LOG-NORMAL STOCHASTIC VOLATILITY MODEL WITH QUADRATIC DRIFT

Abstract

In this paper, we introduce the log-normal stochastic volatility (SV) model with a quadratic drift to allow arbitrage-free valuation of options on assets under money-market account and inverse martingale measures. We show that the proposed volatility process has a unique strong solution, despite non-Lipschitz quadratic drift, and we establish the corresponding Feynman–Kac partial differential equation (PDE) for computation of conditional expectations under this SV model. We derive conditions for arbitrage-free valuations when return–volatility correlation is positive to preclude the “loss of martingality”, which occurs in many traditional SV models. Importantly, we develop an analytic approach to compute an affine expansion for the moment generating function of the log-price, its quadratic variance (QV) and the instantaneous volatility. Our solution allows for semi-analytic valuation of vanilla options under log-normal SV models closing a gap in existing studies.

We apply our approach for solving the joint valuation problem of vanilla and inverse options, which are popular in the cryptocurrency option markets. We demonstrate the accuracy of our solution for valuation of vanilla and inverse options.a By calibrating the model to time series of options on Bitcoin over the past four years, we show that the log-normal SV model can work efficiently in different market regimes. Our model can be well applied for modeling of implied volatilities of assets with positive return–volatility correlation.

1. Introduction

Empirical studies strongly support evidence that the volatility of price returns is itself a stochastic process (see, for example, Shephard (2005) for a comprehensive survey). It is accepted that the celebrated model by Black & Scholes (1973) and Merton (1973), which assumes constant volatility, cannot explain implied volatility surfaces observed in option markets, which are inhomogeneous in strike and maturity dimensions. In contrast, stochastic volatility (SV) models are able to fit to implied volatility surfaces and their dynamics.

1.1. Evidence of log-normality of implied and realized volatilities

Applications of log-normal SV models, which are based either on the log-normal dynamics for the instantaneous volatility or on the Gaussian dynamics for the logarithm of the volatility, are widespread in practice. Predominantly, SABR model by Hagan et al. (2002) is widely used among practitioners for fitting implied volatility surfaces. However, for modeling the dynamics of volatility surfaces, we need to account for the mean-reversion of the volatility process like in conventional SV models. The mean-reversion ensures that the distribution of the volatility has a stationary long-run distribution and volatility paths simulated in Monte Carlo (MC) do not explode. In another widely used specification, the so-called Exp-OU specification, the SV process is defined for the logarithm of the volatility.b

In an excellent study Christoffersen et al. (2010) examine the empirical performance of Heston (see Heston (1993)), log-normal and 3/2 SV models using three sources of market data: the VIX index, the implied volatility for options of the S&P500 index, and the realized volatility of returns on the S&P500 index. They found that, for all three sources of data, the log-normal SV model outperforms its alternatives. Tegner & Poulsen (2018) report similar finding using realized volatilities.

1.2. Analytical tractability

Log-normal SV models cannot be handled by semi-analytic Fourier methods available for affine SV models. The analytical intractability may have lead to a slow adaptation of log-normal SV models in spite of their empirical support. On the one hand, the log-normal SV model with the linear drift does not belong to the family of affine diffusions because the so-called admissibility conditions are not satisfied for the variance term, see Duffie et al. (2003), Filipović & Mayerhofer (2009). On the other hand, the log-normal SV model with the quadratic drift does not belong to a general family of polynomial diffusions, see Filipović & Larsson (2016), Cuchiero et al. (2012). Carr & Willems (2019) introduce measure change to relate the model to a class of polynomial diffusions, which comes at cost of introducing an additional state variable. Authors then approximate the payoff function using an orthogonal polynomial expansion, see Ackerer & Filipović (2020), for option pricing applications. A related approach for computing moments under SV models using expansions is developed by Alòs et al. (2020).

We contribute to these studies by developing a closed-form approximate and very accurate solution for the log-normal SV model which enables analytical intractability of this model. We develop an affine expansion to derive closed-form solution for the moment generating function (MGF) of the log-price process, volatility and its quadratic variance (QV). We show that our solution to the MGF produces valid probability density functions of the state variables, which are matched with MC simulations.

1.3. Properties of log-normal SV model

In a related research, Lewis (2018) introduces a log-normal SV model with a quadratic drift without constant term. Lewis (2018) suggests to apply the model only when return–volatility correlation is negative because, otherwise, the model leads to the loss of martingality. Carr & Willems (2019) introduce the log-normal SV model with the quadratic drift, similar to our model. In our paper we augment the log-normal SV model with the linear drift term introduced in Karasinski & Sepp (2012) to include the quadratic drift term. We contribute to studies of Lewis (2018) and Carr & Willems (2019) by defining the martingale conditions under both MMA and inverse martingale measures. We also formulate the Feynman–Kac theorem linking the model dynamics with the quadratic drift to the partial differential equation (PDE) approach, because the classic Feynman–Kac does not apply to non-Lipschitz coefficients. We then introduce the MGF as the solution to the model PDE and develop an analytic transform-based approach for the valuation of vanilla and inverse options.

1.4. Assets with positive return–volatility correlation

Carr & Wu (2017) propose the following three economic factors behind the negative return–volatility correlation, which most typically observed in the dynamics of stock prices and stock indices: aggregate financial leverage, systematic risk, positive auto-correlation of negative shocks. However, in many markets we actually observe price dynamics with positive return–volatility correlation either on a permanent basis (for VIX index, short and leveraged short exchange-traded funds (ETFs)) or on a transitory regime-based basis (for some commodities, foreign currencies, and cryptocurrencies). In fact, exp-ou and log-normal SV models with the linear drift lead to the “loss of martingality” of the price process when the return–volatility correlation is positive (see, for example, Lewis (2000, 2018) and Lions & Musiela (2007)). We contribute by establishing conditions on model parameters of log-normal SV model which produce true martingale dynamics.

1.5. Inverse martingale measure

For inverse options, both option premium and final payoff are quoted in the units of the underlying asset. In particular, for options on cryptocurrencies, the advantage of inverse payoffs is that all option-related transactions can be handled using units of underlying cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin or Ether, without using fiat currencies (see Lucic (2021) and Lucic & Sepp (2023) for a connection between the valuation of the inverse cryptocurrency options and FX options). In case of cryptocurrencies, cash settled options would require using a stablecoin as a tradable equivalent of United States Dollar (USD) or any other fiat currency. Given inherent and frequent depegging risk of stablecoins, Alexander et al. (2023) argue for wider adoptation of inverse and quanto options. We also suggest that similar payoff can be advantageous for some commodity markets (such as gold) where option holders may opt for physical settlement of positive option premium through the delivery of the underlying commodity.

We contribute to the literature by incorporating the inverse measure in our valuation framework using log-normal SV model. We formulate and solve the joint valuation problem of vanilla and inverse options using Fourier transform methods.

1.6. Organization of the paper

In Sec. 2, we provide the framework for valuation under money-market account (MMA) and inverse measures. In Sec. 3, we introduce the log-normal beta SV model with quadratic drift and establish important properties of the volatility process. We further characterize martingale property for the drift-adjusted price process and its inverse under MMA and inverse measures, respectively. We also study moments of the volatility process by presenting an approximate solution of the finite-dimensional linear system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Finally, we present drift-implicit Euler scheme for MC simulation that preserves the positivity of the volatility process and study its convergence properties. In Sec. 4, we present first- and second-order affine expansion for the MGF of the log-price process, the QV and the volatility. In Sec. 5, we apply affine expansion to derive closed-form solutions for option valuation problem under MMA and inverse measures. In Sec. 6, we apply our method for model calibration to market data and demonstrate the accuracy of both the model specification and our proposed solution methods. We conclude in Sec. 7. Technical proofs are provided in Appendix A.

2. Framework and Definitions

2.1. Vanilla and inverse payoffs

The payoff of (cash-settled) vanilla options is settled in the units of cash. In contrast, the payoff of an inverse option is settled in the units of the underlying asset using the spot price observed at the option maturity. We denote the spot price at time T by ST and option strike price by K, with both quoted in United States Dollars (USD). We consider vanilla call and put payoffs settled in USD cash at maturity time T and denote them by

2.2. Valuation under equivalent MMA and inverse measures

We consider a continuous-time market with a fixed horizon date T∗>0 and uncertainty modeled on probability space (Ω,𝔽,ℙ) equipped with filtration 𝔽={ℱt}0≤t≤T∗. We assume that 𝔽 is right-continuous and satisfies usual conditions.

2.2.1. Spot markets

Assumption 2.1. Risk-free rate r(t) is deterministic with the value of one unit of the MMA M(T) given by M(T)=eˉr(0,T), ˉr(t,T)=∫Ttr(s)ds.

We assume that the market is complete and satisfies the so-called No Free Lunch with Vanishing Risk (NFLVR) and No Dominance (ND) conditions (see Jarrow & Larsson (2012)). By choosing M as a numéraire, we consider an equivalent martingale measure ℚ, induced by M. Accordingly, the time-t value of an option, denoted by U(t,S), with payoff function u(ST) at time T, equals

Next, by choosing spot price S as a numéraire, we consider an inverse martingale measure ˜ℚ, induced by S. The option value function, denoted by Ũ(t,S), with the payoff paid in units of S, equals

Theorem 2.1. We assume that market is complete and satisfies NFLVR and ND conditions. We further assume that both MMA measure ℚ and inverse measure ˜ℚ are equivalent martingale measures. Then the values of options under MMA measure in Eq. (2.3) and under inverse measure in Eq. (2.4) are unique and satisfy

Proof. As shown in Theorem 3.2 of Jarrow & Larsson (2012) and Theorem 2.17 of Herdegen & Schweizer (2018), the market satisfies NFLVR and ND conditions if and only if ℚ is a true martingale measure. Hence, asset prices, discounted by numéraire M are true ℚ-martingales. Consequently, due to the uniqueness of price, the equality in Eq. (2.5) holds. To justify the equality of both sides, we apply the existence and uniqueness of equivalent inverse (true) martingale measure ˜ℚ for the numéraire S, see Theorem 4.4 and Corollary 3.11 in Herdegen & Schweizer (2018). □

2.2.2. Futures markets

Since most option markets for commodities and cryptocurrencies are based on futures, we also adopt our methodology for futures options. We consider a set of futures contracts settled at times {Tk}k=1,…,K with prices {FTkt}k=1,…,K.

Assumption 2.2. The convenience yield q(t) of futures prices is deterministic with the integrated convenience yield given by

Definition 2.1. Measure ˜ℚT induced by price FTt with futures maturity at T, T∈{Tk}, chosen as a numéraire is called the inverse T-futures measure.

Corollary 2.1. We assume that market is complete and satisfies NFLVR and ND conditions. We further assume that both MMA measure ℚ and inverse futures measure ˜ℚT are equivalent martingale measures. Then option values under MMA and inverse measures are unique and satisfy

For markets with both vanilla and inverse options being tradable, such as cryptocurrency markets, any SV model applied for joint valuation of options across several exchanges and contract specifications must satisfy the conditions (2.5) and (2.7). For the proposed log-normal SV dynamics in Eq. (3.12), we must impose certain conditions on model parameters, which we address in Theorem 3.7.

2.2.3. Put–call parity

We will discuss an important topic of the put–call parity for inverse options under a generic SV model with SV driver σt. We establish that the put–call parity is valid if volatility σt is not explosive.

Lemma 2.1. We assume that volatility process σt is nonexplosive under ℚ. Then put–call parity for vanilla call option, C(t,S,K), and put option, P(t,S,K), defined by

We assume that volatility process σt is nonexplosive under ˜ℚ. Put–call parity for inverse call option, ˜C(t,S,K), and inverse put option, ˜P(t,S,K), defined by

Proof. We only provide a sketch of the proof and refer to Theorems 9.2 and 9.3 in Lewis (2000) and to Sin (1998) for details. As vanilla call option payoff is unbounded, the price of the call option is only local martingale under ℚ. Taking into account “correction” term (so-called martingale defect) reflecting the difference between true martingale and strict local martingale properties, yields Eq. (2.8). Relationship in Eq. (2.9) follows from the same argument, but applied to ˜ℚ. □

In Theorem 3.2, we show that volatility process σt does not explode under the proposed log-normal SV dynamics in Eq. (3.12).

3. Log-Normal Beta SV Model

3.1. Dynamics under ℙ measure

We start with statistical ℙ measure and we consider the log-normal beta SV model introduced by Karasinski & Sepp (2012). We augment the dynamics with the quadratic drift in the volatility process following Lewis (2018) and Carr & Willems (2019). We first introduce the dynamics of price process St and volatility process σt under statistical measure ℙ as follows :

Empirically, Bakshi et al. (2006) find that the presence of nonlinear terms, including the quadratic term, in the volatility drift is significant when using econometric estimation of the dynamics of the VIX index.

We assume that statistical measure ℙ and MMA measure ℚ are related by

Assuming that process ζ(t) is a true martingale, the following processes

As a result, the dynamics of volatility process under MMA measure ℚ become

As customary,c we assume that the market price of risk is proportional to the volatility as follows :

To retain the functional form of the volatility process, we rescale model parameters ̂𝜃, ˆκ1, ˆκ2 under ℚ as follows :

Thus, under martingale measure ℚ, the dynamics of price and volatility processes become

Theorem 3.1. We assume that κ1≥0, 𝜃>0. Then measures ℙ and ℚ are equivalent, iff

Proof. By analogy to the proof of Theorem 3.6. □

As a result, we obtain that the functional form of log-normal SV model with the quadratic drift is invariant under the change of measure from ℙ to ℚ. We note that the log-normal volatility model with linear drift does not share such invariance property due to a quadratic term arising under ℚ. The model invariance under the change of measure is an important feature shared by the log-normal SV model with quadratic drift. In contrast, Sepp & Rakhmonov (2023) show that most conventional SV models do not satisfy the invariance of ℙ-model under the change of measure to ℚ. In the following, we will consider model dynamics under ℚ and drop the hat notation in Eq. (3.10).

3.2. Dynamics under MMA measure

We consider price dynamics with the log-normal beta SV model in Eq. (3.1) under the MMA measure ℚ. The joint dynamics are specified for the spot price St, the instantaneous volatility σt and the QV It under the MMA measure ℚ as follows :

The mean-reversion of the volatility process is specified using the mean level of the volatility 𝜃, 𝜃>0, and the mean-reversion speed which is the linear function of the volatility κ1+κ2σt, κ1≥0,κ2≥0. As a result, the quadratic drift of the volatility process is given by

We introduce the zero-drift stochastic driver Zt, Zt=e−∫t0r(t′)dt′St and its inverse Rt, Rt=Z−1t, with the following dynamics :

Next, we introduce the log of the zero-drift price process Xt=lnZt :

Using XT under Assumption 2.1, we represent the spot price ST by

3.2.1. Properties of log-normal SV process

We establish important properties related to the regularity of the volatility process. We consider the volatility process in model dynamics (3.12) represented as follows :

We notice that the process σt is not a polynomial diffusion, see Filipović & Larsson (2016), Lemma 2.2, because the drift coefficient is a second-order polynomial in σt. Since the process in Eq. (3.19) has super-linearly growing drift, standard results for the uniqueness of strong solution are no longer applicable, see Sec. 5 of Karatzas & Shreve (1991) for details. We will establish the existence of the unique strong solution in Theorem 3.3. We first provide a boundary classification for the volatility process to show that log-normal volatility process σt in dynamics (3.19) cannot reach 0 or explode to +∞, which are important properties of the volatility dynamics. Our proof is based on existence of solutions for general stochastic differential equations (SDEs) with so-called monotonic coefficients, so that it is potentially applicable to wider class of diffusion processes.

Assumption 3.1. We assume that model parameters κ1, κ2, 𝜃, 𝜗 satisfy

Theorem 3.2 (Regularity). Under Assumption 3.1, the boundary points {0,+∞} are unattainable for process σt in SDE (3.19).

Proof. Our proof is based on Feller boundary classification for one-dimensional diffusion processes with technical details given in Sec. A.1. □

Theorem 3.3 (Existence and uniqueness of solution). Under Assumption 3.1, SDE in Eq. (3.19) has the unique strong solution.

Proof. We will refer to following theorem that guarantees the existence and uniqueness of general SDEs with monotonic coefficients.

Theorem 3.4 (Gyöngy & Krylov (1980)). Let at(x):[0,T]×ℝ→ℝ, bt(x):[0,T]×ℝ→ℝ be functions, continuous in x, satisfying following conditions:

| (1) | ∫T0sup|x|≤R(|at(x)|+|bt(x)|2)dt<∞ for any T≥0, R≥0, | ||||||||||||||||

| (2) | for x,y,z∈ℝ such that |x|≤R,|y|≤R,|z|≤R following conditions hold:

| ||||||||||||||||

Then there exists unique solution of the SDE

We show that SDE (3.19), where κ1,κ2,𝜃,𝜗 satisfy (3.20), does indeed satisfy conditions 1–3. We emphasize that the positivity of the process demonstrated in Theorem 3.2 is important. Since in our case at(x)=(κ1+κ2x)(𝜃−x), bt(x)=𝜗x, we get

Using that zero is unattainable boundary and simple inequalities z≤1+z2, z3<0 valid for z>0, we can estimate the right hand side of (3.23) as follows :

Proposition 3.1 (Bounded moments). Assume that κ1𝜃>0, κ2>0 and remaining parameters κ2, 𝜃, 𝜗 satisfy conditions (3.20). Let |p|≥1 and T>0. Then we have

Proof. First we prove a slightly weaker result. □

Proposition 3.2. Assume that κ1𝜃>0, κ2>0 and κ2, 𝜃, 𝜗 satisfy conditions (3.20). Then, for every |p|≥1: supt∈[0,T]𝔼σpt<∞ for any T>0.

Proof. Let us first consider the case p≥1. We use same approach as in Lions & Musiela (2007). Applying Itô’s lemma to σpt, we have

The case p≤−1 is treated similarly: we denote q:=−p≥1 and introduce ˜σt:=σ−1t which is well-defined due to Theorem 3.2. We find that Ũ(τ):=𝔼(˜σqt) solves the problem

Similarly to the proof of Proposition 3.2, we apply Itô’s formula to σpt

We obtain

3.3. Dynamics under inverse measure

First we define the model dynamics (3.12) under the inverse measure ˜ℚ. As a by-product, we show that in SDE (3.26) the quadratic term is important to preserve the functional specification of volatility drift under ˜ℚ.

Theorem 3.5. The dynamics of the volatility σt in (3.12) under ˜ℚ are given by

MMA measure ℚ and inverse measure ˜ℚ are related by the density process

Proof. We consider Rt=Z−1t. Applying Itô’s lemma, we see that Rt satisfies

Using Girsanov’s theorem, we switch to the measure ˜ℚ under which the processes ˜W(0)t and ˜W(1)t defined by ˜W(0)t=W(0)t−∫t0σsds, ˜W(1)t=W(1)t are uncorrelated Brownian motions. Then the dynamics of volatility process σt under ˜ℚ become

We highlight that the idea of using change of measure to study the martingale property is widely used in the literature, see Ruf (2015) and references therein. We now derive sufficient conditions for the equivalence of measures ℚ∼˜ℚ which is required for the application of Girsanov theorem in the proof of Theorem 3.5.

Theorem 3.6. Under Assumption 3.1, measures ℚ and ˜ℚ are equivalent if and only if κ2≥β.

Proof. By Theorem 3.5, the density 𝔼t[d˜ℚ/dℚ]=Zt/Z0. Therefore, the martingale property for Zt under ℚ guarantees equivalence ℚ∼˜ℚ. Using Theorem 3.7(1) concludes the proof. □

Theorem 3.7 (Martingality of Log-normal SV model with quadratic drift). Under Assumption 3.1, the price processes Zt and Rt in Eq. (3.15) for model dynamics (3.12) have following properties:

| (1) | The process Zt is a martingale under the MMA measure ℚ iff κ2≥β. | ||||

| (2) | The process Rt is a martingale under the inverse measure ˜ℚ iff κ2≥2β. | ||||

Proof. (1) Theorem 9.2 in Lewis (2000) or Sin (1998) shows that Zt is ℚ-martingale if and only if the process

(2) According to Theorem 3.5, the dynamics of {σt,Rt} under ˜ℚ become

Using Theorems 2.4(i), 2.4(ii) of Lions & Musiela (2007), Rt is a martingale if

Corollary 3.1 (Martingality of Log-normal SV model with linear drift). For dynamics (3.12) with κ2=0 we obtain the following:

| (1) | The process Zt is martingale under ℚ iff β≤0. | ||||

| (2) | The process Rt is martingale under ˜ℚ iff β≤0. | ||||

Proof. Follows by setting κ2=0 in Theorem 3.7. □

Importantly we conclude that the log-normal SV model with linear drift leads to arbitrages when the return–volatility correlation is positive.

3.4. Joint dynamics of state variables under ℚ and ˜ℚ

We introduce the mean-adjusted volatility process Yt

Corollary 3.2 (Dynamics under the MMA measure ℚ). The joint dynamics of log-price Xt, the mean-adjusted volatility process Yt, and the QV It under the MMA measure ℚ are driven by

Itô’s lemma, applied to Eq. (3.33), yields marginal dynamics of Y under ˜ℚ :

Corollary 3.3 (Dynamics under the inverse measure ℚ̃). The joint dynamics of log-price Xt, the mean-adjusted volatility process Yt, and the QV It under the inverse measure ˜ℚ are driven by

3.5. Steady-state distribution of volatility process

It is important to establish that the steady-state density (SSD) of the volatility process σt in SDE (3.19) exists. The SSD, denoted by G(σ), solves the following ODE :

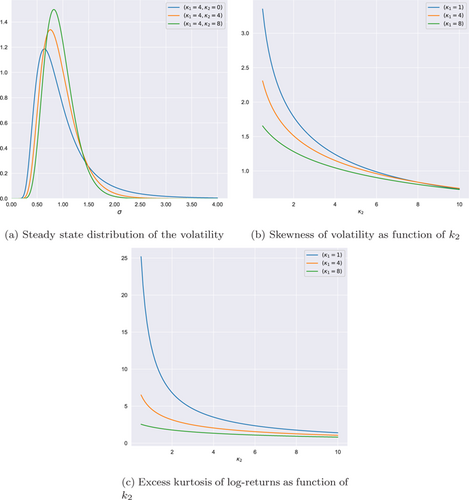

In Fig. 1(a), we show the SSD for the three sets of model parameters. The case (κ1=4,κ2=0) corresponds to the linear mean-reversion; the case (κ1=4,κ2=4) (generally the case with κ2=κ1/𝜃) corresponds to the pure quadratic drift; the case (κ1=4,κ2=8) corresponds to the quadratic drift. The linear model with κ2=0 implies the heavy right tail for the distribution of the volatility. In Fig. 1(b), we show the skewness of the volatility as function of κ2. As κ2 increases, the skewness of the volatility declines.

Fig. 1. (a) The steady state PDF of the volatility computed using Eq. (3.38) with fixed κ1=4 and κ2={0,4,8}. (b) and (c) The skewness of the volatility computed using Eq. (3.39) and the excess kurtosis of the unconditional returns distribution computed using Eq. (3.44), respectively, both as functions of κ2, for the three choices of κ1=1,4,8. Other model parameters are fixed to 𝜃=1 and 𝜗=1.5.

3.5.1. Unconditional distribution of returns

We make an interesting connection between the skewness of the volatility process and the kurtosis of returns distribution. Following Chap. 9 in Barndorff-Nielsen & Shiryaev (2015), we assume that the distribution of returns over period δt is Gaussian conditional on σ :

The unconditional distribution of returns under the SDD of the volatility is

We compute the excess kurtosis of returns distribution using with Eq. (3.39) as follows :

It follows that the kurtosis of the unconditional distribution in Eq. (3.44) is maximal when (). The kurtosis is finite only if liner mean-reversion parameter is higher than the total volatility of variance. The kurtosis declines when rate b () increases. In Fig. 1(c), we show the kurtosis for the three choices of . We see that for the each choice, the parameter can be thought as a dampening parameter to reduce both the skewness of the steady-state PDF of the volatility and the kurtosis of the unconditional PDF of returns.

3.6. Moments of volatility process

Computation of moments for the log-normal SV with the quadratic drift is an open problem with no exact solution. We show that there exists a closed-form solution based on a truncation method, which we further adopt for the affine expansion of the MGF. We consider the mean-adjusted volatility process defined in Eq. (3.32). We define its power function , , and the mth moment, , as follows :

Applying Itô’s lemma to under the dynamics in Eq. (3.33), we obtain

Proposition 3.3 (Moments of volatility process). The solution to moments in Eq. (3.45) can be presented as a matrix equation for an infinite-dimensional vector

An approximate solution to ODEs (3.47) is obtained by truncating the number of terms to and defining a finite dimensional vector of mth moments as follows:

The analytic solution to ODE system (3.48) is given by

Proof. We first present Eq. (3.46) as follows :

Thus, moment solves recursive equation (omitting subscript t)

Using the fact that and we can present Eq. (3.50) for as a matrix equation for infinite-dimensional column vector in Eq. (3.47). Clearly, that under regularity conditions (real parts of eigenvalues of are negative), we must have . Thus, to make a finite-dimensional approximation of Eq. (3.47), we fix and assume

Finally, by substituting fixed values for and , we present (3.47) for finite-dimensional vector of mth moments, , in Eq. (3.48). Solution in Eq. (3.49) is obtained by integration. □

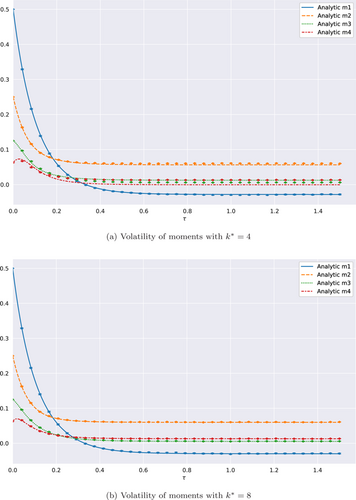

In Fig. 2, we plot first four moments of the volatility process computed using Eq. (3.49) with truncation order (Fig. 2(a)) and (Fig. 2(b)). For comparison, we show estimates and confidence intervals obtained by MC simulations. We see that the low-order truncation with is consistent with MC estimates for the first and second moments. The high-order truncation with is consistent with the first four moments compared to MC estimates.

Fig. 2. The first four moments of mean-adjusted volatility computed using Eq. (3.49) with the truncation order (a) and (b) as functions of . The model parameters , , , . Dots and error bars denote the estimate and 95% confidence interval, respectively, computed using MC simulations of model dynamics using scheme in Eq. (3.59) with number of path equal and daily time steps.

Remark 3.1. We note that if , the system (3.48) becomes lower tridiagonal so that it can be solved exactly for all moments up to by the sequential integration from to .

3.7. Properties of quadratic variance process

We consider the QV process defined by . The QV is an important quantity for option pricing. In particular, the expected QV equals model-based fair value of the continuous-time variance swap, which could be used for model calibration.

Proposition 3.4 (Bounded moments). Under Assumption 3.1 and the QV is well defined under the MMA measure and for any . If then the QV is well defined under the inverse measure and for any .

Proof. As , the first statement follows from Proposition 3.1. The second statement follows using the volatility dynamics under in Eq. (3.28). □

We define the annualized expected QV as follows :

Corollary 3.4 (Expected value). The expected value of the QV using th order truncation in Proposition 3.3 is given by

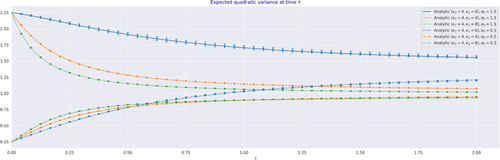

The approximation term includes only the truncation error because Eq. (3.54) is computed analytically using matrix exponentiation. In Fig. 3, we present comparison of the analytical solution for the expected QV using Eq. (3.53) to the estimate and confidence interval based on MC simulations. The truncation-based analytic solution is consistent with MC estimates.

Fig. 3. The expected QV computed using Eq. (3.53) with . The top and bottom three lines correspond to and , respectively. The dot and the error bars denote the estimate and 95% confidence interval computed using MC simulations of model dynamics with scheme in SDE (3.59) with number of path equal and daily time steps. The model cases of mean-reversion correspond to and three choices with other model parameters set to , .

3.8. Monte Carlo discretization

We consider the SDE (3.19) for the volatility process and introduce the log-volatility process . Applying Itô’s formula, we obtain the following dynamics for :

We consider a time horizon and an equidistant time grid , , . Backward Euler–Maruyama (BEM) scheme for is defined by

We prove that SDE (3.56) has a unique solution in in order to make BEM scheme well-defined. Although BEM scheme in Eq. (3.56) cannot be solved analytically in , we still can solve Eq. (3.56) numerically due to the smoothness and monotonicity of function , using just few iterations of Newton algorithm, see Proposition 3.5.

Proposition 3.5. We introduce . Then, for every the equation has a unique solution in .

Proof. As is continuous, and , the result follows. □

Theorem 3.8. Backward Euler–Maruyama scheme for log-volatility process in SDE (3.55) has a strong convergence rate of 1.

Proof. The proof of the theorem is based on Proposition 3 of Alfonsi (2013). We present it in Proposition 3.6.

Proposition 3.6. We fix and assume that

Instead of Eq. (3.57), we prove slightly stronger estimate in Eq. (3.58). The latter follows from the combination of Hölder inequality and Proposition 3.1. We omit straightforward details to obtain

Corollary 3.5. MC discretization scheme of the model dynamics (3.12) under the MMA measure using log-price in SDE (3.16) is given by

We note that the first two dynamics are defined in , which does not require extra handling of boundary conditions, in contrast to some affine models for the variance process.

4. Affine Expansion of Moment Generating Function

We consider the valuation problem of a derivative security with payoff function settled at maturity time T using log-price process defined in Eq. (3.16). We denote current time by t and introduce time-to-maturity variable . We denote the undiscounted value function of this derivative security by .

To solve the general valuation problem under both and , we parametrize the value function using binary parameter p, , respectively, as follows :

Theorem 4.1. The value function solves the following PDE on the domain

Proof. We note that the classic Feynman–Kac formula (for an example, see Sec. A.17 in Musiela & Rutkowski (2009)) cannot be applied directly to Eq. (4.1) because the model dynamics (3.34) and (3.36) do not satisfy the linear growth condition. In Sec. A.2 we prove that the existence and the uniqueness is guaranteed by Theorem A.1. This theorem states that if the covariance matrix of diffusive operator is nonnegative definite and the state variables neither explode nor leave an open domain, then there exists a unique solution to the PDE representation of the conditional expectation under corresponding model dynamics.

Now using the diffusive operators in the valuation PDE (4.2), we obtain that the diffusion matrix a in Eq. (A.14) equals

We now set the domain D of state variables in PDE (4.2) by . As we showed in Theorem (3.2), under the MMA measure (3.34) and the inverse measure (3.36), the boundary points are unattainable for the volatility process , hence solution for mean-adjusted volatility process and QV cannot explode or leave D before T. Same applies to as are unattainable for . Thus, condition 1 of Theorem A.1 is satisfied. As boundedness condition A.1 is satisfied by construction, the statement of Theorem 4.1 follows from Theorem A.1 stated in Sec. A.2. □

4.1. Moment generating function

We introduce the MGF of the three model variables: the log-price , the QV , and the mean-adjusted volatility driver . We extend our analysis using the transform variable in to generalize our solution method for all the three state variables in the model. We denote the MGF by using respective complex-valued transform variables

Using model dynamics (3.34) under the MMA measure and model dynamics (3.36) under the inverse measure, respectively, the MGF solves the following PDE on the domain :

Theorem 4.2. Given the transform variable the MGF of the log-price

Similarly, the MGF of the log-price

Proof. As is -martingale, the result immediately follows from Jensen’s inequality, as the function is convex for . Result for the inverse measure follows analogously. □

Theorem 4.3. Given transform variable the MGF of QV

Proof. We denote which satisfies SDE and set . Feynman–Kac formula allows to recast the solution as the solution of the Cauchy problem

We build a supersolution to (4.7) using the following ansatz :

We show there exists such that

Theorem 4.4. Given the transform variable the MGF of the mean-adjusted volatility process

Proof. We set and consider

Using Feynman–Kac formula we can rewrite as the solution of the Cauchy problem

4.2. Affine expansion

Given that coefficients in PDE (4.6) are nonaffine in state variable Y, the PDE cannot be solved by assuming an exponential affine-solution with a finite number of coefficients. Instead, we can show that the solution to the PDE (4.6) can be represented by an exponential-affine ansatz using an infinite dimensional vector , , as

We note the similarity between the current ansatz (4.13) for problem (4.6) and the problem of computing the moments of the volatility process addressed in Proposition 3.3. There we first represent the recursive solution to the moments as an infinite dimensional vector in Eq. (3.47). We then obtain an approximate solution by a truncation of infinite series and specifying a boundary condition to reduce the problem to a finite-dimensional vector (3.48), which can be solved using analytical methods. Here we follow this insight for solving PDE (4.6) and term our (truncated) solution as the affine expansion for a given order.

4.2.1. First-order expansion

Theorem 4.5 (First-order affine expansion). The MGF in Eq. (4.5) can be decomposed as follows:

The remainder term solves the following PDE (omitting arguments) :

Proof. We take as an ansatz the leading term in decomposition (4.16) and substitute it into the PDE (4.6). To obtain the ODEs (4.17) for , we match terms with , . To obtain the PDE for the remainder term , we account for higher powers of , . Finally, initial conditions for ODEs (4.17) and PDE (4.18) are set to reproduce conditions of Eq. (4.6). □

Proposition 4.1. We take and , . Assuming that hypotheses 1, 2, 3 listed in Theorem 4.7 hold, the continuous solution in Eq. (4.17) exists on .

Proof. The proof is identical to that of Theorem 4.7 for the second-order expansion. We skip it for brevity. □

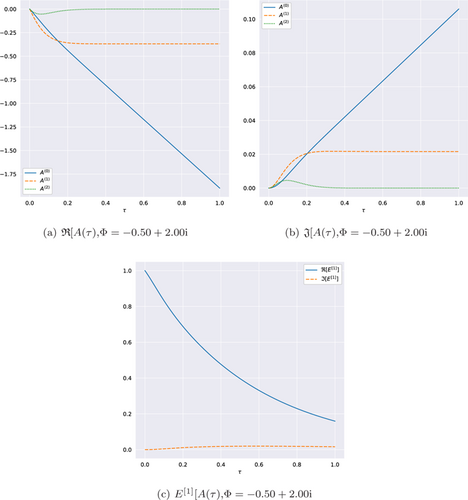

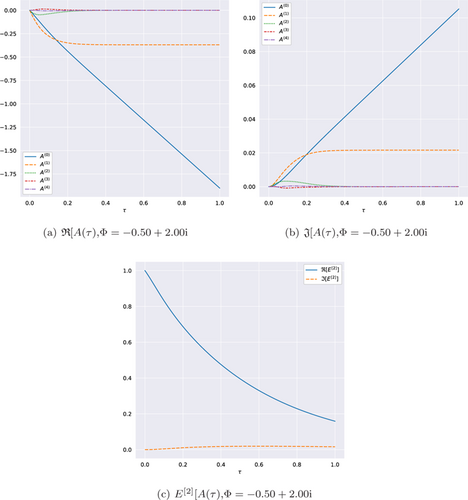

In Fig. 4, we show the real and imaginary parts of ODE solutions and . We see that functions and quickly reach an equilibrium point, while is the nonstationary part which contributes to the leading term .

Fig. 4. The solution of ODEs of the first order expansion in Eq. (4.17) as function of for , . We use the model parameters calibrated to Bitcoin options data and reported in Eq. (6.4). (a) The real part of the solution, (b) the imaginary part of the solution, (c) the the real and imaginary parts of the exponential term in Eq. (4.16).

Corollary 4.1 (Estimate of the first-order remainder term). We obtain the following estimate for the remainder term in Eq. (4.18) :

Proof. The proof is analogous to the second-order expansion in Proposition 4.3. □

Corollary 4.2. First-order affine expansion for the MGF (4.5) is obtained by using the leading term in Eq. (4.15) :

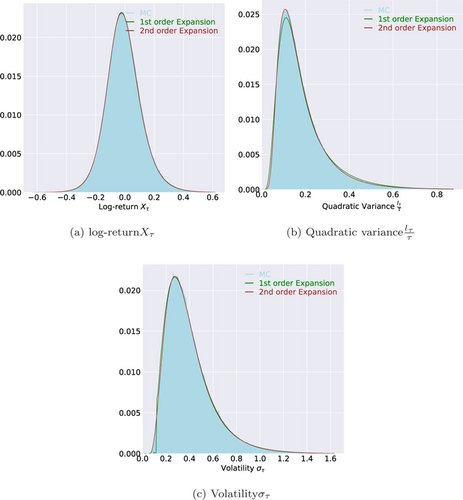

In Fig. 6, we illustrate that the first-order approximation (4.22) for the MGF produces valid and accurate PDFs for all three state variables.

4.2.2. Second-order expansion

Theorem 4.6 (Second-order affine expansion). The MGF in Eq. (4.5) can be decomposed as follows:

The leading term is given by the exponential-affine form

The remainder term solves the following PDE (omitting arguments)

Proof. The proof follows by analogy to the first-order expansion in Theorem 4.5. □

Remark 4.1. We emphasize that sparse matrices in the quadratic term do not depend on the measure parameter p, while the linear and free terms depend on p in ODEs (4.17), (4.25) for the first-and the second-order expansion.

We now present the result on the existence of continuous solution to Eq. (4.25) in Proposition 4.2 and discuss it further in Sec. 4.2.3.

Proposition 4.2. We take and , . Assuming that hypotheses 1,2,3 listed in Theorem 4.7 hold, the continuous solution in Eq. (4.25) exists on .

Proof. See Theorem 4.7. □

In Fig. 5, we show the real and imaginary parts of for the second-order expansion and the leading term . We see that, similarly to the first order expansion illustrated in Fig. 4, functions reach an equilibrium point, while is the nonstationary part which contributes to the leading term . By comparing the low order terms between the first and the second expansions, we notice no visible difference, which suggest that the expansion is rather recursive and higher order terms make insignificant contribution to the low order terms. We also notice that terms and are very small in magnitude compared to the first three terms, which suggest that higher order term only provide a small marginal contribution.

Fig. 5. The solution of ODEs in Eq. (4.25) as function of for , . We use the model parameters calibrated to Bitcoin options data and reported in Eq. (6.4). (a) The real part of the solution, (b) the imaginary part of the solution, (c) the real and imaginary parts of the exponential term in Eq. (4.24).

Corollary 4.3 (Estimate of the second-order remainder term). We obtain the following estimate for the remainder term which solves Eq. (4.26) :

Proof. The formal solution for the remainder term solving problem (4.26) is obtained by applying the Feynman–Kac formula and is given by

Corollary 4.4. Second-order affine expansion for the MGF (4.5) is obtained by using the leading term in Eq. (4.24) as

In Fig. 6, we illustrate that the second-order approximation (4.31) for the MGF produces valid and accurate PDFs for all three state variables.

4.2.3. Solution of quadratic differential systems

It is established that the global existence problem for the solution of quadratic differential systems is nontrivial, see Coppel (1966), Dickson & Perko (1970), Jacobson (1977), Baris et al. (2008) among others. We can show that the matrices of quadratic terms in Eqs. (4.17) and (4.25) are indefinite because their eigenvalues are of both signs. Thus, we can provide a result for global existence that is only conditional by nature. We focus on important case of option valuation on underlying assets with , , and .

Dickson & Perko (1970) show that complex-valued solution of quadratic ODEs such as in Eq. (4.17) or Eq. (4.25) has maximal interval of existence , where denotes its blow-up time.

Fig. 6. PDFs computed using the inversion of the first order expansion term in Eq. (4.16) and the second-order expansion term in Eq. (4.24) for the state variables under the MMA measure: (a)–(c) PDFs of log-return, , of QV normalized by , , of volatility , , respectively. We use the model parameters for Bitcoin options reported in Eq. (6.4) with time to maturity of one month, . The blue histogram is computed using realizations from MC simulations of joint model dynamics (3.12) using scheme in Eq. (3.59) with the number of path equal 400,000 and daily time steps.

Theorem 4.7. Assume following conditions are satisfied:

| (1) | i.e. real part of cannot blow up before . | ||||

| (2) | as i.e. leading term of the affine expansion does not vanish as we approach blow-up time when transform variable is real. | ||||

| (3) | i.e. remainder term is uniformly bounded from below. | ||||

If MGF in Eq. (4.6) is finite with then continuous solution of Eq. (4.17) and of Eq. (4.25) exists on .

Proof. See Sec. A.4. □

By Theorem 4.7, we obtain that continuous solution for the first-and second-order affine expansions in Eqs. (4.16) and (4.24), respectively, exists on if 1, 2, 3 hold.

4.3. Properties of affine expansions

We now consider the key properties of the affine expansion of the MGF. For brevity, we focus on the properties of the second-order expansion, which is our key development. For the first order expansion, martingale conditions stated in Proposition 4.3 hold, and the consistency with the expected values (but not with their variances) of three state variables is ascertained in the same way as for the second-order expansion.

Proposition 4.3 (Martingale conditions). Assuming that hypotheses 1, 2, 3 in Theorem4.7 hold, the second-order expansion of the MGF in (4.31) with defined in Eq. (4.24) satisfies the martingale conditions for log-return

Proof. For , we obtain in (4.25). Given zero initial conditions, due to the uniqueness of the solution. Similarly, for and , we obtain that , hence . Similarly, for and we obtain that , hence . □

Proposition 4.4 (Volatility moments). The MGF in Eq. (4.31) with the second-order affine term in (4.24) reproduces exactly the expected value and the variance of the volatility for .

Proposition 4.5 (Log-price moments). The MGF in Eq. (4.31) with the second-order affine term reproduces exactly the expected value and the variance of the log-price for .

Proposition 4.6 (QV moments). The MGF in Eq. (4.31) with the second-order affine term reproduces exactly the expected value and the variance of QV for .

Proof. Propositions 4.4 and 4.5 are proved in Secs. A.3.1 and A.3.2, respectively. Proof of Proposition 4.6 is similar to the proof of Proposition 4.5. □

Remark 4.2. In Remark 3.1 we noted that the system of volatility moments (3.48) is solved exactly for , otherwise the solution is approximate. Thus, we cannot generalize above statements for . However, it is our hypothesis that moments obtained using (4.24) correspond to moments computed in (3.48) using truncation order and that truncation error as function of is very small.

In Fig. 6, we show PDFs computed using the inversion of first-order solution in Eq. (4.16) and second-order solution in Eq. (4.24) for the three state variables in model dynamics (3.34). The blue histogram is computed using MC simulations of the joint model dynamics. We see that both first-and second-order expansions produce valid PDFs and match consistently histograms produced by the MC simulations. The first-order expansion may not be very accurate for the QV and the volatility variables because it is not consistent with variances of these variables. The second-order expansion is consistent with variances and co-variances of all state variables and it accurately matches PDFs computed using MC simulations.

5. Option Valuation

We apply the zero-drift log-price process in Eq. (3.16) and Eqs. (3.17) and (3.18) for spot and futures prices, respectively, to consider option valuation on both spot and futures underlyings. We denote by the price of either spot or futures asset

As we conclude in Corollaries 4.2 and 4.4, we apply affine expansion given by either the first order in Eq. (4.16) or the second order in Eq. (4.24) as analytic solutions to the MGF under the dynamics (3.16). Given that the MFG is available analytically, we then apply Lewis–Lipton approach for valuation of vanilla options using Fourier transform, see Lewis (2000), Lipton (2001, 2002).

5.1. Vanilla calls and puts

Using Eq. (5.1), we represent put and call payoff functions for strike price K using capped payoff by

Proposition 5.1. The valuation formula for capped payoff is given by

Proof. Using affine expansion for MGF G with either first-order in Eq. (4.22) or second-order in Eq. (4.31), the PDF of is computed by Fourier inversion

For valuation problem in Eq. (5.3), we obtain

Assuming that inner integrals are finite, we exchange the integration order as

As a result, calls and puts on spot underlying are valued using Eqs. (5.2)

We emphasize that in valuation equations (5.9) we implicitly assume that the price process , , is -martingale under the MMA measure, otherwise formulas (5.9) are not valid. For that we need a restriction , see Theorem 3.7.

5.2. Inverse calls and puts

Using generic price process of underlying spot and futures given in Eq. (5.1), we represent the payoffs of inverse calls and puts by

Proposition 5.2. The valuation formula (5.6) for the inverse capped payoff becomes

Proof. As in Eq. (5.7), we compute the transform of the inverse capped option

As a result, calls and puts are valued using capped payoff (5.12) :

Hereby, we need to compute

5.3. Options on quadratic variance

We consider a call option on QV with the payoff function

Proposition 5.3. The value of the call option on the QV under is given by

Proof. Consider an option on QV with terminal payoff . Using Sepp (2008), we find that option value is given by Eq. (5.20), where is the transformed payoff function

For a call option on QV with strike K, provided , Eq. (5.22) becomes

Sepp (2008) derives transforms for typical payoff on the QV including puts and calls on the square root of the QV. Assuming that the inverse measure is a martingale measure for generic spot and futures underlying defined in Eq. (5.1), the inverse option on the QV is given under by

Proposition 5.4. The value of the call option on the QV under the inverse measure is given by

Proof. Using affine expansion for MGF G with either first-order in Eq. (4.22) or second-order in Eq. (4.31), we compute the joint density of using inverse Fourier transform by

As a result, we obtain

Exchanging the integration order, we have

6. Model Implementation and Calibration to Options Data

6.1. Implementation

In practical applications, either for model calibration or for options valuation, we need to compute call and put option prices on a grid consisting of several maturities and strikes, also referred to as an option chain. We consider grid with M maturities and J strikes. For option valuation using the MGF, we apply the affine expansion given by either the first order in Eq. (4.16) or the second order in Eq. (4.24).

First, we fix the space grid with size P (typically, ) of transform variable for the log-price. We solve the system of ODEs numerically for either the first-order expansion in Eq. (4.16) or for the second-order expansion in Eq. (4.24) in time up to the last maturity time. The computational cost of this step is

Second, we compute values of the MGF on the grid of for each maturity slice. We then compute values of capped payoffs for the MMA measure in Eq. (5.4) or for the inverse measure in Eq. (5.13) using Simpson rule for numerical integration. We then value all options in a given chain. The computational cost of this step is

The main difference with numerical implementation of affine models is that the first step can be computed with cost close to because the solution to the MGF can be computed analytically without solving ODEs numerically. The cost ratio between the implementation of the log-normal SV model and an affine SV model compares favorably when the number of maturities becomes large with M close to , and when the number of strikes J becomes large as well.

6.2. Model calibration

To illustrate that the log-normal SV model can handle different market regimes, we use time series of option prices on Bitcoin observed on Deribit exchange from April 2019 to October 2023. We focus on short-dated options with expiries including one and two weeks and one month, because these are the most liquid and actively traded expiries. We use time series of options chains traded on Deribit. We fix calibration every week with option prices samples each Friday at 10:00 UTC. We include puts and calls with absolute values of option deltas between and , respectively.

For the stability of calibration, we estimate mean-reversion parameters and beforehand. The reason is that mean-reversion parameters and volatility-of-volatility with volatility beta are co-dependent so that it is possible to produce similar smiles and skews using different values of these parameters. We follow the procedure in Sepp & Rakhmonov (2023) for estimation of parameters and by fitting the model implied auto-correlation of the log-normal volatility process to the empirical auto-correlation. This is efficient because the model auto-correlation function is determined solely by mean-reversion parameters. The estimated values of and are the following and , which are kept fixed through the entire period (in practice we would adjust these estimate regularly using most recent data).

Thus, we need to estimate four model parameters . Parameters and control the level and the slope of at-the-money (ATM) implied volatilities, and and control the skewness and the convexity of implied volatilities, respectively. We apply a stronger constraint that guarantees martingale property for the inverse process under using Theorem 3.7. To compute model prices we apply the second-order affine expansion in Eq. (5.9). For each set of sampled option prices, we minimize the weighted mean squared error (WMSE) between model implied volatilities, , and market mid-point implied volatilities, , where K and T are option’s strike and maturity, respectively, as followsd :

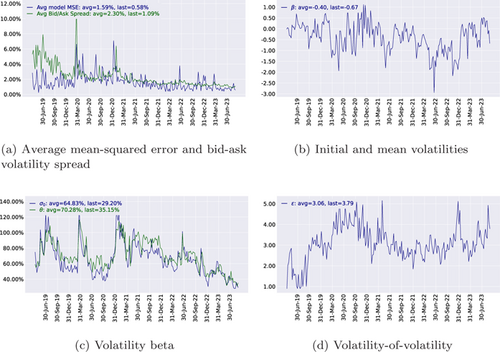

In Fig. 7(a), we show the time series with the quality of the model fit which is computed using the square root of average squared differences between model and market implied volatilities. As a benchmark, we show the average spread between implied volatilities of ask and bid quotes for options in the calibration set. We observe that most of the times, the average model mis-pricing is within the average bid-ask spread. We see that year 2020 of COVID-19 pandemic is characterized by high volatility and high spreads, yet the model is able to fit these markets well. In recent years of 2022 and 2023, bid-ask spreads declined while the model error (the average difference between market and model implied volatility) became less than most of the times.

Fig. 7. Time series of the quality of the model calibration and of calibrated model parameters using weekly model calibrations to prices of option on Bitcoin traded on Deribit exchange from April 2019 to October 2023. (a) Time series of the mean squared error (MSE) between model and market implied volatilities and the average bid-ask (Bid/Ask) spread of quoted implied volatilities. (b)–(d) Time series of estimated initial volatility and mean volatility , volatility beta , and volatility-of-volatility , respectively.

In Figs. 7(b)–7(d), we show the time series of calibrated values of initial volatility and mean volatility , volatility beta , and volatility-of-volatility , respectively. We observe downward trend in the level of implied volatility, falling from average levels of in years 2021 and 2022 to most recent averages of about . At the same time, volatility beta and volatility-of-volatility remain range bound suggesting than relative value of calls and puts is intact despite falling level of the overall volatility. The volatility beta fluctuates between positive and negative values most of the times following the market sentiment. When the sentiment is bullish, calls are bid and volatility beta becomes positive and, vice versa, during bearish sentiment, puts are bid and the volatility beta becomes negative. Thus, as we discuss in Sec. 3.3, the conventional SV models may not be arbitrage-free for the valuation of options on cryptocurrencies when return–volatility correlation become positive.

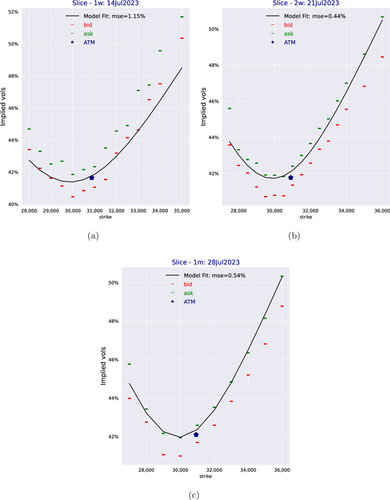

In Fig. 8, we show the quality of model fit to Bitcoin options traded on Deribit exchange on 20 June 2023. On this day, fitted model parameters are the following :

Fig. 8. Quality of model fit to Bitcoin options on 20 June 2023 reported in Eq. (6.4) using the three most liquid slices: one week (a), two weeks (b), one month (c). Continuous black line is model implied volatilities computed using the second-order affine expansion in Eqs. (5.9) and (5.16). Bid and ask displays the market bid and ask quotes, the ATM is the ATM mid-point volatility. Model implied volatility is displayed using the continuous black line. MSE is the mean squared error between the model and the mid of market bid-ask volatilities.

In Fig. 8, we show the quality of model fit on this date. We observe positive skewness of implied volatilities, which results in positive volatility beta. Continuous black line shows model implied volatilities computed using the second-order affine expansion in Eq. (5.9). Bid and ask displays the market bid and ask quotes, the ATM is the ATM mid-point volatility. MSE denotes the mean squared error between the model implied volatilities and the mid of market bid-ask implied volatilities. We see that the log-normal SV model calibrated to Bitcoin options is able to capture the market implied skew very well across most liquid maturities with only four parameters. The average MSE is about for longer maturities, which is within the bid-ask spread. Calibration to the ATM region can be further improved using a term structure of the mean volatility . In a practical setting, the SV model dynamics can be augmented with a local volatility (Lipton (2002)) to accurately fit the implied volatility surface.

6.3. Comparison of valuation under MMA and inverse measures

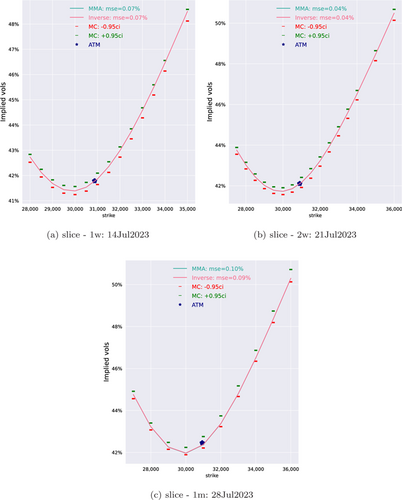

Since Bitcoin options, which are traded on the Deribit exchange, have inverse payoffs, it is important that there is no-arbitrage between the MMA and the inverse measures. In Fig. 9, we compare the model implied volatilities computed from prices of vanilla and inverse options valued under the MMA and inverse measures, respectively. We use the second-order affine expansion with model parameters reported in Eq. (6.4) for computing model implied volatilities for the same maturities as in Fig. 8. As benchmark, we use the MC simulation of the model dynamics (3.12) using scheme in Eq. (3.59) with the number of paths equal and daily time steps. We show the 95% confidence interval of MC estimates as dashed lines like bid/ask lines

Fig. 9. Implied volatilities of Bitcoin options which correspond to the slices used in model calibration and a uniform range of strikes and which are computed using model parameters reported in Eq. (6.4) under the MMA measure (MMA) and the inverse measure (Inverse). Continuous aqua and pink lines show model implied volatilities computed using the second-order affine expansion in Eqs. (5.9) and (5.16), respectively. Dashed lines labeled by and are MC 95% confidence intervals computed using scheme in Eq. (3.59) with number of path equal and daily time steps. MSE is the mean squared error between BSM volatilities inferred from model values and the MC estimates.

We observe that option values computed using the second order affine expansion under the MMA and inverse measures are very close to each other with the differences being within the numerical accuracy of an ODE solver and Fourier inversion (of order ). The difference in terms of implied volatilities does not exceed .

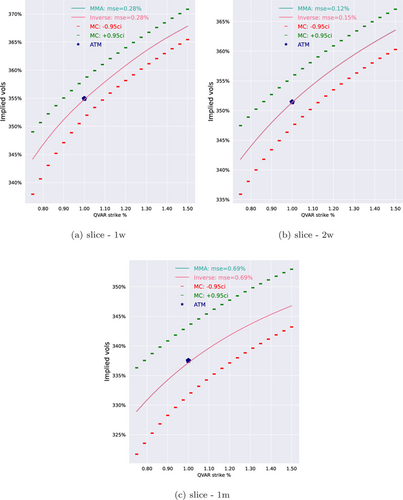

In Fig. 10, we show model prices of call options on the QV computed using the second-order affine expansion under the MMA and inverse measures, and the comparison with MC estimates. We use the same expiries as for the model calibration and the same parameters reported in Eq. (6.4). We also observe that the solution under the both measures are consistent and agree with MC simulations. Interestingly, we observe that the implied volatility skew of options on the QV is upward sloping, which is observed in market data of options on the QV and listed options on VIX index. It is known that Heston model, even augmented with jumps, produces downward sloping skews on options on the QV (see for an example Drimus (2012) and Sepp (2012)). As a result, the log-normal SV model implies realistic patterns of implied volatility-of-volatility.

Fig. 10. Implied volatilities of call options on QV of Bitcoin using model parameters in Eq. (6.4) and for the same maturities as in model calibration in Fig. 8. We use the valuation under the MMA measure (MMA) and the inverse measure (Inverse). BSM volatilities are implied from model prices using expected QV computed using Eq. (3.53). Continuous aqua and pink lines show model implied volatilities computed using the second-order affine expansion under MMA measure in Eq. (5.20) and under inverse measure in (5.24), respectively. Dashed lines labeled by and are MC 95% confidence intervals computed using scheme in Eq. (3.59) with number of path equal and daily time steps. MSE is the mean squared error between BSM volatilities inferred from model values and the MC estimates.

7. Conclusion

We have considered the log-normal SV model with the quadratic drift which plays an important role for the existence of martingale measures. We have shown that the log-normal volatility process has the strong solution in spite of having quadratic drift. We have derived admissible bounds of model parameters for the existence of both the MMA measure and the inverse measures. Based on that, we applied proposed SV model for modeling implied volatility surfaces of assets with positive return–volatility correlation.

Since the log-normal SV model is not affine, there is no analytical solution for the MGF in this model. To circumvent this, we have developed an affine expansion approach under which the joint MGF of three state variables (log-price, the QV, and the volatility) is decomposed into a leading term, which has exponential-affine form, and a residual term, whose estimate depends on the higher order moments of the volatility process. We have proved that the second-order leading term is consistent with the expected values and the variances of the state variables. We have applied Fourier inversion techniques for valuation of vanilla and inverse options on spot and futures underlying. By comparison of model values computed using our method with estimates obtained from MC simulations, we have shown that the second-order leading term is very accurate for option valuation. We have demonstrated that our model fits implied volatilities of assets with positive return–volatility correlation. We have shown that the log-normal SV model fits well different market regimes by calibrating model parameters to time series of options on Bitcoin for the past four years.

We have derived backward Euler–Maruyama scheme for discretization of the log-volatility process and show that it has a strong convergence rate of 1. Proposed scheme for the simulation of the log-normal SV model is robust, computationally efficient and does not require any special treatment in discretization.

As an extension of the frameworke we shall consider the applications to the rough SV models proposed by Gatheral et al. (2018) using log-normal volatility. We shall also consider a path-dependent model of the log-normal volatility following approaches in Guyon & Lekeufack (2023) and Lipton and Reghai (2023).f

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Vladimir Lucic for valuable insights and comments. We thank Alan Lewis, Johannes Muhle-Karbe, Blanka Horvath, Kalev Pärna and participants at Imperial College Finance and Stochastics Seminar, TU Munich Oberseminar, ETH Seminar, EAJ Conference 2022 in Tartu for useful discussion and comments. We are grateful for anonymous referees for helpful comments.

Notes

a Github project https://github.com/ArturSepp/StochVolModels provides Python code with the implementation of option valuation using the affine expansion and examples of model calibration to implied volatility data applied in this paper.

b Exp-OU SV models are studied in Fouque et al. (2000), Detemple & Osakwe (2000), Masoliver & Perelló (2006), Perelló et al. (2008), Muhle-Karbe et al. (2022), Drimus (2012). Exp-OU SV models are widespread in industry as a basis for local SV models (Lipton (2002)), see Bergomi (2015), Bühler (2006), Ren et al. (2007), Henry-Labordère (2009), Bergomi & Guyon (2012).

c Such linear specification is the simplest functional form that allows to establish simple relationship between gains on a delta-hedged option portfolio and level of the market volatility. As shown in Bakshi & Kapadia (2003), such form allows to get precise information about the sign and strength of the risk premium.

d We apply scipy implementation of Sequential Least Squares Programming (SLSQP) algorithm.

e Sepp & Rakhmonov (2023a) apply the developed solution for modeling of SV in Cheyette-type interest rate model and obtain closed-form solution for valuation of swaptions under this model.

f The volatility beta is an interesting variable to make path-dependent as well. We observe that in many markets the implied options skewness follows most recent price performance. For example, in options on Bitcoin, the skewness implied from option prices becomes positive following strong performance of Bitcoin.

Appendix A. Proofs

A.1. Proof of Theorem 3.2

We consider the interval and define the scale function and its density, denoted by and , respectively, as follows (see Chap. IV.15 in Borodin (2017)) :

Choosing c such that and setting , we obtain

Now we show that boundary is unattainable. We define , by

We note that the right hand side of (A.6) is finite if and only if

We see that is finite for all . Using asymptotics of incomplete gamma function (see Eq. (6.5.32) in Abramowitz & Stegun (1972)), we obtain for

Substituting asymptotic expansion (A.9) into Eqs. (A.8) and (A.7), we have

We conclude that . Hence, boundary is unattainable. Next, we show that boundary is unattainable as well. By definition of

Substituting Eq. (A.12) into Eqs. (A.11) and (A.10), we have for

A.2. Proof of Theorem 4.1

We provide a version of Feynman–Kac formula in general multidimensional setting, building on results in Heath & Schweizer (2000). Let be a fixed time horizon and D be a domain in . We consider Cauchy problem

We assume that matrix is nonnegative definite for every t. Under certain restrictions on the coefficients of operator and growth conditions on , it is possible to represent the solution of (A.13) by means of conditional expectation known as a Feynman–Kac formula. However, standard results require uniform ellipticity of the operator , see Friedman (1975), which is not satisfied in our case, because the QV is degenerate. Thus, problem (A.13) becomes degenerate parabolic one.

We consider the multi-dimensional SDE

Theorem A.1 (Existence). Suppose that following conditions hold:

| (1) | Solution X of (A.15) neither explodes nor leaves D before T. | ||||

| (2) | is bounded in D. | ||||

Let be the solution of problem (A.13). Then for any .

Proof. Consider sequence of bounded domains contained in D such that and . We fix and find n such that . Let , denote exit time from domains D and . By Itô’s formula

As domain is bounded and , we have

We show that . Using Markov inequality and estimate from Karatzas & Shreve (1991), p. 306 :

Thus a.s. It implies that is bounded by the maximum principle. Finally, by the dominated convergence theorem :

A.3. Consistency of moment for second-order affine expansion

We apply the following lemma relating moments to derivatives of MGF.

Lemma A.1. The MGF defined by the following equation:

Corollary A.1. Given that MGF assumes an exponential-affine form

A.3.1. Proof of Proposition 4.4

We set in the second-order expansion in Proposition 4.4 and suppress arguments for brevity. We consider in Eq. (4.26). Differentiating it w.r.t. , we see that remainder term solves the following problem :

Calculating and taking into account conditions (A.23) at

Using condition , we simplify problem (A.22) at :

We see that when . Hence, second order decomposition is consistent with expected value of for .

To prove the consistency for variance, we first differentiate (4.25) w.r.t. to obtain that solve the system of ODEs (A.26) at as functions of .

We verify that last two functions in solution of Eq. (A.26) are zero for :

Now, taking the second derivative w.r.t. in (4.26), we obtain for

We note that following straightforward relationships are valid :

Combining Eqs. (A.28), (A.24), and (A.29), we simplify Eq. (A.25) at :

A.3.2. Proof of Proposition 4.5

We proceed as in Proposition 4.4. We set and consider the remainder term in (4.26). Differentiating it w.r.t. , we see that solves following problem :

Differentiating w.r.t. and considering (A.32) at , we find

Due to condition , we simplify Eq. (A.31) at as

We see that when . Hence, the second-order expansion term is consistent with the expected value of for .

To show that the second-order expansion reproduces the variance of the log-price, we differentiate Eq. (4.25) with respect to and find that solve the system of ODEs (A.35) at as functions of :

Now, taking the second derivative in (4.26) w.r.t. , we obtain for

Calculating in (4.27) and taking into account boundary conditions (A.32) at , we find that

Combining conditions (A.38), (A.33), and (A.39), we are able to simplify problem (A.34) at as follows :

A.4. Proof of Theorem 4.7

We consider following system of d nonlinear ODEs :

We combine d nonlinear ODEs in (A.41) into single (nonlinear) vector ODE :

Lemma A.2. There exists finite and nonnegative function g such that

Proof. The proof is essentially contained in Keller-Ressel & Mayerhofer (2015) and based on the application of Gronwall’s inequality. □

Lemma A.3. Assume that following conditions are satisfied:

| (1) | when is a real vector, | ||||

| (2) | is zero matrix when is a real vector, | ||||

| (3) | zero initial condition . | ||||

Then solution of system (A.42) remains real for real .

Proof. The proof is available upon request. □

We now consider the problem of continuity of solutions of quadratic differential systems arising in option valuation problem. It is important to highlight that linear and free terms satisfy assumptions of Lemma (A.3) when we set and restrict , for pricing vanilla options under MMA measure. We use same argument for the inverse options when we set and restrict , . We omit straightforward calculations.

We use and to denote blow-up times and when and .

Theorem 4.7. We assume first that . We denote

We set . Then assumption (A.45) implies that . On the one hand

Thus, we obtain

Now, we let be complex. Due to assumption 4.7 and Lemma A.2, we have Repeating the first part of the proof for , leads to (A.48), so that Hence, solution must remain continuous on . □

ORCID

Artur Sepp  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7038-1748

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7038-1748

Parviz Rakhmonov  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9571-7378

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9571-7378