Fast fluorescence lifetime imaging techniques: A review on challenge and development

Abstract

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) is increasingly used in biomedicine, material science, chemistry, and other related research fields, because of its advantages of high specificity and sensitivity in monitoring cellular microenvironments, studying interaction between proteins, metabolic state, screening drugs and analyzing their efficacy, characterizing novel materials, and diagnosing early cancers. Understandably, there is a large interest in obtaining FLIM data within an acquisition time as short as possible. Consequently, there is currently a technology that advances towards faster and faster FLIM recording. However, the maximum speed of a recording technique is only part of the problem. The acquisition time of a FLIM image is a complex function of many factors. These include the photon rate that can be obtained from the sample, the amount of information a technique extracts from the decay functions, the efficiency at which it determines fluorescence decay parameters from the recorded photons, the demands for the accuracy of these parameters, the number of pixels, and the lateral and axial resolutions that are obtained in biological materials. Starting from a discussion of the parameters which determine the acquisition time, this review will describe existing and emerging FLIM techniques and data analysis algorithms, and analyze their performance and recording speed in biological and biomedical applications.

1. Introduction

Fluorescence microscopy has found broad applications in biological imaging because it is, within reasonable limits, noninvasive, nondestructive, extremely sensitive, and delivers both structural and functional information of the object under investigation. With the help of fluorescence labeling and transfection techniques for biological systems, fluorescence-intensity data can be obtained over three spatial dimensions, the wavelength, and the polarization of the light. However, data derived from the fluorescence intensity are easily affected by variation in excitation intensity, variable probe concentration, photobleaching, and instrumental effects like different focusing, detector gain, or misalignment. Performing quantitative measurements based on intensity alone is therefore difficult. Moreover, it is also difficult if not impossible to distinguish different fluorescent probes with very similar fluorescence spectra, and different fractions of a fluorophore in different states of interaction with its molecular environment.

The information obtained from biological samples is dramatically improved by adding the fluorescence lifetime as an imaging parameter.1,2 Fluorescence lifetime is the reciprocal of the sum of rate constants of various de-excitation processes, including fluorescence emission and nonradiative processes. Therefore, in contrast to the fluorescence intensity, fluorescence lifetime is a property of the fluorescent molecules and their interaction with the molecular environment. Consequently, fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) is nearly independent of the above factors.3,4,5,6,7,8,9 It can thus be conveniently used to achieve quantitative measurements and to distinguish different probes with similar fluorescence spectra. Importantly, according to the relationship between fluorescence lifetime and the environment around fluorescent molecules, FLIM technology can favorably be used to quantitatively measure various biochemical parameters in the microenvironment,6 such as oxygen content,5,10,11 pH,12,13 metabolic state,10,14,15 viscosity,16,17 solution hydrophobicity, ion concentrations,18,19 quencher distribution, temperature,20 and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) efficiency.21,22,23,24 Therefore, FLIM has played an increasingly important role in the biomedical field in the past two decades.

Understandably, there is a large interest in obtaining FLIM data in an acquisition time as short as possible. Often the demand for fast FLIM just originates from the desire to finish a given experiment in a shorter period of time, in other cases, there is the need for dynamic imaging of fast moving cells and organelles, vesicle trafficking in live cells,25 and dynamic changes in ion concentrations,26,27 metabolic state,28,29 or interactions between proteins.30,31 As a consequence, there is currently a run toward faster and faster FLIM techniques with a steeply increasing number of publications. There are FLIM techniques recording in the time domain and in the frequency domain, scanning techniques and wide-field techniques, and analog-recording and photon counting techniques.4,32 Different combinations are competing in acquisition speed. However, other parameters such as exposure and photostability of the sample, photon efficiency, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), pixel numbers, time resolution, image quality, depth resolution, capability to resolve multi-exponential decay functions, and, most importantly, suitability for different applications need to be fully considered. In reality, it is often the photostability of the sample which limits the speed. In most cases, faster acquisition can thus only be achieved by simultaneously increasing the photon efficiency.

This paper is an attempt to give an overview on currently used and emerging FLIM techniques and discuss their acquisition speed in the context with other performance parameters and typical applications.

2. Parameters Determining the Acquisition Speed of FLIM

2.1. Desired SNR

The SNR of FLIM depends on the number of photons per pixel .33 Ideally, the SNR of the fluorescence lifetime is

Assuming other conditions invariant, decreases with decreasing acquisition time. Consider the quadratic relation between the desired SNR and , a slight relaxation in the SNR requirements, therefore has a large impact on the recording speed. For scanning techniques, the number of pixels should also be taken into account. For example, a -pixel image needs 64 times more photons and thus 64 times longer acquisition time than a -pixel image.

2.2. Photon efficiency of the technique

It does not mean that any lifetime-detection technique automatically reaches the ideal SNR given by Eq. (1). The performance of a technique is described by the “photon efficiency,” which is the ratio of the number of photons ideally needed to reach a given SNR divided by the number of photons needed by the technique under consideration. Therefore, the time needed to obtain a FLIM image of a given SNR (and a given number of pixels for scanning techniques) scales reciprocally with the photon efficiency.

Different FLIM techniques vary in photon efficiency. FLIM techniques based on time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) reach a photon efficiency close to one. Techniques based on sliding a time gate over the decay function have lower photon efficiencies. The photon efficiency is also low for techniques that construct images from differences of photon numbers, such as structured-illumination and compressed-imaging techniques.33,34,35,36

2.3. Collection efficiency of optics

The collection efficiency of the optics directly influences the number of photons detected and thus the acquisition time needed to reach a given SNR. The collection efficiency is proportional to the square of the numerical aperture (NA) of the objective lens. In microscopy, there is usually no problem to use lenses of in air or to 1.3 in water or oil. For macroscopic imaging systems and endoscopes, the NA is much smaller, and so is the collection efficiency. Low NA also causes a problem with rotational depolarization. The laser is polarized, and excites preferentially molecules which have their dipoles in parallel with the excitation. Over the fluorescence decay, the molecules rotate away from the initial orientation. Unless all spatial directions of polarization are detected at the same efficiency, the rotational depolarization distorts the measured fluorescence decay. The rotation effect cancels for high-NA objective lenses because they effectively excite and detect from the entire half-space at the objective side.5,37 It does not cancel for low-NA lenses, however, because these do not detect photons polarized in parallel with the optical axis, i.e., one of the two perpendicular components is missing. The problem is normally solved by placing a polarizer in the detection path under the “magic angle.” The polarizer then corrects the ratio of parallel to perpendicular components. The magic angle depends on the NA.38 In any case, the polarizer suppresses photons and thus decreases the collection efficiency. The NA of the collection optics should therefore be kept as high as possible.

2.4. Photon rate from the sample

Even a FLIM system with unlimited count rate cannot yield images within a short acquisition time if the sample does not deliver the required photon rate. Technically, there are two ways to increase the photon rate: Increasing the fluorophore concentration and increasing the excitation power. The first one is normally not an option for molecular imaging in live systems for that fluorophore concentrations in these systems must remain at a noninvasive level. Moreover, measurement of molecular parameters implies that the fluorophores are attached to specific molecular targets in the cells. The effective fluorophore concentration is thus low.

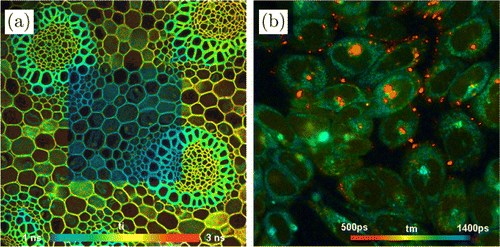

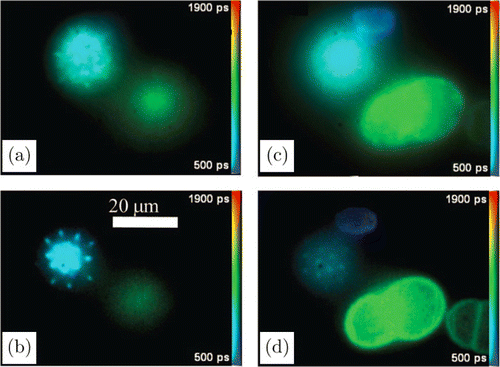

The second option — increasing the excitation power — leads to photobleaching and photodamage. Examples are shown in Fig. 1. In the left panel, the central area of the field of view was scanned with a 405-nm laser for 1min prior to FLIM imaging, using a relatively high power (10 times the imaging power in terms of count rate). It clearly shows that photobleaching has occurred, and the lifetimes in the area have massively changed. It should be noted that photobleaching not only has an impact on the intensities and lifetimes, but also produces radicals, which cause photochemical stress to the cells. Attempts to reduce photobleaching by increasing the fluorophore concentration do not reduce the amount of radicals produced, and consequently, the photochemical stress to the cells. In the right panel of Fig. 1, spots of increasing size and extremely short lifetime in an NADH image of live cells show severe photodamage, which occurred within 20s upon exposure to two-photon excitation at 750nm even if the count rate is only 1/20 of the situation in the left panel. In these cases, the only way to achieve short acquisition time is to use a technique with high photon efficiency and to optimize the optical system for collection efficiency.

Fig. 1. Examples for illustrating photobleaching and photodamage. (a) FLIM image of Convallaria, region in the center scanned with a 405 nm laser (107 photons per second) prior to imaging (106 photons per second). Photobleaching has changed the fluorescence lifetime in the pre-scanned area. (b) NADH FLIM image of live cells, two-photon excited ( photons per second). In the bright red spots, photodamage has occurred, revealing itself by an ultrafast decay component. With permission from Ref. 37.

2.5. Desired time resolution

The lifetimes of decay components in biological samples typically range from 5ns down to about 100ps. Short lifetimes should not only be detectable, but also be quantifiable in the presence of decay components of longer lifetime. In time-domain recording, this requires an instrument-response function (IRF) width on the order of 100ps or shorter, and at least 5 times finer time bin width for the decay curves recorded. If a technique does not deliver the required time resolution, short lifetimes can still be detected, but the photon number and thus the acquisition time needed increase dramatically.

2.6. Accuracy for obtaining desired information

In most applications, the fluorescence decay curves are sums of several exponential components. The desired information is in the composition of the decay, i.e., the amplitudes and lifetimes of the components. What is thus needed is the complete fluorescence decay curve. A single-exponential lifetime may be enough to distinguish areas with different fluorophores in a sample, but it fails if several fluorophores are present in the same pixel. Molecular imaging applications aim at the identification of different fractions of the same fluorophore in different states of interaction with the molecular environment. The options for molecular FLIM without multi-exponential decay capabilities are therefore limited.

Moreover, exciting and recording fluorescence in the entire depth of a sample may yield high count rates and thus short acquisition times, but the information obtained is not the desired one. What is needed is a FLIM image of a defined cross-section through a cell or a piece of tissue, with fluorescence decay data from defined organelles without contamination from above and below.

2.7. Overall consideration

Technology development is currently focusing mainly on recording speed. The recording speed a FLIM technique can reach is a function of the parameters described above. First of all, the sample must be able to feed the system with a sufficiently high photon rate. How high this rate has to be depends on the desired acquisition time, the number of pixels, the expectations for the lifetime resolution and accuracy, and the photon efficiency of the technique.

For a sample that delivers a photon rate that does not exceed the counting capability of a FLIM system, a high-efficiency technique therefore records faster than a low-efficiency technique. For samples which deliver high count rates, the relation can reverse: If the high-efficiency technique is not fast enough to record all photons, a low-efficiency technique with unlimited count rate can be faster. However, the requirements for the stability of the sample increase nonlinearly: The sample not only has to deliver the photon rate to obtain higher speed, it also has to deliver additional photon rate to compensate for the lower photon efficiency. Technology development should therefore aim first at efficiency, and then at recording speed.

Certainly, the maximum acquisition speed a FLIM technique can reach also depends on a number of instrumental details. Detectors may need time to recover after the detection of a photon, the recording device may need time to process the photon, time may be needed to read out the data from the recording device, and to create a lifetime image from the recorded data.

Details for commonly used techniques will be discussed in the following section.

3. Improving Acquisition Speed in Different FLIM Techniques

3.1. Fast FLIM based on TCSPC

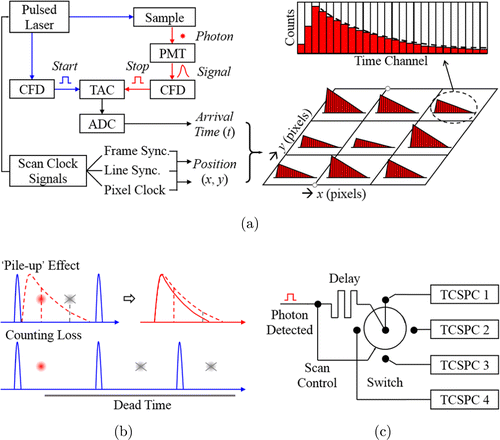

TCSPC-FLIM is commonly used in biological applications. It combines high time resolution and high photon efficiency.5,33,34 As shown in Fig. 2(a), the sample is repeatedly scanned by a high-repetition rate pulsed laser beam, and a detector detects single photons of the fluorescence signal returning from the sample. Each photon is characterized by its time in the laser pulse period and the coordinates of the laser spot in the scanning area in the moment of its detection. The recording process builds up a photon distribution over these parameters. The result can be interpreted as an array of pixels, each containing a fluorescence decay curve in a large number of time channels.

Fig. 2. (a) Principle of TCSPC-FLIM. CFD: constant fraction discriminator; TAC: time-to-amplitude converter; ADC: analog-to-digital converter; Sync.: synchronization. Photon distribution , , is obtained and converted into FLIM image with data analysis. (b) Illustration of “pile-up” effect and counting loss in TCSPC-FLIM. The dash line indicates the real decay, the solid line measured. (c) Illustration of fast-acquisition FLIM with parallel TCSPC modules.

3.1.1. Instrumental limitations and improvement

The “pile-up” effect and counting loss

As a serious drawback of TCSPC, it is often stated that the technique can record only one photon per signal period. If the light intensity is high, a possible second or third photon arriving in the same excitation pulse period with the first one is lost, as shown in Fig. 2(b). The result is a distortion of the recorded signal waveform. A derivation of the systematic error in the detected fluorescence lifetime caused by “pile-up” effect has been given.37,39 At a photon detection rate of 10% of the excitation pulse rate, the error is about 2.5%, which is quite small and acceptable in many applications. However, the error increases with the photon detection rate. Therefore, to avoid this “pile-up,” one should keep the photon detection rate at a low level, which means the recording speed is limited to some extent.

TCSPC reaches a timing accuracy for the individual photons on the order of a few picoseconds (ps). This accuracy comes at a price: The processing of each photon takes time. During the time a photon is processed, no other photon can be recorded. The processing time is therefore also called “dead time.” The loss of photons in the dead time is called “counting loss,” which causes a nonlinearity in the intensity scale of the FLIM image. Counting loss becomes notable at a photon rate of about 10% of the reciprocal dead time, and reaches 50% at 50% of the reciprocal dead time.37,39

What happens at high count rates depends on the ratio of the fluorescence lifetime and the dead time. If the dead time is longer than the fluorescence lifetime, normal “pile-up” occurs. If the dead time is shorter than the fluorescence lifetime, the effect is counting loss. The amount of loss depends on the count rate in the moment of the detection of photons. The peak count rate in the pulse is about twice the average count rate multiplied by the ratio of the signal period and the lifetime. Assuming an average photon rate of 10MHz, a signal period of 20ns and a lifetime of 4ns, the peak count rate is 100MHz. That means a photon rate of 10MHz is about the limit for distortion-free recording for a system with 1ns dead time.

TCSPC-FLIM with low-dead-time TDC principle

The heart of any TCSPC device is the electronics for the conversion of the times of photons into a digital data word. Standard TCSPC-FLIM devices use either a time-to-amplitude converter-analog-to-digital converter (TAC-ADC) principle or a time-to-digital converter (TDC) principle. The classic TAC-ADC principle converts the start–stop time first into the amplitude of an analog signal and then into a digital data word. The principle delivers extremely high resolution: The time-channel width can be as small as 0.2ps and the electrical IRF width as short as 3 ps. With fast hybrid detectors, a system IRF width of less than 20ps is reached; with superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs), the IRF width can be as short as 2.7ps.40

The TDC principle uses the delay in a chain of logic gates as a timing reference. It delivers a time channel width down to a few ps and an IRF width of about 20ps. This principle can be made very fast in terms of recording speed. It is even possible to determine the times of several photons for each laser pulse,41 which can be stated as multi-stop TDC.

A FLIM system based on a low-dead-time TDC has been introduced.41 It has a dead time of less than 1ns and a time-channel width of 250ps. A hybrid photomultiplier tube (PMT) is used as a detector. Hybrid PMTs have a single-electron response of about 800ps. It can thus be expected that the system has an overall dead time of about 1ns. According to Ref. 41, an image rate of 10 frames per second (fps) can be reached for recording FLIM images. The system has been demonstrated by recording FLIM images of moving fluorescent beads at a resolution of pixels and at a rate of 3 fps. Tyndall et al. utilized a similar multi-channel TDC in their design of a miniaturized high-throughput lifetime sensor.42 Up to 8 photon events during each excitation period could be recorded.

Also, devices on multi-stop TDCs have a dead time. Reported dead times for the electronics are in the range of 1ns to 10ns. Short dead time of the electronics can be exploited only if the dead time of the detector is shorter. The dead time of a detector is at least as long as the width of its single-electron response.37 It is a few ns for conventional PMTs, a few 10ns for single photon avalanche diodes (SPADs), and about 1ns for hybrid detectors. Only SNSPDs have a single-photon response of less than 200ps.

Disregarding the difficulties, FLIM with multi-stop timing has been demonstrated to deliver excellent images of dynamic samples. Of course, also multi-stop systems can achieve fast acquisition only if the sample delivers a sufficiently high photon rate. The realm of the systems is therefore discrimination of fluorophores of different lifetime in samples stained with high fluorophore concentrations. For applications like metabolic imaging by NADH/FAD detection or protein interaction measurement by FLIM-FRET, where the count rates delivered by the sample are usually no more than 500kHz, multi-stop timing FLIM would not be a best choice.

Fast-acquisition FLIM with parallel TCSPC modules

The maximum count rate of a TCSPC-FLIM system can be further increased by splitting the light into several detector channels and parallel TCSPC modules. FLIM by a TCSPC system with four parallel channels and eight spectrally separate channels have been described.43,44 The acquisition time for eight -pixel images in separate spectral channels was 5s.

A fast-acquisition FLIM technique introduced recently45 uses a single detector, the photon pulses of which are distributed into four parallel TCSPC modules, as shown in Fig. 2(c). The pulses are distributed by a switch that is controlled by the photon pulses themselves. The data of the four modules are combined into a single FLIM dataset. The TCSPC modules are running the normal TCSPC FLIM process.5,37,39

Pile-up occurs only if more than four photons are detected in one laser pulse period. Dead time effects in the TCSPC modules are smaller than for a system with four detectors because the switch regularizes the photon arrivals. The effect of detector and discriminator dead time is the same as for FLIM systems with fast time-conversion principles.

Since the system is using normal TCSPC modules, there is no need to trade time resolution or time channel width against acquisition speed. The IRF width with fast hybrid detectors is less than 25ps,45,46 and the time-channel width can be made shorter than 1ps.37 The number of time channels is large enough for multi-exponential decay analysis.37,47,48 Images down to acquisition time of 100ms for pixels and 250ms for pixels were presented.46 In fact, the minimum acquisition time is rather limited by the speed of the scanner than by the TCSPC system. Double-exponential decay analysis of images with pixels recorded in 4s was demonstrated.48

Liu et al. proposed a system with confocal scanning, seven SPAD detectors and seven parallel TCSPC channels.49 With the pixel dwelling times of 0.2ms to 0.5ms reported,50 the acquisition time for the entire image is in the range of tens of seconds.

Commercial TCSPC-FLIM system usually has two or more fully parallel channels. These are normally used to record in separate wavelength or polarization channels.51,52 The channels can, however, also be used in parallel to increase the maximum count rate. Recording of chlorophyll transients in two parallel channels has been demonstrated previously.52,53 Time-series recording of -pixel images in two parallel channels was performed at an acquisition time of 0.5s per image.

3.1.2. Saving acquisition time by improving scanning

The optical imaging technique used in combination with a special FLIM technique has a large influence on the performance of a FLIM system. Basically, fluorescence lifetime imaging can be performed by wide-field illumination and wide-field detection, or by scanning the sample with a focused laser beam and detecting the photons with a point detector. FLIM based on scanning, such as typical TCSPC-FLIM is able to deliver images from a defined focal plane inside a sample,54 avoiding the influence of out-of-focus signals37,55 and thus having optical sectioning capability. Another advantage is the applicability of multi-photon excitation,56,57 being able to record images from focal planes deeply within biological tissues. However, one big disadvantage of scanning is the limitation in imaging speed. Even the fastest FLIM system cannot record faster than the scanner can scan the sample. The frame times of the commonly used galvanometer scanners range from about 40ms to 1s, depending on the number of lines. Faster scan rates can be obtained from resonance scanners, polygon scanners, and acousto-optical deflectors (AODs). It should be noted that this comes at a price: Resonance scanners have a fixed scan rate, and polygon scanners have a fixed size of the scan field.

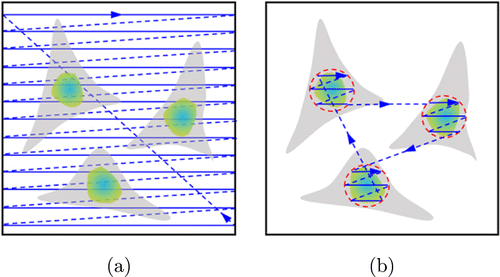

An easy way to increase the speed of FLIM image acquisition is to scan only the regions of interest (ROIs) in a wide field of view. Qu’s group at Shenzhen University has combined AOD scanning technology with TCSPC-FLIM. With AOD technology, fast addressable scanning and FLIM imaging of arbitrary ROIs in biological samples is achieved58,59,60 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Comparison of (a) raster scanning with galvanometer scanner and (b) addressable scanning with AOD. If the ROIs (e.g., cell nuclei in the illustration) are discrete, the multiple-ROI scanning will save much of the acquisition time.

To achieve faster recording of TCSPC-FLIM, it has been attempted to scan the sample with several beams and project the photons from the individual foci to separate detectors or separate channels of a multi-anode PMT. An instrument of this type has been described by Kumar et al.61 Multi-photon excitation with 16 beams were used, and the fluorescence from the luminescent spots was projected on the 16 input stripes of the tube in the detector. The data from the stripes were recorded simultaneously by a routing function and these stripes were later combined into a complete image.

A multi-beam scanning system with an SPAD array has been described by Poland et al.62 The excitation beam of a femtosecond Ti:Sa laser is split into beams by a spatial light modulator (SLM). The two-photon-excited emission from the illuminated spots is projected on the -pixel SPAD array. Each of the pixels of the SPAD array has a TDC and provides photon times with a time-channel width of about 50ps. The maximum count rate of the system is 16MHz, i.e., about four times higher than the reasonable limit of normal TCSPC-FLIM. This was due to limitations in the readout circuitry of the SPAD array. An improved version of the readout circuitry has been developed later.63

For each position of the scan, the setup delivers single-photon data for positions. Pixels between these positions are obtained by scanning, e.g., an scan produces an image of pixels. FLIM images of MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells transfected with EGFP, acquired for 0.5s and 5s, respectively, were obtained.51 The system has also been applied to dynamic imaging of FRET processes between the fluorescent proteins EGFR-EGFP and Grb2-mCherry in live cells, with a single-frame image acquisition time of 10 s (image field of view of m).62,64,65

The SLM can also be used to manipulate the depth in which the individual beams come to a focus. This way, FLIM Z stacks can be acquired without the need of shifting the microscope lens axially. The principle and an application to FRET imaging have been described recently.66

3.1.3. Temporal mosaic recording with triggered accumulation

A technique termed “temporal mosaic FLIM” is another way to detect fast changes in the fluorescence decay behavior of a sample. The FLIM system records a series of FLIM images into subsequent elements of a large data array (a “mosaic” of FLIM data) after a lifetime change is induced by some external stimulation to a sample.37 If each image is recorded in just one frame, the series will be as fast as the scanner can go. The greatest strength of this technique is that it is still effective when the sample does not deliver enough photons within one scan. The stimulation can be applied to the sample periodically, and with every new stimulation, the recording will run through all elements of the data array to accumulate photons.5,18,37 The result is a fast time series, the SNR of which no longer depends on the scanning speed, but depends on the total acquisition time for a given photon rate. In this way, the frame rate at which a dynamic process is resolved is limited by the scanner, not by the TCSPC process. A FLIM recording of the Ca transient in live neurons is shown.37 The number of pixels in an individual image element is , and the scan time per image element was 38ms. External stimulation can also be bleached in the technique of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). A simultaneous combination of FRAP-FLIM and time-resolved anisotropy has been reported, using a similar temporal mosaic recording method.67,68

A way to resolve even faster dynamic lifetime effects is to combine the TCSPC recording with line scanning, which is also called fluorescence lifetime-transient scanning (FLITS).18,39,69 The fastest line times for galvanometer scanners are in the range of 1ms, consequently transient effects can be resolved down to about 1ms. The application to Ca imaging in live neurons has been shown.69

3.1.4. Wide-field TCSPC

To combine the advantages of scanning-based FLIM and high frame rate of wide-field imaging mode, wide-field TCSPC-FLIM has been proposed.63,70

Wide-field TCSPC with position-sensitive detectors

Wide-field TCSPC-FLIM can be performed with position-sensitive microchannel-plate (MCP) detectors. For every photon, the detector delivers a pulse that marks the detection time, and several signals from which the position of the photon on the photocathode is derived. The associated electronics build up a photon distribution over the times and the positions of the photons.71

There are two ways to obtain the position information. One way is to couple the single-photon pulses into two crossed delay lines at the detector output. The position is then derived from the arrival times of the photon pulses at the four outputs of the delay lines.37,71 The second way is to derive the position from the electric charge of the individual photon pulses at several outputs of a structured anode.72,73

For these techniques, the position measurement is a relatively complicated and time-consuming procedure. Moreover, the photon times are measured in a single TCSPC channel. The maximum count rate and the acquisition speed of a wide-field TCSPC system are therefore no higher than for a TCSPC-FLIM system with scanning. On the positive side, the photon efficiency is close to one, as it is typical for TCSPC. In applications where the peak excitation power has to be kept low, wide-field TCSPC therefore reaches the shortest possible acquisition times. Other applications of wide-field TCSPC-FLIM are microscope techniques which cannot efficiently be performed by scanning, such as light-sheet microscopy, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, or super-resolution microscopy based on switchable fluorophores.

Wide-field TCSPC-FLIM with SPAD arrays

SPADs are based on avalanche photodiodes (APDs) which are biased above the breakdown voltage (sometimes called “Geiger mode”). When a photon is absorbed in the active volume, an electron–hole pair is generated, which in turn causes an avalanche of additional pairs and an easily detectable current pulse. The diodes are thus suitable as single-photon detectors.74

In the last decades, arrays of SPADs with integrated TDCs have been developed.63,75,76,77,78,79,80,81 The number of pixels for typical devices is or , with the time channel width of the TDCs in the range of 50ps to 120ps. A device with pixels shared 1728 TDCs has recently been developed by Lindner et al.82 Henderson et al. have reported a SPAD array with TDCs in every pixel.83

The devices normally produce a data word for every photon, providing spatial and temporal information for the buildup of a photon distribution. Since the data transfer rates are in the range of Gigabits per second, photon rates of hundreds of MHz can be processed, and consequently millisecond acquisition times and correspondingly high image rates can be reached. Image rates up to 100 fps have been reported. However, because of the low pixel numbers, the effective imaging speed is still in the range of normal TCSPC-FLIM. For example, an image rate of 100 fps for pixels is equivalent to an image rate of 6.25 fps for pixels.

The devices still have a few shortcomings. Except for the insufficient pixel numbers for most FLIM applications, the IRF width is often in the range of several 100ps, and the fill factor is low. For example, the array developed by Lindner et al. reported a fill factor of 28%,82 while Henderson et al. quoted a fill factor of 13%, and increased to 42% by microlenses.83 The low fill factor results from the fact that chip space is needed for the TDCs, and that the SPADs have to be spatially separated to avoid cross-triggering. It can be expected, however, that these parameters will quickly improve. It should be noted that the recording process in SPAD arrays is more efficient than in gated image intensifiers (see Sec. 3.2.1), especially if the entire decay profile is to be recorded. The TDCs of the SPAD array record data in all time channels in parallel whereas the image intensifier sequentially shifts a gate over the decay functions. Temporal parallel recording may partially compensate for the efficiency loss by the low fill factor.

A FLIM system with a -pixel SPAD sensor with internal TDCs has been described by Krstajic et al.63 The collected fluorescence from the sample is separated and projected both on a normal CCD camera and the -pixel SPAD array. In practical use, an image is first acquired with the CCD camera, then an ROI is selected in the CCD image, and a FLIM image or a time series of FLIM images of this region is acquired with the SPAD array. A typical result is shown in Fig. 4. The acquisition time was 3s, resulting in an average of 33,000 photons per pixel. Assuming that reasonable lifetime accuracy can also be obtained from 300 photons per pixel, reasonable-quality images could also be obtained within 30ms.

Fig. 4. Example results from a wide-field FLIM system using a -pixel SPAD array with internal TDCs. Left panel: Intensity image of a wide field of view, acquired by a normal CCD camera. Right panel: -pixel FLIM images of the three marked ROIs by the SPAD array. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 63, OSA Publishing.

3.2. Fast FLIM by gated photon counting

The gated photon counting technique was the first time-domain FLIM technique that became commonly available. It is still one of the standard FLIM techniques in laser scanning microscopes.84,85,86,87,88 The technique counts the photon pulses of a high-speed detector into several parallel gated counters.89,90 The gates are controlled via separate gate delays. If the measured decay curve is completely covered by consecutive gate intervals, all detected photons are counted. The counting efficiency thus comes close to one.34 The counters can be made very fast. In practice, the count rates are only limited by the single-electron response of the detector. With the commonly used PMTs, peak count rates around 100MHz and average count rates of several 10MHz can be achieved. With these count rates — if available from the sample — acquisition times of less than 1s for -pixel images can be reached. The fluorescence decay time is derived from the photon numbers in the time windows.

The disadvantage of the technique is the relatively long gate duration (in practice ps) and the limited number of gate and counter channels (2 to 8). From the standpoint of signal theory, the signal waveform is undersampled, which cannot be reconstructed without assumptions about the signal shape. This is especially the case if the start point of the decay function in the first time window is not exactly known, and when the IRF of the detector is not negligible.39 Counting loss has the same influence on the results as described for FLIM with fast time-conversion principles.

Another time-gated photon counting technique is achieved by sequentially detecting in two or more time gates, by sliding a time gate over the time interval of the fluorescence decay, and the fluorescence signal detection is usually combined with wide-field imaging by a camera-like image sensor. Some performance-enhancing detectors have constantly emerged during the past decades, such as the gated image intensifiers or gated and modulated CCD image sensors. Because the data in all pixels are obtained simultaneously, the acquisition speed can be significantly higher than for scanning techniques in principle. However, there are also disadvantages. The obvious one is that there is no intrinsic depth resolution, so the out-of-focus signals, scattering in the sample, and fluorescence from the optics are hard to remove and greatly impair the image contrast.37,55 Combination with optical sectioning techniques is an attempt to overcome or mitigate this drawback.

3.2.1. Gated image intensifiers

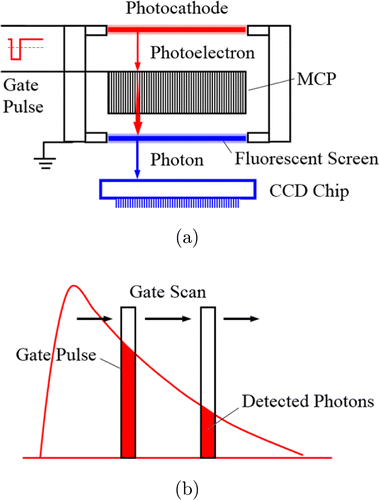

Image intensifiers are vacuum tubes containing a photocathode, a multiplication system for the photoelectrons, and a two-dimensional image detection system (Fig. 5(a)). MCPs are used for electron multiplication, offering a multiplication factor on the order of 106. With a gain this high, the sensitivity is on the single-photon level. Time resolution is obtained by gating the image intensifier. This is achieved by applying a gating pulse between the MCP and the photocathode.91,92,93,94 The fluorescence decay is sampled by taking consecutive images for different delays of the gate pulse (Fig. 5(b)).

Fig. 5. (a) Gated image intensifier. MCP: microchannel plate. (b) The fluorescence decay is sampled by taking consecutive images for different delays of the gate pulse.

The speed of the imaging depends on several parameters. On the one hand, all pixels of the image are recorded in parallel. On the other hand, the data points on the fluorescence decay curves are normally recorded sequentially. The recording speed thus depends on the number of points in time and, consequently, on the demands for the time resolution. In principle, the lifetime of a single-exponential fluorescence decay can be determined from only two images taken in two wide time gates. An instrument that simultaneously records in two time gates by projecting two images of different optical delay to the same image intensifier, which further saves acquisition time, has been described by Agronskaia et al.95,96 The authors demonstrated it for recording Ca transients in contracting cardiomyocytes. Image series were obtained at 50 fps and 100 fps, and the Ca changes during the contractions were resolved. A segmented gated intensifier allowing simultaneous acquisition of four time gates after one excitation pulse was reported by Elson et al.97 However, it should be noted that the lifetime data of all pixels of the images were combined to obtain a sufficient SNR.

Problems can occur if precise multi-exponential decay analysis is needed. In that case, at least 100 data points in time are required. This not only slows down the acquisition, but also results in poor photon efficiency. For every gate position, only the photons within the gate pulse are used, the rest is lost. Assuming a gate of 100 ps width and a 10ns observation time interval sampled in 100 steps, the efficiency would be only 10. An increase of the efficiency can be obtained by using wide gate pulses and overlapping gate scanning.98 However, the effective IRF then becomes as wide as the gate pulse. Thus, an efficiency increase by a wide gate pulse is obtained only for decay times longer than the gate width. Increasing the excitation power may not compensate for the efficiency because of photobleaching and photodamage.

3.2.2. Gated and modulated CCD image sensors

Direct gating of a normal CCD image sensor was described by Mitchell et al.99 The device delivered lifetime images for decay times of 50 ns and slower. However, the repetition rate and the gate width were not sufficient for recording fluorescence lifetimes in the nanosecond and sub-nanosecond range. A CCD chip with integrated gating circuitry has been described by Seo et al.100 The device has four parallel gates with 0.8ns to 3ns width. The maximum readout rate is 45 fps for images of pixels.

CCD image sensors can also be modulated for frequency-domain techniques (see Sec. 3.5). Direct modulation of a CCD image sensor was described by Mitchell et al. in 2002.101 The problem was that a sufficiently high modulation frequency could not be reached. Recently, Raspe et al.102 used a modulated CCD camera for FLIM of Ca transients at a frame rate of 50 fps.

3.2.3. Combination with optical sectioning techniques

There are several techniques to overcome or mitigate the drawback of wide-field FLIM imaging. Depth resolution can be obtained by structured-illumination or compressed-imaging techniques. Temporal focusing is another novel way to obtain optical sectioning with wide-field excitation. Other solutions are based on a combination with scanning, e.g., Nipkow-Disk scanning or multi-beam multi-photon excitation.

Structured illumination

Optical sectioning by structured-illumination was introduced by Neil et al. in 1997.103 The technique is based on the insertion of a moving grid in the upper focal plane of a microscope. By extracting the modulated fraction of the light, images from an image plane conjugated with the plane of the grating are obtained. The combination with gated image intensifiers has been described by Cole et al.104 and by Hinsdale et al.105 The problem is that images have to be acquired for several lateral (for three-dimensional (3D) imaging also axial) positions of the grating. Moreover, image reconstruction from structured-illumination data involves calculation of differences between images for different grating positions. This massively decreases the SNR. Therefore, the photon efficiency becomes low, and large photon numbers need to be acquired, with correspondingly long acquisition times.

Temporal focusing

Choi et al. used temporal focusing in combination with a modulated image intensifier.106 The beam of a Ti:Sa laser is split into several parallel beams of different wavelength. All beams are sent through different parts of the aperture of the objective. Due to their narrow wavelength intervals, the pulse width in the individual beams is larger than in the original beam. Each individual beam does not cause much excitation in the sample until it comes to focus with the other beams. In the focal plane, the beams combine again and yield a short pulse. Thus, although the laser illuminates the entire field of view, excitation occurs preferentially in the focal plane. The technique is possibly the fastest wide-field imaging technique with optical sectioning. However, the required laser power is in the range of several Watts, which would limit the use in biological imaging.

Nipkow-disk systems

Nipkow-disk,107,108,109 light sheet systems,110,111,112,113,114 and total internal reflection (TIR) illumination115 can inherently provide depth resolution. For the Nipkow systems described by Grant et al.107 and Görlitz et al.109 the acquisition times for pixels range from 1s for low-quality images recorded in two time gates and 30s for high-quality images sequentially recorded in eight time gates. A comparison of FLIM images recorded by a gated image intensifier with and without optical sectioning by a Nipkow disk is shown in Ref. 107 (Fig. 6). The technique has been used to study signaling in live cells.108 An acquisition time of 1s per image for acquisition into 10 time gates was used. However, the Nipkow-disk method uses single photon excitation, and as such also bleaches above and below the focal plane during imaging, which is detrimental for imaging 3D stacks.

Fig. 6. Conventional FLIM images of pollen grains from a gated image intensifier (a), (c) and images obtained by the same image intensifier with optical sectioning by a Nipkow disk (b), (d). Eight time gates, total acquisition time 4s. Adapted with permission from Ref. 107, OSA Publishing.

Multi-beam multi-photon scanning

Nipkow-disk techniques are restricted to one-photon excitation, which is not well suited to imaging of internal layers within biological tissue. Gated image intensifiers have therefore been combined with multi-beam multi-photon imaging.116 Multiple beams generated by a near-infrared femtosecond laser, which can easily reach deep tissue layers, are used to scan the sample. Due to parallel acquisition of fluorescence from many beams, the technique achieves shorter acquisition time than single-point multi-photon scanning. It should be noted that the image resolution and the image contrast are impaired by scattering on the way out of the sample, which therefore loses much of the ability of multi-photon scanning to obtain sharp images of deep tissue layers.

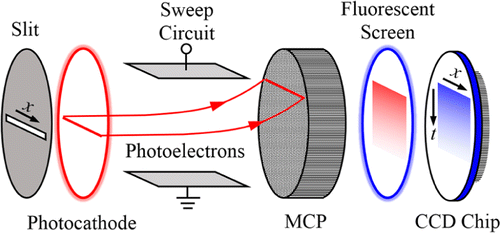

3.3. Streak camera system

A streak camera is based on an electron tube with a photocathode at the input, an electron-optical imaging and deflection system, and a fluorophore screen at the output (Fig. 7).117 Time resolution is obtained by applying a fast voltage ramp to the deflection system. The output pattern is recorded by a CCD camera.118 Modern streak cameras contain an MCP for electron multiplication. The gain is sufficient to reach a sensitivity down to the single-photon level.

Fig. 7. Principle of FLIM with a streak camera. Photons with different arrival times are deflected to different positions along the direction perpendicular to the slit.

A FLIM system based on a streak camera has been described by Krishnan et al.119 The streak camera was combined with a two-photon laser scanning microscope by projecting the individual lines of the scan on the input of the camera. This requires a special scanner that de-scans the image only in -direction. The time-resolved intensity pattern of the whole line was accumulated in the CCD camera and read out during each line flyback. The system has a temporal resolution of 50ps. The fluorescence decay is recorded into a sufficiently large number of time bins so that multi-exponential decay functions can be resolved. For high MCP gain, the photon efficiency can be expected to be close to one.

In principle, a streak camera-based FLIM system should be able to work at high intensities. The acquisition time is then only limited by the speed of the scanner. However, due to limitations of the trigger and deflection electronics, the instrument described works at a laser repetition rate of only 1MHz. The average laser power is thus very low, and so is the photon rate obtained from the samples. Compensating by higher laser peak power leads to higher-order excitation effects and sample damage.

Thompson et al.120 have applied compressed ultrafast photography (CUP) to FLIM measurement based on a streak camera. A high-speed CMOS camera captured each compression-coded image with a single exposure, and a compressed sensing (CS) algorithm was used to record the lifetime image. The authors present lifetime images of fluorescent beads and a cell stained with high dye concentration, achieving an acquisition speed of 100 fps (pixel number not given).120 Compressed-imaging is fast but has extremely low photon efficiency. Therefore, extremely high photon rates are required.

3.4. Time-domain analog-recording techniques

Analog-recording techniques consider the detector signal a continuous waveform, the temporal shape of which reflects the fluorescence decay function. The sample is scanned by a pulsed laser beam, the fluorescence is detected by a fast optical detector, and the detector signal is recorded by a fast digitizing device. Sometimes, simply, a fast digital oscilloscope is used. The signal waveforms for excitation pulses within one pixel are accumulated, then the result is read from the digitizer and assigned to the corresponding pixel.121 The process is repeated for all pixels in the scan area. An acquisition time of 1 s for an image size of pixels has been reported.121

A way around the fast digitizer has been shown.122 The authors use a low-pass filter behind the PMTs. The resulting signal shape can be sampled by a digitizer with 1 GS/s. Of course, the shape of the recorded signal no longer resembles the fluorescence decay. However, the delay between the centroid (or the first moment) of the signal and a reference signal from the laser represents the apparent lifetime of the fluorescence decay. Instruments of this type and corresponding applications are described by Ryu et al.122 The recording speed achieved was 3.7 fps, limited by the scanner (pixel number not given). Maximum image size was pixels.

To achieve faster scanning, Won et al. used a resonance scanner for the same recording system.123 This way, the acquisition rate was increased to 7.7 fps for -pixel images. Under these conditions, the photon rate at the detector was approximately 125MHz. By using a graphics processor unit (GPU) for image buildup, the image rate was increased to 13 fps for -pixel images.124

Theoretically, analog recording is free of “pile-up” and counting loss effects. Thus, there is no intrinsic limitation in photon rate or signal intensity. In practice, the recordable photon rate and thus the speed of the recording are limited by the linearity range and the maximum output current of the detector. The speed can also be limited by the fact that the pixel rate of the scan cannot be higher than the readout rate of the digitizer.

The problem of analog recording is the poor time resolution. Different from photon counting, the instrument response cannot be shorter than the single-photon response of the detector. For fast PMTs, the IRF width is on the order of 1ns to 2ns, for hybrid PMTs, it is about 800ps, and for MCP-PMTs, it is about 350ps. These IRF widths can be reached only if the digitizer has a bandwidth of at least 5GHz and a sample rate of more than 10GHz. The large width of the IRF, and unavoidable ringing and electrical reflections in the signal shape make it difficult to resolve multi-exponential decay profiles, especially when they contain components faster than 300ps.

3.5. Frequency-domain analog-recording techniques

Frequency-domain FLIM records differences in the phase and the modulation degree between a modulated or pulsed excitation and the fluorescence signal. These values translate directly into the fluorescence lifetime. The development of the technical principles dates back to the 1980s.125,126 FLIM is performed by scanning the sample and detecting the fluorescence by gain-modulated detectors. The modulation of the excitation light and the modulation of the detectors need not be sinusoidal.125,127 Pulsed excitation even yields higher photon efficiency.35 State-of-the-art frequency-domain systems therefore use high-frequency pulsed lasers.

Analog frequency-domain FLIM works up to high intensities, where single photon detection becomes impossible. Problems may occur at extremely low intensities, when the detector, on average, delivers less than one photon within the time interval of the phase calculation. What then happens depends on the details of the electronics used.

The photon efficiency of frequency-domain FLIM depends on a number of instrumental details. The best efficiency is obtained by using short laser pulses, and by modulating the detectors by square-wave signals. Moreover, it matters whether the detectors are really modulated in gain or rather in photon detection efficiency. Efficiency modulation suppresses a part of the photons and results in a sub-optimal SNR. Details can be found in Ref. 35. A comparison of TCSPC-FLIM and frequency-domain FLIM (on the development level of 2003) can be found.128,129

Frequency-domain FLIM can be achieved by modulating the detector and detecting images for different phase of the modulation. FLIM by a modulated image intensifier was introduced by Lakowicz and Berndt in 1991.130 The principle of the detector is the same as for the gated image intensifier. In fact, the same intensifier tubes are used for gated and modulated operation. The difference is only in the signal applied to the gate electrode. The general modulation and phase measurement principle is as shown for single-point-detectors. The photon efficiency depends on the waveform of the excitation and the waveform of the modulation. For pulsed excitation and sinewave modulation of the amplifier, the photon efficiency is about 0.5.35 Readout rates for the images are in the range of 100fps. Therefore, the acquisition times are in the same range as for gated image intensifiers.

Elder et al. presented a frequency-domain technique that avoids aliasing of the modulation signal with possible dynamic changes in the sample.131 The image rate obtained was 5.5fps (excitation power and pixel number not known). Clayton et al. used a modulated image intensifier for anisotropy decay imaging.132 The combination with light sheet microscopy has been described by Greger et al.111 Choi et al. used a modulated image intensifier in combination with temporal focusing.106

4. Improving Speed of Data Analysis

4.1. The task of FLIM data analysis

FLIM systems deliver data containing fluorescence decay curves, photon numbers or intensities in different time intervals, mean photon arrival times, or phase and amplitude values in the individual pixels. FLIM data analysis converts these data into color-coded images of an apparent fluorescence decay time or other parameters related to lifetime.

Fit procedures are usually used to derive the decay parameters from data that contain photon numbers in a large number of time channels in the pixels. In the simplest case, only the fluorescence lifetime of a single-exponential approximation of the decay may be determined. In most applications, however, the fluorescence decay in each pixel is described by the sum of several decay components with different lifetimes and amplitudes. In these cases, color-coded images of the lifetimes or amplitudes of the components, averages of the lifetimes of the components, or ratios of lifetimes or amplitudes are built up.

In a real FLIM system, the fluorescence is excited by laser pulses of nonzero width, and detected by a detector that has a temporal response of nonzero width. The combination of both is the IRF, i.e., the signal shape the system would record for an infinitely short fluorescence lifetime. Therefore, the detected signal waveform is the convolution integral of the fluorescence decay with the IRF, i.e.,

The of a homogeneous population of molecules in the same environment is single-exponential. In other situations, is double-exponential or triple-exponential, which is the sum of single-exponential terms characterized by the lifetimes of the exponential components with the amplitudes of the components . In principle, models with any number of exponential components can be defined. However, higher-order models become so similar in curve shape that the amplitudes and lifetimes cannot be obtained at any reasonable certainty. Therefore, FLIM analysis usually does not use model functions with more than three components. It is also worth pointing out that even in the case of only two exponential components, there exists an inherent difficulty in recovering the exact amplitudes and lifetimes because one can vary the lifetime to compensate for the amplitude or vice versa.133

The convolution integral cannot be reversed, i.e., there is no analytical expression of for a given and IRF. There is also another complication: The measured data contain noise from the statistics of the photons, i.e., itself is not accurately known. Any attempt to directly calculate from the recorded data is therefore in vain. The standard approach to solve the de-convolution problem is to use a fit procedure: A model function of the fluorescence decay function is defined, the convolution integral of the model function and the IRF is calculated, and the result is compared with the measured data. Then the parameters of the model function are varied until the best fit with the measured data is obtained.134 In FLIM data, the operation is repeated for all pixels in the image.

Normally when only a single FLIM image is recorded and analyzed, the speed of data analysis is not important. The situation is different when changes in FLIM images are to be observed online. Typical situations are in cell imaging, when cells with a special signature within a larger sample must to be found, or in clinical imaging, when suspicious tissue lesions are to be located within a large area of investigation. In these cases, FLIM data not only need to be recorded but also be processed and displayed at high rate.

There is a number of different data processing algorithms for FLIM data. The algorithms differ in photon efficiency, i.e., at which accuracy they deliver data from a given number of photons, in the amount of information they deliver from a given type of FLIM data, and in the computational effort for a given number of pixels. Processing times thus depend on the complexity of the data at the input of the algorithm and at the output of it. For example, for processing data that contain photon numbers in just two time gates per pixel into single-exponential lifetime values, the computational effort is negligible. For data containing pixel data in the form of fluorescence decay curves in a large number of time channels, the computational effort is much higher, especially when not only a simple lifetime has to be derived from the data, but also a full set of amplitudes and decay times for the components of a multi-exponential decay.

Despite the differences in the algorithms, all data analysis methods have one feature in common: No data analysis procedure can deliver lifetime data at an accuracy higher than the square root of the number of photons in the pixels. A higher accuracy may be obtained by binning the decay data or by image segmentation and combining pixels with similar decay signature. The increase in accuracy is the result of a higher photon number in the binning area.

A number of commonly used data analysis methods will be discussed in the following section.

4.2. Algorithms for FLIM data analysis

For curve fitting with minimum error, least-square (LS) algorithm is often preferred, it is very simple and convenient. However, the algorithm requires enough number of photons as data point for fitting, otherwise the fitting error is very large and it even fails to resolve the components of multi-exponential decay functions. Also, due to the complex iterative process, the algorithm sometimes may be very time-consuming when the number of pixels for lifetime calculating is too large. Moreover, fitting is typically dependent on initial conditions of the parameters, and that a true global minimum of the chi-squared surface has to be found, not just a local one. Many of the algorithms that have emerged so far are based on improving its deficiencies in FLIM data analysis.

4.2.1. Algorithm with fast calculation speed

Of all FLIM data analysis procedures, fit algorithms deliver the most complete information on the parameters of the decay curves. However, the computational effort is enormous: High quality time-domain data can consist of millions of pixels, containing hundreds of temporal data points each. A decrease in processing time is unlikely to be obtained from algorithm optimization. A promising way may, however, be parallel processing of the pixels in GPUs.

For fitting the convoluted model function to the data points, usually the Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) algorithm is used.135 The algorithm features fast convergence, good fitting stability, and reliably resolves the components of multi-exponential decay functions. For a single-exponential decay, it delivers a relative standard deviation close to the square root of , yielding a photon efficiency close to one. However, the computation time is on the order of several minutes for images of pixels and 1024 time channels.

Laguerre polynomial analysis

The Laguerre analysis algorithm presented by Jo et al. derives florescence lifetimes from two weighted moments of the decay data, with the weighting functions being two orthogonal Laguerre polynomials.136,137,138 The authors optimized the Laguerre parameters based on nonlinear LS and automatically calculated the lifetimes of different system models. The calculation time is much shorter than for fit algorithms. The authors also state that the number of temporal data points (or gated images) required for Laguerre is less than that required for deconvolution by the LM algorithm. Although a reduction in the number of data point has no influence on the acquisition time of TCSPC, it can have a large impact on the acquisition time of a gated image intensifier. In that case, the need of less temporal data points indirectly shortens the image acquisition time and increases the imaging speed.

First-moment calculation

An almost ideal SNR for lifetimes from TCSPC data can be obtained by calculating the first moment (1) of the decay data.139 The method was first suggested by Bay in 1950 for the determination of excited nuclear state lifetimes.140 The 1 of a photon distribution is

1 can be considered the average arrival time of all photons in the decay curve. The fluorescence lifetime (of a single-exponential decay approximation) is therefore the difference of the 1 of the fluorescence decay curve and the 1 of the IRF. What is important for obtaining correct 1 lifetimes is that the background of the decay signal is negligible, and that the entire decay curve is recorded. This is normally no problem for TCSPC systems.

The calculation of 1 lifetimes is very fast. Different from in Laguerre polynomial analysis, only the sum of the photon numbers weighted by the time needs to be calculated. Becker et al. have applied the 1 algorithm to TCSPC-FLIM and achieved FLIM imaging of a Convallaria sample with online lifetime display at an imaging speed of 10 fps for -pixel images.37,141 Images of pixels to pixels with 256 time channels per pixel were still calculated within less than 100ms. Zeng et al.142 have compared the 1 method with the traditional LM algorithm and shown that the 1 method can achieve higher accuracy for shorter lifetime and fewer photons; these results were verified by experimental measurements of the short lifetime of CdS nanowires. Zheng et al. introduced “mean photon arrival time” as a fast and straightforward parameter in their protocol,27 which is similar in meaning to 1 without requiring any fitting to be performed.

The moment technique can be extended to the calculation of multi-exponential decay parameters. In addition to 1, also higher moments are determined and used in the calculation. The procedure is described by Isenberg et al.139 The analog mean delay (AMD) method introduced by Won123,143 directly delivers moments of the fluorescence decay functions. The results are therefore equivalent to the 1 calculation of TCSPC data. The moments delivered by the AMD system, do, however, contain a large contribution from the low-pass filters used in the recording circuitry. This contribution is on the order of 50ns. It cancels out of the results when the lifetimes are calculated.

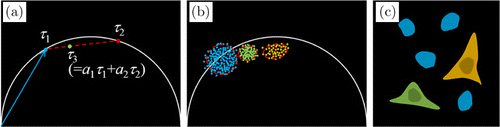

Phasor analysis

Phasor analysis has been introduced in 2008 by Gratton and Digman.144 It is based on the Fourier transformation of the decay data into the frequency domain. In the frequency domain, the decay data are expressed as amplitude and phase values at subsequent harmonics of the repetition frequency. As it turns out, a good representation of the decay signature is obtained already if only the phase and the amplitude at the fundamental repetition frequency are used. Such data describe the fluorescence decay in each pixel by just two numbers — the phase and the amplitude of the first Fourier component. It should be noted that careful calibration with a suitable reference sample is usually needed before analyzing the phasors of the experimental data.

Phase and amplitude (the “Phasors”) for the individual pixels can be displayed in a polar plot. The phase is used as the angle of the pointer, the modulation degree as the amplitude.144 Phasor analysis does not primarily aim at determining fluorescence lifetimes or decay components for the pixels. Instead, it uses the phase and the modulation degree directly to separate or identify fluorophores or fluorophore fractions, and determine concentration ratios of different fluorophore fractions.145,146 Typically, the phasors of pixels with single-exponential decay profiles are located on a semicircle with a location determined by the fluorescence lifetime. Phasors of sums of several decay components are linear combinations of the phasors of the components. Phasors of pixels with multi-exponential decay profiles therefore end inside the semicircle.

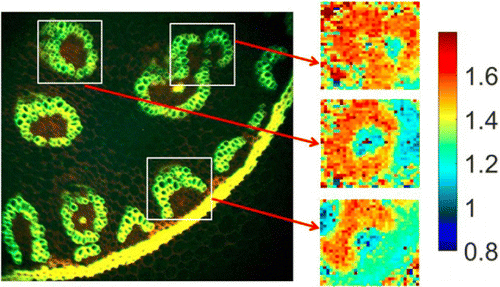

Pixels with similar amplitude-phase values form clusters in the phasor plot. Pixels with similar decay signature can thus be identified in the phasor plot, combined for further analysis, or back-annotated in the image. This automatic image segmentation function is probably the biggest advantage of phasor analysis. An example is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Illustration of phasor analysis. (a) Pixels in a phasor plot. Phasors of pixels with single-exponential decay profiles locate on a semicircle (e.g., , ; phasor of pixels with multi-exponential decay profiles locate inside the semicircle (e.g., . (b) Pixels with similar phasor form clusters in the phasor plot. (c) Lifetime image of cells with different fluorescence lifetime. Colors correspond to different phasor clusters.

The computation time for phasor analysis is very short compared with a fit procedure, similar to that for Laguerre method, but probably a bit longer than that for 1 analysis. The components of a phasor can be considered weighted moments of the photons in the decay curve, where the weighting functions are sine and cosine functions. Computation times for pixels with 256 time channels are below 1s. Due to the fast calculation, phasor analysis is basically capable of delivering images in online-FLIM applications.

However, for phasor analysis, direct conversion into color-coded lifetime images is, although generally possible, not normally considered. Applications rather focus on the ability to combine pixels of similar decay signature. Lifetime data can thus be obtained from FLIM data with very low photon numbers.2,4,144 Fereidouni et al.147 have used the phasor method to analyze multi-spectral data (image size of pixels) of seven spectral channels of two-color labeled fibroblasts in approximately 4s, with a time resolution of 200ps and an accuracy of 10% (photon count of only 108).

Rapid lifetime determination method

The rapid lifetime determination (RLD) method dates back to Woods148 in 1984 and Demas149 in 1989 who tried to reduce the computational effort of fluorescence lifetime analysis. The method uses photon numbers and intensities in two or more time windows placed on the decay curves. For a single-exponential decay, the calculation effort is reduced to summing up the photons in two time windows and calculating

Double-exponential decay profiles can be determined by using additional time windows.150 The method is fast and efficient for gated images intensifiers,95,96,105,109 gated photon-counting systems,84,85,86,87,88,89,90 and directly gated CCD sensors.100 Liu et al.151 have optimized data analysis in time-gated FLIM technology by combining the 4th-order partial differential equations of each pixel intensity with RLD to correct for the existing noise of the algorithm in the calculation process, thus enabling time-gated FLIM to quickly acquire lifetime images with high lifetime accuracy. This method is expected to be applied to live cells and rapid biomedical process imaging in the future.

A problem in conjunction with RLD is under-sampling of the signals. The fluorescence signal rises somewhere in the first time gate, and the rising edge is slowed down by the convolution of the fluorescence decay function with the system IRF. Therefore, the intensity detected in the first time gate is not correct. The data can certainly be corrected for considering the effect of the IRF, but this requires that the IRF is stable in shape and temporal position. Another way to avoid the influence of the IRF is to place the first time gate behind the IRF. However, a large part of the photons is then lost, resulting in a substantial decrease in photon efficiency. Moreover, if several decay components are to be resolved (by using additional time gates), the amplitudes of the components cannot be correctly determined.

The RLD method is very fast and reasonably efficient for data obtained by gated detection systems with a limited number of time gates. For data recorded in a large number of time channels, such as TCSPC data, it is inferior to the moment and the phasor method. Details on the accuracy and the photon efficiency of RLD can be found in Refs. 34,35 and 150.

Other fast analysis method

Li et al.152 have proposed a fast bi-exponential decay center-of-mass method (BCMM), which can obtain more accurate bi-exponential component lifetimes and ratios than nonfitting algorithms such as the phasor method and moment method, with simpler and faster analysis under low hardware requirements. They have also developed the artificial neural network (ANN) approaches for fast FLIM data analysis, which achieved 180-fold faster than conventional LS curve-fitting because of almost no requirement of iterative process and initial condition.153

Cuenca et al.154 have used look-up tables and pattern recognition (LUT&PR) techniques to identify the most suitable lifetimes and ratios from the bi-exponential decay model curves and different IRF models, thus enabling real-time FLIM data processing at a speed of at least 30kHz per pixel. The authors have performed rapid FLIM imaging (field of view of pixels, 2mm 2mm) in the oral mucosa of volunteers; the detected lifetime was consistent with those obtained by the standard LS algorithm.

4.2.2. Algorithm with low photon number

When LM algorithm is used for data analysis, problems can occur when the data contain time channels without photons. The algorithm uses an LS fit that takes into account the (absolute) standard deviation of the photon number in the individual time channels. This is done by applying a weight function of 1/(+1) to the differences between the photon numbers in the time channels and the corresponding values of the model function. The weight function works well for channels with , but it overweighs channels with lower photon numbers. The result is that the decay times can be biased towards lower decay time if the fit range includes channels with extremely low (or zero) photon numbers.155

The problem of the weight function in LM algorithm has been solved by maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) algorithm.156,157 Taking into account the Poisson distribution of the photon numbers in the time channels, the algorithm determines a probability that a given value of the model function fits to the measured data point. Optimization is based on the combined probabilities of the time channels. The algorithm works well at low photon numbers, where 1 and phasor analysis work with less computational effort.

Le Marois et al.158 have proposed a noise-corrected principal component analysis (NCPCA) based on Poisson statistics to correct the noise error in TCSPC-FLIM data acquisition, and the system is able to detect the distribution of the microenvironment at low photon count. The number of photons required to determine the unknown components is even less than that required in phasor analysis, thus increasing the execution speed. With this method, the authors have obtained a direct distribution of the cell membrane microenvironment in live HeLa cells.

In addition, the Bayes analysis (BA) proposed by Rowley et al. can be used to analyze the single-exponential and bi-exponential decay models of TCSPC data at low photon numbers, and its accuracy is even higher than those of the LS and MLE algorithms.159 CS method has also been reported to analyze FLIM data, requiring even lower photon number.160

The performance and the range of applications of different algorithms are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. A comparison of decay analysis methods can be also found in Ref. 161.

| Algorithms | LM (LS) | Laguerre polynomial | M1 | Phasor | RLD | BCMM | ANN | LUT&PR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation speed | + | + + | + + + | + + | + + + + | + + + | + + + + | + + + |

| Accuracy | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + | + | + + + | + + | + + |

| Ability to resolve multi- component | + + + | + + | + + | + + + | + | + + | To be studied | + + |

| Main feature | Need iteration, long calculation time | Rapid deconvolution | Need to know IRF, fast and simple | Nonfitting, frequency domain analysis | Fast and simple | Fast and simple, hardware friendly | High-throughput data analysis | Parameter matching with different decay model curves and IRF models |

| Algorithms | LS | MLE | BA | Phasor | M 1 | NCPCA | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate minimum photon | 1000 | 300 | 200 | 100–200∗ | 200 | ||

| Accuracy | + + | + + + | + + + | + + | + + | + + + | +++ |

| Complexity | + + | + + + | + + + | + + | + + | + + + | ++++ |

| Main feature | Simple and convenient | Noise with Poisson distribution | Available for complex IRF and multi-exponential models | Nonfitting, frequency domain analysis, require calibration | Sensitive to background noise | Noise with Poisson distribution, resolve multi-component | Multi-exponential sparse lifetime distribution analysis |

5. Summary and Outlook

The acquisition time of a FLIM technique is a complex function of many parameters. It depends on the photon rate which can safely be obtained from the sample, on the efficiency at which the technique obtains fluorescence lifetimes or decay curves from these photons, on the number of pixels of the image, on the demands for the lifetime accuracy, for the time resolution, and for the image quality. It also matters whether a technique records a full fluorescence decay curve in each pixel, a phasor, or just intensities in a few time gates after the excitation pulse. Also, the optical way of image recording is important. FLIM with scanning techniques is parallel in time but sequential in space, conventional wide-field FLIM is parallel in space but sequential in time. Since there are more pixels in space than data points in time, wide-field imaging is usually faster than scanning. However, scanning delivers image of a defined focal plane inside a sample and suppresses the influence of scattering, while wide-field imaging does not. Moreover, scanning techniques are compatible with multiphoton excitation and nondescanned detection. New techniques are attempting to retain the advantages of both. For example, wide-field TCSPC-FLIM based on SPAD array is fast because it is parallel in both space and time, while wide-field FLIM combined with optical sectioning techniques can overcome or mitigate the drawback of conventional wide-field FLIM imaging. How well a technique performs and how fast it records therefore depend on the performance requirements of the particular application. A FLIM technique which is fast and efficient for one application may be entirely inappropriate for another.

The speed at which FLIM images can be displayed depends both on the speed of the recording and the speed of the data analysis. Different ways of data analysis differ considerably not only in the computational effort but also in the type of data they process, in the amount of information they extract from the recorded data, and in the efficiency at which they obtain this information from a given number of photons. Therefore, the speed of data analysis must be seen in conjunction with the demands for the information delivered and thus with the particular FLIM application.

In recent years, FLIM technology has been developing rapidly. The acquisition speed of TCSPC FLIM has been increased by almost two orders of magnitude, fast TCSPC based on multi-stop TDCs and on parallel operation of TCSPC channels has been developed, a method for recording fast dynamic lifetime changes by triggered accumulation of images has been introduced, and multi-beam scanning in combination with SPAD-TDC arrays has been demonstrated. Analog-recording techniques in the time-domain and in the frequency-domain have been refined and demonstrated to deliver images at extremely high rate at high intensities.

Wide-field FLIM techniques, previously reigned exclusively by gated and modulated image intensifiers, have been supplemented by wide-field TCSPC, by SPAD arrays with internal TDCs, gated SPAD arrays, and gated or modulated CCD image sensors. The depth sensitivity of wide-field detection has been improved by combination with structured illumination, Nipkow-disk scanning, multi-photon multi-beam scanning, compressed imaging, and two-photon temporal focusing.

In the range of FLIM data processing, development has resulted in a number of fast methods, in particular, phasor analysis, first-moment analysis, Laguerre-polynomial analysis, and time-gated analysis. The techniques differ in the type of data they can efficiently process, and in the information they extract from the data. However, these algorithms are not likely to replace classic fit algorithms. Processing time can, and most likely will, be substantially be decreased by advanced computing technology, especially Graphics-Processor Computing.

All these developments have directly or indirectly increased the speed at which FLIM data can be recorded and displayed. Surprisingly, technology development has not yet resulted in a corresponding increase in the number of publications in biomedical applications. The reason is probably that a large part of the technology development is targeting only the recording speed instead of the complex performance requirement profile of a wide range of applications. Biomedical applications would benefit more if more parameters (wavelength, polarization, etc.) would be considered in future fast FLIM technologies.

Conflict of Interest