FROM CONCEPTUALISATION TO INDUSTRIALISATION – UNCOVERING THE INTRINSIC NATURE OF PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT OF NON-ASSEMBLED PRODUCTS

Abstract

Using a survey mode of inquiry, involving informants from 19global manufacturing companies in six sectors of the process industries, this study explores the intrinsic nature of product innovation of non-assembled products. Results show that the characteristics of the “transformation-based” production system in the process industries should not only govern the design of the total product innovation work process and the selection and use of related experimental environment but will also influence the design of the forthcoming production system. It is noted that pilot-planting and full-scale production trials are important instruments not only during the product development phase, but also afterward in solving B2B customers’ post-launch production problems. It is concluded that the experimental output from the product development phase of the product innovation work process for non-assembled products is both a new product design and a new foundation for the production process design.

Introduction

The cluster of process industries forms a large portion of all manufacturing industries and accommodates several industrial sectors: Mining and Metals, Mineral and Materials, Chemicals and Petrochemicals, Pulp and Paper, Food and Beverages, Generic Pharmaceuticals, and Steel and Utilities (Lager, 2017a). An important difference between companies in the process industries and in assembly-based industries (Frishammar et al., 2012a) is that supplied and delivered products in the process industries are materials rather than components, a fact which affects not only the upstream supply chain of incoming materials (Lager, 2017b) but also the downstream supply chain of outgoing products (Lager and Blanco, 2010). Strong collaboration with dependency on equipment suppliers (Lager and Frishammar, 2010), raw material suppliers, and technology suppliers has a long tradition in the process industries (Aylen, 2010), and companies in the process industries today rarely develop and manufacture new kinds of process equipment (Hutcheson et al., 1995). If a company relies on captive (company-owned) raw materials, the characteristics of incoming materials will predispose the selection of unit processes and the production system design (Samuelsson et al., 2016) but may also influence certain finished product properties (Linton and Walsh, 2008b). For formal definitions of the process industries, see Appendix A. The manufacturing process in assembly-based industries generally commences with a large number of components that are further reconfigured in a stepwise assembly process into a finished product in which many of the individual components are still traceable (Lager, 2017a; Floyd, 2010). In essence, in an “assembly-based” production system, the product, to a great extent, defines the production process. In consequence, even if product design for processability (Boothroyd et al., 1994) is of utmost importance, product development is a precursor to the final design of the production system. In contrast, the manufacturing of products in the process industries is a stepwise transformation process, in which a few incoming raw materials and ingredients are gradually transformed into many relatively homogenous finished products (Flapper et al., 2002; Dennis and Meredith, 2000). In essence, in a “transformation-based” production system, the production process, to a great extent, defines the product. In consequence, product development in the process industries is in reality the development of a new or improved production process.

In the process industries, integration of product and process innovation is usually vital for strong innovation performance (Lager, 2002), and Etinne (1981) discovered early on that the innovation of new products is more related to the innovation of a new production process, as confirmed by Hullova et al. (2016). Thus, Reichstein and Salter (2006) recommended that product and process innovation should be regarded as “siblings” rather than “distant cousins” (Ballot et al., 2015). The notion that products and inherent product properties in the process industries gradually emerge during an intermittent or continuous transformation process with no direct manual interaction (Floyd, 2010) is reflected in statements like “the process is the product” (Rousselle, 2012) and “the process embodies the product” (Lager and Simms, 2020). The chain of activities from product ideation to product concept development to product design is thus in reality associated with the chain of activities from process ideation to process concept development to final process design. Furthermore, whilst a new or improved product in assembly-based industries is transferred from the R&D organisation to the manufacturing organisation, when a product design is ready after prototyping (Lakemond et al., 2013), the design of new or improved non-assembled products in the process industries takes place in production-oriented experimental environments like laboratories and pilot plants (Frishammar et al., 2014a). The instruments in use for such development activities are thus basically experimental facilities that try to mimic and simulate (physically or theoretically) such production processes and set-ups. Development of prototypes in assembly-based industries is thus displaced by pilot-planting or full-scale production in the process industries, when operating process conditions are established and test batches are produced (Lager, 2000; Pisano, 1997). Pilot and demonstration plants thus bridge knowledge generation in the laboratories and industrial application in production systems (Frishammar et al., 2014a).

For companies in the process industries, as suppliers of functional products, commodities, or both, product innovation or renovation is not only of strategic importance for survival during changing market conditions but also a means to further incorporate urgent sustainability perspectives (Dyllick and Rost, 2017; Johansson, 2006) and accommodate sectoral convergences (Bröring, 2010; Kohut et al., 2020). Thus, a continually renewed and customised work process adapted to companies’ particular operational and product-market conditions, driving innovation and delivery of new or improved products on the market, constitutes a vital dynamic capability (Teece, 2009). In contrast to product innovation in assembly-based industries, the configuration of the production system in product innovation in the process industries begins during the early phases of the innovation work process. Thus, not only is the “experimental environment” for product innovation vastly different in a process-industrial context, but also the idiosyncratic conditions for innovation should incentivise the design of a product innovation work process adapted to such conditions.

The purpose of this study is to further explore and uncover this intrinsic nature of product innovation of non-assembled products and its consequences in the design of the “product development” phase of a product innovation work process, thus furthering the understanding of product and process design during the “development phase” between conceptualisation and industrialisation. In the movement of product and process concepts from conceptualisation to industrialisation, careful consideration and balancing of alternative product development routes are essential, from simulation and laboratory test work to tests in production plants, pilot-planting, or even the erection of a demo plant. Thus, a product innovation work process for non-assembled products not only must be adapted to process-industrial intrinsic conditions for innovation (Lager, 2017a) but also, in an inclusive operational mode, must consider the interrelationship between product innovation and the development of interdependent process technology. This exploratory study constitutes one “key research area” within a broader research project focusing on innovation work processes for non-assembled products in the process industries (Lager and Simms, 2023). Following the general research question for the overall project — What are the main building blocks, incorporated concepts and related constructs of a generic “structural process model” intended to serve as a guiding template for company design or reconfiguration of a formal innovation work process for the development of non-assembled products? — this study addresses the following research questions:

| RQ1: | How are the activities in the “product development phase” of a product innovation work process influenced by the perspective of the process industries as a “transformation-based” cluster of industries? | ||||

| RQ2: | What sort of alternative experimental environments and instruments are currently utilised and recommended to be deployed in the process industries during the “product development phase” of an enhanced innovation work process for non-assembled products? | ||||

| RQ3: | Which aspects on product and process design are of importance to consider during the product development phase of the product innovation work process for non-assembled products in the process industries? | ||||

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. In the following section, a generic “structural process model” is introduced together with the development of a conceptual framework for the study. Next, the research design is presented, including the selection of case–companies and the research instrument. Then, the empirical findings are presented and analysed, and further development of the results is discussed together with management implications. Research contributions and limitations are then presented. Finally, conclusions and suggestions for further research are presented.

Frame of Reference

Introduction of a generic “structural process model” for the development of non-assembled products in “transformation-based industries” as a point of departure for this study

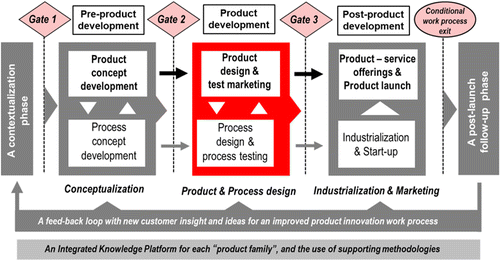

In a previous part of this research project, a theoretical model was developed (Lager and Simms, 2020), depicting a five-stage generic “structural process model” of the innovation work process for non-assembled products. The theoretical model has been further developed and refined in this research project (see Fig. 1), and the model includes three building blocks, Pre-product development, Product development, and Post-product development, which are preceded by a “Contextualization phase” and complemented by a “Follow-up phase” (Lager and Simms, 2023). The outcomes from Contextualisation and Pre-product development, when new product ideas are aligned with corporate product innovation strategy and the existing product portfolio, are well-defined product and process concepts (Lager et al., 2023). The final stage of the product development process is a transfer of the product development results into the “Post-product development” phase, including the activities of industrialisation and the development of product-service offerings (Lager and Storm, in press). The deployment of innovation methodologies as supporting instruments for the product innovation work process has also been further explored and clarified (Lager and Fundin, 2023a, 2023b).

From conceptualization in the pre-product development phase to industrialization in the post-product innovation phase of a formal product innovation work process, the integration of product design and process design is depicted in an iterative fashion. The product development phase contains the two related activities of “Product design & test marketing” and “Process design & process testing”. Consequently, further development of a product concept into a final product design, which is this study’s focus, actually requires the complementary development of an associated process concept into a final process design.

Fig. 1. A slightly modified generic “structural process model” of the product innovation work process in the development of non-assembled products in the process industries (Lager and Simms, 2023); the topical area for this study is depicted in red.

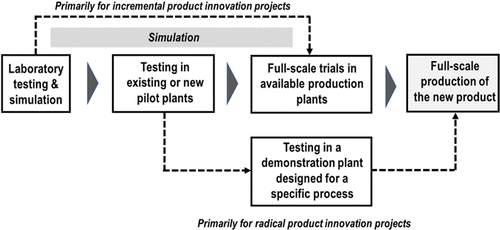

The experimental environment in the development of non-assembled products

In reference to Fig. 2, product innovation in the process industries usually begins with test work in the laboratory (Lager, 2000), which nowadays may be combined with process simulation (Lager and Simms, 2020). Laboratory testing and simulation are activities that, during the Pre-product development phase, are the primary instruments in the development of a product concept and related process concept. In order to get quick feedback on product processability in an operational environment, test work in existing production set-ups is rather common today. However, finding a proper balance between rapid process innovation in the use of production plants while minimising operational disturbances is an important organisational task in the process industries (Bergfors and Lager, 2011; Trott and Simms, 2017). Scaling up experimental results from laboratory test work is sometimes difficult in the process industries (Linton and Walsh, 2008a), because new product characteristics sometimes are added, while existing ones disappear, when product concepts are transferred into an operational environment.

Fig. 2. A simplified dynamic model of different experimental environments in the development of non-assembled products in the process industries.

During the Product Development phase, further test work is primarily carried out in the form of trials in available production plants or pilot plants (company-owned, customer-owned, or operated by another external organisation), depending on the availability of production plant trial time and accessibility of a suitable pilot-plant facility. In radical product innovation requiring interdependent process configurations of high complexity, it is sometimes necessary to finalise product and process design in a demonstration plant. (Hellsmark et al., 2016). However, the use of a demonstration plant is not a replacement for pilot planting but, rather, an instrument to test material wear, develop systems for process control, or manufacture large samples for B2B customers (Lager, 2000). During the product development phase, complementary experimental and simulation activities are often carried out iteratively.

In Fig. 2, a number of different process-industrial experimental test environments are presented, each one mimicking to varying degrees a forthcoming production process design for a new or improved product. Depending on the newness and complexity of the product concept, a single test environment can be deployed as the product’s sole development instrument, but usually a combination of complementary test environments is chosen along the experimental pathways.

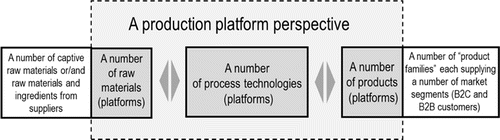

Aspects on “Product design” during the “product development” phase of the product innovation work process

Today, companies generally need to develop a number of product varieties “tailored” to different customer segments. In assembly-based industries, product innovation has undergone a dramatic change in the use of platform-based design philosophies in product development (Robertson and Ulrich, 1998), in which design elements are decoupled to achieve a separation of common platform elements from differentiating non-platform elements (Halman et al., 2003). A “modular design” with related interfaces is a well-proven industrial practice today (Suh, 2001), but in the process industries the use of this concept is still in its their infancy stage. In Fig. 3, a conceptual model for platform-based product design is depicted (Lager, 2017b). With the use of a number of overall production platforms, each containing a raw material platform, a process technology platform, and a product platform, a number of product families for a number of market segments from a number of raw materials are produced. The importance of securing high product variety in the process industries has been confirmed by Samuelsson and Lager (2019), and it could therefore be of interest to consider the possibility to incorporate a platform-based product design perspective in an enhanced work process for the innovation of non-assembled products.

Fig. 3. Platform-based design of non-assembled products: A conceptual model (Lager, 2017b).

In assembly-based industries, the dominant design construct (Utterback, 1994) is sometimes used to indicate that a product design has reached a de facto “high standard” status among customers. However, since non-assembled products in the process industries are often relatively homogenous, the construct of dominant design is not suitable. It is therefore suggested that the alternative construct of dominant performance could be deployed for non-assembled products when product properties outshine competing product specifications on the market. Such a construct could then be used as a target-setting instrument in a product innovation work process.

Packaging innovation is critical in a number of sectors of the process industries, particularly in the pharmaceutical and food & beverage industries, as it influences product safety, characteristics, changeability performance, and sales (Agariya et al., 2012). Nevertheless, since decision-making on new or improved packaging design is highly influenced by considerations of production investment (Trott and Simms, 2017), it is often not acknowledged as a part of the “core product” design. For companies in some sectors of the process industries, an integration of the “core product” and packaging (Simms et al., 2021; Simms and Trott, 2014) could be an interesting activity of an enhanced product innovation work process design, since the packaging attributes are of vital importance in product marketing and sales (Silayoi and Speece, 2007).

Aspects on “process design” during the “product development” phase of the product innovation work process

The product innovation process should always start and end with the customer, and it is thus of vital importance to understand individual customer requirements on new or improved products - the “Voice of the Customer” (Akao, 1990). Since companies in the process industries often are positioned in the middle of long value chains (Tottie and Lager, 1995) supplying business-to-business (B2B) customers, the products are in reality often ingredients or raw materials for use in a customer’s production process. Consequently, the “Voice of the Customer” is principally related to an understanding of the customers’ production processes requirements on supplied products (Akao, 2003; Lager, 2019) and of customers’ process technology development trajectories. In the perspective of the process-industrial “transformation-based” production system and the intrinsic nature of the development of non-assembled products, the overall innovation challenge is then to understand under which operational production process conditions such desired product specifications can be met. This leads to the design of a production process that is capable of producing a new or improved product at targeted product specifications, thus meeting the “Voice of the Customer”.

When an existing set-up of a production plant is reconfigured or a new plant is built for manufacturing new or improved products, there is “a window of opportunity” for equipment supplier integration and collaboration (Lager and Frishammar, 2010; Lager and Hassan-Beck, 2020), particularly during the product development phase (Trott and Cordey-Hayes, 1996). Open production (Lager et al., 2015) in this context is thus about “integrating a customer or supplier into the process company’s production process in joint selection of process equipment, mobilization of joint resources for a smooth start-up, and subsequent efficient operation” — in this context, a means to speed up the product innovation work process. Ease of manufacturing of new or improved products is nothing new in assembly-based industries, and “design for manufacturability” has long been acknowledged (Boothroyd et al., 1994). A similar need in the process industries for a cost-efficient production process is generally also recognised, but the necessity of an early integration of the development of new products with the development of related production process technology is sometimes not perceived (Lager, 2017b). Attention to OPEX (operational expenditures) and CAPEX (capital expenditures) and the processability of new products in the early phases of the product innovation work process could help to avoid problems in subsequent process plant operation.

An early consideration of process constraints can lead to product designs requiring less adaptation of existing equipment, thus reducing necessary investments (Aylen, 2013). Sometimes, inflexible process design of production plants in the process industries (Samuelsson et al., 2016; Skinner, 1978) will impact companies’ ability to accommodate the introduction of new or improved products (Skinner, 1992). In reference to earlier studies by Frishammar et al. (2012a) and Kurkkio et al. (2011), the process window of an existing production plant set-up, or new boundary conditions for a new production plant, will influence the available producibility options. An understanding of whether a new or improved product can be manufactured in a company’s existing production systems, or whether there is a need of a major upgrade or new production line or an altogether new production plant, is thus important during the product development phase of the product innovation work process (Leonard-Barton, 1992). Therefore, a proactive analysis could give further insights into development opportunities or influence choices on process design requirements for efficient production and increased production flexibility (Upton, 1994, 1997). Moreover, considering the V-shaped flow pattern (Chakravorty, 2000) of production, selective process conditions can give opportunities for the production of multiple new products and product varieties (Samuelsson and Lager, 2019).

Research Design

The research approach and a mixed-methodology perspective

This study, as one part of the total research initiative, originated from the two of the authors’ belief that there was something wrong in the industrial use of an “off-the-shelf” standard product innovation work processes in general, and especially in the use of such work processes in a process-industrial context in the development of non-assembled products. Rynes et al. (2001, p. 346) early inquired about bridging the industry–academy interface, and in a discussion of separation of research from practice MacCarty et al. (2013) thus state:

One way of addressing this is to develop research approaches that are not driven by gaps in the literature, but by the need for knowledge in practice as well in theory, through the process of problematizing and to address relevant contemporary questions and questions for the future.

Likewise, it could be advocated to take advantage of case–company representatives as practitioners in their role and capacity as “informants” during the discovery part of the research process. This is recommended by Binder and Edwards (2010) in operation management research and supported and expressed by Suddaby (2006) as follows: Letting the practitioners speak.

In this discovery-oriented project, an abductive research approach was selected (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2009) and Brodie and Peters (2020) argue that conceptual development lies in the heart of abduction. As a foundation for inquiry, abductive research may start from a discovery that the real-life empirical world does not fit theory (surprise surprise), but may also begin with testing a different, albeit existing theory, or in the application of a new conceptual framework, and accordingly Kovacs and Spens (2005):

Abduction also works through interpreting or re-contextualization individual phenomena within a contextual framework, and aims to understand something in a new way, from a new conceptual framework.

One important characteristic of abduction is the process of going ‘to and fro’ between theory and empirical evidence; a process often described as a “theory matching” or “systematic combining”, and in this approach, data collection and analysis often overlap (Dubois and Gadde, 2002). The use of multimethodology (mixed methodology) has been practiced intuitively in management research since long, but often lacks references to the methodological literature (Bazeley, 2019). Mingers and Brocklesby (1997) argue that in order to make the most effective contribution in dealing with the “real world richness”, it is desirable to go beyond using a single methodology since different methodologies often are complementary in their assumptions of the problem situation. In a similar vein, Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) define mixed methods research as follows: “The class of research where the researcher mixes or combines quantitative and qualitative research techniques, methods, approaches, concepts or language into a single study”. It is advocated by Yin (2006) that the more a single study integrates mixed methods across the total research process, the more mixed methods research is taking place. As an example of “within-stage mixed-model design”, Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) give the use of a questionnaire that includes a summated rating scale (quantitative data collection) and one or more open-ended questions (qualitative data collection). Integrating of different qualitative and quantitative approaches in a project is according to Bazeley (2019, p. 27) a core property of mixed methods research. The research design in this study and in this total research initiative could thus be characterised as a multimethodology or mixed methods research.

The research process

Interacting with case-company experts, as “judges” of a new model and concepts

The informants in this study were not asked to detail their company’s best practices but to assess a number of new conceptual propositions. The goal was thus not to investigate case–company work processes as such but to conduct a cross-case analysis of the quantitative and rich qualitative information from the informants. The case–company experts (often named respondents in surveys) answering the questionnaire, can in this study be characterised as “informants”, satisfying an early definition by Yin (1994).

The group of case–company representatives in this study can thus be viewed as “multiple informants” since their answers not only relate to their intimate knowledge of their own product innovation work processes but are also grounded in their experiences of similar sectoral operational experiences outside their own company premises (Wagner et al., 2010). The importance of theory formulation as a point of departure in case studies is emphasised by Yin as a fundamental concern in avoidance of case-studies as some sort of a “narrative of a happening”. Siggelkow (2007) underlines this point of view and argues that case studies not only give an opportunity for “getting closer to the constructs”, but also that the theory should stand on its own feet. This is ascertained to the extreme in this study, since a precursory theoretical framework was developed and published as a separate article (Lager and Simms, 2020), before the empirical part of the case study began. Multiple-case studies can be equated with multiple experiments and “replication logic” in natural sciences. However, while laboratory experiments tries to isolate the phenomenon from its environment, case studies emphasise the contextual context (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007, p. 25).

Providing case–company learning opportunities during the research process and feed-back of the research results in an action research approach

The concept, termed “innovation action research,” was suggested by Kaplan (1998) including the phases: Observe, and document innovative practice; teach, speak, write articles, and implement the concept in new organisations. In a comparison of benefits of action research and case-study research, Ollila and Yström (2010) conclude that in action research: Research and practice are integrated across time and space and for trying out a theory with practitioners in real situations and gaining feedback from this experience. This study is integrating an “innovation action research” approach, in its ambition to deliver a learning experience for the case companies and the informants, including the following activities:

Construction of a questionnaire that included many definitions, explanatory presentations and information related to each topical area.

Distribution of the final research results as articles to the case companies after project completion.

An opportunity for each company to get further assistance from the researchers as independent consultants.

Case–company selection criteria and characteristics

The population of interest for this study is the process industries worldwide, and the selected study population comprised selected companies from the “family” of process industries. A non-probability (purposeful) sampling strategy was used (Patton, 1990), and only companies belonging to the “family” of process industries were selected. In this respect, the sampling could thus be categorised as homogenous sampling, whereas it could also be categorised as heterogenous sampling in searching for diverse conditions among different sectors within the total sample (Henry, 1990). In sum, the selection process could be described as “stratified purposeful strategy” (Patton, 1990). The overall ambition was to search for shared patterns that cut across all companies within the process industries, but also to identify possible sectoral specificities. The final individual criteria for case–company selection were world-leading companies located in different countries and possessing process-industrial characteristics.

Thirty companies were invited via email; of these, 20 agreed to participate, and 19 ultimately responded. The companies belonged to the following sectors: Packaging Industries (one), Mineral Industries (one), Food & Drink Industries (two), Steel Industries (five), Forest Industries (five), and Chemical Industries (five). In the selection of case–companies, the Forest, Steel, and Chemical Industry sectors were targeted to create three sub-groups to identify possible within- and between-sectoral (dis)similarities. The case–companies have registered offices in Japan (two), Chile (one), Brazil (four), Sweden (four), USA (one), Finland (two), Switzerland (two), Denmark (one), and Germany (two). To ensure anonymity, company names and country affiliations are not disclosed. The companies are world-leading global corporations within their industry sectors, and many are major players in the marketplace. Some companies are in the supply/value chain, both downstream and upstream operators, and some cover the total chain from in-situ raw materials to end users.

The “informants” and the research instrument

In this study, the participating experts in the case–companies are called informants, adhering to an early definition by Yin (1994, p. 84). Wagner et al. (2010) further elaborated the concept as follows:

Key informants report their perceptions of these constructs, rather than personal attitudes or behaviors. In this respect, informants need to be distinguished from respondents who give information about themselves as individuals.

The company representatives in this study can thus be perceived as “multiple informants” since their answers often are grounded in an intimate knowledge of external sectoral conditions (Samuelsson and Lager, 2019; Wagner et al., 2010). Palinkas et al. (2015) recommend selecting individuals that are especially knowledgeable about the phenomenon of interest and have the ability to communicate experiences and opinions. The principal informants in the case companies held the following company positions: Senior Manager Strategy or Manager of Global Intelligence (two), Global Director of Commercialization or Head of BPM (two), Chief Technology Officer or Director of Technology (two), Director of Innovation or Innovation Manager (five), Senior Project Manager or Senior Engineer (three), and Vice President of R&D or Vice President of Innovation (three). Research results in the area of innovation and production management are sometimes presented in publications and to company practitioners in a wise that it is hard to figure out if the findings are prescriptive (normative) for what a company should aim at, or if they are only descriptive and just a snapshot of a company’s “state-of-affairs” (Cobbenhagen et al., 1990). Even if some parts of the questionnaire in this study contain questions of a descriptive nature, the study is exploratory in intent and the majority of all questions are of a normative, problem-solving kind, inquiring about the informants’ advice on how to further improve the performance of a product innovation work process. The informants were thus asked to answer both close-ended and complementary open-ended questions in two questionnaires, as “judges of the concept” (Barrett and Oborn, 2018). In the statistical analysis of the ordinal scale data from the inquiries, no kind of statistical generalisation was attempted, but to combine this information with the qualitative comments from the informants in an analytical generalisation, various statistical generalisations (Yin, 1994).

The contact person in each case–company usually also took the role of informant, and the use of questionnaires was considered suitable for a study of geographically dispersed companies. The draft first questionnaire was pilot tested by an industry professional and an academic scholar to improve the clarity of the questions. The final questionnaire was sent out electronically, enabling the informants to answer online. In most cases, one or two informants were chosen, while in some cases, the questionnaire was answered in a group session. After case–companies agreed to participate, the questionnaire and instructions were sent to the contact person. After paper revisions, the individual articles will be submitted for publication, and the published article will also be sent to the informants.

Empirical Findings

Due to space limitations, and since all original questions are presented in this section, the questionnaire is not appended. Each comment ending with sector specification is from a separate case–company.

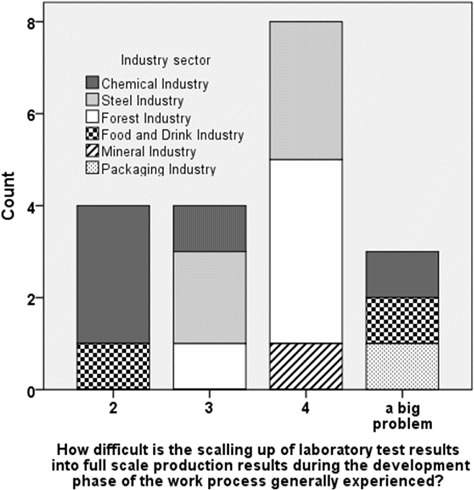

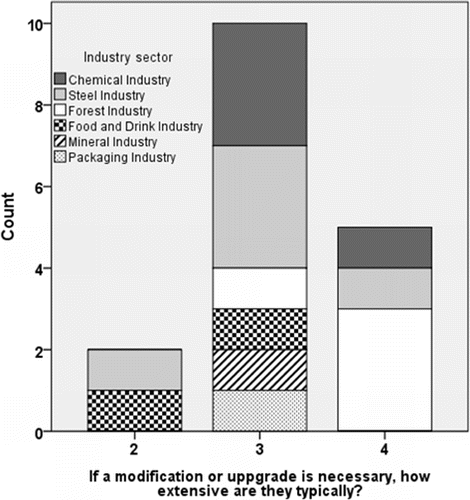

The utilization of alternative process-industrial experimental environments during the “product development” phase

In the first part of the questionnaire, the informants were initially asked (Q.1): In general, how difficult is the scaling up of laboratory test results into full-scale production results during the development phase of the work process? (1 = Not difficult; 5 = Very difficult)? The mean value of answers was 3.5 (S. D. 1.0; Skew −0.3). The sectoral distributions are illustrated in Fig. 4. Sample comments included: “Depending on project complexity, the scaling up may be very challenging” (Food and Drinks) and “Normally not a problem” (Food and Drinks).

Fig. 4. (Q.1) Experienced difficulties in scaling-up of test results (unselected categories are not displayed).

The informants were further asked (Q.2): In your company’s product innovation work process, how early does product and process modelling and simulation commence? Eleven informants responded: “In the Pre-development phase”, three “In the Development phase”, and two “In the Post-development phase”. As shown in Table 1, respondents were next asked about the use of alternative test environments and operational facilities during the product development phase of the work process (Q.3–Q.5).

In a follow-up question on pilot planting, the informants were asked (Q.6): If pilot planting is a necessary development activity, at what time is it generally carried out? Five informants responded, “In the Pre-development phase”, 12 “In the Development phase”, and one “In the Post-development phase”. Comments from informants were:

Pilot plant testing should be conducted during the development phase. However, there are cases where pilot plant tests are conducted after the fact for problems that become apparent after commercial production (Chemical).

When we are scaling up and reviewing the opportunities to take the concept to full scale trials (Forest).

Sometimes we use the pilots to do more experimental work and then the trials happen in the explore phase but normal procedure is in the development phase(Food & Drinks).

| Questions | Answers | Comments from informants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Some-times | Always | ||

| (Q.3) How often does product innovation test work solely rely on full-scale production plant trials as the final step in the product development phase? | 1 | 8 | 10 | Problems become apparent after the start of commercial production (Chemical): Needed due to regulatory requirements; validation batches (Chemical): Full-scale tests are necessary to understand the “true” material behavior in production (Steel): Most of the time this is the case (Steel): The only way to know if it works and within specifications (Steel); Industrialisation is key in the product development phase as a confirmation of the product business viability (Food & Drink); Rarely, due to equipment availability (Packaging). |

| (Q.4) How often is pilot planting a necessary development stage in your product innovation work process? | 0 | 7 | 11 | In <20% of the projects/programs (Chemical): As we are aiming at high-volume, high-speed production, we need to be very thorough in our innovation process and go through each step to gather information and knowledge (Forest); This is our normal way of working (Food & Drinks): Rarely, as the cost is too great, it is the last resort that we do as little as possible (Packaging). |

| (Q.5) How often has it been necessary in your company to build a demonstration plant for product innovation during the last 10 years? | 6 | 11 | 1 | A demo-plant was created for one project (Chemical): We have built two pilot plants (Forest): In order to limit investment risks, the demonstration plant is a must (Food & Drink): From time to time, we have rented equipment or used our suppliers’ facilities (Food & Drink): We cannot afford this on our R&D budget (Packaging). |

A preliminary synthesis

Scaling-up of the results from laboratory test-work is experienced by the informants quite differently but usually as a troublesome activity. The contradictory comments from informants in the Food & Drinks industries and the results in Fig. 4 do not indicate any sectoral patterns. However, since the issue of scaling-up is often related to product concept newness, the different importance ratings may also image the product novelty of the case–company product innovation portfolios. The results further indicate that simulation starts early, usually during the pre-product development phase.

Full-scale trials in production plants are mandatory for 10 of the case–companies and represent an important part of the validation of the results from previous laboratory test work and product and process concept development. Further use of pilot-planting follows a rather similar pattern of deployment, but even if some companies start such test work during pre-product development (see Figs. 1 and 2), the general impression is that this step belongs within the product development phase.

The comments further suggest that the use of pilot-planting could be a useful instrument in all phases of the total work process, even during the post-launch phase. This finding is rarely mentioned in the extant literature but indicates that some product problems first become visible during true commercial customer testing. Pilot planting after product launch can thus be important in solving problems that are difficult to foresee during early test work. However, while the comments indicate that further test work in demonstration plants can be necessary, the findings indicate that such activities are rare during product development of non-assembled products.

Development and design of new or improved products

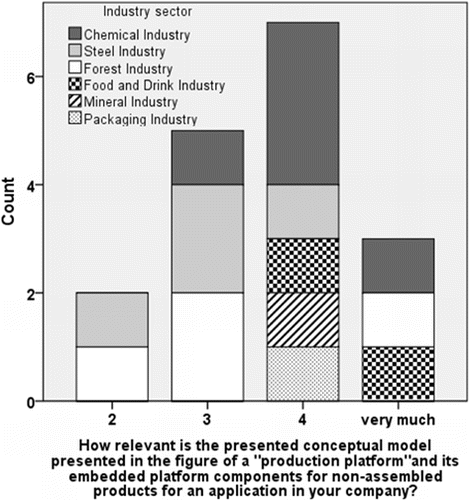

In the second part of the questionnaire, the informants were asked about product design aspects that should be considered during the product development phase — specifically, “product variety” development and related “platform-based” design of non-assembled products. The conceptual model (see Fig. 3) was included and explained in the questionnaire.

Informants’ rating figures and comments on the individual questions (Q.7–Q.9) are further presented in Table 2, and in Fig. 5, sectoral divergencies related to question Q.9 are introduced.

Fig. 5. The relevance of the conceptual model of “platform-based” design for use by the case-companies (unselected categories are not displayed).

| Questions | Answers | Comments from informants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. dev. | Skew | ||

| (Q.7) How important is securing opportunities for “product variety development” during the development phase of the product innovation work process? (1 = Not important; 5 = Very important) | 4.0 | 1.0 | −0.4 | Variety is especially important for specialty chemicals (Chemical); We have been developing our products aiming to fit the specific requirements of our customers. As a result, we have tailored specifications to customers’ processes. We understand that this concept is very important to the innovation process (Steel); In our industry, customers do not always seek personalized products. Instead, process efficiency, reliability, and consistency are key parameters for them (Forest); We start with a particular technology. Then when we know it works, application development occurs for different customers (Packaging). |

| (Q.8) Have you previously discussed the concept of “platform-based product design” in your company? (1 = Never; 5 = Very often) | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | Product variety development is an historic reality to our company (Steel); This is one way of diversifying and fulfilling different end-use segments and customer demands (Forest); The scope may be extended to a range instead of a single product (Food & Drink); It’s getting more and more important to have “late” differentiation in the process to be able to be efficient and cost effective (Food & Drink). |

| (Q.9) How relevant to your company is the conceptual model presented in the “Production platform” figure and its embedded platform components for non-assembled products? (1 = Not at all relevant; 5 = Very relevant) | 3.7 | 0.9 | 0.2 | The conceptual model looks very powerful and comprehensive (Food & Drink); We are starting to discuss more in this way, butwe are not there yet fully (Food & Drink); The use of a production platform is central, as discussed above, but we often use new materials developed by our suppliers and develop bespoke products for customers (Packaging). |

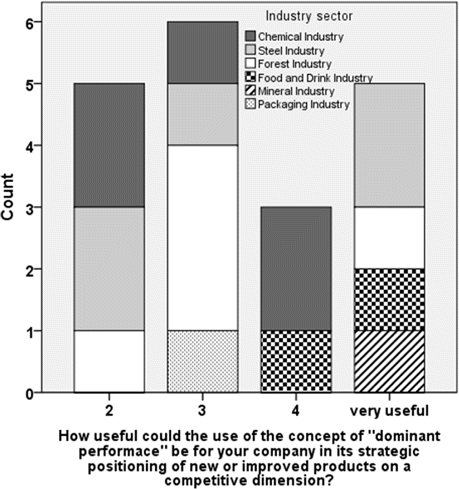

In a follow-up question to Q.9, informants were asked (Q.10): Would it be of value for your company to learn more about “platform-based” philosophy? Eleven informants responded yes and four no. The questionnaire then asked about “dominant performance” and “packaging development” of non-assembled products (Q.11–Q.12; see Table 3). The results related to case-company usability of the construct of “dominant performance” (see Table 3) and the sectoral divergencies are further presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. The usefulness of the concept of “dominant performance” (Q.11) in the strategic positioning of new or improved products in a competitive dimension (unselected categories are not displayed).

| Questions | Answers | Comments from informants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. dev. | Skew | ||

| (Q.11) How useful could the concept of “dominant performance” be for your company in its strategic positioning of new or improved products on a competitive dimension? (1 = Not useful; 5 = Very useful) | 3.4 | 1.2 | 0.2 | Although we don’t have a formal “dominant performance” analysis tool, the concept is relevant when we evaluate our product performance compared with the competitors (Steel);Historically very much a part of our innovation strategy (Steel); The dominant performance can be defined by technology purity, cost-benefit, low-cost, etc. Hence, it does not provide much extra compared to how we do it today (Forest);Do not quite see the benefit of this (Forest); It would begood to learn more on that concept (Forest); We are using the concept of 60/40 where new products must be min 60% superior then competition (Food & Drink); Don’t know that much about it butsounds interesting (Food & Drink). |

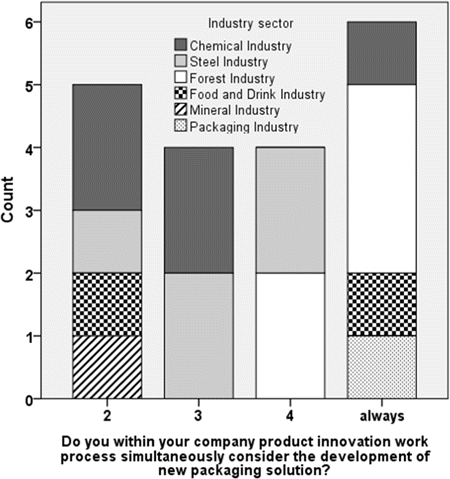

| (Q.12) Do you, within your company’s product innovation work process, simultaneously consider the development of new packaging solutions? (1 = Never; 5 = Always) | 3.6 | 1.2 | −0.1 | The food business requires improved packaging (Chemical); We have a special innovation platform aiming for lightweight packaging solutions (Chemical); To some extent, it is through our customers who own the packaging side (Steel); Very important to do an early development – impacts safety, product protection, and logistics (Forest); Need to talk about “packaged product” and not product. A product is almost never sold without packaging (Food & Drink); We always look at current packaging options first, and very seldom do we invest in new packaging solutions; it’s too expensive (Food & Drink) |

In a follow-up to Q.11, informants were asked (Q.13): Could this construct be of value to introduce and deploy in an improved product innovation work process? Eight informants responded yes and six no.

In Table 3, the results related to packaging development (Q.12) are presented, and sectoral divergencies are further presented in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. (Q.12) Case–companies’ simultaneous development of packaging solutions (unselected categories are not displayed).

As a complementary question, the informants were further asked (Q.14): Is an integrated design of the core product and packaging during the Development phase recommended in your company innovation work process? Eight answered yes and nine no. Comments from informants were as follows:

We understand the importance of packaging. However, there are no examples where product development and packaging solutions are linked (Chemical).

Sometimes, but not for the bulk (Forest).

An integrated design of product, packaging and process is crucial (Food & Drink); It’s a part of our process but most often we don’t change packaging (Food & Drink).

Packaging is our core product. We do try to integrate with customers and their product development, but often we are involved too late, and it is not possible (Packaging).

In a follow-up to question (Q.14) the informants were asked (Q.15): Could it be of value to introduce and deploy in an improved product innovation work process? Six informants said yes and eight no.

In the final part of this section of the questionnaire, the informants were asked (Q.16): Does your work process prescribe test-marketing of new or improved products during the Development phase of the product innovation work process? Twelve of the informants responded yes and five no. A follow-up question asked (Q.17): Could it be of value to introduce and deploy in an improved product innovation work process? Eight of the informants responded yes and four no. Comments from informants:

Test sales of prototypes are important (Chemicals).

Usually this also involves customer testing of a new product candidate (Steel).

We always try to involve our lead customers for that product concept in the development process (Forest); We prescribe interaction with lead customers to get input about the concept (Forest).

Marketing tests are part of the development phase and performed in an agile approach (Food & Drink); We are discussing this a lot, but the retailers are not there. We do it from time to time and test launch (Food & Drink).

Our sales team might take out some samples, but we do not really undertake a formal test marketing (Packaging).

A preliminary synthesis

The high importance rating of “product variety development” stands out. Even if the “platform-based” product design concept is rather new to the informants (see Q.8), the rating figures for Q.9 and related comments like “the use of a production platform is central” demonstrate that this concept has high relevance and could be a topical area for further development. Comments that “the conceptual model looks very powerful” and “we are starting to discuss more in this way” (Food & Drinks) underscore that, when developing a new product in the process industries, it could be of interest to create a product platform able to produce a multitude of future product varieties. This impression is further underscored by the fact that 11 of 15 informants were interested to learn more about this development philosophy.

The construct of “dominant performance” was introduced to the informants in the questionnaire together with a brief presentation of the more established construct of “dominant design”. Even with a mean-value rating figure of 3.4, the sectoral distribution of the answers in Fig. 6, underscored by the mixed recommendations for use in an enhanced work process, indicates a rather disparate estimated usefulness of the construct. The high importance ratings by the Food & Drinks industry underscore that those two case–companies are in the business of developing fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG). Nevertheless, comments like “the concept is relevant”, “historically very much a part of our innovation strategy”, “good to learn more on that concept”, and “sounds interesting” indicate that this construct could be of interest to further develop into a positioning tool in an enhanced product development work process.

In view of the results related to a need for packaging development and integrated packaging design alongside core product development, the contrary positions (see Fig. 7) of informants in the Food & Drinks Industry stand out. In the Forest industries, the high ratings likely reflect the fact that “packaging solutions” are directly linked to either their core businesses or their own product offerings. Many informants did not recommend including packaging development in an enhanced product innovation work process. The comment from the Packaging industries that “we are often involved too late” indicates that even if companies utilise available packaging alternatives, an early decision in the work process regarding necessary packaging development could be advantageous.

The findings on whether test marketing is included in the product development work process (12 of 17 responded yes) and comments from informants (e.g., “test sales of prototypes”, “usually involves customer testing of a new product candidate”, “we always try to involve our lead customers”, “we prescribe interaction with lead customers”, “marketing tests are performed in an agile approach”) demonstrate that test marketing should be included as an option for new products in the development of an enhanced work process.

Development and design of a production process for new or improved products

Process design and the integration of equipment manufacturers

In the final part of the inquiry, the informants were asked (Q.18): In your product innovation work process, how strongly are the processability (manufacturability) aspects considered during the product design phases (1=Not at all; 5=Very strongly)? The answer was Mean value=4.5 (S.D. 0.7; Skew −1.1). Comments from informants were as follows:

This issue is strongly recognised for products that are difficult to scale up (Chemical).

Very strongly! As we have large equipment with clear technical limitations (for example, related to product dimensions), manufacturability is a go/no go in our innovation process (Steel).

Processability is one of the dimensions for design prioritisation during the innovation work process (Food & Drinks); We always have a high focus on the cost-of goods-sold (COGS) (Food & Drinks).

This is central, much of our work is on ensuring processability (Packaging).

The informants were next asked (Q.19): When are process configuration/preliminary process design recommended to begin in your product innovation work process? Seven informants responded “In the Pre-development phase”, 10 “In the Development phase”, and none “In the Post-development phase”. Comments from informants:

Feasibility studies are implemented during the pre-development phase (Chemical).

The earlier the better (Forest).

As early as possible, and at the development phase, the product concept is becoming clear enough to review the production process implications (Forest).

Process design need to start at earliest stage of the innovation work process (Food & Drinks).

As discussed above, this is a central aspect. Ensuring production viability (Packaging).

The informants were further asked (Q.20): When are equipment/technology suppliers recommended to be involved in your product innovation work process? 12 informants answered during the pre-development phase, and the remaining six during the Development phase. One informant from the Forest industries said they should be “involved throughout the work process”. Comments from two informants from the Food & Drinks industries were “Suppliers need to be involved at the earliest stage of the innovation work process” and “I would say that we are too late with this type of feasibility in general and this is an area for improvement”.

The informants were then asked (Q.21): Does your work process prescribe the development of a “digital twin” of your intended production system? Three answered yes while 15 answered no. However, in inquiring if this could be of value to deploy in an improved product innovation work process, 11 answered yes and three no. Comments from informants:

Definition of digital twin is very important. If DCS control system is included in “D-T”, most of process prescribe the development of a “D-T” (Chemical); Could be of value in general, but not very much for our company (Chemical).

We haven’t used the digital twin as a regular tool in our innovation process; (Steel) We’re working on it, but exactly how, when and what I don’t know (Steel); Today we usually cannot make a good enough twin to reap the benefits (Steel).

Digital twins are already used in some cases, but not prescribed and demanded yet (Forest); We work with digital twins (Forest); We have started to look at “digital twins” (Forest).

In case of complex projects, building a digital twin may add a lot of value (Food & Drinks).

This is not done (Packaging).

Utilisation of existing company production plants and set-ups

The informants were next asked (Q.22): If modifications or upgrades of the production system are necessary, how extensive are they typically (1=Very minor; 5=Very extensive)? The mean value of answers was 3.2 (S.D. 0.6; Skew −0.1). The sectoral distributions are illustrated in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. (Q.22) Necessary production system upgrades (unselected categories are not displayed).

Informants were next asked about necessary renewal of the production process for the production of new or improved products (see Table 4).

| Questions | Answers | Comments from informants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Some-times | Always | ||

| (Q.23) How often is it necessary to modify or upgrade a production line in an existing plant in order to be able to manufacture a new or improved product? | 1 | 18 | 0 | Small adaptations to existing lines are needed due to the specific product requirements (Chemical); Rarely(Steel); This is quite common (Steel); Most of the time (Forest); Most of the times, modifications are needed (Forest); It depends on the project; novelty, complexity, new technology (Food & Drinks); Does not happen often but it can be dosing systems, new tanks, etc. (Food & Drinks); Quite often, but we try to minimize this. This is often a key focus of early development, to see how small the change can be to ensure viability (Packaging). |

| (Q.24) How often is it necessary to build a new production line in an existing production plant in order to be able to manufacture a new or improved product? | 2 | 15 | 0 | Very seldom (Chemical); Very rarely (Steel); It’s not that common (Steel); If we consider innovative product/processes, so far we haven’t done it (Forest); Very seldom due to the size of the investment (Forest); It depends on project novelty, complexity, new technology (Food & Drinks); Rarely; we spend a lot of the early stages of the project trying to get the concept to work on the production line (Packaging). |

| (Q.25) How often is it necessary to build a new production plant in order to be able to manufacture a new or improved product? | 7 | 11 | 0 | Never done it so far anyway (Steel); This is very rare and often linked to capacity expansion (Steel); If we consider innovative product/processes, so far, we haven’t done it (Forest); It would be a huge investment. It has not been on the table for a long time. (Forest); Happens very seldom, every 5th year (Food & Drinks). |

A preliminary synthesis

The empirical findings clearly demonstrate, regardless of sector, the high importance of the area of processability (manufacturability) of new or improved products during the “product development” and design phase of the product innovation work process, with a very high mean value of 4.5 for Q.18. Comments from informants support this impression: “this issue is strongly recognised”, “manufacturability is a go/no go in our innovation process”, and “this is central; much of our work is on ensuring processability”. This underscores the fact that designing the product sets technical boundaries for the new product and its production process and also indicates future OPEX levels and CAPEX needs. Further result from Q.19 indicates that preliminary process design usually takes place during the “Product development” phase, but many case–companies see a benefit in performing it as early as possible, during the “Pre-product development” phase (see Fig. 1).

The findings indicate that equipment and technology suppliers are important actors in the process-industrial eco-system, and the majority of the informants recommend that they should be involved during the “Pre-product development” phase of the work process. One informant recommended involvement “throughout the work process”, and another stated that such involvement generally starts too late and should be improved. There is a consensus across all sectors of the case–companies that equipment suppliers should be involved early in the product innovation work process. The results from the question regarding implementing a “digital twin” as part of the innovation process indicate that this approach is still in its infancy for the case–companies. The comments indicate that several companies that are familiar with this concept strongly recommend its inclusion in an enhanced work process.

The empirical findings with regard to necessary modifications and upgrade of case–companies’ production systems (Q.22) (see Fig. 8) show rather modest production system upgrades as a consequence of the development and introduction of new or improved products (possibly more extensive in the Chemical industries). The empirical findings presented in Table 4 indicate that upgrading existing production lines is the most common situation (“this is quite common”, “most of the time”, “quite often, but we try to minimize this”). Conversely, the findings show that the need to build a new production line is uncommon (“very seldom”, “very rarely”, and “we spend a lot of the early stages of the project trying to get this concept to work on the production line”), most likely due to heavy CAPEX intensity in the process industries.

Discussion

Introducing a novel “transformation-based” perspective on product innovation in the “family” of process industries

In reference to the title of this paper, the intrinsic nature of product development in the “family” of process industries was initially presented in the introduction in the perspective of process-industrial manufacturing contextual characteristics and product innovation inherent conditions. It was concluded that the two industrial cluster categories, the “process industries” and “other manufacturing industries”, could be better characterised as “transformation-based” and “assembly-based” industries. Consequently, it was further deduced that “in assembly-based” production systems, the product to a great extent defines the production process, whereas in a “transformation-based” production system, the production process to a great extent defines the product. This novel perspective on product innovation of non-assembled products in the process industries gives first of all a firmer theoretical underpinning and guidance in the further development of the previously developed “structural process model” of the product innovation work process introduced in Fig. 1 (Lager and Simms, 2023). Moreover, it further clarifies that all alternative process-industrial experimental environments, as instruments for product development, more or less try to mimic an envisaged production process for a new or improved product. Consequently, different experimental environments are not only prime product innovation tools for the development and design of non-assembled products, but they are also process innovation tools for the development and design of interdependent production process technology.

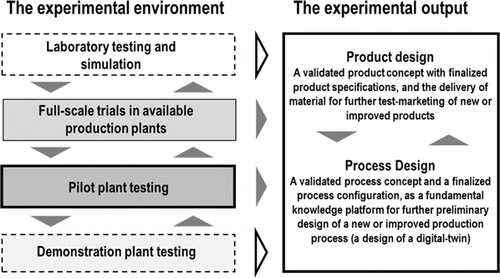

The experimental environment for the development of non-assembled products and expected outcomes

The empirical findings demonstrate that during the “product development” phase of the work process, full-scale production trials in production plants and pilot-planting are the select dominant experimental environments. The use of pilot-planting generally commences during the product development phase and not during conceptualisation as reported by Frishammar et al. (2014b). However, the findings further indicate that both full-scale production trials and pilot-planting are important instruments for solving customer production problems after product launch. This new finding not only underscores the importance of the post-launch follow-up phase of the work process (see Fig. 1) but also pinpoints the importance of company access to pilot-planting experimental facilities to avoid production disturbances in full-scale production trials. Complementing the previously presented conceptual model in Fig. 2, alternative experimental routes in the development of non-assembled products and related expected outcomes are presented in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. A conceptual model of alternative experimental environments for the development of a new or improved production process for the production of a new or improved product and the expected output from the test work.

In view of the upcoming sustainability challenges facing many sectors of the process industries, the development of new product and process concepts will likely necessitate not only the use of existing experimental facilities but also the use of new kinds of pilot plants and demonstration plants. Managing the selection of the alternative experimental routes depicted in Fig. 9 in consideration of shorter development cycles, low-cost development, minimal production plant disturbances during full-scale trials, and customer risk avoidance in the use of new products will consequently be important for future innovation management of excellence.

The output from experimental test work and simulation is primarily a validated product and process concepts, as shown on the right side of the conceptual model. Further activities in product design are the delivery of test batches as beta (demo) samples for customer trials and test marketing. The finalised process configuration is the foundation for a preliminary process design and, in some instances, the design of a “digital twin”. The conceptual model presented in Fig. 9 illustrates this fact and further shows that the experimental output both consists of a new “product design” and lays the foundation for the development of a new related production “process design”.

Empirical findings related to the area of product design

The high importance ratings for securing the possibility of future product variety development indicate not only that this aspect should be recognised in work process design but also that the related construct of “platform-based” product design could be of interest for further theoretical development and empirical research as well as further deployment in an enhanced work process. Because of the scarce use of line extensions by the case–companies in their product development, it could be of interest to further investigate CAPEX and OPEX in production system design related to parallel processing alternatives.

The informants’ mixed responses related to “dominant performance” does not seem to have a sectoral pattern but may reflect the case–companies’ product portfolios related to functional and commodity products. One comment from an informant advised that “dominant performance” in a B2B context should not only be related to product specifications but also include other aspects like costs and benefits for the user, which could make the construct more universally useful for the process industries. The complementary suggestion from another informant introduces a scale for this construct in the use of a 60/40 model where new products must be at least 60% superior to the competition. This comment illustrates the importance of the development of the full “Voice of the Customer” in the QFD methodology and the inclusion of product benchmarking activities.

Despite the contradictory results from informants in the Food & Drinks industry, there seems to be a sectoral difference regarding simultaneous development of packaging solutions and the “core product” for companies supplying B2B and B2C customers. Nevertheless, the comments highlight a possible need for packaging development during the pre-product development phase of the work process. The inclusion of test marketing in the work process is recommended by the informants, and for products for B2B customers, tests with “lead users” are recommended in the work process design. Since sustainability topics are increasingly important for most companies, test marketing of new products would enable an opportunity to develop more sustainable packaging designs as part of an improved innovation process.

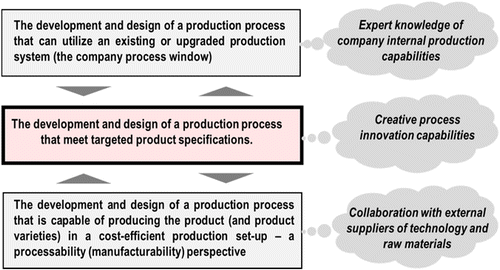

Empirical findings related to the area of process design

The empirical results confirm that in product development of non-assembled products in the process industries, product processability (manufacturability) is critical. The comment “manufacturability is a go/no go in our innovation process” accentuates this perspective and supports the theoretical model presented in Fig. 1. Consequently, preliminary process design is recommended to begin “as early as possible”, possibly even during the pre-product development phase. In a similar vein, early involvement of equipment/technology suppliers is advised. When a company starts to work with digital twins, this approach is generally easier to apply in the post-product development phase, improving product, and process performance by building a twin of the current process part the company wants to improve. With the strong emphasis in the process industries to implement further automatization and digitalisation as tools improving process efficiency and product quality, it is likely that more companies will implement digital twins as part of the future innovation process.

Case–company use of existing production facilities in the introduction of new or improved products shows that they usually try to manufacture products in existing production plant set-ups, sometimes upgrading and thus usually avoiding new line extensions. In the perspective of the previously discussed aspects on “process design” related to “product design”, and the empirical findings, three objectives to meet in the design of a production process and related proposed desirable organisational capabilities are given in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. Three objectives to meet in the development of a production process design for the manufacturing of new or improved non-assembled products and related necessary organisational capabilities.

Management Implications

In reference to Figs. 9 and 10, the conceptual models can be deployed as a guiding framework for the product-development phase in an improved product innovation work process design. The constructs of “platform-based product design” and “dominant performance” could also be of further interest to introduce and utilise. The findings also show that the often-rigid production set-ups and the heavy CAPEX for new production systems in many sectors of the process industries may create too strong a focus on incremental product innovation and even possibly a disregard for potentially interesting more radical breakthrough product innovation projects. The identification of the three interrelated objectives and related capabilities in the development and design of a novel production system for new or improved products can be integrated in the development of a proper Gate structure for an enhanced work process design.

In a previous study of the organisational design for process innovation in the process industries (Bergfors and Lager, 2011), three alternatives for organising process innovation were investigated: Within the R&D function, within the Production function, or both. It was concluded that a more radical process innovation should be associated with the R&D function. In the perspective of the findings from this study, one could ponder whether more incremental product innovation should be attached to the Marketing and Sales function whilst more radical product innovation of non-assembled products should be associated with the R&D function? For companies in the process industries serving mainly B2B customers, customer requirements are in reality mainly requirements of a customer’s production process. Understanding such demands require a deep understanding of the customer’s production technology (Lager and Storm, 2012). In consequence, since Marketing and Sales must be heavily involved in all kinds of product innovation, this is an argument for Product Management and Technical Services with a profound knowledge of the customers’ production systems.

Theoretical Contribution and Research Limitations

This study used a questionnaire with both quantitative (using five-point ordinal scales) and related qualitative (open-ended) questions, and the results from both are merged in the analysis of the findings (Meredith, 1998, p. 450). Because of the limited number of case–companies, no statistical generalisation of the results is attempted. However, it is argued that the combined results from this study are valid for companies in the “family” of process industries in an analytical generalisation (Yin, 1994). In reference to the scientific utility of a theoretical contribution (Corley and Gioia, 2011), it is argued that this study provides the following contributions.

First, in characterising the two different industrial clusters as “transformation-based industries” and “assembly-based industries” it is concluded that in the former, the production process largely defines the product, whereas in the latter, the product defines the production process. This implies that production process aspects must be considered much earlier in the product innovation work process for non-assembled products. This consideration is of vital importance to consider in the design of a product innovation work process and can serve as a mental model that can be further developed and expanded into a more comprehensive framework.

Second, this study empirically tests one part of the previously presented generic “structural process model” (Lager and Simms, 2023) in Fig. 1 and provides a more detailed process-industry-specific conceptualisation of what constitutes the product development phase of the product innovation work process for non-assembled products. It is found that the alternative experimental facilities (e.g., laboratories, pilot plants, full scale production trials, and demonstration plants) for product innovation in “transformation-based industries”, in contrast to the product design instruments in “assembly-based industries”, attempt to simulate the expected future production system for the new product.

Third, previous research has suggested that pilot-planting is part of the pre-product development phase of the work process (Frishammar et al., 2014b). In this study, this has been empirically tested in new sectors of the process industries (Chemical, Forest, Food & Drink, and Packaging). It is not only found that the “Product development” phase is the dominant phase for pilot-planting in the process industries but also that, depending on project circumstances, this instrument should be deployed throughout the whole work process. Consequently, it is suggested that pilot-planting could possibly be even more important to utilize in the “Post-launch follow-up phase”, when customer feedback on supplied product performance is available.

There are a number of research limitations related to this study, and mainly related to the research approach and methodological issues. The use of an abductive research approach is still an unconventional starting point, but in the exploration and further development of new innovation management operational practices, an area which can be characterised as applied science, this approach is not new but rests on previous recommendations for innovation action research (Ollila and Yström, 2010; Kaplan, 1998). The use of a multimethodology (mixed-method) research design, opens up for a number of questions related to the select focus on some aspects of a methodology, while paying less attention or even disregarding others. Nevertheless, in reference to Mingers and Brocklesby (1997), it is argued that different parts of this study, benefitted from different methodology perspectives in the research design. It is thus recommended that the deployment of a multimethodology research design and integrating perspectives from different methodologies should be further developed and refined into a more coherent methodological framework. The use of a well-defined questionnaire supports the reliability of the findings, and the combination of both qualitative and quantitative information from informants (experts) in the topical area reinforces the study’s construct validity. However, the common reliance on single informants from the companies is a research limitation. Nevertheless, the cross-case analysis based on the quantitative and complementary qualitative case–company information is argued to be robust.

Conclusions and Further Research

Regarding the first research question, it is recommended that the different contextual and inherent characteristics of the “transformation-based” production system in the process industries, compared with an “assembly-based” production system in other manufacturing industries, should govern the design of the overall product innovation work process for non-assembled products, its related operational tools, and methodologies for such development undertakings. Furthermore, those characteristics will also influence the final design of the production system for manufacturing new or improved non-assembled products in the process industries, and as such, the product development work process is actually a simultaneous development of the forthcoming interdependent production process.

Regarding the second research question, in the iterative development and upscaling of product and process concepts into a final product design and process design, related instruments and operational facilities are of a process innovation nature, mimicking an envisioned forthcoming production process configuration, and tentative future operational conditions. The instruments and methodologies for the development of non-assembled products are thus vastly different from those in other manufacturing industries. The empirical findings support the conceptual model presented in Figs. 1 and 2 and identify full-scale production trials in production plants and pilot-planting as the dominant experimental environments during the “product development” phase of the work process. Even if pilot-planting usually takes place during the product development phase, the findings suggest that it can be useful for solving customer production problems after product launch. In conclusion, the experimental output from the “product development phase” both consists of a new “product design” and lays the foundation for the development of a new related production “process design”, according to Fig. 9.

In reference to the third research question, three aspects of product design during the product development phase have been explored. The case–company informants generally place high importance on product variety development, indicating that this aspect should be recognised in work process design. The use of a “platform-based” product design philosophy could thus be of interest for further deployment in an enhanced work process as well. Even if there was a rather mixed responses from the informants related to the usability of the construct “dominant performance”, this accentuates the importance of the “Voice of the Customer” including product benchmarking activities. Despite the sectoral difference regarding simultaneous development of packaging solutions and the “core product”, a possible need for packaging development is suggested to be highlighted during pre-product development. The informants recommend test marketing in the work process, in the use of “lead users”.