A comparative study on water and dry coupling in photoacoustic tomography of the finger joints

Abstract

We present a systematical study on comparison between water and dry coupling in photoacoustic tomography of the human finger joints. Compared to the direct water immersion of the finger for water coupling, the dry coupling is realized through a transparent PDMS film-based water bag, which ensures water-free contact with the skin. The results obtained suggest that the dry coupling provides image quality comparable to that by water coupling while eliminating the wrinkling of the finger joint caused by the water immersion. In addition, the dry coupling offers more stable hemodynamic images than the water coupling as the water immersion of the finger joint causes reduction in blood vessel size.

1. Introduction

Photoacoustic tomography (PAT) provides optical absorption images from the captured ultrasound signals generated from tissue thermally expanded by laser pulses.1 PAT can visualize vasculature with high contrast and high resolution, and can image synovial vascularity along with other joint tissues, which facilitate the diagnosis and monitoring of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)2,3,4 and osteoarthritis (OA).5,6,7 PAT has also been applied to vascular examination,8,9,10,11,12 the detection of breast cancer,13,14,15 thyroid cancer,16,17 oral cancer,18,19,20 studies of bone pathology21 and dermatology.22,23

The acoustic detection in PAT typically needs a coupling medium, such as water, gel, air, between the tissue surface and the ultrasound transducer24 to facilitate the transmission of ultrasound energy from the tissue to the transducer.25 It is thus far known that the water and gel present the highest transmission coefficient, the lowest reflection, and an attenuation coefficient and acoustic impedance close to that of the skin.26 While the most widely used coupling medium in ultrasound imaging is gel,27 the most widely used coupling medium in photoacoustic imaging is water.19,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37 This is because the concave detectors widely used in photoacoustic imaging require the use of a large amount of gels, which could produce bubbles to affect the acoustic impedance.38 Air as a coupling medium for PAT has limited sensitivity.39 If direct water immersion is used for acoustic coupling, it may cause some uncertain changes in physiological parameters, such as water immersion wrinkling (it refers to the phenomenon of skin wrinkles caused by human fingers immersed in water) which changes the blood flow velocity and induces vasoconstriction.40 This affects the measurement of the vascular parameters.39,41 Therefore, to resolve these issues caused by water immersion, dry acoustic coupling has been used.42 In this work, we aim to perform a systematic comparison of the dry coupling and water coupling to confirm the advantages of dry coupling as a coupling medium in PAT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Volunteers

We recruited three healthy volunteers (one female and two males) aged ≥22≥22, excluding those who took medication, had vascular cardiopulmonary disease or skin disease.

2.2. Photoacoustic tomography system

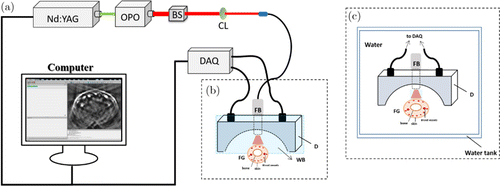

A custom-built multichannel PAT system was used in this study, as schematically shown in Fig. 1. In this system, a pulsed OPO laser system tunable from 700nm to 960nm (Surelite OPO, Continuum, CA, USA) was used for illumination with ∼4∼4ns pulse duration at 20Hz repetition rate. To compensate for the laser output fluctuations, 5% of the light energy was delivered via a beam splitter to a laser energy meter (pulsar-1, Ophir, Israel). Light was delivered to the tissue through an optic fiber bundle with line shaped illumination pattern having dimensions of 40mm (long axis) ×× 10mm (short axis). The incident fluence at 785nm was estimated to be 0.3mJ/cm2, which is below the ANSI safety limit.43 Ultrasound (US) images were acquired with a commercial system (iNSIGHT 23R, Saset Healthcare, California) equipped with a linear array transducer with 8.5MHz center frequency (SH7L38, Saset Healthcare, California) as a cross-validation for our PA findings.

Fig. 1. (a) Multichannel photoacoustic imaging system. (b) Setup of the dry coupling subsystem. (c) Setup of the water coupling subsystem. OPO: optical parametric oscillator, BS: beam splitter, CL: convex lens, FB: fiber bundle, D: detector, FG: finger, WB: water bag.

The imaging probe consisted of an optic fiber bundle and a 128-element concave ultrasound transducer array (Japan Probe Co., Ltd., Japan) where the elements were arranged in a half arc spanning 180∘ with a radius of 50mm. Each element of the ultrasound transducer is 0.95mm ×× 15mm, with a central frequency of 5MHz and a bandwidth of 4.2MHz. The imaging probe was fully enclosed with a 100μμm PDMS film which was optically and acoustically transparent. The cavity between the array and tissue was filled with deionized water for dry coupling.

A custom-built 128-channel preamplifier (60dB) was connected to the probe, and the amplified photoacoustic (PA) signals were transferred to a 64-channel analog-to-digital system (PXIe5105, NI. Inc., USA) at a sampling rate of 50 MS/s and 12-bit digital resolution after 2:1 multiplexing. One onboard computer (PXIe8840, NI. Inc., USA) worked as control panels for the PAT system and saved the PA signal data.

The PA images were reconstructed immediately after the data acquisition by an onboard back-projection reconstruction algorithm using Labview programming (NI Inc., USA) through a high performance onboard computer. Twenty Hz single-pulse-per-frame imaging was achieved using the 64-channel data collection. To minimize motion artifacts on imaging, we used a fixture coupled with a retainer to hold the hand/finger without discomfort.

The dry coupling subsystem is shown in Fig. 1(b), while the water coupling subsystem is given in Fig. 1(c). Note that the same excitation, data acquisition and image reconstruction settings were applied to both the water and dry coupling experiments.

2.3. Phantom testing

To quantify the spatial resolution and comparison of the PAT with water and dry coupling, two phantom experiments were conducted. First, two ∼20μ∼20μm-diameter carbon fibers were embedded in a tissue-mimicking background phantom with an optical absorption coefficient of 0.01mm−1−1 and a reduced scattering coefficient of 1.0mm−1−1. Second, three ∼1∼1mm-diameter ink mixture (1% AGAR powder and 0.4% ink) were embedded in a tissue-mimicking background phantom (3% AGAR powder and 2% intralipid).

2.4. Imaging protocol

Two experiments were conducted. In the first experiment, the dry coupling was used to image the finger joints, and a total of 180 images were acquired over 180s. The temperature of the water bag was maintained at 30–32∘C. In the second experiment, the water coupling was used to image the finger joints, and a total of 180 images were acquired over 180s. In a separate experiment for water coupling, to observe whether the water immersion wrinkling of finger joints will affect the image quality, the finger was immersed in water for 10min, and one image was acquired at 0min, 5min and 10min, respectively. Volunteers did not have any skin damage after the experiment.

We used both subjective and quantitative measures to evaluate the images obtained using the dry and water coupling. For the former, we subjectively and randomly observed the images to determine whether the two coupling methods provided high image quality. Subsequently, we identified a region of interest (ROI) at the same location of a blood vessel. We then calculated the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of the ROI to measure the quality of the image.42 The CNR was calculated as the peak-to-peak PA amplitude in the ROI, divided by two times the standard deviation of the background amplitude.42 In addition, the blood volume changes in the veins and arteries in the finger joints during the 180s image acquisition were calculated to measure the stability of the two coupling subsystems.

2.5. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 5.0 was used to calculate the standard deviations from the data reported in this work.

3. Results

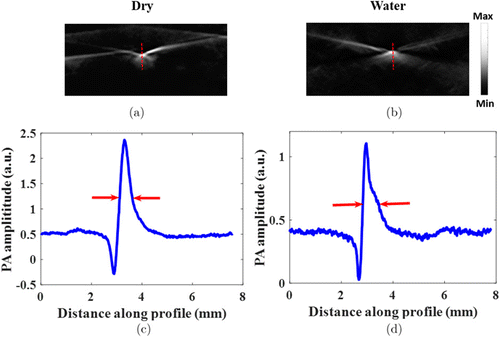

Figures 2(a) and 2(b) show that the PA images of two crossed carbon fibers with dry and water coupling, respectively. From the PAT image profile along the red dashed line in Figs. 2(a) and 2(b), the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the profile was measured to be approximately 0.30mm and 0.32mm, respectively, indicating that the spatial resolution in both cases are quite similar.

Fig. 2. Spatial resolution quantification of the PAT system. PAT image with dry coupling (a) and water coupling (b). (c) Photoacoustic image profile along the red dashed line in (a). (d) Photoacoustic image profile along the red dashed line in (b).

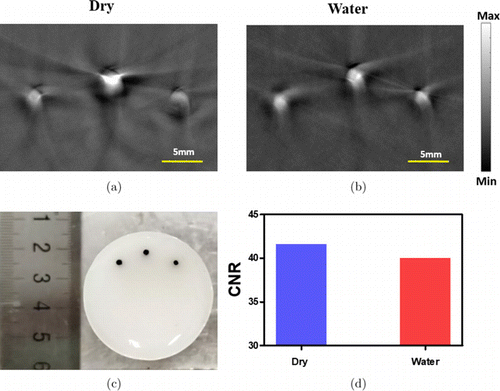

PAT images of three 1mm ink mixer objects using dry and water coupling are shown in Figs. 3(a) and 3(b), respectively. To compare the image quality, we plotted the CNRs in Fig. 3(c), and noted immediately that both dry coupling and water coupling gave very similar CNRs (41.58 versus 39.98).

Fig. 3. PAT images of three 1mm ink mixer objects with dry coupling (a) and water coupling (b). (c) The photograph of the phantom. (d) CNR of the images shown in (a) and (b).

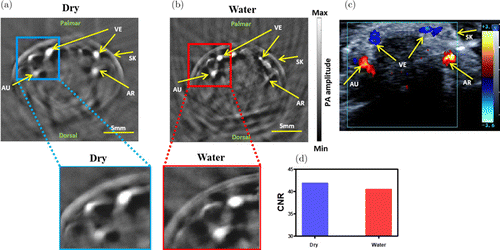

Representative PAT images of the PIP joint for a volunteer are shown in Fig. 4 using the dry coupling (Fig. 4(a)) and water coupling (Fig. 4(b)). To better compare the image quality, we plotted the CNRs in Fig. 4(d). We can see that both the water coupling and dry coupling had similar CNRs (40.51 and 41.86, respectively).

Fig. 4. Representative PAT Images of the PIP joint for a volunteer using dry coupling (a) and water coupling (b). (c) Corresponding duplex US indicates the veins of finger joint. (d) CNR calculated from (a) and (b). PIP: proximal interphalangeal joint, AU: ulnar artery, AR: radial artery, VE: veins, SK: skin.

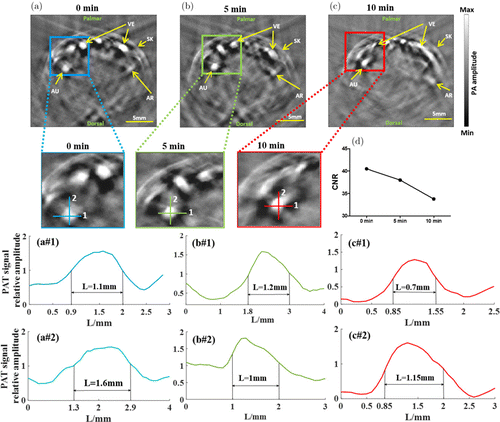

Next, we investigated whether the water immersion wrinkling produced by water coupling has an effect on image quality. Images collected by the water coupling subsystem at three time points are shown in Figs. 5(a)–5(c) with close-ups highlighting typical features of the joint images, while the CNRs at the three time points are shown in Fig. 5(d). We note that CNRs decreased over time. In Figs. 5(a1 and a2), 5(b1 and b2) and 5(c1 and c2), we plotted the PA image profiles along the cutting lines 1 and 2 show in Figs. 5(a)–5(c) where the size of the blood vessel was given by calculating the FWHM of the PA profiles.

Fig. 5. PAT images of the finger joint using water immersion at 0min (a), 5min (b) and 10min (c). (d) CNRs of the images shown in (a), (b) and (c). PA signal profiles and calculated FWHM along the cutting lines 1 and 2 for the image shown in (a) (a1 and a2), in (b) (b1 and b2) and in (c) (c1 and c2).

We see that the FWHM decreased from 1.1mm at 0min to 0.7mm at 10min in transverse direction or from 1.6mm at 0min to 1.15mm at 10min in longitudinal direction. This suggests that when the finger was immersed in the water for 10min, the lateral and longitudinal dimensions of the blood vessel were significantly smaller than that for a dry finger.

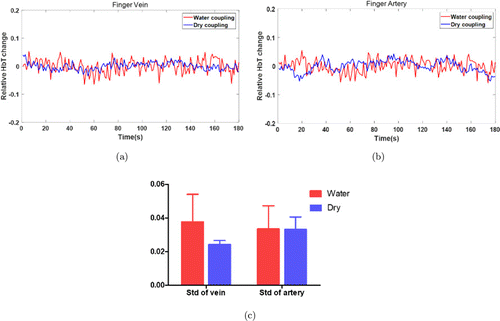

To examine the imaging stability for the dry and water couplings, relative hemoglobin (HbT) or blood volume changes over 180s averaged from the PAT images (veins and arteries) obtained from three volunteers are given in Figs. 6(a) and 6(b). The standard deviations of these blood volume changes were also calculated (Fig. 6(c)). We can see from Fig. 6(c) that the dry and water couplings show similar stability for artery, but the dry coupling offers better stability for vein.

Fig. 6. Blood volume changes over 180s for the vein (a) and artery (b) when water coupling (red) or dry coupling (blue) was used. (c) Standard deviations calculated for the blood volume change profiles shown in (a) and (b). Std: standard deviation.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

An in vivo study in healthy volunteers were conducted to assess the advantages and disadvantages of conventional water and dry coupling. We have seen that dry coupling provides image quality comparable to water coupling. In addition, we have seen that dry coupling eliminates water immersion wrinkling. However, we note that the shape of the blood vessel imaged by the dry coupling was slightly distorted. This was due to the pressure caused by the water bag to the finger during the imaging process. As the water bag was squeezed to the finger skin, the gap between the finger boundary and the surface blood vessel was narrowed, resulting in a partial oblate blood vessel. The image by the water coupling shows an undistorted, circular shaped blood vessel.

In the water immersion experiment, as the water immersion time increased, the CNRs of the images decreased. Moreover, the shape of the vein changed as the wrinkle of the finger skin increased. Visual observation of the arteries did not show significant change in shape/size. For either the veins or arteries, the size of the blood vessels became smaller as the finger immersion time increased. The main reason was that the wrinkles produced on the surface of the skin could change the blood flow velocity and induce vasoconstriction, resulting in decreased stability of blood flow changes.40

We also see that the dry coupling was more stable compared to the water coupling in terms of the changes in superficial venous blood volume. The dry coupling had similar stability in artery but better stability in vein compared to the water coupling.

We conclude from our study that dry coupling imaging of blood vessels in the finger joints provides image quality comparable to water coupling and eliminates water immersion wrinkling of the finger skin. In addition, dry coupling gives equal or better system stability than water coupling. Thus, dry coupling will be a better way especially for long-term photoacoustic monitoring of blood flow changes in the finger joints.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Natural National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (61701076).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.