Disaster Risk Management and Resilience Assessment of Small Communities in Iran

Abstract

One of the main challenges facing rural areas in Iran is a lack of disaster risk management. This calls for a comprehensive framework for assessing resilience in small communities. This study seeks to establish such a framework based on the general principles of the Sendai Framework. So, an attempt is made to use a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to operationalize and score indicators and risk management components, and then choose one of the rural areas in northern Iran as a sample for the framework’s implementation. The results show that a resilience assessment on small communities should do two things: outline the resilience situation and create a platform for dialogue and mutual thinking. Residents should be able to talk about risk reduction continuously and purposefully and take small, purposeful steps in this direction. It seems that Iran’s centralized planning system is more flexible in entrusting affairs to small communities and is more likely to form active cooperative cores. For this reason, it can be seen that voluntary activities have played an essential role in providing social services during the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine period, and the volunteers themselves have also benefited from voluntary activities. As a result, volunteer groups have gained opportunities to promote local development and foster ownership and responsibility. However, there are concerns about the sustainability of these activities, which are related to the two issues of ensuring financial stability and providing volunteers in the long term.

1. Introduction

Disasters in the era of climate change strongly affect developing countries, and these effects are much greater in deprived regions, especially in rural areas with indigenous and disadvantaged populations that are exposed to severe inequality (Atkinson and Atkinson, 2023). For instance, disasters, many of which are exacerbated by environmental degradation and climate change in Iran and which are increasing in frequency and intensity, disproportionately affect rural areas and small towns more. They are serious obstacles to the sustainable development of such societies and account for a large share of total economic losses (Javadinejad et al., 2019; Mansouri Daneshvar et al., 2019), for example, floods hit the north and south of Iran in spring 2019, affecting most of Iran’s rural area and small towns. The floods caused a USD 3–5 billion economic loss to the country (Khankeh et al., 2020), together with heavy human and environmental losses. While flood preparedness through disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategies, including watershed management enhancements and flood control measures, can prevent much of this destruction. Reducing the risk of disasters not only saves human lives, but can also contribute to the development of individuals and societies. Economic resources, political will and a shared sense of hope form part of our collective protection against disasters. Strengthening preparedness, creating resilience and improving local capacities for risk response are a necessity. In addition, it is important to consider DRR as a continuous commitment in the context of various social, economic, governmental, and professional activities, rather than take it as an area that requires highly specialized services or technical know-how that focuses solely on security or emergency response issues. DRR is an integral part of development that involves all sectors of society, starting with those most exposed to foreseeable risks.

To be efficient and effective, disaster risk management (DRM) requires the implementation of a multi-hazard, multi-sectoral, inclusive, and accessible program, including economic, structural, legal, social, health, cultural, educational, environmental, technological, political, and institutional measures that reduce exposure and vulnerability to hazards and disasters, increase preparedness for response and recovery, and thus strengthen resilience (Agrawal, 2018; Urban and Nordensvärd, 2023).

In the past years, most of the researchers and policymakers in Iran have been concerned about the challenges and resilience of large cities (Barzaman et al., 2022; Moradpour et al., 2023; Nedaei et al., 2022), instead of small communities. Meanwhile, according to Farajisabokbar et al. (2021), about 71% of rural communities in Iran are highly exposed to risks and they are among the least developed regions of Iran. Climate changes, environmental crises, and major hazards such as floods, droughts, earthquake, and landslides have always been a threat to such small communities (Farajisabokbar et al., 2021). So, it is crucial to increase the resilience of these poor and underdeveloped communities, which have suffered the most damages from disasters endangering their lives and livelihoods. But until now, no one has considered an integrated framework for reducing risks in such communities. It is difficult to identify the resilience of small communities in Iran due to their diverse geographical features and the lack of reliable data and sufficient information. An integrated framework for their resilience is essential to mitigating the potential impacts of disasters, and can help improve their coping capacities and provide a more accurate picture of the necessary actions. The study aims to help greatly cut disaster risks and losses in small Iranian communities, which requires perseverance, more attention to people and their health and livelihoods, and regular follow-up. In view of the above, the authors seek to develop an integrated resilience framework following the UN Sendai Framework for DRR.

2. Literature Review

Disaster management approaches are multidisciplinary and applicable to social rather than natural systems, with a focus on governance for disaster mitigation and preparedness, engineering the built environment, and the social organization of communities. By emphasizing resilience and participation, the approaches prefer planning with a community to planning for it (Mayer, 2019; Thomas et al., 2019). Through participation in planning, communities think about their risks and develop measures and projects before a disaster can occur, making it easier to recover from future events (FEMA, 2013, 2023). Such resilience planning emphasizes the potential of stakeholders including individuals, communities, governments to adapt to uncertainties and changes through actions like DRR. It considers the social vulnerabilities that shape pre-disaster conditions and also looks at the unequal distribution of resources, access to information, and conflicts over power. Such planning tends to consider the potential for systemic changes that can address social inequalities in an effort to promote adaptation (Mayer, 2019).

In rural planning, resilience studies focus on capacity-building and empowerment, such as trust, community capacity, leadership, and connection to wider networks, including governments (Mackay and Petersen, 2015; McAreavey, 2022). Scott (2013) said resilience studies make sense when you understand the local context and place. He sees resilience as an alternative public policy for rural development and an analytical framework that considers the role of path and place dependencies. In rural studies, the inquiry by Adger (2000) is often known as the start of resilience thinking. He believed that social systems, like natural ones, can adapt to pressure and turmoil without changing their function and form. Adger’s resilience thinking can be considered from the perspective of social-ecological systems. Social-ecological system theorists see society as a complex and dynamic structure that consists of thousands of human-ecological subsystems. These subsystems interact and change in short- and long-term periods of growth, disintegration, reorganization, and revival (Adger and Hodbod, 2014). Current studies of social-ecological systems state that resilience not only involves an efficient return to normal, but is also the basis for social changes and revitalization. In such a view, the goal is not a simple adaptation, but to push the structures toward the threshold of meaningful changes. Disturbances in a system provide opportunities for positive changes and initiate cycles of adaptive renewal. This more complex view of resilience shifts the focus from controlling changes in stable communities to managing the capacity of dynamic communities that can cope with, adapt to and shape changes. In such a case, a clear distinction can be drawn between equilibrium and evolutionary resilience studies (Li et al., 2020; Scown et al., 2023).

In his rural studies, Scott called the former study of “bounce-back” resilience and the latter study of “bounce-forward”. Equilibrium resilience is about a system’s ability to absorb shocks and disturbances without undergoing major changes. Here, resilience is both how well a system resists disturbances and how quickly it returns to normal. A community’s ability to return to its pre-disaster state after an event is ideal. But is it good to return to normal after a disruption by shocks? The shocks may have shown hidden system weaknesses. As a result, the evolutionary approach does not seem to allow for changes. They cannot cause a modification or transformation in response to a crisis. Evolutionary resilience challenges the idea that communities should return to normal or “business as usual”. Evolutionary resilience involves adapting to shocks and disturbances through ongoing change. This process fosters adaptive behavior. Individuals or groups can transform this system into resilience through their actions characterized by finding new paths for development. This view also highlights the changing nature of social-ecological systems, including diverse actors with a range of social, economic, political, and ecological roles (Faulkner et al., 2020; Scott, 2021; Scott et al., 2021).

In practice, according to the principles of evolutionary thinking, resilience cannot be studied through one lens or one theory. A study of resilience must be more holistic. Many rural resilience researchers seek to identify key attributes to show that resilience is complex, multi-level, and multi-dimensional. This paves the way for shaping the evolutionary resilience of which society is an essential part (Dakos and Kéfi, 2022). In this context, the Hyogo and Sendai Frameworks have general principles with the sustainable development of communities in DRM as the core. Therefore, in the next part, the authors explain the framework of this study, which, based on these principles, helps us to move toward resilience indicators in small communities.

3. Research Framework

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) adopted the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) 2005–2015 to build communities’ resilience to disasters. This program presented a general action-oriented policy that, in addition to reducing the vulnerability of communities, tended to improve the resilience of communities (Horekens, 2007; Stanganelli, 2018; UNDRR, 2011; Oelreich, 2015). The Sendai Framework 2015–2030 is the successor instrument to HFA at the 3rd UN World Conference in Sendai, Japan, on March 18, 2015. The Sendai Framework is built on the elements that ensure the continuity of DRR undertaken under the HFA. It seeks to establish a concise, focused, forward-looking, and action-oriented framework on how societies can be more resilient in the post-2015 period (Aitsi-Selmi et al., 2015; Assarkhaniki et al., 2023; UNDRR, 2015). In early discussions, members stressed the need for specific tools, including indicators, to measure progress toward DRR and were encouraged to further develop such indicators at different national levels (Pearson and Pelling, 2015; UNDRR, 2015). The Sendai Framework sets the background. Then, at the national level, current and future challenges must be addressed. Therefore, there is a need to develop an operational framework for DRR and a set of indicators appropriate to the level of analysis. It seems that the authors can identify the local resilience indicators by learning from the Hyogo Framework and action priorities in the Sendai Framework. In this regard, Table 1 is an attempt to explore priorities at the small-community level for each of the actions in the Sendai Framework.

| Priorities for action | Local level | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priority 1: Understanding disaster risks |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Priority 2: Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risks |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Priority 3: Investing in DRR for resilience |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Priority 4: Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and ensuring “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

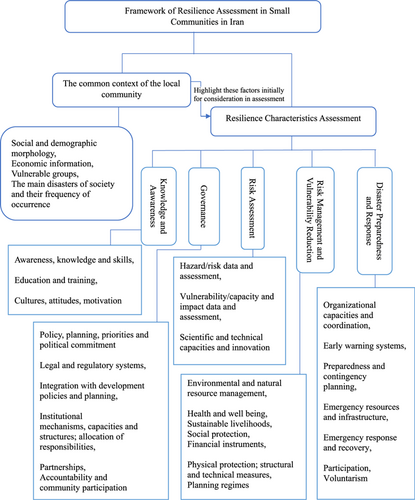

Two main categories can divide these priorities. The first category covers a local community’s common context. The second category covers the evaluation of resilience indicators. These two categories provide a context for analyzing a community’s resilience. In the first category, some data seems incomplete and insufficient, such as the number of female- or children-headed households, people with disabilities, vulnerable groups, for which the researcher can collect the data directly. This category serves to quickly assess the main risks and identify vulnerable groups, which should be listed first. Then, it is possible to consider them during resilience assessment. The assessment of resilience indicators is determined in the second category. In Fig. 1, the authors intend to determine these categories, indicators, and sub-indicators.

Fig. 1. Small community resilience research framework in Iran.

Source: Made by the authors.

4. Methodology

This study uses a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to investigate the proposed resilience framework in small Iranian communities. For a detailed investigation of the study, it is necessary to select one from the pilot samples1 that are being implemented and reviewed. These steps as mentioned by Yin (2009) are followed to select the sample. To begin with, the samples are listed and four factors of relevance, impact, comprehensiveness, and accessibility are considered to score them. Questions are asked in each component and each sample is given a score based on it. These questions are as follows:

| • | Relevance: How well does the case study illustrate the core concepts and functionalities of the framework? Does it showcase the framework addressing a specific challenge or problem it is designed to solve? | ||||

| • | Impact: Did the application of the framework in the case study lead to positive outcomes? Quantifiable results (data, metrics) can strengthen discussions. | ||||

| • | Comprehensiveness: Does the case study provide a clear picture of the situation before, during, and after the framework implementation? | ||||

| • | Accessibility: Is the case study data easy for the audience to understand? | ||||

A study case with the highest overall score, that is, Garmay Sara Village, is selected as the sample of this study. A quantitative method is used to collect first-hand and second-hand data on the general context of the community at the first step, including socioeconomic and demographic data that covers the identification of vulnerable groups, the main hazards faced by the community and how often they occur. Most of the data in this section require field observation and entering numbers. Also, there are some open questions in mind, such as identifying additional vulnerable groups, ethnic and religious groups, and geographic administrative assessment areas. Key informant interviews may be needed, for example, a nurse and a teacher can give detailed information on health and education. Their input is needed before the authors assess resilience. The main goal of this stage is to quickly assess the main risks and find the vulnerable groups. These groups include children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities. But they may also include female- or child-headed households, and persons with serious illnesses including Polio, which all depends on the context, for example, there are more people with thalassemia major in the rural areas of northern Iran than in other places. Also, the number of rural women who suffer from rheumatism is more than the average of the whole Iran. By highlighting these factors at the start, the authors can consider them when assessing resilience. At the second step, the authors use a qualitative method including field observations, document analysis, focus group discussions, and ethnographic methods. These methods will accurately assess community resilience. For a start, some conversation-starting guide questions are designed to explore the resilience characteristics in each component, based on the rating scale. Each of the five potential responses relates to a resilience characteristic, which corresponds to a resilience level from 1 to 5. Level 1 means least resilience and Level 5 means highest resilience. During the study, key questions should be answered based on the dialogue developed with community representatives, supporting tools and examples. If necessary, additional questions can be included to facilitate conversations. Table 2 shows the indicators, resilience components, and key questions. The authors draw inspiration from works of John Twigg (2009, 2015), Abenir et al. (2022) and FEMA (2023) to make a list of components and key questions.

| Sub-indicators | Resilience component | Key questions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and Education | Public awareness, knowledge, and skills | Public awareness and knowledge | Is there an open debate in the community, resulting in agreements about problems, solutions, and priorities for disaster risk? |

| Education and training | Dissemination of DRR knowledge | Do schools and oral tradition pass DRR knowledge to children? | |

| Cultures, attitudes, and motivation | Cultural attitudes and values on disaster recovery | Do the community’s attitudes and values, including expectations of help and self-sufficiency, religious and ideological views, contribute to its adaptability? Do they help it recover from shocks and stresses? | |

| Governance | Policy, planning, priorities, and political commitment | Community leadership in DRR | Is the community leadership in DRR committed, effective, and accountable? |

| Legal and regulatory systems | Rights awareness and advocacy | Does the community know its rights and the legal duties of the government and others who provide protection? | |

| Integration with development policies and planning | Integration with development planning | Do people see DRR as a key part of plans and actions to achieve broader community goals, cut poverty and improve quality of life? | |

| Institutional mechanisms, capacities, and structures; allocation of responsibilities/partnerships | Access to funding and partnerships | Are there clear, agreed and stable DRR partnerships between the community and other actors (local authorities, NGOs, and businesses)? | |

| Accountability and community participation | Inclusion of vulnerable groups | Do vulnerable groups in the community have a say in community decisions? Do they help manage DRR? | |

| Women’s participation | Do women take part in community decision-making and management of DRR? | ||

| Risk Assessment | Hazard/risk data and assessment | Hazard assessment | Has the community done risk assessments that involve the public? Has it shared the findings? Does it have people who can do and watch over these assessments? |

| Vulnerability/capacity (VCA) and impact data and assessment | Vulnerability/capacity assessment | Has the community done VCA? Has it shared the findings and does it have people being able to do and watch over VCA? | |

| Scientific and technical capacities and innovation | Local and scientific methods for risk awareness | Does the community use local knowledge and risk perceptions? Does it also use scientific knowledge, data, and assessment methods? | |

| Risk Management | Environmental and natural resource management | Sustainable environmental management | Does the community adopt sustainable environmental practices that reduce risk and adapt to new hazards from climate change? |

| Health and well-being | Access to health care in emergencies | Do health care facilities and workers serve the community? Are they ready to help with physical and mental health issues from disasters and small hazards? Do they have support from emergency health services and medicines? | |

| Health access and awareness in normal times | Do community members stay healthy and fit in normal times through proper food, hygiene, and health care? Do they know how to stay healthy and safe? | ||

| Food and water supplies | Does the community have enough food and water? Does it manage a fair distribution system during disasters? | ||

| Sustainable livelihoods | Hazard-resistant means of livelihood | Does the community use hazard-resistant means of livelihood for food security? | |

| Access to market | Do local trade and transport links to markets for products, labor, and services have protection? Are they protected against hazards and shocks? | ||

| Social protection | Social protection | Do the people have access to social protection schemes? Do these help reduce risks directly through targeted DRR? Or do these help indirectly through activities for socioeconomic development that reduce vulnerability? | |

| Financial instruments | Access to financial services | Are there affordable and flexible community savings and credit schemes? Or is there access to micro-finance services? | |

| Income and asset protection | Are household and community asset bases huge enough? Are they diverse enough to support disaster coping? They include income, savings, and property. Are there measures to protect them from disaster? | ||

| Physical protection; structural and technical measures | Infrastructure and basic services | Are the community’s buildings and basic services resilient to disasters and in safe areas? Do they use hazard-resistant construction and structural mitigation? | |

| Planning regimes | Land use and planning | Does the community consider hazard risks and vulnerabilities in land use decisions? | |

| Education in emergencies | Operation of education services in emergencies | Can education services operate without interruption during emergencies? Do they have the capacity to do so? | |

| Preparedness and Response | Organizational capacities and coordination | Capacities in preparedness and response | Does the community have an operating organization in disaster preparedness and response? |

| Early warning systems | Early warning systems | Is there an operational early warning system in the community? | |

| Preparedness and contingency planning | Contingency planning | Does the community use a contingency plan that accounts for the needs of vulnerable groups and is prepared in a participative manner and with the community’s context considered? | |

| Emergency resources and infrastructure | Emergency infrastructure | Are emergency shelters accessible to the community? Do they have enough facilities for all affected people? | |

| Emergency response and recovery | Emergency response and recovery | Does the community lead in response and recovery that reach all affected members and are prioritized by needs? | |

| Participation, voluntarism, and accountability | Volunteerism and accountability | Is there much community volunteerism in all parts of preparedness, response, and recovery? Does it represent all parts of the community? |

At this stage, the authors held several focused group discussions involving 6–15 people. The authors intended to include a range of opinions from different parts of the community. Village council, mosque, clinic, and primary school were the places easy for focused group discussions. Also, some occasions such as Muharram, harvest festival, and Aros Goli gave the research group an opportunity to talk with the villagers in different groups. For example, harvest festival, the purpose of which is to give thanks for the harvest, is a good time to talk about people’s livelihoods and economy and to understand the culture of the community. In the clinic and primary school, the authors talked better with women. Especially with the help of the school officials, meetings were arranged with the students’ mothers and it was possible to identify the vulnerable groups and talk with them in clinics. Some of the gatherings of old women in front of houses led to sincere conversations with them. Meetings were held with men in traditional coffee houses.

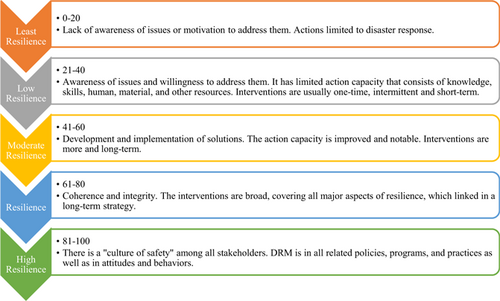

Structured dialogues were developed collaboratively on community resilience. The authors also attempted to create a plan for discussion in the local dialect, which is appropriate to the context, and ensure consistent use of the language. At the beginning of the meeting, the group introduced themselves and ensured that the importance of the study was understood by the participants. Before posing the key questions in each component, some general open questions were raised, including what is the most important problem of this village? Or what is the most important natural hazard that threatens the village? Then the key questions were asked, such as social support status or help in emergency situations. In between talking and commenting, they were asked to give an example or case that comes to their mind. Also, the completion of the survey was done collaboratively and the consensus of the participants was followed to reduce disparities in the data collected. Finally, they graded community resilience as a percentage after analyzing the focused group discussion on each component. Then, as shown in Fig. 2, five spectra were considered to determine the resilience levels.

Fig. 2. Resilience levels and characteristics of each level.

Source: Made by the authors.

5. Results

Located at 37∘03′05′′N and 50∘15′56′′E, Garmay Sara is one of the villages of Amlesh County in Gilan Province. At present, the authors estimate that the population of this village is 374 people. Vulnerable groups include two people with physical disabilities and two people with mental disabilities. Also, there are 22 female-headed households. Table 3 shows the demographic information of this community.

| Groups | F | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Information | Men | 153 |

| Women | 172 | |

| Population | 325 | |

| Households | 122 | |

| Vulnerable Groups | Female-headed Households | 22 |

| Physically Disabled | 2 | |

| Mentally Disabled | 2 |

The region’s most important hazards include range movements (landslides), floods, and earthquakes. This area is in a place with a high risk of earthquakes and features six active faults. The historic Rudbar earthquake caused much harm to people and property here. Garmay Sara is on a plane bed where flood and alluvial plains form its natural habitat, making this area prone to landslides and floods. Hazards like floods, blizzards, and frosts close roads for days and harm the community every year. The average rainfall in this area reaches 850mm and causes floods together with many seasonal and permanent rivers. In the following, the authors examine the different dimensions of resilience indicators in the community.

5.1. Governance

The governance indicator is evaluated with six questions. The evaluation shows that the indicator is weak, with a score of 16 out of 30. As seen in Table 4, community awareness of its rights and government obligations and the existence of DRR in community programs and actions are higher than other questions (Level 4). The findings show that the local community knows its rights and the legal duties of the government and the main actors who give protection well. The main issue is that the local community’s awareness and advocacy of their rights are not at a high level due to their low participation. People have a low say in decisions and see the government as the one who decides and acts to improve their lives. The top-down approach is common in Iran’s planning system, making people rely on the government and keeping them from joining the plans.

| No. | Questions | Level | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Is the leadership of the community committed, effective and responsive? | The leaders are committed but not effective due to the use of scattered, short-term measures in rare cases of responses | 2 |

| 2 | Does the community know its rights and the legal duties of the government and others who provide protection? | The community knows its rights and the legal duties of government and others who provide protection. The government seldom calls them and feels the need for their participation | 4 |

| 3 | Do people see DRR as a part of plans to achieve community goals, cut poverty and improve quality of life? | The community understands the importance of DRR and has documented DRR actions in local plans to achieve wider goals. But they only occasionally use the DRR actions | 4 |

| 4 | Are there clear, agreed and sustainable DRR partnerships between the community and other actors (local authorities, NGOs, and businesses)? | The community has agreed but unstable and unclear DRR partnerships with other actors, providing one-time and piecemeal access to funds or resources | 2 |

| 5 | Are vulnerable groups included in DDR decision-making and management? | Sometimes, some vulnerable groups take part in decision-making on DRR. But they usually do not occupy positions in the main body | 2 |

| 6 | Do women take part in decision-making and DRR management in the community? | Sometimes, women join in decision-making on DRR. Yet, they usually do not occupy positions within the main decision-making body | 2 |

Several natural hazards in the past have led to the existence of programs for the DRR. For example, since 1996, earthquake maneuvers have been ongoing at schools and offices. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the local community started informing and disinfecting, distributed masks and registered vaccines to help the needy and sick. With the government’s support through health trainings and skills, an atmosphere for people’s participation was created. But after that, such voluntary movements were not organized and continued. The local community knows that DRR plans lead to local development. But the needed structures and supports for them have not been made. In terms of leadership commitment, effectiveness, and accountability, leaders prefer to act only in crises and emergencies (Level 2). Local leaders are often in the village mosque and reachable to everyone. They are good listeners for people’s problems and demands but rarely fix them. During the snowfall of 2018, which caused much damage, local leaders, including village headmen, council members, and mullahs, helped officials estimate the damage. They interacted effectively with the institutions, which is an example of leaders solving problems. But when the community is in balance, the leaders take no action. In short, the results showed that community’s leaders only consider themselves obliged to act during a crisis. In DRR participations, the public is well aware of their rights and the duties of the government. The government’s obligations to the community are clear but not fulfilled in a transparent way (Level 2). The community knows that to reduce disaster risks, the government must meet obligations and provide funds. But these measures are unstable, unclear, and temporary. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Health House carried out some awareness-raising measures but stopped them after the pandemic subsided. These measures should be continued to increase compliance with the community’s health rules.

The findings show that the village has two physically disabled people and two mentally disabled people. These people sometimes join community gatherings. However they lack a place and a voice in community’s decision-making (Level 2). Most importantly, they cannot assert their rights and thus become subject to decisions and actions. They are not given attention and their interests, conditions and needs are neglected. For example, during the authors’ visit to the village mosque, the social and physical center of the community, the stairs and interior design did not consider people with disabilities.

In terms of women’s participation, the women of the community sometimes help make the community’s DRR decisions and have the chance to register as candidates for the local government, though no woman has ever become a candidate besides attending public gatherings (Level 2). The conclusion is that women do not have a great desire to participate in DRR. They are put off by the community’s male-dominated culture and by the demands of housekeeping and childcare.

The results show that in governance, policies and measures are not inclusive enough or at an acceptable level. It is needed to give the people a larger role, use bottom-up planning, and enable the local community to participate. Society is a system with local communities, local government, and central government as its key parts. Good interaction and participation between them will promote risk reduction.

5.2. Risk assessment

The risk assessment team investigated the three issues shown in Table 5 and found they are in an acceptable status. The team assessed the participatory risks and made the results public. Various organizations, including the Geological Organization of Iran, prepared maps of high-risk areas at regular intervals. The local community supported these actions and helped the representatives of those organizations. The climate of this community makes floods likely. By predicting floods, the meteorological organization warns the people through mass media. The VCA in the community is done through combined efforts by the community and government institutions, in which case the community uses local methods while the government institutions use scientific methods (Level 4). The VCA is usually conducted before and after any risk occurs. For example, when the meteorological organization announced the risk of floods, some people took on the task of warning the flood-prone fields. During the COVID-19 outbreak, some members told others about the virus, handed out donated health packs and controlled entry to the village.

| No. | Questions | Level | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Has the community done a risk assessment that involves the public? Has it shared the findings? Can human resources (HR) do/update these assessments? | Risk assessment and risk mapping have been done and are being used. The findings are available to the public | 3 |

| 8 | Has the community assessed vulnerability and participatory capacity? Have the findings been shared? Can HR do and update these assessments? | Participatory VCA has been conducted but the findings have not been fully shared with the community | 4 |

| 9 | Does the community use local knowledge and risk perceptions? Does it also use other scientific knowledge, data and assessment methods? | The community understands risks locally. But this awareness does not always match data or science | 2 |

The indicator of local knowledge and risk perceptions shows that the community is well aware of the risks in the environment. Some of the perceptions come from life experiences in the environment, some come from experiences shared between generations, and some come from raised awareness. The local community knows the need to find and guard against hazards to make it less vulnerable to disasters.

5.3. Knowledge and education

In Table 6, the knowledge and education indicator was investigated for three issues: knowledge and public awareness, dissemination of risk reduction knowledge, and cultural attitudes and values. In this village, in addition to its religious and political centers, the mosque is also a place for serious meetings, gatherings and discussions about problems and challenges, which are publicly organized on Fridays after prayers, often attended by local leaders and even provincial leaders, and can be joined by all members of the community. Some meetings are held on an emergency basis. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a meeting was held in the village with local leaders, of which the focus was to prevent non-residents from entering with the help of local forces. In general, the key point is that sessions do not always end in agreement or in action and participation. During an emergency, an agreement to help is often reached because of a directive management system in regional management (Level 2).

| No. | Questions | Level | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Is there an open community discussion? Does it lead to agreement on problems, solutions, and priorities about disaster risks? | So far, there has been few open discussion on the problems, solutions, and priorities related to disaster risks. And few people have joined in the discussion | 2 |

| 11 | Do local schools teach DRR knowledge? Or is it passed down through oral tradition from generation to generation? | The oral tradition transmits some experiences. Schools do not transmit related knowledge and experience | 2 |

| 12 | Do the attitudes and values of the community allow for adaptation and recovery? | Cultural values play an effective role in adapting to shocks and stresses, which has contributed to a high level of social cohesion | 4 |

The community has faced many risks all the time. In the past, this forced the community to use shared wisdom to make solutions and strategies to reduce risks. The region is prone to heavy but irregular rains, making it impossible to use 100% of the rains. So, the community built structures like a wetland to grow common carp fish and store water for drinking and farming, and some of the structures are still active. This indigenous knowledge is generally transmitted orally. During parties, the elders share the solutions they have in facing problems through memories, experiences, quotes, and stories for the young. In schools, the uniform national curriculum and non-native teachers make it impossible to present native knowledge (Level 2). Thanks to its shared ethnic and religious roots, the community features acceptable social solidarity, empowering it with a favorable recovery capability during disasters. Despite the non-native people in the community, there has been no distinction in helping people during crises (Level 4).

5.4. Risk management and vulnerability reduction

The areas related to risk management are highlighted in Table 7. The first indicator is about sustainable environmental management. It refers to practices that aim to integrate the management of land, water, and other environmental resources. The goal is to meet human needs while ensuring long-term sustainability, ecosystem services, biodiversity, and livelihoods. There is no sign of such actions for a more sustainable life. For example, this community knew very little about climate change and its effects, lacked adaptation strategies for climate change, and did not manage land, water, and other environmental resources well (Level 2).

| No. | Questions | Level | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Are sustainable environmental management measures taken to reduce the risks caused by new risks related to climate change? | There are very few sustainable environmental management practices; and no measures have been taken to adapt to new risks | 2 |

| 14 | Do the residents have access to health and treatment centers? Are these centers staffed by well-equipped and trained health workers? Can they handle medical emergencies? | There is a health center equipped with trained personnel | 3 |

| 15 | Do the members of the community have good nutrition, health, and physical ability in normal times? | Most of the members of the community have good health and physical ability | 4 |

| 16 | Does the community have a safe source of water and food? | Most households have food storage, but its performance is poor | 3 |

| 17 | Does the community use sustainable means of livelihood for food security? | Most of the members of the community have some resistant means of livelihood individually | 3 |

| 18 | Are communications, transportation, and local trade protected against risks and shocks? | The community is very vulnerable to such shocks | 2 |

| 19 | Do social protection plans reduce risks through targeted DRR activities or indirectly through development activities? | The community has limited access to official social protection schemes They only have access to indirect ones | 3 |

| 20 | Are there suitable and flexible credit facilities? Is there access to finance services, formal or informal? | There is access to financial services. But not everyone has them due to bureaucracy and financial requirements | 3 |

| 21 | Are household assets large enough and diversified enough to protect them against disasters? | Households have learned to spread their assets over time and resist risks on a small scale | 3 |

| 22 | Are infrastructures and buildings resistant to disasters? | Most of the buildings are old. They are in unsafe areas. Some retrofitting measures are underway | 2 |

| 23 | Have the development plans paid attention to the reduction of vulnerabilities? | This has been taken into account in the village development and land use plans | 4 |

| 24 | Can educational services keep working in emergencies without interruption? | The school does not have a safety plan or emergency committee. Disasters lead to the suspension of school activities | 2 |

There is a well-equipped health center in Garmay Sara for training health workers and providing the equipment and medicines needed for care. The center can also refer emergency cases to city and provincial hospitals and health centers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this center offered the necessary care for patients as the region’s vaccination center (Level 3). This center should have a regular program to check the health of babies, children under 5 years old, the elderly, and pregnant and lactating women, but these services they deserve are in the early stages. Recently, families have been trained to take care of sick children suffering diarrhea and fever, and taught with sexual hygiene knowledge. Besides, the vulnerable groups are regularly examined (Level 3).

Rice, tea, citrus fruits, wheat, and barley are cultivated in the Garmay Sara and some families have stored them as much as they need for emergencies. However, there is no plan for a massive food reserve. Also, floods once caused water supply cuts and water contamination in the village. Despite this, the village has not yet planned to put in place water storage tanks or a method for water storage. Only the Red Crescent of Amalesh City has a warehouse to store food, water, clothes, and tents for emergencies (Level 3). Inflation has caused most people to take up many activities in addition to farming, such as peddling, making food by-products, and selling cattle, during unemployment in nearby cities, as the means of livelihood (Level 3). The communication network of the region is not in an acceptable status. Roads are usually blocked by snow, rain or landslides. During the snowfall of 2021, the village’s road was fully blocked. These unsuitable roads have caused non-native workers to demand more pay for farm work and increased the risk of economic activities in the village (Level 2). Social protection includes the official government’s measures to support farmers, and the support provided by the Islamic Revolution Housing Foundation for building housing. Non-official methods include helping vulnerable people during disasters. The government’s measures only indirectly reduce risks (Level 3). In recent years, the government has defined various facilities for rural areas, including retrofitting of rural houses, loans for rebuilding homes after an accident, insurance for gardeners and farmers, and agricultural loans. These facilities are mainly provided to the public by state banks. Despite these diverse facilities and social protection, the loan process, the guarantees, and the repayment method make them unusable for all (Level 3). People’s main assets are properties, such as farms gardens, gold, and cash. Recently, buying dollars, investing in stocks, and even digital currencies have become part of people’s investments. Due to the inflation of the past years, most people do not want to save their assets in banks (Level 3). For the power and gas outages, communication disruptions, water pollution, and main road closures that occurred in the past years, no steps have been taken to make the village more resilient. New buildings must follow the construction rules and rural development plans. Although most homes are in flood and landslide zones, some risk reduction measures have been put in place (Level 2). Garmay Sara’s development plan sets the way of expansion, organizes land uses and considers long-term risks (Level 4). Educational services are closed during emergencies. Schools’ security and reinforcement programs are not followed. Recently, the rise of online education infrastructure has helped the access to education services (Level 2).

5.5. Preparedness and response

The Red Crescent and the Crisis Management Organization are among the most important organizations that work during crises. These organizations have two duties: offer aid and educate people. They educate people by working with schools, radio, TV, and some organizations and institutions. It seems that these trainings have been effective in reducing the risk. For example, during the flood in 2018, the people who took Red Crescent courses were able to help the injured. Besides, the authors found that 5 months ago, a fire in the village was contained because one of the residents who had passed firefighting courses was there. Even though, more residents should be attracted to participation (Level 4). Table 8 shows the status of the preparedness and response indicators.

| No. | Questions | Level | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Is there a trained and operational organization in the field of risks? | Red Crescent and Crisis Management Organization react in crises | 4 |

| 26 | Is there an early warning system? | The weather forecast system is the only early warning system | 3 |

| 27 | Does community have a plan to protect itself? | There is no program | 1 |

| 28 | Is there a shelter with enough facilities? | The mosque acts as a shelter in case of emergency. But its facilities are not enough | 3 |

| 29 | Is there a response and recovery protocol and measures taken? | There is no prioritization or special protocol | 2 |

| 30 | Is there a high level of volunteerism? | There is a high level of volunteerism. But people are not organized into local teams and do not follow a specific protocol | 2 |

Only flood and snow forecasts can provide information. Until now, the people had no experience in quick evacuations but know that the community and their lives are vulnerable to earthquakes and floods (Level 3). There is no cooperative planning to protect people. The authors asked the local leaders and checked the archive of meetings and actions, in which no plan was made to support and protect themselves (Level 1). During an emergency, some houses and the village mosque act as a shelter. However, the facilities are not enough for all the affected people (Level 3). Volunteerism is in an acceptable status, but most volunteers are untrained and need to improve their skills and practice teamwork in times of danger. First aid training and how to respond to danger should be offered more widely. Local voluntary teams should also be formed (Level 2).

5.6. Calculation of resilience indicators

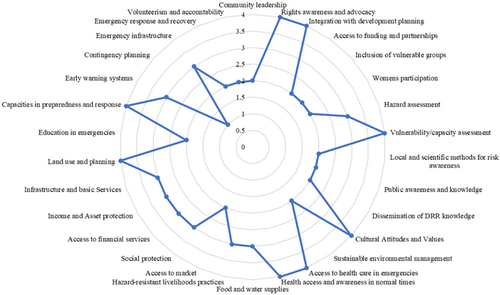

Figure 3 shows the status of indicators and sub-indicators of resilience in Garmay Sara. The resilience level of Garmay Sara is equal to 56. This level equals a normal resilience. The community has taken measures to improve it. But many of these measures are partial and short-term. Meanwhile, some long-term measures can also be identified. The community has improved its crisis capacities. However, it needs sustainable land management, which will help community become resilient.

Fig. 3. Status of indicators of resilience assessment in Garmay Sara.

Source: Made by the authors.

6. Discussion

Rural areas and small towns in Iran are more vulnerable to natural hazards. The lack of accurate and up-to-date information about them makes it impossible to use common resilience calculation methods. So, there is a need for a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. The study aims to provide a framework for examining resilience in rural areas and small towns in Iran by use of a participatory and people-centered approach. Researchers investigated the proposed framework in Garmay Sara, with the results showing that the local community has taken some steps to reduce the risks with help from government and quasi-governmental institutions. Leaders only take executive actions in crises and feel obligated to act only then. Under normal conditions, the government indirectly supports risk reduction through financial facilities or development plans and has no will to encourage residents’ participation. The residents rely on the government and see it as obligated to provide services. Local leaders are part of the community and fully available and can link the central government and the local community. It also seems that the government has more flexibility in entrusting affairs and decentralizing decisions and giving more role to people in small communities. If these local leaders move toward risk reduction, they can strengthen the trust and legitimacy of political structures. They can really create opportunities to decentralize administrative and political affairs and cause people’s active participation and be a springboard for local development. Although now, residents do not effectively and continuously take part in decision-making, investment, and implementation for risk reduction, trained organizations take responsibility for the initial response in necessary cases. Education is also part of the program of these organizations. Most people have an economic base that they can rely on for a short period of time when crises occur. The community features an acceptable level of social cohesion, and in general can be considered to have an average level of resilience, which requires more stable and long-term measures for reducing disaster risks and land management. Recommendations can also be made to improve the resilience of Garmay Sara. Community training programs using local capacities should be held regularly. It seems feasible to create some awareness campaigns related to disasters like floods. Upgrading and strengthening critical infrastructure such as schools and health care centers and houses should be prioritized. Water management systems should be improved and resources and training should be provided to local farmers to adopt sustainable farming techniques. It is necessary to establish microfinance schemes and affordable insurance options, enforce land use plans that consider disaster risk and prevent building in high-risk areas, and install reliable early warning systems that can provide timely warnings to residents. It is also necessary to create a mechanism to monitor community resilience.

7. Conclusions

Risk reduction seems closely related to quality of life. The goal of risk reduction is to shape communities for a better life and motivations for risk management is to serve economic and social well-being. If they are met, DRM will become stronger. Ignoring DRM can harm the economy and ecosystem and lose people’s and investors’ trust. Frequent incidents with low and moderate effects and single incidents with severe effects in such a community can even destroy social life, if it can seriously damage the vital arteries of the community. Thus, there is a need for comprehensive DRM. Moreover, resilience in small communities should be assessed with the help of people and local leaders, with dialogue and conversation as the basis. This process leads to mutual thinking and a better understanding of the community. In this context, three factors, namely strengthening social cohesion, allocating resources, supporting local leaders, and strengthening decentralization, seem to play a vital role. Policies should aim to strengthen social cohesion by fostering public dialogue and active participation in risk management. The DRR initiatives need adequate funding and incentives. Empowerment of local leaders can bridge the gap between the central government and residents, enhancing trust and legitimacy in political structures. Finally, Policymakers should promote flexibility in the centralized planning system to entrust local communities with greater decision-making authority and responsibilities. The goal of DRR assessment is not only to get an image of the risks, but also to create a platform for discussion among community members and to form active social groups. An important part of the DRR is to start an ongoing conversation with the public. People’s discussions should lead to step-by-step and continuous actions. Small communities sharing their experiences help them update and improve their actions. It should be ensured that all departments understand their role in the DRR. A budget should be allocated to reduce the vulnerability to disasters and incentives should be provided to the residents. After each disaster, the local community must ensure that meeting the survivors’ needs is central to the reconstruction and support the survivors in planning and carrying out the rehabilitation and response plans, including rebuilding homes and businesses. Residents should voluntarily participate in strengthening preparedness programs, early warning systems, and disaster risk capabilities.

This study is limited by the lack of an operational framework for measuring resilience in Iran’s small communities. Resilience measurement techniques have come a long way in the past decade. However most of the progress has been made in improving validity rather than usefulness and ease of use. No one has developed frameworks that enable local communities to assess and discuss resilience. The authors intend to provide such a people-oriented dialogue framework. However, it needs more assessment and use in small Iranian communities to help it improve and change into a complete version. Besides, this study is also limited in creating an active dialogue with the residents. Residents have not learned to talk and interact with each other. It is hard for them to talk with the research group. Furthermore, in Iran’s small communities with traditional culture, talking and engaging with women and girls face restrictions that reflect broad social restrictions, making it hard to create a dialogue with them.

In the future research, researchers can look into how to make interactive and conversational methods that will help community members talk to each other more easily. Talking about the dangers that face them and presenting solutions with their help is a platform for a community with more vitality. Also, researchers can examine how to form volunteer cores to reduce risks in a small community. And it is useful to provide guidelines that help the local community reach people-centered and voluntary solutions to reduce the hazard risks.

ORCID

Mojtaba Valibeigi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7902-4923

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7902-4923

Ali Akbar Taghipour  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5672-9667

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5672-9667

Parsa Ahmadi Dehrashid  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9117-453X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9117-453X

Kouros Asvadi  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-5780-1034

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-5780-1034

Notes

1 It should be noted that eight pilot samples are being investigated and implemented by the research group. In this study, one of them should be selected for a detailed examination of the various dimensions of the proposed resilience framework through interviews with rural planners and developers. These pilot samples have been selected from eight different regions of Iran based on indicators of geographical diversity, natural hazards, racial, and religious diversity.