Transmissive multifocal laser speckle contrast imaging through thick tissue

Abstract

Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) is a powerful tool for monitoring blood flow changes in tissue or vessels in vivo, but its applications are limited by shallow penetration depth under reflective imaging configuration. The traditional LSCI setup has been used in transmissive imaging for depth extension up to 2lt2lt–3lt3lt (ltlt is the transport mean free path), but the blood flow estimation is biased due to the depth uncertainty in large depth of field (DOF) images. In this study, we propose a transmissive multifocal LSCI for depth-resolved blood flow in thick tissue, further extending the transmissive LSCI for tissue thickness up to 12lt12lt. The limited-DOF imaging system is applied to the multifocal acquisition, and the depth of the vessel is estimated using a robust visibility parameter VrVr in the coherent domain. The accuracy and linearity of depth estimation are tested by Monte Carlo simulations. Based on the proposed method, the model of contrast analysis resolving the depth information is established and verified in a phantom experiment. We demonstrated its effectiveness in acquiring depth-resolved vessel structures and flow dynamics in in vivo imaging of chick embryos.

1. Introduction

Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) is a wide-field high-resolution optical imaging technique with simple implementation to measure blood flow changes in vivo.1,2,3 Based on the speckle patterns derived from random interference of scattered coherent light, the local dynamics of the moving scatters (e.g., red blood cells) can be quantified by a speckle contrast K to decorrelation time τcτc model with prior knowledge of scattering regime and velocity distribution.4 The conventional LSCI works under a backscattering configuration, which is suitable for monitoring blood flow and perfusion in superficial tissues such as skin, retina and cerebral cortex. It is shown by Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) that most detected signals come from the top 700μμm brain-like tissue with a near infrared illumination.5 The depth is suitable for imaging pial vessels with a cranial window in rat, however, deeper vessels in a 2D speckle contrast image can lead to ambiguity in interpreting blood flow velocity,6 because depth itself contributes to correlation loss and thus the decrease in speckle contrast value. To acquire dynamic intravascular signals from deeper tissue, researchers developed a transmissive-detected LSCI (TR-LSCI) setup with one-way forward-scattering geometry. Li et al. systematically evaluated the performance of TR-LSCI and found that it achieved a much stronger signal-to-background ratio in thick tissue than conventional LSCI.7 The vessel depth in transmissive LSCI, however, is still not yet well resolved. The depth information is also critical for correcting the calculated blood flow.

Multifocal imaging is a fast and easy-to-implement 3D imaging method to obtain depth information.8 For imaging systems with limited depth of field (DOF), out-of-focus structures are blurred by the point spread function (PSF), resulting in widened boundaries and overestimated intensities of absorbing objects. This dependency is used in the “depth-from-defocus” (DFD) method to infer the depth of an object relative to the focal plane based on image properties such as sharpness and intensity. In LSCI, the dynamic fraction ρρ of the time-averaged intensity can be used as a DFD cue since it behaves similarly as the incoherent intensity.9 On the other hand, when the imaging depth exceeds the system’s DOF, either due to the imaging depth extension with a transmissive setup, or the decrease of DOF by a microscopic imaging system,10 the defocus effect should be taken into account to minimize the error in estimation of speckle contrast. Several groups have proposed methods to improve focusing in LSCI, for example, Ringuette combined kurtosis and cross-variance to enable the localization of best focus in an autofocus system,11 Zheng measured the system PSF and then implemented a deconvolution method to correct the out-of-focus blur and retrieve the vessel depth,9 Du used a line-scanning confocal imaging setup and realized microscopic depth sectioning.12 However, these methods have only been applied to reflective systems with imaging depth less than 500μμm. DFD methods so far haven’t yet been validated for transmissive thick tissue imaging when both intensity and correlation attenuation from multiple scattering are to play an important role.

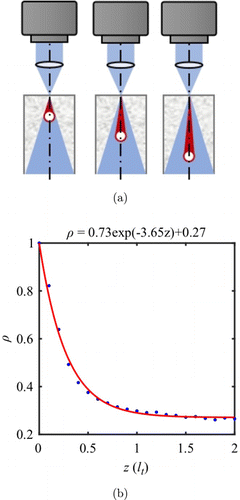

A simplified laser speckle contrast model estimates the blood flow index as 1/K21/K2, which is widely adopted in conventional real-time LSCI applications for its numerical simplicity. However, this estimation relies on several assumptions that may not be satisfied in practical situations,13 in particular, the absence of static scattering. Since visible but deep vessels usually have larger diameters, depth-dependent static scattering thus should be taken into account to avoid underestimating the intravascular flow velocities. A rigorous model between the speckle contrast and the decorrelation time was proposed in multi-exposure laser speckle imaging (MESI),14 by introducing the dynamic scattering fraction ρρ into the intensity autocorrelation function g2(τ)g2(τ). MESI uses multi-exposure speckle contrast images to fit all the parameters and thus obtain more robust flow measurement in the presence of static scattering. In transmissive multifocal LSCI, the dynamic scattering fraction of the target vessel can be retrieved in an easier way. We demonstrate ρρ decays exponentially with depth in the transmissive imaging setup with MCS.15 With an assumption of multiple scattering regime and ordered motion of blood cells, the speckle contrast can then be modeled as a function of decorrelation time τcτc and depth.16 Based on the depth information retrieved from multifocal images, unbiased blood flow index can be directly calculated from the in-focus speckle contrast image.

In this study, we propose a transmissive multifocal LSCI method to reconstruct 3D blood flow images in thick tissue. The multifocal laser speckle images are first analyzed along the vessel centerline to determine the vessel depth based on the DFD method. The depth map together with in-focus speckle contrast is then fitted with the transmissive speckle contrast model to get the blood flow in the form of the inverse decorrelation time 1/τc1/τc. Our method enables the extension of transmissive LSCI for tissue thickness up to 12lt12lt by correctly resolving the blood flow in the last 2lt2lt. We tested the reliability and consistency of our method using electric field Monte Carlo and a phantom experiment, and demonstrated the effectiveness of transmissive 3D blood flow imaging in a chick embryo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transmissive laser speckle imaging

Traditional LSCI works in the reflective imaging geometry using a large DOF lens. For incoherent imaging in natural scenes, DOF (LFLF) is a manufacturing parameter of the lens system and determines the depth of perfect imaging LD=LFLD=LF. For coherent imaging of the random medium, e.g., LSCI, LDLD is further limited by the transport mean free path ltlt (i.e., LD≈1ltLD≈1lt), within which the blood flow and vasculature can be well-estimated by analyzing the speckle patterns. The transport mean free path ltlt is dependent on the tissue’s absorption coefficient (μaμa) and reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s) in a relation of lt=1/(μa+μ′s). Thus, traditional LSCI has LD≈750μm<LF when working with 780–850nm coherent light.5

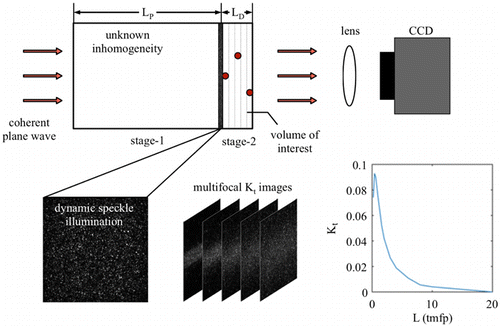

Traditional LSCI utilizes a backscattering configuration; therefore, the round trip of backscattered light significantly limits LD. Transmissive imaging geometry9 is a straightforward way to extend LD≈2lt by switching to one-way propagation. This improvement succeeds in the tissue thickness of L≤2lt−3lt.7 For thicker tissue (L≈4lt−12lt), the transmitted laser light produces speckle patterns which can be modeled as the diffusion (static) part and dynamic part. In this regime, coherent light propagation can be approximated as a two-stage procedure (Fig. 1): (1) coherent light propagates from the incident surface to the deepest imaging plane (LP≤10lt); (2) the generated dynamically speckled light field illuminates the tissue volume within the imaging depth (LD=2lt). Traditional LSCI failed in blood flow estimation due to the randomly distributed light field and depth uncertainty of vessels.17 The use of a large DOF lens further introduces significant out-of-focus blur. In this study, we propose a multifocal strategy to estimate the vessel depth and achieve blood flow imaging up to the thickness LD≈2lt from the exit plane of the thick tissue (L≈4lt−12lt).

Fig. 1. Working principle of transmissive multifocal LSCI through thick tissue.

In stage-1, phase coherence among different propagating paths produces a speckle phenomenon when coherent light transmits through the random medium. In a homogeneous and purely scattering random medium, an LP≈ls propagation produces the fully developed speckle pattern. A thicker random medium (LP>ls) degenerates the speckle patterns due to the diffusion in the intensity domain. The speckles I(t) on the LP plane are thus hybrid of diffusion and fully developed speckles, i.e., I(t)=Id(t)+Is(t). After sufficient propagation, i.e., LP≫lt, the coherent light eventually loses its phase coherence, and the speckles disappear.

LSCI utilizes the contrast (K) parameter of speckle pattern as a proxy of the blood flow velocity. Successful detection of blood flow requires K>2/SNR after L=LP+LD propagation. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of modern CCD/CMOS system is usually more than 30dB, i.e., SNR = 1000, or K>0.002, which determines the upper limit of L. Another factor affecting L is the method for calculating the contrast K. Traditional LSCI utilizes either a spatial or temporal window, i.e., Ks or Kt, to estimate the blood flow velocity. The Ks parameter could be further biased by the structural inhomogeneity after more transmissive propagation (L>4lt). Therefore, the temporal contrast Kt is more desirable for blood flow imaging. The upper bound of thickness L is estimated based on MCS. Figure 1 shows that Kt degenerates with the increase in L, assuming that a coherent and linearly polarized plane wave illuminates the left surface of the random medium. Ideally, the criterion Kt>0.002 leads the L up to 15lt. In practice, the nonideal coherent of light source18 and aberrations in the lens system limits the L. Thus, L<12lt should be the upper bound considered in this study.

In stage-2, the tissue volume (depth: LD) is illuminated by the dynamic speckle I(t) on the LP plane. Then, the transmitted speckle patterns It(t) are captured by a focus imaging system. The dynamic speckle illuminations on the LP plane introduce additional difficulties in explaining of the contrast value calculated from It(t). In order to estimate the blood flow more accurately, we need to include the depth information in the explanatory variables. Traditional LSCI, however, uses an imaging system with LF>LD, which aggregates the information in all depths. In this study, we use a limited DOF LF<LD imaging system and perform multifocus detection (MFD) that can resolve the depth information.

2.2. Depth reconstruction from Vr

After stage-1, the multiple scattering forms dynamic speckle illumination following the Gaussian statistics.19 The corresponding spatial frequency in speckle is band-limited in a Gaussian shape. In stage-2, the speckle pattern is determined by both speckle illumination and tissue scattering. The flowing motion inside the vessel blurs the speckle pattern, i.e., widening the spatial frequency range due to spatial averaging. Meanwhile, the speckle in the surrounding tissue persists. Therefore, the change in speckle spatial frequency across the vessel boundary can be used for in-focus determination in coherent domain imaging. In practice, it is difficult to measure the modulation transfer function (MTF) and precisely quantify the spatial frequency. For the classical interference phenomenon, the visibility of interference fringes, i.e., V=(Imax−Imin)/(Imax+Imin), is used as a characteristic parameter. For dynamic speckles, based on Gaussian statistics, we proposed a robust visibility parameter Vr (Eq. (1)) as the estimation of the average spatial frequency changes across the vessel :

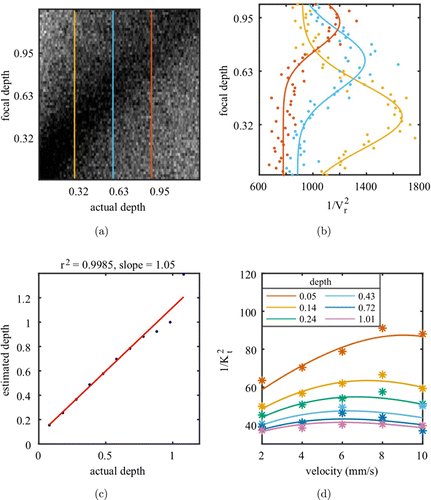

In stage-2, we use the electric-field MCS program to generate speckle images with vessels at different depths. The generated monochromatic speckle pattern then illuminates the phantom with overall LD=2.5lt. The simulated tube (caliber 0.28 lt) is positioned from the output surface down to 1.27 lt in depth. MFD is simulated by applying PSF with a 2D normal distribution. The PSF full width at half maximum (FWHM) increases with the out-of-focus depth when the focal plane is scanned along the z-direction. Figure 2(a) shows the calculated Vr(z,z0) topographies obtained from MCS. Each column in Fig. 2(a) shows the Vr parameter at the same area (tube located at z0) but different focal plane depths z. It is clear that Vr of the same tube area reaches the minimum when the focal plane is at the actual depth.

Fig. 2. (a) Vr(z,z0) topography calculated from MCS with an inclined tube phantom. Each column represents the Vr parameter at the same tube area but by applying different focal plane depths z. (b) 1/Vr(z)2 along with focal depth (z) at 3 tube depths (i.e., z0=0.32lt (yellow), 0.63lt (blue), and 0.95lt (red)). (c) Linear regression between the estimated depth (focal position with maximum 1/Vr(z)2) and actual depth (z0). (d) Fitted 1/K2t for different velocities along the inclined tube phantom using the nonlinear least squares method (R2=0.91). The depths (0.05lt to 1.01lt) are color coded.

To facilitate the depth estimation, we calculate the 1/Vr(z)2 instead in the vessel area (located at depth z0) from MFD (focal plane at depth z). Figure 2(b) shows the 1/Vr(z)2 for the tube at three different depths by scanning the focal plane depth z. The Gaussian fitting reveals that 1/Vr(z)2 always reaches the maximum at z=z0 and degrades with the out-of-focus distance z−z0. Figure 2(c) shows that the focal position with maximum 1/Vr(z)2 provides a linear and robust estimation for the actual depth.

2.3. Flow velocity mapping based on speckle contrast and depth

For the tube area in the captured speckle images, 1/Vr(z)2 is calculated and thus used to estimate the tube depth. After obtaining the depth information, the in-focus speckle contrast images of vessels are used to estimate the relative flow velocity v.

The speckle contrast can be related to the intensity autocorrelation function g2(τ) as follows :

When static scattering can’t be negligible, the intensity autocorrelation function should include the dynamic scattering fraction ρ :

Fig. 3. (a) Monte Carlo configuration with cylinder dynamic sources at different depths. (b) Exponential relationship between dynamic fraction ρ and depth z.

With a simplification of x=T/τc, Eq. (5) can be further presented as depth-dependent speckle contrast-inverse decorrelation time model:

3. Experiments

3.1. In vitro phantom experiment

The phantom medium (0.47% solidified Intralipid gel) was prepared with scattering properties μ′s=0.48mm−1 (i.e., lt=2.1mm). Intralipid emulsion with the same μ′s was injected through the embedded PE tube (PE-50, outer diameter: 0.97mm; inner diameter: 0.58mm) at a depth of 0–4.76 lt. The original focal plane was set to the top surface of the phantom. By moving the phantom up to 5mm in a step of 0.5mm, we are able to tune the focal plane down to a depth of 2.38 lt within the phantom. The flow velocity within the PE tube was controlled at 0–10mm/s with a programmable syringe pump.

3.2. In vivo experiment

Fertilized chicken eggs were obtained from a local farmers’ market and incubated at 60% humidity and 37.8∘C at a rotation rate of 360∘/2h. On embryonic Day 3, we punctured a small hole on the wide end of the egg, where the air sac was located, using the tip of pointed scissors. A round window was then prepared for imaging by carefully removing shell fragments and membranes around the hole. Another small hole for inserting the fiber was made approximately 2mm below the window with an intact membrane. The fiber was fixed by dental cement and connected to a 785nm fiber laser. The egg was placed on a sample holder for imaging.

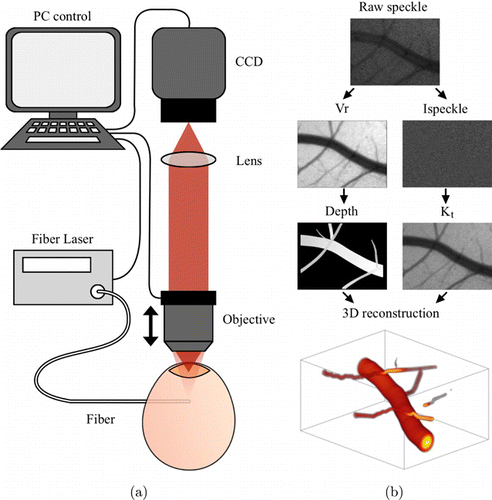

The transmissive multifocal LSCI setup is shown in Fig. 4(a). A 785nm diode laser (model: S1FC785, Thorlabs) was coupled into the single-mode fiber to illuminate the volume of interest. Speckle patterns were formed by random interference of scattered light through the sample and collected by the imaging lens coupled to the CCD camera (model: scA640-70fm, Basler). Multifocal imaging was achieved by adjusting the relative axial position of the sample from the lens. Multifocal images were taken at a focal step of 200μm below the surface for a depth range of 2mm at a magnification of 3×. On each focal plane, a sequence of 100 raw speckle images were recorded under a 5ms exposure time and 50fps frame rate.

Fig. 4. (a) Schematic of in vivo imaging experiment. (b) Data processing pipelines.

4. Results

We first validate the depth estimation strategy and the depth-dependent contrast to velocity model by an in vitro phantom experiment. The relationship between 1/K2 and the actual velocities is shown in Fig. 2(d). The data are fitted to Eq. (8) very well using the nonlinear least-squares method (adjusted R2=0.91). The superficial structures demonstrate a larger dynamic range with better linearity between 1/K2 and velocity v. In transmissive imaging, the relation between 1/K2 and velocity v demonstrates a “banana shape” (Fig. 2(d)). The decrease tendency at higher velocity results in underestimated flow when using the conventional contrast model. Our new model, however, fits well with the 1/K2 at different depths and velocities by compensating for the lower dynamic fraction in deeper structure.

Next, we further test the method in an in vivo chicken embryo experiment as one of the possible application scenarios for transmissive imaging. Chicken embryos have been widely used as a model in cardiac development for their convenience in investigating hemodynamics and angiogenesis. On each focal plane, raw speckle images are first used to calculate Vr(z). Masks for different vessels are manually segmented across all focal planes. Vessel centerlines are extracted, and the Euclidean distance transform of the inverse mask is calculated to identify the vessel radius. The 1/Vr(z)2 parameters of each centerline point in different focal planes are compared, and the maximum value indicates the vessel depth. Speckle images are then processed by temporal laser speckle contrast analysis to obtain Kt. The relative blood flow (rBF) is then calculated as v∝x=T/τc based on the model Kt(v,zd) in Eq. (8). By assuming a laminar and parabolic flow profile crossing the vessel, we are able to resolve the velocity profile and remap it to the 3D vascular structures.

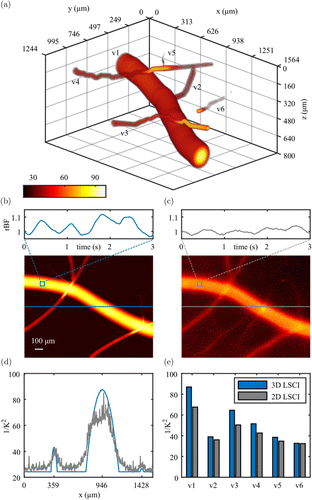

The reconstructed 3D vessel structure and flow distribution are shown in Fig. 5(a) (also see the supplementary video). The vessel branches, e.g., v2 from v1, v4 from v3, are clearly identified. The spatial relation between v1 and v6 can also be demonstrated when the traditional LSCI fails. Figure 5(b) shows the maximum projection image of reconstructed blood flow, which significantly improves the imaging SNR compared to that of raw multifocal 1/K2t stacks (Fig. 5(c)). The heart-beating-induced20 mean rBF changes in the 3D reconstruction (Fig. 5(b)) were clearly retrieved in comparison to that by traditional 2D LSCI method (Fig. 5(c)). The blood flow profiles are well-described by our reconstruction shown in Fig. 5(d). Furthermore, we evaluated the rBF index in six selected vessel segments (Fig. 5(e)), showing consistent underestimation by the traditional 2D LSCI method (gray) compared with our 3D reconstruction (blue), especially in deeper structures (v1, v6).

Fig. 5. 3D reconstruction of vasculature and blood flow in a chick embryo (a). Based on the reconstructed 3D blood flow and the raw multifocal 1/K2 images, the maximum projection images of a 1.56mm×1.24mm field of view and the mean relative blood flow fluctuations within a 50μm×50μm ROI are shown in (b) and (c), respectively, exhibiting a heartbeat signal at approximately 80bpm. Flow profiles along a horizontal line in (b) and (c) are compared in (d). The rBF indices in six vessel segments (v1–v6) are also shown in (e).

5. Discussion

In this study, we reconstructed 3D vasculature and blood flow in thick embryonic tissue using transmissive multifocal LSCI. The proposed strategy can be applied to mice or even human tissue for in vivo imaging. However, laser delivery needs accordingly be optimized to satisfy the safety in clinical applications. The effective depth of 3D imaging LD is limited by the optical properties of the tissue, (i.e., μa and μ′s), determined by both tissue properties and illumination wavelength. Usually, longer wavelengths in the near-infrared range (i.e., NIR-I or NIR-II) have larger lt and can obtain deeper reconstruction. The detection SNR is one of the factors in extending the overall thickness L; thus, scientific cameras, e.g., sCMOS cameras or single photon counting camera,21 can be utilized. The transmissive multifocal LSCI method utilizes 1/Vr(z)2 as the depth estimator derived from the interference nature of speckle. A more robust parameter or strategy should be developed to increase the precision of depth estimation for coherent domain imaging. The temporal coherence of the light source is also critical for resolving the depth information. Wider line-width or instability in laser source would fail to detect the speckle pattern after more than 10 lt propagation.

Our method retrieves blood flow information in 3D volumes, compensating for the underestimation in deeper structures. However, in transmissive optical imaging, it is difficult to distinguish dynamic scattering with mixed depths at the same lateral location; that is, if there are overlapping vascular structures, the reconstructed local blood flow will be overestimated in both vessels. Introducing multiple illumination detection angles may help to separate dynamic information from different sources. For imaging thick biological tissue, the relationship between DFD features and object depth z is also affected by intensity attenuation due to absorption, which needs further correction.22

Compared to other 3D blood flow imaging methods, such as optical coherence tomography angiography23 and speckle contrast optical tomography,24 our method preserves wide-field imaging and saves line scan time. The focal scanning time can be further saved by applying a multifocal adapter8,9 to image all focal planes in a single shot, which should improve the time resolution of this method to a level of traditional speckle imaging. Applying the state-of-art auto-segmentation method,25 real-time 3D imaging can be realized with a relatively simple configuration.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, we proposed a transmissive multifocal LSCI method for thick tissue (>4lt). Both depth information and corrected blood flow are obtained within the 2lt depth beneath the imaging surface. The theoretical framework is validated by both MCS and in vitro phantom experiments. In vivo imaging of chick embryos was also demonstrated, showing their potential in other biomedical applications.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC No. 61876108) and the National Key Research & Development Program of Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (Grant Nos. 2018YFC2002300, 2018YFC2002303).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.