Sustainable and Resilient Capacity Expansion Planning for Chemical Processing Industry: A Bi-Objective Approach

Abstract

According to United Nations reports, the worldwide population is expected to reach around 9.6 billion by 2050. This forecast emphasizes the critical role of energy and raw materials that are needed to meet the tremendous demand for goods. Consequently, firms feel pressured to establish sustainable and resilient strategic plans to acquire new process technologies and expand their capacity on time. These decisions are made at the highest management level, supported by a set of capacity expansion portfolios, to improve their competitiveness, especially in capital-intensive industries such as chemical processing. This paper investigates the sustainable and resilient capacity expansion problem for such industries within a long-term horizon. The main objective is to develop a holistic capacity expansion planning framework that fits the chemical processing industries and can be used to generate resilient scenarios while enhancing their sustainability measures. To this end, a bi-objective mixed-integer programming model was developed to solve the sustainability–resilience–profitability dilemma. The results showed a controversial relationship between the profitability of capacity expansion investments and a company’s commitment to sustainability and resilience. Furthermore, capacity expansion decisions were shown to primarily depend on the importance assigned to maximize profit as a managerial choice. However, there is no clear trend in sustainability preferences based on the sustainability weighting choice.

1. Introduction

According to United Nations reports, the worldwide population is expected to reach around 9.6 billion by 2050 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2017). This forecasting emphasizes the critical role of energy and raw materials that should be used to satisfy the tremendous demand for goods. In reality, the extraction of raw materials continues, new mines are opened, and several chemical processing industries are growing and expanding. Indeed, studies projecting trends into the mid-century expect a global growth rate of around 3% to 2050. The growth rate in developed countries and regions (North America, Europe, Japan, and Australia) is expected to average 2–3% annually, lagging that of developing economies in South America, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa (4–8%) (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2017). Due to this genuine market competition, companies are racing to improve their performance and introduce more efficient management approaches using their available resources to satisfy the short-term objectives of clients. However, this might contradict their long-term commitment to sustainability and resilience.

Considering long-term perspectives, capacity planning supports the acquisition of new sustainable technologies and the introduction of new products (Chou et al., 2007). One can remark that those decisions tend to be taken at the highest management level. Nevertheless, they require substantial capital resources with long payout times (Paraskevopoulos et al., 1991). These decisions are often irreversible, and the invested assets have a low salvage value. Therefore, the main challenge for these companies is to find a trade-off between expanding capacity and incorporating sustainability concepts to meet increasing demand while meeting their long-term goals.

Building supply chain resilience is becoming necessary as supply chains become more complex, and disruptions often severely impact organizations (Hamdi et al., 2020). However, there is a lack of consensus in the literature on the definition of supply chain resilience (Tukamuhabwa et al., 2015). Ponis and Koronis (2012) define it as the ability to plan and design the supply chain network to anticipate unexpected disruption with a negative impact on supply chain performance and to adapt efficiently to disruptions. Thus, supply chain resilience is a managerial capability to reach a robust state of operations without prohibitively high operational costs. On the other hand, sustainable supply chains can be viewed through a triple-bottom-line perspective (Ahi and Searcy, 2015). With such a perspective, economics and environmental aspects play a predominant role. Social concerns have recently received increasing attention (Hallinger, 2020), especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Sarkis, 2021). From an operational perspective, supply chain sustainability can be considered a risk management process where all sustainability-related risks are identified, assessed, and mitigated (Giannakis and Papadopoulos, 2016).

Chemical processing industries are typical capital-intensive industries in which strategic planning must coordinate capacity expansion and production decisions with sustainability and resilience (Barbosa-Póvoa, 2014). The goal is to balance their capital investments in utility maximization and performance effectiveness with environmental constraints. From this perspective, these industries invest heavily in more robust planning tools considering environmental regulations and market fluctuations (Al-Sharrah et al., 2001; Kallrath, 2005; Hahn and Brandenburg, 2018). Recent literature highlighted the criticality of this challenge. It emphasized the value of developing effective strategies for capacity expansion in capital-intensive industries such as oil and gas and chemical processing (MirHassani and Noori, 2011; Sahebi et al., 2014). However, based on the reviewed literature, minimal efforts are taken to incorporate sustainability and resilience in their capacity expansion decisions. This paper attempts to contribute to this research gap. The aim is to build a strong foundation for considering the following research questions:

| • | RQ1: How to incorporate sustainability-related supply chain risks and resilience factors in capacity expansion decisions for chemical processing industries? | ||||

| • | RQ2: How to formulate and validate a mathematical model to generate sustainable–resilient capacity expansion alternatives for chemical processing industries? | ||||

This paper investigates such challenges in capital-intensive industries and contributes to the existing literature in developing optimized strategies for capacity expansion planning. To this end, a sustainable and resilient capacity expansion planning framework is proposed, and a bi-objective Mixed Integer Programming (MIP) model is developed. The model covers the main requirements of the chemical processes while considering the essential resilience and sustainability constraints and objectives. The ultimate goal is to develop a holistic approach to generate capacity expansion scenarios that consider resilience and sustainability. An experimental study in the fertilizer processing industry illustrates the model structure and functionality.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sec. 2 summarizes the related literature. Sections 3 and 4 present the problem statement and the capacity expansion planning framework, respectively. Section 5 summarizes the experiments, analyzes the results, and highlights the resulting managerial insights. The last section presents conclusions, limitations, and perspectives for future research.

2. Related Works

In many industries, investing in capacity expansion remains one of the most critical decisions in strategic planning. Therefore, several works have investigated how to determine future expansion times, sizes, and locations for power generation (Murphy and Smeers, 2005), production planning (Chou et al., 2007), and urban infrastructure (Liu et al., 2020). Historically, capacity expansion problems have been introduced since 1982.

Luss (1982) proposed reviewing capacity expansion methods that emphasize modeling approaches and algorithmic solutions. However, the study was limited to a few applications. In fact, Martínez-Costa et al. (2014) focused on strategic capacity planning in manufacturing. They indicated that decisions such as resource allocations or production planning are widely considered in the literature. More recently, Chien et al. (2018) proposed an uncertain multi-objective decision strategy framework based on uncertainty theory for capacity expansion for smart production. The objective was to minimize the loss of capacity costs due to shortages, surpluses, and migration.

Understanding and building supply chain resilience is increasingly becoming necessary as supply chains become more complex. As indicated by Hamdi et al. (2020), supply chain disruptions often have a severe impact on organizations. Similarly, decisions about new product development or seasonality and their impact on inventories should be integrated into capacity expansion planning to ensure supply chain resilience. Therefore, investigating and understanding the factors contributing to building resilience will enable organizations to be better prepared for disruptive events (Khan et al., 2021). However, few researchers have considered supply chain resilience in capacity planning decisions. Christopher and Peck (2004) as well as Pettit et al. (2013) have examined several capabilities that are instrumental in building supply chain resilience. However, the interplay between sustainability practices implemented by a firm and its resilience is still unclear.

In line with extant literature (Sheffi and Rice Jr., 2005; Kochan and Nowicki, 2018), supply chain resilience is formed by two closely related dimensions: agility and robustness. As a proactive approach, robustness refers to the firm’s ability to keep operations running to withstand disruptive events (Kitano, 2004). On the other hand, as a reactive approach, “Agility” refers to the speed at which a firm will react to disruptive events and return to a normal situation (Wieland and Wallenburg, 2012; Chowdhury and Quaddus, 2017). The impacts of these two dimensions can be observed in the supply chains of capital-intensive industries such as oil and gas, power generation, and chemical processing. Furthermore, Chowdhury and Quaddus (2017) introduced a conceptual framework for managing resilience and increasing sustainability in the supply chain by integrating fundamental elements for analyzing, measuring, and managing resilience. A more specific study focused on the medical devices industry was conducted by Nayeri et al. (2022), who proposed a multi-objective mathematical model that considers sustainability, resiliency, and responsiveness to minimize environmental impacts and total costs while maximizing social impacts. In a study on Sustainable Food Supply Chain Planning Model, Das (2019) explored the integration of lean, green, and resilience criteria to create scopes for funding agencies to study “what-if” scenarios for supporting cooperative development. Recently, Pereira Grudzien et al. (2023) investigated major Industry 4.0 digital technologies that support sustainable strategic operations and proposed a model that highlights the need for a change in the perspective of process technology as a support area that enhances other functional areas.

In fact, capital-intensive industries have attracted much attention from researchers. Mitra et al. (2014) proposed a capacity planning and operation model for continuous power-intensive processes under time-sensitive electricity prices. They applied a proposed modeling framework to a cryogenic air separation plant (that produces liquid argon, oxygen, and nitrogen), where electricity costs represent a considerable percentage of production costs. Thomas and Bollapragada (2010) presented a decision support tool with an embedded mathematical model to support capacity planning decisions in the General Electrics solar industry, focusing on manufacturing photovoltaic cells to generate energy. From the same perspective, Cho et al. (2022) conducted a more comprehensive review of recent advances and challenges in optimization models for the expansion planning of power systems.

Few scholars were interested in mining and related chemical processing industries [see Leal Gomes Leite et al. (2020)]. We can cite Busnach et al. (1985), who examined capacity planning in mining from a strategic perspective and developed an integer programming model using a heuristic algorithm to maximize the NPV for a phosphate mining plant. Recently, Leal Gomes Leite et al. (2020) aimed to present a bibliographical review of mathematical modeling quantitatively related to all stages in the supply chain of the mining industry, and they investigated how current issues, such as environmental concerns and new technologies, have changed mining supply chain models. Future models will focus on environmental issues as very strong constraints. Furthermore, they noted that deterministic (65.2%) models are more predominant than stochastic (34.8%). Therefore, future work should focus on the stochastic aspect of the input data.

Therefore, one can conclude that strategic capacity expansion planning under resilience, sustainability, and market fluctuation has yet to be well investigated, especially for the chemical processing industries. Therefore, this paper contributes to this research gap and explores the challenge of capacity expansion in chemical processing. It presents a capacity expansion planning framework inspired by the fertilizer industry. The framework is illustrated by developing and solving a bi-objective MIP model that searches for a trade-off between maximizing earnings/profitability (say, Earnings Before Interest and Tax or EBIT) and choosing more resilient and sustainable expansion alternatives.

3. Problem Statement

The problem is formulated for the strategic capacity planning within the fertilizer companies’ internal supply chains over a 10-year horizon. The objective is to maximize EBITs in various investment scenarios while ensuring resilience and guaranteeing sustainability. The AIChE Sustainability Index is a practical tool for benchmarking the chemical industry (Cobb et al., 2007). It is used to assess the sustainability performance of chemical companies using publicly available data or projections. This index captures several drivers, such as strategic commitment, sustainability innovation, environmental performance, safety performance, social responsibility, and many more (Cobb et al., 2009). In this paper, the index is used to evaluate supplier/contractor selection for sourcing and capacity expansion. A fertilizer internal supply chain can be considered a combination of two sub-configurations: upstream, which consists of ore extraction, its beneficiation, and its transportation through a hybrid transportation system that uses trains and pipelines. The latter represents the downstream, related to the chemical transformation for sulfuric, phosphoric acids, and fertilizers production. Strategic capacity investment decisions can deal with downstream- and upstream-related assets. Consequently, the problem is formulated to answer the following three main questions. Strategic capacity investment decisions can deal with downstream and upstream-related assets. However, this work is limited to downstream-related assets. Thus, the problem is formulated to answer the following three main questions:

| • | How can decision-makers determine the optimal capacity expansion for their chemical processing plant to capture predicted future demand, and how can the model help in selecting the most sustainable contractor for this expansion? At what time should the expanded capacity be available to capture predicted future demand for the company’s chemical processes, and how can the proposed mathematical model assist in determining the optimal timing for this expansion? | ||||

| • | Is it preferable to invest in upgrading the chemical transformation assets? If yes, how to select them according to sustainability performances? | ||||

| • | What would be the most resilient supplier for our raw material purchasing strategy? | ||||

The herein decision-making problem can be structured as follows. First, we present the problem inputs:

| (1) | Forecast sales of fertilizers and phosphoric acids over 10 years. | ||||

| (2) | Production facilities capital and operating costs of the production facilities of fertilizers and acids. | ||||

| (3) | Raw materials costs. | ||||

| (4) | Current production process capacity of fertilizers and acids. | ||||

| (5) | Ongoing capacity expansion projects to upgrade the current supply chain. | ||||

| (6) | Consumption ratio for the raw materials depends on the facility and the final product. | ||||

The key requirement is to improve the company’s profitability along with the company’s sustainable brand equity. The main assumption is that a fertilizer company would invest and capture a market share if there is a chance of profitability and not because a quota is already established. The stochastic aspect of the problem is related to price, demand, supplier/contractor sustainability, and resilience engagement. In our study, we developed a holistic disruption index that encompasses the proposed price volatility (price fixed by the supplier itself), its capability of ensuring traceability and secure transportation, and reliability as a quality dimension. These variations were incorporated into the input generation engine in the proposed framework in Sec. 4. It is assumed that the company is not an industry leader (e.g. the market price of the product is independent of the company’s actions according to the Stackelberg–Nash–Cournot theory). The problem is formulated as a bi-objective MIP model to capture the key aspects of the overall supply chain and its complexity.

4. Capacity Expansion Planning Framework

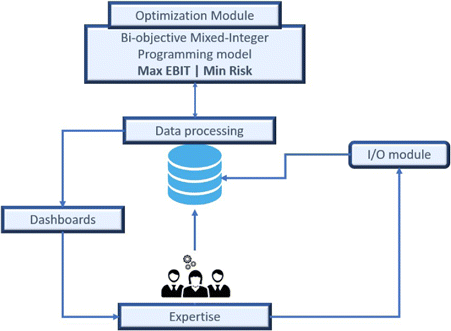

The proposed framework is presented in Fig. 1. The framework is entitled “CAPExp”. In the I/O and data processing modules, we prepare the required data for the optimization module. It uses a preliminary analysis to generate the sales prices of fertilizers and their by-products and raw materials according to a defined probability distribution and based on market expertise. Basically, this module uses a set of basic statistical patterns to guarantee the most accurate results. In addition, the same module prepares deterministic parameters in a proper format, such as the current process capacity and the consumption ratios of the raw materials necessary for each final product.

Fig. 1. CAPExp framework.

CAPExp embeds an optimization engine based on a bi-objective MIP. It maximizes EBIT. The positive cash flows (revenues) are the total sales revenue of the final products and the by-products. The negative cash flows (costs) are the current assets’ total fixed and operating costs of the current assets and the capacity expansions, including the sourcing of raw materials. It also minimizes the risk of purchasing raw materials from lower-tier suppliers or subcontracting expansion projects to low-tier contractors by maximizing sustainability performances (higher AIChE sustainability indices). The proposed mathematical model considers chemical processes and storage capacities. It ensures that the volume of fertilizers and the various acids produced by each chemical plant should not exceed its maximum actual capacity. The model also guarantees the expected sales and states the inventory balance. The proposed model sets a limit on the additional capacities according to an investment limit. The bottleneck chemical process in all entities should be identified in addition to the additional storage capacity limit. Nevertheless, the model considers all chemical entities’ internal consumption of intermediate acids, such as sulfuric acid, used for fertilizers production. The CAPExp framework can also visualize scenarios through dashboards that show capacity expansion over time versus demand evolution.

4.1. The bi-objective optimization model

This section first presents the sets, parameters, and decision variables used in the mathematical MIP model (refer to Tables 1–4). A detailed rich formulation is then presented considering the plant requirements that are essential to operate a sustainable and resilient capacity expansion plan at maximum profitability while attaining higher sustainability metrics.

| Set | Definition |

|---|---|

| t∈H | Set of time periods |

| f∈F | Set of fertilizers |

| c∈A | Set of sulfuric and phosphoric acids |

| X=A∪F | Set of all products |

| e∈Ep | Set of chemical plants processing product p∈X |

| a∈Pep | Set of chemical processes used to transform p in chemical plant e |

| r∈Rp | Set of raw materials (with intermediates) required to produce p |

| m∈Mep | Set of products for which p is a raw material or a sub-product used by chemical plant e |

| m′∈Emr | Set of chemical plants producing raw material r |

| k∈Ka | Set of contractors specialized in process a expansion |

| s∈Sr | Set of suppliers of raw material r |

| Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

| sp,t | Expected sales, in tons, for a product p at a time period t |

| pp,t | Forecast price for a product p at a time period t — USD/t |

| ca,p,e,0 | Current process capacity a used to transform p in chemical plant e at time t=0 |

| c+a,p,e,t | Additional process capacity already planned for a process a in chemical plant e at time t |

| αr,p,e,t | Consumption ratio for raw material r to produce p in chemical plant e at time t |

| βt | Acceptable disruption risk level at time period t |

| xp,p′,e=1 | If a product p is used to produce p′∈X in chemical plant e |

| zp=1 | Set of chemical processes used to transform p∈X within chemical plant e∈Ep |

| ρa,k,t | Estimated AIChE sustainability index of contractor k selected to expand process a at time t |

| ηr,s,t | Estimated AIChE sustainability index of supplier s selected for raw material r purchasing at time t |

| zp=1 | If a product p∈X is used as an intermediate product |

| rs,t=1 | Risk of disruption associated with supplier s at time period t |

| maxa,p,t | Maximum additional capacity expansion allowed for a process a used to produce a product p at time period t |

| Cost | Definition |

|---|---|

| CPXa,k,t | Capital expenditure spent at time period t for acquiring one unit of a chemical process a from a contractor k (USD/unit) |

| OPXp,e,t | Operating expenditure related to a product p transformed by a chemical plant at time period t (USD/plant/t) |

| Crs,t | Cost of raw material r purchased from supplier s at time period t (USD/t) |

| Decision variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Yp,e,t=1 | If product p is produced by chemical plant e at time period t |

| Zp,e,t=1 | If the storage capacity used for product p is in chemical plant e was expanded and ready to use at time period t |

| Xa,p,e,k,t=1 | If the capacity of process a, in chemical plant e, used to produce p was expanded and ready to use at time period t by contractor k |

| Wr,s,t=1 | If supplier s is selected to purchase raw material r at time period t |

| A+a,p,e,t≥0 | Additional capacity for chemical process a, used to produce p, in a chemical plant e, at time period t |

| CPa,p,e,t≥0 | Total capacity of chemical process a used to produce p in a chemical plant e at time period t |

| CTp,e,t≥0 | Total capacity of chemical plant e to produce p at time period t |

| Tp,e,t≥0 | Total volume of fertilizer and/or acid p∈X sold by chemical plant e at time period t |

| Qp,e,t≥0 | Quantity of fertilizer and/or acid p∈X produced by chemical plant e at time period t |

| Qrmr,s,p,e,t≥0 | Quantity of raw material r, purchased from a supplier s, used to produce a product p in a chemical plant e at time period t |

| Rp,e,t≥0 | Residual quantity of a product p produced by chemical plant e at time period t |

| I+p,e,t≥0 | Additional storage capacity needed for product p produced by chemical plant e at time period t |

| Ip,e,t≥0 | Storage capacity for product p∈X in chemical plant e at time t |

4.1.1. Objective functions

The first objective function (1) aims to maximize EBIT. This is obtained by subtracting total costs from total revenue. To maximize this term, costs must be decreased, or revenues must be increased. Chemical plants that contribute to the total revenue from the sale of fertilizers and phosphoric acids include ∑p∈X∑t∈Hpp,tTp,t. Forecast prices pp,t are generated based on historical data and market analysis. In addition, fixed costs are expressed for expanding the capacity of the process. If a process is expanded in a candidate plant, there will be fixed costs and capital expenditures for that particular process. Also, ∑p∈X∑e∈Ep∑t∈HOPXp,e,tQp,e,t calculates all production, storage, and labor costs. In addition, sourcing raw materials is an additional cost for a company. Thus, ∑p∈X∑e∈Ep∑r∈Rep∑s∈Sr∑t∈HCrs,tQrmr,s,p,e,t calculates all purchase costs from a set of pre-defined suppliers.

4.1.2. Fertilizer-related constraints

Constraints (3) impose that a set of chemical plants might meet the expected sales for a given fertilizer.

4.1.3. Acid-related constraints

Constraints (13) ensure that the amount of a specific acid produced by the plant does not exceed its capacity.

4.1.4. Supplier and contractor constraints

Constraints (24) and (25) indicate that only one contractor is chosen for a certain process capacity expansion at a certain time period. Additionally, only one supplier is selected from whom a raw material is purchased.

5. Numerical Study

This section tests the adequacy and applicability of the developed mathematical model in an industrial-size setting. First, the setup used to test and evaluate the proposed model is presented. Then, the performance of the proposed MIP is assessed using a set of random instances. A what-if scenario analysis is also conducted to check model sensitivity to expected changes. Based on the results obtained, several managerial insights are highlighted, followed by the limitations of the CAPExp framework.

All tests were conducted on an Intel Core i7 2600CPU (2.8GHz) and 16GB RAM. Python API of GUROBI 10.0.0 was used to solve the MIP model.

5.1. Test problems generation

The formulation and resolution of the defined problem as a bi-objective optimization problem require data sets that are not commonly used as benchmarks from previous studies. Thus, a set of instances was randomly generated to simulate realistic scenarios in practice. These instances are inspired by the internal supply chain of a fertilizer company. Furthermore, the proposed framework is designed and implemented to adapt to real-setting data instantly. The planning horizon, in all instances, covers a period of 10 years with a time step of 1 year.

Table 5 presents the main chemical products produced by a given fertilizer company. Four types of fertilizers (MAP, DAP, TSP, and NPK) were considered. All of them are made by reacting with different acids and minerals, such as phosphoric acid (PAC28) and phosphate rocks. In fact, phosphoric acid is considered an intermediate product used to produce fertilizers and a final product after its concentration. A fertilizer company must import raw materials such as phosphate rocks and liquid sulfur to transform them internally into sulfuric acids, ammonia, and other additives needed for the fertilizers’ production process. For this case study, different providers can supply each raw material according to a specific purchasing cost generated by a log-normal distribution. The amount required for these raw materials depends on various consumption ratios, as shown in Table 6.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Fertilizers | |

| MAP | Mono-ammonium phosphate, which is a water-soluble fertilizer |

| DAP | Di-ammonium phosphate, which is a fertilizer containing nitrogen and phosphorus |

| TSP | Triple Super Phosphate, which is a white, granular, or crystalline fertilizer, highly soluble in water |

| NPK | A fertilizer composed of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium |

| Acids | |

| PAC54 | Concentrated phosphoric acid |

| PAC28 | Non-concentrated phosphoric acid |

| SAC | Sulfuric acid |

| Code | Raw materials/intermediate acids | Consumption rqmts. |

|---|---|---|

| MAP | PAC 28 | 0.5335 |

| Ammonia | 0.1387 | |

| NPK | PAC 28 | 0.2198 |

| Ammonia | 0.1620 | |

| Potassium chloride | 0.2672 | |

| Boric acid | 0.0183 | |

| Zinc oxide | 0.0064 | |

| DAP | PAC 28 | 0.4749 |

| Ammonia | 0.2261 | |

| SAC | Liquid sulfur | 0.3269 |

| PAC28/54 | Phosphate | 3.5684 |

| SAC | 3.0309 |

The production of fertilizers, phosphoric acid, and sulfuric acid follows a sequence of chemical reaction processes. Tables 7 and 8 highlight the main chemical processes involved in the major fertilizer production, as well as acids. These processes have initial plant-related capacities. In this study, the internal supply chain is designed as a network of six chemical plants capable of producing a mix of fertilizers and acids, as shown in Tables 7 and 8.

| Chemical plant | Chemical process | Capacity | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant 1 | Scrubbing-mixing | 4.465 | MAP, DAP, NPK |

| Granulating | 4.465 | MAP, DAP, NPK | |

| Drying | 4.465 | MAP, DAP, NPK | |

| Refining | 5.465 | NPK | |

| Plant 2 | Scrubbing-mixing | 4.169 | MAP, DAP |

| Granulating | 4.152 | MAP, DAP | |

| Drying | 4.152 | MAP, DAP | |

| Plant 4 | Scrubbing-mixing | 3.685 | TSP |

| Granulating | 3.695 | TSP | |

| Drying | 3.685 | TSP | |

| Plant 5 | Scrubbing-mixing | 4.822 | NPK, TSP |

| Granulating | 4.822 | NPK, TSP | |

| Drying | 4.822 | NPK, TSP | |

| Refining | 4.822 | NPK, TSP |

| Chemical plant | Chemical process | Capacity | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant 1 | Combustion | 1.05 | SAC |

| Conversion | 1.05 | SAC | |

| Condensation | 1.05 | SAC | |

| Reaction | 1.05 | PAC28 | |

| Separation | 1.05 | PAC28 | |

| Filtration | 1.05 | PAC28 | |

| Concentration | 0.5 | PAC54 | |

| Plant 2 | Combustion | 0.984 | SAC |

| Conversion | 0.984 | SAC | |

| Condensation | 0.984 | SAC | |

| Reaction | 0.984 | PAC28 | |

| Separation | 0.984 | PAC28 | |

| Filtration | 0.984 | PAC28 | |

| Plant 3 | Combustion | 1.695 | SAC |

| Conversion | 1.625 | SAC | |

| Condensation | 2.698 | SAC | |

| Reaction | 2.698 | PAC28 | |

| Separation | 2.698 | PAC28 | |

| Filtration | 2.698 | PAC28 | |

| Concentration | 1.000 | PAC54 | |

| Plant 4 | Combustion | 1.365 | SAC |

| Conversion | 1.635 | SAC | |

| Condensation | 1.258 | SAC | |

| Reaction | 1.258 | PAC28 | |

| Separation | 1.258 | PAC28 | |

| Filtration | 1.258 | PAC28 | |

| Concentration | 1.252 | PAC54 | |

| Plant 5 | Combustion | 0.546 | SAC |

| Conversion | 0.546 | SAC | |

| Condensation | 0.546 | SAC | |

| Reaction | 0.546 | PAC28 | |

| Separation | 0.546 | PAC28 | |

| Filtration | 0.546 | PAC28 | |

| Plant 6 | Combustion | 1.000 | SAC |

| Conversion | 1.000 | SAC | |

| Condensation | 1.000 | SAC | |

| Reaction | 1.000 | PAC28 | |

| Separation | 1.000 | PAC28 | |

| Filtration | 1.000 | PAC28 | |

| Concentration | 1.000 | PAC54 |

Fertilizer demand planning involves forecasting future needs based on population growth, crop yields, and weather patterns. Farmers, manufacturers, and governmental agencies must make informed decisions about fertilizer production and distribution decisions. However, annual demand and selling prices were generated using a log-normal distribution to produce stochastic instances for testing. Table 9 summarizes how demand forecast was generated for fertilizers and acids over a 10 years horizon.

| Code | Annual demand | μl | σl | Price | μl | σl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP | Log-normal random | 7.90 | 0.23 | Log-normal random | 5.56 | 0.44 |

| DAP | Log-normal random | 7.12 | 0.36 | Log-normal random | 5.22 | 0.21 |

| TSP | Log-normal random | 6.83 | 0.19 | Log-normal random | 5.99 | 0.15 |

| NPK | Log-normal random | 6.89 | 0.15 | Log-normal random | 5.69 | 0.43 |

| PAC54 | Log-normal random | 7.63 | 0.23 | Log-normal random | 4.25 | 0.55 |

CAPEX (USD per process expansion) is often associated with expanding existing chemical processes or constructing new facilities. It requires a significant capital investment to purchase equipment, build structures, and upgrade existing infrastructure. Furthermore, the cost of the expansion depends on factors such as the size and complexity of the expansion, the location of the facility, and the technology used. We select the log-normal distribution with μl ∼ [11.37, 13.11] and σl ∼ [0.09, 0.13] to capture this annual variability per contractor. The estimated parameters are based on an extensive benchmark.

OPEX (USD/t) for a phosphoric acid or fertilizer plant may vary significantly depending on capacity, location, and technology. Generally, energy costs make up most of the OPEX for these plants. Other costs, such as labor, maintenance, and environmental compliance, can also be significant. We select the log-normal distribution with μl ∼ [3.88, 4.98] and σl ∼ [0.12, 0.25] to capture this yearly variability per plant and product. The estimated parameters are based on an extensive benchmark.

AIChE sustainability index can be used to predict the future sustainability performance of the fertilizer industry by identifying trends and areas where improvement is needed. The index can also be used to compare the sustainability performance of different companies within the industry, providing valuable information for investors, policymakers, and consumers. As shown in Table 10, random values were generated between 20 and 60 as a sustainability assessment for the suppliers and contractors. In addition, the risk of disruption associated with a supplier is chosen randomly between 0.30 and 0.70. On the other hand, an acceptable level of disruption risk is randomly chosen between 0.45 and 0.99.

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| rs,t | U [0.30, 0.70] |

| βt | U [0.45, 0.99] |

| maxa,p,t | U [800,000; 2,500,000] |

| ηr,s,t | U [20, 60] |

| ρa,k,t | U [20, 60] |

It is clear from the model formulation in the previous section that some data to use in the model is sometimes difficult to find. The company should try to collect many input parameters to use the proposed model. However, the primary goal of this paper is to demonstrate how the mathematical model can be used to evaluate the impact of sustainability and resilience engagement on capacity expansion decisions, especially for capital-intensive industries. The model could be modified to capture specific industry strategic considerations and populated with additional data.

5.2. Summary of results

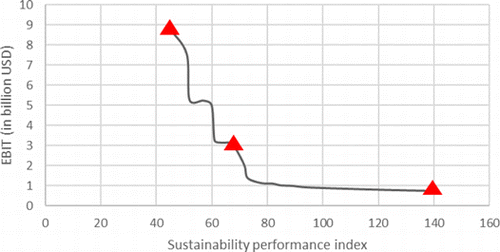

This section evaluates the performance of the GUROBI 10.0.0 MIP solver used to solve the proposed MIP model. The time limit for GUROBI 10.0.0 MIP solver was set to 3600s, while the tolerance for the integer solution was set to 1%. To make the resulting Pareto analysis more sensitive and dynamic, the proposed model was run 50 times with different weight parameters. This approach allowed for the exploration of a wide range of trade-offs between sustainability, resilience, and profitability, leading to a more robust understanding of the problem and its potential solutions. The resulting Pareto frontier is presented in Fig. 2, which summarizes the different scenarios generated by varying the weight parameters in the bi-objective model. All results were stored in a single database for further analysis. By plotting the results for each objective on the x and y axes, the Pareto frontier provides a better explanation.

Fig. 2. Pareto front for 50 runs.

All runs for the Pareto analysis could be solved within an acceptable time of approx. 1021s. On average, the time elapsed to find a feasible solution for the proposed MIP was rather short, at 150s.

Trying to keep the risk of raw materials disruption as low as possible and a strong sustainability engagement by suppliers and contractors, the overall capacity, on average, was increased by only 15% with an average EBIT of USD 0.729B. Supplier selection had a restrictive impact on capturing increasing market demand. However, the resulting capacity expansion plan was conservative. However, changing the weight to maximize EBIT increases the risk of disruption and sustainability involvement. On average, the selected contractors and suppliers had less than 45 in total, while the company invested heavily in expanding its capacity to reach an average EBIT of USD 8.729B. In fact, the general capacity expansion reaches 35%.

Based on the resulting Pareto analysis, one can remark that capacity expansion investments depend on the importance of maximizing profit. However, there is not a clear trend depending on the sustainability weighting.

5.3. What-if scenario analysis

Multiple what-if analyses can be performed to generate managerial insight into the problem of interest. The focus was on the following three major cases: (1) Profitability first is the highest point on the Pareto front. In the first scenario, we assume that the company places a higher priority on maximizing its financial performance and has limited engagement with sustainability practices. Consequently, the company may not have a robust system in place to ensure supplier and contractor selection aligns with sustainability goals and may not have invested in resilience measures to mitigate potential disruptions to their operations. Therefore, the primary objective of the company is to maximize its EBITs. (2) Sustainability–resilience–profitability balance. In the second case, the company is attempting to strike a balance between sustainability, resilience, and profitability. While they have taken some steps towards becoming a more sustainable company, they also prioritize maintaining their market share. This presents a dilemma where the company must compromise between its sustainability goals and its profitability goals in order to maintain its competitive position in the market. (3) Sustainability first. The third case of “sustainability first” represents a scenario where the company prioritizes sustainability above all else, including profitability. This case is considered a utopian situation because, in reality, it is very rare for a company to place sustainability ahead of financial gain.

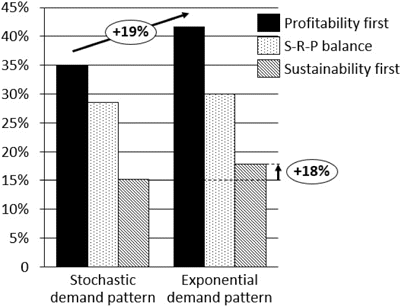

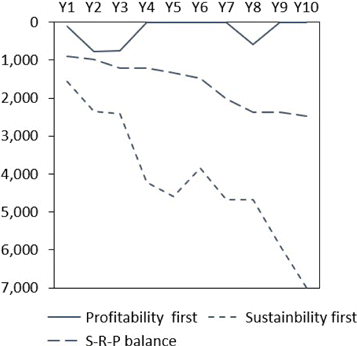

According to Fig. 3, when companies favor profitability over sustainability and resilience, they invest heavily in capacity expansion to capture future demand. Furthermore, this trend is more notable when demand increases exponentially. As you remark, investments in capacity expansion increased by 19% compared to an undetermined demand pattern. However, when a company searches for a compromise on the sustainability, resilience, and profitability dilemma, it directly impacts its capacity expansion investments. Additionally, this impact is more significant when the company is fully engaged in improving its sustainability performance. These managerial decisions significantly vary a company’s ability to capture future demand growth. As you can observe in Fig. 4, the complete favor of sustainability over profitability limits capacity expansions and then losses of market shares (unsatisfied demand reaches 5.6M tons of equivalent DAP on average), making companies race to find a balance between sustainability, resilience, and profitability, even though it could cost a relative loss (1.4M tons on average). Also, selecting suppliers with weak resiliency, such as those with a high risk of disruption, can have a substantial impact on a company’s operations. Based on our preliminary results, even a small increase in supplier disruption risks, such as a 2% increase across all suppliers, can lead to a significant decrease in profitability, with a reduction of 1.34%. This highlights the importance of considering supplier resilience when making sourcing decisions to mitigate potential disruptions and protect the company’s financial performance.

Fig. 3. Capacity expansion (in %) compared to the current situation.

Fig. 4. Unsatisfied demand for fertilizers (in kt) over the planning horizon.

Note that the bi-objective optimization model used in this study considers sustainability and financial profitability as optimization criteria and resiliency as a constraint. This means that the model takes into account not only the financial aspects of the company’s decision-making but also the environmental and social impacts of its operations. Additionally, the analysis of the three major cases presented in the study explicitly includes a scenario where sustainability is given the highest priority, highlighting the significance of sustainable practices in the decision-making process. The findings of the study also suggest that companies need to strike a balance between profitability, sustainability, and resilience to capture future demand growth while minimizing losses. Based on our findings, sustainability integration in the decision-making process has a significant impact but also emphasizes the importance of sustainable practices in achieving long-term success for companies.

5.4. Theoretical and managerial implications

The interest in studying this problem has resulted in both practical and theoretical implications. Theoretically, a new mathematical formulation for sustainable and resilient capacity expansion planning for the chemical processing industry. This was integrated into a holistic strategic planning framework. This contributes to existing literature (Martínez-Costa et al., 2014) and addresses the research gap of incorporating sustainability and resilience in strategic capacity expansion. Better still, multiple managerial insights can be learned from the studied problem. Major practical implications include the following:

| • | Implementing the proposed framework implies high involvement of the top management to ensure the accuracy of the input data. In fact, the computational results of the model are promising. However, major tasks still need further investigation to improve the preparation of input data. The choice of a probability distribution is crucial to mimic future market behavior and price fluctuation. | ||||

| • | The proposed strategic planning framework increases decision-makers’ awareness of trade-offs between economic and sustainability objectives and provides information on costs associated with improving resilience performance. Planners can generate different capacity expansion plans and analyze their impact on profitability, resilience, and sustainability engagement. | ||||

| • | Managers should develop a common understanding of acceptable disruption risk as this factor impacts capacity expansion decisions and resulting profitability. The proposed framework cannot be used only as an alternative generator but also as an evaluation tool. Therefore, managers could use it to define a baseline to assess the risk of disruption. | ||||

| • | Selecting a sustainably compliant contractor to expand capacities might not guarantee sustainable day-to-day operations. Lean manufacturing and technology selection efforts should be made to achieve operational efficiency and target net zero through various measures such as reducing emissions, using renewable energy, carbon capture and storage, and afforestation. | ||||

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Perspectives

This paper has investigated the sustainability–resilience–profitability nexus in the chemical process industry. It has addressed the industry’s sustainable and resilient capacity expansion problem within a long-term horizon. The contribution of this paper is to design a holistic framework for sustainable and resilient capacity expansion planning for the chemical process industry. A bi-objective mathematical model was developed to generate optimal capacity expansion plans for a fertilizer company. Resilience was incorporated through supplier selection, while sustainability engagement was investigated using the AIChE assessment framework.

From a practical standpoint, our paper provides a comprehensive decision-making framework for top managers to optimize their capacity expansion planning decisions, taking into account multiple objectives and trade-offs. The mathematical model enables decision-makers to identify the optimal balance between sustainability, resilience, and profitability. By using this model, companies can make informed decisions that take into account the potential risks and trade-offs associated with selecting suppliers with varying levels of resiliency.

Academically, our study has several important contributions to the field of strategic capacity expansion planning. First, we demonstrate the value of considering multiple objectives in capacity expansion and supplier selection decisions, such as sustainability, resilience, and profitability. Second, we emphasize the significance of taking into account potential trade-offs between these objectives and the impact of disruption on financial performance. Third, we provide a robust optimization model that can address these challenges and produce Pareto-efficient solutions. Lastly, our study offers insights into the impact of supplier resiliency on financial performance and the sustainability–profitability nexus.

The findings, with respect to the weight of the studied objective function, showed a compromised way of dealing with the controversial relationship between capacity expansion investment’s profitability and a company’s engagement in terms of sustainability and resilience. The results depict a shifting of burdens between the individual performance indicators as the proposed framework could be used to find a trade-off. From this perspective, using a friendly user weighting method is recommended, providing efficient alternatives as decision-making foundations. Thus, this framework creates a guideline for top managers to determine an optimal balance between resilience, sustainability, and long-term profitability in their capacity expansion plans.

While there are valuable findings and insights to recover from investigating this challenge, it is mandatory to note its limitations with respect to some assumptions. One of the challenging limitations of this study is the prediction of the future sustainability engagement of a company and its resilience. In a less ethically competitive market, information about sustainability and resilience might be inaccurate or falsified. Furthermore, in practice, the choice of the AIChE sustainability index could not be adequate for a particular company. Thus, the proposed framework was developed to adapt to the company’s choice easily. In addition to this, the proposed model did not consider the impact of current and future utility capacities. In contrast, chemical process industries’ performances also depend on their ability to support production from an energy perspective. There are some interesting directions for future work. First, we propose investigating robust optimization or stochastic programming to handle input uncertainty. Also, one can investigate the vertical integration of strategic capacity expansion decisions with tactical and operational decisions, especially inventory management and control. Finally, it is suggested to consider discount rates and pricing in the proposed problem.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge financial support from Abu Dhabi University’s Office of Research and Sponsored Programs (Grant No. 19300779).