Enhancing Food Security in an Era of Rising Fertilizer Prices: Evaluation of an Intervention Promoting Mungbean Adoption in Nepal

Abstract

The improved food security in Asia that has facilitated the region’s development progress depends on nitrogenous fertilizers. Rising prices and shortages of imported fertilizer have prompted countries to explore alternative sources of crop nitrogen, including diversification with legumes. We evaluate an intervention in Nepal that promoted mungbean adoption. Our doubly robust impact evaluation approach accounts for nonrandom patterns of adoption related to livestock rearing, participation in agricultural cooperatives and training, and greater irrigated land use. Adopters growing mungbean for the 2-year study period showed an average increase of 20 kilograms (kg) in their annual consumption of mungbean-based foods, applied almost 40kg per hectare (ha) less fertilizers to their rice crops, and obtained an additional 280kg in rice yield per ha. Hence, agricultural innovations that use legumes such as mungbean can help promote sustainable intensification of cereal-based production systems, while enhancing food security and reducing balance-of-payments issues for the countries dependent on fertilizer imports.

This study was conducted within the framework of the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer project and Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia project, which is funded by the United States Agency for International Development. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. We greatly appreciate the editor for his constructive comments, suggestions, and careful handling of the paper. The Asian Development Bank recognizes “Timor Leste” as Timor-Leste.

I. Introduction

The improved food security in Asia that has facilitated the region’s development progress, even as populations grew rapidly, depends on nitrogenous fertilizers (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations2016, Pandit et al.2022).1 Yet, despite the importance of nitrogenous fertilizers to food security in Asia, the timely availability and affordability of fertilizers for many smallholder farmers are highly questionable (Gautam, Choudhary, and Rahut2022; Gautam et al.2022). These issues are especially salient in the current era of rising fertilizer prices and increasing fertilizer shortages. For example, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 dramatically increased the price of nitrogenous chemical fertilizers by at least 30% from a year earlier (Hebebrand and Laborde2022). Low-income countries from Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa that solely rely on imported fertilizers, while also providing fertilizer subsidies to domestic farmers, faced budgetary constraints in procuring the required amounts, leading to a critical shortage of nitrogenous fertilizers (Behnassi and El Haiba2022, Hebebrand and Glauber2023).

In the longer term, there are also issues of excessive use of nitrogenous fertilizer threatening air and soil quality, and endangering climate stability, ecosystems, and human health (Singh, Tiwari, and Abrol2023). As a result of both budgetary pressure and environmental issues, countries such as Sri Lanka have implemented policy measures to disincentivize the use of nitrogenous fertilizers and encourage farmers to use biological sources of nitrogen (Moring et al.2023). To the extent that a shortage of fertilizer affects the yields of major food crops, higher food prices and reduced food consumption for poor sections of society are likely. If the malnourished segment of the population increases, countries will be unable to meet the Sustainable Development Goal targets pertaining to nutrition and food security. Consequently, several countries relying on imports of chemical fertilizers are developing strategies to reduce their dependence by adopting more sustainable food production (Adhikari, Shrestha, and Paudel2021; Hebebrand and Laborde2022; United States Department of Agriculture2022; Moring et al.2023).

Recent research on cereal-based cropping systems has promoted crop diversification and the inclusion of legumes such as nitrogen-fixing mungbean (Ali et al.1997; HanumanthaRao, Nair, and Nayyar2016; Nair and Schreinemachers2020; Sequeros et al.2020; Depenbusch et al.2021; Mmbando et al.2021). Mungbean is a popular pulse among urban consumers in Nepal, and demand for it is met mainly through imports from India: Nepal imported about 32,000 tons of mungbean grain in 2021, worth $40 million.2

Modern mungbean varieties could be grown as a cash crop on substantial areas that are fallowed part of the year in South Asia’s cereal-based cropping systems (Timsina and Connor2001; Khanal et al.2004; Rani, Schreinemachers, and Kuziyev2018). Its potential soil health benefits (Chadha2010) and role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions (De Antoni Migliorati et al.2015) can be enhanced by incorporating mungbean biomass as a green manure, whether after pod picking or harvesting. When grown in the spring fallows, mungbean helps sequester carbon and significantly reduces nitrous oxide emissions (Pandey, Shree Sah, and Becker2008). Growing mungbean could allow farmers to reduce their use of nitrogen fertilizers, especially urea and diammonium phosphate (DAP), and therefore sustain staple crop productivity while reducing the greenhouse gas emissions and improving household nutrition through increased consumption of mungbean as a source of protein (Chadha2010, Ebert2014, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations2016). Mungbean is nutrient rich and can benefit children and older people through its high levels of digestible globulin (Nair et al.2013).3 Mungbean crops also interrupt disease cycles in cereal-based cropping systems and act as a pest-trap crop, thereby reducing the need for pesticide use.

A project led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Kathmandu promotes the adoption of nutritious and stress-tolerant mungbean varieties in rice–wheat farming systems in Nepal’s western Terai, a lowland region where rice–wheat rotations predominate.4 An estimated 0.4 million out of 0.7 million total hectares (ha) of Terai farmland are left fallow for 65–75 days after wheat harvest and before rice transplanting (Joshi et al.2014).

From 2015 to 2017, the Center selected four Terai districts—Banke, Bardiya, Kailali, and Kanchanpur—for mungbean promotion and market mapping, varietal testing, engagement with seed companies and millers, and farmer capacity building (Table 1).

| Year | Objective | Intervention | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Identify actors and value proposition | Market mapping workshop (Albu and Griffith2005) with seed companies, millers, farmers, and researchers | Engagement of value chain actors and gap identification in the value chain. |

| 2016 | Catalyze innovation in production and use | Minikit distribution | Distribution through millers of 1-kg seed packets, along with technology tips, of NGRLP pipeline mungbean variety SML 668 to 350 farmers; training conducted for farmers on management practices and awareness created about the multiple benefits of mungbean. |

| 2017 | Develop awareness of market requirements and opportunities | Market facilitation visit | Facilitated a program where mungbean farmers were taken to Poshan Food Ltd. and Duggar Pvt. Ltd. to generate awareness about the required quality parameters of mungbean grains such as moisture, grain size, uniformity, and cleanliness as demanded by buyers, and their consequences on price; contract signing between Poshan Foods Ltd. and the farmer groups and cooperatives. |

| 2019 | Document key lessons | Survey | Conducted survey to assess the drivers of mungbean cultivation and estimate its impact on household welfare. |

This is the first study in Nepal or elsewhere that rigorously assesses the determinants of mungbean adoption and its impact on fertilizer use, agricultural productivity, and food security. Prior studies on mungbean are based mainly on either on-farm (Joshi et al.2014) or on-station trials (Weinberger2005, Devkota et al.2006), or laboratory tests (Vijayalakshmi et al.2003). Schreinemachers et al. (2019) measured the adoption rate of improved mungbean varieties with little attention to assessing the determinants of adoption or estimating its impact. Joshi et al. (2014) qualitatively discussed the benefits and impacts of mungbean adoption in Nepal. Sequeros et al. (2020) estimated the returns on investment from mungbean research and development based on secondary data. Similarly, Depenbusch et al. (2021) assessed the impacts of mechanized mungbean harvesting on gender roles.

In this study, we attempt to answer the following questions: What types of farmers are likely to adopt mungbean? To what extent does mungbean adoption in the spring season reduce urea and DAP use in rice cultivation in the rainy season? What has been the impact of mungbean cultivation on rice yields? And finally, what has been the impact of mungbean cultivation on household consumption of mungbean?

We discuss the challenges, prospects, and opportunities for scaling up mungbean farming, based on findings from the focus group discussions and key informant interviews. We have captured the benefit of growing mungbean from a cropping system perspective, as mungbean adopters have been shown to have improved rice yields in the following seasons (Ali et al.1997). We used cross-section data and employed an inverse-probability-weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) approach to account for the endogeneity of the adoption decision.

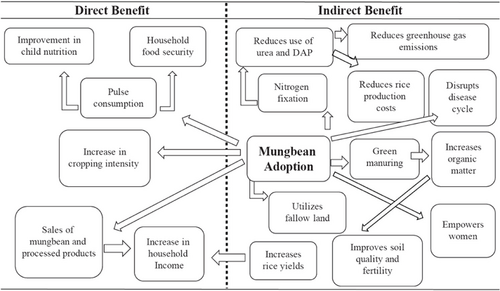

The direct benefits of mungbean adoption for rice–wheat cropping systems include increased food production, household food and nutritional security, and incomes (Khanal et al.2004; HanumanthaRao, Nair, and Nayyar2016). Households with children benefit the most as mungbean is rich in several micronutrient and supplies, mainly protein, thereby reducing child malnutrition (Vijayalakshmi et al.2003, Weinberger2005). The surplus production is usually sold in the market or as processed mungbean products to hospitals and the food industry, improving household incomes and livelihoods (Ebert2014).

There are numerous indirect benefits from mungbean adoption. Mungbean is grown in the spring season, when there is high seasonal migration of males to the cities of Nepal and India for employment. Women remaining on the homestead bear the responsibilities of the household head by engaging in input supply, production, and marketing functions—while also having an opportunity to expand their knowledge base (Quisumbing et al.2021). Mungbean cultivation utilizes fallow land, which helps prevents soil erosion (Khanal et al.2004, Joshi et al.2014) and lessens the social stigma felt by Nepali farmers who leave the land fallow (Shrestha and Pokhrel 2016).

Furthermore, mungbean fixes atmospheric nitrogen in the soil (Sharma, Prasad, and Singh2000; Shah et al.2003; Devkota et al.2006), allowing farmers to reduce nitrogen fertilizer dosages for crops such as rice. This, in turn, contributes to lower emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide (Liu et al.2016), less leaching of nitrogen into water systems (Lu and Tian2016), and reduced fertilizer costs—all of which help make rice production more profitable. Mungbean as a green manure improves soil quality, adding organic matter and increasing porosity. Mungbean has a long taproot system that facilitates water and nutrient uptake from soil strata not normally accessed by cereals, enhancing the overall efficiency of the use of soil resources. Inserting mungbean between rice and wheat in the crop rotation breaks the disease cycle of pathogens. All these will lead to increased rice production that raises both household food consumption and household income (Shanmugasundaram, Keatinge, and d’Arros Hughes2009; Joshi et al.2014; Rani, Schreinemachers, and Kuziyev2018). Mungbean is expected to improve food security, mainly through the consumption of the pulse and increased rice production and consumption. Since mungbean is a new crop that is yet to be produced at commercial scale, farmers are likely to benefit mainly by its direct consumption, the reduced use of expensive urea, and increased rice yield. Overall, mungbean adoption can lead to the intensification of sustainable agriculture practices with positive environmental and social impacts.

This paper is outlined as follows. Following the introduction, section II discusses the materials and methods. Section III presents the research results, section IV provides a discussion, and finally, section V concludes the paper.

II. Materials and Methods

We designed this study to estimate the direct and indirect impacts of growing mungbean to shed light on how this contributes to sustainable intensification in rice–wheat cropping systems. Steps were undertaken as described below.

A. Data Collection

In January 2016, rice millers distributed mungbean seeds as minikits (a 1-kilogram [kg] seed packet along with crop advisory information) to 350 farmers from Banke, Bardiya, Kailali, and Kanchanpur Districts (Figure 1). In 2019, 157 of these farmers were contacted to request their participation in the follow-up household surveys, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews.

Fig. 1. Conceptual Framework for the Direct and Indirect Benefits of Mungbean Adoption

DAP = diammonium phosphate. Source: Authors’ illustration.

To create a suitable counterfactual group, 162 additional households from communities that had not grown mungbean in the past were surveyed. A carefully designed questionnaire to survey the homesteads’ agro-ecological and socioeconomic characteristics was pretested among 10 farmers from Banke and Kailali, and the survey instrument was refined accordingly. Trained and experienced enumerators applied the questionnaire to the selected mungbean growers and nongrowers across districts, recording the responses using Open Data Kit (Table 2). We also control soil characteristics and geographical characteristics at the household level using household Global Positioning System coordinates.

| Description | Banke | Bardiya | Kailali | Kanchanpur | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of households who received a minikit in 2016 | 75 | 120 | 65 | 90 | 350 |

| Number of receiving households surveyed in 2019 | 28 | 50 | 32 | 47 | 157 |

| Mungbean nongrowing households | 30 | 52 | 35 | 45 | 162 |

| Total households surveyed | 58 | 102 | 67 | 92 | 319 |

Key informant interviews were conducted with three seed company representatives, four millers, and five agricultural scientists to understand the challenges and opportunities for expansion of mungbean production. Eight focus group discussions—four with nongrowers and four with mungbean growers—were conducted. There were 8–10 farmers participating in each focus group discussion, of which an average of 30% were women. The discussion explored farmers’ reasons for growing mungbean and the key benefits and challenges they had experienced. The key informant interviews and focus group discussions helped in contextualizing the findings from the household surveys.

B. Statistical Analysis

Determinants of mungbean adoption. Mungbean seeds distributed to farmers by millers were first sown in Nepal in spring 2016. As evidence of adoption, we asked farmers whether they continued to grow mungbean in 2017, 2018, and 2019. We treated their response as a categorical variable—that is, the farmer growing mungbean in all 3 years was considered an adopter. A logistic regression model was used to assess the factors influencing adoption.

The decision to adopt mungbean can be modeled in a random utility framework, where P∗ denotes the difference between the utility from adoption (UiA) and the utility from nonadoption (UiN), such that a farmer i will choose to adopt if P∗>UiA−UiN>0. However, these utilities are not observed. Nevertheless, the utility differences can be expressed as a function of observable components in the latent variable model below :

Assessing mungbean adoption effects. We estimated the effects of mungbean adoption on the amounts of (i) urea and DAP fertilizers applied to the rice crop, (ii) rice yields, and (iii) household mungbean consumption. The survey was conducted in May 2019, which was prior to rice transplanting. Therefore, we were not able to assess the impact of mungbean adoption on the outcomes of interest such as rice yield for that year. Without a doubt, a farmer’s decision is likely to be endogenous. First, the mungbean adopters are not randomly selected. Second, the adoption decision is likely to be based on factors such as soil characteristics, farming experience, a farmer’s social network, and geographical characteristics. Endogeneity issues can be addressed using two-stage least squares, endogenous switching regression, or matching approaches. However, two-stage least squares and endogenous switching regression require strong and valid statistical instruments.5 So our best alternative approach was statistical matching, where adopters are matched to nonadopters, who are expected to be identical based on the “matching variables.” However, the approach requires the inclusion of as many matching variables as possible so that no unobserved variables that influence adoption are left.

We estimated the impact of adoption on outcomes of interest using the doubly robust IPWRA approach, which is also known as “Wooldridge’s double robust.” This approach has been used to estimate the treatment effects under a variety of conditions, including studies of the agriculture sector in Nepal (Wooldridge2007, Imbens and Wooldridge2009, Takeshima2017, Kumar et al.2020).

We have yih representing the vector of outcome of interest, tih the treatment variable indicating the adoption of mungbean, xih a vector of covariates that affect the outcomes, and wih a vector of independent variables that affect the adoption decision. The potential outcome model specifies that the observed outcome variable Y is y0 when t=0 (nonadoption), and Y is y1 when t=1 (adoption). The potential outcome equation model is

The functional forms for y0 and y1 are

The coefficients to be estimated are β0 and β1, and ϵ0 and ϵ1 are the error terms. The households decide to adopt mungbean if

The IPWRA estimators use probability weights to estimate the outcome-regression coefficients, where the weights are estimated inverse probabilities of the treatment. Using these weighted regression coefficients, the average of treatment-level predicted outcomes is computed; the contrast of the average outcome gives the ATE. We estimated the ATE as well as the average treatment effect for the treated (ATT) that shows the sample average effects for the subsample of adopters.

The IPWRA is considered a better approach than propensity score models, as it allows for the treatment and outcome models to account for misspecification, given its double-robust property, therefore ensuring consistent results. The treatment model was estimated using a probit model, while the outcome model was estimated using the linear regression model. We assessed the basic assumptions required for the matching approach, such as the conditional-independence assumption and the overlapping assumption. We retained observations with the probabilities of mungbean adoption between ˆp=0.001 and ˆp=0.999 to ensure the overlapping observation. As mungbean growers and nongrowers are randomly sampled, to a certain extent, we supposed that the third assumption of the independent and identical distribution of the sampled households was likely to be met. However, our results should not be taken as causal effects, but rather correlations with strong controls.

Our approach is based on the selection of observables. However, one of the drawbacks of the propensity score matching is that the ATT may be biased if unobserved heterogeneity (hidden bias) exists between mungbean adopter and nonadopter households. To assess the extent of bias, we calculated the Rosenbaum bounds for ATT estimates in the presence of unobserved heterogeneity (hidden bias) between treated and control households (Rosenbaum2005). At the given level of hidden bias (gamma), the Rosenbaum approach gives the upper- and lower-bound ATT estimates. If ATT estimates do not include 0 in the range of upper and lower bounds, then they are unlikely to be affected by hidden bias.

The covariates in the adoption models were based on the findings from past studies on technology adoption. Household characteristics such as ethnicity; household size; and age, education level, and farming experience of the household head were the key determinants of technology adoption (Marenya and Barrett2007; Foster and Rosenzweig2010; Noltze, Schwarze, and Qaim2013; Teklewold, Kassie, and Shiferaw2013; Kumar et al.2020; Aryal et al.2021). The types of economic and social capital likely to significantly influence technology adoption include farm size, household productive assets, livestock assets, and off-farm income sources. Social capital such as membership in farmer cooperatives or organizations can influence technology adoption (Kumar et al.2020, Aryal et al.2021). Farm characteristics such as the availability of inputs and plot soil quality are significant determinants of technology adoption (Mason and Smale2013; Ghimire, Huang, and Shrestha2015).

Farmers’ participations in agriculture-related training and interactions with extension services, such as participation in demonstrations, also influence technology adoption (Polson and Spencer1991; Ransom, Paudyal, and Adhikari2003; Asfaw et al.2012; Mariano, Villano, and Fleming2012; Ghimire, Huang, and Shrestha2015; Kumar et al.2020). Finally, important determinants of adoption include agro-ecological characteristics of the household’s location and institutional factors (Mason and Smale2013; Ghimire, Huang, and Shrestha2015).

III. Results

A. Covariates and Descriptive Statistics

We present the means and standard deviations for the full sample and for mungbean growers and nongrowers, with observed differences between adopters and nonadopters (Table 3). Among the 124 mungbean adopters in 2017, 116 farmers grew mungbean in 2018 and 98 farmers grew the crop in 2019, reflecting a nonadoption rate of less than 20%. As expected, mungbean growers applied less nitrogen fertilizers to their rice crops than mungbean nongrowers. Despite this, mungbean growers’ rice yields were slightly higher (albeit not statistically significant) than those of nongrowers. Mungbean growers also consumed significantly more (an average of 23.3kg per household) mungbean.

| Adoption of Mungbean (Yes) | Adoption of Mungbean (No) | Total Sample | Mean Difference (Number) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Adopted mungbean in 2017, 2018, and 2019 (yes=1) | — | — | 0.21 | — |

| — | — | (0.41) | — | |

| Adopted mungbean in 2017 and 2018 (yes=1) | — | — | 0.29 | — |

| — | — | (0.46) | — | |

| Urea applied for rice production (kg/katha) | 3.11 | 4.99 | 4.60 | −1.887* |

| (1.39) | (9.19) | (8.22) | (1.136) | |

| DAP applied for rice production (kg/katha) | 2.04 | 3.13 | 2.90 | −1.088*** |

| (1.23) | (3.10) | (2.85) | (0.390) | |

| Rice production in rainy season (kg/katha) | 152.55 | 149.42 | 150.08 | 3.136 |

| (46.40) | (38.99) | (40.60) | (5.630) | |

| Annual home consumption of mungbean (kg) | 32.55 | 9.26 | 14.09 | 23.28*** |

| (33.56) | (21.23) | (26.02) | (3.34) | |

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Male head (yes=1) | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.00253 |

| (0.46) | (0.46) | (0.46) | (0.0639) | |

| Education head (years) | 7.06 | 5.80 | 6.06 | 1.263** |

| (4.45) | (4.44) | (4.47) | (0.615) | |

| Age head (years) | 51.73 | 50.43 | 50.70 | 1.295 |

| (9.14) | (11.97) | (11.44) | (1.583) | |

| Household size (number) | 6.91 | 7.06 | 7.03 | −0.146 |

| (2.95) | (3.49) | (3.38) | (0.468) | |

| Child dependency (%) | 9.91 | 14.20 | 13.31 | −4.292** |

| (11.67) | (14.29) | (13.88) | (1.907) | |

| Household labor size (number) | 4.17 | 4.05 | 4.08 | 0.115 |

| (2.36) | (2.22) | (2.25) | (0.311) | |

| Household with Janajati or Aadibasi ethnicity (yes=1) | 0.45 | 0.62 | 0.58 | −0.165** |

| (0.50) | (0.49) | (0.49) | (0.0677) | |

| Household with Brahmin or Chhetri ethnicity (yes=1) | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.191*** |

| (0.50) | (0.46) | (0.47) | (0.0645) | |

| Annual household food production meets family consumption needs (yes=1) | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.0429 |

| (0.36) | (0.40) | (0.39) | (0.0539) | |

| Works on a daily wage basis (yes=1) | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.10 | −0.0505 |

| (0.24) | (0.31) | (0.30) | (0.0416) | |

| Commercial farming experience (years) | 9.79 | 6.67 | 7.32 | 3.113** |

| (12.45) | (9.27) | (10.07) | (1.384) | |

| Share of irrigated land (%) | 22.99 | 18.97 | 19.81 | 4.024*** |

| (6.90) | (9.55) | (9.20) | (1.255) | |

| Land owned (ha) | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.0138 |

| (0.56) | (0.71) | (0.68) | (0.0939) | |

| Household asset indexa | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.0579 |

| (0.42) | (0.34) | (0.36) | (0.0499) | |

| Livestock owned in tropical livestock unitb | 1.82 | 1.36 | 1.46 | 0.454*** |

| (1.12) | (0.99) | (1.03) | (0.141) | |

| Member of an agricultural cooperative (yes=1) | 0.98 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.140*** |

| (0.12) | (0.36) | (0.33) | (0.0453) | |

| Training on mungbean production (yes=1) | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.363*** |

| (0.50) | (0.29) | (0.37) | (0.0475) | |

| Attended mungbean minikit demonstration (yes = 1) | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.133*** |

| (0.40) | (0.24) | (0.29) | (0.0392) | |

| Altitude of household location (m) | 119.78 | 112.16 | 113.74 | 7.615* |

| (35.24) | (31.35) | (32.29) | (4.451) | |

| Organic matter content in soil (%) | 1.86 | 1.94 | 1.92 | −0.0745 |

| (0.48) | (0.41) | (0.42) | (0.0587) | |

| Nitrogen content in soil (kg/ha) | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | −0.00352 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.00236) | |

| Phosphorus content in soil (kg/ha) | 53.59 | 58.73 | 57.66 | −5.135 |

| (30.57) | (22.29) | (24.27) | (3.349) | |

| Potassium content in soil (kg/ha) | 158.71 | 166.86 | 165.17 | −8.154 |

| (48.70) | (47.25) | (47.59) | (6.575) | |

| Zinc content in soil (parts per million) | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.0366 |

| (0.27) | (0.23) | (0.24) | (0.0326) | |

| Boron content in soil (parts per million) | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.78 | −0.151* |

| (0.74) | (0.58) | (0.62) | (0.0857) | |

| Household in Banke district (yes=1) | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.23 | −0.0754 |

| (0.38) | (0.43) | (0.42) | (0.0579) | |

| Household in Bardiya district (yes=1) | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.34 | −0.0422 |

| (0.46) | (0.48) | (0.47) | (0.0655) | |

| Household in Kailali district (yes=1) | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.18 | −0.0693 |

| (0.33) | (0.39) | (0.38) | (0.0527) | |

| Household in Kanchanpur district (yes=1) | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.187*** |

| (0.50) | (0.42) | (0.44) | (0.0600) | |

| Observations | 66 | 252 | 318 | 318 |

Heads of adopting households had significantly more years of education, lower child dependency ratios (share of children aged below 5 years in a family), more commercial farming experience, more likely affiliation with an agricultural cooperative, more training on mungbean farming, a higher livestock index, and a greater likelihood of having attended a demonstration than their peers in nonadopting households.6 Adoption patterns differed significantly by caste—with higher adoption rates among the Brahmin and Chhetri, and lower adoption rates among the Janajati and Aadibasi.7 Households with more irrigated land had significantly more adoption of mungbean.

We enquired about cropping patterns in focus group discussions. About 80% of mungbean adopters grew the crop in a rice–wheat–mungbean rotation, followed by rice–lentil–mungbean (10%), rice–vegetables–mungbean (5%), and rice–potato–mungbean (5%) rotations. Land in rice–wheat–mungbean systems was fallow for about 70–80 days, with a maximum of 100 days for the rice–potato–mungbean and rice–vegetables–mungbean rotations (Table 4).

| Cropping Pattern | Days Fallow | Adopting Farmers’ Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Rice–wheat–mungbean | 70–80 | 80 |

| Rice–lentil–mungbean | 90–95 | 10 |

| Rice–vegetables–mungbean | 95–100 | 5 |

| Rice–potato–mungbean | 90–100 | 5 |

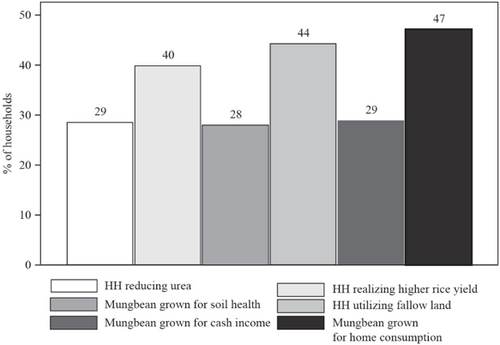

Figure 2 shows the share of households receiving multiple benefits from growing mungbean, with many farmers stating more than one reason for growing the crop. About 29% of the households reduced urea use in rice production after growing mungbean, 28% adopted mungbean for the improvement of soil health, 29% grew mungbean for cash income, 44% grew it for the expected yield increase in their rice crop, and 47% grew mungbean for home consumption.

Fig. 2. Household Reasons for Growing Mungbean

HH=household. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Mungbean Household Survey 2019, funded by the United States Agency for International Development.

B. Factors Influencing Mungbean Adoption

Table 5 presents the estimated results of the logistic regressions and linear probability model on the factors influencing mungbean adoption. Although linear probability uses Cameron and Miller’s (2011) approach in correcting the standard errors, there are no such significant changes in standard errors from estimating the binary logistic regression model with robust standard errors. Therefore, we discussed the results from the binary logistic regression model. Results from marginal effects were presented, as the coefficients can be interpreted in terms of increased or decreased probability of adoption, given the unit change in the independent variables. Only variables that were statistically significant at the 10% level or below were interpreted. The model included district dummies to account for district fixed effects.

| Variable | Logistic Regression (Marginal Effects) | Linear Probability Model |

|---|---|---|

| Male head (yes=1) | 0.041 | 0.049 |

| (0.046) | (0.059) | |

| Education head (years) | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| (0.005) | (0.009) | |

| Age head (years) | 0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Child dependency (%) | −0.003* | −0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Household size (number) | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| (0.006) | (0.009) | |

| Household with migrant (yes=1) | 0.055 | 0.057* |

| (0.038) | (0.034) | |

| Household with Janajati or Aadibasi ethnicity | −0.014 | −0.058 |

| (0.095) | (0.116) | |

| Household with Brahmin or Chhetri ethnicity | 0.003 | −0.002 |

| (0.083) | (0.073) | |

| Works on a daily wage basis (yes=1) | −0.008 | −0.019 |

| (0.025) | (0.036) | |

| Commercial farming experience (years) | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.004) | |

| Share of irrigated land (%) | 0.002*** | 0.002*** |

| (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| Land owned (ha) | −0.026 | −0.036 |

| (0.029) | (0.024) | |

| Livestock owned in tropical livestock unit (ha) | 0.051*** | 0.056*** |

| (0.016) | (0.018) | |

| Household asset index | −0.036 | −0.031 |

| (0.045) | (0.040) | |

| Member of an agricultural cooperative (yes=1) | 0.268*** | 0.202*** |

| (0.077) | (0.005) | |

| Training on mungbean production (yes = 1) | 0.255*** | 0.381*** |

| (0.054) | (0.060) | |

| Attended mungbean minikit demonstration (yes=1) | 0.057 | 0.070 |

| (0.093) | (0.120) | |

| Altitude of household location (m) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Constant | — | −0.239* |

| — | (0.132) | |

| District fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 318 | 318 |

| Pseudo-R-squared | 0.29 | — |

| Log-likelihood | −114.18 | — |

| R-squared | — | 0.29 |

Among the household characteristics, we found only child dependency ratio differences to be statistically significant and that households with higher child dependency ratios are less likely to adopt mungbean. This can be attributed to women providing more time and attention to the care and feeding of children, which can reduce their engagement in agricultural operations.

Households with more irrigated land were more likely to adopt mungbean. On average, a 1% increase in the share of irrigated land increased the probability of adoption by 0.2%. Households with more livestock (e.g., cows, buffalos, goats, and chickens) were also more likely to adopt mungbean. Association with an agricultural cooperative conferred a 27% higher probability of adopting mungbean over nonmember households. Further, on average, a household that had received training on mungbean farming had a 26% higher probability of mungbean adoption, underscoring the value of training activities.

C. Impacts of Mungbean Adoption

We checked the overlap assumption and the balance of the covariates between adopters and nonadopters. The overidentification test of the null hypothesis stating that the covariates are balanced can be accepted with the test statistics of χ2(21)=4.23 with p>χ2=1. We also estimated the normalized differences after weighting each control variable and found them to be smaller than 0.25, which according to Imbens and Wooldridge (2009) suggested that the covariates are well balanced (Table 6).

| Variable | Raw | Weighted |

|---|---|---|

| Male head (yes=1) | 0.056 | −0.080 |

| Education head (years) | 0.407 | 0.031 |

| Age head (years) | 0.008 | −0.119 |

| Child dependency (%) | −0.247 | −0.023 |

| Household size (number) | −0.203 | −0.087 |

| Household with Janajati or Aadibasi ethnicity | −0.270 | 0.024 |

| Household with Brahmin or Chhetri ethnicity | 0.385 | 0.045 |

| Works on a daily wage basis (yes=1) | −0.181 | −0.078 |

| Commercial farming experience (years) | 0.301 | −0.033 |

| Share of irrigated land (%) | 0.389 | 0.183 |

| Land owned (ha) | 0.062 | 0.013 |

| Livestock owned in tropical livestock unit (index) | 0.287 | 0.059 |

| Household asset index | 0.133 | −0.067 |

| Member of an agricultural cooperative (yes=1) | 0.491 | 0.056 |

| Training on mungbean production (yes=1) | 0.861 | −0.044 |

| Attended mungbean minikit demonstration (yes=1) | 0.443 | −0.030 |

| Altitude of household location (m) | 0.037 | 0.031 |

| Banke | −0.068 | −0.067 |

| Bardiya | 0.010 | 0.018 |

| Kailali | −0.125 | 0.108 |

Table 7 summarizes the impact of mungbean adoption. The second column shows the predicted outcome for adopters under nonadoption of mungbean (the counterfactual), the third column shows the impact of mungbean adoption for the whole sample, and the fourth column shows the impact limiting the sample to adopters only—that is, the average differences between predicted outcomes for adopters under adoption and hypothetical nonadoption. We interpreted the results from ATT and showed the results from ATE for just the effects of mungbean adoption at the whole-sample (population) level.

The adoption of mungbean is significantly correlated with higher mungbean consumption (Table 7). The ATT is 19.8, which corresponds to an average consumption increase of about 20kg per year over the hypothetical counterfactual. Given mungbean’s nitrogen-fixing qualities, mungbean adopters reduced the use of urea by an average of 0.86kg per katha (26kg per ha) and the use of DAP by an average of 0.40kg per katha (12kg per ha). Further, when incorporated into the soil postharvest, mungbean residues serve as a green manure, improving the organic matter and soil quality. Results indicate that the mungbean adopters realize an average of 9.40kg per katha (282kg per ha) greater rice production than the hypothetical counterfactual.

| Predicted Outcome Under Nonadoption of Mungbean | ATE | ATT | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mungbean consumption by HH (kg) | 8.39*** | 27.16*** | 19.79*** | 314 |

| (1.14) | (5.34) | (3.99) | ||

| Urea application (kg/katha) | 4.86*** | −1.27 | −0.85* | 310 |

| (0.90) | (0.89) | (0.51) | ||

| DAP application (kg/katha) | 2.98*** | −0.65** | −0.38* | 310 |

| (0.32) | (0.31) | (0.21) | ||

| Rice yield (kg/katha) | 147.74*** | 11.41* | 9.36* | 308 |

| (3.31) | (6.00) | (5.47) |

Table 8 shows the Rosenbaum bound—both the upper and lower bounds of ATT estimates for all outcomes of interest. Except for rice productivity, the upper and lower bounds of ATT estimates do not include 0 at some levels of the hidden bias. Although this bestows some confidence in the ATT estimates, our approach is based on the selection of observables and therefore needs to be cautiously interpreted.

| Mungbean Consumption by HH (kg) | Urea Application (kg/katha) | DAP Application (kg/katha) | Rice Yield (kg/katha) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma | CI+ | C− | CI+ | CI− | CI+ | CI− | CI+ | CI− |

| 1 | 12.5 | 22.5 | −1.68 | −0.56 | −0.73 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 18.33 |

| 1.1 | 12 | 25 | −1.80 | −0.44 | −0.82 | 0.00 | −2.42 | 21.43 |

| 1.2 | 10 | 25 | −1.90 | −0.33 | −0.87 | 0.07 | −4.56 | 23.75 |

| 1.3 | 10 | 25 | −2.02 | −0.22 | −0.93 | 0.12 | −6.86 | 26.67 |

| 1.4 | 10 | 26 | −2.16 | −0.11 | −1.01 | 0.18 | −8.95 | 29.25 |

| 1.5 | 7.5 | 27.5 | −2.26 | 0.00 | −1.07 | 0.24 | −10.70 | 31.67 |

| 1.6 | 7.5 | 27.5 | −2.35 | 0.08 | −1.13 | 0.28 | −12.63 | 33.43 |

| 1.7 | 7 | 28 | −2.43 | 0.15 | −1.18 | 0.33 | −14.43 | 35.25 |

| 1.8 | 5 | 30 | −2.52 | 0.23 | −1.22 | 0.36 | −15.94 | 36.91 |

| 1.9 | 5 | 30 | −2.58 | 0.28 | −1.28 | 0.41 | −17.14 | 38.47 |

| 2 | 5 | 30 | −2.64 | 0.35 | −1.34 | 0.44 | −18.33 | 39.60 |

D. Findings from Key Informant Interviews and Focus Group Discussions

We conducted key informant interviews and focus group discussions to understand farmers’ perceptions of mungbean farming and the associated benefits and constraints. The discussions confirmed the multiple uses and benefits of mungbean such as home consumption, cash income, soil fertility improvement, and fodder for livestock. Most farmers who grew mungbean expected higher rice yields in subsequent seasons. The discussions also revealed that mungbean farming is best suited for smallholder farmers and mainly households headed by women that have limited income opportunities during spring season. Among the nongrowers, we found low levels of awareness regarding mungbean’s soil fertility effects or the health benefits of eating mungbean.

Regarding challenges, farmers cited a lack of irrigation, free grazing of animals, high labor requirements (especially for pod harvesting), unavailability of quality seed, and lack of markets that pay premium prices. Farmers were able to sell mungbean to millers, hotels, hospitals, and neighbors, but they faced marketing challenges owing to the lack of grading facilities for mungbean grain, as well as scattered and low production volumes. Finally, the availability of cheaper mungbean from India reduced the market price for Nepali farmers. Grading and storage facilities were found to be important factors for Nepali farmers to realize premium prices for mungbean.

IV. Discussion

More than 80% of the farmers in our study adopted and grew mungbean during 2017–2019, suggesting the crop meets farmers’ expectations of utility. Although nonadoption may be high in the initial years, adoption is likely to remain stable over time as seed supplies improve and farmers realize the short- and long-term benefits from mungbean adoption. In comparison to other legume crops, mungbean is not widely cultivated in Nepal and usually only on small parcels (Joshi et al.2014).

Regarding the types of farmers more likely to adopt mungbean, our findings suggest that specialized training raises farmers’ awareness about the crop’s value and increases the likelihood of adoption. Farmers affiliated with agricultural cooperatives frequently interact with peers and learn about innovations such as mungbean farming. In the case of farm animals, farmers who do not rear livestock would normally be expected to adopt mungbean for green manuring, but households with livestock proved likely to cultivate mungbean for fodder. In fact, our focus group discussion confirms that the milk yield is higher when livestock are fed mungbean. Farmers with a higher share of irrigated land have a higher probability of adopting mungbean given that, after wheat harvesting, the land is usually dry and mungbean seeds may not germinate and grow without adequate moisture—although the crop has been found to tolerate heat and drought stresses after establishment (HanumanthaRao, Nair, and Nayyar2016).

Our results show that mungbean adoption had a strong positive effect on household mungbean consumption, a direct benefit of mungbean production. In fact, mungbean growing households consumed four times the mungbean grain of nongrowers, while about 57% of the mungbean harvested was used for home consumption in 2018 and 2019. Mungbean has become an important source of green vegetables for farmers, especially in the dry season when green vegetable supplies are scarce in the local markets and 63% of farmers consumed green twigs and immature pods as green vegetables. Past studies have confirmed that mungbean growing households ate more of this crop (Ali et al.1997), increasing their intake of iron, protein, and several other micronutrients, and potentially addressing protein malnutrition (Victora et al.2008). As mungbean is a short-duration crop and offers the potential to improve nutritional security, countries developing climate-smart agriculture and nutrition-sensitive value chains could benefit by introducing mungbean in cereal fallows (Victora et al.2008).

Our findings regarding the significant reduction in the use of urea and DAP for rice are in line with those of Sekhon et al. (2007), who found that mungbean farming in India increased the soil nitrogen status from 33 kg per ha per year to 37 kg per ha per year and saved 25% on nitrogen fertilizers for the next crop—both of which help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and nitrogen runoff into groundwater and aquatic ecosystems (Erisman et al.2013)—in addition to saving farmers’ money. A buildup of residual nutrients in the soil from mungbean, especially nitrogen and organic matter, contributes to higher yields in rotation crops such as rice (Timsina and Connor2001). In the context of rapid fertilizer price increases in international markets and the unavailability of this input in domestic markets (Behnassi and El Haiba2022), mungbean can help ease national fertilizer demands.

Nepal was a net food exporter until 1980 (Adhikari, Shrestha, and Paudel2021), after which national food imports increased dramatically. In the fiscal year 2021/22, Nepal imported various food items worth $286.8 million, resulting in a trade deficit of $13.3 billion.8 Similarly, Nepal’s balance of payments as of August 2023 was a $2.2 billion surplus (Nepal Rastra Bank2023). The country spent $205.8 million in 2021 to import chemical fertilizers. The country also imported mungbean at the cost of $13 million in the same year to meet domestic demand. The study suggests that expanding mungbean production has a huge potential to reduce the import of chemical fertilizers, especially urea, and reduce mungbean imports, thus strengthening foreign reserves and the balance of payments.

Wheat is cultivated on nearly 800,000 ha during the winter in Nepal. It is estimated that about 56% of the wheat fallow (400,000ha) could be utilized for mungbean, resulting in a production of 280,000 tons (based on an estimate of 0.7 tons per ha), which is higher than the current estimated demand of 18,000 tons per year. The surplus production could be exported to earn $238 million annually.9 Additionally, Nepal could save $56.8 million on chemical fertilizers for rice, which is grown as the summer season crop after mungbean.10 Also, with the increased rice yield of 0.28 tons per ha, Nepal would add 112,000 tons ($25.5 million) to its rice harvest.11 In total, mungbean could contribute about $320 million to the balance-of-payments account annually through import substitution, increased production, and increased exports.

In addition to human nutrition and soil health benefits, mungbean also generates income for growers (Ali et al.1997). However, we did not assess this impact, given the difficulties of separating out and controlling complex and multiple household income channels to obtain robust estimates. Nonetheless, mungbean adoption can positively impact household income through the use of fallow land, cost savings from reduced fertilizer for rice, and increased rice yield. On average, farmers cultivated mungbean on 0.3ha. About 90% of the cultivated land remains fallow during the spring season and could be used for expanded mungbean production. The covering of fallow land by mungbean not only improves soil fertility but can also reduce erosion and land degradation (Pandey, Shree Sah, and Becker2008).

This study shows that Nepali households with a limited family labor supply have grown mungbean on a small scale for household consumption and green manuring, which is in line with the findings of Rani, Schreinemachers, and Kuziyev (2018) in Pakistan and Uzbekistan. Joshi et al. (2014) also cited a lack of irrigation and family labor, as well as damage by free-grazing livestock, as challenges for mungbean production in Nepal.

The study accords with agricultural policies in South Asia that support increased crop diversification and a shift away from systems solely comprising rice and wheat production (Birthal, Roy, and Negi2015; Thapa et al.2018; Singh et al.2022). Further, the study contributes to discussions of household nutrition, assessing the effects of mungbean consumption as an inexpensive source of dietary protein and micronutrients (Gillespie et al.2019).

V. Conclusion and Policy Implications

Our findings clearly indicate that mungbean production contributes to cropping system benefits and reduces the chemical fertilizer requirement for rice. This provides a sustainable solution for soil fertility management in the context of chemical fertilizer shortages. Since our data are collected from farmers in areas where mungbean is being promoted, they represent the upper bound of the potential for sustainable intensification of mungbean production in Nepal.

Our findings underscore the importance of mungbean adoption in farming systems in Asia to address the triple challenges of food security, environmental degradation, and climate change. The promotion of mungbean and its expansion offer an attractive pathway for the sustainable intensification of a rice-based cropping system in Nepal and other similar countries in South Asia by minimizing dependency on chemical fertilizers, particularly amid global fertilizer shortages and price hikes. The results also have implications for the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals related to increasing agricultural productivity, maintaining environmental sustainability, and strengthening food security. In many African countries, and particularly in Nepal where about 20% of the agricultural budget is allocated to support fertilizer subsidies, scaling up mungbean farming can reduce fertilizer imports, promote balanced fertilizer application, shrink subsidy budgets, and contribute toward an improved balance of payments.

Training activities on mungbean farming, linked mainly with agricultural cooperatives, can be effective in promoting adoption and the benefits described in this study. Local governments can offer subsidies for pumps or electricity to irrigate mungbean crops. Mechanized harvesters, if available, can reduce labor costs, particularly for harvesting mungbean pods. The introduction of synchronously maturing varieties and development of machine harvesting technology could reduce the workload of women in mungbean farming. As mungbean is still a new crop for most farmers in Western Nepal, there is a need for additional work to strengthen the capacity of seed companies and cooperatives for mungbean seed production, varietal promotion, and marketing. We believe that these findings may be applicable to countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa that import chemical fertilizers and could grow mungbean to meet their domestic requirements.

ORCID

Narayan Prasad Khanal  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6069-234X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6069-234X

Dyutiman Choudhary  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5803-7015

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5803-7015

Ganesh Thapa  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9727-8994

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9727-8994

Notes

1 Fertilizer data were from the Fertilizer Association of India. Statistical Database: All-India Consumption of Fertiliser Nutrients 1950–51 to 2018–19. https://www.faidelhi.org/statistics/statistical-database (accessed 20 January 2023). Population data were from the Asian Development Bank. Total Population, Asia and the Pacific. https://data.adb.org/dashboard/total-population-asia-and-pacific (accessed 20 January 2023).

2 See, for more details, Government of Nepal, Ministry of Industry, Commerce, and Supplies, Trade and Export Promotion Centre. Export and Import Data Bank. http://www.tepc.gov.np (accesed 19 June 2023).

3 As a food, mungbean is rich in protein (240 grams per kilogram [kg]), carbohydrates (630 grams per kg), and iron (6 milligrams per 100 grams)—and it provides other diverse micronutrients beneficial to human health (Weinberger2005).

4 For details on the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center’s mungbean project, see Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (2020).

5 The use of an invalid or weak instrument can yield more biased estimates than simply using the ordinary least squares (Murray1995).

6 The livestock index is estimated as per Chilonda and Otte (2006).

7 The Brahmin and Chhetri castes are considered privileged ethnic groups that are likely to be well educated, relatively rich, and earlier adopters than lower castes such as Janajati, Aadibasi, and Dalit. Therefore, the adoption rate is higher among the higher castes such as Brahmin and Chhetri.

8 See, for more details, Government of Nepal, Ministry of Industry, Commerce, and Supplies, Trade and Export Promotion Centre. Export and Import Data Bank. http://www.tepc.gov.np (accesed 19 June 2023).

9 Total value of mungbean to be exported=Total surplus production (262,000 tons)∗Value of sales per ton ($923).

10 Total savings from chemical fertilizers=Rice area under mungbean production (0.4 million ha)∗Savings from reduced nitrogen fertilizer use (urea and DAP) ∗ Price of nitrogen fertilizers.

11 Estimated based on additional rice (0.28tons/ha) to be produced from 0.4 million ha with a market value of $378.8 per ton.