ID-OCTA: OCT angiography based on inverse SNR and decorrelation features

Abstract

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) takes the flowing red blood cells (RBCs) as intrinsic contrast agents, enabling fast and three-dimensional visualization of vasculature perfusion down to capillary level, without a requirement of exogenous fluorescent injection. Various motion-contrast OCTA algorithms have been proposed to effectively extract dynamic blood flow from static tissues utilizing the different components of OCT signals (including amplitude, phase and complex) with various operations (such as differential, variance and decorrelation). Those algorithms promote the application of OCTA in both clinical diagnosis and scientific research. The purpose of this paper is to provide a systematical review of OCTA based on the inverse SNR and decorrelation features (ID-OCTA), mainly including the OCTA contrast origins, ID-OCTA imaging, quantification and applications.

1. Introduction

Optical coherence tomography (OCT), based on low-coherence interferometry, enables noninvasive and three-dimensional (3D) volumetric imaging of the anatomical microstructure in biological tissues in real-time by measuring the interference formed between the echoes from reference mirror and biological sample.1,2 With the ability to provide microscope-resolution (1–10μm) “optical biopsy”, it has evolved to become a major medical imaging technique.

Utilizing flowing red blood cells (RBCs) as intrinsic contrast agents, optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) enables fast and safe 3D visualization of vasculature perfusion down to capillary level.3,4,5,6 Because of its noninvasive, noncontact and label-free properties, OCTA has been rapidly applied in scientific research and clinical applications,7 such as ophthalmology,8,9,10,11 dermatology,12,13,14 neuroscience,15,16,17 brain imaging18,19,20,21 and oncology.22

Since the first idea of using OCTA to detect blood flow (based on Doppler principle), a large spectrum of OCTA algorithms have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and flow contrast of angiography. The purpose of this paper is to provide a comprehensive review of OCTA techniques, including the OCTA contrast origins, ID-OCTA imaging, quantification and applications.

2. OCTA Contrast Origins

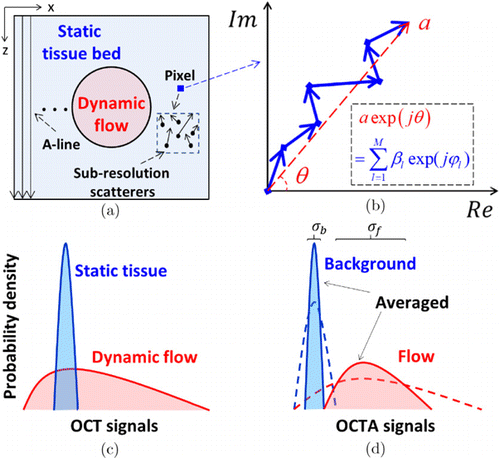

In most situations, each OCT pixel encompasses a large number of small phasors, arising from a collection of sub-resolution scatters, as shown in Fig. 1(a). The contribution of each small phasor can be expressed as a random sub-phasor βexp(jφ), where β and φ are the amplitude and phase components.23 As plotted in Fig. 1(b), the OCT signal aexp(jθ) of an individual voxel is the coherent sum of all the sub-phasors in a coherence volume with a size determined by the probe beam area and coherence length of the light source,24 i.e.,

Fig. 1. (a) Schematic of an OCT structural cross-section. Due to finite resolution, each pixel encompasses a number of sub-resolution scatters that correspond to a collection of random sub-phasors. (b) OCT signal of an individual pixel expressed as the sum of the random sub-phasors. (c) The dynamic and static resultant phasors (i.e., OCT signals) having different probability distributions. (d) In OCTA, an additional contrast algorithm is employed to quantify the magnitude of dynamic changes. The static surrounding tissues have low-magnitude values (dashed lines) and are removed by an appropriate threshold, leaving the dynamic signals to generate angiograms. Averaging further suppresses the variances of the distributions (filled areas). σb and σf are the standard deviations (SDs) of the static background and dynamic flow, respectively.23

In dynamic flow regions, the moving RBCs induce a rapid change of the spatial distribution of sub-resolution scatters, corresponding to the time-variant sub-phasors. However, in static tissue regions, the interference pattern is stationary, and consequently the sub-phasors are stable. As shown in Fig. 1(c), the probability density functions (PDFs) of the resultant OCT signals in dynamic flow regions and static tissue regions are different in the temporal dimension. Although such a statistical difference highlights the potential to differentiate dynamic signals and static signals, it requires a large amount of repeated samples to reduce the classification error, which is almost impossible in practice. Therefore, additional contrast algorithms are necessary for effectively extracting the dynamic flow information from noisy background. With an OCTA algorithm, usually, a threshold was set to remove static tissues with low-magnitude values, as shown by the dashed curves in Fig. 1(d). Besides, further averaging strategies were widely used to reduce the residual overlap, referring to the solid curves in Fig. 1(d), which will be introduced in the following section.

3. OCTA Imaging

Up to now, to accommodate various system configurations and situations, a wide spectrum of OCTA algorithms have been proposed to estimate the motion magnitude of RBCs and extract the dynamic blood flow from static tissue, which are summarized in Table 1. Generally, the OCTA algorithms distinguish dynamic flow from static tissues by analyzing the temporal changes of OCT signal between successive tomograms acquired at the same location.

| Algorithms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Research group | Signal components | Operations | Samples acquired from |

| Makita et al.27 | Phase | Differential | Temporal |

| Fingler et al.28 | Phase | Variance | Temporal |

| Mariampillai et al.29 | Amplitude/Intensity | Variance | Temporal |

| Enfield et al.30 | Amplitude/Intensity | Decorrelation | Temporal |

| Jia et al.31 | Amplitude/Intensity | Decorrelation | Temporal and Wavelength |

| Wang et al.35 | Complex | Differential | Temporal |

| Li et al.23,32,33 | Complex | Decorrelation | Temporal, Wavelength and Angular |

In terms of signal utilization, the algorithms based on phase enable high sensitivity, but they are highly susceptible to noise, especially when the local SNR is low.27,28 On the other hand, algorithms based on amplitude lose the phase information that possess highest sensitivity and the ability to detect sub-wavelength motion, thus, are difficult to realize high-sensitivity recognition of microvasculature.29,30,31 By contrast, complex-based algorithms offer high motion contrast by comprehensively using phase and amplitude information.23,32,33,34 As for signal processing, decorrelation (or correlation) operation calculates the dissimilarity (or similarity) between concessive B-scans obtained at the same location,17,30 which overcomes the shortcomings of insufficient sample size utilized in differential operations27,35 and susceptibility to motion noise in variance operation.28,29 Besides, decorrelation technique is intrinsically insensitive to the disturbance caused by the overall variation of the light source intensity36 and less sensitive to the Doppler angle.16,37

3.1. Complex decorrelation

In this paper, we focus on the complex decorrelation algorithm because of its advantages mentioned above. The local complex decorrelation D was calculated with a 4D spatio-temporal (ST) average kernel defined as

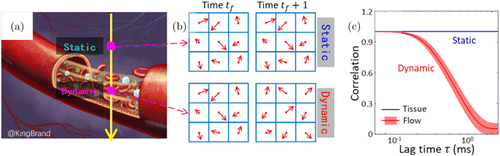

As shown in Figs. 2(a) and 2(b), the OCT signals for pixels in dynamic flow areas changed over time while the signals from static tissues remained steady. Accordingly, by calculating the correlation of OCT signals acquired at the same location between different time points, dynamic flow shows low correlation (or high decorrelation) while static tissue exhibits high correlation (or low decorrelation), and therefore can be distinguished [see Fig. 2(c)].

Fig. 2. A schematic diagram of the calculation of complex decorrelation. (a) A simplified figure of a vessel surrounded by static tissues. (b) OCT signals for pixels in dynamic flow areas and static tissues acquired from successive frames. (c) Plot of correlation versus lag time for the signals in dynamic flow areas and static tissue regions.

3.2. Relation of decorrelation to SNR

However, the computed motion index is not simply related to the motion magnitude of RBCs, but also influenced by the local signal intensity or local SNR. The SNR-dependent motion index would degrade the classification accuracy and visibility of vascular network8,11 and confuse the interpretation of hemodynamic quantification results.37,39,40 Therefore, several methods have been proposed to suppress the motion artifacts induced by random noise. The simplest method was setting an intensity threshold and removing all voxels with low SNR,30,33 but a balance must be struck between eliminating noise and including true flow in vasculature.41 To make full use of the acquired OCT data, SNR-adaptive algorithms were proposed. Makita et al. proposed a noise-immune algorithm by estimating the complex correlation coefficient of true OCT signals, rather than the measured data.42 Braaf et al. modified the complex differential variance (CDV) algorithm by normalizing the CDV signal with analytically derived upper and lower limits.43 However, those modified algorithms both involved complicated estimation of OCT parameters. Different from correcting the SNR-dependent OCTA signal, an alternative solution was to build an SNR-adaptive classifier. The initial SNR-adaptive classifiers were based on numerical analyses. Zhang and Wang distinguished the flow signal from static background in feature space by a learning method.44 Gao et al. built a classifier by fitting the relationship between reflectance and decorrelation in foveal avascular zone (FAV) with linear regression analysis.45 Li et al. solved the depth-dependent motion-based classification by performing a histogram analysis and differentiating the dynamic flow from static tissues through fitting.46 Recently, Huang et al. rigorously derived the theoretical asymptotic relation of decorrelation to inverse SNR (iSNR) and explored the distribution variance based on numerical simulation.47 In the proposed iSNR-decorrelation (ID-OCTA) algorithm, a range of 3σ was used as the distribution boundary of static signals. Accordingly, the classification line DC was defined as

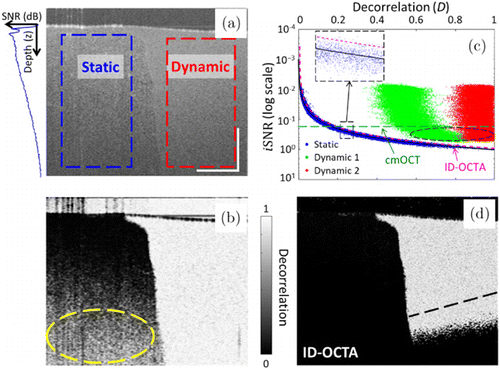

Flow phantom experiment was implemented to validate the feasibility of the proposed ID-OCTA algorithm. As shown in Fig. 3(a), the structural cross-section offers prior knowledge of the static (left half) and dynamic (right half) regions. To avoid the ambiguity on the static–dynamic boundary, only the rectangular regions marked with dashed boxes were used for further quantitative analysis. The decorrelation mapping is illustrated as Fig. 3(b). Generally, the dynamic region presents a high decorrelation value and the static region shows a low value. However, the SNR (or intensity) of the probing light decays exponentially with the increase of the penetration depth, referring to the depth profile inserted in Fig. 3(a). Accordingly, due to the influence of random noise, static regions at deep position also exhibit high decorrelation, as indicated by the yellow ellipse in Fig. 3(b). Figure 3(c) illustrates the distributions of static signals (blue points) and dynamic signals (red and green points) with different B-scan intervals in ID space with log-scaled iSNR. The static and noise signals distribute around the theoretical asymptotic ID relation [the black curve in Fig. 3(c)] and can be effectively removed by the ID classification line determined by Eq. (5) [the magenta curve in Fig. 3(c)], which demonstrate the validity of the proposed ID-OCTA algorithm. In addition, the signals in dynamic regions present higher decorrelation when calculated with a larger B-scan interval, corresponding to the conclusion in Fig. 2(c). In contrast, in the correlation mapping OCT (cmOCT), a global intensity threshold was set to remove all signals without sufficient intensity [green dashed line in Fig. 3(c)]. Therefore, ID-OCTA presents higher visibility over cmOCT in deep dynamic regions as indicated by the reserved region below the black dashed line in Fig. 3(d).

Fig. 3. Flow phantom data validate the feasibility of ID-OCTA. (a) Structural (intensity) cross-section of flow phantom. Left-half region is the static area and right-half region is the flow area. The dashed boxes indicate the parts used for ID space mapping. Inset is the averaged depth profile indicating the SNR decay. (b) Decorrelation mapping of the cross-section. (c) ID space mapping of the phantom data and the proposed classifier. The static and noise voxels are marked in blue and the dynamic voxels with different B-scan intervals are marked in red (9.9ms) and in green (3.3ms). Inset is an enlarged view of the dashed box region. The corresponding theoretical asymptotic relation is the black solid curve, the ID classifier is the magenta dashed line using Eq. (5) and the intensity threshold in cmOCT is the green dashed line. The circled area indicates flow signals excluded by cmOCT. (d) Cross-sectional angiogram by the proposed ID-OCTA, the black dashed line indicates the dynamic boundary determined by cmOCT.47

3.3. Shape feature of vessel

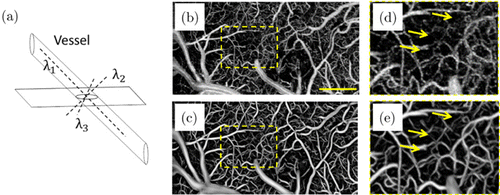

Due to limited datasets in practical cases and other inevitable disturbance factors such as breath and heartbeat, it is almost impossible to completely remove static tissues with OCTA algorithms solely.46 Therefore, traditional imaging processing methods (including median filtering, Gaussian image smoothing or some other denoising method) were widely used to enhance the flow contrast and improve vascular connectivity.48 In addition to these customary methods, many algorithms have been introduced utilizing the continuous and tubular-like patterns of vessels in 3D space [refer to Fig. 4(a)], mainly including Gabor filtering49 and Hessian-based methods.9,50,51 A widely used modified vesselness function V0(s) was defined as follows46,52,53 :

Fig. 4. Schematic of the vascular shape and performance of 3D Hessian filtering. (a) Ideal vessel shows continuous and tubular-like patterns. Enface angiograms (b) before and (c) after Hessian-based shape filtering. Panels (d) and (e) are the enlarged views of the enclosed areas in panels (b) and (c), respectively. The scale bar=400μm.46

To exploit vessels with different sizes, the vesselness measure was analyzed at different scales. The response of the shape filter will be the maximum at a scale that approximately matched the detected vessel size. Accordingly, the final vesselness estimation was defined as

Furthermore, considering the elongated tail artifacts, Li et al. proposed to calculate the second-order deviation using a 3D anisotropic Gaussian kernel with an enlarged scale in the depth direction46 :

As shown in Fig. 4(b), a number of noises appear in the initial enface angiogram. In contrast, both the flow contrast and vascular connectivity were significantly improved with 3D Hessian analysis-based shape filtering [see Fig. 4(c) and compare Fig. 4(d) with Fig. 4(e)].

Besides, some other novel-shape filter algorithms were also proposed to improve the OCTA images. Yousefi et al. compounded Hessian-filtered OCTA results and intensity images with a weighted average scheme, which mitigates the limitation of Hessian filter’s sensitivity to the scale parameters.53 Li et al. proposed another hybrid strategy: large vessel mask was generated by simply thresholding the filtered OCTA image and the microvessels were obtained by top-hat enhancement and optimally oriented flux (OOF) algorithms.54 Another recently proposed method was rotating ellipses to find the most likely local orientation of vessels and then performing median filtering with the best matching elliptical directional kernel.48

3.4. Applications

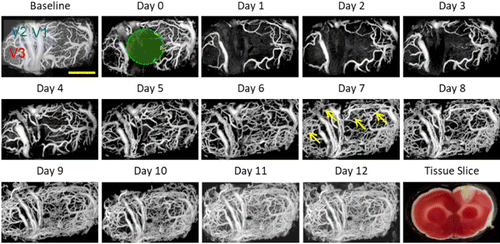

OCTA has showed its ability in brain imaging since the FD-OCT-based OCTA technique was used in a rodent cerebrovascular model.35 Recently, Yang et al. studied the spatio-temporal dynamics of blood perfusion and tissue scattering on the chronic rat photothrombotic (PT) stroke model.19,20 In the experiment, the PT occlusion model of rats was induced by the injected Rose Bengal (RB) and subsequent laser irradiation. Figure 5 presents the typical blood perfusion images in a 3.6×1.8-mm2 field of view over the chronic post-stroke time course in a male rat. In the baseline image before PT occlusion, the distal middle cerebral arteries (dMCAs), pial microvessels and the cortical capillary bed could be visualized clearly. At day 1 (1h after PT formation), all of the blood flow signal disappeared in the focal ischemic region. In the following three days, the focal ischemic region had spread significantly with obvious disappearance of the capillary network outside the irradiation core, while the large vessels in the peripheral area retained their structure with enlarged diameter. Then, from day 5, massive newly appeared blood flows could be observed both in the ischemic core and peripheral area. OCTA enables accurate assessment of the spatio-temporal dynamics of blood perfusion along the chronic recovery period, which is of great significance for understanding the pathological characteristics of these vascular diseases.

Fig. 5. Longitudinal monitoring of chronic post-PT vascular response in the male rat. Chronic monitoring was performed over 13 days. Baseline means the projection view before PT and day 1 means the day of PT administration. The green circle indicates the region of the 30-min laser irradiation. A representative tissue slice at day 1 was presented in the lower right corner. Scale bar=1mm.19

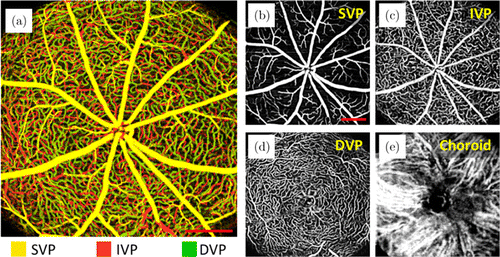

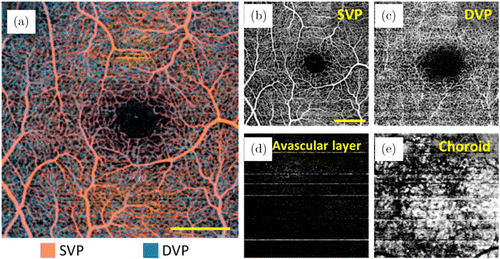

Figure 6 shows representative ID-OCTA images of mouse retina acquired with a lab-built OCT system and Fig. 7 shows the typical ID-OCTA images of human retina obtained by the prototype commercial OCTA system (Tai HS 300, Meditco, Shanghai, China).

Fig. 6. ID-OCTA of mouse retina with lab-built system. Panels (a)–(e) are the angiograms from the whole retinal layer (depth is encoded in color), superficial vascular plexus (SVP), intermediate vascular plexus (IVP), deep vascular plexus (DVP) and choroid. Scale bar=0.5mm. The lab-built FDOCT system operated at a 840-nm central wavelength and a 120-kHz A-scan rate. Here, 512 A-lines formed a B-scan, and totally 1536 B-scans were acquired in 512 y-locations with three repeated B-scans at each y-location, corresponding to a total acquisition time of 6.6 s. Scale bar=0.5mm.

Fig. 7. ID-OCTA of human retina with prototype commercial system (Tai HS 300, Meditco, Shanghai, China). Panels (a)–(e) are the angiograms from the whole retinal layer (depth is encoded in color), SVP, DVP, avascular layer and choroid. The prototype is a high-speed SDOCT system operating at a 840-nm central wavelength and a 120-kHz A-scan rate. Here, 256 A-lines formed a B-scan, and totally 1024 B-scans were acquired in 256 y-locations with four repeated B-scans at each y-location, corresponding to a total acquisition time of 2.7s. Scale bar=0.5mm.

4. OCTA Quantification

4.1. Dynamic range and uncertainty of decorrelation estimation

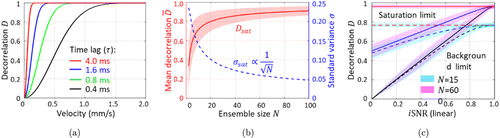

OCTA not only enables visualization of microvasculature in tissue beds in vivo, but also shows the prospect of quantitative assessment of flow parameters (including actual flow volume, velocity, flux or perfusion) as well as other indirect blood flow evaluation parameters (including vessel area density, vessel diameter index, vessel complexity index and so on).7,9 In ophthalmology, dynamical changes within the retinal and choroidal blood flow come along with various pathologies (such as glaucoma,55 age-related macular degeneration56 and diabetic retinopathy57), so the quantitative blood flow information is of great importance with regard to the diagnosis and management of ophthalmic disease.4,58 Besides, in neuroscience, neural activities highly correlate with cerebral blood flow changes, which is termed as neurovascular coupling.59 Accordingly, the hemodynamic response has been widely used to assess the brain function.60 Researches have showed that OCTA decorrelation signal closely correlates with hemodynamic parameters,39,61,62 but the limited dynamic range (including the lowest detectable flow and the fastest distinguishable flow) and the uncertainty of the decorrelation estimation hinder its further development.63 To enhance the speed range of the decorrelation estimation, variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) that calculates paired B-scans with different interscan times was proposed.64,65 As shown in Fig. 8(a), the computed decorrelation was comprehensively influenced by interscan time and flow velocity. Another widely used approach was to enlarge the average kernel, in that case, both the fastest distinguishable flow and decorrelation uncertainty were improved,66,67 as shown in Fig. 8(b). However, the kernel size was limited by the spatial resolution and the cost of imaging.

Fig. 8. The numerical simulation results. (a) Plot of decorrelation versus flow velocity. Four different interscan times (4, 1.6, 0.8 and 0.4ms) were selected and plotted in different colors. (b) Plot of the mean decorrelation (red) and standard variance (blue) versus the ensemble size (N) based on the simulation of totally dynamic signals. (c) ID space mapping of the simulated OCT voxels with different dynamic factors (black lines: totally static; blue lines: partially dynamic; and red lines: totally dynamic) and ensemble sizes (N) (cyan patch: spatial kernel with 40 times averaging, N=nxnz=15; pink patch: ST-kernel, N=nxnznfnr=600, setting nx=3,nz=5,nf=4 and nr=1).68

In addition to the spatial and temporal dimensions, the independent samples can also be acquired in the wavelength and angular dimensions at the cost of the spatial resolution.23 Jia et al. proposed to split the full OCT spectrum into several narrower bands.31 Decorrelation was computed using the spectral bands separately and then averaged. Referring to the concept of angular compounding by B-scan Doppler-shift encoding that was used for speckle reduction,69 Li et al. proposed a single-shot spatial angular-compounded OCTA method for blood flow contrast.32 In the proposed method, independent sub-angiograms were obtained by encoding incident angels in full-space B-scan modulation frequencies and splitting the modulation spectrum in the spatial frequency domain. Moreover, Li et al. demonstrated that the principles of those averaging approaches are equivalent and offer almost the same flow contrast enhancement. Accordingly, a hybrid averaging method was proposed for apportionment of the cost.23

4.2. Adaptive spatio-temporal kernel

Recently, Chen et al. proposed an adaptive ST-kernel to improve the performance of OCTA decorrelation in monitoring stimulus-evoked hemodynamic responds.68 In this study, decorrelation was computed with an ST-kernel that has two general dimensions: spatial (denoted as S, including x and z) and temporal (denoted as T, including frame tf and trial tr) dimensions :

Figure 8(c) illustrates the benefit of the ST-kernel over the traditional S-kernel. The ST-kernel increased the decorrelation saturation limit from 0.77 [cyan in Fig. 8(c)] to 0.96 [pink in Fig. 8(c)] by enlarging the ensemble size by 40 times. On the other hand, the uncertainties in both methods were similar because of the same number of samples used. However, the decorrelation calculated with ST-kernel is susceptible to the bulk motion because of the use of phasor pairs in the temporal dimension. To suppress the influence of the bulk motion, the spatio-sub-kernel was adaptively changed in the temporal dimension by solving a maximum entropy model.

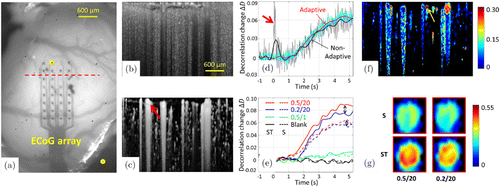

In the experiment, a transparent electrocorticographic (ECoG) was used to deliver the electrical pulses to the desired area in the somatosensory cortex [Fig. 9(a)] without obstructing the OCTA field of view [Fig. 9(b) and 9(c)]. The stimulus-evoked hemodynamic responses were presented as a decorrelation change by subtracting the mean decorrelation value of the baseline, as shown in Figs. 9(d)–9(g). Comparing the unfiltered raw curves [cyan and gray in Fig. 9(d)], the adaptive ST-kernel (cyan) effectively suppressed the abrupt motion artifacts [red arrow in Fig. 9(d)] and high-frequency fluctuations without changing the overall shape of the hemodynamic curves. In the adaptive ST-kernel, the effective suppression of the high-frequency fluctuations reduces the standard deviation of baseline (defined as the time range [−1,0]) by 57±20% and is helpful in determining the onset time.

Fig. 9. Stimulus-evoked hemodynamic responses in rat cortex in vivo. (a) Photograph of the rat cortex and a transparent electrocorticographic electrode array. The yellow dots indicate the active electrodes. The red dashed line indicates the location of the OCT B-scan. (b) Cross-sectional image (x–z) with contrast of decorrelation. (c) ID-OCTA cross-sectional image (x–z) with contrast of intensity-weighted decorrelation. (d) Time courses of the hemodynamic response to the stimulus (0.5mA/20 pulses), using different settings: nonadaptive ST-kernel without (gray) and with (black) EMD filtering; and adaptive ST-kernel without (cyan) and with (red) EMD. Hemodynamic signals were averaged over the whole B-frame [all the vessels in panel (c)]. The bold arrow indicates an abrupt motion artifact at the time t=0.3s. The adaptive ST-kernel is highly immune to the bulk motion induced by decorrelation artifacts. (e) Time courses of hemodynamic responses to different stimuli (red: 0.5mA/20 pulses, blue: 0.2mA/20 pulses, green: 0.5mA/1 pulse and black: blank) with S-kernel (dashed curves) and adaptive ST-kernel (solid curves). Averaging was performed over a single vessel [red arrow in panel (c)]. EMD filtering was performed for all curves. The double-headed arrows indicate the separability between different stimuli. The adaptive ST-kernel enables a larger dynamic range and a superior separability between different stimuli. (f) Cross-sectional mapping of the stimulus-evoked hemodynamic response (0.5mA/20 pulses, t=4.5s). The pseudo-color indicates the response magnitude and the black area is the surrounding tissue. (g) Enlarged views of the blood vessel [yellow arrow in panel (f)]. Stimulations: 0.5mA/20 pulses (left) and 0.2mA/20 pulses (right), kernels: S (top) and adaptive ST (below) and time: the average from t=4s to t=5s. Scale bar=0.6mm. Modified from Ref. 68.

Moreover, the adaptive ST-kernel had a larger dynamic range than the S-kernel and thus offered superior separability between different stimuli. In terms of the dynamic range, the decorrelation values were averaged from 0s to 5.25s for each curve and were improved by 48±13% (0.5/20), 45±12% (0.2/20) and 49±18% (0.5/1) in the adaptive ST-kernel compared with the S-kernel [see Fig. 9(e)]. As for the improvement of separability between different stimuli, the decorrelation differences between the 0.5/20 and 0.2/20 curves were separately averaged from 0 s to 5.25 s for the S- and ST-curves [see the double-headed arrows in Fig. 9(e)], and the separability was enlarged by 180±266% with the ST-kernel. A cross-sectional mapping of the stimulus-evoked hemodynamic response with high spatial and temporal resolutions can be generated [Fig. 9(f), t=4.5s]. As shown in Fig. 9(g), an enlarged view of a single vessel further demonstrated the enhanced dynamic range and improved separability between different stimuli of the proposed adaptive ST-kernel over the conventional S-kernel.

4.3. INS-fOCT

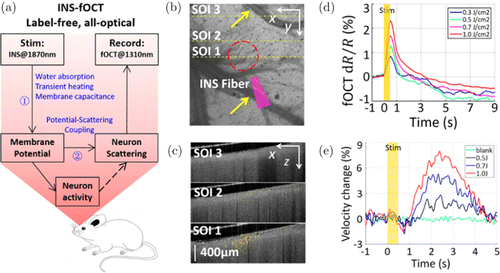

The functional optical coherence tomography (fOCT), which enables to monitor neural activity, has been used to map the functional response to visual stimulation in cat cortex70,71,72 and the response to electrical stimulation in rat cortex.73,74 However, a label-free, all-optical approach with high spatial and temporal resolutions was lacking for manipulating and mapping the brain function. Recently, Zhang et al. combined OCT and infrared neural stimulation (INS), which is a new stimulation technique for the study of cortical function,75,76 to develop a label-free, all optical approach in a contact-free, large-scale, depth-resolvable manner for stimulating and mapping the brain function in cerabral cortex up to a millimeter in depth.77 As shown in Fig. 10(a), INS induced the change of membrane potential by heating membrane capacitance. Then neuron scattering was influenced through potential-scattering coupling and recorded by fOCT. The experiment showed that INS evoked a comparably localized fOCT signal in rat cortex, as shown in Figs. 10(b) and 10(c). SOI 1 contained a maximal number of significant pixels (∼449 pixels) that spanned approximately the same lateral extent as the OISI activation; SOI 2 exhibited a reduced number of pixels (∼354 pixels); and SOI 3 exhibited no significant scattering response to INS. Figure 10(d) shows the fOCT responses at different radiant exposures. As expected, increased INS radiant exposure led to an increase in the fOCT signal magnitude.78 Figure 10(e) shows the relative blood flow velocity changes in response to INS. The onset time of velocity change was delayed by ∼1s after the INS, which is consistent with the previous studies.79,80

Fig. 10. The schematic diagram of INS-fOCT and INS-evoked spatial and temporal fOCT signals in rat cortex. (a) The schematic diagram of INS-fOCT. (b) Projection view of the 3D OCT structural image. Yellow arrows indicate pial blood vessels. Red circles indicate the site of INS stimulation. SOI means the section of interest in OCT. SOI 1: sites at the INS center; SOI 2: sites near the INS edge; and SOI 3: sites distant from the INS. The closer the sites to the INS center, the stronger the signals. The yellow dashed lines indicate SOIs 1–3 in fOCT. (c) The fOCT cross-sections (green–red color scale) superimposed with OCT anatomical image (gray scale) at a time window t=0.5s. (d) The fOCT signals for different radiant exposures. (e) The time courses of flow velocity (derived from interframe decorrelation, 240 fps) in response to the INS with radiant levels of 0 (blank), 0.5, 0.7 and 1.0J/cm2. Modified from Ref. 77.

5. Conclusion

This paper systematically reviews the OCTA algorithms, the mass sample OCTA techniques and their applications, mainly including the motion-contrast mechanism of unmarked blood flow angiography based on random phasor sum model, SNR-adaptive ID-OCTA algorithms, Hessian analysis-based shape filtering, quantitative OCTA with adaptive ST-kernel and applications. These studies are of great significance to improve the performance of OCTA and broaden its application in both scientific research and clinical application.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to National Natural Science Foundation of China (62075189), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19F050002), Zhejiang Lab (2018EB0ZX01) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2018FZA5003).