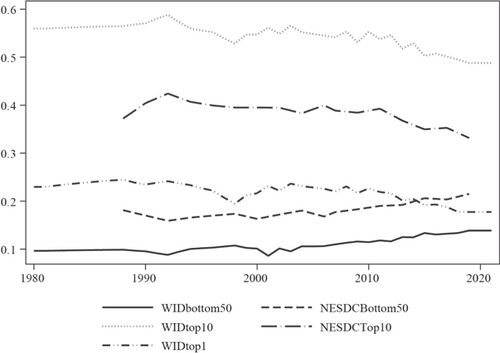

The decreasing inequality trend emerged during the late 1990s (i.e., after the AFC). The main contribution to this change was the rising income share of the bottom 50%. Figure 3 plots the income shares of the bottom 50%, top 10%, and top 1% of income earners from 1980 to 2020. We compared the data from two sources: NESDC and the World Inequality Database. The data show that the income share of the bottom 50% was constant before 2000 and has increased since 2004. The income shares of the top 10% and top 1% also slightly dropped, but this trend became apparent only after 2010.

Figure 3. Income Shares of Different Deciles, 1980–2021

Sources: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) of Thailand. Poverty and Income Inequality Statistics. https://www.nesdc.go.th/main.php?filename=PageSocial (accessed 24 July 2022); World Inequality Lab. World Inequality Database. https://wid.world/ (accessed 24 July 2022).

B. Some Caveats on Decreasing Income Inequality

The fact that between 1980 and 2021 the Gini coefficient decreased and the income share of the bottom 50% rose could be a good sign for Thailand’s economic development and income distribution. However, there are many precautions hidden inside the good-looking figures. Although the Gini coefficient decreased slightly, the absolute value of the coefficient is still at a higher level compared to other countries in the same income range and region.

Table 1 shows the Gini coefficient and the bottom 50% income share among members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In 2018, while the Philippines was considered the most unequal country in the region according to the World Development Indicators, Thailand’s Gini index stood fourth among ASEAN countries. The income share of the bottom 50% of income earners in Thailand in 2021 was only higher than the bottom 50% in Cambodia, Indonesia, and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, among other ASEAN members.

| Bottom 50% Income Share in 2021 | Gini Coefficient in 2021 (World Inequality Database) | Gini Coefficient in 2021 (WDI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 0.1239 | 0.60 (2018) | 0.378 (2018) |

| Lao PDR | 0.1284 | 0.60 (2018) | 0.388 (2018) |

| Cambodia | 0.1386 | 0.58 (2018) | 0.357 (2018) |

| Thailand | 0.1389 | 0.60 (2018) | 0.364 (2018) |

| Philippines | 0.1432 | 0.57 (2018) | 0.423 (2018) |

| Viet Nam | 0.1458 | 0.56 (2018) | 0.357 (2018) |

| Myanmar | 0.1593 | 0.54 (2018) | 0.307 (2017) |

| Singapore | 0.1665 | 0.55 (2018) | NA |

| Malaysia | 0.1730 | 0.52 (2018) | 0.411 (2015) |

| Brunei Darussalam | 0.1922 | 0.48 (2018) | NA |

The Gini coefficients obtained from the WID are consistent with the other two series. It shows that Thailand was among the top four countries in the ASEAN in terms of income inequality (0.60) in 2021. In sum, although the inequality trend is declining, the level of Thailand’s inequality is still relatively high, and the income share of the bottom 50% is relatively low compared to other countries in ASEAN.

Recent studies have pointed out that Thailand’s inequality data, including its Gini coefficient, are problematic and tend to be underestimated. Lekfuangfu et al. (2020) found that the decline in income inequality among the oldest households was primarily driven by private transfers because the heads of the households were inactive in the labor market. The inequality among active households rose in families earning income from farming activities. Thailand’s low-income families are still susceptible to income shocks, and their income includes a significant share from government transfers. Wasi et al. (2019) found that the median wage gap between college and noncollege workers continued to grow during 1988–2017. Sudswong, Plangprasopchok, and Amornbunchornvej (2021) analyzed a survey of incomes and occupations from more than 12 million households in Thailand and argued that the Gini coefficient alone overlooks the occupational heterogeneity, resulting in missing undetected patterns of inequality, especially among the lowest income groups.

Gini coefficients calculated from socioeconomic surveys are also underestimated. No data are available for the top 5% and 1% of income earners, and the survey had no income category higher than 100,000 baht (B) per month. Moreover, if tax data were included, the Gini coefficient would be higher (Jenmana 2018, Vanitcharearnthum 2019). Even though overall income inequality dropped after 2000, income growth was almost erased from 2015 to 2018, with more significant declines among households at the bottom (Yang, Wang, and Dewina 2020), primarily due to the fall in agricultural prices. Growth across geographic regions is also uneven. Household consumption growth was more damaging for those at the lower deciles than at the top in the central and northern regions.

Income inequality in Thailand is also the result of a long-term political and economic process that has unevenly benefited the top-income groups living in urban areas, particularly in Bangkok. The benefits of economic growth between the 1960s and the 1980s were concentrated in large enterprises, export industries, and the banking sector (Jenmana and Gethin 2019). The Gini index is often insufficient to understand the complexity of the inequality problem inherited from Thailand’s highly unequal social structure and political conflicts. In the following sections, we propose another economic dimension that contributes to the interplay between economic growth and income inequality in Thailand: double dualism.

III. Dualism between Dynamic and Stagnant Sectors

A. Industrialization in Thailand: Unfinished Business?

Economic activities can be separated into 12 economic sectors according to the United Nations’ ISIC Rev. 4 (Table 2). Structuralist economics holds that the dynamics of the economic structure can determine both economic growth and development. Kaldor (1966) proposed that there is a strongly positive long-run relationship between industrial output growth and nonindustrial output growth. Industrialization is therefore a driver of economic growth in most developing countries as workers move from low-productivity sectors, often agriculture, toward high-productivity sectors, usually manufacturing and advanced services (see, for example, Pieper 2003; Felipe et al. 2007; and McMillan, Rodrik, and Verduzco-Gallo 2014). From the point of view of income distribution, the development of a modern sector requires policies that favor business (e.g., tax rebates for investment, cheap loans for targeted industries) rather than labor. Therefore, early industrializers may encounter rising income inequality, conforming to the first phase of the Kuznets curve.

| ISIC Rev. 4 Code | ETD Sector | ISIC Rev. 4 Description |

|---|---|---|

| A | Agriculture | Agriculture, forestry, fishing |

| B | Mining | Mining and quarrying |

| C | Manufacturing | Manufacturing |

| D+E | Utilities | Electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply; water supply; sewage, waste management, and remediation activities |

| F | Construction | Construction |

| G+I | Trade services | Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles, accommodation and food service activities |

| H | Transport services | Transportation and storage |

| J+M+N | Business services | Information and communication; professional, scientific, and technical activities; administrative and support service activities |

| K | Financial services | Financial and insurance activities |

| L | Real estate | Real estate activities |

| O+P+Q | Government services | Public administration and defense, compulsory social security, education, human health and social work activities |

| R+S+T+U | Other services | Arts, entertainment, and recreation; other service activities; activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods- and services-producing activities of households for own use; activities of extraterritorial organizations and bodies |

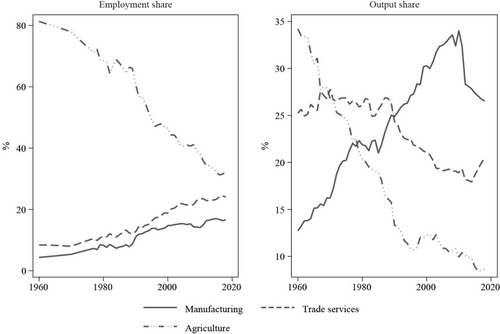

Based on the University of Groningen’s Economic Transformation Database (Kruse et al. 2022), Figure 4 shows the employment and output shares from the top three economic sectors in Thailand—agriculture, manufacturing, and trade services—from 1960 to 2018. Agricultural employment and output shares consistently fell from the 1960s during the process of rapid industrialization, as observed in other East Asian newly industrializing countries. Agricultural output as a share of GDP fell from 34.2% in 1960 to only 8.7% in 2018. Agricultural employment significantly decreased from 81.3% in 1960 to only 32.2% in 2018. Meanwhile, the manufacturing sector gained in terms of both output share (from 13% in 1960 to 27% in 2018) and employment share (from 4% in 1960 to 17% in 2018). Trade services also gained significantly in terms of employment share, rising from 8% in 1960 to 24% in 2018. However, in terms of output share, trade services peaked in 1987 at 27% and fell to 18% in 2014. Interestingly, the gap in employment share between manufacturing and trade services seemed to increase, especially after the AFC. In other words, Thailand’s trade services have created jobs faster than manufacturing since the 2000s. This structural shift has significantly contributed to economic growth and income inequality.

Figure 4. Employment and Output Shares, 1960–2018

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Groningen Growth and Development Center’s UNU-WIDER Economic Transformation Database (Kruse et al. 2022).

The increasing gap between manufacturing and trade services indicates that Thailand’s slowdown in industrialization coincided with slow economic growth or the so-called middle-income trap. Following Kaldor’s laws, any country with a slowdown in industrialization will also experience a slowdown in economic growth. Both phenomena are highly correlated. Felipe, Mehta, and Rhee (2019) showed that all rich, non-oil exporting countries today have achieved at least 18% manufacturing employment in the past. Thailand’s manufacturing employment slowly grew in the past decade and peaked at about 17% in 2015. What is more concerning is that the manufacturing value-added share declined after 2011. Figure 4 shows manufacturing value added peaked in 2010 at 30.0% and then decreased to 26.5% in 2018. This trend may resemble premature deindustrialization, or when the output and employment shares of manufacturing peak at lower levels than they did in high-income precursors (see, for example, Dasgupta and Singh 2007; Rodrik 2016; Tregenna 2016; Atolia et al. 2020; and Nayyar, Cruz, and Zhu 2021). Most research excluded Thailand from the list of countries experiencing premature deindustrialization. For instance, Ravindran and Babu (2023) used five conditions based on the trends in value-added and employment shares of manufacturing. Their study identified 32 middle-income countries that satisfy all conditions. The list includes only four countries from Asia: Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, and Pakistan. Thailand, however, is not on the list.

The significance of the manufacturing sector does not mean that the structural transformation of service sectors is always inefficient or slows down economic growth. Some studies have shown that certain service sectors can be dynamic and have a significantly positive impact on long-term productivity and economic growth. For instance, Di Meglio et al. (2018) provided an excellent review of, and tests on, Kaldor’s laws for 29 developing economies in Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa between 1975 and 2005. They showed that manufacturing and business services positively impact aggregate productivity growth, whereas other services slow down economic growth and labor productivity. Therefore, business services can bolster structural transformation of the core manufacturing activities since they contribute to knowledge spillovers and accumulation, and require highly skilled human capital (Gallego and Maroto 2015). However, Thailand’s structural change has not shown a rise in business services but rather a rise in trade services. As Figure 4 shows, as the gap in employment shares between trade services and manufacturing became larger, trade services steadily declined in their value-added share from 22.5% in 1990 to 20.5% in 2018. In other words, the sector that significantly created jobs in the past decade is not the most dynamic or growth-enhancing sector (i.e., manufacturing or business services) but rather a growth-retarding sector such as trade services.

B. Dualism: Old and New

For structuralist economics, the goal of economic development is “the structural transformation of underdeveloped economies in such a way as to permit a process of self-sustained economic growth more or less along the lines of today’s industrially advanced countries” (Hunt 1989, p. 50). Arthur Lewis’ model was classified as an early structuralist work that aimed to understand developing countries’ unique preconditions of development (Chenery 1975). In the original paper, Lewis (1954) described the process of economic development as labor and production reoriented from the traditional sector (e.g., agriculture, rural, informal, and basic services) to the modern sector (e.g., manufacturing, urban, formal, and advanced services). During this process, wages can be stagnant due to a surplus of labor until a certain point at which labor in rural areas is depleted and wages begin to increase—the so-called Lewis turning point. Dualism is therefore used to explain the in-between process when the labor market is dichotomized into modern and traditional sectors.

The framework of dualism has made a comeback. Storm (2017), Temin (2018), and Taylor and Ömer (2019) revived the idea of dualism to explain the United States’ economy in the past few decades. Using labor productivity and its growth level as a benchmark, they showed that the United States experienced a dual economy that dichotomizes the labor market into the dynamic sectors, where productivity and wages are high, and the stagnant sectors, where productivity and wages are low. Temin (2018) included finance, technology, and electronics in the dynamic sectors, while the stagnant sectors included the rest. In Taylor and Ömer (2019), the dynamic sectors comprise manufacturing, information, finance, mining, retail, wholesale, agriculture, and utilities, while all others fall into the stagnant sectors. Storm (2017) categorized manufacturing, information, finance, real estate, and business services as the dynamic sectors, while the remaining are stagnant. All three studies found a widening gap between the dynamic and stagnant sectors regarding labor productivity, income, and employment. While the stagnant sectors showed growing employment but zero productivity growth, the dynamic sectors manifested higher labor productivity but declining employment. Storm (2017) found that, in the 1950s, the employment share of the dynamic sectors was twice as large as that of the stagnant sectors (40% versus 20%). However, between 2005 and 2015, the employment share of the dynamic sectors declined to 32%, whereas the stagnant sectors’ employment share rose to 33%. In terms of output, the stagnant sectors’ output also increased faster. The ratio of the dynamic sectors’ output to the stagnant sectors’ output decreased from 312% in 1950 to 245% in 2015. Storm (2017) also argued that the ultimate cause of secular stagnation (i.e., a long-term economic slowdown) in the United States was inadequate demand resulting from a growing dualism between the dynamic and stagnant sectors.

C. Dynamic and (Nonagricultural) Stagnant Sectors in Thailand

In this section, we want to shed new light on the study of the Thai economy by examining dualism based on the concept of dynamic–stagnant sectors from Storm (2017), Temin (2018), and Taylor and Ömer (2019).

To distinguish between the dynamic and stagnant sectors, we use the average labor productivity level, defined as real output over employment. Table 3 shows the average growth and the average level of labor productivity between 2000 and 2018. We use the average labor productivity level (the last column) to categorize the dynamic and (nonagricultural) stagnant sectors. The dynamic sectors, or the high-productivity sectors, include mining, manufacturing, utilities, transport services, business services, financial services, and real estate. The (nonagricultural) stagnant sectors, or the low-productivity sectors, include construction, trade services, government services, and other services. We exclude agriculture here because the sector has shed labor since the 1960s and the decrease in its employment share is still ongoing. Also, as agriculture has been ranked the lowest in terms of productivity and wages, we want to see which sectors laborers move to from agriculture.

| Average Annual Productivity Growth (%) | Average Productivity Level between 2000 and 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | 1990–2000 | 2001–2007 | 2010–2018 | (B ‘000) |

| Agriculture | 5.68 | 2.55 | 3.98 | 88.48 |

| Mining | 12.35 | 1.69 | −6.05 | 6,126.03 |

| Manufacturing | 1.94 | 4.75 | −0.10 | 558.63 |

| Utilities | 8.91 | 1.34 | 2.45 | 1,735.71 |

| Construction | −3.93 | −0.49 | 4.48 | 145.44 |

| Trade services | −1.76 | 0.10 | 4.77 | 258.05 |

| Transport services | 3.25 | 3.64 | 3.36 | 562.73 |

| Business services | 3.42 | 6.18 | −0.70 | 777.04 |

| Financial services | −2.05 | 3.83 | 4.43 | 1,730.02 |

| Real estate | 6.09 | 0.96 | −2.73 | 2,386.73 |

| Government services | 1.34 | 0.04 | 2.09 | 470.13 |

| Other services | −2.72 | 0.30 | 2.84 | 225.22 |

| Total | 3.30 | 3.10 | 3.39 | 313.45 |

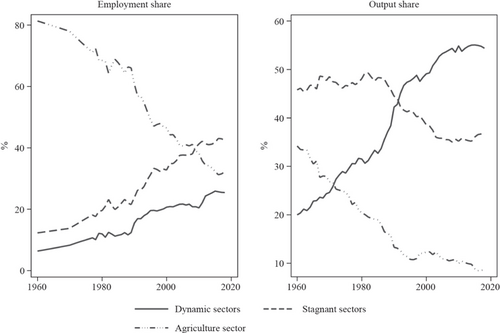

Figure 5 plots employment and output shares for the agriculture, dynamic, and stagnant sectors. The dynamic and stagnant sectors’ employment shares began at 6.4% and 12.3%, respectively, in 1960 and increased toward the end of the 20th century. However, since the 2000s, we can see the polarization between the two as the stagnant sectors grew faster than the dynamic sectors. Although the dynamic sectors’ employment share grew from 20.7% in 2000 to 25.4% in 2018, the stagnant sectors’ employment share increased more rapidly from 32.8% in 2000 to 42.4% in 2018. The stagnant sectors’ employment share also surpassed agricultural employment in 2009 to become the most significant job creator among the three. However, output shares do not exhibit the same pattern. The dynamic sectors’ output share increased from 20.0% in 1960 to 54.4% in 2018. The stagnant sectors accounted for relatively high shares of 45.8% in 1960 and 44.5% in 1990 before falling to a low of 35.2% in 2014. In sum, the most vital job creation, in the stagnant sectors, has not been the strongest value creator for the Thai economy, as the stagnant sectors’ output share has been declining since the 1990s. The dynamic sectors, on the other hand, dominated by 2018 in terms of output share but not in terms of job creation.

Figure 5. Employment and Output Shares of the Dynamic, Stagnant, and Agriculture Sectors, 1960–2018

Notes: The dynamic sectors include manufacturing, information, finance, real estate, and business services. The stagnant sectors include utilities, education, health, private social services, and other services.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Groningen Growth and Development Center’s UNU-WIDER Economic Transformation Database (Kruse et al. 2022).

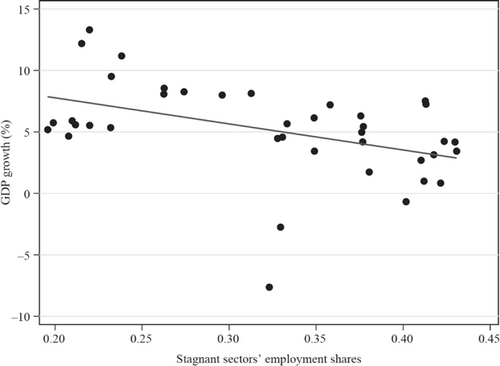

The growing importance of the stagnant sectors has two main implications for the Thai economy: one on economic growth and another on income inequality. First, on the negative side, this growth implies that the Thai economy has, at best, experienced a slowdown in industrialization or, at worst, premature deindustrialization, with either of the two resulting in lower economic growth. Even though labor is still relocating from traditional activities such as agriculture, the dynamic sectors have been too slow to absorb those laborers. Most of them have ended up with jobs in the stagnant sectors. Figure 6 confirms this negative effect of the rise of the employment share of the stagnant sectors. The scatterplot shows the negative relationship between the employment share of stagnant sectors and economic growth between 1980 and 2018, which implies that the higher the share of the stagnant sectors’ employment, the lower the economic growth rate.

Figure 6. Scatterplot of Gross Domestic Product Growth and Stagnant Sector Employment Share, 1980–2018

Notes: The trend line equation is gross domestic product (GDP) growth=12.02 – 21.23 × (stagnant sectors’ employment share). Adjusted R-squared=0.1736. The stagnant sectors include utilities, education, health, private social services, and other services.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Groningen Growth and Development Center’s UNU-WIDER Economic Transformation Database (Kruse et al. 2022).

Second, on the positive side, the shift in jobs toward (nonagriculture) stagnant sectors can decrease income inequality. Agriculture is the least productive sector, and labor in this sector also has the lowest income. Job relocation from the agriculture to stagnant sectors would surely lift the income of laborers closer to the national average, which also confirms what we saw in Figure 3, where the bottom half of incomes increased faster than the top half. Despite slowing aggregate economic growth, the dualism in the dynamic–stagnant sectors has caused income equality to decline by bringing up the bottom 50%.

In sum, in the United States, the dualism between the dynamic and stagnant sectors can explain secular stagnation, or the decreasing trend of economic growth, during the past 4 decades. In Thailand, the dualism between the dynamic and (nonagricultural) stagnant sectors since the 2000s simultaneously impacted the Thai economy positively and negatively; it reduced economic growth and closed the income gap between rich and poor.

IV. Dualism between the Formal and Informal Economy

An informal economy is often associated with low labor productivity, poor access to training, significant risks and health concerns, high income insecurity, and a lack of worker protection (International Labour Organization 2021).5 An informal sector, or a shadow economy, has been part of the Thai economy since the dawn of industrialization. As the process of economic development intensified in the 1980s, more rural people moved to Thai urban areas to find jobs in the manufacturing sector. The informal urban sector began to absorb urban unemployment since job opportunities in the formal sector were insufficient to absorb the huge influx of labor.

An informal sector plays a positive role in an urban area when an economy falls into a recession. After the AFC, many Thai laborers moved from the formal to the informal sector rather than remain unemployed. Rural agriculture could not absorb the shock since the structure of the Thai economy had drastically changed by 1997 compared to the past (Warunsiri 2011). Agriculture activities declined substantially and could not provide jobs for those workers anymore. As a result, it was informal employment in urban areas that absorbed workers after the AFC (Sauwalak and Chetta 2000).

A. Informal Sector in Thailand

According to the 2021 Informal Employment Report, the National Statistical Office of Thailand (NSO) began conducting informal employment surveys annually since 2005. The survey data help with the implementation of a policy designed to extend social security coverage for all occupations regardless of employment status (NSO 2021). The NSO defined a person as being employed if he or she is at least 15 years old and for at least 1 hour that week “worked for wages/salary, profits, dividends, or any other kind of payment, including those who worked without pay in business enterprises or on farms owned or operated by household heads or members” (NSO 2021, p. 27). Formal employment comprises employed persons who are protected or receive social security benefits from work. Examples include government office jobs, employees protected by labor laws, and employed persons insured by the Social Security Office. Informal employment, therefore, “refers to employed persons who are not protected or have no social security from work like formal employment” (NSO 2021, p. 27).

The informal sector in Thailand has been relatively large for a long time, even compared to other countries in Southeast Asia. Hewison and Tularak (2013) showed that from 1980 to 2000, informal employment in Thailand declined from almost 80% to less than 60%. However, it then increased in the 2000s and stayed at more than 60%. Ohnsorge and Yu (2022) compared informal employment (as a percentage of informal workers in total employment) and informal output (as a percentage of output in GDP produced by informal firms). Informal employment in East Asia and the Pacific has been above average compared to other emerging and developing economies, whereas informal output has been moderate. Surprisingly, informal output in Thailand was the highest in East Asia and the Pacific during 2010–2018 at more than 40% of GDP, exceeding that of Indonesia, Malaysia, the People’s Republic of China, and Viet Nam. For informal employment, Thailand ranked fourth behind the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, and Viet Nam. In all countries except Malaysia, the share of informal employment was greater than informal output during the review period.

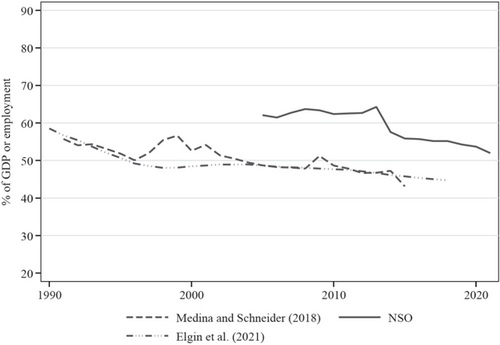

Medina and Schneider (2018) estimated the size of the shadow economy for 158 economies worldwide between 1991 and 2015.6 Whereas the average size of the shadow economy around the world was 31.9% of official GDP, the average size of the shadow economy in Thailand was 50.6%, which was higher than in Cambodia (46.0%); India (23.9%); Indonesia (24.1%); Malaysia (31.5%); the People’s Republic of China (14.7%); the Philippines (39.3%); the Republic of Korea (25.7%); Taipei,China (32.5%); and Viet Nam (18.7%). Elgin et al. (2021) created a database that indirectly estimated the informal output based on the dynamic general equilibrium for 196 economies from 1990 to 2018. Using this method, Thailand’s average size of informal output during 1990–2018 was 49.0%, which is close to what Medina and Schneider (2018) found, confirming that the size of the informal sector in Thailand has been especially large compared to other East and Southeast Asian economies.

Figure 7 compares the shadow economy sizes from Medina and Schneider (2018), informal output from Elgin et al. (2021), and the informal employment share from the NSO. The two estimated series, from Medina and Schneider (2018) and Elgin et al. (2021), are very close to each other. All three series show a declining trend in the last years of the review period. Medina and Schneider (2018) found a declining trend after 2000; for Elgin et al. (2021), it began to decline around 2009; and the trend from the NSO declined from 2014. Overall, the size of the shadow economy or informal sector in Thailand was still large at the end of our review period, even though it decreased in the last few years before 2018. We interpret this decline of the informal economy as a progressive structural transformation since laborers move from traditional sectors, such as agriculture, to modern sectors in urban areas.

Figure 7. Estimations of Informal Output and Employment

GDP=gross domestic product, NSO=National Statistical Office of Thailand. Notes: Medina and Schneider (2018) and Elgin et al. (2021) estimated the size of the informal economy as a percentage of official GDP. The NSO surveyed informal work as a percentage of total employment. Sources: Medina and Schneider (2018), Elgin et al. (2021), and NSO (2021).

Table 4 shows informal employment by economic sectors according to the NSO for 2005, 2009, 2013, and 2019. For each sector, we have two columns: “% Sector” shows the percentage of informal employment out of total employment by each sector, and “% All Informal” represents the percentage of sectoral informal employment out of total informal employment, which equals 100. For agriculture, informal employment has always accounted for more than 90% of jobs in the sector itself and around 60% of Thailand’s total informal employment. For the trade services sector, informal employment is around 60%, while this sector contributes about 25% of the country’s total informal employment. Even in manufacturing, informal employment has always been more than 20% and never tapered off. Between 2013 and 2019, total informal employment in Thailand decreased from 62% to 54%. Looking closer at this decline, trade services and transport and business services were the leading sectors in terms of reducing their informal shares, which coincides with the transformation of sectoral employment discussed in the previous section. Trade services gained in importance in the past 2 decades and, at the same time, increased its level of formal employment in the past few years, which will have a significant impact on income inequality.

| 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | 2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Sector | % All Informal | % Sector | % All Informal | % Sector | % All Informal | % Sector | % All Informal | |

| Total | 62.08 | 100.00 | 63.37 | 100.00 | 64.28 | 100.00 | 54.27 | 100.00 |

| Agriculture | 91.51 | 62.73 | 92.61 | 60.69 | 94.12 | 61.34 | 91.28 | 56.39 |

| Mining | 3.93 | 0.01 | 20.21 | 0.04 | 14.95 | 0.04 | 18.66 | 0.06 |

| Manufacturing | 21.17 | 5.03 | 25.12 | 5.48 | 27.06 | 5.83 | 20.82 | 5.97 |

| Utilities | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 15.58 | 0.13 | 6.93 | 0.08 |

| Construction | 43.03 | 3.54 | 44.79 | 3.77 | 57.37 | 5.17 | 44.47 | 4.43 |

| Trade services | 68.65 | 23.14 | 68.19 | 23.64 | 65.62 | 20.66 | 57.31 | 24.97 |

| Transport services + Business services | 54.78 | 2.62 | 52.47 | 2.40 | 38.36 | 2.67 | 28.12 | 3.38 |

| Financial services | 5.56 | 0.08 | 3.66 | 0.06 | 8.68 | 0.15 | 5.13 | 0.13 |

| Real estate | 26.67 | 0.77 | 26.98 | 0.82 | 34.94 | 0.19 | 28.10 | 0.26 |

| Government services | 2.36 | 0.30 | 8.98 | 1.20 | 9.42 | 1.27 | 3.95 | 0.65 |

| Other services | 39.94 | 1.79 | 45.10 | 1.92 | 56.44 | 2.54 | 52.71 | 3.69 |

B. Informality and Inequality in Thailand

Inequality and informality can have a bidirectional relationship (Dell’Anno 2021). On the one hand, informal employment provides low-skilled, low-income workers with job opportunities that can reduce income inequality. On the other hand, informality can reduce tax revenues since informal workers and businesses contribute significantly less income tax and result in ineffective redistributive policies and higher inequality (Chong and Gradstein 2007).

Most studies confirm a positive relationship between inequality and informality, although the causality is still inconclusive. Using data from 16 transition economies between 1987–1989 and 1993–1994, Rosser, Rosser, and Ahmed (2000) argued that the levels of informality and inequality within these economies are highly and positively correlated. They supported the idea that causality can run in both directions. On one hand, higher informality implies a low tax base, reducing the policy space to redistribute income. On the other hand, higher inequality may reduce trust in society and lead firms to engage more in the informal sector. The study, however, did not try to identify the causation. Mishra and Ray (2010) used firm-level data and argued that wealth and income inequality determines the size of the informal sector, which is highly correlated with corruption. Corruption and informality are highly linked as corruptible inspectors thrive in the larger informal sector. Elgin et al. (2021) used two datasets covering 86 countries between 1960 and 2016 and found that the rates of profit and informality are positively correlated with income inequality. Elgin and Elveren (2021) examined a panel dataset with 125 countries from 1963 to 2018 and found that informality is negatively associated with inequality in rich countries but positively associated with inequality in poor countries. Additionally, women’s labor force participation is negatively correlated with income equality.

There has long been a wage gap between formal and informal workers in Thailand. Charoenloet (2015) claimed that in 2009 over half of the Thai labor force was engaged in nonwage employment. With a slow pace of technological upgrading, Thailand has experienced higher levels of subcontracting and more informal homeworkers than formal employees. This fragmentation of the labor market also led to a decline in collective bargaining power, which may result in wage inequality between formal and informal workers. Several studies have also examined the penalty for being employed informally compared to formally. In general, informal workers receive less than their cohorts in the formal sector after controlling for other factors. Ohnsorge and Yu (2022) found, from a review of 18 studies, that the formal wage premium—how much more formal workers earn than informal workers—was about 18%.

Two studies investigated wage differentials between formal and informal workers in Thailand. Based on data from the household socioeconomic survey in 2011, Dasgupta, Bhula-or, and Fakthong (2015) applied a quantile regression and found that informal workers had a lower income at all earnings levels, controlling for other factors. They also found that women earned around 24.9% less than men. The gender gap became smaller at higher monthly salaries, while workers in agriculture earned lower incomes compared to workers in the industry and service sectors. Korwatanasakul (2021) utilized the micro-level data from the NSO’s Informal Employment Survey, 2006–2019. Using a quantile regression model, the study confirms the same result. There is a systemic wage gap between formal and informal workers in all quartiles of the wage distribution, with the largest penalty being informal employment at the lowest tail of the wage distribution (20th quartile). On average, informal workers received 33% less than formal workers. Korwatanasakul (2021) also found a gender gap in all wage quartiles, with a higher penalty for women at the higher distributional quartile. On average, female workers earned 13% less than their male cohorts.

Table 5 shows the average salary and the wage ratio between formal and informal workers in 2011 and 2015 based on the NSO’s Informal Employment Survey. The wage ratio is the average monthly salary of informal workers over the average monthly salary of formal workers. If the ratio equals 1, both formal and informal workers receive the same average monthly salary, and the wage gap is nil. Overall, formal workers had a significantly higher income than informal workers. The average wage ratio is 0.43, which implies that an informal worker on average received less than half the formal worker’s salary, or that the informal penalty is more than 50%, the largest result compared with the two studies mentioned above. In 2015, formal agriculture workers received the lowest salary among formal workers (B6,458 per month), and informal agricultural workers received the lowest salary among informal workers (B5,010 per month). Meanwhile, the average monthly salary for accommodation and food service, a branch of trade services, was B10,849 for formal workers and B7,848 for informal workers. Both are much higher than informal salaries in the agriculture sector and closer to the national average (Table 5, first row), which implies that any reallocation of labor out of agriculture to trade services should bring the labor income of the bottom half of earners closer to the average, resulting in less inequality.

| 2011 | 2015 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal | Informal | Wage Ratio | Formal | Informal | Wage Ratio | |

| Total | 11,223 | 4,525 | 0.40 | 14,427 | 6,583 | 0.46 |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 6,408 | 3,730 | 0.58 | 6,458 | 5,010 | 0.78 |

| Mining and quarrying | 13,420 | 6,727 | 0.50 | 21,745 | 9,264 | 0.43 |

| Manufacturing | 8,765 | 4,485 | 0.51 | 12,464 | 6,624 | 0.53 |

| Electricity, gas, and steam supply | 24,163 | 8,000 | 0.33 | 30,306 | 21,095 | 0.70 |

| Water supply | 16,577 | 5,515 | 0.33 | 13,596 | 7,458 | 0.55 |

| Construction | 8,014 | 5,139 | 0.64 | 11,169 | 7,273 | 0.65 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 9,317 | 5,252 | 0.56 | 12,049 | 7,465 | 0.62 |

| Transportation storage | 14,465 | 6,642 | 0.46 | 17,732 | 13,273 | 0.75 |

| Accommodation and food service | 7,494 | 4,442 | 0.59 | 10,849 | 7,848 | 0.72 |

| Information and communication | 26,441 | 5,133 | 0.19 | 24,753 | 10,363 | 0.42 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 23,014 | 8,046 | 0.35 | 23,366 | 13,433 | 0.57 |

| Real estate activities | 13,101 | 19,000 | 1.45 | 15,847 | 7,756 | 0.49 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical | 19,398 | 4,326 | 0.22 | 26,506 | 7,831 | 0.30 |

| Administrative and support services | 8,803 | 6,317 | 0.72 | 12,675 | 7,570 | 0.60 |

| Public administration and defense | 13,598 | 6,386 | 0.47 | 17,082 | 8,174 | 0.48 |

| Education | 20,416 | 5,554 | 0.27 | 24,171 | 8,140 | 0.34 |

| Human health and social work | 14,307 | 5,653 | 0.40 | 18,690 | 5,958 | 0.32 |

| Arts, entertainment | 8,519 | 5,882 | 0.69 | 12,529 | 7,340 | 0.59 |

| Other service activities | 8,014 | 3,662 | 0.46 | 10,752 | 6,653 | 0.62 |

| Activities of household as employers | 5,948 | 3,974 | 0.67 | 8,642 | 5,894 | 0.68 |

| Activities of extraterritorial | 25,128 | 25,128 | 1.00 | 37,741 | 37,741 | 1.00 |

| Unknown | 14,774 | 10,000 | 0.68 | 17,255 | 9,000 | 0.52 |

V. Regression Analysis

We investigate the effects of double dualism on income inequality using econometric regression. The main variables are the inequality index (Gini coefficient), the size of the informal sector, and the employment share of stagnant sectors (% of total employment). We hypothesize that Thailand’s decreasing inequality in the last 3 decades can be explained by a shrinking informal sector and the growing stagnant sectors.

A. Data and Model Specification

Many factors can lead to changes in income inequality. We follow the list of control variables from Baymul and Sen (2019, 2020) and Huynh and Nguyen (2020), which are three studies that focus on what determines income inequality. The descriptive statistics of the main and control variables, including the sources, are shown in Table 6. All data are time series data from 1990 to 2018. The mean of Thailand’s inequality was decreasing during this period. The stagnant sector’s employment share averaged 32.2%, and the GDP growth rate averaged 4.7%.

| Variable | Definition | Original Data Source | Mean | Std. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginigrowth | Growth rate of Thailand’s Gini coefficient | World Inequality Database | −0.286 | 1.491 | −3.463 | 3.472 |

| informalgrowth | Growth rate of Thailand’s informal sector’s share of GDP | Elgin et al. (2021) | −0.950 | 1.134 | −3.077 | 0.832 |

| stagnantempshare | Stagnant sectors’ employment share | GGDC (Kruse et al. 2022) | 0.322 | 0.080 | 0.196 | 0.431 |

| GDPgrowth | Thailand’s GDP growth rate | World Development Indicators | 4.759 | 4.154 | −7.634 | 13.288 |

| Tradepercent | Thailand’s share of exports and imports to GDP | World Development Indicators | 98.798 | 31.068 | 47.384 | 140.437 |

| FDI | Thailand’s net capital inflows | World Development Indicators | 2.169 | 1.505 | −0.970 | 6.435 |

| Inflation | Thailand’s inflation rate | World Development Indicators | 3.537 | 3.663 | −0.900 | 19.704 |

| Humancap | Human capital index | Penn World Table 10.0 (Feenstra, Inklaar, and Timmer 2015) | 2.242 | 0.346 | 1.560 | 2.804 |

| Crisis | Dummy variable for the period before and after the AFC | Authors’ determination | 0.595 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

We tested the dependent variable to determine if it is stationary and transformed the dependent variable to the growth rate of the Gini coefficient. We also tested if the dependent variable follows the autoregressive moving average model using the correlation function and partial correlation function, and found that the autoregressive moving average (1,0,1) is the most appropriate functional form of the model. Equation (1) below shows the model specification for Gini coefficient growth, informal sector output shares, and control variables in Thailand from 1990 to 2018 :

B. Results

Table 7 shows the estimation results of the impact of the informal sector and stagnant sectors on income inequality in Thailand. The informal sector’s output growth coefficient is positive and statistically significant at the 99% confidence level. The share of the informal sector moves in the same direction as the change in inequality. Our finding is consistent with Rosser, Rosser, and Ahmed (2000), who obtained a positive coefficient between the unofficial economy and the Gini coefficient using data from 18 transitional economies in 1994.

| Dependent Variable: Ginigrowth | |

|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Coefficients (Standard Error) |

| informalgrowth | 2.926 (0.404)*** |

| stagnantempshare | −18.416 (10.852)* |

| GDPgrowth | −0.133 (0.051)*** |

| Tradepercent | −0.043 (0.015)*** |

| FDI | 0.148 (0.215) |

| Inflation | 0.335 (0.120)*** |

| Humancap | 10.332 (2.720)*** |

| Crisis | −6.934 (1.429)*** |

| Constant | −6.113 (2.727)** |

| AR(1) | −0.746 (0.094)** |

| MA(1) | 1.000 (0.000)** |

| Log pseudolikelihood | −31.587 |

| Wald Chi-squared | 4.70e+12 |

| Observations | 28 |

For the opposite causality, Winkelried (2005), Chong and Gradstein (2007), and Dell’Anno (2016) are among those who claim that when inequality increases, the shadow economy will also expand. Given the possibility of two-way causality, we ran the Granger Causality test and found that the opposite direction is not statistically significant. The result of the Granger Causality test is explained in Table 8. In the case of Thailand, the causality runs only one way, from informality to inequality, not the other way around.

| Equation | Excluded | Chi-squared | df | Prob>Chi-squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginigrowth | informalgrowth | 9.907 | 2 | 0.007 |

| Ginigrowth | All | 9.907 | 2 | 0.007 |

| informalgrowth | Ginigrowth | 4.582 | 2 | 0.101 |

| informalgrowth | All | 4.582 | 2 | 0.101 |

In terms of the stagnant sectors, when the employment share of the stagnant sectors increases by 1%, the Gini coefficient will decrease by 18%. The negative coefficient of the stagnant sectors’ employment share is expected. Thailand’s agriculture sector’s employment dropped dramatically after industrialization, and stagnant sectors absorbed more surplus labor from the agriculture sector than the dynamic sectors. As a result, the bottom 50% in terms of income, most of whom were previously working in agriculture, experienced an increase in income, which helped reduce income inequality.

The control variables—trade (% of GDP), GDP growth, inflation, human capital, and a dummy variable for the AFC—are statistically significant at the 99% confidence levels. Trade, GDP growth, and the AFC have a negative coefficient. International trade and economic growth bring more income to the bottom 50%, thereby helping to lower income inequality. Inflation has a positive coefficient, which implies that higher inflation will hit lower-income households harder and widen the income gap. We also find a positive coefficient for human capital, implying that better education will increase inequality, thus following the Kuznets curve. The coefficient of the economic crisis dummy is negative and statistically significant, which indicates that the AFC resulted in structural change that mitigated income inequality. Finally, to check for robustness, we replicate the model and vary the dependent variables from Gini coefficient to income shares of the top 1% and 10%. Results are shown in Table 9. The same results hold across three variables, which confirm that our main model is robust.

| Gini Coefficients from the World Inequality Database | Income Share from Top 1% | Income Share from Top 10% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forms of Dependent Variables | Growth Rate (%) | 1st Difference | 1st Difference |

| informalgrowth | (+)*** | (+)*** | (+)*** |

| stagnantempshare | (−)* | (−)*** | (−)** |

| GDPgrowth | (−)*** | (−)* | (−)** |

| Tradepercent | (−)*** | (+) | (−)** |

| FDI | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| Inflation | (+)*** | (−) | (+)*** |

| Humancap | (+)*** | (+)** | (+)*** |

| Crisis | (−)*** | (−)*** | (−)*** |

| Constant | (−)** | (+) | (−)*** |

| AR(1) | (−)** | (−)*** | (−)*** |

| MA(1) | (+)** | (−)*** | (−)*** |

In conclusion, structural changes in the Thai economy have impacted income inequality. Unlike the neoclassical approach, structuralist economics emphasizes that economic structure matters. Sectoral transformation of the economy profoundly impacts income inequality. Recent studies have focused more on institutional or political factors in explaining inequality in Thailand. By adopting the Marxist approach, Hewison (2021) showed how the wealthiest households in Thailand have consolidated wealth after the AFC. Kanchoochat (2023) utilized the institutional approach and showed that the failure of structural and regulatory transformations increased the gap between workers inside and outside agriculture. Jenmana (2018), Jenmana and Gethin (2019), and Simson and Savage (2020) articulated how democratization, especially after a new constitution in 1997, facilitated a platform that called for redistributive policies and resulted in lower income inequality. Our study, using the structuralist approach, focuses on economic factors in explaining income inequality. We provide an alternative explanation by showing how structural dualism can affect income inequality in Thailand.

VI. Conclusion

The AFC was a watershed moment for the Thai economy. Prior to the AFC, Thailand had experienced unprecedented economic growth thanks to rapid industrialization. Economic activities transitioned from agriculture to industry and modern services. Laborers relocated from rural areas to cities, especially Bangkok. In the meantime, income inequality rose to one of the highest levels in Southeast Asia. The roaring “fifth tiger” impressively thrived until July 1997, when the AFC first erupted and marked the end of the Thai economic growth miracle. Since the 2000s, economic growth rates have generally been lower than before the crisis. However, income inequality started to come down with the rise in the share of income of the bottom 50%. In this paper, we apply the structuralist approach to show how changing economic structure has determined the dynamics of income inequality and economic growth in Thailand. In other words, the slowdown of economic growth and declining income inequality since the 2000s have been fundamentally connected. We argue that the recent trend of inequality in Thailand might not be only because Thai society has become more egalitarian but also because the economy has experienced two types of dualism: formal–informal dualism and dynamic–stagnant dualism.

As the Gini index shows that the decreasing trend of income inequality since the 2000s can be attributed to the rising income share of the bottom 50%, we apply the concept of dualism to show why the bottom 50%’s share of income may have risen faster than the top 50%’s share. The first dualism is between the dynamic and stagnant sectors. We use sectoral average labor productivity between 2000 and 2018 as a benchmark to separate the dynamic, or high-productivity, sectors and the (nonagricultural) stagnant, or low-productivity, sectors. In developing countries like Thailand, agriculture still sheds employment, so we exclude it from the dynamic–stagnant categorization. The dynamic sectors are mining, manufacturing, utilities, transport services, business services, financial services, and real estate; the stagnant sectors are construction, trade services, government services, and other services. Based on the employment share, the stagnant sectors have grown faster than the dynamic sectors since the 2000s. The stagnant sectors’ employment share was 42.4% in 2018, which was larger than agriculture’s employment share at 32.2%. However, based on the output share, the stagnant sectors’ share constantly declined during the 1990s to merely 35.2% in 2014. In contrast, the dynamic sectors’ output share was still rising and sat at 55.1% in 2015. In sum, structural change in Thailand since the 2000s has been regressive, shifting output from the dynamic sectors to the stagnant sectors. The rise of the stagnant sectors has two main implications. First, it caused a growth slowdown, or what economists label the middle-income trap. Second, it decreased income inequality because laborers who relocated from agriculture received higher incomes than before, but not as high as with moving toward the dynamic sectors. As a result, the rise of stagnant sectors’ employment propelled the rise of the bottom 50%’s share of income as the labor force emigrated from agriculture.

The second dualism is between the formal and informal sectors. The informal sector in Thailand is huge compared to other East and Southeast Asian economies. According to the NSO, informal employment reached more than 60% in 2013 before declining. Even today, informal employment still comprises more than half of the total labor market. More than 60% of informal laborers work in agriculture, followed by trade services at less than 25%. In Thailand, informal employment positively correlates with income inequality because there has been a significant wage gap between formal and informal workers. In 2011 and 2015, the overall wage ratio was less than 0.5, implying that informal workers received less than half of formal workers’ income. It indicates that as the informal sector has scaled down in the past few years, due to progressive structural transformation, more workers filled jobs in the formal sector, which is expected to reduce overall income inequality.

Finally, we provide an econometrical analysis of the double dualism in Thailand using regressions. We find that the size of the informal sector positively correlates with the variation in the Gini coefficient. As Thailand’s informal sector has been decreasing in size since 2014, labor seems to have relocated from the informal to the formal sector. This relocation should reduce the income gap, boost the income of the bottom half, and reduce inequality since most informal workers (more than 80%) work in agriculture and trade services. In terms of the employment share of the stagnant sectors, we find that the share negatively correlates with income inequality. As the stagnant sectors’ employment size increases, income inequality declines. These results confirm our hypothesis that the slowdown in economic growth and declining income inequality in Thailand can be explained by double dualism. The rise of stagnant sectors has retarded Thai economic growth, although it has helped decrease income inequality. Informality in Thailand positively correlates with a high level of income inequality. Thus, a decline in the informal sector helps reduce inequality in Thailand.

ORCID

Tanadej Vechsuruck  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0625-1233

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0625-1233

Praopan Pratoomchat  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6523-4551

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6523-4551

Notes

1 This group includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Thailand, Uruguay, and Venezuela (Simson and Savage 2020, Appendix 1).

2 World Inequality Lab. World Inequality Database. https://wid.world/ (accessed 24 July 2022).

3 Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) of Thailand. Poverty and Income Inequality Statistics. https://www.nesdc.go.th/main.php?filename=PageSocial (accessed 24 July 2022).

4 World Bank. World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed 24 July 2022).

5 Likewise, informal firms often fall outside of legal regulations and labor laws and are involved in tax evasion and corruption.

6 For Medina and Schneider (2018), the shadow economy is another name for the informal economy. A shadow economy includes legal economic and productive activities, not illegal or criminal activities. The shadow economic activities are hidden from the authorities for monetary, regulatory, or institutional reasons.