Assessment of myocardial viability using a minimally invasive laser Doppler flowmetry on pig model

Abstract

The intra-operative real-time assessment of tissue viability can potentially improve therapy delivery and clinical outcome in cardiovascular therapies. Cardiac ablation therapy for the treatment of supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmia continues to be done without being able to assess if the intended lesion and lesion size have been achieved. Here, we report a method for continuous measurements of cardiac muscle microcirculation to provide an instrument for real-time ablation monitoring. We performed two acute open chest animal studies to assess the ability to perform real-time monitoring of creation and size of ablation lesion using a standard RF irrigated catheter. Radiofrequency ablation and laser Doppler were applied to different endocardial areas of alive open-chest pig. We performed two experiments at three different RF ablation energy setting and different ablation times. Perfusion signals before and after ablation were found extensively and distinctively different. By increasing the ablation energy and time, the perfusion signal was decreasing. In vivo assessing the local microcirculation during RF ablation by laser Doppler can potentially be useful to differentiate between viable and nonviable ablated beating heart in real time.

1. Introduction

Assessment of the myocardial viability is crucial for several cardiac interventions. Cardiac ablation (CA) for arrhythmias, coronary revascularization (angioplasty or coronary artery bypass graft), and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) all depend on the knowledge about presence, location and extent of viable or nonviable myocardium. CRT operations and CA assist millions of patients to recover from life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias globally. A beneficial coronary revascularization intervention requires the patient to have a substantial amount of viable myocardial tissue.1 CA creates myocardial ablation lesions to either destroy arrhythmogenic substrate or to block the arrhythmogenic reentry circuit. The formation of nonviable tissue in the lesions is vital for the effective ablation procedure. According to various research studies, the placement of the CRT device remotely from scar tissue on a heart segment with preserved viability sufficient improves the outcomes.2,3 Ypenburg et al. propose the viability and scar tissue assessment as potential selection criteria for patients eligible for CRT.4 The need to assess the viability of myocardium necessitated the adoption of various, already established, imaging techniques. The most prevalent are computed tomography (CT), contrast-enhanced computer magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), dobutamine echocardiography, radionuclide perfusion scans, and positron emission tomography (PET).5 Although these techniques provide significantly useful evidence for myocardial viability, their use is limited to preoperative and postoperative myocardial assessment; hence, they cannot be employed intraoperatively. Recently, one of the most developing areas in medicine is the introduction of optical methods for the diagnosis of biological objects in clinical practice.6,7 The physical basis of optical diagnostic methods includes various effects that occur when the interaction of electromagnetic radiation of the visible and near infrared range (NIR) with randomly inhomogeneous media with characteristic sizes of inhomogeneities is comparable to the wavelength of the probe radiation. Laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF)1,8 is a reliable noninvasive method for measuring viability of human tissue. The technique relies upon the delivery of NIR laser radiation into a segment of tissue being scattered by constituent tissue molecules. The motion of an erythrocyte within the microcirculatory system imparts a Doppler frequency shift on the photons being scattered. As a result, a range of Doppler shifts is obtained due to the orientation of microvessels in living tissue and the velocity distribution of erythrocytes. Interference of the Doppler shifted NIR laser light with light reflected from static tissue scattering produces a temporal and spatial (speckle) interference pattern. A photodetector ultimately registers the interference signal radiation, and estimates of tissue perfusion are obtained based on the frequency content of the Doppler signal. This allows for a continuous measurement of tissue perfusion based on the Doppler shifted and nonshifted photons registered by the photodetector. Due to these principles, LDF suffers from high sensitivity to motion and a reliance on arbitrary “perfusion units” (PU), limiting clinical use. However, Kaser et al. referred that LDF has an important role in clinical outcome since they are potentially valuable methods in assisting the surgeon to make the right decision in critical venous mesenteric perfusion.9 Likewise, LDF has been successfully employed for physiological research,10 cancer assessment,11,12 plastic surgery,13 transplantation surgery14 and many tissue and organ investigations.8,15,16 It follows that LDF is a potential monitoring technique for myocardial viability assessment during trans-catheter cardiac operations. The appropriate dimensioning and sizing of the laser optic probe will allow incorporating them into minimally invasive catheters in order to be used clinically for the intra-operative myocardium assessment. In this study, the use of LDF for continuous measurements of cardiac muscle microcirculation has been studied, with the purpose of providing an instrument for radiofrequency (RF) ablation monitoring. We hypothesized that laser Doppler perfusion can be used to differentiate between viable and nonviable ablated beating porcine heart in real time.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Ethical approval

This study was conducted at the Utrecht University Medical Centre (Utrecht, Netherlands). The Animal Experiment Committee of the University of Utrecht approved the experimental procedure. Two adult pigs of either sex (kg) underwent general anaesthesia. Animals were maintained and tested in accordance with the recommendations of the Guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Surgical procedure

The animals were sedated with an intramuscular injection of 25mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride and 10mg/kg of xylazine, intubated and mechanically ventilated with an oxygen/air mixture (3:2). Anaesthesia was maintained with 2.5% halothane inhalation. The electrocardiogram was recorded from three subcutaneous limb electrodes. A mid-line thoracotomy was performed to access the porcine beating heart. The pericardial sac was opened to expose the epicardium. Pulsating porcine epicardium was ablated using a standard RF irrigated catheter on different locations of the heart. The catheter was connected to a standard RF generator (Stockert EP-Shuttle, Biosense Webster, Germany). The predetermined ablation power levels were 30, 40, and 50W. Each power level was applied three times for the time intervals of 20, 40, and 60s resulting in 27 combinations of power and time. RF energy was delivered to achieve ablation lesion of 2–8mm depth. The catheter tip temperature was monitored, and the RF energy delivery ceased, if the temperature exceeded the pre-set temperature limit of 65∘C. The portion of ablated muscle was excised and submitted to histological examination.

2.3. Laser Doppler perfusion monitoring on the beating heart

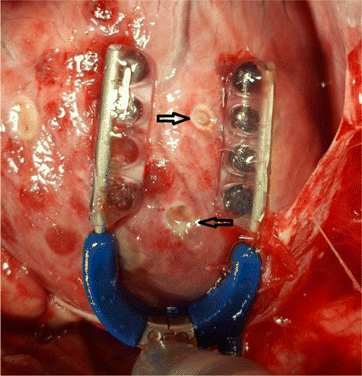

The epicardium was stabilized using an octopus tissue stabilizer (Fig. 1) during ablation and subsequent LDF measurement. The epicardial ablation lesion was clearly visibly following the RF ablation protocol. The LDF measurement fibre was orthogonally placed in the middle of the ablation lesion with no pressure. We used a diagnostic LDF system LAKK-M (LAZMA Ltd., Russia). RF ablation and LDF measurement were applied to different epicardial areas of alive open-chest pig pre and post thermal application.17 The LAKK-M LDF system is based on the laser module using a wavelength of 1064nm. The laser light was delivered, and the reflected secondary light from the tissue was collected through a multiple optical fiber probe. The probing fiber had a diameter of 6; the receiving fibre had a diameter of 400. The source-detector spacing was 1.5mm. The perfusion signal obtained was continuous over time and gave an estimate of the blood perfusion in a small sampling volume close to the fiber probe. The changes in blood perfusion per unit time in the probed volume of the tissue above 1mm3 were provided by the index of blood microcirculation () calculated according to the following equation :

Fig. 1. Experimental sample of RF epicardium ablation. Octopus tissue stabilizer (blue tool), was used to immobilize the ablation area of the beating heart. Black arrows indicate RF ablation lesions.

2.4. Data analysis and statistics

The LDF raw perfusion data were sampled at 20Hz, collected and stored digitally during the study and processed offline. The statistical programming language R 3.6.1 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing) was used for data processing and statistical analysis. LDF raw data were initially imported into R and visually inspected; LDF segments undistorted by motion artifacts were manually annotated before further processing. We next applied a bandpass filter of 0.5–2Hz to the LDF signal. The standard deviation of the pulse amplitude signal was used as a measure of pulsatility of the perfusion signal. Ablation dose was calculated at the product of ablation energy and time. Dose response analysis was performed using linear regression analysis of perfusion and ablation dose. Perfusion signals pre- and post-ablation were compared using a -test statistic. Tests were considered statistically significant at an alpha-error of .

3. Results

In order to validate the accuracy of the LDF for monitoring RF ablation and lesion formation, two porcine experiments were conducted. Eighty-four epicardial RF lesions were successfully performed in both animals. We carried out the full ablation protocol consisting of 27 measurements twice in pig once (57 lesions) and once in the second animal (27 lesions). The ablation lesions were clearly visible on the myocardium (Fig. 1).

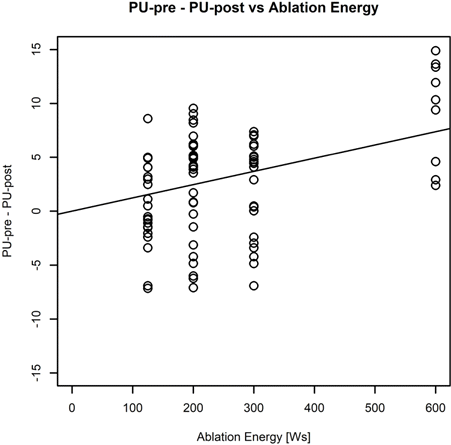

The irrigated catheter ablation temperature correlated weakly with the ablation dose (ablation duration x RF energy) as expected ) (Fig. 2). The maximum temperature did not exceed the preset temperature (65∘C) during the ablation experiments.

Fig. 2. Linear relationship between LDF signal pre- and post- ablation to RF ablation dose. For the analysis we assess the pulsatility of the signal. We used the standard deviation of the perfusion signal as measure of pulsatility.

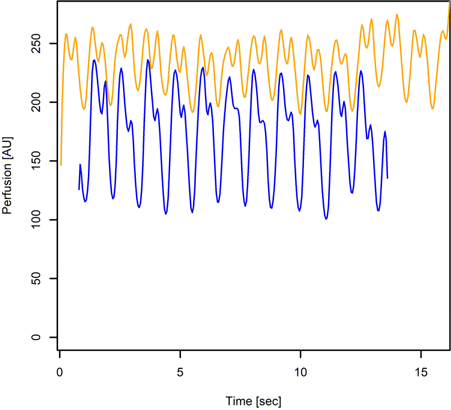

LDF was measured in all 84 ablation experiments to record the regional perfusion before and after RF ablation. The optical fiber probe was positioned over the center of the formed lesion with no pressure. Figure 3 shows an example of the registered LDF-graphs before and immediately after RF ablation. There were no complications associated with the use of the RF catheter application and LDF probe.

Fig. 3. Example of registered perfusion signal before (yellow) and after (blue) epicardium ablation.

The LDF measurements were easy to make and the computer software supplied with the LDF device allowed simple measurement of mean perfusion within the endocardium before and immediately after ablation. No significant differences were observed in local blood perfusion before ablation, whilst the signals before and after ablation were distinctively different. LDF perfusion was AU (arbitrary units) before RF ablation, and declined to AU after RF ablation. The perfusion results are presented in Table 1. A statistically significant reduction by 12% of LDF perfusion was already visible at a low RF ablation dose of 200 Ws. At maximum RF ablation dose, the LDF perfusion was significantly reduced compared to baseline (Fig. 2).

| Energy [Ws] | LDF pre-A [AU] | LDF post-A [AU] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | 22.323.02 | 21.904.04 | 0.700 |

| 200 | 23.294.70 | 20.563.27 | 0.007 |

| 300 | 24.092.45 | 21.654.75 | 0.032 |

| 600 | 22.924.49 | 13.648.25 | 0.011 |

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The physiological assessment of myocardial tissue and scar tissue can be critically important for cardiac procedures such as the surgical treatment of ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias.4,18 To meet this clinical need, several catheter-based minimally invasive methods, such as intracardiac echocardiography, optical coherence tomography and photoacoustic, are being developed.19,20,21,22,23

The laser Doppler technique presented in this paper has been evaluated in an in vivo animal model. Thermal application of the miocardium leads to changes in its optical properties and blood perfusion.24,25

LDF as a technique, due to the mechanism of its action, is able to provide a very sensitive method for non- or minimally invasive blood perfusion measurement. Using LDF intra-operatively is advantageous in several ways: it is minimally invasive and requires no administration of drugs (such as contrast agents, etc.) and the use of low-power laser light is considered to be harmless to the tissue. At the same time, it was shown when LDF is applied to the beating heart, large motion artefacts are added to the signal.26 This study uses the octopus tissue stabilizer as our tool to avoid motion artefacts in the first place (Fig. 1). As a result, Fig. 3 shows representative recordings of LDF before and after RF ablation. During ablation, with the increasing of the RF ablation dose, a significant decrease in blood perfusion and increase of the pulse-wave amplitude were observed (Table 1, Fig. 2). Even slight increases in ablation dose were associated with a decrease in both myocardial blood perfusion and pulse and circadian rhythms. Due to the difficulties in obtaining accurate and reliable results, there are rather few studies about LDF measurements on the beating heart published. As a result, there are no standard reference methods for myocardial perfusion measurements available.27,28

Despite the pronounced results presented in this study, the LDF technique requires additional adaptation to clinical use. This is primarily due to a number of limitations. In this study, we ablated the porcine epicardium; endocardial ablation poses yet another challenge due to the high concentration of erythrocytes, limiting the optical penetration depth and causing multiple Doppler shift. This leads to poor signal quality and complicates the interpretation of the data.7,29,30 A limitation of this study is in the relatively small number of analyzed ablation lesions and lack of histological analysis. Further studies should be conducted, including histological analysis. Despite these drawbacks, advances are constantly being made. Advanced signal processing techniques have been applied by several groups to overcome movement artifacts inherent to LDF so it can be used for myocardial microvascular measurements.31,32,33 In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a commercially available LDF device, which has been developed to allow continuous real-time measurement of local tissue perfusion, can be used to assess epicardial perfusion in beating porcine hearts. Our study illustrates that the LDF technique can be used to evaluate in vivo responses of the heart microcirculation to ablation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sharon Flanagan and the Utrecht University Animal Laboratory team for their assistance during animal experiments.