BIRTH ORDER, GENDER AND THE PARENTAL INVESTMENT GAP AMONG CHILDREN

Abstract

Using panel data from the 2001 cohort of the Japanese Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century, this paper examines whether financial investments in children differ by child’s birth order and gender. This study is one of a few studies that use information on actual expenditures on the child under study to infer birth order and gender effects rather than using child outcomes such as educational attainment and health. Moreover, we examine specific types of expenditure on children such as expenditure on regular schooling, extra-curricular activities, extra-educational activities, and pocket money. It is found that in Japan, parents spend more money on (a) their first-born child; (b) their male children when they are of preschool age; and (c) their female children when they are of school age. In contrast, parents’ spending on education-related activities outside regular schools is higher for their first-born child and for girls. However, this gender effect is limited to three children families. Spending on extra-curricular activities and regular schooling is higher for girls and for first-born children. Interestingly, girls receive more pocket money than boys, whereas a first-born child receives less pocket money compared to a later-born child of the same age. With a few exceptions, overall, we observe mostly first-born preference and more of a ‘daughter preference’ than ‘son preference’ in parental investments among Japanese children.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to examine whether financial investments (total expenditure and some of its components including pocket money) in children differ by the child’s birth order and gender. Parent’s investments in their children are crucial for their children’s development and the future outcomes of their children. Parents must make various choices about their investment in their children given their intertemporal budget constraint, their time constraints, and their current budget constraint if they face liquidity constraints. Several studies suggest that parents make different distributions of their resources across siblings (for example, Price (2008)). Black et al. (2005) find that birth order has a significant and negative effect on children’s educational attainment. They also find that there is strong evidence for birth order effects for adult earnings, employment and teenage childbearing, especially for women. Heiland (2009) examines birth order and early scholastic ability (verbal ability), and finds that the verbal ability of the first-born is higher than it is for middle of the birth order children. For Indian children, Barcellos et al. (2014) provide evidence that first-born boys are favored in breastfeeding, childcare time and vitamin supplements.

Overall, most studies indicate that there are positive birth order effects even after controlling for family size effects, that is, a first-born child performs better (see Bjorklund and Salvanes (2011)), although De Haan et al. (2014) indicate that in Ecuador, the educational outcomes of the first-born are poorer than later-born children. However, due to data availability, most of the previous studies examine the outcomes for children such as educational attainment, academic achievement and health status rather than the actual investments in the children. Studies that examine “outputs” are unable to directly answer the question of whether parents in fact change the levels of their inputs, that is, their investment in children, based on their children’s birth order and gender.

When research has been conducted on parental investments in their children, it has typically focused on how much time parents spend with their children. Using the American Time Use Survey, Price (2008) provides evidence that a first-born child receives 20 min more parental time than a second-born child of the same age in a similar family. Sakata et al. (2018) provide evidence that Japanese parents also spend more time with their first-born child. Monfardini and See (2016) and Lehmann et al. (2018) examine whether the better cognitive scores for first-born children can be explained by the time parents spend with their children, but they come to differing conclusions. Research on the effects of birth order on the levels of financial inputs for example, expenditure on children and pocket money is quite rare. In the case of expenditure, one of the key problems is obtaining expenditure spending on each child rather than the total expenditure on all children lumped together. For example, using data from the US Consumer Expenditure Survey, Kornrich and Furstenberg (2013) first identify categories of expenditure that are child-related, and then analyze the factors that determine the spending on all children. In contrast, the survey data used in this paper contains a parental estimate of their overall expenditure on the child that is the subject of the survey, as well as expenditures on regular schooling, extra-educational activities, extra-curricular activities and pocket money for the child in question. Data on these expenditures will enable us to estimate whether financial investments in children differ by child’s birth order and gender for these five expenditure variables.

Gender may matter because parents have gender preferences in relation to children and they may differ across the parents, or there may be some more fundamental differences. For Japan, Kureishi and Wakabayashi (2011) provide evidence suggesting that abortion in Japan is not based on the gender of the child. There is recent evidence for the United States that suggests young boys (boys aged 5 or less) face “unique risks as a result of neurobiological and environmental factors” (Golding and Fitzgerald, 2017, p. 5; McKinney et al., 2017). Garcia et al. (2018) suggest that boys in the United States benefit from high-level childcare whereas girls do not. Both these factors may lead to parents altering their investments in their children based on their gender. Many previous studies for countries other than Japan also show that fathers spend more time with and are more involved with their sons than their daughters (Harris and Morgan, 1991; Lundberg et al., 2007; Mammen, 2011). In contrast, Japanese fathers spread their time evenly between their sons and daughters (Sakata et al., 2018). However, previous studies in Japan suggest that recently, there exist either mixed preference or daughter preference (Kureishi and Wakabayashi, 2011; Fuse, 2013). According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2011, Tables 3–5), 68.7% of Japanese married couples would prefer a daughter if they could have only one child. This may be reflected in different patterns of investments by Japanese parents.

The previous economics literature on pocket money focuses on how it might affect: a child’s performance at school (Barnet-Verzat and Wolff, 2008); the child’s supply of labor (Wolff, 2006); and teaching a child to save (Brown and Taylor, 2016), rather than what determines the amount of pocket money. The annual Halifax (2016) pocket money survey conducted for children in the UK provides evidence that a gender ‘pay gap’ exists even for child pocket money in that sons receive an average of £6.93 per week in pocket money, almost 12% higher than the average £6.16 parents given to daughters. The Halifax (2016) survey is not concerned with birth order effects. The Financial Central Committee (2016) reports details of a Bank of Japan survey of pocket money, but it contains no information related to gender or birth order. Here, we analyze the determinants of the amount of pocket money focusing on both birth order and gender.

Using panel data from the 2001 cohort of the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century (21 seiki shusshoji judan chosa) that is collected by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, this paper examines whether parental financial investments in their children differ by birth order and gender. This study is one of a few studies that use information on actual expenditures on the child under study to infer birth order and gender effects rather than using child outcomes such as educational attainment and health. Moreover, our panel data set allows us to examine specific types of expenditure such as regular schooling, extra-curricular activities, extra-educational activities and pocket money. A key finding is that contrary to the conventional wisdom of son preference and first-born preference, the allocation of financial resources within the family is not so straightforward. It is found that in Japan, parents spend more money in total on their first-born child and at later ages female children. In contrast, parents’ spending on extra-educational activities is higher for their first-born, but the gender effects depend on family size. There are no gender effects for one child or two children families, but we find a daughter preference for three children families. Spending on extra-curricular activities is higher for girls and for the first-born child. Put simply, this paper suggests that siblings are unlikely to receive equal shares of parental investment, that is, we observe a parental investment gap among their children relating to both gender and birth order. Interestingly, girls receive more pocket money than boys, whereas the first-born child receives less compared to a later-born child at the same age. Overall, we tend to observe first child preference and a daughter preference in parental investment among Japanese children. Some evidence is presented to suggest that part of the first-child effect may be attributed to the impact of gender-specific hand-me-downs.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides details of the data used in this paper, while Section 3 describes the model used to analyze the determinants of parent’s investments in their children. Section 4 discusses the empirical results and Section 5 contains the conclusions of the paper.

2. Data

2.1. Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century

The data used in this paper are taken from the 2001 cohort of the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century, which is the first longitudinal survey conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.1 This survey is a mail-in longitudinal census survey which has tracked all babies born in Japan in the periods of 10–17 January 2001, and 10–17 July 2001 which we refer to as January babies and July babies, respectively.2 These babies were sampled from the Live Birth Form of Vital Statistics (Jinko dotai chosa shusseihyo). The first survey which we refer to as Wave 1 was conducted when the babies were about 6 months old, namely, on 1 August 2001 for January babies and on 1 February 2002 for July babies. The number of questionnaires delivered and responses received for Wave 1 are 26,620 and 23,423 for January babies (a response rate of 88.0%), and 26,955 and 23,592 for July babies (a response rate of 87.5%), respectively. With the exception of 2007, this survey has been conducted every year since 2001. For the 2002–2006 surveys (Waves 2–6), the annual survey months continued to be August for January births and February for July babies. From the 2008 survey (Wave 7), the annual survey months for January babies and July babies have been January and July, respectively. We currently have access to every wave up to the 13th wave which relates to 2014. In Wave 13, the children that are the subject of the surveys are aged 13 and are likely to be in their first of junior high school. It should be noted that other siblings in the household are not surveyed in this survey. That is, there is only one child surveyed in each household.

2.2. Variable descriptions

One of the advantages of using the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century is that it asks respondents (and his or her spouse) about the amount of money spent on the child that is the subject of the survey rather than the total amount of expenditure on all children in the family. Since the survey asks directly about the expenditure and certain categories of expenditure for the child surveyed, we can avoid measurement error issues stemming from estimating them from the total amount of spending spent on the children in the family. As stated in Section 3, the outcome variables used in are the total expenditure on the child surveyed, the expenditure on regular schooling, the expenditure on extra-curricular activities of the child surveyed, the expenditure on the extra-educational activities of the child surveyed, and the pocket money given to the child.3 Information on the parent’s total expenditure on the child surveyed is available in each of the 13 waves. The survey asks the respondent how much they spend on the child surveyed in a particular month. The total expenditure includes all the expenditures spent on the surveyed child. The examples of items of expenditure used to illustrate what should be included in total expenditure on the surveyed child vary across the waves depending on the age of the child. As the surveyed child grows up, the illustrative items are modified to reflect the expenses at that stage of the child’s life. For example, in wave 1, the respondents are asked to provide the total expenditures including artificial baby milk, diapers, clothing, childcare, books and toys, whereas in wave 7 where the surveyed child entered primary school, it asks to provide the amount of all the expenditures spent on the surveyed child including expenditures on after school childcare, medical expenses, clothing, regular schooling and extra-educational activities.

The survey is structured in a way that it first asks about total expenditure and the respondents are asked to include “all expenses such as after-school childcare, medical expenses, clothing, schooling and extra-educational activities.” Then the respondents are asked to provide details of expenditure for some of the sub-categories. From wave 8 (2009), the survey asks how much the respondent spent on regular schooling, extra-curricular activities and extra-educational activities, respectively.

For expenses on regular schooling, the respondents are asked to include “textbooks, school materials, supplied meals and school fees.” It should be noted that school fees are only applicable for children attending private schools, and a large majority of Japanese parents send their children to their local public schools during their compulsory education years (from the age of 6 to the age of 15). For example, in 2019 only 1.2% of Japanese children aged 6–12 attended private primary schools, and 7.4% of children aged 13–15 attended private junior high schools (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Science, 2019). For the large majority of children who attend public school, the main costs for school are fixed costs for textbooks, school materials and supplied meals, and parents cannot ‘invest’ more on these items. Notwithstanding this, we still observe some systematic behavior in expenditure on regular schooling.

The extra-educational activities are education-related activities outside regular schools, for example, cram schools, private tutoring and correspondence/online courses. These activities aim to improve the scholastic performance of their children including in areas like mathematics, science and social science. Japanese parents use extra-educational programs to help their children prepare for future entrance exams for high school and university. Extra-curricular activities include gymnastics, swimming, baseball/softball, soccer, tennis, kendo, judo, ballet, dance, English conversation classes, abacus, calligraphy, music lessons, handicraft, flower arranging (ikebana) and the tea ceremony. Information on these two categories is available for waves 8–13.

The information on the amount of pocket money for the child surveyed is available for 2013 (wave 12) and 2014 (wave 13). The 2013 survey asks parents how much pocket money they give to their child on average per month, while the 2014 survey asks the same question to the child.

It should be noted that information on the annual labor income for mothers and fathers and their other income, which is used to calculate the household income, is only available for waves 2, 4, 5, 7, 10, 12 and 13, and relates to the year prior to the year of the survey, so that for wave 13 which was collected in 2014, the income data relates to 2013. Requiring the availability of both the expenditure and income data means the analysis for: total expenditure covers children aged between 18 months and 13 years (with gaps); regular schooling, extra-curricular activities and extra-educational activities relates to children aged 10, 12 and 13; and pocket money relates to children aged 12 and 13. The vacancy rate is measured using job-offers-seekers ratio for the relevant prefecture and is taken from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s Employment Referrals for General Workers. The exact definitions of all variables used in the analysis are contained in Appendix A.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model

Our main objectives are to estimate the birth order and gender effects on parental investment in a child. The following model for parental investment in a child is estimated,

3.2. Sample selection

Our initial sample selection rules for our regression analyzes are as follows: We confine the sample to those households which have at least two children and exclude families where the mother and father do not live together, and exclude families which have multiple births. For total expenditure, observations, where the reported expenditure on the child was zero, are excluded. To remove potential outliers, the top 1% of values for total expenditure, expenditure on regular schooling, expenditure on extra-educational activities, expenditure on extra-curricular activities and pocket money are excluded from the sample when that category of expenditure is being analyzed. Finally, restricting the sample to those who answer the questions providing all the necessary information reduces the final number of observations to 170,985 for the total expenditure analysis when children aged between 18 months and 13 years are analyzed together, 84,798 for the analysis of the expenditure on regular schooling, 61,207 for the analysis of the expenditure on extra-curricular activities, 60,972 for the analysis of expenditure on extra-educational activities, and 41,929 for the analysis of pocket money.

4. Estimated Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

All regression results reported in this section are estimated using STATA version 16 (StataCorp, 2019). Table 1 displays some descriptive statistics for the key variables used in the regression analysis with the continuous variables reported in Panel (a) and the dummy variables reported in Panel (b).

| Variable | Sample Size | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Continuous variables | |||||

| Expenditure on child (1000 Japanese yen, monthly) | 170,985 | 35.481 | 26.214 | 2 | 249 |

| Log of expenditure on child | 170,985 | 3.348 | 0.667 | 0.693 | 5.517 |

| Expenditure on regular schooling (1000 Japanese yen, monthly) | 84,798 | 9.364 | 8.379 | 0 | 71 |

| Log of expenditure on regular schooling | 84,798 | 2.162 | 0.560 | 0 | 4.277 |

| Expenditure on extra-curricular activities (1000 Japanese yen, monthly) | 61,207 | 7.680 | 7.654 | 0 | 44 |

| Log of expenditure on extra-curricular activities | 61,207 | 1.678 | 1.098 | 0 | 3.807 |

| Expenditure on extra-educational activities (1000 Japanese yen, monthly) | 60,972 | 8.207 | 11.749 | 0 | 79 |

| Log of expenditure on extra-educational activities | 60,972 | 1.426 | 1.323 | 0 | 4.382 |

| Pocket money (Japanese yen, monthly) | 41,929 | 958.518 | 871.672 | 0 | 4800 |

| Log of pocket money | 41,929 | 5.326 | 2.987 | 0 | 8.477 |

| No. of siblings | 170,985 | 1.376 | 0.614 | 1 | 10 |

| Household income (10,000 Japanese yen) | 170,985 | 648.075 | 502.959 | 0 | 73,000 |

| Log of household income | 170,985 | 6.347 | 0.537 | 0 | 11.198 |

| Mother’s age | 170,985 | 36.951 | 5.955 | 17.25 | 61.167 |

| Father’s age | 170,985 | 39.067 | 6.697 | 17.833 | 77.75 |

| Vacancy rate | 170,985 | 0.843 | 0.296 | 0.26 | 1.67 |

| Sample size | Fraction | ||||

| (b) Dummy variables | |||||

| Boy | 170,985 | 0.524 | |||

| First child | 170,985 | 0.334 | |||

| Mother’s university degree | 170,985 | 0.147 | |||

| Father’s university degree | 170,985 | 0.388 | |||

| Co-residence with a grandparent | 170,985 | 0.231 | |||

| July dummy | 170,985 | 0.503 | |||

Table 2 provides some simple evidence on how the five types of expenditure change as birth order changes when no sample selection rules are applied and the control variables are not taken into consideration. For total expenditure, expenditure on extra-curricular activities and expenditure on extra-educational activities, the average spending falls as birth order increases for the first three births. In contrast, the average amount of pocket money increases for the first four births. As will be seen in our regression analyses, even when account is taken of the control variables in Equation (1) these findings are by and large maintained.

| Total Expenditure | Expenditure on Regular Schooling | Expenditure on Extra-Curricular Activities | Expenditure on Extra-Educational Activities | Pocket Money | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Order | Sample Size | Mean | Sample Size | Mean | Sample Size | Mean | Sample Size | Mean | Sample Size | Mean |

| 1 | 233,968 | 42.0 | 62,512 | 10.9 | 105,154 | 9.4 | 86,358 | 8.1 | 29,658 | 1110.0 |

| 2 | 178,123 | 36.7 | 47,868 | 10.0 | 79,824 | 8.3 | 65,414 | 7.1 | 22,809 | 1129.6 |

| 3 | 56,883 | 32.8 | 15,133 | 9.4 | 24,151 | 7.1 | 19,569 | 5.5 | 7101 | 1131.4 |

| 4 | 8514 | 30.7 | 2230 | 9.1 | 3199 | 6.4 | 2514 | 4.8 | 1053 | 1307.2 |

| 5 | 1406 | 27.5 | 349 | 9.3 | 498 | 5.9 | 387 | 3.5 | 159 | 1116.0 |

Table 3 provides some simple evidence on the gender differences for the five types of expenditure. For total expenditure, expenditure on regular schooling, expenditure on extra-curricular activities and pocket money, the average spending is higher for girls, whereas the average spending on extra-educational activities is higher for boys. As will be seen in Section 4, even when account is taken of the control variables in Equation (1), these findings are by and large maintained.

| Variable | Total Expenditure | Expenditure on Regular Schooling | Expenditure on Extra-Curricular Activities | Expenditure on Extra-Educational Activities | Pocket Money | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Boys | Girls | -Value | Boys | Girls | -Value | Boys | Girls | -Value | Boys | Girls | -Value | Boys | Girls | -Value |

| Mean | 38.2 | 39.2 | 3.67*** | 10.2 | 10.5 | 3.47** | 7.9 | 9.5 | 20.82*** | 7.5 | 7.2 | 3.03*** | 1104.2 | 1145.0 | 3.13*** |

| Sample size | 248,796 | 230,577 | 66,366 | 61,824 | 109,511 | 103,444 | 89,506 | 84,823 | 31,449 | 29,378 | |||||

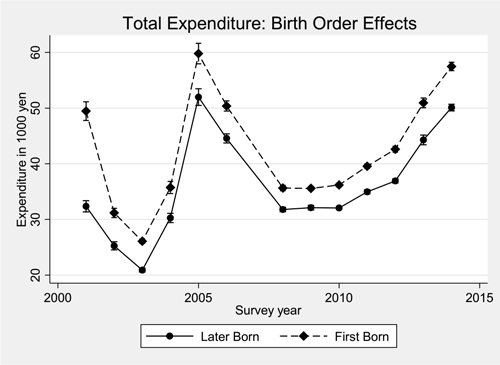

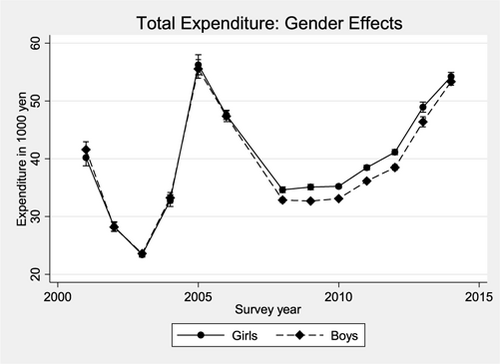

Figures 1 and 2 plot the average of total expenditure for each survey year for the first-born child and later-born children (Figure 1), and for girls and boys (Figure 2) without any sample selection criterion imposed. In all the survey years, the average expenditure on the first-born is higher than for later-born children. In contrast, up to and including 2006 there is little difference in the average spending on boys and girls, but from 2008 the average spending on girls is higher. For average expenditure, the birth order effects appear to be far larger than any gender effects. Similar figures for expenditure on regular schooling, expenditure on extra-curricular activities and expenditure on extra-educational activities are available in Online Supplementary Material.

Figure 1. Total Expenditure: Birth Order Effects

Figure 2. Total Expenditure: Gender Effects

4.2. Estimation results

Since we have excluded all the zero observations on total expenditure, Table 4 presents the results of estimating Equation (1) by ordinary least squares (OLS) for the log of parental expenditure on the child surveyed using all the data (column (4.1)) and using the data for prior to 2007 (column (4.2)) and after 2007 (column (4.3)). Standard errors are clustered at the household level. For a child to be included in the samples used in Table 4, he/she must have at least one sibling. Using all the data, the estimated coefficient for the first child dummy is positive and statistically significant, and suggests that Japanese parents spend 5.8% points more on their first-born than on their second or later children when they are of the same age. When all the data is used, the sample period spans the period 2002 until 2013, that is, children aged from 18 months to 13 years, so it is worth splitting the data to see if there is any structural change in the relationship. We split the sample into observations before the children have started primary school (before 2007), and after the children have started primary school (after 2007) and estimate Equation (1) separately using data before and after 2007, respectively. While no change is observed in the sign of the estimated coefficient of the first-born dummy and its significance, it is important to note that prior to 2007, that is, for younger children, spending is only 1% higher for boys. After 2007, total spending is significantly higher for girls (4.5% points). In interpreting the results reported in Table 4, it is important to remember that time dummies are included, so that since all the children analyzed are born in 2001, the time dummies act as age dummies. That is, in this analysis the expenditure on children is allowed to change over time, but in the two subperiods prior to 2007 (children up preschool age) and after 2007 (children of school age) it assumed that the respective differences between male and female children are held constant. Figure 2 suggests the average spending on boys is less than the spending on girls at each age from age 7 (2008). If Equation (1) is estimated separately for each age, that is, the difference between spending on male and female children is allowed to change with the age of the child, we still find that expenditure on female children is significantly higher than on male children at each age after 2007.7

| Total Expenditure | Regular Schooling | Extra-Curricular Activities | Extra-Educational Activities | Pocket Money | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Year 2007 | Year 2007 | |||||

| OLS | OLS | OLS | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | |

| (4.1) | (4.2) | (4.3) | (4.4) | (4.5) | (4.6) | (4.7) | |

| Boy | 0.0179*** | 0.0092* | 0.0445*** | 0.0156*** | 0.1626*** | 0.0362*** | 0.1324*** |

| [0.004] | [0.005] | [0.005] | [0.004] | [0.009] | [0.010] | [0.031] | |

| First born | 0.0579*** | 0.0352*** | 0.0736*** | 0.0328*** | 0.1344*** | 0.1400*** | 0.1813*** |

| [0.005] | [0.007] | [0.005] | [0.005] | [0.010] | [0.011] | [0.035] | |

| No. of siblings | 0.0793*** | 0.0641*** | 0.0897*** | 0.0140*** | 0.0184*** | 0.1714*** | 0.1374*** |

| [0.003] | [0.005] | [0.004] | [0.004] | [0.007] | [0.009] | [0.026] | |

| Log of household income | 0.1778*** | 0.1490*** | 0.2208*** | 0.0497*** | 0.1129*** | 0.3385*** | 0.1409*** |

| [0.005] | [0.006] | [0.007] | [0.006] | [0.010] | [0.013] | [0.034] | |

| Mother’s age | 0.0021*** | 0.0001 | 0.0040*** | 0.001 | 0.0103*** | 0.0110*** | 0.0211*** |

| [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.002] | [0.002] | [0.006] | |

| Mother’s university degree | 0.0741*** | 0.0612*** | 0.0817*** | 0.0059 | 0.0520*** | 0.0291** | 0.0994** |

| [0.006] | [0.008] | [0.007] | [0.007] | [0.013] | [0.013] | [0.045] | |

| Father’s age | 0.0026*** | 0.0031*** | 0.0023*** | 0.0011* | 0.0024* | 0.0060*** | 0.0104** |

| [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.004] | |

| Father’s university degree | 0.0446*** | 0.0135** | 0.0967*** | 0.0006 | 0.0709*** | 0.1682*** | 0.1182*** |

| [0.005] | [0.006] | [0.006] | [0.005] | [0.010] | [0.011] | [0.035] | |

| Co-residence with a grandparent | 0.0214*** | 0.0416*** | 0.0000 | 0.0143*** | 0.0133 | 0.0138 | 0.1433*** |

| [0.005] | [0.006] | [0.006] | [0.005] | [0.011] | [0.013] | [0.041] | |

| Vacancy rate | 0.0427*** | 0.2663*** | 0.0055 | 0.0188 | 0.1389*** | 0.1971*** | 0.2117 |

| [0.013] | [0.025] | [0.015] | [0.016] | [0.045] | [0.051] | [0.391] | |

| July dummy | 0.0791*** | 0.1161*** | 0.0426*** | 0.1214*** | 0.0967*** | 0.1014*** | 0.0401 |

| [0.004] | [0.005] | [0.005] | [0.004] | [0.009] | [0.010] | [0.031] | |

| Prefecture dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size | 170,985 | 84,895 | 86,090 | 84,798 | 61,207 | 60,972 | 41,929 |

| Number of left censored observations | 1,171 | 14,732 | 25,486 | 9,740 | |||

| Number of id | 35,522 | 32,643 | 28,818 | 28,732 | 26,099 | 26,118 | 24,191 |

| R-squared or pseudo R-squared | 0.229 | 0.151 | 0.198 | 0.093 | 0.067 | 0.045 | 0.007 |

| Value of maximized log-likelihood | 151057.8 | 84112.8 | 63389.1 | 66627.4 | 91383.8 | 94106.7 | 99556.5 |

The four components of expenditure have a large number of zero observations, so these equations are estimated using a Tobit estimator, and the estimated marginal effects of each variable are reported. Standard errors are clustered at the household level. When we look at the results for the four components of expenditure that are available, expenditure on regular schooling (column (4.4)) extra-curricular activities (column (4.5)), expenditure on extra-educational activities (column (4.6)), and pocket money (column (4.7)), respectively, there are some interesting differences both with respect to gender and birth order effects. For first-born children, spending on regular schooling, extra-curricular activities and extra-educational activities are significantly higher than for later-born children. Parents spend 3.3% more on regular schooling, 13.4% more on extra-curricular activities and 14.0% more on extra-educational activities for their first-born child than for later children of the same age. In contrast, later-born children receive more pocket money than a first-born child when they are of identical ages. The first-born receives 18.1% less pocket money. One interpretation of this outcome is that the amount of pocket money the first-born sibling receives rises with their age, and then parents may want to equalize the pocket money among children and try to give higher order children a similar amount of pocket money to the first-born child. An alternative interpretation is that higher order children negotiate the amount of their pocket money with their parents when they have elder siblings, using the amount paid to the elder sibling as their initial request.

Examining the gender effects for the individual expenditure categories, we observe that parents spend significantly more on regular schooling, extra-curricular activities, extra-educational activities and pocket money for girls. In fact, spending on boys is 1.6% lower for regular schooling, 16.3% lower for extra-curricular activities, and 3.6% lower for extra-educational activities. Responses to questions in some years relating to the nature of the extra-curricular activities give us some insights into these gender differences. In Wave 10 when the children are 10 years old, on average girls engage in 1.36 extra-educational activities while boys engage in 1.29. Although we do not have the information on how much parents spend on each activity of extra-curricular activities, the survey data provide information on their participation rates. Examining participation rates in the various activities produces significant gender differences. Seventeen percentage and 21% of boys play baseball and soccer while 1% girls participate in these activities. In contrast, 24% of girls and 13% of boys engage in calligraphy and 39% of girls and 9% of boys engage in classical music. Thus, the gender differences in expenditures may reflect the cost differences in activities which each gender prefers. Another interpretation is that parents may decide to invest more in girls in the knowledge that girls will be worse off in the labor market, or the decisions by parents to spend more on girls may itself be the cause of the gender gap.8 In addition, girls also receive 13% more pocket money, which contrasts with the findings for the United Kingdom reported in the Halifax (2016) pocket money survey which suggests that British boys receive more pocket money than girls. Although there is a significant gender gap for wages in favor of men in Japan, this is not the case for pocket money.

On birth order effects, apart from pocket money, our findings are in line with previous studies: the first child gets more. On gender effects, previous studies in Japan show mixed preference or daughter preference (Kureishi and Wakabayashi, 2011; Fuse, 2013). However, among neighbor Asian countries, son preference appears to persist. In South Korea, boys receive higher expenditures on private academic education (Choi and Hwang, 2015, 2020). Similarly in China, sons receive more education than daughters (Wang et al., 2020). In contrast, our findings show that girls receive more financial investment from parents.

4.3. Robustness check

As a robustness check of the results in Table 4 which covers families with two or more children, Table 5 presents the results for the gender and birth order variables for families with one, two and three children separately. When three children families are analyzed, a second-born dummy taking the value 1 if the child is the second-born and zero otherwise is also included as an explanatory variable. For families with one child which are not included in the analysis in Table 4, there are no gender effects for extra-educational activities, but the other gender effects for these families are consistent with those observed in Table 4. In contrast to Table 4, we do not observe any gender effects for extra-educational activities in families with two children. In families with one or three children, total expenditure for young children is the same for boys and girls. Third born children receive even less total spending, spending on extra-curricular activities and spending on extra-educational activities than their earlier born siblings. The other effects are the same as found in Table 4.

| Total Expenditure | Regular Schooling | Extra-Curricular Activities | Extra-Educational Activities | Pocket Money | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year2007 | Year2007 | ||||||

| Family Size | OLS | OLS | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | |

| 1 Child family | Boy | 0.0066 | 0.0750*** | 0.0278** | 0.2088*** | 0.0101 | 0.1715** |

| [0.007] | [0.014] | [0.013] | [0.026] | [0.028] | [0.085] | ||

| Sample size | 46,740 | 11,977 | 11,675 | 8,297 | 8,257 | 5,698 | |

| 2 Children family | Boy | 0.0121** | 0.0474*** | 0.0173*** | 0.1908*** | 0.0121 | 0.1136*** |

| [0.006] | [0.006] | [0.005] | [0.010] | [0.011] | [0.034] | ||

| 1st born | 0.0165** | 0.0683*** | 0.0296*** | 0.1305*** | 0.1088*** | 0.1818*** | |

| [0.007] | [0.007] | [0.006] | [0.011] | [0.012] | [0.038] | ||

| Sample size | 61,852 | 54,679 | 53,767 | 39,182 | 38,996 | 26,738 | |

| 3 Children family | Boy | 0.0131 | 0.0376*** | 0.0137* | 0.0937*** | 0.0345** | 0.1397*** |

| [0.011] | [0.008] | [0.008] | [0.014] | [0.014] | [0.050] | ||

| 1st born | 0.0676*** | 0.1265*** | 0.0568*** | 0.1764*** | 0.1692*** | 0.1375* | |

| [0.023] | [0.013] | [0.012] | [0.022] | [0.022] | [0.077] | ||

| 2nd born | 0.0268* | 0.0528*** | 0.0138 | 0.0601*** | 0.0781*** | 0.0203 | |

| [0.014] | [0.011] | [0.010] | [0.019] | [0.019] | [0.066] | ||

| Sample size | 19,688 | 26,717 | 26,380 | 18,879 | 18,842 | 12,926 | |

| Equality test (p value) | 0.069 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.013 | |

4.4. Discussion

There are several potential reasons why parents spend more on their first-born child. The first relates to learning by doing. For their second and subsequent children, parents have some experience with raising children and so may engage in less spending. The second relates to different parental preferences between their first child and later children. Alternatively, the effect of hand-me-downs from the first to subsequent children may reduce expenditure for second and later children. In order to investigate this last possibility a little further, it is useful to distinguish gender-specific durable goods, for example, clothes, and gender-irrelevant goods, for example, prams. In order to pick up the possible impact of the former type of hand-me-downs, we investigated whether there were differences in expenditure between households where the first two children are of the same gender and when they are of different genders. In the models for the five categories of expenditure, we added a same sex sibling dummy, Same sex siblings, that is, a 0–1 dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the first two children have the same sex. In addition, this dummy interacted with the first-born dummy. The results for the key variables are presented in Table 6. For total expenditure and expenditure on extra-curricular activities, it is found that compared to households with children of different gender, expenditure on a child in a family with children of the same gender tends to be lower, but the first child in this household still receives higher total expenditure and spending on extra-curricular activities but the size of the first child effect is not necessarily smaller than that reported in Table 5 for these families. These findings are consistent with gender-specific hand-me-downs. However, it is worth pointing out that even after taking account of this effect, the first child still receives more resources, so gender-specific hand-me-downs cannot explain all of the first-born effect.

| Total Expenditure Year 2007 | Total Expenditure Year 2007 | Regular Schooling | Extra-Curricular Activities | Extra-Educational Activities | Pocket Money | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | OLS | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | |

| Boy | 0.0123** | 0.0470*** | 0.0172*** | 0.1971*** | 0.0290** | 0.1202*** |

| [0.006] | [0.006] | [0.005] | [0.011] | [0.013] | [0.038] | |

| First born | 0.0135 | 0.0528*** | 0.0262*** | 0.1167*** | 0.1372*** | 0.2628*** |

| [0.010] | [0.009] | [0.008] | [0.016] | [0.018] | [0.055] | |

| Same sex siblings | 0.001 | 0.0339*** | 0.0099 | 0.0643*** | 0.0135 | 0.1762*** |

| [0.008] | [0.008] | [0.008] | [0.016] | [0.018] | [0.053] | |

| Same sex siblings * first born | 0.0073 | 0.0323*** | 0.0071 | 0.0441** | 0.0100 | 0.1389* |

| [0.012] | [0.012] | [0.011] | [0.022] | [0.025] | [0.076] | |

| Sample size | 61,378 | 54,679 | 53,767 | 39,182 | 38,996 | 26,738 |

5. Concluding Remarks

This paper has examined whether financial investments in children differ by child’s birth order and gender. Unlike previous studies which mainly examine the effects of birth order on the outcomes of children such as educational attainment, academic achievement and health status, this paper rather focuses on the actual investments in children, namely total expenditure, and four components of expenditure for the child surveyed, expenditure on regular schooling, expenditure on extra-curricular activities, extra-educational activities and pocket money. In doing so, we provide a clearer picture of the channel between the birth order and gender of the child and their later outcomes. To sum up our findings, in total, the Japanese parents spend more money on their first-born child. They spend more on boys in their early years, but girls get more in their later years. In contrast, parental spending on educational related activities outside regular schools is higher for their first-born child and for girls. The gender effects stem from three children families. Spending on extra-curricular activities is higher for girls and for first-born children. Interestingly, girls receive more pocket money than boys, whereas a first-born child receives less pocket money compared to a higher order child of the same age. Our findings suggest that the parental resources are distributed unevenly among children. We observe a parental investment gap among their children based on both gender and birth order. With the exception of pocket money, we observe a first-born preference in parental investments. Daughter preference is prevalent in parental investment among Japanese children. Conventional wisdom suggests a son preference and a first-born preference, but interestingly, the data suggests that parents are in fact investing more in girls than boys. We cannot know whether the gender differences in parental investments come from the supply side and/or demand side. For the supply side, parents may make a conscious choice in investment in daughters because they prefer daughters more or as we discussed, parents may decide to invest more in girls because they know girls will be disadvantaged in the labor market in the future. For the demand side, girls may be more demanding and/ or prefer more expensive activities. To answer this requires further investigation.

It is worth noting that the result in this paper that parents spend more money on their male children when children are young and their female children when children are older is based on one cohort of children. Although it is possible that spending on male and female children of the same age changes over time, with only one cohort we cannot make any judgment about this. Over time, as data for younger children from the 2010 cohort of the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21 Century becomes available it will be possible to compare the results in this paper with a later cohort and determine how important these changes over time are.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our thanks to two anonymous referees for their helpful and constructive comments that have led to a significant improvement in the paper. The authors would also like to thank Yasuhiro Tsukahara and participants in the 22nd Eurasia Business and Economics Society (EBES) Conference (Rome), the 16th International Conference of the Japan Economic Policy Association (Naha), the 11th International Conference of the Thailand Econometric Society (Chiang Mai), the 12th Joint Symposium of Five Leading Asian Universities (Singapore), the 85th International Atlantic Economic Society Conference (London) and a seminar at Keio University for their helpful and constructive comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The data used in this paper come from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century (21 seiki shusshoji judan chosa) and the Live Birth Form of Vital Statistics (Jinko dotai chosa shusseihyo). The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance provided by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant in Aid for Scientific Research (B) Nos. 15H03363 and 21H00721. The funding source had no involvement in any stage of this research. The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Australian Institute of Family Studies or the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

DECLARATIONS

Funding

This study was funded by two Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants in Aid for Scientific Research (B) (Grant Numbers 15H03363 and 21H00721).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they do not have any actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this research. No ethic approval was required for this study.

Availability of data and material

The data used in this paper, the 2001 cohort of the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century and the Live Birth Form of Vital Statistics, can be obtained by applying to the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Code availability

The authors are ready to make available their STATA code for reading the data and obtaining the results in this paper.

Online Supplementary Material

This material is available at http://www.worldscientific.com/doi/suppl/10.1142/S0217590822500515

Notes

1 The questionnaires for the first 15 waves of the survey are available in Japanese at the following URL: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/chousahyo/index.html#00450043 (Accessed 7 Jan 2022). The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has provided some information in English relating to simple analyses of the data contained in the first 14 waves at the following URL: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/vs03.html (Accessed 7 Jan 2022). Sakata et al. (2015) provide a summary of this survey in Japanese.

2 In addition to the 2001 cohort of the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21stCentury that is the subject of analysis in this paper, there is another cohort that starts with children born in 2010. As of 2021, there are only 11 waves of data for this 2010 cohort. As a result, there is not yet sufficient amount of information in the 2010 cohort to undertake an analysis similar to the one we have undertaken for the 2001 cohort.

3 Since there are zero observations for expenditure on a child’s extra-curricular activities and extra-educational activities and for a child’s pocket money, we added one to each observation before taking logs.

4 Since and are two of the key variables of interest and they are not time dependent, we do not consider a fixed-effects approach.

5 An alternative justification for including prefectural dummies is that the probability of having a male child may differ by geographical location. If we examine the ratio of males to females in the age group 0–4 years, then according to the National Census for 2000, it is 1.05 for Japan as a whole, that is, there are slightly more boys than girls. The ratio ranges from a minimum of 1.03 for Kagoshima to a maximum of 1.07 for Iwate, so there does not seem to be such a large difference across prefectures in the male to female ratio. Furthermore, Japan’s Maternity Health Act (Botai Hogo Ho) provides that abortions are allowed up to the 22nd week of a pregnancy, so that from a timing perspective having an abortion after the gender of the fetus is known is difficult.

6 We also conduct the analysis replacing the prefectural dummies by city size dummies, but there are no major qualitative changes in the results. These results are not reported.

7 These results are available in Table OSM1 of Online Supplementary Material.

8 There is some conflicting evidence relating to the desires of Japanese parents in relation to educating male and female children. The Japanese responses in Wave 6 of the World Values Survey in answer to the statement “A university education is more important for a boy than a girl” (question v52) suggest that only 16% of respondents agree with the statement, and the majority disagree with it. (Accessed 10 July 2020. Available from URL: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp). National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2017, Table III-1-12) reports that there is at least a 10% point difference in the proportion of couples who want a son to get at least a university education compared to a daughter.

Appendix A. Definitions of Variables

| Variable Name | Definition |

|---|---|

| Expenditure | Total expenditure on the child in question (1000 yen) |

| log of expenditure | log (Expenditure) |

| Expenditure on regular schooling | Expenditure on textbooks, school materials, supplied meals and school fees |

| log of expenditure on regular schooling | log (Expenditure on regular school+1) |

| Expenditure on extra-curricular activities | Expenditure on extra-curricular and sporting activities, where these activities include gymnastics, swimming, baseball/softball, soccer, tennis, kendo, judo, ballet, dance, English conversation, abacus, calligraphy, music lessons (piano, etc.), handicraft, flower arranging (ikebana), and the tea ceremony (1000 yen) |

| log of expenditure on extra-curricular activities | log (Expenditure on extra-curricular activities+1) |

| Expenditure on extra-educational activities | Expenditure on extra-educational activities where these are educational related activities outside regular schools, for example, cram schools, private tutoring, and correspondence/online courses (1000 yen) |

| log of expenditure on extra-educational activities | log (Expenditure on extra-educational activities+1) |

| Pocket Money | Pocket money given to the child (yen) |

| log of pocket money | log (Pocket Money+1) |

| First child | 0–1 dummy variable taking the value of unity if the child surveyed was the first-born child, and 0 otherwise |

| Boy | 0–1 dummy variable taking the value of unity if the child was a boy, and 0 otherwise |

| No of siblings | Number of brothers and sisters of the child surveyed |

| Household income | Sum of father’s and mother’s labor income and other income for the previous year (10,000 yen) |

| Log of household income | log (Household income+1) |

| Mother’s age | Age of the mother (years) |

| Mother’s university degree | 0–1 dummy variable taking the value of unity if the mother has a university or higher degree, and 0 otherwise |

| Father’s age | Age of the father (years) |

| Father’s university degree | 0–1 dummy variable taking the value of unity if the father has a university or higher degree, and 0 otherwise |

| Coresidence with a grandparent | 0–1 dummy variable taking the value of unity if there is at least one grandparent co-residing with the child, and 0 otherwise |

| Vacancy rate | Job offers seekers ratio for the prefecture where the child lives |

| July dummy | 0–1 dummy variable taking the value of unity if the child was born in July, and 0 otherwise |

| Same sex siblings | 0–1 dummy variable taking the value of unity if all the children have the same sex, and zero otherwise (Only defined for two children families) |