A versatile platform for single-molecule enzymology of restriction endonuclease

Abstract

Enzymes are the major players for many biological processes. Fundamental studies of the enzymatic activity at the single-molecule level provides important information that is otherwise inaccessible at the ensemble level. Yet, these single-molecule experiments are technically difficult and generally require complicated experimental design. Here, we develop a Holliday junction (HJ)-based platform to study the activity of restriction endonucleases at the single-molecule level using single-molecule FRET (sm-FRET). We show that the intrinsic dynamics of HJ can be used as the reporter for both the enzyme-binding and the substrate-release events. Thanks to the multiple-arms structure of HJ, the fluorophore-labeled arms can be different from the surface anchoring arm and the substrate arm. Therefore, it is possible to independently change the substrate arm to study different enzymes with similar functions. Such a design is extremely useful for the systematic study of enzymes from the same family or enzymes bearing different pathologic mutations. Moreover, this method can be easily extended to study other types of DNA-binding enzymes without too much modification of the design. We anticipate it can find broad applications in single-molecule enzymology.

1. Introduction

Enzymes, generally proteins or few ribonucleic acids, are macromolecular biological catalysts which play irreplaceable roles in almost every physiological activity in vivo. Many natural and artificial enzymes are developed for the acceleration of chemical reactions in the synthesis industry.1–3 For example, some complicated drugs can be produced by one-pot enzymatic synthesis in vitro.4 Enzymes are also important tools for molecular biology, bioengineering and materials science. Restriction enzymes and DNA ligases are indispensable tools for recombinant DNA techniques. Cas9 involved in CRISPR system is now the star for genome engineering,5,6 gene knockout or knockdown,7 transcriptional activation8 and cancer research.9–11 Many enzymes are used to construct hydrogels,12–14 catalysts15,16 and drug delivery systems.17–19 In all these applications, understanding the action mechanism of enzymes is critical, which lays the foundation for the improvement of their performances. On the other hand, the change of activities of enzymes in vivo due to mutations is tightly related with many diseases.20 Fundamental enzymology studies have a strong impact on medicine and healthcare. Many techniques, such as stopped-flow system21,22 and continuous-flow system,23,24 have been used to study enzymology at the bulk level.

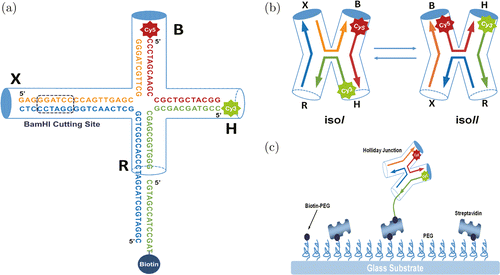

Single-molecule studies can provide many insights of enzymes that are otherwise inaccessible from bulk studies. Currently, single-molecule techniques have been proven to be powerful tools for studying folding dynamics of proteins25–27 and DNA,28–30 biomolecular interaction31–33 and enzymatic reaction dynamics.34–37 Specifically, single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (sm-FRET) is widely applied for studying the structure, dynamics and function of proteins at the single-molecule level in real-time.38–41 In typical sm-FRET studies, a pair of donor–acceptor fluorescent dyes is introduced to suitable positions of the protein or nucleic acid structure. The distance change of the two labeled positions can be monitored by the FRET effect of the two fluorophores with nanometer resolution in situ, making it a perfect tool for enzymology.41–44 However, these studies relied either on the specific labeling of enzyme and the substrate using fluorescent dyes38–44 or on the intrinsic fluorescence of the products.45 The former method needs tedious fluorophore labeling and is technically difficult to implement to different systems. The latter one is limited to only a few enzyme systems. In addition, the labeling of fluorescent dyes might affect the intrinsic dynamic of an enzyme. Moreover, in many enzymological processes, the structural changes are too small to be detected even with the state-of-the-art sm-FRET techniques. Herein, we present a versatile platform to measure the activity of DNA endonuclease, based on Holliday junction (HJ) [Fig. 1(a)]. HJ comprises four arms namely X, B, R and H, with two stable native conformations: The “isoI” state with the B-arm far from the H-arm and the “isoII” state with the B-arm close to the H-arm [Fig. 1(b)].46 The intrinsic dynamics of HJ has been extensively studied by sm-FRET and theory.46–49 We use the dynamics of HJ as the reporter for the enzymatic reactions taking place on the X-arm. We hypothesize that binding of an enzyme to the X-arm and subsequent enzymatic reactions can affect the intrinsic dynamics of HJ, thus can be detected by analyzing the dynamics of HJ. A similar method was used to study protein-DNA interaction previously by Sarkar et al.50 In this method, the fluorescent dyes are labeled on the reporter arms (H- and R-arms) of HJ instead of the enzyme or the substrate directly, which minimizes the side-effect of dye labeling on the dynamics and activity of the enzyme. Moreover, the enzyme-binding arm (X-arm) and the surface-immobilizing arm (R-arm) are decoupled with the reporter arms, providing plenty of opportunities for the studies of various DNA-binding enzymes. In principle, this method can be used to quickly measure the activity of different enzymes without the need to change the fluorescent substrates. Using restriction enzymes as the example, enzyme binding may slow down the intrinsic dynamics of HJ due to the stabilizing of the two native states. However, after the enzymatic reaction, the X-arm is cut and becomes shorter, leading to faster conversions between “isoI” and “isoII” states. Therefore, the substrate binding and catalytic activity can both be measured from the change of the dynamics of HJ. We have experimentally proved this idea using BamHI as the representative restriction endonuclease [Fig. 1(c)].

Fig. 1. (Color online) (a) The scheme of designed HJ. The b-strand (red), x-strand (orange), r-strand (blue), h-strand and biotin strand (both green) form the HJ with four arms (B, H, R and X). (b) The scheme of “isoI” and “isoII” states. The “isoI” state has longer distance between Cy3 and Cy5 than “isoII” state. (c) Surface immobilization strategy for sm-FRET experiments. The components are not drawn to relative scale.

2. Method

2.1. The preparation of HJ

HJ-b-strand (5′-Cy5-CCCTAGCAAGCCGCTGCTACGG) and HJ-h-strand (5′-Cy3-CCGTAGCAGCGCGAGCGGTGGG) were purchased from Invitrogen (ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc., USA). HJ-x-strand (5′-GAGGGATCCCCAGTTGAGCGCTTGCTAGGG), HJ-r-strand (5′-CGGATGGCTACGATCCCACCGCTCGGCTCAACTGGGGATCCCTC) and biotin strand (5′-CGTAGCCATCCGAT-Biotin) were purchased from GenScript (Nanjing, China). All the b-, h-, x-, h- and biotin-strands were dissolved in TN buffer (50mM Tris, 50mM NaCl, pH=8.0), respectively. Then, five kinds of strands were mixed in TN buffer to reach the final concentration of 1μM and the mixture was slowly annealed by PCR machine (slowly cooled from 95∘C to 15∘C, then raised to 65∘C and dropped to 25∘C for three cycles and finally cooled to 4∘C). The purity of HJ was confirmed by native-PAGE.

2.2. The digestion of HJ

The mixture of HJ and BamHI (R0136S, New England BioLabs, USA) was incubated at 37∘C for 1h and then analyzed by the denatured PAGE followed by silver staining.

2.3. Modification of the glass coverslip

The scheme of coverslip modification is shown in Fig. 1(c). Coverslip was biotinylated following previous reports.51–53 The 0.15-mm glass coverslip (24×40mm2, Micro Cover Glasses No. 1, VWR International, LLC) was cleaned in piranha solution (98% H2SO4:30% H2O2=7:3, v/v) for 30min to be hydroxylated. After thoroughly rinsing with MilliQ-water, the coverslip was dried under argon airflow. Then we gently heat the coverslip using blast alcohol burner to decompose any possible fluorescent impurities. After cooling to room temperature, the hydroxyl-functional coverslip was immersed in acetone solution containing 10% (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 30min and rinsed thoroughly with acetone and MilliQ-water, respectively. After being dried under argon airflow, the amino-functional coverslip was PEGylated by immersing in aqueous solution (pH=8.0) containing 100-mM NaHCO3, 15mg/mL Biotin-PEG-SVA (MW: 5 kDa, Laysan Bio, Inc., USA) and 150mg/mL Methyl-PEG-SVA (MW: 5kDa, Laysan Bio, Inc., USA) for at least 3h. Finally, the coverslip was rinsed thoroughly with MilliQ-water, followed by drying under argon airflow. The biotin-functional coverslip should be kept in dark and be used freshly.

2.4. Sample cell for sm-FRET experiments

The biotin-functional coverslip was made into a sandwich structure cell with several sample channels. TN buffer containing 1% Tween 20 (v/v) was added and incubated for 20min, and then was rinsed with TN buffer three times. TN buffer containing 200μg/mL streptavidin was added to each sample channel and incubated for 1min. After rinsing with TN buffer three times, TN buffer containing 10–50pM HJ was injected into the sample channel and incubated for 20min then rinsed with TN buffer three times.

2.5. Sm-FRET experiments

The single-molecule FRET experiments were executed on an Olympus IX-71 with an oil immersion UAPON 100×OTIRF objective lens (numerical aperture=1.49, Olympus). Cy3 was excited by a 532-nm laser and the emission fluorescence of Cy3 and that of Cy5 were split into two channels by a dichroic filter (FF640-FDi01, Semrock). The emission fluorescence of two channels passed through two band-pass filters (FF01-585/40 and FF01-675-67, Semrock), respectively, and the final fluorescence signals were collected by an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (IXon897, Andor Technology). The sm-FRET experiments were carried out in Tris buffer (50mM Tris, pH=8.0) containing 50mM MgCl2. About 1-μL BamHI (20 units) was diluted in 100-μL Tris buffer (50mM Tris, 50mM MaCl2, pH=8.0) for digestion in sm-FRET experiments. Dynamics of the digested BamHI–HJ was obtained 20min later after an addition of BamHI. Here 0.8% (w/v) glucose, 1-mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.04-mg/mL catalase and 2-mM Trolox were involved as oxygen scavenger system.54,55

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Intrinsic dynamics of HJ with the BamHI restriction site (BamHI–HJ)

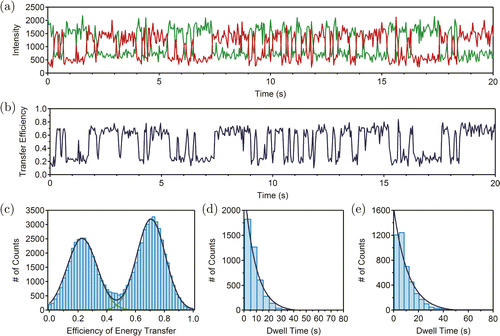

We first used sm-FRET to study the intrinsic dynamics of the newly designed BamHI–HJ containing five strands and longer X- and R-arms. A typical trace of sm-FRET is shown in Fig. 2(a). Cy3 signal (green) and Cy5 signal (red) hopped stochastically between the states of low or high intensity. The efficiency of energy transfer Ewas calculated by Eq. (1) :

Fig. 2. (Color online) (a) Typical traces of sm-FRET experiments. Green and red traces refer to Cy3 and Cy5 signals, respectively. (b) The dependence of efficiency of energy transfer on time. (c) The efficiency of energy transfer distribution of BamHI–HJ. Green curves are Gaussian fittings and dark blue curve is the sum of green curves. (d) The histogram for the dwell time at the “isoII” state. Dark blue curve is exponential fitting. (e) The histogram for the dwell time at the “isoI” state. Dark blue curve is exponential fitting. The data in (a)–(e) were collected in the absence of BamHI.

| Transfer efficiency | Transition rate (s−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BamHI–HJ | isoI | 0.23 | 0.107 |

| isoII | 0.71 | 0.085 | |

| Digested BamHI–HJ | isoI | 0.24 | 0.160 |

| isoII | 0.68 | 0.125 | |

| Original HJa | isoI | 0.2 | 5.7 |

| isoII | 0.6 | 6.1 |

3.2. Dynamics of the digested BamHI–HJ

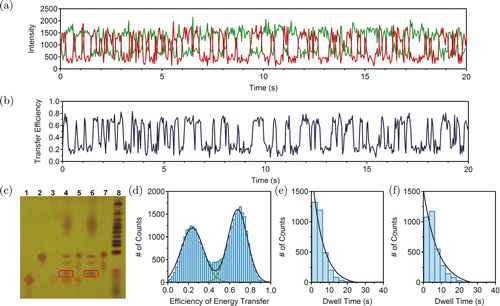

Before the sm-FRET experiments, we examined the efficiency of BamHI digestion in bulk using the PAGE gel. We constructed a complex of r-strand and x-strand following the similar protocol for HJ. This complex and BamHI–HJ were incubated with BamHI, respectively, for 1h before being analyzed using denatured PAGE. As shown in Fig. 3(c), both the digested BamHI–HJ (lane 4) and the digested complex (lane 6) had one additional band (red box), compared to the original BamHI–HJ (lane 5) and the complex (lane 7). This confirmed that the extended X-arm in BamHI–HJ can be effectively digested by BamHI. Next, we studied the dynamics of digested BamHI–HJ using sm-FRET. A typical FRET trace is shown in Fig. 3(a). The transfer efficiency hopped more quickly with shorter dwell time after BamHI digestion of the X-arm [Fig. 3(b)]. The distribution of transfer efficiency is also a clear bimodal distribution [Fig. 3(d)] and the double-Gaussian fitting yielded the efficiencies of 0.24 for “isoI” state and 0.68 for “isoII” state. The transfer efficiency of each state did not change much, compared to that of each state before digestion. The duration time of each state was used to create the histograms. The exponential fitting yielded the transfer rates of 0.160s−1 and 0.125s−1, for “isoI” to “isoII” and “isoII” to “isoI”, respectively [Figs. 3(e) and 3(f)]. The dynamics is summarized in Table 1. Note that the transfer rates for “isoI” to “isoII” and “isoII” to “isoI” increased by 50% and 47%, respectively, after BamHI digestion, suggesting that the dynamics of HJ can indeed serve as a reporter for the action of BamHI.

Fig. 3. (Color online) (a) Typical traces of digested BamHI–HJ. Green and red traces refer to Cy3 and Cy5 signals, respectively. (b) The time trajectory of the FRET efficiency. (c) The denatured PAGE results of BamHI digestion of HJ. Lane 1: h-strand, lane 2: r-strand, lane 3: biotin strand, lane 4: BamHI–HJ digested by BamHI, lane 5: BamHI–HJ only, lane 6: the complex of r-strand and x-strand digested by BamHI, lane 7: complex of r-strand and x-strand only and lane 8: low molecular weight DNA ladder (N3233L, New England BioLabs). (d) The efficiency of energy transfer distribution of BamHI–HJ after BamHI digestion. Green curves are Gaussian fittings to the two peaks and dark blue curve is the sum of the two Gaussian fitting curves. (e) The histogram for the dwell time at the “isoII” state. Dark blue curve is the exponential fitting. (f) The histogram for the dwell time at the “isoI” state. Dark blue curve is exponential fitting. The data in panels (a), (b) and (d)–(f) were collected after the digestion of BamHI.

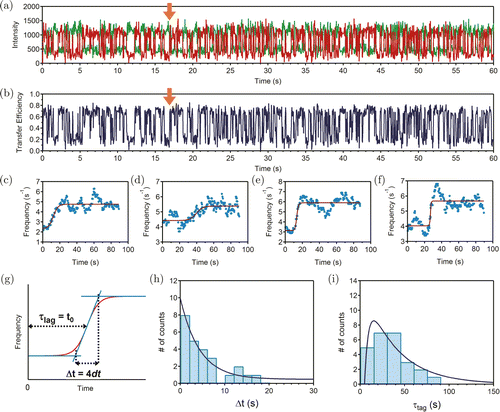

3.3. Direct observation of BamHI digestion based on the HJ dynamics

As mentioned above, the transition rates of the two states both rose after the BamHI digestion. Statistically, the turnover between the two states will become faster. Thus, we define the average turnover frequency, f, which is equal to the average number of turnovers per second in few seconds, as a measurable quantity to distinguish the undigested and digested BamHI–HJ. As shown in Figs. 4(a) and 4(b), the signal jumped from one to another more frequently after BamHI was added to the system at about 16s (marked by orange arrow). We calculated the average turnover frequency in a time span of 10s. The frequency–time curves were fitted with the Boltzmann function shown in Eq. (3) :

Fig. 4. (Color online) (a) Typical trace and (b) transfer efficiency during the BamHI digestion process. The orange arrow shows the moment when BamHI is added. (c)–(f) Four representative traces of the turnover frequency. BamHI was added at time 0. (g) Fitting scheme of panels (c)–(f). Here Δt is the time interval for the enzyme to finish the digestion reaction and τlag is the time needed from the addition of BamHI to the midpoint of Δt. (h) Histogram of the time span for each transition (Δt). Dark blue curve is exponential fitting. (i) The distribution of the lag time (τlag). Dark blue curve is the fitting to Eq. (6).

As the lag time, τlag, is the combined time for binding and digestion processes, the probability of τlag for the serial events at the single-molecule level can be described as shown in Eq. (6) (Ref. 56) :

4. Conclusion

In summary, we developed a HJ-based platform to study the activity of restriction endonucleases at the single-molecule level using single-molecule FRET. This method allows the activity of different restriction endonucleases to be measured without extra work to change the fluorescent-labeled enzymes or substrates. Using BamHI as the representative example, we showed that both the enzyme-binding and the substrate-release events can be observed based on the distinct dynamics of HJ at the corresponding states. Since this new tool greatly simplifies the single-molecule studies of DNA-binding enzymes, we anticipate that it can be broadly applied to study more complicated and important enzymes and provides unprecedented information for the understanding of their functions.

Conflict of Interest

We have no conflict interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

Xin Wang and Jingyuan Nie contributed equally to this work. The authors greatly appreciate the financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 21522402, 11674153, 11374148, 11334004 and 21771103), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. 020414380070, 020414380050 and 020414380058), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20160639) and the Shuangchuang Program of Jiangsu Province.