Gravitational wave astronomy and the expansion history of the universe

Abstract

The timeline of the expansion rate ultimately defines the interplay between high-energy physics, astrophysics and cosmology. The guiding theme of this topical review is provided by the scrutiny of the early history of the space–time curvature through the diffuse backgrounds of gravitational radiation that are sensitive to all the stages of the evolution of the plasma. Due to their broad spectrum (extending from the aHz region to the THz domain) they bridge the macroworld described by general relativity and the microworld of the fundamental constituents of matter. It is argued that during the next score year the analysis of the relic gravitons may infirm or confirm the current paradigm where a radiation plasma is assumed to dominate the whole post-inflationary epoch. The role of high frequency and ultra-high frequency signals between the MHz and the THz is emphasized in the perspective of quantum sensing. The multiparticle final state of the relic gravitons and its macroscopic quantumness is also discussed with particular attention to the interplay between the entanglement entropy and the maximal frequency of the spectrum.

Contents

| 1 | Introduction | 3 |

| 1.1.Ten years of gravitational wave astronomy | 3 | |

| 1.2.Gravitational waves in curved backgrounds | 3 | |

| 1.3.The expansion history | 4 | |

| 1.4.The relic gravitons and the expansion history | 6 | |

| 1.5.The layout of this paper | 7 | |

| 2 | The Timeline of the Expansion Rate: Facts and Tacit Assumptions | 8 |

| 2.1.What do we know about the early expansion history? | 9 | |

| 2.1.1.Particle horizon and causally disconnected regions | 9 | |

| 2.1.2.Event horizon | 10 | |

| 2.1.3.Total number of e-folds? | 11 | |

| 2.2.The early expansion rate | 13 | |

| 2.2.1.Conventional inflationary stages | 13 | |

| 2.2.2.The early expansion rate | 15 | |

| 2.2.3.Adiabatic and nonadiabatic solutions | 16 | |

| 2.2.4.The scale-dependence of the expansion rate | 17 | |

| 2.3.What do we know about the late expansion history? | 20 | |

| 2.3.1.A radiation-dominated universe? | 20 | |

| 2.3.2.An extra phase preceding big bang nucleosynthesis | 23 | |

| 2.3.3.Multiple stages preceding big bang nucleosynthesis | 26 | |

| 3 | The Relic Gravitons and the Expansion History | 29 |

| 3.1.Random backgrounds and quantum correlations | 30 | |

| 3.1.1.The energy density of random backgrounds | 31 | |

| 3.1.2.Homogeneity in space | 32 | |

| 3.1.3.Homogeneity in time (stationarity) | 33 | |

| 3.2.Random backgrounds and quantum mechanics | 34 | |

| 3.2.1.Quantum mechanics and nonstationary processes | 35 | |

| 3.2.2.The averaged multiplicity | 37 | |

| 3.2.3.Upper bound on the maximal frequency of the spectrum | 38 | |

| 3.3.The expansion history and the spectral energy density | 41 | |

| 3.3.1.The maximal frequencies | 41 | |

| 3.3.2.The intermediate frequencies | 42 | |

| 3.3.3.The slopes of the spectra | 43 | |

| 3.3.4.Spectral energy density, exit and reentry | 45 | |

| 3.3.5.Approximate forms of the averaged multiplicities and unitarity | 47 | |

| 4 | The Expansion History and the Low-frequency Gravitons | 49 |

| 4.1.General considerations | 49 | |

| 4.1.1.Enhancements and suppressions of the inflationary observables | 49 | |

| 4.1.2.The number of e-folds and the potential | 50 | |

| 4.1.3.Illustrative examples and physical considerations | 51 | |

| 4.2.The tensor to scalar ratio | 52 | |

| 4.2.1.The tensor to scalar ratio before reentry | 52 | |

| 4.2.2.The tensor to scalar ratio after reentry | 53 | |

| 4.2.3.Oscillating potentials | 54 | |

| 4.3.Consistency relations and inflationary observables | 56 | |

| 4.3.1.Scaling of the spectral indices with the number of e-folds | 56 | |

| 4.3.2.An illustrative example | 57 | |

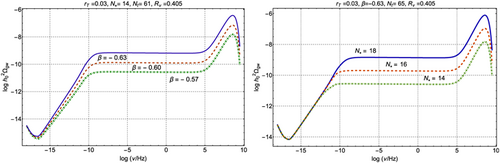

| 5 | The Expansion History and the Intermediate Frequencies | 59 |

| 5.1.The theoretical frequencies | 60 | |

| 5.1.1.Neutrino free-streaming | 60 | |

| 5.1.2.Big bang nucleosynthesis bound | 60 | |

| 5.1.3.The electroweak frequency | 61 | |

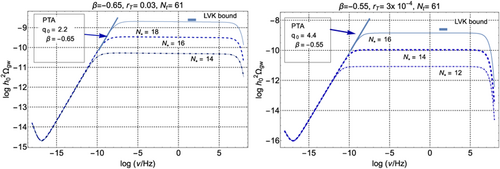

| 5.2.Pulsar timing arrays and the expansion history | 63 | |

| 5.2.1.Basic terminology and current evidences | 63 | |

| 5.2.2.The comoving horizon after inflation | 65 | |

| 5.2.3.The comoving horizon during inflation | 69 | |

| 5.3.Space-borne interferometers and the expansion history | 76 | |

| 5.3.1.The conventional wisdom | 76 | |

| 5.3.2.Chirp amplitudes and frequency dependence | 77 | |

| 5.3.3.Humps in the spectra from the modified expansion rate | 78 | |

| 5.3.4.Complementary considerations | 80 | |

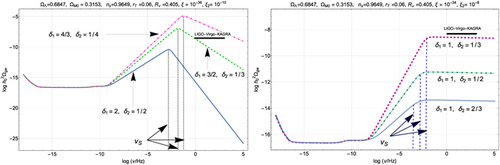

| 6 | The Expansion History and the High-Frequency Gravitons | 81 |

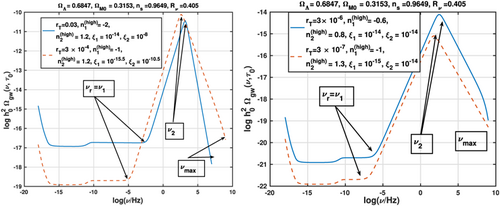

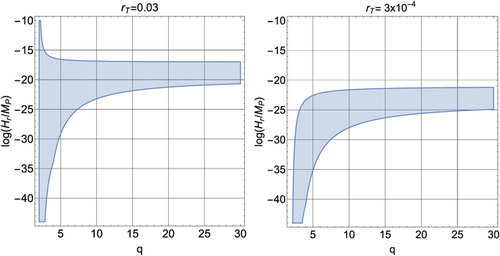

| 6.1.Spikes in the GHz domain | 81 | |

| 6.1.1.General considerations | 81 | |

| 6.1.2.Invisible gravitons in the aHz region | 84 | |

| 6.1.3.Bounds on the expansion rate | 86 | |

| 6.2.Spikes in the kHz domain | 88 | |

| 6.2.1.Maxima in the audio band | 88 | |

| 6.2.2.Again on the maximal frequency | 90 | |

| 6.3.Interplay between low-frequency and high-frequency constraints | 91 | |

| 6.3.1.General bounds on the inflationary potential | 91 | |

| 6.3.2.Quantum sensing and the relic gravitons | 92 | |

| 6.3.3.The quantumness of relic gravitons | 94 | |

| 6.3.4.The entanglement entropy | 96 | |

| 7 | Concluding Remarks | 100 |

| Appendix A. Complements on the Curvature Inhomogeneities | 103 | |

| A.1.General considerations | 103 | |

| A.2.The scalar power spectra | 105 | |

| A.3.The tensor to scalar ratio | 106 | |

| Appendix B. The Action and the Energy Density of the Relic Gravitons | 107 | |

| B.1.Generalities | 107 | |

| B.2.Second-order action in the Einstein frame | 110 | |

| B.3.Second-order action in the Jordan frame | 111 | |

| B.4.More general form of the effective action | 113 | |

| References | 114 |

1. Introduction

1.1. Ten years of gravitational wave astronomy

Gravitational waves have been predicted by Einstein in 19161 as a direct consequence of general relativity.2 Later on this problem has been revisited by Einstein and Rosen with somehow contradicting conclusions3 suggesting that gravitational waves could be unphysical. While the legacy of Ref. 3 brought eventually some late skepticism on the true physical nature of gravitational radiation (see, for instance, Ref. 4) the gauge-invariant nature of gravitational waves has been well established in the 1970s.5 In spite of the pioneering attempts of Weber6,7 and of the subsequent resonant detectors of gravitational radiation in the early 1970s, the first direct evidence of gravitational radiation dates back to the early 1980s when the orbital decay of a binary neutron star system has been originally observed.8 Roughly speaking almost one century after the first speculations, the gravitational waves have been detected by the wide-band interferometers.9,10,11 The signals observed so far mainly come from astrophysical processes occurring at late time in the life of the Universe and they are the result of accelerated mass distributions with nonvanishing quadrupole moment. One of the most exciting directions is however related to the possible existence of diffuse backgrounds of gravitational radiation produced thanks to the early variation of the space–time curvature. This collection of random waves encodes a snapshot of the early expansion history of the Universe prior to the formation of light nuclei. The purpose of this topical review is to summarize what can be said on the early expansion history of the Universe from the analyses of the stochastic backgrounds of relic gravitational waves.

1.2. Gravitational waves in curved backgrounds

In the 1960s and 1970s it was believed that the tensor modes of the geometry could not be excited in curved background geometries. Although the chain of arguments leading to such a conjecture would be per se interesting, this misleading perspective implied that both electromagnetic and gravitational waves could be considered invariant for a Weyl rescaling of the four-dimensional background geometry; from a practical viewpoint Weyl invariance implies that both electromagnetic and gravitational waves should obey the same equations in a Minkowski background and in curved geometries eventually obtained by Weyl rescaling from a flat space–time.12,13 This viewpoint persisted until the mid 1970s when it was challenged by a series of papers14,15 suggesting that gravitational waves can be indeed excited in curved backgrounds and, more specifically, in Friedmann–Robertson–Walker (FRW) cosmologies.16,17

Almost 50 years after these pioneering analyses the relic signals represent today a well-defined (and probably unique) candidate source for typical frequencies exceeding the kHz region where wide-band detectors are currently operating. Following the formulation of the inflationary scenarios18,19,20,21 it became gradually clear that the conventional lore would predict a minute spectral energy density in the MHz region.22,23,24 This is ultimately the reason why the most stringent tests of the conventional lore could come, in the near future, from the largest scales25 where the limits on the tensor to scalar ratio rT are in fact direct probes of the spectral energy density in the aHz region. Throughout the discussions of this paper the standard prefixes of the international system of units are systematically employed; so for instance 1kHz=103Hz, 1aHz=10−18Hz and similarly for all the other relevant frequency domains mentioned hereunder.

1.3. The expansion history

During the last 30 years cosmology astrophysics and particle physics experienced a progressive unification toward two complementary paradigms accounting for the observations at small and large distance scales. The Standard Model of particle interactions describes the strong and electroweak physics or, as we could say for short, the microworld; although there are various hints on its possible incompleteness (typically related to the existence of dark matter), so far the Standard Model has not been falsified. The so-called concordance paradigm (based on general relativity) is customarily employed to analyze the macroworld of cosmological and astrophysical observations involving, in particular, the data associated with the temperature and polarization anisotropies of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the large-scale structure data and the supernova observations. The concordance paradigm is sometimes dubbed ΛCDM where Λ accounts for the dark energy component and CDM stands for the cold dark matter. It is fair to say that, at the moment, the Standard Model of particle interactions and the ΛCDM scenario seem mutually consistent but conceptually incomplete.

In the concordance paradigm the source of large-scale inhomogeneities is represented by the adiabatic and Gaussian fluctuations produced during a stage of conventional inflationary expansion. The subsequent evolutionary history of the plasma assumes a long period of expansion dominated by radiation until the epoch of matter–radiation equality and this timeline is broadly compatible with the idea that all the particle species were in thermal equilibrium above typical temperatures of the order of 200GeV but there is no direct evidence either in favor of this hypothesis or against it. In the past the radiation dominance of the primeval plasma before big bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) has been taken as a general truism also because it was practically impossible to check directly the early timeline of the expansion rate by simply looking at electromagnetic effects. This was the viewpoint conveyed in the pioneering analyses of the hot big bang hypothesis formulated by Gamow et al.26,27,28 and subsequently confirmed with the discovery of the CMB29 by Penzias and Wilson also thanks to the neat theoretical interpretation formulated by Peebles.30,31 As we know the plasma became transparent to radiation around the time of photon decoupling. After that moment the slightly perturbed geodesics of the photons could be used to reconstruct the temperature and polarization anisotropies of the CMB32 but the electromagnetic signals coming from the earlier expansion history were quickly reabsorbed by the plasma and are today completely inaccessible to any direct detection.

The sensitivities of operating detectors33,34,35,36 are notoriously insufficient to measure the diffuse backgrounds of relic gravitons but in the future new detectors might cover different frequencies37 even beyond the so-called audio band ranging between few Hz and 10kHz. The gravitational waves produced thanks to the variation of the space–time curvature should then become an object of future empirical investigations even at high frequencies while at intermediate frequencies (in the nHz range) the backgrounds of relic gravitons could be observed by the pulsar timing arrays (PTAs)38,39,40,41 that are now primarily focused on the diffuse astrophysical signals. We actually know that every variation of the expansion rate produces shots of gravitons with given averaged multiplicities and specific statistical properties. If these spectra will ever be detected the timeline of the expansion rate might be directly tested without the need of postulating a particular post-inflationary paradigm before the curvature scale of BBN whose striking success is the last certain signature of radiation dominance for typical temperatures smaller than 𝒪(10)MeV. When considering these possibilities at face value there are at least two conceptually different issues that must be addressed.

| • | The first problem concerns the early expansion history of the current Hubble patch and its physical properties: Is the conventional timeline of the ΛCDM scenario really compelling or just plausible? | ||||

| • | The second class of questions involves the way relic gravitons could be used as a diagnostic of the early expansion history: How sensitive is the spectral energy density of the relic gravitons on the early expansion rates deviating from the ΛCDM timeline? | ||||

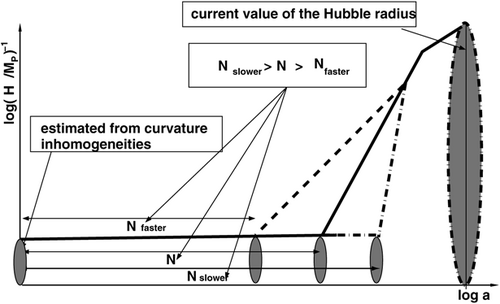

To address the first group of subjects we should first acknowledge that the causal structure of FRW models provides already a number of relevant constraints on the expansion history. However, even admitting that, at early times, the particle horizon should disappear or diverge (as it happens in the case of conventional inflationary scenarios) to be replaced by an event horizon, the subsequent evolution of the space–time curvature remains undetermined. To appreciate this relevant point we should actually observe that the total number of e-folds does depend on the post-inflationary rate of expansion. For instance when we say that 60 e-folds of accelerated expansion are necessary to suppress the spatial curvature we are actually referring to a post-inflationary evolution dominated by radiation. The same tacit assumption is systematically employed to confront the temperature and the polarization anisotropies of the CMB with the conventional inflationary scenarios.42,43,44

1.4. The relic gravitons and the expansion history

One of the purposes of this paper is to argue that the spectra of relic gravitons provide the only direct probe of the post-inflationary evolution prior to the formation of light nuclei. This is why a detailed analysis of such a signal is mandatory even in the absence of sensitive detectors that might be available only in the far future. Various secondary effects may produce different backgrounds of gravitational radiation during a fixed post-inflationary evolution like the one endorsed in the context of the ΛCDM scenario. These effects, however, always assume a specific knowledge that is still missing. Conversely the relic gravitons do represent the only conceivable direct diagnostic of the post-inflationary expansion history and this is the general perspective developed here. Since the spectrum of the relic gravitons extends from the aHz region up to the THz domain we can partition this broad frequency domain into three complementary ranges where different stages of the early expansion rate are correspondingly probed:

| • | the low-frequency region (between few aHz and the fHz) is directly sensitive to the expansion rate during inflation; in this region the upper limits on the tensor to scalar ratio deduced from the temperature and polarization anisotropies of the CMB are in fact bounds on the early expansion rate; the CMB can be in fact considered as the largest electromagnetic detector of long-wavelength gravitational waves; | ||||

| • | at intermediate frequencies various potential constraints are associated with the PTAs (typically operating in the nHz domain); from the viewpoint of the expansion history this region may set constraints both on the post-inflationary evolution and on the modifications introduced during the inflationary stage; | ||||

| • | finally in the high-frequency domain the constraints from the operating wide-band detectors between few Hz and 10kHz (as well as from other electromagnetic detectors operating in the MHz or GHz region) will be essential for the analysis of potential peaks in the spectrum of relic gravitons. | ||||

The first speculations suggesting that the relic gravitons could be used as a direct probe of the post-inflationary expansion history goes back to the late 1990s and this will be the general inspiration of this paper. In particular in Ref. 45 it has been suggested that different post-inflationary stages modify the slopes of the spectral energy density of the relic gravitons for frequencies larger than the mHz. It was found, quite surprisingly, that when the expansion rate is slower than radiation the spectral energy density exhibits a high-frequency spike.46,47 The original observation of Ref. 45 was that the post-inflationary evolution may be modified and this would be especially true if we have to accommodate a late-time dominance of the dark energy. In this case a post-inflationary evolution dominated by radiation would be less likely than a long stiff stage expanding slower than radiation.45 One of the first frameworks where these observations have been applied are the quintessential inflationary models.48 In this context the late-time dominance of dark energy occurs via a quintessence field that ultimately coincides with the inflaton. Later on different scenarios based on different premised have been proposed49 with the aim of accommodating an intermediate stage expanding at a rate different from radiation. For the purpose of this paper, however, we do not want to commit ourselves to a specific scenario or to a specific class of models. Indeed, as suggested in Ref. 45, the spectra of the relic gravitons chiefly depend on the evolution of the space–time curvature and not on the particular features involving the different sources.

1.5. The layout of this paper

The interplay between the timeline of the expansion rate and the spectra of the relic gravitons promises a direct connection between cosmology, quantum field theory and the effective description of gravitational interactions. On a more practical ground, in this topical investigation astrophysics and gravitational wave astronomy are seen as a tool for high-energy physics. In the past the common wisdom suggested instead that high-energy physics was probably the sole tool to infer properties of the primeval plasma prior to BBN. This conventional viewpoint did rest on the assumption that the post-inflationary expansion rate had to be fixed and almost perpetually dominated by radiation down to the scale of matter–radiation equality. In our context the timeline of the post-inflationary expansion rate is only a working hypothesis subjected to the direct tests associated with the diffuse backgrounds of gravitational radiation. Given the wealth of the connections between the various aspects of the problem it is impossible to analyze in detail all the relevant themes and this is why various collateral topics are swiftly mentioned but the interested readers may usefully consult a recently published book that dwells on the physics of the relic gravitons49 where most of the considerations omitted here are systematically addressed. The layout of this paper is, in short, the following. Before elaborating on the unknowns, Sec. 2 is focused on what it is understood about the early expansion history with the goal of distinguishing the facts from the tacit assumptions. Section 3 deals more directly with the interplay between the relic gravitons and the expansion history and since the various ranges of the spectra are directly sensitive to the evolutionary stages of the background geometry, it seems useful to examine separately the interplay between the relic gravitons and the expansion histories in the low (see Sec. 4), intermediate (see Sec. 5) and high frequency (see Sec. 6). In Sec. 4, we point out that the inflationary observables are either suppressed or enhanced depending upon the post-inflationary evolution that affects the total number of e-folds. In Sec. 5, we present a discussion on the mutual interplay between the modified expansion histories and the PTAs; toward the end of Sec. 5 we also argue that a the post-inflationary evolution may also produce signals between few μHz and the Hz where usually different sources are claimed to be relevant for the (futuristic) space-borne detectors. Finally in Sec. 6, we specifically address the direct bounds on the post-inflationary expansion rate coming from the high frequency and ultra-high frequency regions where absolute bounds on the maximal frequency of the spectra can be derived. Some ideas related to the use of quantum sensing for the detection of the relic gravitons will also be analyzed. The obtained limits on the maximal frequency are deeply rooted in the quantumness of the produced gravitons whose multiparticle final sates are macroscopic but always nonclassical. As the unitary evolution preserves their coherence, the quantumness of the gravitons can be associated with an entanglement entropy that is related with the loss of the complete information on the underlying quantum field. In the appendices we elaborated on some of the technical aspects that are often recalled in the main discussions. In particular, Appendix A illustrates a number of relevant complements on the evolution of curvature inhomogeneities that are specifically needed in the discussion while Appendix B treats the forms of the action of the relic gravitons in different frames.

2. The Timeline of the Expansion Rate: Facts and Tacit Assumptions

In the last 50 years the interplay between high-energy physics, astrophysics and cosmology has been guided by the tacit assumption that prior to matter–radiation equality the primeval plasma was always dominated by radiation50,51 and this general truism is also reflected in various cartoons that are customarily employed to represent the timeline of the expansion rate where different moments of the life of the Universe are illustrated with the supposed matter content of the plasma. This viewpoint has been also propounded by Weinberg in one of the first popular accounts of the subject.52 After the formulation of the inflationary paradigm in its different variants (see e.g. Refs. 18, 19, 20, 21) the hypothesis of a post-inflationary radiation dominance remained practically unmodified and even today it is customary to assume that after an explosive stage of reheating the Universe should become, almost suddenly, dominated by radiation (see, for instance, Refs. 53, 54, 55). Among the various conclusions that emanate from the assumption of an evolution dominated by radiation, the most notable one is probably that the plasma as a whole is described by a single temperature for most of its history. An equally relevant statement is that the inflationary expansion must (or should) last for at least 60 e-folds.53,54,55 Since this tacit assumption of radiation dominance is not directly tested (at least for temperatures larger than few MeV) more general possibilities will be discussed.

2.1. What do we know about the early expansion history?

2.1.1. Particle horizon and causally disconnected regions

A relevant constraint on the early expansion history comes from the causal structure of FRW models whose line element in its canonical form is given by

2.1.2. Event horizon

The previous discussion clarifies why the existence of the particle horizon leads necessarily to causally disconnected volumes; this occurrence clashes, among other things, with the high degree of homogeneity and isotropy of the Universe as it follows, for instance, from the analysis of the temperature and polarization anisotropies of the CMB. How come that regions emitting a highly homogeneous and isotropic CMB were causally disconnected in the past? To solve the causality problems of the conventional big bang scenario the idea is then to complement the standard decelerated stage of Eq. (2.6) with an epoch where the scale factor accelerates

2.1.3. Total number of e-folds?

If the accelerated stage of expansion is sufficiently long, all the scales that were inside H−1 at the onset of inflation are today comparable (or larger) than the Hubble radius. It is essential to appreciate that the quantitative meaning of the locution sufficiently long depends also on the post-inflationary evolution and not only on the inflationary dynamics itself. The duration of the accelerated stage of expansion is customarily parametrized in terms of the ratio between the scale factors at the end (i.e. af) and at the beginning (i.e. ai) of inflationc :

The number of e-folds required for the consistency of a given inflationary scenario does not only depend on the inflationary dynamics as it might seem to follow from Eqs. (2.13) and (2.14). In other words, while the physical features of the decelerated and of the accelerated expansions are per se relevant, what we want to stress here is that the indetermination of the post-inflationary evolution affects the specific value of the total number of e-folds. To clarify this point we consider the ratio between the intrinsic (spatial) and the extrinsic (Hubble) curvatures and recall that it is notoriously given by

Fig. 1. On the vertical axis the profile of H−1 is illustrated in Planck units as a function of the logarithm of the scale factor. In this cartoon (where, for the sake of simplicity, the slow-roll corrections have been neglected) the full thick line describes the standard inflationary evolution followed by a radiation-dominated stage. The dashed and dot-dashed curves correspond instead to a post-inflationary expansion rate that is either faster or slower than radiation, at least for some time before radiation dominance. In Subsec. 2.2, the early expansion rate is estimated from the large-scale curvature inhomogeneities whereas in Subsec. 2.3 we are going to present a series of quantitative estimates of N, Nslower and Nfaster.

2.2. The early expansion rate

2.2.1. Conventional inflationary stages

The expansion history during the inflationary stage follows from the equations connecting the Hubble rate to the corresponding sources. The single-field inflationary models can be notoriously analyzed in terms of the following scalar–tensor action (see, for instance, Ref. 55)

| • | if we presume, by fiat, that the post-inflationary evolution is fixed and known then the only sensible question and the sole concern should be somehow to reconstruct the functional dependence of the potential; | ||||

| • | conversely if post-inflationary evolution is unknown (or only partially known) it is less meaningful to aim at a reconstruction of the inflaton potential from the large-scale data since the number of e-folds ultimately depends on the post-inflationary evolution. | ||||

For different reasons both approaches are appealing but the former corresponds to the conventional lore while the latter perspective is pursued in this discussion: the ultimate goal would be to test the post-inflationary expansion rate rather than arbitrarily postulating a specific timeline. The post-inflationary evolution is not going to be fixed and this choice has a specific impact on the remaining part of the discussion. For this reason the properties of the expansion rate during inflation are technically more essential than the form of the potential although the obtained results can be related (at any step) to the more conventional approach. In the single-field case (and for the background geometry of Eqs. (2.1) and (2.2)) the evolution equations follow from Eq. (2.16) and they can be written as

2.2.2. The early expansion rate

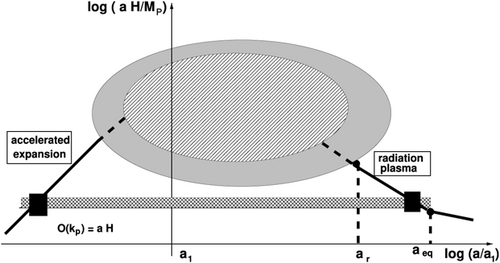

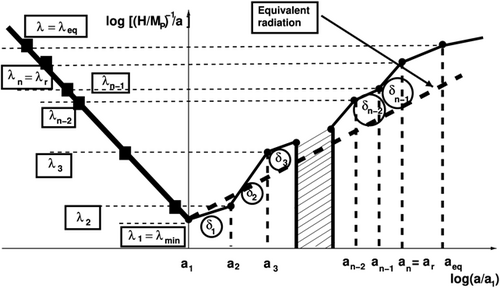

Although the post-inflationary expansion rate modifies the number of e-folds (and consequently all the inflationary observables), the early expansion rate can be estimated, at least approximately, without a detailed knowledge of the post-inflationary evolution. This happens since the early expansion rate ultimately follows from the analysis of the spectrum of curvature inhomogeneities associated with the CMB scales that left the Hubble radius during the first stages of inflation and reentered before matter radiation equality. Since the curvature inhomogeneities are conserved when they evolve for scales larger than the Hubble radius, the early expansion rate does not depend upon the total number of e-folds and the rationale for this statement is illustrated in Fig. 2 where the common logarithm of aH is reported as a function of the common logarithm of the scale factor. While during inflation aH∝a, in a radiation-dominated stage aH∝a−1; the two ellipses of Fig. 2 parametrize the unknowns of the intermediate evolution but a detailed knowledge of that regime is not strictly necessary to set initial conditions for the temperature and for the polarization anisotropies. The CMB observations involve in fact a bunch of wavenumbers k=𝒪(kp) where kp=0.002Mpc−1 is the conventional pivot scale that is used to normalize the large-scale power spectra. These typical scales are pictorially indicated in the lower part of Fig. 2 where the two filled squares denote the moment where k=𝒪(kp) gets of the order of aH. While the first crossing time occurs during inflation, the second one takes place prior to matter–radiation equality (see the right part of the cartoon). The scales k=𝒪(kp) become again of the order of aH when the Universe is already dominated by a radiation plasma (i.e. before matter–radiation equality) and their evolution is not affected by the unknowns of the post-inflationary evolution that may however modify the spectra at smaller scales; in this case the reentry of the fluctuations might not take place when the plasma is dominated by radiation.

Fig. 2. The common logarithm of aH is illustrated as a function of the common logarithm of the scale factor. The two ellipses account for the indetermination of the post-inflationary evolution that can have different durations depending on the differences in the timeline of the expansion rate. In the lower part of the cartoon the CMB scales k=𝒪(kp) approximately cross aH (see the two filled squares).

2.2.3. Adiabatic and nonadiabatic solutions

The argument of Fig. 2 holds only under the hypothesis that curvature inhomogeneities are conserved in the limit k<aH, i.e. for typical wavelengths larger than the Hubble radius. This is exactly what happens when the evolution of the curvature inhomogeneities on comoving orthogonal hypersurfaces (conventionally denoted by ℛ) is analyzed in the limit k<aH (or kτ<1). A complementary possibility is to employ ζ which measures the curvature inhomogeneities on the hypersurfaces where the density contrast is constant (see, for instance, Ref. 54 and references therein). Although ℛ and ζ are different variables, the Hamiltonian constraint associated with the relativistic fluctuations of the geometry stipulates that

2.2.4. The scale-dependence of the expansion rate

In the absence of nonadiabatic contributions the evolution of the curvature inhomogeneities obeys a source-free evolution equation that can be written in a decoupled form (see Appendix A and discussion therein); since the inflationary bound on the expansion rate follows from the large-scale evolution of , it is practical to recall the equation obeyed by the corresponding Fourier amplitudes :

2.3. What do we know about the late expansion history?

As already discussed after Eq. (2.13), the duration of inflation does depend on the post-inflationary evolution and this means that different expansion histories affect the number of e-folds required to bring all the physical scales of the model in causal contact. Different possibilities are examined hereunder with the purpose of quantifying the theoretical indetermination on the total number of e-folds.

2.3.1. A radiation-dominated universe?

One of the standard (unproven) assumptions both of the hot big bang model and of the conventional post-inflationary evolution is that the plasma must always be dominated by radiation even before the scale of BBN where the deviations from radiation dominance are severely constrained (see Sec. 4 and discussion therein). The gist of this argument is that, in the early hot and dense plasma, it is appropriate to assume an equation of state corresponding to a gas of relativistic particles; this choice is compatible with all the current data but it is neither compelling nor unique. A radiation-dominated stage of expansion extending between and the equality time is one of the assumptions customarily adopted for the timeline of the expansion rate in the context CDM paradigm. In terms of the cartoon of Fig. 2 we would then have that during inflation while in the radiation stage . This means, in practice, that the energy density of the background scales approximately as between the end of inflation and the equality time. The critical number of e-folds required to fit inside the current Hubble patch the redshifted value of (i.e. the approximate size of the event horizon at the onset of inflation) follows from the condition :

| • | the inflationary expansion rate is estimated from the amplitude of the scalar power spectrum and, more specifically, from Eq. (2.37); | ||||

| • | it is assumed that, in practice, there is no energy loss between the inflationary phase and the post-inflationary evolution (i.e. ); | ||||

| • | in the standard situation where and the value of is given by ; the contribution of to Eq. (2.45) is numerically not essential for the determination of . | ||||

The approximation is customarily enforced by CMB experiments when setting bounds, for instance, on the total number of e-folds42,43,44 and although energy is lost during reheating, in the case of single-field inflationary models this approximation is rather plausible since the combined action of the reheating and of the preheating dynamics leads to a process that is almost sudden.53,54,55 In this sense, if denotes the expansion rate during the last few e-folds of inflationary expansion, it is true that ; however, even for a difference of few orders of magnitude the quantitative arguments illustrated here will not be crucially affected. We recall that, conventionally, the reheating is the period where the entropy observed in the present Universe is produced and it typically takes place when all the large-scale inhomogeneities of observational interest are outside the horizon. The different approaches to the reheating dynamics are not expected to affect the large-scale power spectra.63

The number of inflationary e-folds introduced in Eqs. (2.13)–(2.15) depends on the post-inflationary evolution but it also scale-dependent. This happens because the actual observations always probe a typical scale so that this dependence also enters the number of e-folds and the expansion rate. In what follows and are associated, respectively, with the number of e-folds and with the expansion rate at the crossing of the CMB scales . Even though and H are conceptually different, since the curvature scale decreases very slowly during the inflationary stage. Most of the previous estimates can then be repeated in the case of . As in the case of , also is estimated in the present section for a post-inflationary thermal history dominated by a radiation background and this is why the overline is included; the values of are implicitly determined from

2.3.2. An extra phase preceding big bang nucleosynthesis

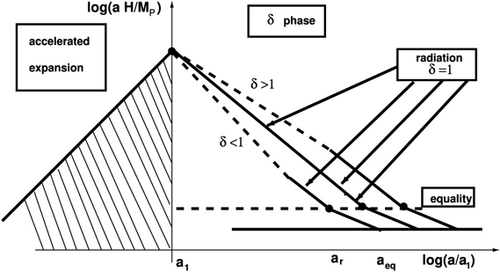

In the previous subsection, we considered a timeline dominated by radiation between the end of inflation and the equality epoch. We are now going to suppose that, prior to radiation dominance, the expansion rate is modified for a sufficiently long period where the expansion rate can be either faster or slower than radiation. Probably the simplest example along this perspective consists in adding a further stage of expansion between the end of inflation and the onset of the radiation-dominated phase. The ellipses of Fig. 2 are now replaced by the cartoon of Fig. 3 and the following comments are in order:

| • | as before during inflation we have that while in a radiation stage we would get : the simplest timeline is then the one illustrated with the full thick line; | ||||

| • | prior to the onset of the radiation stage and after inflation we have instead that where now parametrizes the expansion rate in the intermediate regime; | ||||

| • | if the expansion rate is faster than radiation; conversely when the expansion rate is slower than radiation (see, in this respect, the dashed timelines of Fig. 3). | ||||

Fig. 3. The conventional radiation-dominated epoch (taking place for ) is preceded by an intermediate phase parametrized by the value of . If we recover the case of a single post-inflationary radiation epoch. When the expansion rate is slower than radiation; conversely if the expansion rate is faster than radiation.

According to Fig. 3, the condition imposed by Eq. (2.39) becomes different and its modification depends on . Indeed, if the estimate of Eq. (2.39) is repeated, the value of gets shifted45,46,47 (see also Refs. 64 and 65)

| • | when the background expands faster than radiation (i.e. ) the value of gets smaller than in the case of radiation dominance (i.e. ); | ||||

| • | conversely when the expansion rate is slower than radiation (i.e. ) we have that . | ||||

The orders of magnitude involved in Eq. (2.50) are estimated by considering that the typical expansion scale of BBN is approximately whereas the inflationary expansion rate follows from Eq. (2.37) (i.e. ). This means that the relation between and is approximately given by

Let us now suppose, for instance, that . If the sources for the evolution of the geometry are parametrized in terms of perfect fluids with barotropic equation of state so that correspondsj to . In this case, from Eqs. (2.50) and (2.51), . In case the post-inflationary expansion rate between H and is instead slower than radiation so that we would have . Again, assuming the background is driven by perfect barotropic fluids, and it corresponds to a plasma where the sound speed and the speed of light coincide. Therefore for Eqs. (2.50) and (2.51) imply that . In summary the critical number of e-folds required to fit the redshifted event horizon inside the current value of the Hubble radius does depend on the post-inflationary expansion rate; thanks to the results of Eqs. (2.50) and (2.51) we can then estimate the theoretical error associated with the unknown post-inflationary expansion rate as

All in all, if the total number of e-folds is in the case of a radiation-dominated Universe, Eq. (2.52) suggests that the potential indetermination due to a modified expansion rate rangesk between 45 and 75. The same indetermination affecting also enters the value of . Indeed even in the presence of an intermediate stage preceding the conventional radiation-dominated epoch Eqs. (2.47) and (2.48) remain fully valid. The value of is relevant for various phenomenological aspects of the problem since it affects the inflationary observables that are specifically discussed later onl in Sec. 4. We finally recall that Eq. (2.36) has been correctly deduced in the case of radiation dominance (i.e. in the language of this subsection) and the same indetermination affecting the number of e-folds may also modify the value of the pivot scale in units of the inflationary expansion rate. In the presence of the -phase illustrated in Fig. 3 we have that Eq. (2.36) gets modified as

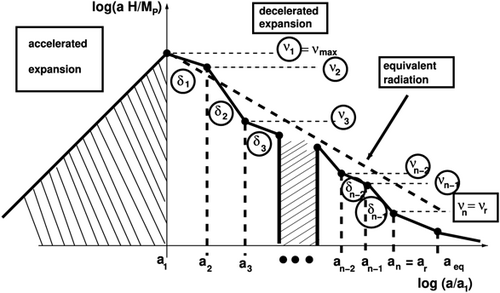

2.3.3. Multiple stages preceding big bang nucleosynthesis

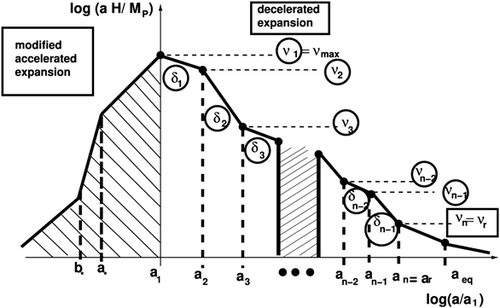

A natural extension of the results obtained in Eqs. (2.50)–(2.52) involves the presence of multiple post-inflationary stages parametrized by different values of the expansion rate conventionally denoted by with . It is actually plausible to generalize the previous considerations by replacing the single stage with n intermediate phases of expansion preceding the epoch of radiation dominance, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The cartoon of Fig. 3 is then substituted by the timeline of Fig. 4 where the initial stage of the post-inflationary evolution begins after the end of inflation (i.e. ) while the nth stage conventionally coincides with the standard radiation-dominated evolution i.e. and . As already explained before, we should always require implying that the BBN takes place when radiation is already dominant. During the ith stage of the sequence and the expression of given in Eq. (2.50) can be generalized to the timeline of Fig. 4 :

Fig. 4. As in the previous cartoons of this section, on the vertical axis the common logarithm of is reported as a function of the common logarithm of the scale factor. The region at the left corresponds, as usual, to the inflationary evolution while for the background is decelerated. It is also understood throughout the discussion that the post-inflationary epoch is bounded by the curvature scale of BBN so that . In this plot, we adopt the convention that and implying that the end of the sequence of intermediate stages coincides with the onset of the radiation-dominated evolution.

Fig. 5. As in the previous figure the common logarithm of the comoving expansion rate is illustrated as a function of the common logarithm of the scale factor. Prior to the onset of the standard inflationary stage of expansion the evolution is however modified.

In the previous cartoons of this section, we illustrated the effective rate of expansion in Planck units even though, in various cases, it is also useful to reason in terms of the inverse of . For this reason in Fig. 6 we now plot . Sometimes in the literature is referred to as the horizon or simply the Hubble radius. According to this terminology the different wavelengths of the gravitational waves and of the scalar modes of the geometry cross the Hubble radius at different times. The first crossing typically occurs during inflation (see the left part of Fig. 6); after the first crossing the wavelength gets larger than the Hubble radius. This moment is then referred to as the exit of the given wavelength. The second crossing (see the right part of Fig. 6) occurs in the decelerated stage of expansion and it is conventionally referred to as the reentry of the given wavelength since after this typical time the wavelength gets again smaller than the Hubble radius. The filled squares in Fig. 6 define the exit of a given (comoving) wavelength while the dots in the right portion of the plot denote reentry of the selected scale. According to Fig. 6, the wavelengths smaller than reenter before radiation dominance while the wavelengths reenter between the onset of radiation dominance and the epoch of matter–radiation equality. For the wavelength corresponds to comoving frequencies close to the maximal (i.e. ). The scales were still larger than the comoving horizon prior to matter–radiation equality and exited about e-folds before the end of inflation; the corresponding wavenumbers range therefore between and .

Fig. 6. We illustrate the inverse of the comoving expansion rate (i.e. the comoving Hubble radius) in the case of the timeline already introduced in Fig. 4. The terminology followed here is the one commonly employed in the literature. When a given wavelength crosses the comoving Hubble radius for the first time we say that it exits the horizon (see the filled squares). When the wavelengths crosses the comoving Hubble radius for the second time we say that it reenters the horizon. This is why in the text we indicated these moments as and , respectively. We stress however that, in this context, the terminology “horizon” is actually a misnomer since the evolution of the Hubble radius is just a way to illustrate the dynamics of large-scale inhomogeneities and has nothing to do with the causal structure of the underlying space–time.

3. The Relic Gravitons and the Expansion History

During the last 50 years a recurrent viewpoint has been that, ultimately, high-energy physics is a tool for cosmology and astrophysics. This argument rests on the observation that the plasma became transparent to electromagnetic radiation only rather late (i.e. after the last scattering of photons). Therefore there cannot be direct signals coming, for instance, from an expanding stage with a typical temperature of the order of few TeV. However, since these energy scales are reachable by colliders, particle physics is the only tool that we might have to scrutinize the early Universe. This perspective (implicitly assuming the dominance of radiation and the existence of a prolonged stage of local thermal equilibrium) should be probably revamped in the light of the direct detection of gravitational radiation. Indeed we do know that every variation of the space–time curvature produces shots of relic gravitons with given multiplicities and specific spectra.49 Since the sensitivities of gravitational wave detectors greatly improved in the last 30 years, it is plausible to assume that the direct observations might hit the thresholds of the cosmological signals during the next score year or so. Under this hypothesis the timeline of the expansion rate illustrated in the previous section may be one day testable in practice as it is already scrutinized in principle. Along this revamped perspective gravitational wave astronomy could become a tool for high-energy physics by conveying a more specific knowledge of energy scales that might not be accessible to colliders in the future.

The relic gravitational waves produced by the early variation of the space–time curvature14,15,16,17 lead to a late-time background of diffuse radiation. In the simplest situation the relic gravitons are produced in pairs of opposite three-momenta from the inflationary vacuum and this is why they appear as a collection of standing (random) waves which are the tensor analog of the so-called Sakharov oscillations71; this phenomenon has been also independently discussed in the classic paper of Peebles and Yu72 (see also Ref. 73). The late-time properties of the signal not only rest on the features of the inflationary vacuum but also on the post-inflationary evolution. It is well established that in the concordance paradigm the spectral energy density at late times is quasi-flat22,23,24 and it gets larger at smaller frequencies of the order of the aHz.25 This happens because, in the concordance scenario, the spectral energy density scales as between few aHz and 100aHz in the region where the current CMB observations are now setting stringent limits on the contribution of the relic gravitons to the temperature and polarization anisotropies.42,43,44 Along this perspective the low-frequency constraints translate into direct bounds on the tensor to scalar ratio and seem to suggest that at higher frequencies (i.e. in the audio band and beyond) the spectral energy density in critical units should be or even smaller. This result has been realized, at a different level of accuracy, in various papers starting from Refs. 22, 23, 24 (see also Refs. 74 and 75). The minuteness of the spectral energy density follows from the presumption that radiation dominates (almost) right after the end of inflation and it is otherwise invalid. As we argued in Sec. 2, the post-inflationary evolution prior to BBN is not probed by any direct observation and may deviate from the radiation-dominated timeline; if this is the case, the high-frequency spectrum of the relic gravitons can be much larger.45,46,47 In what follows, we are going to discuss first the statistical properties of the gravitons produced by the variation of the space–time curvature; in the second part of the section the discussion is focused on the slopes of the spectral energy density of the relic gravitons and on their connection with the expansion rate of the Universe.

3.1. Random backgrounds and quantum correlations

The random backgrounds associated with the relic gravitons are homogeneous but not stationary and this property is ultimately related with their quantum mechanical origin. Conversely the homogeneity of the background does not directly follow from the properties of the quantum mechanical correlations. In what follows, we shall try to clarify the analogies and the differences between these two aspects of the problem by swiftly summarizing the main conclusions of a recent analysis76 that follows previous attempts along similar directions.77

3.1.1. The energy density of random backgrounds

We start by considering a tensor random field and its Fourier transformn :

3.1.2. Homogeneity in space

The results of Eqs. (3.9) and (3.10) follow by considering the basic features of traceless and solenoidal tensor random fields supplemented by the notion of stochastic average introduced in Eqs. (3.4) and (3.5). A relevant result following from the previous considerations is that the two-point function of the tensor modes is homogeneous in space. By this we mean that the two-point function only depends on the distance between two spatial locations. If we compute the correlation functions of and of its derivative at equal times (but for two different spatial locations) we obtain

3.1.3. Homogeneity in time (stationarity)

It would now seem that the same kind of invariance should also hold when the spatial location is fixed but the time coordinates are shifted. In this case the two-point function of the tensor fluctuations would also be stationary, i.e. invariant under time translations. The stationarity is actually more restrictive than homogeneity if the random background is defined by Eqs. (3.1) and (3.4), (3.5). Indeed, as we are going to see, the stationarity ultimately restricts the time-dependence of the power spectra and . If we then avoid the complication of the spatial dependence and directly discuss a single tensor polarization , instead of an ensemble or random fields we deal an ensemble of real random functions . We then introduce the autocorrelation function defined in the context of the generalized harmonic analysis and associated with the finiteness of the integral80,81

3.2. Random backgrounds and quantum mechanics

For a quantum description of the relic gravitons the first step is to recall the second-order action for the tensor inhomogeneities deduced in Appendix B (see, in particular, Eq. (B.15)). The canonical momentum deduced from Eq. (B.15) is in fact given by and the resulting classical Hamiltonian is

3.2.1. Quantum mechanics and nonstationary processes

To analyze the stationarity of the process we need to introduce the autocorrelation functions depending on two different times and :

3.2.2. The averaged multiplicity

In a quantum mechanical perspective the amplification of the field amplitudes corresponds to the creation of gravitons either from the vacuum or from some other initial state. Since the production of particles of various spin in cosmological backgrounds is a unitary process12,13 (see also Refs. 89, 90,91) which is closely analog to the ones arising in the context of the quantum theory of parametric amplification,92,93,94,95,96,97,98 the relation between the creation and the annihilation operators in the asymptotic states is given by

3.2.3. Upper bound on the maximal frequency of the spectrum

Since we are here normalizing the scale factor as , the physical and the comoving frequencies coincide at the present time and from Eq. (3.44) the spectral energy density in critical units becomes

3.3. The expansion history and the spectral energy density

3.3.1. The maximal frequencies

While the bound on deduced in Eq. (3.51) follows from quantum mechanical considerations, in a classical perspective the maximal frequency is computed from the smallest wavelength that crosses the Hubble radius of 4 and immediately reenters; this is why Eq. (3.52) depends upon and also upon the timeline of the post-inflationary expansion rate discussed in Sec. 2. Let us therefore start from the simplest situation where the post-inflationary evolution is dominated by radiation. In terms of the cartoons of Figs. 4 and 6 this means that all the . Since in this case we already denoted the number of e-folds with an overline (e.g. , and do on) we are now going to indicate the maximal frequency deduced in this case by :

| • | in a model-dependent perspective the maximal frequency of the relic gravitons obeying the bound (3.51) is sensitive to the timeline of the post-inflationary expansion rate; | ||||

| • | in the case of a radiation-dominated evolution extending throughout the post-inflationary stage the maximal frequency is of the order of 300MHz; | ||||

| • | if the post-inflationary expansion rate is smaller than radiation for some time MHz; | ||||

| • | if the expansion rate is instead faster than radiation MHz; | ||||

| • | in general terms, recalling the considerations of Sec. 2, we have that . | ||||

Although the maximal frequency alone cannot be used to determine observationally the timeline of the expansion rate, Eqs. (3.53)–(3.55) suggest nonetheless that of the spectrum is sensitive to all the aspects of the post-inflationary evolution.u

3.3.2. The intermediate frequencies

From Figs. 4 and 6, we have that the bunch of frequencies corresponds to the wavelengths that left the horizon at the end of inflation and reentered immediately after. Depending on the timeline of the post-inflationary evolution there are other typical frequencies that can be explicitly computed. Moreover, since depends on , also all the other frequencies are sensitive to the specific value of the tensor-to-scalar-ratio. Rather than starting from the general considerations it is better to consider a specific example. Let us then suppose that, before the onset of radiation dominance, the post-inflationary epoch consists of thee separate phases. This means, according to Figs. 4 and 6, that the final spectrum is going to be characterized by the three typical frequencies , and . As already stressed after Eq. (2.55) we actually recall that we can always assume that and so that the nth stage of expansion corresponds (by construction) to the radiation phase. In the case the expression of follows from Eq. (3.55) and it is

3.3.3. The slopes of the spectra

In the previous subsection, we derived the typical frequencies of the spectrum in the case of a generic sequence of post-inflationary stages with expansion rates that can be either faster or slower than radiation. Within the same framework we could now discuss the slopes of within the various frequency domains. The calculation of the spectral energy density can be sometimes carried on in analytic terms but more often with appropriate numerical techniques. Here, we shall not review all these aspects but just remark that, for a sound estimate of the spectral slopes, it is sufficient to employ an approximate description that is based on the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) solution of the mode functions (see, for instance, Ref. 37 and discussion therein). If the power spectra and of Eq. (3.35) are inserted into Eq. (3.9) can be directly expressed in terms of the mode functions

3.3.4. Spectral energy density, exit and reentry

According to Eq. (3.69) the slopes of in a given range of wavenumbers chiefly depend on the dynamics of the expansion rate at and . For illustrative purposes we can consider that all the wavelengths of spectrum exited the Hubble radius during a conventional inflationary stage; this is the viewpoint of Figs. 4 and 6. The exit may also occur as in Fig. 5 but this possibility is going to be separately examined in Sec. 5. Since the exit of all wavelengths of the spectrum occurs during inflation,

3.3.5. Approximate forms of the averaged multiplicities and unitarity

In the past there have been various attempts to justify the loss of quantum coherence of the relic gravitons by claiming that when particles are copiously produced the averaged multiplicities are very large (see e.g. Ref. 133 and references therein). The averaged multiplicity accounting for the pairs of gravitons with opposite three-momenta for each tensor polarization follows then from Eqs. (3.41) and (3.42)

4. The Expansion History and the Low-Frequency Gravitons

4.1. General considerations

4.1.1. Enhancements and suppressions of the inflationary observables

The low-frequency range of the relic gravitons falls in the aHz domain and it corresponds to the CMB wavelengths that left the Hubble radius e-folds before the end of inflation. As already mentioned in section 2, these wavelengths are where and is the pivot scale at which the spectra of the scalar and tensor modes of the geometry are normalized within the present conventions; note in fact that aHz. The timeline of the post-inflationary evolution directly affects the values of the tensor to scalar ratio and of the other inflationary observablesz through their dependence upon which can be substantially different from . For instance a stage expanding faster than radiation has been suggested in the past with the purpose of enhancing the values of (see, for instance, Refs. 134, 135, 136). Indeed, if the expansion rate is faster than radiation gets eventually smaller than the value it would have when the post-inflationary evolution is dominated by radiation (see Eq. (2.57) and discussion therein). But since the inflationary observables and the tensor to scalar ratio are all suppressed by different powers of , they might all experience a certain level of enhancement as long as the post-inflationary expansion rate is faster than radiationaa and this is why this possibility has been employed to account for the BICEP2 excess.137 Different mechanisms have been suggested for the same purpose like the violation of the consistency relations caused, for instance, by the quantum initial conditions in the case of a short inflationary stage.138,139 A post-inflationary stage expanding faster than radiation efficiently enhances the value of especially in the case of single-field scenarios with monomial potentials. We now know that the BICEP2 measurements were seriously affected by foreground contaminations so that, at the moment, the current bounds suggests 42,43,44; this also means that the observational evidence would suggest that is comparatively more suppressed than in the case . In this respect an even earlier suggestion45,46,47 (discussed well before the controversial BICEP2 observations137) implies that the values of the inflationary observables can be further reduced (rather than enhanced) thanks to a stage expanding more slowly than radiation107,108 (see also Refs. 64, 65); this is ultimately the punchline of the considerations of Sec. 2 (see in particular Eq. (2.57) and discussions therein). As pointed out in Ref. 70 a reduction of (such as the one suggested by current determinations42,43,44) implies that the spectral energy density of relic gravitons is enhanced for frequencies larger than the kHz. This conclusion is particularly interesting since two widely separated frequency domains (i.e. the aHz and the MHz regions) may eventually cooperate in the actual determination of the post-inflationary expansion history, as originally pointed out in Refs. 107 and 108.

4.1.2. The number of e-folds and the potential

When the pivot scales cross the comoving Hubble radius the values of the inflationary observables can be directly expressed as a function of for . For this purpose the values of the slow-roll parameters (and their dependence on ) must be evaluated not simply for the conventional post-inflationary evolution dominated by radiation but in the case of different expansion rates. The total number of e-folds elapsed since the crossing of the CMB wavelengths follows from Eq. (2.14) and it is given by

4.1.3. Illustrative examples and physical considerations

In the case of plateau-like potentials may be written as the ratio of two functions approximately scaling with the same power for ; for instance we can have

4.2. The tensor to scalar ratio

The amplitudes of the tensor and scalar power spectrum are related via which is, in general terms, both scale-dependent and time-dependent :

4.2.1. The tensor to scalar ratio before reentry

The initial conditions of the temperature and polarization anisotropies of the CMB are set prior to matter–radiation equality (i.e. ) when the relevant wavelengths are larger than the Hubble radius. This means that Eq. (4.13) should be evaluated for and ; as before and denote, respectively, the moments at which a given wavelength either exits or reenters the Hubble radius (see Fig. 6 and discussions therein). In this approximation Eqs. (4.11) and (4.12) can be independently solved :

4.2.2. The tensor to scalar ratio after reentry

The expression of the scalar and tensor mode functions after reentry can be directly obtained from the previous results of Eqs. (3.62), (3.63) and from the subsequent discussion. In particular, within the same approximation leading to Eqs. (3.67), (3.68), the evolution of the tensor mode functions is approximately given by

4.2.3. Oscillating potentials

If the background expands as simple power law is constant; similarly, if the reentry of the given wavelength takes place when the inflaton potential is still dominant (and oscillating) remains approximately constant. To analyze this situation we can first write in terms of the inflaton potential , i.e.

4.3. Consistency relations and inflationary observables

In this final subsection, we are going to analyze the dependence of the observables upon the post-inflationary timeline encoded in the value of . We first introduce the standard form of the slow-roll parameters

4.3.1. Scaling of the spectral indices with the number of e-folds

When the consistency relations are enforced the tensor to scalar ratio cannot be equally small for all the classes of inflationary potentials and while the monomials are clearly excluded, the plateau-like and the hill-top potentials may lead to that are comparatively smaller. In the case of Eq. (4.6) the explicit expressions of the slow-roll parameters follow from and are given by

4.3.2. An illustrative example

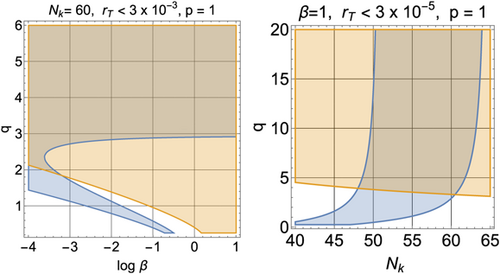

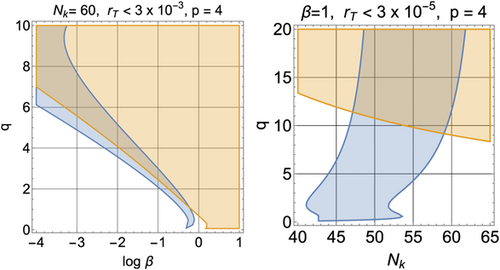

While the examples along these lines can be multiplied, for the present purposes, different functional forms of the potential do not radically modify the scaling of and of . From Eq. (4.42), and becomes

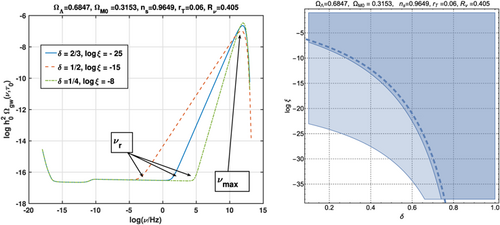

Fig. 7. We illustrate Eqs. (4.43)–(4.45) in the case . In the plot at the left we consider the plane while in the right plot we discuss the plane . In both plots there are two overlapping regions: the wider area corresponds to the condition while the narrower region illustrates the bounds on (see Eq. (4.34) and discussion thereafter). In the two plots we illustrated different values of .

Fig. 8. As in Fig. 7, we consider the example of Eqs. (4.43)–(4.45) but in the case . The same qualitative features already discussed in the case of Fig. 7 can be observed.

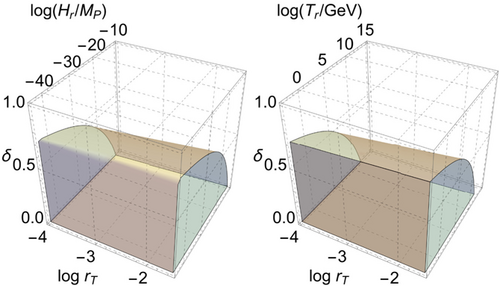

In summary we have that the low-frequency region is sensitive to the post-inflationary expansion rate through the number of e-folds which can be either larger or smaller than . If the timeline of the expansion rate is faster than radiation gets smaller and therefore all the inflationary observables are comparatively less suppressed than in the radiation-dominated case. Thanks to the current measurements42,43,44 we are however in the opposite situation and must comparatively larger than . In this case the inflationary observables are more suppressed than in the standard radiation-dominated case. Probably the most economical way of achieving this goal is to consider inflationary scenarios where the post-inflationary expansion rate is slower than radiation. In this case, following the considerations of Sec. 4, a high-frequency background of relic gravitons must be expected between the MHz and the THz.

5. The Expansion History and the Intermediate Frequencies

In the intermediate region of the spectrum (extending, approximately, between few pHz and the Hz) two important scales are related, respectively, to the BBN epoch (i.e. ) and to the electroweak time (i.e. ). While is three orders of magnitude smaller than the observational region of the pulsar timing arrays (PTA in what follows), is comparable with the window where space-borne interferometers might eventually operate a score year from now. During the last four years the PTA reported a series of evidences of gravitational radiation in the nHz range; it is then interesting to understand if these claimed signals are truly primordial or are just coming from diffuse backgrounds of gravitational radiation formed after matter–radiation equality. In any case the PTA set already an indirect constraint on the expansion history of the Universe. Within a similar perspective, the lack of detection between few Hz and the Hz (i.e. ) sets an essential limit on the post-inflationary expansion rate.

5.1. The theoretical frequencies

5.1.1. Neutrino free-streaming

Given the expansion rate at the BBN time (when the temperature of the plasma was approximately MeV), the general expression of is

5.1.2. Big bang nucleosynthesis bound

The frequency range associated with is related to a set of direct limits on the expansion rate of the plasma at the BBN epoch when the expansion rate was . Any excess in the energy density of the massless species at the BBN time increases the value of . The additional massless species may be either bosonic or fermionic; however they are theoretical traditionally parametrized in terms of the effective number of neutrino species as . The standard BBN results are in agreement with the observed abundances for .165,166,167,168 The most constraining bound for the intermediate and high-frequency branches of the relic graviton spectrum is represented by BBN as argued long ago by Schwartzman.102 The increase in the expansion rate affects, in particular, the synthesis of and to avoid its overproduction the expansion and rate the number of relativistic species must be bounded from above. All in all, if the additional species are relic gravitons102,103,104,105,106 the integral of the spectral energy density over the whole spectrum must satisfy the following bound :

5.1.3. The electroweak frequency

The Standard Model of particle interactions (based on the gauge group) appears to be successful at least up to energy scales and its basic correctness ultimately suggests that the electroweak phase transition cannot produce a detectable background of gravitational radiation for typical frequencies smaller than the Hz. To explain this viewpoint we start by remarking that the dynamics of the electroweak phase transition has been studied since the early 1970s and while it is plausible that spontaneously broken symmetries are restored at high-temperatures, the order of the electroweak phase transition determines the physical features of the purported gravitational signal. The symmetry breaking phase transitions may cause departures from local thermal equilibrium (and from homogeneity) but, according to the current experimental evidence, the electroweak phase transition does not lead to large anisotropic stresses that could eventually produce a diffuse background of gravitational radiation. A large anisotropic stress can only be produced if the electroweak phase transition is of first order and proceeds through the formation of bubbles of the new phase. It was clear already from the first (perturbative) estimates that the electroweak phase transition cannot be strongly first order169,170,171; however a definite conclusion on this issue was delayed because of the hope that, by using nonperturbative techniques,172 the essence of the perturbative result could be somehow disproved. The phase diagram of the electroweak theory at high-temperature has been first analyzed by reducing the theory from four to three dimensions and by subsequently simulating on the lattice the lower-dimensional theory with compactified time coordinate.173,174,175 These analyses have been later corroborated by genuine four-dimensional lattice simulations discussing the -Higgs system.176,177 The main results relevant for the present discussion can be summarized, in short, as follows. For approximate values of the Higgs mass smaller than the W-boson mass the phase diagram of the electroweak theory contains a line of first-order phase transitions but for GeV the phase transition if of higher order and when (as it is the case from an experimental viewpoint) the phase transition disappears since we can pass from the symmetric to the broken phase in continuous manner. In this cross-over regime there large deviations from homogeneity do not arise and diffuse backgrounds of gravitational radiation are absent.

Although the electroweak phase transition is of higher order, strongly first-order phase transitions may anyway lead to bursts of gravitational radiation and, for this reason, the production of gravitational waves has been investigated in a number of hypothetical first-order phase transitions. Provided the phase transition proceeds thanks to the collision of bubbles of the new phase, the lower frequency scale of the burst is (at most) comparable with the Hubble radius at the corresponding epoch. Denoting by the frequency of the purported burst, we should always require that where is the typical frequency corresponding to the electroweak horizon. This condition follows directly from the observation that gravitational waves should be formed inside the Hubble radius when the expansion rate of the Universe was approximately . Assuming the electroweak plasma is dominated by radiation between and the electroweak frequency is given by

5.2. Pulsar timing arrays and the expansion history

In the last few years a set of direct observations potentially related with the diffuse backgrounds of gravitational radiation have been reported for a typical benchmark frequency nHz. This range of frequencies is between 3 and 4 orders of magnitude larger than and it is currently probed by the Pulsar Timing Arrays (PTAs in what follows). As recently pointed out178 the signals possibly observed by the PTA may be the result of the pristine variation of the space–time curvature. The specific features of the current observations seem to suggest, however, that in the nHz domain may only depend on the evolution of the comoving horizon at late, intermediate and early times. This is also, in a nutshell, the systematic perspective swiftly outlined hereunder.

5.2.1. Basic terminology and current evidences

A PTA is just a series of millisecond pulsars that are monitored with a specific cadence that ultimately depends on the choices of the given experiment. We refer here, in particular, (i) to the NANOgrav collaboration,38,39 (ii) to the Parkes PTA (PPTA)40,41 and (iii) to the European PTA (EPTA).179,180 The PTA data have been also combined in the consortium named International PTA (IPTA).181 The data of the PTA collaborations have been released39,41,180 together with the first determinations of the Chinese PTA (CPTA).182 As suggested long ago the millisecond pulsars can be employed as effective detectors of random gravitational waves for a typical domain that corresponds to the inverse of the observation time during which the pulsar timing has been monitored.183,184,185 The signal coming from diffuse backgrounds of gravitational radiation, unlike other noises, should be correlated across the baselines. The effect depends on the angle between a pair of Earth-pulsars baselines and it is often dubbed by saying that the correlation signature of an isotropic and random gravitational wave background follows the so-called Hellings–Downs curve.185 If the gravitational waves are not characterized by stochastically distributed Fourier amplitudes the corresponding signal does not necessarily follow the Hellings–Downs correlation. In the past various upper limits on the spectral energy density of the relic gravitons in the nHz range have been obtained186,187,188,189 and during the last five years the PTA reported an evidence that could be attributed to isotropic backgrounds of gravitational radiation. The observational collaborations customarily assign the chirp amplitude at a reference frequency that corresponds to :

| • | The pivotal class of models analyzed in Refs. 38, 39, 40, 41, 179–182 always assume (i.e. ); recall, in this respect, that the relation between and is simply given by . | ||||

| • | In the former data releases the ranged between and depending on the values of .38,40,179,181 | ||||

| • | The latest data releases of the Parkes and the NANOgrav collaborations41,39,180 seem to suggest different origins of the diffuse background of gravitational radiation. | ||||

| • | In particular, after considering 30 ms pulsars spanning 18 years of observations, the PPTA collaboration estimates with a spectral index 41; for a spectral the pivotal model the collaboration suggests instead which is compatible with the determinations of the previous data releases40; the PPTA collaboration does not clearly claim the detection of the Hellings–Downs correlation41 and carefully considers possible issues related to time-dependence of the common noise. | ||||

| • | The conclusions of the PPTA seem significantly more conservative than the one of the NANOgrav collaboration examining 67ms pulsars in the last 15 years. | ||||

| • | The NANOgrav experiment claims the detection of the Hellings–Downs correlation39 but the inferred values of the spectral parameters are slightly different from the ones of PPTA since and .39 | ||||

5.2.2. The comoving horizon after inflation

The measurements of the PTA set a number of relevant constraints on the spectrum of the relic gravitons and on the expansion rate of the Universe. If the observed excess in the nHz range is just a consequence of the primeval variation of the space–time curvature the spectral energy density of the relic gravitons in the nHz domain only depends on the evolution of the comoving horizon at late, intermediate and early times.178 Two complementary aspects of the problem will now be addressed. In the first part of the discussion, we are going to see if a post-inflationary modification of the expansion rate can account for the nHz excess. In the second part of the analysis, we consider instead the possibility of explaining the observed PTA excess through the evolution of the effective horizon at early times.

A first general observation is that, in the concordance paradigm, the PTA results do not set any further constraint besides the ones of the aHz region already discussed in Sec. 4. This happens because the spectral energy density of Eqs. (5.15) and (5.14) always exceeds the the one of the concordance paradigm in the nHz region. Indeed, if the expansion rate is dominated by radiation after inflation, for typical frequencies larger than . Furthermore, in the concordance paradigm, is a monotonically decreasing function of the comoving frequency between the aHz and the MHz domain. This means that in the nHz range the signal of the relic gravitons produced within the conventional lore is always 10 orders of magnitude smaller than the one suggested by Eqs. (5.15) and (5.14). If the expansion history is modified in comparison with the concordance paradigm the relevant time-scale of the problem must coincide with , i.e. the moment at which the wavelength associated with crossed the comoving Hubble radius after the end of inflation (see Fig. 6). The actual value of represents in fact a fraction of the time-scale associated with BBN :

To substantiate the previous statement we now consider a generic post-inflationary expanding stage (i.e. a single -phase in the language of Sec. 2). When the wavelengths cross the comoving Hubble radius during the -phase we have

| • | in the low-frequency regime the slope is simply given by ; this is true when the consistency relations are enforced as we are assuming throughout; | ||||

| • | if the wavelength corresponding to reenters the Hubble radius when the high-frequency slope follows from Eqs. (3.75)–(3.77) and it is . | ||||

To compare with the potential excesses suggested by the PTA we may recall Eq. (5.13) and then consider the theoretical estimate of the spectral energy density in critical units65

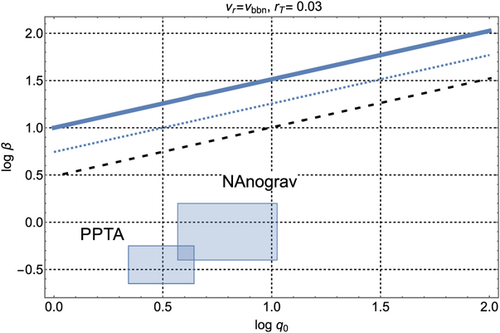

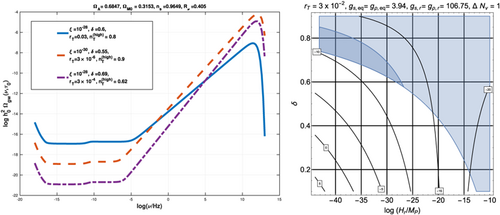

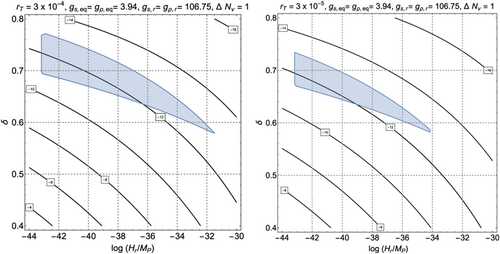

The result of Eq. (5.22) must then be compared in the plane with the ranges of and determined by the PTA collaborations. The two filled rectangles in Fig. 9 correspond to the observational ranges of and ; in the same plot the relation between and has been illustrated as it follows from Eq. (5.22) for two neighboring values of . The three diagonal lines of Fig. 9 imply that the values of required to obtain of the order of or should be much larger than the ones determined observationally and represented by the two shaded regions. Since the full and dashed lines of Fig. 9 do not overlap with the two rectangles in the lower part of the cartoon, we can conclude that the excess observed by the PTA collaborations cannot be explained by the modified post-inflationary evolution suggested of Fig. 9. For the specific case Eq. (5.21) becomes

Fig. 9. The three straight lines illustrate Eq. (5.22) for (full line), for (dotted line) and for (dashed line). The two filled rectangles define the regions probed by the PPTA and by NANOgrav in the plane . The two diagonal lines do not overlap with the shaded areas appearing in the lower portion of the plot and this means that the amplitudes and the slopes of the theoretical signal cannot be simultaneously matched with the corresponding observational determinations. Common logarithms are employed on the horizontal axis.

5.2.3. The comoving horizon during inflation