Efficacy of Oriental Exercises for Non-Motor Symptoms and Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

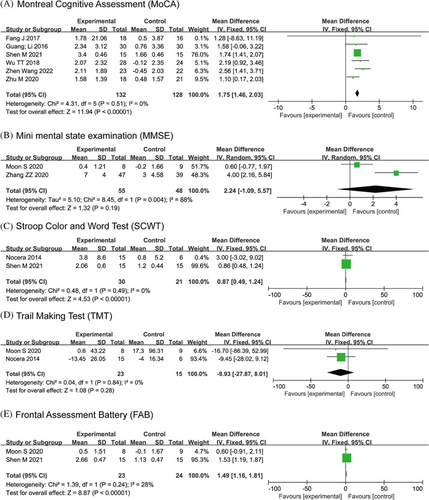

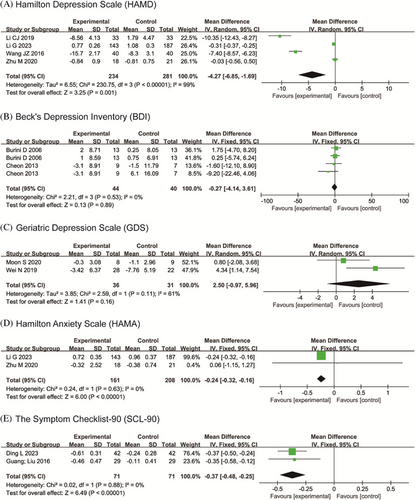

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder without a definitive cure. Oriental exercises (OEs) have emerged as a complementary and alternative therapy for PD, but their efficacy in ameliorating non-motor symptoms (NMS) and quality of life (QOL) remains uncertain. This systematic review and meta-analysis actively investigated the efficacy of OEs in addressing NMS and enhancing QOL and sought to offer recommendations for optimal OE regimens for PD patients. By analyzing 30 controlled trials involving 2029 participants, we found that OEs significantly improved cognitive function, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and QOL compared to control groups. Specifically, significant improvements were observed in several outcome measures: Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ) [MD: −3.67, 95% CI: −5.72–−1.63, P<0.00001, I2=75%], Parkinson’s Disease Non-Motor Symptom Questionnaire (NMSQ) [MD: −2.34, 95% CI: −4.67–−0.01, P=0.05, I2=91%], Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [MD: 1.75, 95% CI: 1.46–2.03, P<0.00001, I2=0%], Stroop Color and Word Test (SCWT) [MD: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.49–1.24, P<0.00001, I2=0%], Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) [MD: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.16–1.81, P<0.00001, I2=28%], Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) [MD: −4.27, 95% CI: −6.85–−1.69, P=0.001, I2=99%], Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) [MD: −0.24, 95% CI: −0.32–−0.16, P<0.00001, I2=0%], and the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) [MD: −0.37, 95% CI: −0.48–−0.25, P<0.00001, I2=0%]. Our findings provide compelling evidence for the potential benefits of OEs in managing NMS and improving QOL in PD patients. To optimize outcomes, we recommend customizing OE regimens based on individual clinical phenotypes, and to validate these results we emphasize the need for rigorous, large-scale studies.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder worldwide. Its diagnosis predominantly hinges on motor symptoms as distinctive clinical presentations (Armstrong and Okun, 2020), as non-motor symptoms (PD-NMS) frequently prove challenging to discern and are sub-optimally addressed in the management of PD (Schaeffer and Berg, 2017). Those afflicted with PD may manifest NMS such as depression, cognitive dysfunction, or sleep disturbances prior to the emergence of motor symptoms, which are commonly disregarded by patients (Chaudhuri et al., 2010). As the disease advances, PD-NMS can result in diminished quality of life (QOL), increased disability, and potentially reduced life expectancy, which affects both patients and their families and exacerbates the overall burden of the disease (Seppi et al., 2019). Presently, there is a lack of established pharmaceutical interventions for PD-NMS (Foltynie et al., 2024). Dopaminergic medications, as the core component of PD treatment, may exacerbate or even trigger certain NMS (Schaeffer and Berg, 2017), necessitating the exploration of complementary and alternative therapies to alleviate PD-NMS and enhance patients’ quality of life (Bhalsing et al., 2018).

Oriental Exercise (OE) is a body–mind exercise that incorporates body stretching and breathing techniques to enhance the flow of Qi and blood in the meridians, aiming for physical and mental harmony (Jin et al., 2019). With advantages such as low risk of adverse effects, ease of practice, and flexibility in terms of location and equipment requirements (Huang et al., 2022), OE is well-suited for long-term rehabilitation targeting a range of chronic illnesses, including but not limited to cardiovascular diseases (Wang et al., 2016b), pulmonary diseases (Shuai et al., 2023), stroke (Chen et al., 2015), and diabetes (Jia et al., 2023). While previous meta-analytical studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of OEs on individuals with PD (Yu et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022), there is a scarcity of research on the impact of OEs on non-motor symptoms (NMS) and quality of life (QOL) in patients with PD. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no meta-analysis that differentiates between the effects of different OE types and exercise dosages on NMS and QOL in PD.

This study aims to systematically evaluate the efficacy of OEs on NMS and QOL in individuals with PD through meta-analysis. We also seeks to explore the impact of various OE types (such as Qigong, Tai Chi, Baduanjin, Wuqinxi, Liuzijue, Daoyin), exercise frequencies (low-dosage ≤ 180min/week, moderate-dosage = 180–240min/week, high-dosage > 240min/week), and durations (short-term ≤ 12 weeks, medium-term = 13–24 weeks, long-term > 24 weeks) to offer insights for the OE regimens of PD patients.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis (CRD42024507834) followed the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 2020 (PRISMA 2020) statement (Page et al., 2021).

Search Strategy

Eight electronic databases were searched, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, CBM, and Wanfang Data. All sources were last searched on January 1, 2024, with language restricted to English and Chinese. The search strategy involved a combination of subject terms and free text, with citation tracking in retrieved papers to ensure comprehensive coverage. The specific search strategy for PubMed is detailed in Table 1.

| No. | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | “Parkinson Disease”[Mesh] |

| 2 | “Parkinson’s Disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “Parkinson’s Disease, Idiopathic”[Title/Abstract] OR “Parkinson’s Disease, Lewy Body”[Title/Abstract] OR “Parkinson Disease, Idiopathic”[Title/Abstract] OR “Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “Lewy Body Parkinson’s Disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “Idiopathic Parkinson Disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “Lewy Body Parkinson Disease”[Title/Abstract] OR “Primary Parkinsonism”[Title/Abstract] OR “Parkinsonism, Primary”[Title/Abstract] OR “Paralysis Agitans”[Title/Abstract] OR “PD”[Title/Abstract] |

| 3 | 1 OR 2 |

| 4 | “Tai Chi”[Mesh] OR“Tai Ji Quan”[Title/Abstract] OR “Shadow Boxing”[Title/Abstract] |

| 5 | “Qigong”[Mesh] OR“Daoyin”[Title/Abstract] OR “Liuzijue”[Title/Abstract] OR “Six Character Judgment”[Title/Abstract] OR “six-healing sounds”[Title/Abstract] OR “Baduanjin”[Title/Abstract] OR “Eight-sectioned Exercise”[Title/Abstract]OR “Wuqinxi”[Title/Abstract] OR “”Five-animal Exercises”[Title/Abstract] OR “Yijinjing”[Title/Abstract] OR “Traditional Chinese Exercise”[Title/Abstract] |

| 6 | 4 OR 5 |

| 7 | “Randomized Controlled Trial”[Mesh] |

| 8 | “Randomized Controlled Trial”[Title/Abstract] OR “Controlled Clinical Trials, Randomized”[Title/Abstract] OR “Clinical Trials, Randomized”[Title/Abstract] OR “Trials, Randomized Clinical”[Title/Abstract] OR “Clinical trial”[Title/Abstract] OR “Clinical trials”[Title/Abstract] |

| 9 | 7 OR 8 |

| 10 | 3 AND 6 AND 9 |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were developed using the PICOS (participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design) approach (see Table 2). Exclusion criteria included: (1) non-clinical controlled trials; (2) subjects with secondary Parkinson’s syndrome and Parkinson’s plus syndrome; (3) literature in a language other than English or Chinese; (4) lack of clear diagnostic criteria or mismatched study outcome indicators; (5) studies with duplicates, insufficient or incomplete data, or significant statistical errors.

| Population | Adult (>18y) Gender with a definite diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Duration of disease are not limited. |

| Intervention | Oriental Exercises, such as Qigong, Daoyin, Tai Chi, Baduanjin, Liuzijue, Wuqinxi, Yijinjing. |

| Comparator | Receive regular exercise or no exercise. |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: PDQ-39, NMSQ. |

| Secondary outcome: Other published rating scales of Parkinson’s non-motor symptoms and quality of life, such as MoCA, HAMD, HAMA, MMSE, PDSS. | |

| Study design | Randomized or non-randomized controlled trials. |

Data Selection and Extraction

Two researchers (PWQ and ZRH) independently screened articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and cross-checked the results. Data extracted from studies meeting inclusion criteria included: (1) literature information: first author, publication date, title, country/region, journal; (2) baseline data: sample size, age, gender, PD stage, and disease duration; (3) design overview: grouping method, treatment modality and duration, outcome measures, treatment efficacy, and follow-up. Disagreements were resolved through discussion initially, with a third party (HZT) consulted if disagreements persisted.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

Two researchers (PWQ and ZRH) independently assessed bias risk using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB2) tool (Sterne et al., 2019). Methodological quality of studies was evaluated based on their randomization process, deviation from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results, and categorized as “low risk”, “high risk”, or “some concerns”. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third researcher (HZT).

Data Synthesis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Revman 5.3 and STATA 17.0 software. For all continuous variables, mean differences (MD) or standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2, with studies categorized as homogeneous (I2≤50%) using a fixed-effects model or heterogeneous (I2>50%) using a random-effects model. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the effects of different oriental exercises and exercise regimens. Sensitivity analyses were conducted as needed. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Egger’s test. Values of P≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Selection

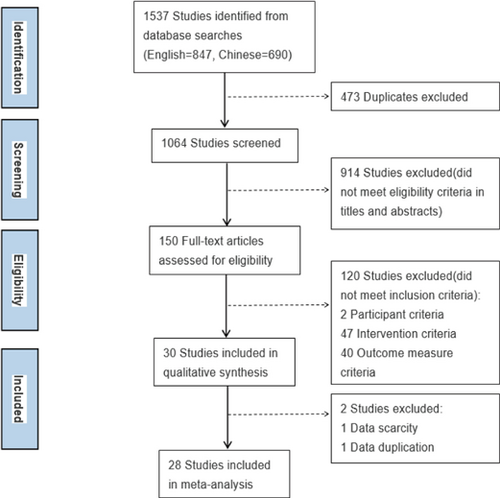

A total of 1537 citations were identified through literature search. After data selection and extraction, 30 were included in the systematic review, of which 28 could be meta-analyzed. The study selection process is in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Study Characteristics

As show in Table 3, there are 24 RCTs and 6 non-RCT studies, with sample sizes ranging from 8 to 330, totaling 2029 patients. The publication years ranged from 2006 to 2023. Among the 30 studies, 21 were conducted in China, 6 in the US, and 1 each in Germany, Italy, and South Korea.

| Study | Design | Duration | Size | Dropout | Mean Age ± SD | Gender (M/F) | H-Y Stage | PD Duration (Y) | Intervention | Control | Frequency | Outcomes | AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burini et al. (2006) Italy | RCT with cross-over | 7W | 26 | 4 | 65.2±6.5 | 9/17 | 2–3 | 10.8±4.6 | Qigong | Aerobic | 45min, 3× | ⑨,② | Aerobic=Musclepain (n=1) |

| Schmitz-Hübsch et al. (2006) Germany | RCT | 16W | T=30C=19 | T=2C=5 | T=64±8C=63±8 | T=24∕8C=19∕5 | 1–4 | T=6.0±5.5C=5.6±3.8 | Qigong | Non | 90min, 1× | MADRS, ② | T=discomfort (n=1) |

| Hackney and Earhart (2009) USA | RCT | 13W | T=13C=14;17;17 | T=4C=5;2;3 | T=64.9±2.3C=68.2±1.4; 66.8±2.4; 64.9±2.3 | T=11∕2C=11∕3; 11/6; 12/5 | 1–3 | T=8.7±1.3C=6.9±1.3; 9.2±1.4; 5.9±1.0 | Tai Chi(Yang-style) | Tango/waltz/non | 1h, 2× | ② | Tango= knee pain(n=1) |

| Cheon et al. (2013) Korea | non-RCT | 8W | T=9C=7∕7 | 9 | T=65.6±7.9C=62.3±6.5/64.9±7.2 | 0/23 | 2–3 | T=6.1±2.9C=5.8±3.4/4.7±4.2 | Tai Chi(Sun-style) | Stretching-Strengthening /non | 1h, 3× | ①⑤, S&E-ADL, PDQL, ⑨, | Non |

| Li et al. (2014) USA | RCT | 24W | T=61C=62∕62 | T=4C=3∕3 | T=68±9C=69±8∕69±9 | T=20∕35C=27∕28;26/29 | 1–4 | T=8±9C=8±9/6±5 | Tai Chi | Resistance/stretching | 1h, 2× | ③∗ | Non |

| Nocera et al. (2013) USA | RCT | 16W | T=15C=6 | T=2C=0 | T=66C=65 | T=7∕8C=4∕2 | 2–3 | T=97MC=82M | Tai Chi (Yang-style) | Non | 1h, 3×/W | ②∗, WMS, L&C VF, ⑤, ⑥ | NR |

| Li and Harmer (2015) USA | RCT | 24W | T=61C=62∕62 | T=4C=3∕3 | T=68±9C=69±8∕69±9 | T=20∕35C=27∕28;26/29 | 1–4 | T=8±9C=8±9∕6±5 | Tai Chi | Resistance/stretching | 1h, 2× | ③∗ | Non |

| Xiao and Zhuang (2016) China | RCT | 24W | T=45C=44 | T=3C=4 | T=66.52±2.13C=68.17±2.27 | T=34∕14C=33∕15 | 1–3 | T=6.1±2.6C=5.4±3.61 | Baduanjin+daily walking | Daily walking | 15min, ≥4× | ⑧∗, ②⑥ | NR |

| Moon et al. (2017) USA | RCT | 6W | T=4C=4 | T=1C=1 | T=61.8±5.7C=68.0±5.3 | NR | T=2.7±0.3C=2.4±0.5 | T=8.0±3.6C=13.3±3.6 | Six-healing sounds | Sham Qigong | home=15–20min, 2×/dgroup=45–60min 1×/W | ⑧∗ | NR |

| Zhu et al. (2020) China | RCT | 12W | T=18C=21 | T=1C=1 | T=68.53±1.9C=67.77±1.72 | T=12∕7C=13∕9 | 1–3 | T=4.7±0.43C=4.0±0.39 | Tai Chi (Yang-style)+RE | Regular exercise | 40–50min, 5× | ②∗, ⑧∗, ①①∗, ①②, ④∗ | Fatigue & dizziness T2 C1;muscle cramps:T1 C1 |

| Moon et al. (2020) USA | RCT | 12W | T=8C=9 | T=8C=7 | T=66.4±8.1C=65.9±5.4 | T=4∕4C=6∕3 | 2 | T=4.25±2.1C=5.33±3.3 | Six-healing sounds | Sham Qigong | home=15–20min 2×/dgroup=45–60min 1×/W | ①∗, ②,, ⑰∗, ⑧①⑤, GAI, ① ④, ①⑥, ⑦, CDT, ⑥ | Back pain (n=1); breathing issue (n=1) |

| Shen et al. (2021) China | RCT | 12W | T=15C=15 | T=1C=1 | T=68.67±4.33C=66.93±3.36 | T=8∕7C=12∕3 | 1–3 | T=6.27±4.5C=7±3.92 | Wuqinxi | Stretching | 90min, 2× | ⑦∗, ④∗, ⑤ (I∗, II) | NR |

| Wang et al. (2022b) China | RCT | 24W | T=23C=22 | T=7C=8 | T=68.83±4.35C=67.95±4.86 | T=7∕16C=10∕12 | 1–2 | T=6.63±4.0C=6.09±3.8 | Wuqinxi | Stretching | 90min, 3× | HADS∗, ⑧∗, ②∗, ④ | NR |

| Li et al. (2022) China | RCT | 12W | T=18C=18 | T=3C=3 | T=66.33±10.89C=69.17±6.48 | T=7∕11C=8∕10 | NR | T=3.27±1.3C=3.75±2.3 | Qigong | Non | 1h, 5×/W | STAI∗ | — |

| Li et al. (2023) China | non-RCT | 3.5Y | T=143C=187 | T=19C=45 | T=66.70±9.02C=66.40±8.13 | T=78∕65C=99∕88 | 1–2.5 | T=4.35±2.0C=3.98±1.9 | Tai Chi (standardized Yi) | Non | 60min, 2× | PDCRS, ① ②, ①①, ②, RBD, ⑧, ESS, SCOPA-AUT, ① | Falling: T18+C39; dizziness: T9+C17 back pain: T3+C15;bone fractures: T6+C17 |

| Wang et al. (2016a) China | RCT | 16W | T=40C=40 | — | T=67.6±8.4C=68.0±8.5 | T=19∕21C=20∕20 | 1–2 | NR | Tai Chi (24 style) | Non | 60min, 14× | ①①∗ | — |

| Guan and Li (2016) China | RCT | 12W | T=30C=30 | — | T=69.61±5.16C=69.52±5.23 | T=17∕13C=14∕16 | 1–3 | T=3.46±1.0C=3.23±1.1 | Tai Chi (24 style) | Non | 60min, 4× | ④∗ | NR |

| Guan et al. (2016) China | RCT | 12W | T=29C=29 | — | T=69.62±5.25C=69.71±5.13 | T=15∕14C=16∕13 | NR | NR | Tai Chi(24 style) | Non | 60min, 4× | ①③∗, WHOQOL-BREF∗ | NR |

| Fan et al. (2017) China | RCT | 8W | T=18C=16 | T=0C=2 | 64.06±8.56 | 21/15 | 3–4 | NR | Qigong | Non | 60min, 5× | POMS∗, ④∗ | NR |

| Liu et al. (2017) China | RCT | 10W | T=23C=18 | T=3C=8 | 57.1±7.0 | 15/26 | 1–3 | 4.1±1.0 | Qigong | Non | 60min, 5× | BAI∗ | NR |

| Ling and Min (2018) China | non-RCT | 1Y | T=50C=50 | — | T=64.5±4.84C=65.5±5.04 | T=20∕30C=23∕27 | T=1.61±0.57C=1.47±0.45 | T=4.42±1.5C=5.00±1.4 | Qigong | Non | 60min, 5× | ①∗ | NR |

| Wu et al. (2018) China | RCT | 16W | T=26C=23 | T=2C=1 | T=62.42±5.37C=64.66±5.74 | T=20∕8C=17∕7 | 1–3 | T=4.75±2.0C=4.25±2.9 | Tai Chi (Yang style) | Regular exercise | 40min, 4× | ④∗, ②∗ | NR |

| Wei et al. (2019) China | non-RCT | 7– 16d | T=28C=22 | 9 | 60.60±10.16 | 39/11 | 1–3 | NR | Baduanjin | Non | 60min/d | ①④∗ | NR |

| Li et al. (2019) China | RCT | 4W | T=33C=33 | 3 | T=62.88±7.50C=62.42±9.37 | T=20∕13C=19∕14 | 1–3 | NR | Baduanjin | Non | 30min/d | ①①∗ | NR |

| Sun and Bi (2020) China | RCT | 6W | T=31C=31 | — | T=63.54±5.53C=64.21±6.14 | T=19∕12C=14∕17 | 1–3 | T=6.34±2.4C=7.21±2.6 | Daoyin | Non | 45min, 5× | ②∗ | NR |

| Zhang (2020) China | non-RCT | 8W | T=47C=39 | — | T=69±5C=68±4 | T=28∕19C=23∕16 | 2–4 | T=2.8±0.9C=2.6±0.7 | Qigong | Non | 30min, 5× | ①∗, ⑰∗ | NR |

| Cao et al. (2021) China | RCT | 8W | T=31C=31 | — | T=62.97±3.27C=62.45±2.87 | T=21∕10C=20∕11 | 3 | T=5.71±1.1C=6.10±0.9 | Wuqinxi | Regular exercise | 30min, 5× | ②∗ | NR |

| Liu et al. (2023) China | non-RCT | 1Y | T=58C=58 | — | T=64.05±4.54C=63.69±5.04 | T=40∕18C=42∕16 | 1–3 | NR | Baduanjin | Non | 30min/d | ②∗ | NR |

| Ding et al. (2023) China | RCT | 12W | T=42C=42 | — | T=69.12±4.06C=69.34±4.02 | T=24∕18C=26∕16 | T=2.34±0.21C=2.29±0.20 | T=4.25±0.4C=4.12±0.4 | Tai Chi (Yang style) | Regular exercise | 60min, 4× | ①③∗ | NR |

| Qu et al. (2023) China | RCT | 8W | T=34C=34 | — | T=65.03±7.56C=64.85±7.68 | T=18∕16C=19∕15 | 1–3 | T=6.11±2.2C=6.24±2.0 | Daoyin | Regular exercise | 30min, 5× | PSQI∗, PSG∗,②∗ | NR |

The utilization of OEs ranked from more to less with Taiji (Tai Chi, n=12), Qigong (n=7) (Burini et al., 2006; Schmitz-Hübsch et al., 2006; Fan et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Ling and Min, 2018; Zhang, 2020; Li et al., 2022), Baduanjin (n=4) (Xiao and Zhuang, 2016; Li et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2023), Wuqinxi (n=3) (Cao et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022b), Liuzijue (n=2) (Moon et al., 2017, 2020) and Daoyin (n=2) (Sun and Bi, 2020; Qu et al., 2023). Most Tai Chi training sessions involved Yang-style (n=8) (Hackney and Earhart, 2009; Nocera et al., 2013; Guan and Li, 2016; Guan et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016a; Wu et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2023), with one study on Sun-style (Cheon et al., 2013), one on self-modified Tai Chi (Li et al., 2023), and two studies without specifying the Tai Chi style (Li et al., 2014; Li and Harmer, 2015). The intervention frequency ranged from 2 to 5 times per week, lasting 30 to 90min each session, with total durations ranging from 2 weeks to 3.5 years. Three studies had durations of over a year (Ling and Min, 2018; Liu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023), all of which were non-RCT studies. Fifteen studies compared Tai Chi exercise with other conventional exercises (e.g. stretching, resistance training, dance), while 15 studies had control groups receiving no exercise therapy.

Thirty studies used the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39) and one used the 8-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-8) to assess QOL. Four studies utilized the Parkinson’s Disease Non-Motor Symptom Questionnaire (NMSQ) to evaluate overall NMS, six studies employed the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and two each used the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Stroop Color and Word Test (SCWT), Trail Making Test (TMT), and Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) to assess cognitive function. Another six studies assessed sleep quality using the Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS), and depression was evaluated in four studies using the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD). two each used Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), anxiety was assessed in two studies using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), and psychological health level was evaluated in two studies using the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90).

Risk of Bias in Studies

RoB2 indicated high risk for nine studies (Cheon et al., 2013; Fan et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Ling and Min, 2018; Wei et al., 2019; Moon et al., 2020; Zhang, 2020; Liu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023), some concerns for 16 studies (Burini et al., 2006; Hackney and Earhart, 2009; Nocera et al., 2013; Xiao and Zhuang, 2016; Guan and Li, 2016; Guan et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016a; Moon et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019; Sun and Bi, 2020; Cao et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022b; Qu et al., 2023), and low risk for five studies (Schmitz-Hübsch et al., 2006; Li et al., 2014; Li and Harmer, 2015; Zhu et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2023). As shown in Fig. 2, 15 studies (50%) appropriately described the randomization process; nine studies (33.33%) mentioned random allocation but did not specify the details of random sequence generation, and six studies were non-randomized (16.66%). Among the studies, 24 (80.00%) did not mention allocation concealment, details of loss to follow-up were insufficient in six studies (20%), and 12 studies (40.00%) reported blinding of outcome assessment. Fourteen studies (46.67%) reported intention-to-treat analysis or no dropouts.

Figure 2. Risk of bias of included studies.

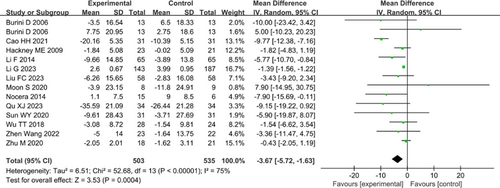

Quality of Life

13 studies involving 882 total patients assessed QOL using PDQ-38, with 1 study of 130 patients using PDQ-8. There was high heterogeneity among the included studies (I2=75%), which significantly decreased after excluding the study by Cao et al. (2021) (I2=11%), but the overall effect remained unchanged. The results (Fig. 3) indicated statistical significance on PDQ (MD: −3.67, 95% CI: −5.72–−1.63, P<0.00001). Subgroup analyses data revealed that Tai Chi (MD: −1.50, 95% CI: −2.53–−0.47, P=0.004), Wuqinxi (MD: −7.76, 95% CI: −13.59–−1.93, P=0.009), and Daoyin (MD: −8.04, 95% CI: −16.21–0.13, P=0.05) significantly reduced PDQ scores, as shown in Table 4. Furthermore, subgroup analysis also revealed that only low-dosage intervention (MD: −4.66, 95% CI: −7.88–−1.44, P=0.005), medium-term (MD: −3.06, 95% CI: −5.18–−0.94, P=0.005), and long-term interventions (MD: −1.39, 95% CI: −1.57–−1.22, P<0.00001) had statistically significant effects on PDQ.

Figure 3. Forest plot of Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ).

| Outcome | Test | OE Type | Studies (Participants) | MD (95% CI) | P-value for Effect | Heterogeneity | Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | PDQ | ALL∗ | 12 (n=1038) | −1.57 (−2.41;-0.73) | 0.002 | P<0.0001, I2=75% | Egger’s test: P=0.061 |

| QIGONG | 3 (n=69) | −0.87 (−12.28;10.54) | 0.88 | P=0.24, I2=31% | |||

| TAICHI∗ | 6 (n=616) | −1.50 (−2.53;−0.47) | 0.009 | P=0.21, I2=30% | |||

| WUQINXI∗ | 2 (n=107) | −7.76 (−13.59;−1.93) | 0.009 | P=0.14, I2=54% | |||

| BADUANJIN | 1 (n=116) | −3.43 (−9.20;2.34) | 0.24 | ||||

| DAOYIN∗ | 2 (n=130) | −8.04 (−16.21;0.13) | 0.05 | P=0.71, I2=0% | |||

| Non-motor symptom in general | NMSQ | ALL∗ | 4 (n=533) | −3.42 (−5.26;−1.59) | 0.0003 | P<0.00001, I2=91% | |

| QIGONG∗ | 2 (n=203) | −3.42 (−5.26;−1.59) | 0.0003 | P=0.15, I2=48% | |||

| TAICHI∗ | 1 (n=330) | −0.52 (−0.60;−0.44) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Cognition | MoCA | ALL∗ | 6 (n=260) | 1.75 (1.46;2.03) | <0.0001 | P=0.51, I2=0% | Egger’s test: P=0.057 |

| QIGONG | 1 (n=34) | 1.28 (−8.63;11.19) | 0.8 | ||||

| TAICHI∗ | 3 (n=151) | 1.50 (0.81;2.18) | <0.0001 | P=0.40, I2=0% | |||

| WUQINXI∗ | 2 (n=75) | 1.80 (1.49;2.12) | <0.0001 | P=0.18, I2=45% | |||

| MMSE | ALL | 2 (n=103) | 2.24 (−1.09;5.57) | 0.19 | P=0.004, I2=88% | ||

| SCWT | ALL∗ | 2 (n=51) | 0.87 (0.49;1.24) | <0.0001 | P=0.49, I2=0% | ||

| TMT | ALL | 2 (n=38) | −9.93 (−27.87;−8.07) | 0.28 | P=0.84, I2=0% | ||

| FAB | ALL∗ | 2 (n=47) | 1.49 (1.16;1.81) | <0.0001 | P=0.24, I2=28% | ||

| Quality of sleep | PDSS | ALL | 6 (n=528) | 1.00 (−0.76;2.77) | 0.28 | P<0.00001, I2=85% | |

| QIGONG | 2 (n=25) | −7.68 (−20.12;4.77) | 0.23 | P=0.18, I2=45% | |||

| TAICHI | 2 (n=269) | 1.07 (−0.19;2.38) | 0.1 | P=0.12, I2=58% | |||

| Neuropsychiatric symptom | HAMD | ALL∗ | 4 (n=515) | −4.27 (−6.85;−1.69) | 0.001 | P<0.00001, I2=99% | |

| BDI | ALL | 2 (n=42) | −0.27 (−4.14;3.61) | 0.89 | P=0.53, I2=0% | ||

| GDS | ALL | 2 (n=67) | 2.50 (−0.97;5.96) | 0.16 | P=0.11, I2=61% | ||

| HAMA | ALL∗ | 2 (n=369) | −0.24 (−0.32;−0.26) | <0.00001 | P=0.63, I2=0% | ||

| SCL-90 | ALL∗ | 2 (n=142) | −0.37 (−0.48;−0.25) | <0.00001 | P=0.88, I2=0% |

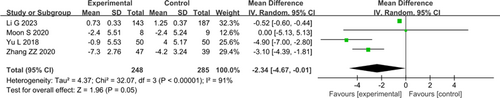

Non-motor Symptom in General

In the assessment of total scores for non-motor symptoms using NMSQ across four studies with 533 patients, significant heterogeneity was observed (I2=91%). After the exclusion of the study by Li et al. (2023), heterogeneity significantly decreased (I2=48%). The pooled results (Fig. 4) indicated a significant effect on NMSQ (MD: −2.34, 95% CI: −4.67–−0.01, P=0.05).

Figure 4. Forest plot of Parkinson’s Disease Non-Motor Symptom Questionnaire (NMSQ).

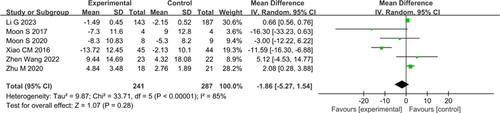

Quality of Sleep

Six studies involving 528 patients used PDSS to evaluate sleep quality. A random-effects model (Fig. 5) showed that OEs lacked statistical significance on PDSS (I2=85%; MD: −1.86, 95% CI: −5.27–1.54, P=0.28).

Figure 5. Forest plot of Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS).

Cognition

For cognitive function assessment, 6 studies with 260 patients used MoCA, and 2 studies with 103 patients used the MMSE. The results indicated that OEs significantly improved MoCA scores (I2=0%; MD: 1.75, 95% CI: 1.46–2.03, P<0.00001), but indicated no statistically significant effects on MMSE (I2=88%; MD: 2.24, 95% CI: −1.09–5.57, P=0.19). Additionally, 2 studies each with 51 patients used SCWT, 38 patients used TMT, and 47 patients used FAB. Fixed-effects models showed that OEs had a significant effect on SCWT (I2=0%; MD: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.49–1.24, P<0.00001) and FAB (I2=28%; MD: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.16–1.81, P<0.00001), but not on TMT (I2=0%; MD: −9.93, P=0.28). Forest plots can be found in Fig. 6.

Figure 6. Forest plot of the cognition.

Subgroup analysis data for MoCA indicated that Tai Chi (MD: 1.50, 95% CI: 0.81–2.18, P<0.0001) and Wuqinxi (MD: 1.80, 95% CI: 1.49–2.12, P<0.00001) had a significant effect. High-dosage (>240min per week) (MD: 2.54, 95% CI: 1.40–3.68, P<0.0001) and medium-term (13–24 weeks) interventions (MD: 2.39, 95% CI: 1.54–3.25, P<0.00001) showed the best effects on MoCA scores.

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

In depression assessment, 4 studies with 515 patients used HAMD, indicated a statistical significance on HAMD (I2=99%; MD: −4.27, 95% CI: −6.85–−1.69, P=0.001). 2 studies each with 42 patients used BDI (I2=0%; MD: −0.27, 95% CI: −4.14–3.61, P=0.89) and 67 patients used GDS (I2=61%; MD: 2.50, 95% CI: −0.97–5.96, P=0.16), which showed no statistically significance. 2 studies with 369 patients used HAM-A to assess anxiety and 2 studies with 142 patients used SCL-90 to evaluate psychological health level. A fixed-effects model showed that OEs had a statistically significant effect on HAM-A (I2=0%; MD: −0.24, 95% CI: −0.32–−0.16, P<0.00001) and SCL-90 (I2=0%; MD: −0.37, 95% CI: −0.48–−0.25, P<0.00001). Forest plots can be found in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. Forest plot of the neuropsychiatric symptom.

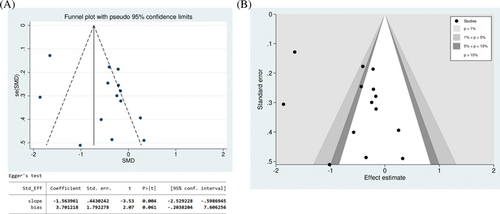

Publication Bias

For outcome indicators with ≥10 included studies, a funnel plot and Egger’s test were conducted for PDQ (Fig. 8A). Despite some asymmetry in the funnel plot, Egger’s test indicated no significant publication bias (P=0.061). Additionally, two scattered studies were located at the bottom of the funnel plot, suggesting a potential small sample effect. A contour-enhanced funnel plot was further constructed to explore potential causes of funnel-plot asymmetry. This indicates that the effect estimates of the included studies predominantly contained values which were not significant (P>10%). This suggests that the observed asymmetry in the funnel plot may be attributable to biases other than publication bias (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Funnel plot to examine publication bias of Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ). (A) Funnel plot and Egger’s test; (B) contour-enhanced funnel plot.

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that after Oriental Exercises (OEs) intervention, there were significant improvements in PDQ, NMSQ, MoCA, SCWT, HAMD, HAM-A, and SCL-90 scores compared to the control groups, indicating a positive impact of OEs on the cognitive level, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and quality of life (QOL) for individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Although rigorous adverse event (AE) reports were not conducted in most of the studies we included, the few AE reports available (Burini et al., 2006; Schmitz-Hübsch et al., 2006; Hackney and Earhart, 2009; Zhu et al., 2020; Moon et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022, 2023) did not indicate any reports of serious AEs, suggesting that OEs is probably safe for individuals with PD.

The QOL among individuals with PD is significantly poorer compared to the healthy population (Zhao et al., 2021). Among the studies reviewed, the most common outcome measure was PDQ (n=13), and the meta-analysis indicated that OEs had a statistically significant positive effect on enhancing the QOL in PD. In terms of exercise selection, Wuqinxi and Qigong showed more significant improvements in QOL than Tai Chi and Baduanjin. Low-dosage (≤180min per week) had better effects than moderate-dosage (180–240min per week) and high-dosage (>240min per week), and a medium-term (13–24 weeks) duration yielded optimal effects. Due to limitations in the types of OEs included and the limited number of studies, other reviews have not shown a significant impact of OEs on the QOL of individuals with PD (Yang et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2021).

Mild cognitive impairment associated with PD occurs in approximately 40% of cases (Baiano et al., 2020) and could progress to Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), thereby significantly affecting patients’ quality of life and social functioning (Janvin et al., 2006). There are various outcome measures for cognitive function assessment, with the most common being the MoCA (n=6) in this study. Tai Chi and Wuqinxi showed advantages in improving MoCA scores compared to Qigong, and high-dosage (>200min per week) and medium-term (13–24 weeks) duration of OEs showed optimal efficacy. However, OEs did not have a significant effect on MMSE. Since MoCA helps identify cognitive deficits in areas such as executive function, visuospatial skills, language, and orientation, it is more suitable for measuring the cognitive status of PD than MMSE (Litvan et al., 2011; Biundo et al., 2016). Therefore, it could be considered that Tai Chi and Wuqinxi, high-dosage, and medium-term duration are optimal for overall cognitive improvement in individuals with PD. Additionally, OEs significantly enhanced the inhibitory control and frontal lobe function in PD, but had no significant effect on executive function assessment.

The underlying mechanism remains unclear. Studies suggest that OEs may increase cortical thickness and overall brain volume, and delay the aging of brain function (Wei et al., 2013). It may also benefit cognitive function and brain structure by elevating plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels (Sungkarat et al., 2018). In addition, it may enhance memory function by regulating resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC), improving processing speed (Tao et al., 2017) and sustained attention by reducing peripheral IL-6 levels and increasing hippocampal volume (Qi et al., 2021). Previous meta-analyses have shown that OEs such as Tai Chi and Qigong can effectively enhance cognitive function in neurological disorders (Wang et al., 2022a), which is consistent with our study results. However, optimal exercise regimens have been recommended, including 60–200 min per week for 6–10 weeks (Wang et al., 2021), or 60–120 min per week of mind–body exercises specifically for cognitive enhancement in the elderly. Discrepancies in these recommendations may be due to the inclusion of non-OEs such as yoga and dance in mind–body exercise-related reviews, as well as the insufficient literature on OEs, indicating the need for further refinement and exploration of specific exercise regimens for OEs in the future.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are one of the most commonly reported NMS in PD, often manifesting prior to formal diagnosis and correlating with accelerated declines in cognitive and motor faculties (Burn, 2002). It was regarded as a key determinant of QOL in PD (Balestrino and Martinez-Martin, 2017). Meta-analysis indicates that the outcome measures related to neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as HAMD (n=4), HAM-A (n=2), and SCL-90 (n=2), showed significant improvement after OEs intervention. However, depression-related BDI and GDS scores did not reach statistical significance. Previous studies have confirmed that HAMD is an effective screening tool for depression in PD (Williams et al., 2012), intimating that OE holds promise in ameliorating anxiety, depression, and psychological well-being in PD. OE emphasizes rhythmic breathing regulation, mindfulness of emptiness, and skeletal muscle relaxation, maximizing physical and mental well-being (Zou et al., 2018) while alleviating symptoms of anxiety and depression (Kong et al., 2022). Studies suggested that the beneficial effects of OEs on neuropsychiatric symptoms may be related to increased plasma adiponectin levels (Chan et al., 2017), and regulation of circRNA expression (An et al., 2019), among other factors, but the specific mechanisms remain unclear. Consistent with our findings, previous meta-analyses reported significant improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms with OEs, with Tai Chi being the most effective (Dong et al., 2023). Due to the relatively limited clinical trials on using OEs to treat neuropsychiatric symptoms in PD, along with insufficient analyzable indicators, more studies in this area may help to provide clarity.

There were several limitations in this study. First, some control groups had different interventions, potentially confounding the outcomes. Second, some included studies had small sample sizes and short intervention periods, potentially reducing the reliability of the analysis results. In addition, in many included studies, the definition of AEs was unclear, leading to a lack of systematic evaluation of OEs safety. Furthermore, the literature search was limited to English and Chinese articles, predominantly from China, raising questions about the generalizability to other populations. Last, the meta-analysis included non-RCTs, some of which had large sample sizes and long intervention periods, which potentially introduced a higher risk of bias.

Although there is increasing evidence regarding the potential advantages of OEs for NNMS and QOL in PD, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, and the quality of the evidence is relatively limited. Future research should conduct larger-scale and rigorous studies to explore the exact therapeutic mechanisms. Considering PD is a chronic progressive disease with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes (Vijiaratnam et al., 2021), personalized treatment regimens should be customized based on distinct PD symptom profiles. Different symptoms and severities may require different types of OEs, exercise dosage, and duration. Future studies should further refine the clinical phenotypes of PD and OE regimens to fully leverage the advantages of OEs in aiding PD rehabilitation.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that OEs are an effective tool for improving cognition, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and QOL in PD. Additionally, this study found that Wuqinxi and Qigong are more suitable for improving the QOL in PD, while Tai Chi and Wuqinxi could significantly improve cognitive function. Low-dosage (≤180min per week), medium-term (13–24 weeks) duration are more effective in improving QOL, while high dosage (>200min per week), medium-term are more suitable for cognitive function. However, the quality of literature included in this meta-analysis is moderate, requiring further rigorous, large-scale, multi-center randomized controlled trials to confirm the therapeutic effects and potential mechanisms of OEs. Stratified, multi-group, adaptive studies should also be designed to ascertain the most suitable OE types, dosages and durations for varying clinical phenotypes, guiding PD patients in selecting optimal OE regimens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. GZY-KJS-2022-026), the Major Innovation Technology Construction Project of Synergistic Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine of Guangzhou (No. 2023-2318), the Special Research Funds for National Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation Center in 2023 (09005656004), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3501402), the Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Young Top-Notch Talents (Team) Unveiling and Leading Project 2023 (23414110Z75) and the Young and Middle-Aged Backbone Cultivation Project Elite Talents 2023 (Clinical Type) (09005650011).

ORCID

Wanqing Peng  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9725-4312

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9725-4312

Renhui Zhao  https://orcid.org/0009-0002-2093-2393

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-2093-2393

Ziting Huang  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9016-1471

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9016-1471

Jingpei Zhou  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6602-4916

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6602-4916

Quan Sun  https://orcid.org/0009-0008-9716-4226

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-9716-4226

Ziyuan Li  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8405-9904

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8405-9904

Xinyu Li  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5360-7154

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5360-7154

Jinyan Yu  https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8718-8959

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8718-8959

Nanbu Wang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7119-8304

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7119-8304

Zhenhu Chen  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7086-0119

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7086-0119