Differentiation of different antifungals with various mechanisms using dynamic surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning

Abstract

With the increase in mortality caused by pathogens worldwide and the subsequent serious drug resistance owing to the abuse of antibiotics, there is an urgent need to develop versatile analytical techniques to address this public issue. Vibrational spectroscopy, such as infrared (IR) or Raman spectroscopy, is a rapid, noninvasive, nondestructive, real-time, low-cost, and user-friendly technique that has recently gained considerable attention. In particular, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) can provide a highly sensitive readout for bio-detection with ultralow or even trace content. Nevertheless, extra attachment cost, nonaqueous acquisition, and low reproducibility require the conventional SERS (C-SERS) to further optimize the conditions. The emergence of dynamic SERS (D-SERS) sheds light on C-SERS because of the dispensable substrate design, superior enhancement and stability of Raman signals, and solvent protection. The powerful sensitivity enables D-SERS to perform only with a portable Raman spectrometer with moderate spatial resolution and precision. Moreover, the assistance of machine learning methods, such as principal component analysis (PCA), further broadens its research depth through data mining of the information within the spectra. Therefore, in this study, D-SERS, a portable Raman spectrometer, and PCA were used to determine the phenotypic variations of fungal cells Candida albicans (C. albicans) under the influence of different antifungals with various mechanisms, and unknown antifungals were predicted using the established PCA model. We hope that the proposed technique will become a promising candidate for finding and screening new drugs in the future.

1. Introduction

Conventional culture-based assays such as susceptibility testing, have been hardly able to meet the urgent need for diagnosis and treatment of pathogens such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses. They are inefficient and the risk of drug resistance is increased because of antibiotics abuse, albeit they are regarded as the “gold standard”.1,2,3 Therefore, developing novel and efficient analytical techniques to identify and determine the given species and then prescribe rationally accepted medications has attracted significant attention. Molecular biological techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), have been recently applied for the identification, determination, and characterization of microorganisms and antibiotic treatment.4,5,6,7,8,9,10 These methods, instead of the excessive use of antibiotics, could strengthen the understanding of microbial diversity and physiology at the protein or even gene level. However, high cost, complex operation, and vulnerability to cross-contamination impede their further development. Herein, a rapid, low-cost, user-friendly, and reliable approach for routine microbial identification, determination, and guidance for antibiotic treatment is desirable.

Over the past years, vibrational spectroscopy, such as infrared (IR) spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy, especially surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), has been extensively used for this project to utilize its advantages and offer molecular fingerprints to study the inherent biochemical composition and variations caused by external perturbations such as antibiotics, temperature, and pH.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 In particular, Raman spectroscopy is superior to IR spectroscopy in biological determination to avoid the disturbance of water. SERS could further provide a highly sensitive readout for amplifying the original normal Raman signals in determining the biological components with ultralow or even trace content. Nonetheless, some issues still exist; these include the damage of biological samples deviating from the radiation of laser upon normal dry-state acquisition, low reproducibility and reliability from the conventional SERS (C-SERS), and extra cost owing to the use of a Raman spectrometer with advanced confocal equipment to achieve high spatial resolution or precision.

The introduced dynamic SERS (D-SERS)19,20,21,22,23 has the following advantages: facile operation by the continuous acquisition of spectra without extra substrate design, superior sensitivity and reproducibility over C-SERS achieved by two important factors, i.e., forming ordered superstructure and trapping well,22 and solvent protection for avoiding damage from the laser, which has been already used in our previous study.24 In addition, considering that minimal cost and micro-automation have become significant orientations in the analytical fields, portable Raman spectrometers have gradually attracted our attention and have some potential applications in several fields such as the on-site detection of adulterated drugs and polluted wastewater.25,26,27,28,29 Therefore, versatile D-SERS, equipped with an inexpensive portable Raman spectrometer, could be very suitable for reliable and sensitive bio-detection. In this study, the above combination will be introduced to determine the phenotypic variations of fungal cells Candida albicans (C. albicans) under the influence of different antifungals with various mechanisms. Furthermore, it is worth noting that although phenotypic variations could be clarified by the interpretation of characterized signals and the corresponding changes, it is necessary to fully exploit valuable information hidden in the spectra to strengthen our understanding of biological systems and the prediction of new drugs. Machine learning methods such as principal component analysis (PCA)30,31,32,33,34,35 might be a suitable tool to achieve this goal of reducing dimensions and retaining the important information in the original spectral data, which could be comprehensively profiled by the corresponding scores and loadings. Therefore, we believe that this integrated technique, combining D-SERS with PCA, as well as a portable Raman spectrometer, would be promising to differentiate antifungals with various mechanisms and predict or screen new drugs.

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents

Silver nitrate (AgNO3) and trisodium citrate of guaranteed grade were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. And standard reference amphotericin B (AmB) was bought from the “tansoole” platform, and fluconazole (FCZ) was purchased from the National Institute for Food and Drug Control, China. In addition, echinocandins, including caspofungin (CSF) and micafungin (MCF), were purchased from Dalian Meilun Biological Technology Co., Ltd. C. albicans 451, a clinical fungus, was obtained from the Changhai Hospital.

2.2. Instruments

A Varian Cary 100 Conc spectrometer (Varian, USA) was used to record the UV–Vis absorption spectra. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were acquired using Zeiss EVO MA-10 (Carl-Zeiss, Germany). The zeta potential was measured using Zetasizer Nano ZSP (Malvern). The SERS measurements were performed with a K-sens Raman system (Ideaoptics, China) using a laser operating at 785nm with a resolution of 6cm−1. The laser beam was focused on a sample with a size of approximately 10μm using a 100× microscope objective.

2.3. Synthesis of Ag NPs

Ag nanoparticles (NPs) were elaborated according to Lee and Meisel’s method. In brief, 36mg of AgNO3 was dissolved in 200mL of H2O and heated to boil under vigorous stirring. A solution of 1% (wt./vol.) trisodium citrate (4mL) was then added, and the solution was boiled for approximately 30min.

2.4. Fungal growth inhibition assay

C. albicans was grown in Sabouraud’s agar (SDA) broth (containing 10-g/L peptone, 20-g/L agar, and 40-g/L glucose) at 30∘C with shaking for 16h. The cultures were then diluted in fresh yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) (containing 10-g/L yeast extract, 20-g/L peptone, and 20-g/L glucose) at an initial optical density (OD) at 630nm (OD630) of ∼0.1. A succession of as-prepared Ag NPs was added to the fungal cell solution to adjust the final concentration to 20, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000μg/mL to evaluate the toxicity of Ag NPs on fungal cells. Then, different antifungals including FCZ, CSF, and AmB with a concentration of MIC80 (80% of minimal inhibition concentration, which has been predetermined, and the corresponding concentrations were 64, 0.5, and 2μg/mL) were added to the fungal solution and incubated for 16h. OD630 was measured for all the samples (OD630 was determined at different incubation times of 0, 2, 4, 8, and 16h) using an enzyme-labeled instrument (MULTISKAN MK3, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.5. D-SERS measurements

A 1-mL volume of a mixed solution containing fungal cells and Ag NPs (to maintain the final concentration of Ag NPs to the above-mentioned successions of concentrations) was prepared prior to D-SERS detection. According to the corresponding fungal growth inhibition assay for Ag NPs, the optimal concentration of Ag NPs will be used for the next detection of C. albicans under different antifungal treatments. The detailed process was as follows: First, 1–3μL of the optimal mixed solution under different treatments (different antifungals at incubation times of 30, 60, 90, and 120min) was dropped onto the silica wafer, which was soaked in piranha solution [v(concentrated H2SO4):v(H2O2)=3:1] to remove the surface impurities. The collection of Raman spectra commenced immediately after sample preparation. The SER spectra were continuously (one spectrum every 5s) collected with the solvent evaporating until the intensity of the SER spectra increased to its highest (almost the 30th spectrum). After several collections, the signals decreased rapidly, and finally, no distinct characteristic feature was visible, and the tested solution became dry. All the acquisitions were performed in triplicate.

2.6. Data processing and model establishment

The acquired D-SER spectra under different conditions were pretreated with the Savitzky–Golay polynomial fitting and baseline correction, using Matlab 2016 (MathWorks, MA, USA) and Origin 2018 software. The establishment of the PCA model and prediction of new samples were carried out using the Unscrambler 10.4 software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The optimization of spectral acquisition

According to a previous work,24 the procedures for Ag NPs preparation and characterization will not be described in detail in this subsection. In short, the fungal toxicity of Ag NPs and the enhancement for pristine Raman signals using Ag NPs were investigated.

Both zeta potential trials (the same charge between Ag NPs and fungi excluded the severe toxic effect from the electrostatic interaction) and fungal assays (the growth curves of fungal cells under 20-μg/mL and even 50-μg/mL Ag NPs were close to the untreated sample) indicated that sublethal levels of the Ag NPs (20μg/mL) barely affected the nature of the tested fungal cells (Fig. S1). Therefore, the sublethal Ag NPs (20μg/mL) were selected as the optimal substrate for the subsequent spectral acquisition of fungal cells under various conditions.

Besides, the UV–Vis absorbance and SEM results revealed the good dispersity of the as-prepared Ag NPs [Figs. S2(a) and S2(b)]. As mentioned earlier, D-SERS was used in this study for the protection of fungal cells from laser radiation and superior signal enhancement to C-SERS. Hence, the sensitivity and reproducibility were investigated [Figs. S2(c)–S2(f)]. A previous study suggested that Raman intensities of fungal cells by D-SERS increased prominently compared to those by C-SERS. Moreover, 10 different batches of 107-cells/mL fungal cells were tested, and based on the evaluation of the 30th spectrum using D-SERS, the RSDs after normalization showed very low values (all below 5%). Therefore, these results indicate that highly sensitive and reproducible spectra could be achieved with D-SERS.

In summary, combining the cytotoxicity from Ag NPs and the spectral detection level, D-SERS along with sublethal Ag NPs (20μg/mL) was used for further experiments.

3.2. Phenotypic characterization of C. albicans treated with antifungals

In general, three types of antifungal candidates were prescribed to treat the infection from the opportunistic pathogen C. albicans, which include FCZ (azoles), CSF (echinocandins), and AmB (polyenes). Prior to the test of the Raman spectra, the gold standard susceptibility testing was used as a reference to determine the effect of antifungals on C. albicans. The results are presented in Fig. S3. After incubation with different antifungals for 16h, the fungal growth curve suggests that CSF and AmB exhibited relatively stronger inhibition of C. albicans than FCZ. The mechanisms reported for these three drugs also confirmed these results.36,37,38 In short, the former two (CSF and AmB), representing fungicides, significantly kill fungi, while the latter (FCZ), representing a fungal inhibitor, only restrains fungal growth. However, cultivation for 16h was too long to determine the treatment effect of these antifungals, which could retard the remedy risk of infected patients. Raman spectroscopy or even SERS, as a rapid, reliable, and sensitive method, was used to determine the treatment effect of antifungals by analyzing the phenotypic changes.

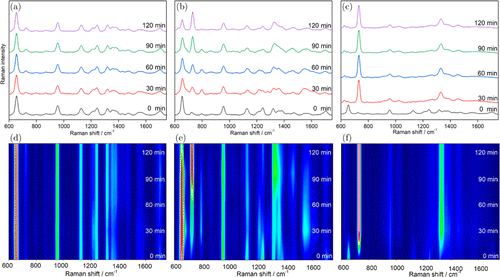

After incubation with these three drugs (FCZ, CSF, and AmB) representing azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes for different times (30, 60, 90, and 120min), the cultures were washed with ionized water and then mixed with the above optimal Ag NPs for some time. A 1–3-μL volume from the wash solutions was extracted for the acquisition of SER spectra. The resulting mean SER spectra of the untreated (without antifungals) and treated (with antifungals) samples are presented in Fig. 1. The prominent features in the pristine sample (untreated) are located at 656cm−1 (xanthine or guanine), 731cm−1(adenine or hypoxanthine), 795cm−1[O–P–O/ν(CN)], 868cm−1[ν(C–C)], 956cm−1 [ν(CN)], 1126cm−1 (lipid, amide III, or adenine), 1242cm−1(lipid, amide III, or adenine), 1325cm−1(adenine), 1382cm−1[ν(COO–)], 1465cm−1[δ(CH2)], 1573cm−1[amide II, ν(CN), or γ(NH)], and 1700cm−1(amide I). Considering the outer layer and metabolites of the fungal cells, several compounds such as amino acids, phospholipids, and nucleic acid metabolites were used to determine the origins of these signals present in the SER spectrum of C. albicans. More details are provided in the Supporting Information (Fig. S3 and Table S1). It is not difficult to find out that the 1D spectra of the cultures under the effect of FCZ scarcely changed. However, remarkable variation occurred in the species after the effect of CSF and AmB. In detail, 731cm−1 and 1325cm−1 representing adenine or hypoxanthine increased gradually but 656cm−1 representing xanthine or guanine decreased correspondingly with increasing incubation time when the cultures were treated with CSF. The possible mechanism for the change in these two peaks has already been clarified in a previous study.24 For the other changes at 1243cm−1 and 1355cm−1, the tentative assignments could be diverse and require further exploration. Interestingly, except for 731cm−1 and 1325cm−1, representing purine metabolites, clear features barely existed in the spectra under the effect of AmB. In addition, these two strong signals appeared in the earliest 30min of incubation. Therefore, the spectral variation deviating from the effect of antifungals suggests a similarity to that in the fungal growth curve (Fig. S4). However, compared to the fungal growth curve, D-SERS has more advantages, except for predicting a similar tendency. As a fingerprint technique, D-SERS provides functional group information, indicating the possible chemical components and the corresponding response upon perturbation, such as drug, light, and pH, instead of simply offering the OD value through a growth curve. This valuable information would be beneficial for further research using molecular biological methods such as transcriptomics, proteomics, or metabolomics.

Fig. 1. 1. D-SER spectra of C. albicans under different incubation times of (a) FCZ, (b) CSF, and (c) AmB at the concentration of MIC80. The 0min indicated that the concentration of Ag NPs was 20μg/mL. Panels (d)–(f) show the SERS intensity plots of the full series in a range from 600cm−1 to 1750cm−1 corresponding to the panels (a)–(c).

3.3. Evaluation of fungicides

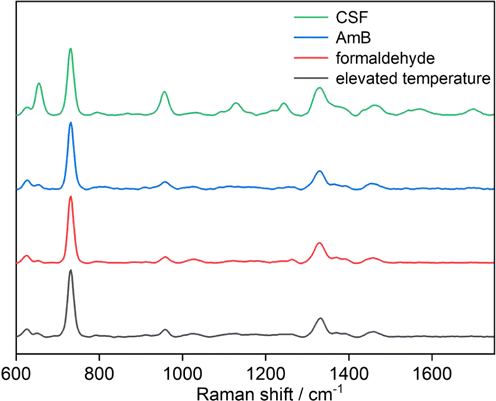

The significant enhancement of the two peaks at 731cm−1 and 1325cm−1 from the effect of CSF and AmB showed a bigger difference in the pristine culture than in FCZ. In view of the mechanisms of these two types of antifungals that cause severe damage to the fungal cells, it was hypothesized that these two strong peaks indicate the impairment or even apoptosis of C. albicans. To further confirm the physiological state of C. albicans under the pressure of the two types of fungicides, two methods of inactivation, namely elevated temperature and formaldehyde, have been used to treat C. albicans, and the results are presented in Fig. 2. It was found that similar spectral features with remarkably strong peaks at 731cm−1 and 1325cm−1 occurred and other peaks were invisible when compared with those from the above antifungals. Therefore, it was deduced that after the action of CSF and AmB, C. albicans was inactivated (death), which revealed the potential antifungal activity of these two types of antifungals. The only strong intensity of these two peaks could indicate the death of C. albicans.

Fig. 2. D-SER spectra of C. albicans under different inactivation ways including elevated temperature, formaldehyde, AmB, and CSF.

Furthermore, considering the significance of the spectral peaks, it is expected that they could be used as an indicator to screen appropriate candidates for the treatment of patients infected with C. albicans. It is clear that elevated temperatures and formaldehyde are hazardous to human cells. Polyenes antifungals, such as AmB, also have severe nephrotoxicity according to a previous report.36 It is worth noting that echinocandins, such as CSF, target the glucan synthetase and further affect the synthesis of cell walls that are absent in the human body; thus, this type would be harmless to human cells. Our previous study also demonstrated this.24

In summary, the appearance of two distinct peaks at 731cm−1 and 1325cm−1 could simply become the symbol of the fungicidal potential of polyenes and echinocandins. Only echinocandins could be simultaneously lethal to fungal cells and harmless to human cells. In other words, we deduce that spectral features that are similar to those of echinocandin-treated fungal cells could become the potential marker for finding and screening new drugs because of the theory, “structure determines nature”. However, the identification of several characteristic signals (731, 956, and 1325cm−1) in the spectra of C. albicans under the effect of echinocandins is unconvincing. Statistically, the information representing these peaks is still not enough; thus, the whole spectral information will be incorporated into the verification of the feature deviating from echinocandins-treated fungal cells.

3.4. Establishment of a PCA model

As mentioned earlier, to comprehensively profile the characterization of fungal cells affected by echinocandins, the information representing the whole spectra needed to be mined. However, each whole spectrum contains excessive variables (each variable indicates each data point), which could undoubtedly provide rich information, but also increase the workload of data collection and complexity of problem analysis. Therefore, a reasonable method is desirable to reduce the number (dimensions) of original variables and rather retain the important information contained in the original datasets. PCA could achieve this goal by reducing the dimensions. This pretreatment for high-dimensional feature data could preserve some of the most important features of high-dimensional data, remove noise and unimportant features, and improve the speed of data processing. Therefore, PCA was used in our study.

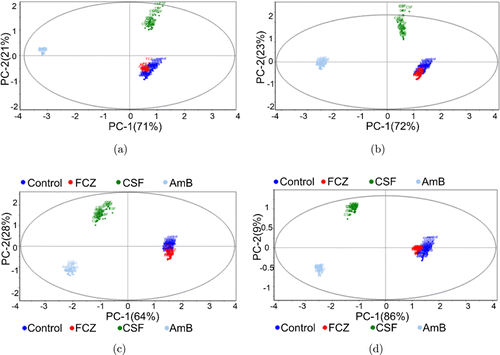

In Fig. 3, each color represents each type of sample with or without different antifungals in the PCA score plots. It was found that the scatters of each clustering gathered evenly, except for very few ones, indicating the high reproducibility attributed to D-SERS acquisition. Because of the high similarity between the spectra of C. albicans without and with FCZ, it was difficult to visually differentiate the scatters representing the spectra of these two groups (blue and red) in the score plot regardless of the incubation stage. For the samples treated with CSF (green) and AmB (gray), clear separation apart from the pristine samples appeared for the large difference from the untreated samples. Varying incubation times exhibited various classifications; the FCZ and AmB groups always remained at the extreme right and left sides, and the CSF group changed the position in the score plot, showing a time-dependent sign. When combined with 1D SER spectra, the corresponding spectra of the FCZ- and AmB-treated samples remained, and three peaks at 656, 731, and 1325cm−1 changed remarkably with an increasing time of incubation with CSF, which is consistent with that in the PCA score plot.

Fig. 3. The score plots (PC1 versus PC2) of C. albicans treated with none (control), FCZ, CSF, and AmB at different incubation times of (a) 30min, (b) 60min, (c) 90min, and (d) 120min modeled by PCA.

In addition, when referring to the loading plots for every stage, we found two special variables, 731cm−1 and 656cm−1. The variable representing 731cm−1 occupied the extreme left side in PC1 (−0.2–−0.3, Fig. S5) and the variable representing 656cm−1 occupied the extreme right side in PC1 (+0.2–+0.25, Fig. S5). When combined with the corresponding score plots, the AmB group always occupied the left-hand side, showing a relatively negative score value in PC1 (−2.1–−3, shown distinctly in Fig. S6), and the FCZ or pristine group occupied the right-hand side, showing a relatively positive score value in PC1 (+1.1–+1.5, shown distinctly in Fig. S6). Therefore, it could be suggested that the variable 731cm−1 was strongly positively correlated with AmB, and the variable 656cm−1 was strongly positively correlated with FCZ or the pristine group. These two variables showed significant influence on the PCA classification model. For the CSF group, the incubation times of 90min and 120min enabled the CSF scores to decrease below approximately −1, which is very close to that of the AmB group, which further optimized this classification model. Moreover, although the score value in PC1 at an incubation time of 90min decreased to −0.9, very close to −1.1 of the incubation time of 120min, the total PCs (PC1+PC2) (92%) of the former were lower than those (95%) of the latter. The higher total PCs could explain most of the variation in the original data more convincingly. In addition, we hope that the residual variance decreases to zero by using as few components as possible. It is worth noting that this residual variance was low down to 0.001 only when the first two components were combined (Fig. S7), and R2 calculated using the residual variance was high up to 99.9%, which revealed the excellent performance of the PCA model when the validation was used to evaluate this model. Therefore, the above result including clear classification, high total PCs, and R2, inferred that the characteristics of the sample treated with CSF as well as the other samples located in the specific position of the score plot by the first two components instead of the aforementioned only two single peaks, showed an important influence on the clustering model.

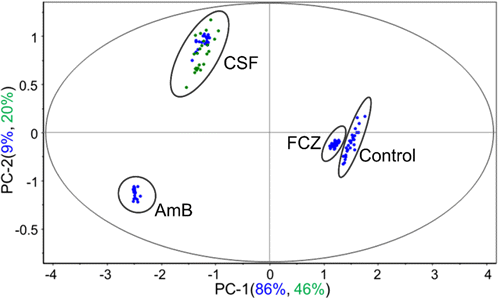

3.5. Prediction of new samples

After establishing and evaluating the PCA model, predictions for new samples need to be implemented. Micafungin (MCF) is another antifungal whose main chemical structure is similar to that of CSF. The literature has reported its potential antifungal capability, and the growth curve was also measured in our previous study, revealing one that is similar to that of CSF. In view of these similarities in the growth curve and structure, the corresponding spectra could be possibly similar. After acquiring the D-SER spectra of C. albicans cultivated with MCF within 2h, the signals highly resembled those treated with CSF, especially at the characteristic peaks at 656, 731, and 1330cm−1. However, as mentioned earlier, using only several variables representing peaks could not explain the entire spectral feature. Thus, the established PCA model was used to predict these new samples from the influence of MCF. Figure 4 shows that most of the projected samples (green) fell into the CSF groups defined by the model samples. The high total PCs (PC1+PC2) = 66% also demonstrated the high prediction by this current model. The whole spectral characteristic of the MCF group also remained close to that of the CSF group. Therefore, we deduced that the unknown antifungals with the score value within the confidence interval of the above two groups (CSF and MCF) might be regarded as potential candidates with a similar mechanism to treat patients infected with pathogenic fungi.

Fig. 4. The score plot (PC1 versus PC2) of C. albicans treated with MCF at the incubation time of 120 min predicted by PCA. The blue points indicated the calibration set of the original PCA model, and green ones indicated the predicted set.

4. Conclusion

This work introduced a powerful technique to determine and differentiate the antifungal capabilities of different antifungals with various mechanisms against C. albicans, which was verified by the “gold standard” method. D-SERS improved the sensitivity and reproducibility compared with C-SERS which has been demonstrated in our study and guarantees the reliability of further data processing. Using the machine learning method of PCA, the responses of C. albicans to different antifungals could be comprehensively profiled through the whole spectra instead of several characteristic peak signals. Herein, the model established by PCA was also used for the prediction of new candidate drugs with high accuracy. Therefore, it is expected that D-SERS combined with machine learning as well as a portable Raman spectrometer will be a promising technique to assist in the discovery and screening of new drugs more rapidly and accurately in the future.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China under the Grant Nos. 2018ZX09J18112 and 2019YFC312603 and Military Biosafety Project under the Grant No. 19SWAQ20.