AN INTEGRATED THEORY OF HOUSEHOLD BEHAVIOR

Abstract

This paper presents an integrated model of household behavior, in which households derive utility not only from flow choices (of goods and leisure activities) but also from stock variables representing the status in health, psychological stress, social standing/reputation, political affiliation, religious identity, and any other status deemed relevant for their well-being. To attain the status in any of these dimensions, proper investment is necessary in accordance with a suitable mediating function that connects flow choices to the status in question. We depart from the position that statuses activate motivation, thereby affecting the efficiency of activities including working time. In particular, health not only yields utility of its own kind but also affects the productivity of households, thereby expanding their budget sets and raising the utility they attain now and in the future. Health, however, must be attained and maintained, and this has to be accomplished in accordance with a plausible health-production function defined on the space of goods and leisure activities. The same can be said about knowledge and skill acquisition, which requires investment of certain activities and goods through an appropriate mediating function. Similar relationships also hold for social, psychological, and other statuses, which can only be acquired through proper mediating functions. While the utility calculus appears complex, we demonstrate that the optimum choice of goods and leisure activities is guided by the rationality principle that requires that the composite marginal utility, defined as the total of all marginal utilities from the entire sources of utility, direct or mediated, be balanced with properly measured cost of acquiring it, which is shown to equal, the price or the wage rate on the market adjusted for a change in the efficiency of working time mediated through health enhancement and/or an increase in the productive efficiency of working hours due to knowledge and technology acquisition. Because our model includes utility arising from status-orientation in multiple dimensions, and because the extent and the range of such utility are socio-cultural-regime-specific while also being shaped by the household-specific receptivity and orientation to this regime, our model can potentially explain a diverse range of choice behavior some of which appear anomalous or even counter-intuitive to the rationality principle in the traditional sense. This added explanatory power helps close a gap between economics and other social sciences.

1. Introduction

For the economy as a whole, the economic agency is analyzed in two separate dimensions: one in consumption by households and the other in production/investment by firms. This convention does not apply to households engaged in both consumption and production/investment (Becker, 1962, 1965; Stigler and Becker, 1977). Such households are thought to transform market-purchased goods into utility-yielding commodities through production functions of their own. A similar treatment was also suggested by Lancaster, who viewed households as agents of activities who produce, from the goods purchased on the market, the desired utility-yielding objects called characteristics. Besides such production, households are engaged in a wide range of investment activities that are aimed at building human capital in various forms, e.g., knowledge/skills through education/training and health through health-enhancing activities, knowing that such capital expands the production possibility frontier of such material means as contribute to their well-being over time. While these dual aspects of the household agency are well recognized and analyzed for specific cases (e.g., Becker, 1962, 1965; Grossman, 1972; Stigler and Becker, 1977), the traditional model of household behavior still remains largely confined to the idea of utility maximization over the budget space of goods, which essentially amounts to a passive equilibrating response to market price signals. This idea, therefore, abstains from the notion of households as active producing agents with multiple motivations that relate to their conditions of existence as socio-economic and cultural beings.1 Here we pay attention to the fact that while economics in general assumes that all of the status variables and the underlying socio-cultural values, influential as they are, can be treated fixed, this assumption itself is based on a dubious presupposition because economic choices themselves, in the aggregate, affect what is assumed fixed to begin with.

Thus, we are back to the notion of economic agency in a value-laden environment in which households are actively engaged. This notion calls for an approach that views households as active agents who make integrated decisions of consumption-production-investment in multiple dimensions so as to maintain various statuses of import (such as knowledge/still, health, psychological stability, social reputation, political commitment, and religious identity) while getting utility from flow decisions as well as from statuses resulting therefrom. If households are viewed as such agents, we need, on top of an encompassing utility function, those functions that relate what households do in flow terms at any period to what they achieve in stock terms in the following period (i.e., to the attainment of the desired statuses), which we identify as the mediating functions in this paper. This need compiles another layer of difficulty to the task of problem-solving in general, that is, the difficulty of gathering and processing information in specifying such functions, which is further compounded by the fact the available time and the power of cognition is limited.2 A case in point is the attainment of health status, which is mediated by some sort of a health production function, which must be founded on medical and scientific knowledge, but it is not a simple matter even to approximate it from the vast pool of scientific information and data. Another case is seen in the task of knowledge and skill acquisition, which requires careful sorting and learning of which specific knowledge and skill is advantageous to achieving one’s goals. These examples are enough to point out that the household decision-making in pursuit of their multiple goals is not as simple as maximization of a utility function defined solely on the space of goods and leisure, only subject to a budget constraint facing them. Their behavior is, to be sure, knowledge-mediated and much more complex and involved than has been treated in the literature so far because the goal is to achieve the maximum utility from their activities that address both this knowledge-based mediation (i.e., investment) and what yields utility in the end.

To overcome this limitation, this paper proposes a generalized behavioral model, by taking note of the fact that the sources of utility are multi-dimensional, ranging from physical to social, psychological, and cultural wants, as well as by incorporating the point that utility is derived not only from flows of goods and leisure activities but also from those stocks that represent such important statuses as human capital, health condition, psychological stress, social reputation, political affiliation, religious identity, and so on. The disposition to anchor one’s position in the socio-cultural space by appealing to its symbolic values is a powerful and persistent drive behind household decisions. Since desired statuses can only be attained through the accumulation of flow choices over time, this view of households’ behavior calls for a series of reliable mediating functions that enable them to figure out which flow-choices will lead to the attainment of the desired statuses. Certainly, such functions need not be unique as there can be different ways of achieving the same objective. These functions basically share the same form as found in the functional relation that relates, in physical terms, the flows of investment to the amount of capital accumulated (i.e., the investment function). As mentioned above, the health status is attained in accordance with some sort of a health-production function founded on a set of scientific and medical knowledge that informs how healthy body and mind can be attained and maintained as well as what medical care is necessary in case of illness or mental distress.3 Likewise, a good work-life balance necessitates that stress (as part of mental health) be controlled in accordance with some kind of a stress-control function, which again must be based on scientific and psychiatric knowledge, although measuring stress itself may be problematic.4 But, the current psychology and neuroscience have identified what causes stress and how stress disturbs hormonal balance, thereby causing illnesses of various kinds, and this knowledge is essential in controlling stress and rectify those stress-causing conditions in working places. It is this knowledge that underlies a stress-control function we are dealing with here. Similarly, the motive for upper status identification in society — a strong motive particularly in an invidious culture — drives us to seek after such objects as are in line with our knowledge about the status ranks of the reference groups to be emulated or avoided (Veblen, 1899; Adam Smith, 1759; Hayakawa, 2000, 2010, 2017a; Hayakawa and Venieris, 1977).5 Furthermore, successful emulation and avoidance of relevant reference groups require factual knowledge of the lifestyles of these groups (where the lifestyles can be viewed as consumption technologies) as well as the actual data informing which goods possess positive or negative symbolic values of the lifestyles to be emulated or avoided. In a similar vein, households may go after the symbolic image of being pro-environmental in their behavior (as found in the behavior of SDG-conscious consumers or environmentalists) in much the same way as firms seek after the image of being environment-friendly as part of their social responsibility. Such image can only be realized through continuous pro-environmental choices made in consumption or production. Similar considerations extend to the case of religious and political identity as well. Religious identity requires regular church attendance and giving, which can be represented by some mediating function that connects the flow of attendance at church services to the capital of religious identity or firmness of affiliation, which depreciates with the neglect of this attendance. This relation may not be exact or perfect, but some relation hinting the connection must be mediating. Similar things can be said about political identity, which may call for a significant amount of time and pecuniary donation to the cause of political governance. There are many policy-conscious individuals who are willing to spend a significant amount of their time for political causes. As the success and the durability of democracy hinges on the presence of such individuals, political identity as a stock and political activities as flows cannot be ignored in a civil society. All of these considerations enter the deliberation of households in their decisions on how to allocate the resources at their disposal. This view of households as economic-social-cultural-political-religious agents who seek to optimize the overall well-being in a civil society has, in fact, formed the core of the tradition of ethics in Western Civilization, that dates back to time immemorial, or at least to Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Stoics, who addressed the importance of virtuous living in a civil society. Aristotle, in particular, spoke of the all-overseeing virtue of phronesis as a guiding principle of the life of socio-political beings.6 In our model-building, we try not to lose sight of how critical a role information plays in determining the mediating functions as an instrument of status attainment in various dimensions of life; these functions are themselves the results of careful deliberation and choice from the pool of many alternatives. Our view of human behavior thus reflects the fact that humans are beings with multiple orientations as they are aware that their living is embedded in the bio-physical, socio-cultural, and politico-religious environment and that we cannot escape the conditions of this environment as our so-called habitus.

With this expanded view of household behavior, we go beyond the conventional theory à la Hicks (1939) and Samuelson (1947) (see also Mas-Colell et al., 1995). Our theory also goes a step further than the consumption–production theory of household behavior pioneered by Becker (1965) in his time allocation model and by Stigler and Becker (1977) in their stable preference model, in both of which households are treated as producers of utility-yielding commodities in accordance with appropriate production functions.

We now turn to the task of model building. In our analysis, the time endowment is allocated to working hours and various distinct leisure activities. We abstain, in this paper, from the fact that consumption activities themselves are time-consuming; but this abstention is only for the sake of avoiding excessive complications. We will show that the implications of this fact are clear by extension. Also, the role of human capital (in the form of knowledge and skill) and investment in this capital will be discussed along the way although it is analogous, in treatment and implication, to health capital except that it directly affects the productivity of working time. We know that the acquisition of knowledge and skills to update the human capital has become extremely important for households if they are to keep their productive efficiency and their income-earning capacity from falling. All mediating functions are, in essence, production-investment functions by nature as they connect choice variables in flow terms to the stocks of statuses. Moreover, all mediating functions are based on knowledge, scientific/technological or socio-cultural. This knowledge, particularly the scientific and technological one, changes fast and hence must be updated constantly. We emphasize that this updating, together with information search, must be done on a continual basis to keep the productivity of the working time viable, which is essential for the protection of the income-earning capacity. Moreover, voluntary choices made in the context of the socio-cultural-political-religious regime gradually changes this context itself. Hence, the progress of knowledge and technology and the plastic nature of the socio-cultural structure makes agents’ choices evolutionary in nature. Economics, since inspired by Veblen (1898), has caught up with this idea, but the theoretical foundation of choice theory still remains devoid of a theoretical underpinning that links choice-making to the evolving nature of the decision-making environment.

Before we start our analysis, we think it is useful to point out a few things: First, what is problematic with the postulation of the utility function in the conventional way is that it neglects how it relates to the conditions of our existence and that the space on which the function is defined is too narrow to accommodate a wide range of concerns and orientations that occupy the mind of households along with the fact that the dynamic effects of choices they make in flow terms on the stock variables (the statuses) they value are ignored altogether because of this narrow definition. Our analysis can, therefore, be thought of as an attempt to demonstrate the still hidden power of the notion of the utility function that has remained largely untapped so far. Second, in this paper, we point out that the criticism accusing economics for claiming to be value-independent while acknowledging that sociology deals with the formation of normative value patterns in a social system, could be misleading because the utility function, viewed as a valuation function, is instrumental in making different values arising from the social-cultural-political-religious space commensurate after all as well as in sustaining such values through the act of decision making that this valuation makes possible. Third, the criticism voiced against the fact that economics assumes, unrealistically, full and perfect knowledge required to make rational choices is equally questionable because it is precisely under the imperfect conditions of evolving scientific and socio-cultural knowledge that economic choices are made with due attention paid to the cost of using wrong information in making choices over time. Such evolving conditions make household choices and, ipso facto, economic systems as a whole evolutionary in nature. The adherents of economics as an evolutionary science advocate this point by noting that economic choices made under the evolving conditions of existence are themselves evolutionary by the underlying logic that economic choices are rooted in the motivation that is oriented to the socio-cultural conditions of existence. Our paper supports this logic by addressing how choices made by households change with the evolving conditions of existence including scientific and technological information and socio-cultural institutions.

A word of caution is in order. A specific model analyzed here considers the relations that connect the current flow decisions on goods and leisure activities to the stocks of the statuses attained thereby as mediating functions. Yet, such mediating functions may in fact be activity-mediated themselves since specific activities (involving certain goods and time) are required to achieve the targets during the process of mediation. While such activities are not made explicit in our model but discussed, they can be thought of as being subsumed here in reduced form because uses of time are distinguished by their specific purposes. Hence the basic message of this paper remains intact although exact feedback loops may become more complex. Another point of caution is that although our analysis is static, the generalization to an intertemporal model can be done in a recursive manner by noting that the statuses obtained at the end of any period defines the beginning state of the period that follows as well as by incorporating the fact that the domain of the utility function is doubled because the arguments on which it is defined must span consecutive periods. Since such a generalization complicates notations without altering the basic message, we stay with the static framework here. One final point is that knowledge and skill acquisition has become an urgent task under the fast development of information/AI technologies, which threatens the survivability of many of the traditional occupations. This acquisition, however, takes up a significant amount of time for learning, which competes with other uses of time. But, if properly learned, the acquired knowledge advances the productivity of working time, hence affecting the income-earning capacity. This direct effect of knowledge and skill acquisition will be discussed in the text along with the health-mediated efficiency of working time.

2. A Generalized Utility Theory of Consumer Choice

Let an individual consumer/household have a utility function written as

Psychological stress S, on the other hand, is affected by working hours L, consumption of goods x=(x1,x2,…,xn), and leisure activities l=(l1,l2,…,lm). We assume that it increases with working hours while it can be controlled by consumption of proper goods and leisure activities.10 This mediating function, therefore, is written as

Social status, likewise, is determined by a similar mediating function written as

The consumer’s total time endowment is fixed at T. This endowment is divided into two categories of activities, working hours (L) and distinct leisure activities (l).11 Hence this constraint is specified as

We note that this utility function can be written in a reduced form, ˆU(x,l;𝒦). If 𝒦 were dropped from this form, it would be re-expressed as ˆU(x,l), which gives an impression that the utility function, if reduced all the way, can be treated after all as an entity independent of socio-cultural and psychological factors. This impression is out of line with the fact that there is no utility function that is independent of the socio-cultural context and the psychological make-up of the household as long as the utility function is intended to capture the socio-cultural want of the household. This reduced form informs that when the utility function is written as a function of x and l, it does not necessarily mean that it is independent of the household’s orientations about health, stress, and other factors; that is, it hides all sorts of factors that can each be treated as a function of x and l as shown by this implicit form.

We assume that the efficiency of labor is affected by health status. Hence, we let this efficiency of working hours be written as a function of H.

With (7) taken into account, equation (9) is written as

As mentioned above, the productivity of working hours is not only health-mediated but also mediated by the acquisition of the knowledge/technology of the time (Q above). If it is explicitly specified, Equation (9) will be specified as F(H,Q) where Q increases in accordance with its mediating function Q(x;l;𝒦). This opens up another route for increasing the efficiency of working hours, in which case the marginal productivity of goods and leisure activities on this efficiency will be composed of the knowledge effects as well as their health capital effects.

The market wage rate is given by W, so that the maximum wage earnings, if the total time endowment is devoted entirely to working, equal WTF(H). We call this the potential wealth, noting that this wealth, in our model, is determined endogenously because H is determined endogenously as will be shown below. The notion of potential wealth is similar to Becker’s (1965) notion of full income.

The potential wealth is allocated to n goods and m leisure activities, so that the budget constraint can be written as

With these specifications, the household’s optimization problem is written as

The household optimization problem :

The left side of (13) is the total marginal utility of good xi comprised of three components: Uxi is a direct marginal utility, UH(Hxi+HSSxi+Hℛℛxi) is an indirect marginal utility from three sources of utility: the first one from its direct impact on health, the second one from its indirect impact on health through psychological stress, and the third one from its indirect impact on health through social status standing. The right side is the effective price of good xi, i.e., its market price adjusted for a gain in income through its impact on heath, direct and indirect (i.e., through psychological stress and social status standing), which is translated into its utility-equivalent by the measure of the implicit marginal utility of wealth (the potential wealth) given by λ. A similar relationship holds for each leisure activity. The effective price of leisure li is the market price W adjusted for a gain in income through its direct impact on health as well as through its indirect impact on health mediated by psychological stress and social status standing, which is again translated into its utility-equivalent by the marginal utility of wealth λ. Note if knowledge/skill acquisition mentioned above, i.e., F(H,Q), is explicitly introduced, the right-hand side of equations (18) and (19) will be adjusted as

The notion of the effective price as a true measure of the cost of acquisition can explain why people are willing to buy more than the quantity justified by the direct utility or why people, in the opposite case, are only willing to buy less than the quantity justified by the direct utility. The former case arises when goods or leisure activities help gain health or other statuses that are conducive to productive life in general or when the productivity of time is enhanced directly through acquisition of proper knowledge and skill (in the case where F(H) is written as F(H,Q)), and the latter case occurs when the objects of choice get in the way of keeping this productivity high by its negative effect on health, or, more directly, when the accumulation of the knowledge and skill is hindered (in the case of F(H,Q)). Thus, what households perceive as the effective cost of acquisition (as a measure of the true sacrifice made in allocating scarce resources) can differ significantly from the market price.

To illustrate the meaning of these optimality conditions, consider the case of alcohol as an object of choice. The household derives utility from its consumption, direct and indirect: Indirect utility may arise from its impact on health which comes from three sources, one direct and the other two indirect through mediation of psychological stress and social status standing. A direct impact could be negative because alcohol can affect physical health negatively, but it could reduce stress, hence affecting mental health if it is consumed properly. Another indirect utility or disutility of alcohol may originate in its effect on the social-status position; that is, it could enhance or reduce social status standing through socializing activities intended to emulate the lifestyles of higher statuses (depending on the norms of consumption in reference groups). Hence, the household calculates the total marginal utility derived from all of these sources of utility and equates this composite marginal utility to the implicit utility value of the effective price of alcohol, which is the market price adjusted for positive or negative changes in income due to its impact on the efficiency of working hours through health. If consumption of alcohol, in net, increases the efficiency of working time, thereby contributing to income earning, the true (effective) price of alcohol is less than what the market price indicates, thereby resulting in more consumption of alcohol than otherwise. If the opposite is the case, there will be less consumption of alcohol than otherwise. What is important here is that the market price is only a raw signal, which must be adjusted to get a true measure of the opportunity cost incurred in the acquisition of the good. It is then this adjusted price that is equated to the composite marginal utility on the left side of the optimality condition.

Tobacco is another example. Under stressful working conditions, households may resort to smoking despite the health warning. This would be case if they thought that smoking mitigates stress and if this effect outweighs its negative effect. If the benefit exceeds the negative effect, the adjusted price of smoking is lower than the market price, which, when equated with the composite marginal utility, results in more smoking than otherwise. If, however, the adjusted price is higher than the market price, households will reduce smoking until its composite marginal utility matches this higher value.

Similarly, many individuals devote a significant amount of their time to exercising (e.g., working out at a gym, swimming, running, hiking, etc.) or the meditation practice. Clearly, the evaluation of these activities is based not only on their direct utility, but also on their benefits on health and mind. Furthermore, some of these activities may serve as an instrument of emulating the lifestyles of their reference groups, which may give rise to additional benefits on health. As different individuals have different needs, physical or mental, the composition of time allocation is individual-specific. This allocation is compounded by the fact that households need to allocate some of their time to the acquisition of new knowledge and skill in order to keep the productivity of their working time competitive enough to secure their income-earning capability. But the time they allocated to this acquisition of knowledge and skill (which is counted here as one of the leisure activities) competes with other leisure activities. So, individuals must come up with the best composition of leisure activities based on benefits on health and income earning. What is important here is that the true opportunity cost of time is not the same across leisure activities precisely because some are more conducive to health and income earning than others. More or less time will be allocated to leisure activities depending on whether the adjusted prices (the true opportunity costs) are lower or higher than the market wage rate. Thus, for goods or leisure activities alike, it is with good reason that households evaluate the effect of any object in their choice in its entirety (direct or indirect) in measuring its composite marginal utility and the true cost of acquiring it so as to bring about the best outcome in the utility that finalizes. Such calculation is rooted in the dual aspect of the household’s decision, consumption and investment, based on all-inclusive utility.

We note here that consumption may change over business cycles. For instance, consumption of tobacco may increase to alleviate stress caused by strenuous working that booms demand. This may partly be due to the fact that smoking provides an easier (less time consuming) means than other (more time consuming) stress-reducing activities (such as physical exercise), so that the cost of smoking inclusive of this time cost (measured by foregone income) is lower than the cost of other alternatives. When booms pass, stress returns to its normal level, and the need for smoking subsides. Whether smoking increases or decreases with business conditions is also affected by the presence of social sanctions for or against smoking. In a corporate culture today as well as in a more health-conscious society where smoking is prohibited in public places, smoking is regarded as a bad habit that shows, symbolically, either a lack of self-control or a lack of respect for other people, or both. If such sanctions are particularly strong, people may abstain from smoking even if they crave for it for the stress reason, and their health status may improve as a result. On the other hand, if such sanctions are weak enough, smoking may increase, causing health to deteriorate. Thus, how consumption of smoking varies over business cycles depend on the type of our cultural regime including social sanctions and the legal status of smoking.

We also note that in an invidious culture described by Veblen (1899) and Adam Smith (1759), consumer preferences are greatly influenced by institutionalized dispositions for higher status identification, and these dispositions are expressed through emulation of higher status reference groups and avoidance of lower ones. But successful emulation or avoidance requires factual knowledge and information about the lifestyles of these groups (viewed as consumption technologies), which are essential in determining the symbolic profits that goods or activities may carry for emulation. This implies that there cannot be any social emulation or avoidance pattern that is independent of any socio-cultural context and of any actual distribution of lifestyles in a social space, both of which are needed in imputing the symbolic values of those objects of choice under deliberation. In fact, symbolic values of a social object of choice are determined as a convolution of the emulation-avoidance pattern with the external conditions of the social status ranking of reference groups. This is why the above social standing function was written as ℛ(x,l;𝒦) where 𝒦 stands for the external conditions in which the desire for higher status identification is embedded. Once the structure of 𝒦 is specified, then an emulation-avoidance function similar to the one dealt with in Hayakawa (2000, 2017a), defined on the domain of the social status scale, can measure the capacity that any choice object (singularly or as a bundle) holds to satisfy the household’s social want for upper-status identification. Once this capacity is measured, the household will enter it in the utility function as a socio-economic source of utility. Such considerations elucidate why people of higher-status groups are willing to purchase exorbitantly expensive items. They may do so, not because they are subject to the so-called money illusion of some sort, nor because they measure the quality of these items by using their prices as a proxy index, but rather because they calculate socio-cultural symbolic profits of such items in emulating still higher status groups or in keeping themselves from being intruded by people of the lower ranks. If an object of choice is not fashionable in the upper-status groups to be emulated, they will be less attracted to it because of its lack of the required symbolic profits. This is a perfectly rational behavior of households embedded in a socio-cultural regime that features an invidious culture characterized by intricate codes of decorum and the socially appraised means of status identification. Once the social status is included in the utility calculus of households, their deliberation becomes socio-cultural-regime specific. Realizing this point is critical in bringing the deeply divided camps of economists and sociologists closer to a common field that avoids extreme stances of upward or downward causation.

The optimality conditions, (18) and (19), can also be expressed in terms of the equi-marginal principle. That is, the ratio of the total marginal utility to the effective price equals the marginal utility of the potential wealth λ, which essentially represents the total marginal utility per effective dollar spent on goods or leisure activities. It is this λ that connects all of the choices.

These conditions inform that those goods or leisure activities that have a higher composite marginal utility and/or a lower effective price will be consumed to a greater degree than otherwise, and that those having a lower composite marginal utility and/or a higher effective price will be consumed to a lesser degree than otherwise. If tobacco has a serious negative health effect that outweighs its positive stress-reducing effect, its effective price should be higher than the market price because of the fact that an induced loss of the efficiency of working houses (through deterioration of health) leads to a fall in income, which requires that the composite marginal utility increase just by a right margin so that the ratio is equalized to λ (which means that the quantity falls). The extent of this adjustment differs from one household to another because the utility valuation of smoking differs, but one thing is clear. The market price is not a true measure of the price that the household pays. On the other hand, if some goods are highly valuable for their health-enhancing and stress-reducing effects, their market prices over-estimate the true cost of acquisition because such effects bring about an increase in income earning, which must be deducted from their market prices to measure their effective prices. The quantities consumed of such goods need to be adjusted upward to bring the composite marginal utility per dollar of the effective cost of acquisition in line with the value of λ. Likewise, certain goods may enhance the consumer’s social status standing, and such effects could contribute to self-esteem, thereby giving rise to utility either directly or indirectly. An important point is that if health enters the deliberation of the household, the true cost of acquiring a good or engaging in a leisure activity must be adjusted accordingly because the efficiency of working hours is altered by a consequent change in the income earning capacity. This adjustment increases in scale with introduction of the direct effect of the acquisition of the technology of the time on the productive efficiency, hence on the income-earning capacity.

We note that the drive for upper-status identification is particularly strong in an invidious culture. In such a culture, this drive is likely to enter the utility calculus of households. On the other hand, in a non-invidious culture, such motives will be limited or even suppressed as one’s station of life remains more or less fixed. As mentioned above, the existence of this drive can account for the possibility that strongly emulation-oriented households may be willing to acquire certain goods even if their price are excessive. If this acquisition meets the symbolic purpose of emulation, the true cost of acquiring them is not as high as what their prices indicate. To make such drive even stronger, the possession of such symbolic goods may boost the sense of self-esteem and self-confidence, hence can have positive effects on health and, hence, on the efficiency of working and other activities. As often said, we toil to achieve a higher social status in order to get approbations (Adam Smith, 1759), and we want to demonstrate our success through possession of such expensive items as are favored or appraised by people of the higher classes (Veblen, 1899). When we see people paying excessive prices, we might ask whether their preferences are affected by prices themselves, possibly to the extent that they are subject to money illusion. This possibility was analyzed in a number of papers in the early stage of the development of the utility theory (e.g., Marschak, 1943; Scitovsky, 1945; Kalman, 1968; Allingham and Morishima, 1973; Dusansky and Kalman, 1974; Wichers, 1976; Hayakawa, 1976). Here we find it useful to trace the origin of such behavior to the expressive symbolism that accompanies upper status identification through the mediating function that connects flow choices to the social status attained thereby. This symbolism can account for the fact that even if the price is excessively high, the question is asked whether the good in question is worth the price when its symbolic values are considered. Most social emulation is symbolic in nature as expounded by Adam Smith in his The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), who took moral sentiments for approbations as the central theme in explaining the expansion of the economy. If this sentiment is strong and if the technology evolves fast, it is natural for households to consider both ends of deliberation: how much utility can be obtained and how much income can be secured, being fully aware that the two are inseparably connected. So, the symbolism is sought on the utility side as well as on the production side. These days, this is clearly demonstrated by the fact that we pay exorbitant fees for education/training, knowing that the knowledge and technology acquired will secure better jobs and pays as well as higher social status and better lifestyles afforded thereby.

Thus, we have come to the rationality principle. That is, while the sources of utility are many and complex, all of which enter the utility calculus of each household along with a number of mediating functions, its choice decisions on goods and leisure activities are dictated by the rationality principle that the composite marginal utility of each of these objects of choice is balanced with the true cost of acquiring it that incorporates its effect on health (direct or indirect) on the productive efficiency and the income-earning capacity as well as the more direct impact of the acquired knowledge and technology on this capacity.

Condition (22) gives the ratio of the sum of the composite marginal utility and the implicit utility value of an intended change in income earning, between any two goods, and condition (23) gives the ratio of the sum of the composite marginal utility and an intended change in income earning, between a good and a leisure activity. Likewise, condition (24) gives the ratio of the sum of the composite marginal utility and the implicit utility value of an intended change in income earning, between two leisure activities, which, in this case, equals one since all leisure activities face the same market wage rate. These conditions show that the ratios given on the left side equal the market price ratios (the raw market price ratios before adjustment is made for an intended change in the efficiency of working hours, hence in income earning). In the conventional utility theory, only the first term in the numerator and the denominator (that is, the direct marginal utility) on the left side are considered. In our generalized framework, however, the household evaluates all sources of utility and even the implicit utility value of an intended change in income that originates in direct and indirect health enhancement effects of goods or leisure activities that affect the efficiency of working time and income earning. We may call the ratios on the left side the generalized marginal rates of substitution. Again, with F(H,Q), the fifth terms in the numerator and the denominator in Equations (22), (23), and (24) are each adjusted by (18a) and (19a).

Conditions (18) and (19), or conditions (22), (23), and (24), show how important a role information plays in securing the required mediating functions. If households used wrong information in approximating a health-production function, for instance, the consequence would be serious. The same is true of using wrong information in pursuing upper-status identification, in which case purchases of expensive items may end up with a false symbolic meaning, thereby betraying upper-status identification. Likewise, if households wish to bestow their behavior with the image of being pro-environmental, it must be consistent with what science and technology informs on how it contributes to the environment. For all practical purposes of approximating the mediating functions in general, we need appropriate scientific or technological knowledge as well as accurate information on the data of the social facts including the lifestyle technologies, but all of this information is fluid and often fast-changing. This implies that households are forced to allocate some of their time to information gathering, processing, and evaluation. The optimality conditions we have identified above elucidate how wrong information or failure to upgrade information distorts households’ decisions by affecting Hxi, Sxi, ℛxi and Hli,Sli,ℛli, hence, the equi-marginal principle and the value of λ. The same is true with the acquisition of knowledge/skill to upgrade the efficiency of working hours, which are captured by Qxi and Qli; wrong skills fail to do the job.

We have termed λ the marginal utility of potential wealth. We demonstrate that this naming is warranted. In the calculus of maximizing the utility, the consumer determines the optimal quantities of goods and leisure activities. Suppose they are denoted by xD(p∗,W∗,WF(H∗)T) and lD(p∗,W∗,WF(H∗)T) (using vector notations: xD, lD, and p) where p∗,W∗,WF(H∗)T are, respectively, the effective prices of goods, the effective prices of leisure activities, and potential wealth at the market wage rate. We know that all of these indicators are endogenously determined. Hence, what follows is only an approximation holding in the neighborhood of the equilibrium point. With this limitation in mind, we proceed.

With these quantities, the household obtains utility V(p∗,W∗,WF(H∗)T) :

Taking the partial derivative of V with respect to WF(H∗)T gives

We next show that Shephard’s lemma and the Slutsky equation hold in our generalized framework, but the results must be interpreted carefully. Again, we proceed with a caution that the effective prices and wages are endogenously determined. Hence, the demonstration is only an approximation holding in the neighborhood of equilibrium.

For this purpose, we first consider the minimum expenditure function derived from the problem of minimizing the expenditure to attain a given level of utility, u :

Note that the prices p∗xi and the wage rate W∗i are the effective prices of goods and the effective prices of leisure activities, and that the optimality conditions (18) and (19) can be written as p∗xi=ˆUxi∕λ and W∗i=ˆUli∕λ.

The solution gives the compensated demand for goods and leisure activities.

Let these equations be written as

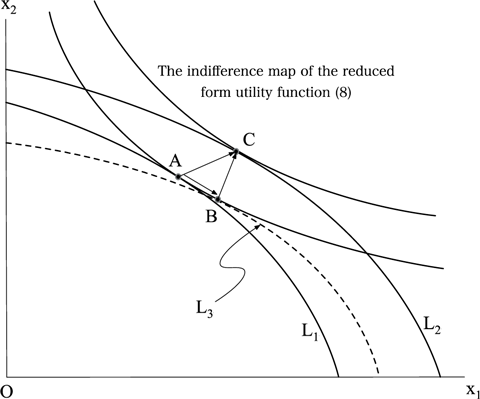

Figure 1 illustrates how the Slutsky equation holds between two goods, with careful interpretations and under the presumption that the effective prices, although endogenous, are treated given at their equilibrium values. The indifference map represents the reduced form ˆU(x,l) of the utility function specified in Equation (8). Because choices and the budget constraint are not dichotomous, it is not possible to draw a budget line in the usual way. Here the budget constraint curve is drawn as the budget frontier curve, with its shape being concave toward the origin. Under the originally given effective prices, this curve is drawn as L1, and the optimum choice is made at point A. If the effective price of x1 falls, the household faces a new budget frontier curve L2, and the optimum choice is then made at point C. The movement from point A to point C is the effective price effect; it is named “effective” as the household makes the optimum choice under the effective prices. This effective price effect is decomposed into two effects: the effective substitution effect and the effective income effect. Under the new effective price of x1, holding the utility at the same level as at point A, we get a bundle at point B along the budget possibility frontier curve L3, which is obtained under the lowered effective price of x1 accompanied by a virtual reduction in income amounting to the saving in acquiring the bundle at point A. The movement from point A to point B, therefore, is the effective substitution effect. An income equivalent of the utility difference between point B and point C is a virtual gain in income, which is also named “effective” as it is the gain that obtains when the optimal choices are made under the effective prices. A similar interpretation applies to Equation (45a). Thus, the Slutsky equation holds.

Figure 1. The Slutsky Equation

The effective price effect from point A to point C is decomposed into the effective substitution effect from point A to point B and the effective income effect from point B to point C. L1 and L2 are the budget frontier curves. L1 corresponds to the original effective price of x1, and L2 corresponds to the lowered effective price of x1 while the effective price of x2 remains fixed. L3 is a budget frontier curve that gives the same utility at point B as at point A under the lowered effective price of x1 accompanied by a virtual reduction in income amounting to the saving in acquiring the bundle at point A.

3. Conclusion

This paper proposed an integrated model of household behavior, in which utility is derived not only from flow choices of goods and leisure activities but also from the status in health, psychological stress, social reputation, political identity, religious affiliation, etc., and in which the status in each of these dimensions is attained in accordance with a respective mediating function that connects flow choices to the level of the status attained thereby. Since all of the functions are information-based, and because relevant information changes with the progress of science and technology as well as with the changes in social institutions and social facts, the choices made by households are evolutionary in nature.

This theory can account for a wide variation in household behavior partly because the relative strengths of the various effects in the flow-status relationships can vary across socio-cultural regimes and partly because how strongly households are oriented to the potential sources of utility can differ between individual households. Despite such variation, we have demonstrated that the equi-marginal principle, which is the hallmark of the traditional utility theory, holds. That is, the composite marginal utility of any flow choice, be it of a good or of a leisure activity, which is the sum total of the marginal utility from all sources of utility, direct or indirect, must be balanced with its effective cost which equals the prices and wages in the market adjusted for a gain or loss of income that the choice entails. This will be true even if goods are replaced by commodities as the final utility-yielding entities that are produced by households. Thus, despite the complexity of the utility calculus, the household’s deliberation in choice decision-making is guided by this rationality principle.

One of the reasons why certain behaviors might appear out of line with the normal range of behavior, hence, seem unamenable to the rationality principle is that the domain of the utility function could have been too narrowly defined to address a broad spectrum of interests and concerns that households have as status-conscious beings. Once it is acknowledged that households are such beings and that the relevant statuses affect not only utility but also the income-earning capacity through mediation of health and knowledge/skill, it becomes possible to analyze the household’s decisions as being based on maximization of an all-inclusive utility subject to all of the mediating functions that are instrumental in achieving the desired statuses. This expanded utility calculus renders extensive variations of household behavior “rationalizable”. In particular, if the all-inclusive utility includes the utility arising from the social status, the household’s deliberation channels the socio-cultural value norms at the macro level down to the voluntary choices made at the micro level. Our generalized theory, by explicitly considering this channel, opens the possibility that the idea of downward causation as advocated by sociologists in general can be integrated with the idea of upward causation that stresses voluntary decisions at the bottom. This integration of upward and downward causation helps elucidate the mechanism behind the evolutionary nature of socio-cultural norms and institutions as mediated by voluntary actions.

We close with a remark that while our generalized theory is only a first step in the direction of developing an all-inclusive decision-making theory of households as status-conscious beings who integrate consumption and investment, we hope this paper has demonstrated that such generalization is promising in analyzing choice decision-making in highly complex contextualized situations without losing sight of the rationality principle.

Acknowledgment

This paper grew out of the interest that I shared with Professor Euston Quah on the power of mathematics in economics as well as on the power of the methodology of the cost-benefit analysis. I appreciate the discussion we had when he presented his workshop of the cost-benefit analysis at Universiti Brunei Darussalam, which has helped me to sort out multi-dimensional sources of utility and reexamine the notion of cost along the line of the effective cost. I also thank him for having invited me to present a paper at The Multi-disciplinary Decision Science Symposium organized by Nanyang Technological University under his leadership in August 2010. Many of the ideas I presented at this symposium are included in this paper. I also would like to mention that at one of the past meetings of the Singapore Economic Review Conference, Professor Jack Knetsch, in a plenary session, shared his prediction with the audience that the heyday of behavioral economics would be coming. As an increasing number of research papers on the line of behavioral economics showed interesting examples that seemed to defy the conventional notion of economic rationality, I have turned my attention to investigating how behavioral economics can be reconciled with the principle of economic rationality. This paper is a partial answer to this question. In our private conversation, I asked him what his next prediction would be after behavioral economics. His answer was not definite. We miss Jack’s presence at the Singapore Economic Review Conference always with his read-to-share ideas.

Notes

1 Whether consumer behavior that appears inconsistent with stable preferences can be explained without abandoning such preferences is a matter of great importance to economic theory. Stigler and Becker (1977), in their paper De Gustibus Non-Est Disputandum, argued that this question can be answered positively if each household is viewed as a consumer-factory that produces utility-yielding commodities in accordance with relevant production functions with market purchased goods, time inputs, and human capital as inputs. Our approach to consumer behavior is similar to theirs in spirit as we consider households as active investors in health and other statuses through use of required mediating functions. The fundamental difference is seen in the fact that utility is derived not only from flows of goods or leisure activities but also from stocks that define the statuses of interest in multiple dimensions (economic, psychological, social, political, and religious) and that a mediating function is considered for each of these statuses.

2 Because this information-gathering and processing is increasingly facilitated by AI technologies these days, we may no longer have to resort to heuristic solutions in our problem solving. Also, the fact that the AI technologies can help us solve the problem of highly complex choices without spending much time and the fact that up-to-date science-based solutions are made readily available by such technologies at our fingertips are a great advantage to us. Such technology-reliant decision making may replace some of the problems analyzed by behavioral economics.

3 Recently, Hayakawa (2017b) gave an analysis of health-conscious consumer behavior, in which consumption is treated as an investment in health capital (called quasi-capital) in accordance with a health production function. It is an extended utility analysis that supplements Grossman's (1972; 2000) dynamic model of health as capital, or, more generally, the overall literature on health production; see Galama (2011) for a good survey of this literature. Whereas these models are mainly concerned with the question of how the demand for medical services is co-determined with the optimal stock of health capital over time, Hayakawa focused on health as the state that needs to be sustained on a daily basis by health-conscious consumption in accordance with scientific knowledge of health production, along with the idea that health affects the efficiency of labor, hence the income-earning capacity of the consumer in the market place. Be it a static or dynamic context, consumption is viewed as playing a dual role, both as a utility-yielding consumption and as an investment in health capital that affects future income and consumption. Under this dual role, Hayakawa explicated how the equi-marginal principle works across purchased goods as well as how the Slutsky equation and Shephard’s lemma hold. This approach is useful in analyzing health-conscious consumer behavior but cannot explain social status-conscious consumer behavior nor other status-conscious behavior. Hence, it is not general enough to explain the diversity of consumer behavior that reflects different kinds of status-orientation, but it is suggestive of a more generalized approach to take, that is, it suggests that consumer behavior be analyzed in terms of multiple sources of utility and in terms of flows and stocks that are linked by respective mediating functions. It is this approach that culminated in the present paper with its far-reaching implications.

4 Stress, as a response to abnormal pressures of various kinds for a prolonged period of time, causes physical, mental, and emotional problems that are accompanied by such harmful symptoms as headaches, insomnia, nausea, perspiration, indigestion, dizziness, high blood pressure, palpitations, etc. These symptoms are mediated/caused by the so-called stress hormones (adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol) and an imbalance in the function of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. While the causes of stress are many, in this paper we concentrate on working beyond a normal level as a potential source of stress, assuming that stress increases with strenuous working. We are aware that this is too simplistic a view, but at least it serves to show how stress may enter economic decision-making.

In this connection, it should be pointed out that there is a strain of literature that has brought the notion of psychological capital to the fore (e.g., Luthans et al., 2004; Luthans and Youssef, 2004). Psychological capital is a durable and inimitable disposition that prepares one in facing difficulty in challenging situations. It is thought to be composed of four elements: hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism. This tacit self-knowledge is regarded as a source of a long-term competitive advantage not only for organizations but also for individuals in managing their lives (Luthans, 2002a, 2002b). The idea builds on the principle of positive psychology pioneered by Martin Seligman (1991, 2002), who shifted the profession’s attention from the domain of mental illnesses/dysfunctions or disorder to a holistic domain of what constitutes human happiness and how this flourishing is enhanced by cultivating our own signature strengths and virtues. It is a modern version of Aristotle’s ethics. Under this view, stress becomes a complex internal response that is mediated by our internal strengths and virtues that are not fixed but malleable. This principle of positive psychology and the notion of psychological capital direct our attention to the need of a more holistic approach in understanding and improving the quality of life and management. Our theory in this paper shares a similar approach as we try to expand the domain on which utility is defined, so as to highlight the point that the motives behind our choices are complex and that rationalizable human behavior could be far more diverse than has been thought of.

5 There is a strain of literature that is related to the approach taken in this paper. Ruhm (2000) investigated, for the US economy, the relationship between economic conditions and the mortality on the one hand and the ten selected causal sources of fatalities on the other and found that this relationship is procyclical for eight of the sources. These findings, based on microdata, show that, in booms, smoking and obesity increase while physical activity falls along with less healthy diet. He attributed these results to four reasons: (1) The opportunity cost of time increases with economic upturns, thereby making physical activity and medical care relatively more expensive; (2) health, which is an input in the production of goods and services, is depleted faster than being replenished during booms; (3) while work-related accidents as well as drinking and driving are likely to rise in good times, other external sources of death need to be considered as well; (4) migration flows to booming areas, which are exposed to unexpected risk factors as well as to negative externalities. Similar findings were also made when Ruhm’s analysis was applied to a group of OECD countries where the strength of the relationship was shown to depend on the coverage of social insurance systems (Gerdtham and Ruhm, 2006). Moreover, Ruhm (2003), again using microdata, examined how health status and medical care utilization varied with state macroeconomic conditions, and found that there is a counter-cyclical variation in physical health (particularly pronounced for individuals of prime-working age, employed persons, and males). What is important in this study is that the negative health effects of economic expansions are larger for acute than chronic ailments and tend to persist or accumulate over time. On the other hand, Ruhm (2005), using another set of microdata, found that leisure-physical activity rises and smoking and excess weight decline during temporary economic downturns, highlighting the importance of the non-market time available for lifestyle investments and the behavioral changes that lead to improvement in mortality and morbidity. Furthermore, using individual-level data, Ruhm and Black (2002) looked into the relationship between macroeconomic conditions and drinking, and confirmed that procyclical variations were largely due to changes in consumption of existing drinkers. They suggest that any stress-induced increases in drinking in hard times are more than offset by declines that result from lower incomes. Ruhm and his colleagues’ findings on the procyclical mortality rates are supported by similar findings by Granados (2004), Ariizumi and Schirle (2012), Strumpf et al. (2017), and Van den Berg et al. (2017), but were challenged by counter-results in other studies (e.g., Economou et al., 2007; Halliday, 2006). And, some mixed results are reported by Ruhm (2013), Haaland and Telle (2015), and Sameem and Sylwester (2017). These studies are empirical in nature and could only allude to economic reasons behind the observed statistical relationships. Thus, the economic logic in this literature has remained largely in the dark, but our theory can explain these findings, confirmed or negated, by the relative strengths of the various effects that arise from multiple sources of utility and a health-production function.

More recently, Xu (2013), as an exception to the above strain of literature, specified the problem of household choice as an optimization problem subject to the budget constraint and the time constraint. The utility function is specified to depend on health, consumption of health-related goods, physical activity, and working hours. Health is produced in accordance with a health production function, which depends on health-related goods, physical activity, and working hours; working hours are added as an argument partly to capture the negative effect of the stress that working may cause and partly to capture the psychological effects of the same hours due, for instance, to the effect of depression on health. The budget constraint requires that the total expenditure on health-related goods, physical activity, and other consumption goods equal the wage earnings in the market, and the time constraint requires that working hours and time spent on health-related goods, physical activity, and other consumption goods equal the total time endowment. With these specifications, Xin examined empirically the effects of the variations in wages and working hours over business cycles on health-related behaviors (consumption of health-related goods and physical activity) of low-educated persons, looking at the relationship from the perspective of whether any activity, be it consumption or physical activity, is more time-consuming or less so. He found that leisure-time physical activity, binge drinking, and visits to physicians are time-consuming (making them relatively more expensive in terms of the market value of the time which rises with wages), hence countercyclical, whereas cigarette smoking is pro-cyclical as it is less time-consuming (making it relatively less expensive in terms of required time). The changes of local economic conditions, at the extensive margin of labor supply and employment, have the most important impacts on health behaviors. Although these findings are restricted to a group of less-educated individuals facing rationed working hours, at least, his study made an underlying causal mechanism explicit. Again, our theory can explain his empirical findings as well as what might have been otherwise, by focusing on the relative strengths of the possible effects of the arguments that enter the all-inclusive utility calculus.

6 The notion of homo economicus has been criticized by sociologists and other social scientists as too abstract and unrealistic to capture the actions of individuals embedded in a socio-cultural system. This is a legitimate criticism, but it is also true that the notion does not suggest in itself that individuals can disregard the conditions of human existence as socio-cultural beings altogether. In fact, the notion demands a highly stringent attitude on the part of decision makers as they are expected to evaluate all the benefits arising from all possible sources and impute the costs incurred in all dimensions. Hence, it accords well with the virtue ethics that advocates the refinement of virtues, intellectual or moral, as a prerequisite to the project of living well as characterized by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics (1984). This implies that, rather than disregarding these criticisms, economists can respond to them by generalizing their theories so as to be able to analyze the behavior embedded in a socio-cultural system and show how the rationality principle comes through no matter how complicated or all-inclusive the decision making might be. Likewise, rather than assuming away the problem of information gathering and processing by saying that agents are in possession of required information, economists can incorporate this processing in the decision-making itself. This extended line of inquiry is more consistent with the notion of homo economicus than confining it to a narrow set of conditions that are unlikely to be met. As an alternative to the notion of homo economicus, it was suggested, from the standpoint of behavioral economics, that decision makers should be treated more realistically as homo sapiens (Thaler, 2000). But, to the extent the concerns and interests of homo sapiens are extensive and all-inclusive, this notion seems to create more problems than it solves. This paper follows an extended line of inquiry by expanding the domain of the deliberation of households as well as by extending the domain of the utility function to accommodate all possible sources of utility. In this connection we should point out that many of the complex problems facing individual decision makers (such as information processing, the lack of literacy required for this processing, and limited cognition) will be expedited by AI technologies. Particularly serious is the lack of literacy required to process scientific and technological information. Under this situation, it is wise for individual decision makers to resort to these technologies instead of relying on outdated heuristic solutions.

7 In this specification of the utility function, goods and leisure activities yield utility directly as well as indirectly as seen below. If it is commodities that yield utility as argued by Becker (1965), we need to specify a production function for each of these commodities, which takes goods and leisure activities as its inputs. That is, x in the utility function will be replaced by c(x,l), a vector of commodities that are produced by x and l. Such an extension, therefore, adds another list of production functions on top of the mediating functions considered in this paper, as well as another layer of pressure for the use of time. We will abstract these aspects in this paper, but the implications of this additional consideration can be analyzed with little difficulty.

Also, it is possible to formulate our theory as an intertemporal utility maximization subject to a wealth constraint. This extension allows the marginal utilities of all intertemporal choices to be related by the equi-marginal principle subject to the rate of time preference and the interest rates. It can be done straightforwardly when preferences are recursive a la Koopmans (1960) and Uzawa (1968).

8 Leisure activities cover all activities other than working. While we use the word leisure, its activities are numerous in kind, e.g., physical exercise, learning and reading, music appreciation, attending a house of prayers, political activity, and so on. Thus, a given endowment of time is allocated to an array of activities and working time.

9 For the time being, we abstract the problem of selecting the best scientific information on which H(x,l,S,ℛ) is based. We later discuss how selection of wrong information distorts choice of goods, services, and leisure activities.

10 Stress is not necessarily a bad thing since some stress is desirable for a productive life, but the stress from strenuous working is harmful. This complicates the shape of a stress control function. In this paper, we work with an assumption that stress increases with working under the presumption that the optimal choice of leisure activities and working hours takes place at a point where any further working hours can only increase stress at the expense of the health status.

11 As mentioned in footnote 6, time used in producing commodities (as direct utility-yielding objects) is abstracted in this paper. A more general formulation of our theory can accommodate this feature in a straightforward manner.