The Evaluation and Obstacle Identification of Urban Infrastructure Resilience in China

Abstract

Urban infrastructure is the lifeline and material foundation for the normal operation of cities. It is of great significance to accurately evaluate the resilience level of urban infrastructure and identify the main obstacle factors for the construction of resilient cities. This paper establishes an index system for urban infrastructure resilience evaluation from three dimensions: Pre-disaster prevention capacity, disaster resistance capacity, and post-disaster recovery capacity. It also uses the CRITIC method to determine the index weights and identifies the main obstacle factors based on the obstacle degree model (ODM). The results show that urban infrastructure resilience in China is generally low and varies greatly in terms of structure across provinces and municipalities. The main obstacle factors affecting urban infrastructure resilience include the capacities to conduct pre-disaster prevention and post-disaster recovery in the production and supply of electricity, gas and water, to construct infrastructure recovery projects, and to ensure energy supply and power supply. It is recommended to promote the application of the concept of “resilience” throughout the entire process of urban planning, construction and governance, understand the current situation of urban infrastructure, coordinate the investment of resources such as funding, manpower and technology, enhance the robustness and redundancy of urban infrastructure systems, actively optimize the layout of urban infrastructure, and continuously improve the application of intelligent technologies in infrastructure systems.

1. Introduction

Cities have become the main places where human beings live together. By the end of 2022, China’s urban permanent resident population had reached 920.71 million, representing an urbanization rate of 65.2% (NBS, 2023). Infrastructures, such as water, electricity, gas and transport services, are the material foundation for the secure operation and sustainable development of cities, but they are highly vulnerable to various emergencies such as meteorological disasters. Against the backdrop of global climate change, various natural disasters and emergencies such as earthquakes, heavy rainfall and typhoons have become major obstacles to urban security and the sustainable development of cities, such as the 2011 Great E. Japan earthquake and tsunami, the 2012 Hurricane Sandy in the United States, the heavy rainstorm in Beijing on July 21, 2012, the 2015 explosion accident in Tianjin’s Binhai New Area, and the heavy rainstorm in Zhengzhou City on July 20, 2021. These disasters and emergencies not only cause significant losses to people’s lives and properties, but also have a huge impact on urban security and sustainable development. Urban resilience involves various aspects including ecosystems, society, infrastructure, economy, and even organizational systems. Due to the high complexity of urban systems and the diversity of external interference factors, different disciplines emphasize different priorities, and there is not yet a broad consensus on the definition of urban resilience (Wang et al., 2022). Overall, urban resilience encompasses technical resilience, social resilience, organizational resilience and economic resilience, among which technical resilience refers to the capacity of urban infrastructure to withstand disasters and recover from their impacts (Bruneau et al., 2003; McDaniels et al., 2008). Infrastructure, economy, society and systems have become the four internationally recognized dimensions for examining urban resilience (Jha et al., 2013). Among them, infrastructure is the “backbone” of the other three dimensions, and urban infrastructure has also become a key area of focus for building resilient cities. Therefore, it is a critical part of improving urban resilience to strengthen the scientific understanding of urban infrastructure resilience and to identify the level of resilience and obstacle factors of urban infrastructure, which is of great significance.

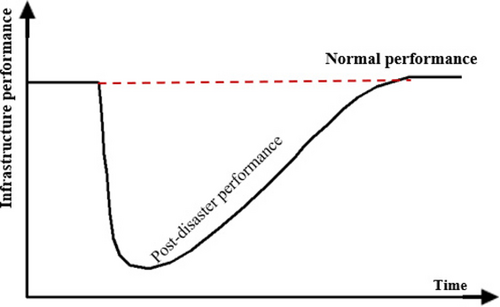

Common methods of urban infrastructure resilience evaluation fall into three categories. The first category is resilience evaluation method based on the curve of infrastructure system performance. This type of approach is based on the curve model of the infrastructure functional response process at the time of a disaster (see Fig. 1), and measures resilience by calculating the ratio of the area enclosed by the curve and the time axis after the disaster to that enclosed by the curve and the time axis under normal conditions (Turnquist and Vugrin, 2013; Li et al., 2016). The second category is resilience measurement method based on a network perspective. Considering the network characteristics of infrastructure (especially water, electricity, gas, communications, and transport), some scholars understood resilience from the perspective of network-flow theory, emphasizing the comprehensive capacities of a network to resist disasters, absorb losses, and recover from the impacts. With the number of products or services provided by the critical infrastructure as a metric for its performance level, they measured the resilience of an infrastructure network using a change curve of the performance level (Yan and Rong, 2021; Zhou et al., 2023). The third category is multi-index assessment methods. Such methods usually build an index system to characterize urban resilience with urban components as the core, or to build an index system that measures the pre-disaster resistance, recovery and adaptation capacities with resilience at different stages as the core, and adopt subjective and objective weighting methods for comprehensive assessment. Among the above three assessment paths, the first two pay attention to the physical and functional attributes of an infrastructure system itself, and often need to obtain precise parameters through engineering experiments. They are suitable for precise measurement of key infrastructure systems and are often used to measure the physical and structural resilience of urban infrastructure, yet they lack the consideration of social resilience. Urban infrastructure resilience is not only about physical engineering construction, but a comprehensive process covering multiple elements such as engineering construction and social governance, so a multi-index comprehensive assessment method is more suitable for comprehensive and systematic diagnosis and analysis of urban infrastructure resilience. In view of this, this paper adopts a multi-index comprehensive assessment model to measure the resilience of urban infrastructure in China, analyze its current characteristics, and identify the main obstacle factors to resilience, so as to provide a reference for promoting the construction of resilient cities in China.

Fig. 1. The curve of infrastructure system performance.

Source: Drawn according to Turnquist and Vugrin (2013), McDaniels et al. (2008), and Li et al. (2016).

2. Index System and Methods for Urban Infrastructure Resilience Assessment

2.1. Index system for urban infrastructure resilience assessment

With the increasing severe risk of climate change and the frequent occurrence of black swan events, the philosophy of national territorial space governance is gradually shifting from traditional disaster prevention to proactive adaptation and resilience building (Lv et al., 2021). In this context, strengthening urban resilience governance from a dynamic perspective has become a mainstream idea to improve urban resilience, and the investigation of urban infrastructure resilience should also pay attention to the whole process of uncertain events or disturbances. Urban infrastructure resilience can be understood as the capacities of urban infrastructure systems to resist disasters, absorb losses, and resume normal operations in a timely manner in the event of a disaster (Li et al., 2016). Xiang et al. (2021) believed that urban systems have the capacity to mitigate and adapt to disasters, and also have the capacity to recover quickly after disasters, and when it comes to urban infrastructure resilience, the emphasis is on the capacity of urban infrastructure to resume normal operation from natural disasters. The assessment and research of urban infrastructure resilience should include target setting, risk analysis, key points and weak points, targeted measures, measure effectiveness verification, etc., in order to continuously improve the robustness, resilience and adaptability of infrastructure systems (Wu and Lau, 2023). Based on the existing research results (Xiang et al., 2021), this paper establishes an index system for urban infrastructure resilience assessment consisting of three target layer factors, eight criterion layer variables and 26 specific indexes from the dimensions of pre-disaster prevention capacity, disaster resistance capacity and post-disaster recovery capacity, and calculates the weight coefficient of each index by using the Criteria Importance through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) weighting method, as shown in Table 1. Urban infrastructure includes energy supply, water supply and drainage, road transport, environmental sanitation, and communication. Limited to data availability, the index system in this paper does not take into account the communication infrastructure system. In addition, due to incomplete data at the city level, this paper only measures and analyzes at the provincial level (excluding Hong Kong S.A.R., Macao S.A.R. and Taiwan, China).

| Overall target | Target layer | Criterion layer variable (weight) | Index layer factor (Unit) | Nature of index | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban infrastructure resilience | Pre-disaster prevention capacity | Capital investment (0.1492) | Proportion of fixed asset investment in production and supply of electricity, gas and water (%) | 0.053 | |

| Proportion of fixed asset investment in transportation, warehousing and postal services (%) | 0.0447 | ||||

| Proportion of fixed asset investment in management of water conservancy, environmental and public facilities (%) | 0.0515 | ||||

| Observation and early warning (0.0909) | Density of seismic stations (station/10,000km2) | 0.0327 | |||

| Density of surface observation stations (station/10,000km2) | 0.027 | ||||

| Density of radar weather observation stations (station/10,000km2) | 0.0312 | ||||

| Disaster resistance capacity | Energy supply capacity (0.1539) | Natural gas supply capacity (m3/person) | 0.0327 | ||

| Power supply capacity (10,000kWh/person) | 0.0521 | ||||

| Installed capacity of standby coal-fired power units (MW/10,000 people) | 0.0399 | ||||

| Duration of average power outage per household (hours/household) | 0.0292 | ||||

| Water supply and drainage capacity (0.1144) | Comprehensive water supply capacity (10,000m3/day) | 0.038 | |||

| Daily urban sewage treatment capacity (m3/person) | 0.0426 | ||||

| Urban drainage pipe length (km/10,000 people) | 0.0338 | ||||

| Public transport capacity (0.1102) | Highway density (km/10,000 people) | 0.0424 | |||

| Railway freight turnover capacity (10,000tons km/km2) | 0.0391 | ||||

| Road freight turnover capacity (10,000tons km/10,000 people) | 0.0287 | ||||

| Post-disaster recovery capacity | R&D investment (0.0670) | Full-time equivalent (FTE) of R&D personnel (person year/10,000 people) | 0.0311 | ||

| Number of R&D projects (project/10,000 people) | 0.0359 | ||||

| Construction enterprise capacity (0.1895) | Number of construction enterprises (enterprise/10,000 people) | 0.0382 | |||

| Number of employees in construction enterprises (person/10,000 people) | 0.0433 | ||||

| Number of survey and design institutions (institution/1,000 people) | 0.0379 | ||||

| Number of construction supervision enterprises (enterprise/100 people) | 0.035 | ||||

| Number of enterprise-owned construction machinery and equipment (set/10,000 people) | 0.0351 | ||||

| Funding and staffing (0.1249) | Local fiscal and tax revenues (yuan/person) | 0.0313 | |||

| Number of employed workers in management of water conservancy, environmental and public facilities (worker/10,000 people) | 0.0395 | ||||

| Number of employed workers in production and supply of electricity, heat, gas and water (worker/10,000 people) | 0.0541 |

2.2. Data sources

The data in this paper are mainly from China Statistical Yearbook 2022, China Urban-Rural Construction Statistical Yearbook 2021, China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2021, China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology 2022, China Basic Statistical Units Yearbook 2022, China Statistical Yearbook on Construction 2022, China Taxation Yearbook 2022, and China Labor Statistical Yearbook 2022. The installed capacity of standby coal-fired power units and the duration of power outage per household are from the Annual Report of National Electricity Reliability 2021.

2.3. Methods for urban infrastructure resilience assessment

2.3.1. Data standardization

To comprehensively evaluate urban infrastructure resilience, it is necessary to process indexes first through standardization to achieve the dimensionless value. In the comprehensive assessment, positive indexes and negative indexes have different effects on the assessment results and needs to be treated differently. Suppose there are assessment objects and assessment indexes; represents the assessment object, represents the assessment index, and ; ; represents the th index value of the th assessment object.

Positive indexes are expressed as follows :

2.3.2. Determination of index weights

There are two types of methods to determine index weights: Subjective and objective. The subjective weighting method is more arbitrary and less scientific than the objective weighting method. Among many objective weighting methods, the CRITIC weighting method determines the index weights based on the variability and conflict between indexes, which not only considers the variability of the indexes themselves between different samples, but also takes into account the relationship between the indexes, containing more information, thus drawing more authentic and credible conclusions (Zhang and Wei, 2012; Zhao et al., 2021). Therefore, this paper uses the CRITIC weighting method to determine the weight coefficient of the index system for urban infrastructure resilience assessment. The calculation steps are as follows:

| (i) | The conflict between indexes and the amount of information of single indexes are, respectively, expressed as follows: (2.3) (2.4) | ||||

| (ii) | The weight coefficient is expressed as follows : (2.5) | ||||

2.3.3. Multi-index comprehensive assessment model

After data standardization and index weighting, the assessment of urban infrastructure resilience is carried out according to the following integrated assessment model (IAM) :

2.4. Method for identification of obstacle factors to urban infrastructure resilience

In this paper, the obstacle degree model (ODM) is introduced to measure the limiting effect of each index factor on urban infrastructure resilience, and to clarify the main obstacle factors to urban infrastructure resilience in China. The equation for calculating the obstacle degree is as follows (Liu et al., 2023):

3. Assessment Results of Urban Infrastructure Resilience in China

3.1. Current characteristics and structural differences of urban infrastructure resilience in China

According to the above method, the pre-disaster prevention capacity, disaster resistance capacity, post-disaster recovery capacity, and overall resilience level of urban infrastructure in China’s provinces and municipalities are calculated separately, with the results shown in Table 2. Overall, the resilience of urban infrastructure in China was generally low: The average urban infrastructure resilience of all provinces was only 0.2787, the median value was only 0.2556, and only 12 provinces (38.7% of the 31 provinces) exceeded the average value of urban infrastructure resilience. Most of the provinces were at medium and low levels, and only Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Tianjin had a resilience level greater than 0.4, which was at a high level. From the perspective of resilience grade, the mean values of the three resilience grades from high to low were 0.4388, 0.3047, and 0.2257, and the score of the high resilience group was much higher than that of the low resilience group, marking a large gap in the resilience level. From the perspective of spatial patterns, the spatial difference in urban infrastructure resilience was relatively significant: The resilience level of coastal regions was generally higher, and that of western and northeastern regions was lower. There were four provinces and municipalities with high resilience levels, including Beijing (0.4923), Shanghai (0.4398), Jiangsu (0.4160), and Tianjin (0.4071). There were 10 provinces with medium levels of resilience, including Hubei, Anhui, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Ningxia, Xizang, and the provinces in the coastal regions of southeast China. There were 17 provinces with low levels of resilience, mainly distributed in the inland regions of northeast, southwest, and northwest China.

| Province/Municipality | Resilience | Ranking | Grade | Province/Municipality | Resilience | Ranking | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.4923 | 1 | High | Inner Mongolia | 0.2543 | 17 | Low |

| Shanghai | 0.4398 | 2 | Qinghai | 0.2528 | 18 | ||

| Jiangsu | 0.4160 | 3 | Chongqing | 0.2460 | 19 | ||

| Tianjin | 0.4071 | 4 | Liaoning | 0.2428 | 20 | ||

| Zhejiang | 0.3435 | 5 | Medium | Hebei | 0.2400 | 21 | |

| Ningxia | 0.3416 | 6 | Jilin | 0.2323 | 22 | ||

| Guangdong | 0.3281 | 7 | Sichuan | 0.2287 | 23 | ||

| Shandong | 0.3124 | 8 | Hunan | 0.2245 | 24 | ||

| Fujian | 0.3055 | 9 | Yunnan | 0.2235 | 25 | ||

| Xizang | 0.2982 | 10 | Jiangxi | 0.2164 | 26 | ||

| Hubei | 0.2846 | 11 | Xinjiang | 0.2065 | 27 | ||

| Shaanxi | 0.2837 | 12 | Gansu | 0.2021 | 28 | ||

| Shanxi | 0.2757 | 13 | Heilongjiang | 0.1912 | 29 | ||

| Anhui | 0.2738 | 14 | Guangxi | 0.1859 | 30 | ||

| Hainan | 0.2622 | 15 | Low | Guizhou | 0.1714 | 31 | |

| Henan | 0.2556 | 16 |

According to the grading differences of pre-disaster prevention capacity, disaster resilience capacity and post-disaster recovery capacity, the structure of urban infrastructure resilience can be further divided into four types: High-level balanced, medium-level balanced, low-level balanced, and single-dimension dominated types (see Table 3). Among them, there were 14 medium-level balanced provinces/municipalities, accounting for 45.16%; eight low-level balanced provinces/municipalities, accounting for 25.81%; six high-level balanced provinces/municipalities, accounting for 19.35%; and three single-dimension dominated provinces/municipalities, accounting for 9.68%.

| Type | Province/Municipality | |

|---|---|---|

| High-level balanced type | High prevention–high resistance–high recovery | Beijing, Shanghai |

| High prevention–high resistance–medium recovery | Tianjin, Ningxia | |

| Medium prevention–high resistance–high recovery | Jiangsu, Zhejiang | |

| Medium-level balanced type | Medium prevention–low resistance–medium recovery | Yunnan |

| Medium prevention–medium resistance–medium recovery | Shanxi, Anhui, Henan, Hainan, Qinghai | |

| Medium prevention – high resistance – medium recovery | Shandong, Guangdong | |

| Medium prevention–medium resistance–high recovery | Fujian | |

| Medium prevention–medium resistance–low recovery | Liaoning | |

| Low prevention–medium resistance–medium recovery | Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Hubei, Sichuan | |

| Low-level balanced type | Low prevention–low resistance–low resilience | Guizhou |

| Medium prevention–low resistance–low resilience | Heilongjiang, Guangxi | |

| Low prevention–low resistance–medium resilience | Jiangxi, Hunan, Gansu | |

| Low prevention–medium resistance–low resilience | Chongqing, Xinjiang | |

| Single-dimension dominated type | High prevention–medium resistance–low resilience | Hebei |

| Medium prevention–low resistance–high resilience | Xizang | |

| Low prevention–medium resistance–high resilience | Shaanxi | |

From the perspective of spatial patterns, the structure of urban infrastructure resilience for disaster prevention and mitigation varied greatly across China’s provinces and municipalities. The high-level balanced provinces and municipalities are mainly distributed in the eastern regions including the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and the Yangtze River Delta region. Among them, Beijing and Shanghai were not only generally high in resilience level, but also classified as high prevention–high resistance–high recovery type, with their resilience levels consistent with their socio-economic development and urbanization levels. Tianjin’s post-disaster recovery capacity lagged behind its pre-disaster prevention and resistance capacities. Jiangsu and Zhejiang were classified as the medium prevention–high resistance–high recovery type, which should pay more attention to pre-disaster early warning and increase capital investment to improve pre-disaster prevention capacities. The medium-level balanced provinces and municipalities are great in number and widely distributed. Their prevention, resistance and recovery capacities were at a medium level, with small differences between the three capacities. Among them, Fujian was classified as the medium prevention–medium resistance–high recovery type, which should further strengthen the capital investment before a disaster occurs, and improve the capacity of observation and early warning and the capacity to ensure energy supply, water supply and drainage, and public transport upon the occurrence of a disaster. Shandong and Guangdong were classified as the medium prevention–high resistance–medium recovery type, which should further strengthen the monitoring and early warning of meteorological, flood and geological disasters, refine the contingency plans and measures for various key areas, and improve the coping capacity after a disaster. The low-level balanced provinces and municipalities are mainly distributed in the central and western regions. Such provinces and municipalities need to accumulate experience in disaster resistance, improve disaster prevention and mitigation capacities, and enhance necessary elements such as infrastructure, funding, scientific and technological resources so as to improve the resilience in terms of disaster prevention and mitigation in a targeted manner. Single-dimension dominated provinces and municipalities include Hebei, Xizang, and Shaanxi. Such provinces and municipalities should steadily improve their relatively backward capacities, make up for their shortcomings, break through the bottleneck by increasing investment and mobilizing resources to tackle key problems, promote balanced and stable development in all aspects, and achieve the substantial improvement of resilience.

3.2. Pre-disaster prevention capacity

In terms of pre-disaster prevention capacity, Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Ningxia, Hebei, and Xizang scored higher, while Guizhou scored the lowest (see Table 4). Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei attached great importance to infrastructure construction and upgrading, and invested more money in improving the production and supply capacity of electricity, gas and water resources, thereby enhancing their ability to cope with disasters. These regions also invested relatively more in the water conservancy, environmental, and public facilities. The construction and maintenance of water conservancy facilities help prevent floods, droughts, and water pollution. Investments in environmental and public facilities can also help improve the capacity of regional emergency services and mitigate the environmental damage of disasters and the impact on public life. In addition, the relatively high density of meteorological, geology, and hydrological observation stations in these regions can provide more comprehensive natural disaster monitoring data, thus providing more accurate and timely disaster early warning and helping people take preventive measures in advance. Ningxia and Xizang cover a variety of landforms including plateaus, mountains, grasslands, and deserts, thus facing a wide variety of disasters. The local governments invested a lot of money in pre-disaster prevention and management, and established sound observation and early warning systems for different types of disasters.

| Province/Municipality | Capital investment | Observation and early warning | Pre-disaster prevention capacity | Ranking | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai | 0.0572 | 0.0751 | 0.1323 | 1 | High |

| Beijing | 0.0349 | 0.0758 | 0.1106 | 2 | |

| Tianjin | 0.0480 | 0.0578 | 0.1058 | 3 | |

| Ningxia | 0.0832 | 0.0107 | 0.0939 | 4 | |

| Hebei | 0.0782 | 0.0146 | 0.0928 | 5 | |

| Xizang | 0.0846 | 0.0003 | 0.0849 | 6 | Medium |

| Henan | 0.0662 | 0.0129 | 0.0791 | 7 | |

| Fujian | 0.0562 | 0.0215 | 0.0777 | 8 | |

| Hainan | 0.0509 | 0.0265 | 0.0773 | 9 | |

| Guangdong | 0.0553 | 0.0205 | 0.0758 | 10 | |

| Jiangsu | 0.0557 | 0.0189 | 0.0747 | 11 | |

| Shandong | 0.0535 | 0.0207 | 0.0741 | 12 | |

| Zhejiang | 0.0483 | 0.0253 | 0.0737 | 13 | |

| Anhui | 0.0575 | 0.0136 | 0.0711 | 14 | |

| Guangxi | 0.0578 | 0.0118 | 0.0696 | 15 | |

| Qinghai | 0.0680 | 0.0005 | 0.0685 | 16 | |

| Yunnan | 0.0580 | 0.0098 | 0.0678 | 17 | |

| Heilongjiang | 0.0633 | 0.0044 | 0.0677 | 18 | |

| Liaoning | 0.0562 | 0.0113 | 0.0675 | 19 | |

| Shanxi | 0.0553 | 0.0107 | 0.0660 | 20 | |

| Sichuan | 0.0575 | 0.0059 | 0.0634 | 21 | Low |

| Jiangxi | 0.0508 | 0.0123 | 0.0631 | 22 | |

| Jilin | 0.0501 | 0.0102 | 0.0603 | 23 | |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.0573 | 0.0016 | 0.0589 | 24 | |

| Chongqing | 0.0473 | 0.0116 | 0.0589 | 25 | |

| Hubei | 0.0486 | 0.0099 | 0.0585 | 26 | |

| Shaanxi | 0.0449 | 0.0102 | 0.0550 | 27 | |

| Hunan | 0.0441 | 0.0106 | 0.0547 | 28 | |

| Gansu | 0.0490 | 0.0049 | 0.0539 | 29 | |

| Xinjiang | 0.0517 | 0.0009 | 0.0526 | 30 | |

| Guizhou | 0.0243 | 0.0110 | 0.0353 | 31 |

3.3. Disaster resistance capacity

In terms of disaster resistance capacity, Tianjin, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Ningxia, Zhejiang, and Shandong scored higher, while Yunnan, Guangxi, Gansu, Heilongjiang, and Xizang scored lower (see Table 5). Tianjin and Beijing have a strong energy supply capacity, which is mainly attributed to their developed economy, abundant energy reserves, and diversified and stable energy sources, so that the stable operation of the energy system can be guaranteed in the event of disasters. These regions also have a larger water supply network and a more complete drainage system, which can provide sufficient drinking and domestic water, and at the same time can effectively reduce the impact of floods and other disasters on the city. These regions also have well-developed transportation systems, high road density, full-fledged public transportation systems, where multiple airports or ports ensure high cargo turnover and strong cargo transportation capacity, allowing for the faster transport of rescue personnel, supplies and equipment, and the provision of the necessary support for disaster relief.

| Province/Municipality | Energy supply capacity | Water supply and drainage capacity | Public transport capacity | Disaster resistance capacity | Ranking | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tianjin | 0.0565 | 0.0756 | 0.0690 | 0.2011 | 1 | High |

| Beijing | 0.0620 | 0.0595 | 0.0677 | 0.1892 | 2 | |

| Shanghai | 0.0485 | 0.0636 | 0.0698 | 0.1819 | 3 | |

| Jiangsu | 0.0557 | 0.0786 | 0.0348 | 0.1691 | 4 | |

| Guangdong | 0.0448 | 0.0952 | 0.0270 | 0.1670 | 5 | |

| Ningxia | 0.1241 | 0.0180 | 0.0136 | 0.1558 | 6 | |

| Zhejiang | 0.0522 | 0.0630 | 0.0292 | 0.1444 | 7 | |

| Shandong | 0.0487 | 0.0440 | 0.0503 | 0.1430 | 8 | |

| Hubei | 0.0409 | 0.0515 | 0.0354 | 0.1278 | 9 | Medium |

| Liaoning | 0.0387 | 0.0592 | 0.0250 | 0.1229 | 10 | |

| Chongqing | 0.0361 | 0.0387 | 0.0473 | 0.1220 | 11 | |

| Anhui | 0.0438 | 0.0370 | 0.0408 | 0.1216 | 12 | |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.1013 | 0.0151 | 0.0037 | 0.1202 | 13 | |

| Shanxi | 0.0617 | 0.0135 | 0.0351 | 0.1103 | 14 | |

| Henan | 0.0360 | 0.0193 | 0.0478 | 0.1031 | 15 | |

| Qinghai | 0.0812 | 0.0203 | 0.0009 | 0.1024 | 16 | |

| Shaanxi | 0.0503 | 0.0250 | 0.0247 | 0.1000 | 17 | |

| Hebei | 0.0404 | 0.0067 | 0.0497 | 0.0969 | 18 | |

| Jilin | 0.0335 | 0.0483 | 0.0130 | 0.0948 | 19 | |

| Fujian | 0.0480 | 0.0261 | 0.0194 | 0.0936 | 20 | |

| Sichuan | 0.0371 | 0.0371 | 0.0164 | 0.0906 | 21 | |

| Hainan | 0.0322 | 0.0354 | 0.0225 | 0.0900 | 22 | |

| Xinjiang | 0.0747 | 0.0131 | 0.0013 | 0.0891 | 23 | |

| Hunan | 0.0302 | 0.0310 | 0.0257 | 0.0869 | 24 | Low |

| Guizhou | 0.0461 | 0.0145 | 0.0244 | 0.0850 | 25 | |

| Jiangxi | 0.0341 | 0.0184 | 0.0293 | 0.0818 | 26 | |

| Yunnan | 0.0413 | 0.0200 | 0.0149 | 0.0761 | 27 | |

| Guangxi | 0.0295 | 0.0243 | 0.0151 | 0.0689 | 28 | |

| Gansu | 0.0516 | 0.0074 | 0.0088 | 0.0677 | 29 | |

| Heilongjiang | 0.0330 | 0.0258 | 0.0071 | 0.0659 | 30 | |

| Xizang | 0.0077 | 0.0237 | 0.0000 | 0.0314 | 31 |

3.4. Post-disaster recovery capacity

In terms of post-disaster recovery capacity, Beijing, Xizang, Jiangsu, Fujian, Shaanxi, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Tianjin scored higher, while Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Guizhou, Hebei, and Guangxi scored lower (see Table 6). Regions, such as Beijing and Jiangsu, are more densely packed with scientific research institutions, colleges and universities, and have more researchers. They have advantages in terms of expertise, research and development capacities and technical support, and are able to invest more resources and talents in researching post-disaster recovery technologies and methods. Construction enterprises in these regions often have stronger technical capacities and rich experience that enable them to organize and implement disaster recovery and upgrading more quickly. In addition, regions such as Beijing and Jiangsu, with their developed economies and higher fiscal and tax revenues, are able to provide more fiscal inputs to support post-disaster recovery and upgrading, and these regions have more professionals in infrastructure construction and maintenance, which can better ensure the supply and maintenance of infrastructure needed after a disaster. Xizang is home to a unique plateau environment, to which scientific research institutions and researchers pay more attention in relevant studies, which can provide scientific basis and solutions for post-disaster recovery and improvement. Due to the frequent occurrence of natural disasters, enterprises, governments, and residents have also accumulated rich experience in coping with and recovering from disasters, which is conducive to the post-disaster recovery and upgrading of urban infrastructure.

| Province/Municipality | R & D investment | Construction enterprise capacity | Funding and staffing | Post-disaster recovery capacity | Ranking | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.0527 | 0.0652 | 0.0746 | 0.1925 | 1 | High |

| Xizang | 0.0014 | 0.1046 | 0.0759 | 0.1819 | 2 | |

| Jiangsu | 0.0443 | 0.1132 | 0.0148 | 0.1723 | 3 | |

| Fujian | 0.0239 | 0.0914 | 0.0189 | 0.1342 | 4 | |

| Shaanxi | 0.0148 | 0.0792 | 0.0345 | 0.1286 | 5 | |

| Shanghai | 0.0317 | 0.0356 | 0.0584 | 0.1257 | 6 | |

| Zhejiang | 0.0490 | 0.0606 | 0.0160 | 0.1256 | 7 | |

| Tianjin | 0.0322 | 0.0382 | 0.0299 | 0.1003 | 8 | Medium |

| Shanxi | 0.0061 | 0.0467 | 0.0466 | 0.0994 | 9 | |

| Hubei | 0.0171 | 0.0621 | 0.0192 | 0.0983 | 10 | |

| Shandong | 0.0213 | 0.0520 | 0.0221 | 0.0954 | 11 | |

| Hainan | 0.0089 | 0.0294 | 0.0566 | 0.0949 | 12 | |

| Ningxia | 0.0066 | 0.0329 | 0.0525 | 0.0920 | 13 | |

| Guangdong | 0.0513 | 0.0192 | 0.0149 | 0.0854 | 14 | |

| Hunan | 0.0171 | 0.0479 | 0.0179 | 0.0830 | 15 | |

| Qinghai | 0.0009 | 0.0458 | 0.0351 | 0.0819 | 16 | |

| Anhui | 0.0205 | 0.0506 | 0.0100 | 0.0811 | 17 | |

| Gansu | 0.0030 | 0.0291 | 0.0484 | 0.0805 | 18 | |

| Yunnan | 0.0040 | 0.0494 | 0.0263 | 0.0797 | 19 | |

| Jilin | 0.0084 | 0.0273 | 0.0415 | 0.0772 | 20 | |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.0020 | 0.0183 | 0.0549 | 0.0752 | 21 | |

| Sichuan | 0.0149 | 0.0374 | 0.0224 | 0.0747 | 22 | |

| Henan | 0.0090 | 0.0415 | 0.0228 | 0.0733 | 23 | |

| Jiangxi | 0.0208 | 0.0361 | 0.0146 | 0.0715 | 24 | |

| Chongqing | 0.0188 | 0.0374 | 0.0089 | 0.0651 | 25 | Low |

| Xinjiang | 0.0002 | 0.0130 | 0.0516 | 0.0648 | 26 | |

| Heilongjiang | 0.0056 | 0.0079 | 0.0441 | 0.0576 | 27 | |

| Liaoning | 0.0097 | 0.0171 | 0.0257 | 0.0525 | 28 | |

| Guizhou | 0.0053 | 0.0235 | 0.0222 | 0.0511 | 29 | |

| Hebei | 0.0069 | 0.0253 | 0.0182 | 0.0505 | 30 | |

| Guangxi | 0.0037 | 0.0241 | 0.0195 | 0.0474 | 31 |

4. Analysis of Obstacle Factors to the Resilience of Urban Infrastructure in China

4.1. Analysis of obstacle factors in the criterion layer

According to the aforementioned equation for calculating obstacle degree, the obstacle factors to China’s urban infrastructure resilience are calculated, with the results shown in Table 7. According to the criterion that the main obstacle factors in the criterion layer are identified as those with the obstacle degree exceeding the average value of 12.5%, it can be found that the main obstacle factors to urban infrastructure resilience varied across provinces and municipalities, but almost all of them involve three dimensions: Pre-disaster prevention capacity, disaster resistance capacity, and post-disaster recovery capacity. Specifically, the most frequent obstacle factor to urban infrastructure resilience was the construction enterprise capacity, with a total of 30 provinces and municipalities, accounting for 96.77%. It was followed by energy supply capacity (27 provinces and municipalities, accounting for 87.10%), capital investment (19 provinces and municipalities, accounting for 61.29%), funding and staffing (18 provinces and municipalities, accounting for 58.06%), water supply and drainage capacity, and public transport capacity (10 provinces and municipalities, accounting for 32.26%). In other words, the capacities to construct infrastructure recovery projects and to ensure energy supply, which represent the construction enterprise capacity, are two of the most important obstacle factors restricting China’s urban infrastructure resilience.

| Unit: % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-disaster prevention capacity | Disaster resistance capacity | Post-disaster recovery capacity | ||||||

| Province/Municipality | Capital investment | Observation and early warning | Energy supply capacity | Water supply and drainage capacity | Public transport capacity | R&D investment | Construction enterprise capacity | Funding and staffing |

| Beijing | 22.52 | 2.98 | 18.10 | 10.82 | 8.37 | 2.82 | 24.48 | 9.91 |

| Tianjin | 17.07 | 5.59 | 16.43 | 6.55 | 6.95 | 5.87 | 25.53 | 16.02 |

| Hebei | 9.34 | 10.04 | 14.93 | 14.17 | 7.96 | 7.90 | 21.61 | 14.04 |

| Shanxi | 12.96 | 11.07 | 12.73 | 13.93 | 10.37 | 8.41 | 19.71 | 10.82 |

| Inner Mongolia | 12.33 | 11.97 | 7.05 | 13.31 | 14.28 | 8.72 | 22.95 | 9.38 |

| Liaoning | 12.29 | 10.52 | 15.21 | 7.29 | 11.25 | 7.57 | 22.76 | 13.10 |

| Jilin | 12.90 | 10.51 | 15.68 | 8.61 | 12.66 | 7.63 | 21.13 | 10.86 |

| Heilongjiang | 10.62 | 10.69 | 14.94 | 10.95 | 12.75 | 7.60 | 22.45 | 10.00 |

| Shanghai | 16.43 | 2.82 | 18.81 | 9.08 | 7.21 | 6.31 | 27.47 | 11.88 |

| Jiangsu | 16.01 | 12.32 | 16.82 | 6.13 | 12.91 | 3.89 | 13.06 | 18.86 |

| Zhejiang | 15.37 | 9.99 | 15.50 | 7.84 | 12.33 | 2.75 | 19.64 | 16.60 |

| Anhui | 12.63 | 10.64 | 15.16 | 10.66 | 9.56 | 6.41 | 19.13 | 15.82 |

| Fujian | 13.39 | 9.99 | 15.24 | 12.71 | 13.07 | 6.20 | 14.13 | 15.26 |

| Jiangxi | 12.55 | 10.03 | 15.29 | 12.25 | 10.33 | 5.90 | 19.58 | 14.07 |

| Shandong | 13.93 | 10.22 | 15.30 | 10.24 | 8.72 | 6.65 | 19.99 | 14.96 |

| Henan | 11.15 | 10.48 | 15.84 | 12.77 | 8.39 | 7.79 | 19.89 | 13.71 |

| Hubei | 14.06 | 11.33 | 15.80 | 8.79 | 10.45 | 6.98 | 17.81 | 14.78 |

| Hunan | 13.56 | 10.35 | 15.95 | 10.76 | 10.90 | 6.43 | 18.26 | 13.80 |

| Guangdong | 13.98 | 10.48 | 16.24 | 2.85 | 12.39 | 2.33 | 25.35 | 16.38 |

| Guangxi | 11.23 | 9.72 | 15.28 | 11.06 | 11.68 | 7.78 | 20.31 | 12.94 |

| Hainan | 13.33 | 8.73 | 16.50 | 10.71 | 11.89 | 7.88 | 21.70 | 9.26 |

| Chongqing | 13.52 | 10.52 | 15.63 | 10.04 | 8.35 | 6.39 | 20.18 | 15.38 |

| Sichuan | 11.89 | 11.02 | 15.14 | 10.02 | 12.16 | 6.75 | 19.72 | 13.29 |

| Guizhou | 15.08 | 9.64 | 13.01 | 12.05 | 10.35 | 7.44 | 20.03 | 12.39 |

| Yunnan | 11.74 | 10.45 | 14.51 | 12.16 | 12.28 | 8.12 | 18.04 | 12.70 |

| Xizang | 9.21 | 12.90 | 20.83 | 12.92 | 15.70 | 9.35 | 12.10 | 6.99 |

| Shaanxi | 14.57 | 11.27 | 14.47 | 12.47 | 11.94 | 7.28 | 15.40 | 12.61 |

| Gansu | 12.56 | 10.77 | 12.83 | 13.41 | 12.71 | 8.02 | 20.11 | 9.59 |

| Qinghai | 10.87 | 12.10 | 9.73 | 12.59 | 14.63 | 8.84 | 19.23 | 12.01 |

| Ningxia | 10.03 | 12.18 | 4.52 | 14.64 | 14.68 | 9.18 | 23.79 | 10.99 |

| Xinjiang | 12.29 | 11.34 | 9.98 | 12.76 | 13.72 | 8.41 | 22.24 | 9.24 |

4.2. Analysis of obstacle factors in the index layer

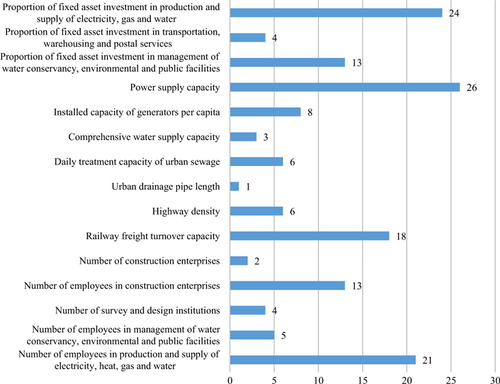

Due to the large number of index layer factors, this paper considers the top five indexes of obstacle degree as the main obstacle factors, and the occurrence frequency of each specific index as the main obstacle factors is shown in Fig. 2. It can be seen that the most frequent obstacle factors are, in descending order, power supply capacity, the proportion of fixed asset investment in production, and supply of electricity, gas and water, the number of employed workers in production and supply of electricity, heat, gas and water, railway freight turnover capacity, the proportion of fixed asset investment in management of water conservancy, environmental and public facilities, and the number of employees in construction enterprises, indicating that the supply of energy and water resources should be the focus of urban infrastructure resilience improvement.

Fig. 2. The occurrence frequency of factors in the index layer as the main obstacle factors.

Note: The occurrence frequency of 11 indexes, including density of seismic stations, as the main obstacle factors is 0, so it is not shown in the figure. Source: Made by the authors.

From the perspective of pre-disaster prevention capacity (see Table 8), the proportion of fixed asset investment in the production and supply of electricity, gas, and water registered the highest frequency (24 provinces), followed by the proportion of fixed asset investment in management of water conservancy, environmental and public facilities (13 provinces). It can be seen that attention should be paid to the pre-disaster prevention capacity in terms of electricity, gas, and water resources supply, by increasing the fixed asset investment in the production and supply of electricity, gas, and water, and in the management of water conservancy, environmental, and public facilities. The regions where the proportion of fixed asset investment in transportation, warehousing, and postal services is the main obstacle factor include Inner Mongolia, Yunnan, Xizang, and Qinghai, while the densities of seismic stations, surface observation stations, and radar weather observation stations are all small in obstacle degree and do not constitute the main obstacle factors.

| Unit: % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital investment | Observation and early warning | |||||

| Province/Municipality | Proportion of fixed asset investment in production and supply of electricity, gas and water | Proportion of fixed asset investment in transportation, warehousing and postal services | Proportion of fixed asset investment in management of water conservancy, environmental and public facilities | Density of seismic stations | Density of surface observation stations | Density of radar weather observation stations |

| Beijing | 0.0964 | 0.0403 | 0.0886 | 0.0000 | 0.0298 | 0.0000 |

| Tianjin | 0.0870 | 0.0000 | 0.0837 | 0.0153 | 0.0280 | 0.0126 |

| Hebei | 0.0447 | 0.0431 | 0.0057 | 0.0385 | 0.0261 | 0.0359 |

| Shanxi | 0.0440 | 0.0279 | 0.0578 | 0.0414 | 0.0302 | 0.0391 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.0243 | 0.0584 | 0.0405 | 0.0436 | 0.0348 | 0.0413 |

| Liaoning | 0.0476 | 0.0262 | 0.0491 | 0.0404 | 0.0271 | 0.0377 |

| Jilin | 0.0566 | 0.0206 | 0.0518 | 0.0412 | 0.0265 | 0.0375 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.0342 | 0.0306 | 0.0414 | 0.0399 | 0.0299 | 0.0371 |

| Shanghai | 0.0842 | 0.0283 | 0.0518 | 0.0126 | 0.0000 | 0.0157 |

| Jiangsu | 0.0808 | 0.0170 | 0.0623 | 0.0494 | 0.0323 | 0.0415 |

| Zhejiang | 0.0807 | 0.0095 | 0.0635 | 0.0431 | 0.0275 | 0.0293 |

| Anhui | 0.0627 | 0.0196 | 0.0440 | 0.0426 | 0.0276 | 0.0362 |

| Fujian | 0.0697 | 0.0197 | 0.0445 | 0.0410 | 0.0266 | 0.0323 |

| Jiangxi | 0.0653 | 0.0208 | 0.0394 | 0.0412 | 0.0250 | 0.0342 |

| Shandong | 0.0591 | 0.0261 | 0.0541 | 0.0409 | 0.0260 | 0.0353 |

| Henan | 0.0644 | 0.0251 | 0.0220 | 0.0416 | 0.0266 | 0.0366 |

| Hubei | 0.0724 | 0.0220 | 0.0462 | 0.0445 | 0.0302 | 0.0387 |

| Hunan | 0.0635 | 0.0196 | 0.0525 | 0.0415 | 0.0263 | 0.0357 |

| Guangdong | 0.0729 | 0.0169 | 0.0500 | 0.0454 | 0.0281 | 0.0313 |

| Guangxi | 0.0557 | 0.0210 | 0.0356 | 0.0390 | 0.0244 | 0.0338 |

| Hainan | 0.0699 | 0.0175 | 0.0459 | 0.0398 | 0.0192 | 0.0283 |

| Chongqing | 0.0692 | 0.0079 | 0.0581 | 0.0418 | 0.0275 | 0.0359 |

| Sichuan | 0.0670 | 0.0125 | 0.0394 | 0.0405 | 0.0314 | 0.0383 |

| Guizhou | 0.0620 | 0.0267 | 0.0622 | 0.0392 | 0.0246 | 0.0326 |

| Yunnan | 0.0606 | 0.0569 | 0.0000 | 0.0376 | 0.0291 | 0.0379 |

| Xizang | 0.0000 | 0.0596 | 0.0325 | 0.0466 | 0.0380 | 0.0445 |

| Shaanxi | 0.0667 | 0.0257 | 0.0533 | 0.0429 | 0.0293 | 0.0405 |

| Gansu | 0.0509 | 0.0274 | 0.0473 | 0.0387 | 0.0315 | 0.0375 |

| Qinghai | 0.0572 | 0.0386 | 0.0129 | 0.0434 | 0.0361 | 0.0414 |

| Ningxia | 0.0139 | 0.0679 | 0.0185 | 0.0461 | 0.0329 | 0.0428 |

| Xinjiang | 0.0369 | 0.0424 | 0.0436 | 0.0408 | 0.0335 | 0.0391 |

In terms of disaster resistance capacity (see Table 9), the most frequent obstacle factor was power supply capacity (26 provinces), followed by railway freight turnover capacity (18 provinces). It can be seen that attention should be paid to the role of power supply and railway freight turnover capacity in enhancing the disaster resistance capacity of urban infrastructure. Provinces and municipalities where the comprehensive water supply capacity is a main obstacle factor include Shaanxi, Qinghai, and Ningxia, probably due to the relative shortage of water resources and the predominance of heavy industry in the industrial structure. In addition, the proportion of urban drainage pipe length only poses an obstacle factor to the urban infrastructure resilience in Ningxia, where the natural gas supply capacity, duration of power outage per household, and road freight turnover capacity are all small in obstacle degree and do not constitute the main obstacle factors.

| Unit: % | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy supply capacity | Water supply and drainage capacity | Public transport capacity | ||||||||

| Province/Municipality | Natural gas supply capacity | Power supply capacity | Installed capacity of standby coal-fired power units | Duration of power outage per household | Comprehensive water supply capacity | Daily treatment capacity of urban sewage | Urban drainage pipe length | Highway density | Railway freight turnover capacity | Road freight turnover capacity |

| Beijing | 0.0000 | 0.1026 | 0.0781 | 0.0003 | 0.0633 | 0.0000 | 0.0448 | 0.0331 | 0.0000 | 0.0506 |

| Tianjin | 0.0322 | 0.0785 | 0.0528 | 0.0008 | 0.0576 | 0.0079 | 0.0000 | 0.0323 | 0.0053 | 0.0318 |

| Hebei | 0.0344 | 0.0598 | 0.0454 | 0.0097 | 0.0412 | 0.0561 | 0.0445 | 0.0300 | 0.0223 | 0.0273 |

| Shanxi | 0.0389 | 0.0451 | 0.0333 | 0.0100 | 0.0480 | 0.0471 | 0.0442 | 0.0366 | 0.0324 | 0.0348 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.0354 | 0.0104 | 0.0136 | 0.0111 | 0.0468 | 0.0533 | 0.0330 | 0.0547 | 0.0501 | 0.0381 |

| Liaoning | 0.0399 | 0.0607 | 0.0443 | 0.0073 | 0.0349 | 0.0019 | 0.0361 | 0.0357 | 0.0431 | 0.0337 |

| Jilin | 0.0377 | 0.0607 | 0.0431 | 0.0153 | 0.0424 | 0.0126 | 0.0311 | 0.0430 | 0.0480 | 0.0356 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.0384 | 0.0591 | 0.0427 | 0.0092 | 0.0388 | 0.0339 | 0.0369 | 0.0459 | 0.0465 | 0.0351 |

| Shanghai | 0.0397 | 0.0884 | 0.0600 | 0.0000 | 0.0489 | 0.0043 | 0.0375 | 0.0064 | 0.0657 | 0.0000 |

| Jiangsu | 0.0387 | 0.0740 | 0.0532 | 0.0023 | 0.0097 | 0.0309 | 0.0208 | 0.0273 | 0.0627 | 0.0391 |

| Zhejiang | 0.0354 | 0.0670 | 0.0505 | 0.0022 | 0.0294 | 0.0241 | 0.0248 | 0.0303 | 0.0564 | 0.0367 |

| Anhui | 0.0399 | 0.0612 | 0.0433 | 0.0072 | 0.0390 | 0.0368 | 0.0308 | 0.0149 | 0.0475 | 0.0331 |

| Fujian | 0.0380 | 0.0610 | 0.0476 | 0.0057 | 0.0428 | 0.0450 | 0.0393 | 0.0375 | 0.0544 | 0.0388 |

| Jiangxi | 0.0369 | 0.0614 | 0.0453 | 0.0093 | 0.0411 | 0.0463 | 0.0351 | 0.0253 | 0.0466 | 0.0314 |

| Shandong | 0.0383 | 0.0627 | 0.0497 | 0.0023 | 0.0301 | 0.0434 | 0.0288 | 0.0128 | 0.0446 | 0.0298 |

| Henan | 0.0375 | 0.0649 | 0.0465 | 0.0094 | 0.0364 | 0.0480 | 0.0433 | 0.0172 | 0.0379 | 0.0288 |

| Hubei | 0.0387 | 0.0616 | 0.0489 | 0.0088 | 0.0328 | 0.0226 | 0.0325 | 0.0188 | 0.0484 | 0.0373 |

| Hunan | 0.0386 | 0.0640 | 0.0477 | 0.0092 | 0.0369 | 0.0313 | 0.0393 | 0.0278 | 0.0457 | 0.0355 |

| Guangdong | 0.0377 | 0.0696 | 0.0527 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0090 | 0.0195 | 0.0296 | 0.0559 | 0.0384 |

| Guangxi | 0.0357 | 0.0561 | 0.0455 | 0.0155 | 0.0389 | 0.0369 | 0.0348 | 0.0382 | 0.0450 | 0.0336 |

| Hainan | 0.0433 | 0.0640 | 0.0500 | 0.0076 | 0.0498 | 0.0320 | 0.0254 | 0.0278 | 0.0525 | 0.0386 |

| Chongqing | 0.0340 | 0.0659 | 0.0487 | 0.0077 | 0.0418 | 0.0314 | 0.0272 | 0.0000 | 0.0487 | 0.0348 |

| Sichuan | 0.0346 | 0.0562 | 0.0503 | 0.0103 | 0.0320 | 0.0378 | 0.0303 | 0.0366 | 0.0486 | 0.0364 |

| Guizhou | 0.0336 | 0.0493 | 0.0382 | 0.0091 | 0.0415 | 0.0412 | 0.0379 | 0.0261 | 0.0436 | 0.0338 |

| Yunnan | 0.0421 | 0.0454 | 0.0479 | 0.0097 | 0.0439 | 0.0427 | 0.0350 | 0.0375 | 0.0491 | 0.0362 |

| Xizang | 0.0465 | 0.0634 | 0.0568 | 0.0416 | 0.0541 | 0.0317 | 0.0433 | 0.0604 | 0.0557 | 0.0409 |

| Shaanxi | 0.0324 | 0.0578 | 0.0427 | 0.0118 | 0.0456 | 0.0339 | 0.0453 | 0.0378 | 0.0436 | 0.0380 |

| Gansu | 0.0288 | 0.0465 | 0.0429 | 0.0100 | 0.0441 | 0.0517 | 0.0383 | 0.0465 | 0.0452 | 0.0354 |

| Qinghai | 0.0113 | 0.0272 | 0.0472 | 0.0116 | 0.0498 | 0.0457 | 0.0303 | 0.0562 | 0.0517 | 0.0384 |

| Ningxia | 0.0354 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0098 | 0.0547 | 0.0408 | 0.0509 | 0.0503 | 0.0552 | 0.0413 |

| Xinjiang | 0.0217 | 0.0191 | 0.0401 | 0.0189 | 0.0423 | 0.0467 | 0.0386 | 0.0526 | 0.0485 | 0.0361 |

In terms of post-disaster recovery capacity (see Table 10), the most frequent obstacle factor is the number of employed workers in production and supply of electricity, heat, gas and water (21 provinces), followed by the number of employees in construction enterprises (13 provinces). It can be seen that attention should be paid to the employment of workers in the production and supply of electricity, heat, gas and water, as well as in the construction enterprises, so as to improve the post-disaster recovery capacity of urban infrastructure. Provinces and municipalities where the number of construction enterprises is the main obstacle factor include Heilongjiang and Shanghai, while the FTE of R&D personnel, the number of R&D projects, the number of construction supervision enterprises, the number of enterprise-owned construction machinery and equipment and the local fiscal and tax revenues are all small in obstacle degree and do not constitute the main obstacle factors.

| Unit: % | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R & D investment | Construction enterprise capacity | Funding and staffing | ||||||||

| Province/Municipality | FTE of R&D personnel | Number of R&D projects | Number of construction enterprises | Number of employees in construction enterprises | Number of survey and design institutions | Number of construction supervision enterprises | Number of enterprise-owned construction machinery and equipment | Local fiscal and tax revenues | Number of employees in management of water conservancy, environmental and public facilities | Number of employees in production and supply of electricity, heat, gas and water |

| Beijing | 0.0000 | 0.0282 | 0.0510 | 0.0774 | 0.0000 | 0.0564 | 0.0600 | 0.0078 | 0.0224 | 0.0690 |

| Tianjin | 0.0281 | 0.0306 | 0.0466 | 0.0643 | 0.0411 | 0.0545 | 0.0488 | 0.0319 | 0.0567 | 0.0717 |

| Hebei | 0.0370 | 0.0421 | 0.0319 | 0.0538 | 0.0488 | 0.0443 | 0.0373 | 0.0401 | 0.0477 | 0.0525 |

| Shanxi | 0.0392 | 0.0449 | 0.0315 | 0.0479 | 0.0398 | 0.0448 | 0.0331 | 0.0402 | 0.0376 | 0.0303 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.0406 | 0.0466 | 0.0370 | 0.0578 | 0.0458 | 0.0454 | 0.0436 | 0.0378 | 0.0433 | 0.0128 |

| Liaoning | 0.0346 | 0.0412 | 0.0446 | 0.0549 | 0.0434 | 0.0437 | 0.0410 | 0.0399 | 0.0437 | 0.0474 |

| Jilin | 0.0351 | 0.0412 | 0.0474 | 0.0524 | 0.0291 | 0.0400 | 0.0424 | 0.0396 | 0.0333 | 0.0357 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.0357 | 0.0403 | 0.0471 | 0.0535 | 0.0441 | 0.0414 | 0.0384 | 0.0386 | 0.0363 | 0.0251 |

| Shanghai | 0.0238 | 0.0393 | 0.0682 | 0.0664 | 0.0224 | 0.0573 | 0.0604 | 0.0000 | 0.0222 | 0.0966 |

| Jiangsu | 0.0182 | 0.0207 | 0.0281 | 0.0121 | 0.0379 | 0.0526 | 0.0000 | 0.0424 | 0.0617 | 0.0845 |

| Zhejiang | 0.0160 | 0.0115 | 0.0464 | 0.0224 | 0.0522 | 0.0435 | 0.0317 | 0.0397 | 0.0547 | 0.0715 |

| Anhui | 0.0290 | 0.0350 | 0.0286 | 0.0434 | 0.0421 | 0.0363 | 0.0409 | 0.0417 | 0.0520 | 0.0645 |

| Fujian | 0.0261 | 0.0360 | 0.0425 | 0.0000 | 0.0322 | 0.0305 | 0.0361 | 0.0427 | 0.0498 | 0.0601 |

| Jiangxi | 0.0317 | 0.0273 | 0.0357 | 0.0367 | 0.0484 | 0.0411 | 0.0339 | 0.0383 | 0.0467 | 0.0557 |

| Shandong | 0.0296 | 0.0369 | 0.0214 | 0.0501 | 0.0429 | 0.0479 | 0.0377 | 0.0432 | 0.0507 | 0.0557 |

| Henan | 0.0346 | 0.0432 | 0.0363 | 0.0429 | 0.0431 | 0.0454 | 0.0312 | 0.0420 | 0.0429 | 0.0521 |

| Hubei | 0.0303 | 0.0395 | 0.0297 | 0.0395 | 0.0326 | 0.0455 | 0.0308 | 0.0416 | 0.0484 | 0.0579 |

| Hunan | 0.0301 | 0.0342 | 0.0412 | 0.0338 | 0.0458 | 0.0425 | 0.0192 | 0.0396 | 0.0452 | 0.0531 |

| Guangdong | 0.0233 | 0.0000 | 0.0504 | 0.0546 | 0.0546 | 0.0501 | 0.0437 | 0.0416 | 0.0530 | 0.0691 |

| Guangxi | 0.0363 | 0.0415 | 0.0411 | 0.0409 | 0.0433 | 0.0391 | 0.0386 | 0.0384 | 0.0419 | 0.0491 |

| Hainan | 0.0396 | 0.0391 | 0.0376 | 0.0583 | 0.0319 | 0.0417 | 0.0476 | 0.0371 | 0.0000 | 0.0555 |

| Chongqing | 0.0305 | 0.0334 | 0.0473 | 0.0291 | 0.0412 | 0.0442 | 0.0400 | 0.0392 | 0.0524 | 0.0622 |

| Sichuan | 0.0332 | 0.0343 | 0.0449 | 0.0320 | 0.0421 | 0.0409 | 0.0374 | 0.0394 | 0.0467 | 0.0469 |

| Guizhou | 0.0355 | 0.0389 | 0.0375 | 0.0432 | 0.0371 | 0.0422 | 0.0403 | 0.0372 | 0.0420 | 0.0447 |

| Yunnan | 0.0369 | 0.0443 | 0.0349 | 0.0411 | 0.0328 | 0.0424 | 0.0292 | 0.0391 | 0.0409 | 0.0471 |

| Xizang | 0.0443 | 0.0492 | 0.0000 | 0.0533 | 0.0215 | 0.0000 | 0.0461 | 0.0419 | 0.0280 | 0.0000 |

| Shaanxi | 0.0334 | 0.0394 | 0.0284 | 0.0435 | 0.0069 | 0.0373 | 0.0377 | 0.0405 | 0.0382 | 0.0474 |

| Gansu | 0.0358 | 0.0444 | 0.0411 | 0.0447 | 0.0433 | 0.0388 | 0.0332 | 0.0390 | 0.0342 | 0.0227 |

| Qinghai | 0.0410 | 0.0475 | 0.0366 | 0.0551 | 0.0264 | 0.0327 | 0.0415 | 0.0409 | 0.0438 | 0.0354 |

| Ningxia | 0.0411 | 0.0507 | 0.0434 | 0.0595 | 0.0412 | 0.0445 | 0.0493 | 0.0455 | 0.0468 | 0.0176 |

| Xinjiang | 0.0389 | 0.0452 | 0.0444 | 0.0489 | 0.0474 | 0.0426 | 0.0391 | 0.0376 | 0.0282 | 0.0266 |

5. Main Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Main conclusions

| (i) | The overall level of urban infrastructure resilience in China is low. In general, urban infrastructure in coastal regions is more resilient, while that in western and northeastern regions are less resilient. The structure of urban infrastructure resilience varies greatly across provinces and municipalities: high-level balanced provinces and municipalities are mainly distributed in the eastern regions, i.e. Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and the Yangtze River Delta region; medium-level balanced provinces and municipalities are great in number and are widely distributed; low-level balanced provinces and municipalities are mainly distributed in the central and western regions; and single-dimension dominated provinces and municipalities are disperse in distribution. | ||||

| (ii) | From the perspective of pre-disaster prevention capacities, Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Ningxia, and Hebei scored higher, while Guizhou scored the lowest. In terms of disaster resistance capacity, Tianjin, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Ningxia, Zhejiang, and Shandong scored higher, while Yunnan, Guangxi, Gansu, Heilongjiang, and Xizang scored lower. In terms of post-disaster recovery capacity, Beijing, Xizang, Jiangsu, Fujian, Shaanxi, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Tianjin scored higher, while Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Guizhou, Hebei, and Guangxi scored lower. | ||||

| (iii) | From the perspective of criterion layer, the main obstacle factors to urban infrastructure resilience include the construction enterprise capacity and energy supply capacity. From the perspective of index layer, power supply capacity is the main factor restricting urban infrastructure resilience, followed by the proportion of fixed asset investment in the production and supply of electricity, gas and water. | ||||

5.2. Policy recommendations

First, the concept of “resilience” should be integrated throughout the entire process of urban planning, construction, and governance. In the context of uncertain events and risks facing cities, building resilient cities is the key to sustainable urban development. Infrastructure is the lifeline and material foundation for the survival and development of cities, and building a resilient urban infrastructure system is a key part of building resilient cities. Urban infrastructure resilience has rich connotations, including the robustness of infrastructure systems, pre-disaster prevention and resistance capacity, and post-disaster recovery capacity, which involves the planning, design, site selection and construction, as well as operation and maintenance of urban infrastructure systems. It is an inevitable requirement for improving urban infrastructure resilience to take solid steps to explore methods for infrastructure planning in resilient cities suitable for China’s national conditions, and to explore resilient infrastructure construction and governance modes.

Second, it is important to accurately understand the current situation of urban infrastructure and improve the supply capacity of urban infrastructure. System redundancy is an important feature of resilience. Stockpiling sufficient emergency equipment, facilities and materials, and formulating emergency deployment plans to respond to various emergencies can improve the ability to cope with disasters, and is an important way to improve the resilience of urban infrastructure. Therefore, the census of urban infrastructure allocation should be promoted to improve the resource adequacy and redundancy of infrastructure systems.

Third, it is necessary to reasonably increase the investment of resources in the field of infrastructure and to consolidate the synergy of factors for the security of resilient cities. According to the current construction situation of urban infrastructure systems, it is suggested to properly increase the capital investment and personnel deployment of infrastructure systems, improve the operation and maintenance capacity of water, electricity and sanitation, and improve the pre-disaster prevention and post-disaster recovery capacities. The energy system is the most sensitive component of an urban infrastructure system. It is recommended to pay attention to the resilience construction of the energy system in the subsequent planning and construction of urban infrastructure, and make up for the shortcomings of the resilient infrastructure system.

Fourth, urban infrastructure risk assessment and scenario simulation of extreme impact events should be strengthened to optimize the spatial layout of infrastructure systems. More efforts should be made to assess potential natural disasters in cities, conduct multi-scenario simulations of extreme rainfall, extreme high temperatures, geological disasters, and seismic disasters, and optimize the site selection and spatial layout of urban infrastructure systems according to local conditions.

Fifth, it is essential to adhere to the innovation-driven approach and to improve urban infrastructure resilience through technological innovations and improved management modes. Attention should be paid to the R&D and application of new technologies and methods in the field of urban infrastructure, and the physical resilience of urban infrastructure can be upgraded through the renewal and transformation of construction methods and technological means and the application of new materials. It is important to accelerate the construction of digital and smart infrastructure, strengthen the application of digital technology and information technology, promote the digital and intelligent transformation of traditional infrastructure systems, make full use of big data technology to improve cities’ emergency response capacities, apply digital and intelligent technologies to the infrastructure systems of smart cities, and continuously improve the performance and management level of urban infrastructure systems.

ORCID

ZHUANG Li  https://orcid.org/0001-3039-5002

https://orcid.org/0001-3039-5002

YU Zhonglei:  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9606-9747

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9606-9747

SUN Chang:  https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3930-8485

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3930-8485

HOU Xiaojing:  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1108-1827

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1108-1827