Challenges in Transitioning from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: A Multicriteria Analysis

Abstract

In this study, we evaluate the transition from Industry 4.0 (I4.0) to Industry 5.0 (I5.0) using a multicriteria approach that integrates the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Fuzzy Inference Systems (FISs). Key criteria identified through a comprehensive literature review include sustainability, human factors, resilience and organizational management, which are critical for the successful implementation of I5.0. AHP is utilized to rank these criteria and assign relative weights, reflecting their importance in the overall evaluation. FIS is employed to manage the inherent uncertainty and imprecision in decision-making within the context of I5.0. The results provide a holistic view of how companies navigate this transition, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses. This study offers valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with adopting I5.0, emphasizing the utility of combining multicriteria approaches for strategic decision-making in dynamic industrial environments. These findings aim to support organizations in making informed decisions, fostering a more innovative, sustainable and human-centric industry. The combination of these methodologies provides a robust foundation for future research and practical applications in advancing I5.0.

1. Introduction

The realm of Industry 4.0 (I4.0) has predominantly focused on the technical aspects of its implementation, relegating human skills to a secondary role in this industrial revolution. This lack of consideration for the human factor has faced significant criticism in its development. The literature has evidenced that I4.0 has dehumanized the industrial sector, concurrently leading to increased technological unemployment, environmental pollution and cybersecurity issues. These adverse effects are expected to intensify in the coming years as I4.0 development concludes. To address this scenario, the concept of Industry 5.0 (I5.0) emerges as a proposal aiming to rectify these emerging problems (Xu et al., 2021; Pizoń and Gola, 2023; Baig and Yadegaridehkordi, 2024), encouraging us to look beyond I4.0 and consider the advancements and future potential of I5.0 (Kumar et al., 2022).

I5.0 stands for the future of industrial change and offers potential solutions to socio-economic and ecological problems (Ghobakhloo et al., 2023). I5.0 represents the next evolution in the value chain of the manufacturing industry, grounded in the integration of digital technology and automation with a more human and sustainable perspective (Fukuda, 2020). This new form of production emphasizes collaboration between humans and machines, aiming to enhance efficiency, sustainability and quality of life. However, the adoption of I5.0 also poses challenges and risks such as technological complexity and the need for a fair and equitable transition for workers.

Numerous authors have emphasized that I5.0 is the natural/logical outcome of the development and evolution of I4.0 (Ozdemir and Hekim, 2018; Javaid and Haleem, 2020; Kumar et al., 2021). In contrast to previous industrial revolutions that directly started in the industry, I4.0 was propelled by technological advancements used by workers in manufacturing enterprises. Today, the refinement of these technologies and their connectivity contribute to the progress of the manufacturing sector and the overall development of society and business. In this context, I5.0 acknowledges the industry’s capacity to achieve social objectives beyond employment and growth, producing within the environmental limits of the planet and prioritizing the well-being of industry workers (Xu et al., 2021). Although I4.0 is not yet fully developed, many industry pioneers and technological leaders believe that I5.0 is a renewed industrial vision with broader scope and a focus on human factors.

According to the European Commission, I5.0 centers on worker well-being and complements I4.0 by fostering a more sustainable, human-centric and resilient industry. Resilience, in this context, refers to the ability to flexibly confront changes, given the increasing susceptibility of globalized value chains and markets to disruptive shifts caused by political transformations and natural emergencies. In this regard, the industry of the future must be equipped to swiftly adapt to changing circumstances in value chains to ensure its role as a sustainable driver of prosperity (Breque et al., 2021).

Successful implementation of I5.0 demands a robust and effective organizational strategy. This organizational strategy is pivotal for the effective adoption of I5.0, addressing barriers, leveraging facilitators, identifying new business models and driving innovation within the organization (Scuotto et al., 2017; Kohnová et al., 2019; Stentoft et al., 2019). In this context, the organizational strategy should focus on creating a sustainable competitive advantage. This involves an emphasis on differentiation and innovation, with I5.0 directing its efforts toward harnessing new technologies to create novel products and services that deliver value to customers through personalization and sustainability.

In this regard, the literature presents various studies that have examined these aspects. Studies such as Sindhwani et al. (2022) evaluated the relationship of I5.0 with resilience and social value creation. Through a multicriteria analysis, they identified that the personalization criterion carried the most weight, followed by human–machine collaboration, creating an intelligent cognitive environment for humans. The authors emphasize that human intelligence is employed in more critical areas, contributing to society’s focus on the development of social values. Similarly, through a multicriteria decision-making approach, Mukherjee et al. (2023) found that barriers associated with costs and financing systems, scalability of capacity, skill enhancement and retraining of the human workforce are perceived as the most prominent barriers. The authors provide detailed strategies to address the identified barriers.

Other publications delve into various aspects of I5.0, considering sustainability (Foresti et al., 2020; Carayannis et al., 2022), employability and the human factor (Breque et al., 2021; Grabowska et al., 2022). Javaid and Haleem (2020) presented an analysis of critical adoption points in I5.0. Studies on resilience and smart manufacturing are evident (Romero and Stahre, 2021), along with their impact on supply chains (Frederico, 2021). Other authors have discussed barriers and enablers of implementing emerging technologies in industrial development processes (Huang et al., 2019; Choudhary and Mishra, 2022; Mukherjee et al., 2023) and how to select the appropriate strategy for implementation (Erdogan et al., 2018).

Despite the achieved progress, manufacturing companies are under constant pressure to innovate and adopt digital and automated technologies. I5.0 emerges as an opportunity to enhance efficiency, productivity and sustainability in manufacturing. However, its adoption comes with significant challenges and risks, including technological complexity, the demand for new skills and competencies among workers, massive product and service personalization, and challenges related to sustainability and equity. In response to these challenges, there is a need to identify the best strategies for the effective implementation of I5.0 in companies by recognizing and measuring its challenges, aiming to maximize benefits while minimizing associated risks.

The literature review shows that although significant studies have been conducted on evaluating criteria in decision-making and implementing Industry 4.0 (Sevinc et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; Nimawat and Gidwani, 2021; Choudhary and Mishra, 2022; Agarwal and Ojha, 2024), there is a lack of strategic focus on how Industry 5.0 can be utilized and implemented (van Erp et al., 2024) and research results are relatively scarce (Leng et al., 2022). This deficit is more pronounced due to the absence of standardized evaluation frameworks that comprehensively cover key dimensions proposed by the European Union alongside those intrinsic to business strategy. With Industry 5.0 pushing the technological limits of Industry 4.0 and introducing new dimensions such as sustainability, human factors and resilience, the lack of widely accepted evaluation frameworks seriously impedes progress (Grabowska et al., 2022; Breque et al., 2021). Furthermore, given that Industry 5.0 is a nascent and evolving paradigm, the limited availability of standardized evaluation frameworks exacerbates this issue. This gap not only limits conclusive knowledge in the scientific literature but also prevents organizations from making informed and strategic decisions regarding Industry 5.0 adoption. Consequently, our study seeks to address this gap by designing an evaluation framework that integrates methodologies such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Fuzzy Inference System (FIS). This approach aims to empower organizations to make strategic decisions to effectively address the challenges posed by Industry 5.0.

The lack of a suitable approach that comprehensively addresses the evaluation and prioritization of these challenges can lead to inefficient implementation and operational issues in the adoption of I5.0. Therefore, it is crucial to develop an assessment framework that enables organizations to understand and effectively manage the diverse dimensions involved in the successful implementation of I5.0. In this context, both the AHP and FIS emerge as valuable tools for addressing the assessment of these dimensions. AHP allows for breaking down the problem into a hierarchical structure of criteria and sub-criteria, utilizing expert opinions to assign relative weights to each dimension. On the other hand, FIS enables the creation of a set of rules that facilitate understanding the behavior of a system through linguistic interpretations of inputs and outputs, facilitating both information input and result analysis (Shakouri and Tavassoli, 2012). Based on the literature review and background, the following research questions are posed:

| (a) | What criteria are suitable for evaluating the implementation dimensions of I5.0, considering factors such as the human factor, sustainability, resilience and organizational strategy? | ||||

| (b) | What are the outcomes of applying the proposed methodologies and criteria to assess the implementation dimensions of I5.0? | ||||

| (c) | How do these evaluations respond to adjustments in the criteria weights, and what implications does this have for decision-making in organizations transitioning to I5.0? | ||||

The significance of this study lies in the potential impact of the transition from I4.0 to I5.0, representing a new chapter in the technological and socio-economic evolution of the global industry. As we progress toward an era of total connectivity and autonomous systems, there is a need to understand and address the challenges accompanying this transition. A study focused on the transition to I5.0 is vital due to its significant implications for society, the economy and the business environment. These challenges include aspects proposed by the European community (human factor, sustainability, resilience) and organizational strategic aspects. Understanding and addressing these challenges will enable a more effective and beneficial transition to I5.0, driving innovation, competitiveness and sustainable development in the global industrial landscape.

In this regard, the main objective of this study is to develop a comprehensive assessment framework that integrates AHP and FIS to identify and prioritize critical implementation dimensions of I5.0. The aim is to provide organizations with a practical and robust tool for making informed and strategic decisions on their path to the successful adoption of I5.0, considering the complex and changing nature of this new industrial paradigm. This multicriteria analysis methodology involves the evaluation of multiple criteria for informed and sustainable decision-making. In this work, criteria related to the human factor, sustainability, resilience and organizational strategy will be evaluated. Recommendations for the effective implementation of I5.0 will be formulated based on this assessment.

This study is expected to yield results that contribute to understanding and addressing existing scientific gaps in the implementation of I5.0 in businesses. Additionally, by developing a specific assessment framework for I5.0, organizations will be provided with a robust and reliable tool to assess their readiness, identify areas for improvement and define effective implementation strategies. The results of this study are expected to be applicable in various business contexts and serve as a basis for future research and policy development in the field of I5.0. Ultimately, this study is expected to contribute to maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks and challenges associated with the adoption of I5.0, promoting the successful transformation of manufacturing companies into the next industrial era.

In this context, this paper first presents a comprehensive review of existing literature on I4.0 and I5.0, highlighting key differences and challenges associated with this transition. Next, the methodology used, focusing on AHP and FIS as tools for evaluating the implementation dimensions of I5.0, will be described. Subsequently, the results obtained through the application of these methodologies will be presented, emphasizing the identified key criteria and their relative weights. Finally, the practical implications of the findings will be discussed, and recommendations for the effective implementation of I5.0 in businesses will be offered.

2. Literature Review on I5.0

This section provides a literature review on I5.0, including definitions of dimensions derived from the review and theoretical information from research contributions made by this study. In the initial stage of the literature review, the identification and categorization of key dimensions for the implementation of I5.0 were conducted. The papers considered for this study were confined to the period from 2015, when the term I5.0 was introduced (Rada, 2017), to 2023. Following the stages proposed by Tranfield et al. (2003), for a systematic review approach, crucial themes were identified, the extent of the literature was assessed and thematic areas of interest were delineated.

Considering the concepts associated with I5.0 and in line with the guidelines of the European Commission, the keywords used in the search for appropriate articles included “Industry 5.0”, “Industry 4.0”, “Industrial Automation”, “Internet of Things in Industry”, “Smart Manufacturing”, “Industrial Digitalization”, “Industrial Sustainability”, “Society 5.0”. The search yielded 85 research papers and 12 conference papers. In addition to these results, other papers were individually examined and added during the selection process based on their background, reviews and identified citations. After filtering the documents and excluding those not relevant to the interests of this research, and removing duplicate articles from the search databases, the most relevant ones (60) were considered and individually studied to determine their significance for the present investigation. In this context, they were preselected and aligned for a final evaluation and for the selection of analysis criteria for I5.0.

2.1. The I5.0 concept

The literature review identified that the concept of I5.0 was introduced to develop advanced manufacturing techniques to meet highly individualized product needs, with a focus entirely centered on human beings to address diverse societal needs and potential challenges (Rada, 2017; Martynov et al., 2019; Fukuda, 2020; Majernik et al., 2022). Several studies confirm that one of its main drivers is the widespread introduction of the latest digital technologies (Martynov et al., 2019; Orlova, 2021). The application of these technologies has had a significant impact on efficiency, product/service life cycle and business models, enabling complete automation of the production process and ensuring greater human–machine interaction (Javaid and Haleem, 2020). In this regard, the main difference between I4.0 and I5.0 lies in their focus and objectives. I4.0 has guided production toward sustainable smart factories, where autonomous interaction between machines and products takes center stage (Gorkhali, 2022). This paradigm underscores the automation and digitization of manufacturing processes, leveraging technologies like IoT and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to attain efficient and personalized production. In contrast, I5.0 seeks collaboration between humans and machines, fostering interaction and cooperation to perform complex tasks, implying a greater integration of human skills and technological capabilities. Furthermore, I5.0 is oriented toward more sustainable, flexible and personalized production, addressing specific customer needs, and promoting the creation of customized products and services. Table 1 illustrates that the evolution from I4.0 to I5.0 signifies a fundamental shift away from solely automated manufacturing toward a more human-centered, customization and sustainable approach. This transition encompasses not only technological progress but also significant changes in organizational mindset and societal values.

| I4.0 | I5.0 |

|---|---|

| Automation of industry | Humanization of industry |

| Customization | Customization and empowerment of humans |

| Increase productivity | Sustainable development |

| Automation to reduce costs and minimize errors | Data analytics to predict any error |

| Smart manufacturing | Smart society |

| IoT, Cloud, Robots, 3D printing | IoE, edge computing, Cobots, 3D/4D printing, 5G, blockchain |

| Higher energy usage | Smart energy |

While I4.0 has been primarily concerned with establishing smart factories through the implementation of robotics and virtualization in production systems, I5.0 places a greater emphasis on the synergistic relationships between these systems and individuals. This concern extends to social, democratic and ethical considerations (Ozdemir and Hekim, 2018). Given that I4.0 has struggled to address and meet the growing demand for personalization, the term I5.0 was coined to address personalized manufacturing and empower humans in the production processes (Martynov et al., 2019; Javaid et al., 2020). I5.0 is thus an amalgamation of technological advancements from I4.0 and a highly skilled and creative workforce. It establishes a human-centered workplace dedicated to producing customized products meeting specific requirements for high value and quality (Javaid and Haleem, 2020).

According to the existing literature, the essence of I5.0 revolves around three key dimensions: the human factor, sustainability and resilience (Breque et al., 2021; Madsen and Berg, 2021; Romero and Stahre, 2021; Akundi et al., 2022; Grabowska et al., 2022). However, the literature also allows for the identification of a fourth dimension related to organizational strategy. This dimension enables the evaluation of barriers and enablers, transformative business models and innovation outcomes facilitating the implementation of I5.0 (Scuotto et al., 2017; Kohnová et al., 2019; Stentoft et al., 2019; Sony and Naik, 2020).

2.2. Technological advancements in I5.0

The transition from I4.0 to I5.0 is marked by the integration and advancement of several key technologies. These technologies not only enhance operational efficiency but also emphasize human-centric and sustainable approaches. Understanding these pivotal advancements, encompassing innovations from AI to Edge Computing, is essential as organizations navigate this evolution. These advancements are reshaping industrial landscapes by fostering connectivity, efficiency and innovation. In this study, we delve into the multifaceted realm of I5.0’s enabling technologies, elucidating their applications and implications for organizational strategy and decision-making. Table 2 provides a synthesis of the major enabling technologies driving the transition from I4.0 to I5.0, along with their applications and associated citations.

| Technology | Description | Application | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| IoE | Expands IoT to include people and organizations, fostering a fully connected ecosystem for intelligent interactions. | Comprehensive connectivity | Javaid and Haleem (2020) and Martynov et al. (2019) |

| AI | Empowers decision-making and enhances operations through machine learning algorithms, with applications in logistics, operations management and marketing. | Decision-making, optimization, innovation | Choi et al. (2022) and Javaid and Haleem (2020) |

| Cobots | Operate alongside human workers, enhancing efficiency and satisfaction. | Human–robot collaboration, automation | Javaid and Haleem (2020) |

| Blockchain | Provides secure and transparent data transmission, revolutionizing supply chain management. | Data security, supply chain transparency | Dubey et al. (2020) |

| Big Data | Enables the extraction of valuable insights from large datasets, driving strategic decision-making, fostering innovation and enhancing performance. | Predictive analytics, process optimization | Dubey et al. (2021) and Mishra et al. (2023) |

| Edge Computing | Facilitates low-latency data processing and real-time interactions by bringing computation closer to data sources. | Real-time monitoring, distributed computing | Javaid and Haleem (2020) |

| 5G and 6G | Provides high-speed wireless communication, fostering seamless connectivity and enabling new applications. | Real-time monitoring, high-speed cloud computing | Bhargava et al. (2022) |

Finally, it is important to highlight that the technological aspect plays a transversal role in all these dimensions of I5.0. Emerging technologies are key enablers driving the successful implementation of sustainability, the human factor and resilience in organizations. These technologies not only allow for process optimization and more informed decision-making but also foster the creation of safer, more efficient and adaptable work environments. By integrating advanced technologies into their organizational strategy, companies can fully capitalize on the opportunities offered by I5.0 to improve their long-term competitiveness, innovation and sustainability.

2.3. Dimensions of analysis for the implementation of I5.0

2.3.1. Sustainability

This new vision of the industry seeks a revolution in human resource development, aiming to build a society centered on the individual, where all citizens can lead fulfilling lives and demonstrate their maximum potential. In this industrial revolution, priority areas for creating new value through the use of emerging technologies are defined based on social needs such as healthcare, transportation, care for the elderly, business transactions, among others (Fukuyama, 2018). Identifying and solving crucial social problems in modern society guides organizations in the necessary advancements in social responsibility. In this context, health, environmental and socio-economic crises drive humanity toward a turning point where rapid scientific and technological innovations enable greater awareness and appreciation of human living conditions, as well as increased care for the planet.

I5.0 recognizes the industry’s capacity to achieve social objectives beyond employment and development, transforming into a sustainable source of development that considers the environmental limitations of the planet and prioritizes employee health. The concept of sustainability must be evaluated across different dimensions, encompassing financial, environmental and social aspects (Magee et al., 2013; Stock and Seliger, 2016; Stock et al., 2018). From a financial perspective, the focus is on efficiency in the design, development and delivery of products and services, relying on the economic viability of the involved processes. This economic sustainability is crucial as it ensures the organization’s long-term existence.

In the environmental context, the emphasis is on combating pollution, efficiency and the proper use of natural resources, which are crucial in the current challenges facing the planet. The social aspect addresses issues related to equal opportunities, solving social problems and needs, ethical behavior, equity and inequality.

2.3.2. Human factor

In I5.0, human workers and their well-being are placed at the core of the production process. Current research on I5.0 emphasizes the need for humanization in future industries, where humans play a key role. This human-centered industrial approach puts fundamental human needs and interests at the center of the production process and utilizes new technologies to generate prosperity beyond employment and growth (Kumar et al., 2021).

The goal of I5.0 is to create a society where both economic development and the resolution of social challenges are achieved, allowing people to enjoy a high quality of life that is fully active and comfortable. It is a society that will meticulously address the diverse needs of individuals, regardless of their region, age, gender, language, etc., providing them with the necessary products and services (Fukuyama, 2018). To make this a reality, companies need individuals with different skills and competencies who are willing to embrace changes within their organizational structure and in production lines (Gaiardelli et al., 2021).

In the pursuit of human well-being, it is important to understand that in the I5.0 ecosystem, people can be classified in various ways depending on the context: consumers, employees, enthusiasts and businesses (Carayannis et al., 2022). According to Choi et al. (2022), there is a difference between employee well-being and consumer well-being. Consumers play more roles than just those who purchase the product or service. They can participate in product design, and their effort can enhance the value of the process. Employee well-being focuses on humans working not only for money and tangible benefits but also for their own satisfaction. Through the implementation of cutting-edge technologies, increased automation will positively influence employment in various areas, opening more job opportunities for creative individuals and enhancing human efficiency. This is expected to lead to a higher level of cooperation between workers, managers, and these new technologies (Breque et al., 2021). Finally, employee safety in the workplace will be significantly improved as the application of technology, such as AI-based Collaborative Robots (Cobots), can perform high-risk tasks and reduce accidents, enhancing human well-being (Mamoona, 2021).

2.3.3. Resilience

Understanding resilience as the ability to flexibly cope with change, considering that value chains and markets are constantly affected by various disruptive changes, it becomes necessary to evolve production processes toward flexibility to withstand such changes. Traditionally, processes in a production line or product development, from concept and requirements to operation and maintenance, used to be quite static and sequential. The digitization of the industry has transformed this approach by making the entire product lifecycle more automated (Urgese et al., 2020).

The supply chain must be able to adapt to current challenges related to the evolution of society and new business requirements. In this context, a set of disruptive technologies can help supply chain management integrate mass customization into its production systems, referred to as Supply Chain 5.0 by Frederico (2021). Furthermore, the industry must swiftly adapt to the increasingly dynamic environment of the value chain by integrating Industry 5.0 technologies to maintain its role as a sustainable driver (Sindhwani et al., 2024). The benefits of I5.0 for the industry are diverse, ranging from better talent attraction and retention, energy savings to increased resilience in all processes (Breque et al., 2021).

Since the era of I4.0, automation, based on the development and application of disruptive technologies, emerged as the main force to improve efficiency in operations management. Operations management must be aware of new social trends that strongly impact business, compelling companies to significantly adapt how they organize and interconnect their supply chains (Choi et al., 2022). Some authors emphasize the importance of using technology as a means to create a conducive environment for I5.0, serving as the foundation for its implementation (Martynov et al., 2019). However, new technological approaches that could align with I5.0 expectations have been identified (Frederico, 2021). Javaid and Haleem (2020), consider 17 vital components for the success of I5.0 (Big data, Cobots, Smart Sensors, IoT, Internet of Everything (IoE), AI, Multi-agent System, Digital Ecosystem, Smart Manufacturing, Complex Adaptive System, Smart Material, 3D printing, 4D printing, 5D printing, 3D scanning, Holography, Virtual Reality). These components promote a new business concept, enhancing the flexibility of smart manufacturing and reducing waste by manufacturing according to customer demand.

2.3.4. Organizational strategy

Organizational strategy refers to a set of planned and coordinated actions that an organization implements to achieve its long-term objectives and goals. It involves identifying an organization’s resources, capabilities, strengths and weaknesses, as well as assessing the opportunities and threats in its operating environment. Based on this evaluation, objectives are set, and action plans are defined to achieve them. Its scope extends beyond supply chains or manufacturing; it encompasses all aspects of the organization, the industry and even society (Brettel et al., 2014). Even from its predecessor, I4.0, the importance of clearly defining an organizational strategy for optimal implementation and development was evident. Therefore, the organizational strategy must be designed for the substantial initial investments that must be made in technology, up to managing innovation within the organization. This requires companies to understand that, for the optimal development and implementation of this industrial advancement, they must relate it to their specific business domain from their organizational strategy (Sony and Naik, 2020).

The impact of I4.0 on organizational strategy has been decisive (Sony and Naik, 2020). Changes that have occurred within an organization due to its development involve the organization’s relationship with nature: developments in resource efficiency and sustainability of manufacturing systems; organization and local communities: leading to greater geographic proximity and acceptance, and integration of customers into design and manufacturing processes; organization and value chains: distributed and responsive manufacturing through collaborative processes enables massive customization of products and services; organization and humans: this includes human-oriented interfaces and better working conditions (Santos et al., 2017).

Companies had already faced difficulties in grasping the understanding of I4.0 and relating it to their specific business domain. For example, it has been challenging for companies to appreciate its scope as a vision or mission (Schumacher et al., 2016). Furthermore, the interpretation of means versus ends is not clear, generating confusion for organizations. This lack of understanding of the concepts of I4.0 and 5.0, in clear terms regarding existing business, has generated confusion in the generation of organizational strategy. In other words, it has created difficulty in identifying strategic action areas for its proper implementation (Sony and Naik, 2020).

In this regard, it cannot be ignored that many challenges associated with I5.0, which were already being identified from I4.0, such as financial capacity, data security issues, maintaining the integrity of the production process, IT maturity, and knowledge competencies, among others (Ghobakhloo, 2018). However, identifying these challenges or barriers will eventually enable making decisions that facilitate the adoption or implementation of I5.0 within organizations. As mentioned earlier, I5.0 has the potential to transform the business landscape through a significant increase in productivity. While there are already significant differences between companies today, with the implementation of I5.0, the performance gap may become even larger and the risks for laggards potentially insurmountable (Liboni et al., 2019; Llinas Sala and Abad Puente, 2019). In this sense, it is important to recognize the facilitators driving the implementation of I5.0, which are related to technological pre-existence, managerial commitment, production efficiency, market and competitiveness, competent employees and government policies.

Organizational strategy and I5.0 are closely related, as the effective implementation of organizational strategy can help a company make the most of the opportunities offered by I5.0. For example, a company that adopts an innovation strategy may be better positioned to develop and market advanced technological solutions that meet consumer needs in a digital economy. Similarly, a company that adopts a sustainability-based business model may be better positioned to seize market opportunities in an economy that values sustainability and corporate social responsibility.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the technological aspect plays a transversal role in all these dimensions of I5.0. Emerging technologies are key enablers driving the successful implementation of sustainability, the human factor and resilience in organizations. These technologies not only allow for process optimization and more informed decision-making but also foster the creation of safer, more efficient and adaptable work environments. By integrating advanced technologies into their organizational strategy, companies can fully capitalize on the opportunities offered by I5.0 to improve their long-term competitiveness, innovation and sustainability.

2.4. Methodological aspects in the literature

The assessment of challenges faced by companies in implementing I5.0 is crucial for a better understanding of its applications and overcoming issues encountered by its predecessors. Consequently, it is essential to examine the challenges decision-makers encounter when attempting a successful transition to I5.0. However, this task is not straightforward as it involves numerous qualitative factors related to the decision-making process.

Several studies have employed multicriteria methods to evaluate various analysis elements for the implementation of I4.0 and 5.0. For instance, Nimawat and Gidwani (2021) identified priorities of important factors for implementing I4.0 in manufacturing companies using techniques such as AHP and the Analytic Network Process (ANP). Similarly, Luthra and Mangla (2018) ranked identified dimensions of challenges for implementing I4.0 for supply chain sustainability using AHP, revealing the prominence of organizational challenges, followed by technological, strategic and legal/ethical challenges.

Sevinc et al. (2018) established a hierarchical structure to analyze difficulties in the transition process of Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) to I4.0, employing criteria like innovation, organization, environment and financial aspects. Sharma et al. (2022) utilized multicriteria approaches (AHP-ELECTRE-DEMATEL) to highlight issues in adopting high-tech innovations and proposed an I5.0 framework. Sindhwani et al. (2022) proposed a framework to analyze I5.0 enablers for achieving sustainability, integrating human values with technology. Moreover Nayeri et al. (2023) investigated attributes of responsive supply chains based on I5.0 dimensions using Multiple Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) methods. They identified key criteria and proposed a hybrid model based on the stochastic Best–Worst Method (BWM) and Fuzzy Vlse Kriterijumsk Optimizacija Kompromisno Resenje (FVIKOR). Other studies incorporate FIS analysis to evaluate supplier performance concerning sustainability criteria in I4.0 (Fallahpour et al., 2021; Jain and Singh, 2021).

In this context, it is pertinent to justify the choice of AHP and FIS methodologies for prioritization, despite the variety of advanced tools and methods available in the current scenario. The decision is based on their complementarity, simplicity, robustness and flexibility, as well as their validation in previous studies on emerging technologies. These methodologies have proven effective in evaluating multiple criteria and solving complex problems, making them suitable for addressing the diversity of dimensions involved in the implementation of I5.0.

3. Methodology

For this study, we employ the AHP in conjunction with a FIS to address decision-making challenges faced by companies aiming to successfully transition to I5.0. The primary goal is to enhance the accuracy and reliability of alternative assessments in an environment characterized by uncertainty and imprecision. AHP is utilized as a structured method to determine criteria weights and establish a hierarchy among them. Through pairwise comparisons based on Saaty’s general scale values (Saaty, 1988), both local and global weights are derived, establishing their relative importance in the assessment process under study.

Subsequently, the FIS is integrated into the analysis. This FIS takes inputs from both the criteria weights obtained from AHP and the evaluations of alternatives for each criterion. Employing fuzzy inference rules, it robustly produces final evaluations for each alternative, considering the inherent uncertainty in the problem.

Figure 1 outlines the research methodology, illustrating the sequential steps from the literature review to the interpretation of inference maps. The combination of AHP and FIS leverages the strengths of both methodologies. AHP provides a solid framework and an initial basis for criteria weighting, while FIS handles uncertainty and imprecision, mitigating the issue of rank reversal. Furthermore, FIS can adapt to the specific characteristics of the problem, allowing for the adjustment of fuzzy parameters and the definition of custom inference rules.

Fig. 1. Steps of the research methodology.

4. Model Development

4.1. Hierarchy (dimensions and criteria)

In the context of I5.0, four key factors have been identified (see Table 3). First, the “Human Factor” focuses on the synergy between humans and autonomous machines, knowledge generation based on connectivity and the recognition of human labor. “Sustainability” emphasizes addressing environmental, social and financial dimensions in production, acknowledging the role of I5.0 in meeting social and environmental goals. “Resilience” centers on improving production through digitization and optimizing the supply chain. Lastly, “Organizational Strategy” considers barriers and enablers for the strategic implementation of I5.0, including aspects such as understanding its importance, financial resources and innovation in new business models. These dimensions are crucial for evaluating and making decisions in the context of I5.0.

| 1st hierarchy | 2nd hierarchy | Based on |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | Financial sustainability | Carayannis et al. (2022), Foresti et al. (2020), Orlova (2021), Pasi et al. (2020), Potocan et al. (2021), Rauch (2020) and Rojas et al. (2021) |

| Environmental sustainability | ||

| Social sustainability | ||

| Human factor | Employee well-being | Kamble et al. (2020) |

| New skills and competencies of human capital | Bongomin et al. (2020) and Mitchell and Guile (2022) | |

| Collaboration | Orlova (2021) and Rega et al. (2021) | |

| Resilience | Flexible business processes | Dubey et al. (2021), Piprani et al. (2022) and Rajesh (2021) |

| Adaptable production capacity | Parhi et al. (2022) | |

| Resilient value chain | Akundi et al. (2022), Bahrami and Shokouhyar (2022), Dubey et al. (2020) and Martynov et al. (2019) | |

| Technological capacity | Kamble et al. (2020) and Martynov et al. (2019) | |

| Anticipation | Gehrlein et al. (2019) and Nayeri et al. (2023) | |

| Recovery | ||

| Organizational strategy | Barriers to the implementation | Chauhan et al. (2021), Stentoft et al. (2019) and Türkeş et al. (2019) |

| Enablers for the implementation | Kohnová et al. (2019), Stentoft et al. (2019) and Türkeş et al. (2019) | |

| Transformative business models | Shah et al. (2020) | |

| Innovation outcomes | Huang and Jia (2022) and Scuotto et al. (2017) |

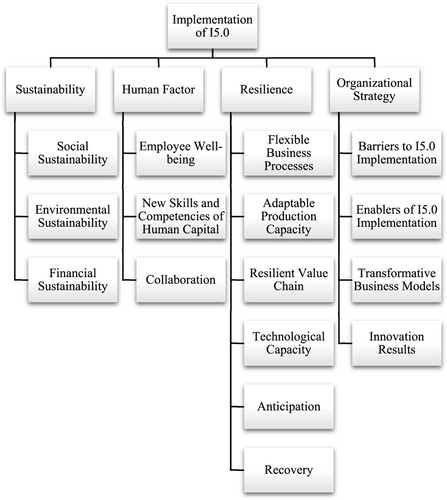

Figure 2 provides a hierarchical view of the proposed conceptual model with key factors and criteria to assess for an effective implementation of I5.0. The criteria under consideration play a crucial role in the evaluation and success of the transition to I5.0, and their detailed analysis will better understand the influencing factors in this industrial transformation. In the context of this work, the criteria will be assessed on a 10-point scale based on relevant indicators (which, not being globally standardized, can be adopted with different contextual perspectives depending on the country where the model is applied).

Fig. 2. Criteria for the assessment of the implementation of I5.0.

4.2. AHP and consensus application (Weight estimation)

AHP has been widely employed across various disciplines, notably in decision-making, project management, engineering and economics. Its significance lies in its ability to address complexity and subjectivity in decision problems, enabling a more rational and well-founded process. Saaty (1996) emphasizes its capacity to handle complex problems in a clear and structured manner. Compared to other multicriteria techniques like TOPSIS and VIKOR, AHP stands out for reducing subjectivity, being universal and consistent in data verification and handling uncertainty in criteria evaluation. Another advantage is its ability to facilitate consensus among decision-makers, especially in group settings, by enhancing communication. Condon et al. (2002) note that AHP identifies and incorporates inconsistencies in qualitative judgments of decision-makers, using a Consistency Index (CI) and a Consistency Ratio (CR). An RC < 0.1 is considered acceptable; otherwise, the decision-maker is asked to reevaluate their judgments. Overall, AHP combines rational and intuitive approaches to select the best-evaluated alternative based on various criteria, relying on expert experience. Its implementation follows a five-step process, from hierarchical decomposition to the final ranking of options.

The levels of importance or weighting of criteria are determined through pairwise comparisons. These comparisons are made using a scale. For n attributes, the paired comparison of element i with element j is placed in the position aijaij of the Pairwise Comparison Matrix (PCM) A, as shown in the following equation :

At each level, the relative importance weights of the criteria are determined using PCMs with Saaty’s 9-point scale. In this study, the relative weights of each criterion are calculated from these PCMs using the components of the normalized eigenvector associated with its highest eigenvalue. Then, the normalized vector of overall weights for all criteria is obtained at the lowest level of the hierarchical structure by multiplicatively combining the local weights from the top of the hierarchy to the lowest level. To check the consistency of a PCM and validate the weights of its eigenvector, the following metrics were calculated: the “CI”, the “Random Index (RI)” and the “CR”. The latter should not exceed the threshold associated with the PCM dimension (otherwise, the PCM must be modified until this condition is met). Tables 4–7 show, as an example, the PCMs for level 2 criteria, as well as the eigenvectors of the criterion weights estimated from their corresponding normalized matrices.

| G04 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | Wi | MMULT | VMC | Consistency | ||||

| C1 | 1.000 | 2.079 | 1.363 | 0.452 | 0.476 | 0.434 | 0.454 | 1.364 | 3.004 | 0.002 | CI |

| C2 | 0.481 | 1.000 | 0.777 | 0.217 | 0.229 | 0.247 | 0.231 | 0.694 | 3.002 | 0.525 | RI |

| C3 | 0.734 | 1.287 | 1.000 | 0.331 | 0.295 | 0.318 | 0.315 | 0.946 | 3.003 | 0.003 | CR |

| 2.215 | 4.366 | 3.140 | 1.000 | 0.050 | Min |

| G09 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | Wi | MMULT | VMC | Consistency | ||||

| C4 | 1.000 | 1.214 | 0.888 | 0.339 | 0.333 | 0.343 | 0.338 | 1.016 | 3.000 | 0.000 | CI |

| C5 | 0.824 | 1.000 | 0.699 | 0.279 | 0.274 | 0.270 | 0.275 | 0.824 | 3.000 | 0.525 | RI |

| C6 | 1.126 | 1.430 | 1.000 | 0.382 | 0.392 | 0.386 | 0.387 | 1.161 | 3.000 | 0.000 | CR |

| 2.949 | 3.644 | 2.588 | 1.000 | 0.050 | Min |

| G11 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 | C11 | C12 | Wi | MMULT | VMC | Consistency | |||||||

| C7 | 1.000 | 1.764 | 2.163 | 2.177 | 1.772 | 1.430 | 0.267 | 0.287 | 0.324 | 0.294 | 0.232 | 0.182 | 0.264 | 1.645 | 6.222 | 0.04 | CI |

| C8 | 0.567 | 1.000 | 1.647 | 0.892 | 0.916 | 1.800 | 0.151 | 0.163 | 0.247 | 0.120 | 0.120 | 0.229 | 0.172 | 1.070 | 6.229 | 1.25 | RI |

| C9 | 0.462 | 0.607 | 1.000 | 1.507 | 1.813 | 1.559 | 0.123 | 0.099 | 0.150 | 0.203 | 0.237 | 0.199 | 0.169 | 1.037 | 6.156 | 0.03 | CR |

| C10 | 0.459 | 1.121 | 0.664 | 1.000 | 1.190 | 1.005 | 0.122 | 0.183 | 0.100 | 0.135 | 0.156 | 0.128 | 0.137 | 0.847 | 6.171 | 0.10 | Min |

| C11 | 0.564 | 1.091 | 0.552 | 0.840 | 1.000 | 1.057 | 0.150 | 0.178 | 0.083 | 0.113 | 0.131 | 0.135 | 0.132 | 0.810 | 6.155 | ||

| C12 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 6.14 |

| G11 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | Wi | MMULT | VMC | Consistency | |||||

| C1 | 1.000 | 0.524 | 1.153 | 0.959 | 0.208 | 0.213 | 0.241 | 0.164 | 0.207 | 0.833 | 4.035 | 0.011 | CI |

| C2 | 1.908 | 1.000 | 1.979 | 2.327 | 0.396 | 0.407 | 0.414 | 0.399 | 0.404 | 1.630 | 4.034 | 0.882 | RI |

| C3 | 0.868 | 0.505 | 1.000 | 1.548 | 0.180 | 0.205 | 0.209 | 0.265 | 0.215 | 0.868 | 4.038 | 0.013 | CR |

| C4 | 1.043 | 0.430 | 0.646 | 1.000 | 0.216 | 0.175 | 0.135 | 0.171 | 0.174 | 0.702 | 4.026 | 0.090 | Min |

After ensuring the consistency of the initial judgment matrices from all experts in PCM: (xk,ti,j)xk,ti,j), they were aggregated using the weighted geometric mean according to the expression: Gt=gti,j=∏mk=1(xk,ti,j)ρkGt=gti,j=∏mk=1(xk,ti,j)ρk (Aczél and Saaty, 1983). As a practical example, the application of the method is illustrated in the evaluations of experts in the first hierarchy, corresponding to the factors Sustainability (F1), Human Factor (F2), Resilience (F3) and Organizational Strategy (F4). In this case, the aggregated matrix for the expert team at time t = 0 (G0) is shown in Table 8.

| G0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 |

| F1 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.29 | 2.26 |

| F2 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.81 |

| F3 | 0.78 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| F4 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 1.04 | 1.00 |

Next, the iterative consensus method developed by Dong and Saaty (2014) was applied. Under this method, in each iteration “t→t+1t→t+1”, the expert furthest from the current aggregated matrix was encouraged to modify their individual PCM. The distance of expert “k” PCM to the current aggregated matrix — the Group Compatibility Index of expert “k” — was calculated as follows: GCIk=d(xki,j,gi,j)=1n2∑ni=1∑nj=1gi,j⋅xkj,i, where “n” represents the number of criteria.

In the event that the last expert “h” accepted the modification, the components were calculated according to the expression: xh,t+1i,j=(xh,ti,j)α⋅(gti,j)(1−α), where α∈ [0–1] is the coefficient of the expert’s “h” willingness to change in that iteration — higher values closer to zero. If the stochastic weight of each expert “z” remained constant (ρt+1z=ρtz) the new aggregated matrix (Gt+1) is calculated according to the weighted geometric mean applied at instant “t + 1”, thus moving on to the next iteration.

If the last expert “h” rejected the modification, their stochastic weight was reduced according to the expression: ρt+1h=ρth⋅β+ρth⋅(1−β)⋅ρth, increasing the weight of the rest of the experts “z” according to the expression: ρt+1z=ρtz+ρtz⋅(1−β)⋅ρtz, where β∈ [0–1] is the weight adjustment coefficient proposed by the moderator in that iteration: the more “h” is penalized, the closer it gets to zero. The aggregated matrix (Gt+1) is calculated according to the weighted geometric mean applied at moment t+1.

The process is iteratively repeated with the aim of achieving a high degree of consensus among experts and minimizing discrepancies in their assessments. The results include the ultimate weights assigned to each factor in the hierarchy, reflecting their relative importance in the evaluation. Iterations continue until one of the following three stopping conditions is met: (a) when the distance of all experts to the previous aggregated matrix is less than 1.01 (corresponding to a 1% variation), (b) when a pre-established maximum number of iterations is reached — in our case, this threshold was set at 10 — or (c) when all experts refuse to change their opinion.

For the first iteration, once the distances (GCIk), are calculated, a consultation is carried out with the expert who has the greatest distance, aiming to determine whether they are willing to accept or reject the change in their assessments (Fig. 3). The expert selected for this case is expert number 2, whose distance value GCI3 is 1.4246. The expert 2 is presented with the request to accept the change in their PCM, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Expert 2 confirms their acceptance of the proposed change in the matrix.

Fig. 3. First iteration.

Fig. 4. Change in the comparison matrix of expert 2.

Once again, the G matrix is recalculated (Fig. 5), and the stopping criteria are checked. In this case, it is found that the value of α is less than 0.85 (α = 0.45), and the value of Δ is greater than 0.2 (Δ = 0.42). Therefore, none of the established stopping conditions are met.

Fig. 5. Center of gravity matrix G1.

For practical purposes, following the previous example, Fig. 6 shows the sixth iteration, in which the stopping conditions are checked to determine if the iterations should end (the value of α is 0.87), which meets the first stopping condition (α>0.85). The value of Δ is 0.05, which meets the second stopping condition (Δ<0.2). Since both stopping conditions are met, the iterations end. Next, the calculation of the final weights is carried out using the G5 matrix in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6. Sixth iteration.

Fig. 7. Center of gravity matrix G1.

Likewise, it is crucial to determine the relative importance of each expert in achieving the final consensus, with the purpose of assigning appropriate weights to the system. The assessment provided by a highly experienced expert differs from that of someone with less background in the field. To address this issue, the weight of each expert is established by considering variables such as their professional trajectory, educational level and competence in areas related to I5.0. The experts selected for the panel bring vast experience and specific knowledge in crucial areas for the transition to I5.0. In the panel discussions, the experts not only explored Industry 5.0’s definition, challenges, opportunities and critical technologies (AI, IoT, robotics) but also emphasized human-centric approaches, sustainability and resilience. Practical implementation insights were shared through case studies and pilot projects, highlighting different stages from initial exploration to advanced integration. These discussions underscored the importance of productivity, innovation and adaptive systems, providing a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of transitioning to I5.0. Table 9 outlines the chosen experts, detailing origin, Industry 5.0 experience, sector and focus. These experts provided highly competitive insights, which were processed to yield quantitative results.

| Expert | Origin | I5.0 experience | Origin sector | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | Spain | 20 years in computer system integration in organizations. Contributions of the human factor to I4.0 and 5.0. | Industry (70%), academia (30%) | Human factor in I4.0 and 5.0 |

| Expert 2 | USA | 25 years in research on emerging technologies. Involved in I4.0 and 5.0 pilot projects. | Academia (60%), industry/consulting (40%) | Transition to I5.0 |

| Expert 3 | Germany | 30 years in organizational strategy. Publications on I4.0 and 5.0. | Industry (20%), academia (80%) | Transition I4.0 to 5.0 |

| Expert 4 | Colombia | 15 years in manufacturing digitization and automation. Direct experience in I4.0 and 5.0 projects. | Academia (100%) | Industrial automation |

| Expert 5 | Italy | 10 years in supply chain management. Focus on the adoption of emerging technologies. | Academia (80%), industry/consulting (20%) | I4.0 in the supply chain |

For the calculation of the importance weights of each expert “”, Eq. (3) from Dong and Saaty (2014) is followed, where the following parameters are distinguished:

| – | PEi denotes years of professional experience; | ||||

| – | max{PEk} denotes maximum of years of experience among all experts involved in the process; | ||||

| – | ESii denotes years of specialized experience in the study of I5.0; | ||||

| – | max{ESk} denotes maximum of years of experience in the study of I5.0 among all experts involved in the process; | ||||

| – | ADi denotes characterizes the academic degree of the expert, where 1 represents a bachelor’s degree, 2 a master’s degree and 3 a doctorate; | ||||

| – | max{ADk} denotes the maximum of this parameter among all experts; | ||||

| – | KCm,i denotes the expert’s knowledge in different fields related to I5.0; | ||||

| – | n denotes four fields representing their expertise in the following knowledge areas: Sustainability, Human Factor, Resilience, Organizational Strategy. | ||||

| Relevance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert competence | Attribute | Exp1 | Exp2 | Exp3 | Exp4 | Exp5 |

| Years of professional activity | PA | 25 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 30 |

| Years of specialized experience in the area | SE | 9 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 12 |

| Academic degree | AD | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Knowledge field | ||||||

| Sustainability | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Human factor | 5 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | |

| Resilience | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Organizational strategy | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| Expert weight | 0.905 | 0.726 | 0.845 | 0.655 | 0.869 | |

| Normalized | 0.226 | 0.182 | 0.211 | 0.164 | 0.217 |

It can be observed that experts 1, 3 and 5 have a roughly similar influence on their responses (between 21% and 22%). In contrast, experts 2 and 4 have a lower weighting compared to the rest (18.2% and 16.4%, respectively) due to having less experience in the fields of I5.0 and in their professional activity.

Although AHP is a well-known method for multicriteria decision-making problems, especially when qualitative evaluation is needed, it cannot handle uncertain variables (Wang et al., 2009). To mitigate these issues, this study integrates a FIS, whose knowledge structure is designed based on the weights obtained with AHP, allowing the independent assessment of each new alternative. Thus, the inputs needed to assess the degree of I5.0 implementation in an SME will be the criteria weights (previously determined with AHP) and the evaluations that the company presents in the lower-level criteria of the model.

4.3. FIS

FIS is based on the use of fuzzy set theory (Zadeh, 1965), allowing the modeling of complex systems in environments where the variables under assessment are uncertain or subject to high levels of subjectivity in their determination, as is the case in this study.

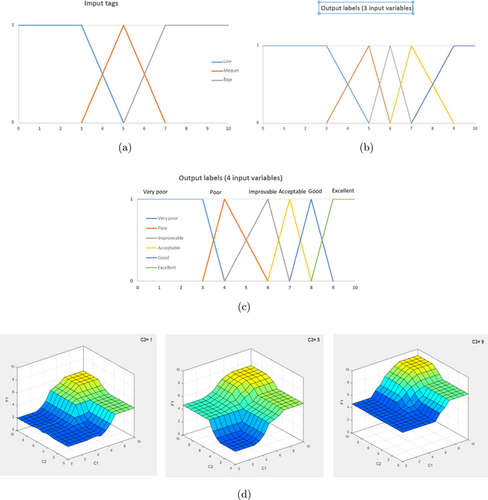

In a fuzzy set, the membership of an element in that set is associated with a truth value in the range [0,1], enabling multivalued logic — in contrast to classical sets, where their bivalent logic {0,1} requires an element to belong completely or not at all. Thus, membership functions are often defined — linked to these sets — either in a linear (triangular or trapezoidal) or curved (Gaussian, sigmoidal, pi, among others) manner. Fuzzy numbers are normal (unit-height) and convex fuzzy sets, representing linguistic concepts. For example, the satisfaction variable (whose classical values are usually measured in a 0–10 range) could be fuzzily conceptualized when its assignable values are associated with different fuzzy numbers (labels) — e.g. “Low (L)”, “Medium (M)”, “High (H)” — partitioning the domain accordingly (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Subsystems FIS.

FIS allow the processing of linguistic concepts (fuzzy numbers) to relate the input and output variables of a valuation model using fuzzy logic. Three processes are required prior to inference development. First, the domains of the input and output variables of each subsystem must be partitioned using linguistic concepts. Second, a set of fuzzy conditional rules that incorporate the evaluation knowledge governing the inferential process in each subsystem must be established. Lastly, the inference subsystems must be linked to obtain the final crisp assessment of each alternative.

Methodologically, our work introduces the novelty of integrating weights obtained through AHP with the fuzzy definition of variables in the proposed conceptual model, facilitating the automatic generation of initial knowledge rules for evaluation. This avoids the traditional cost of obtaining rule bases through consensus rounds among experts or reasoning algorithms based on previously solved cases.

Once the fuzzy partitions of the variables, the inference rules of the system and the input data for each SME under assessment (numeric crisp evaluations of the 16 lowest-level criteria of the fuzzily conceptualized model) are defined, the inference development can proceed (in our case, using the Mamdani type) through the MATLAB Fuzzy v2 toolbox. The inference process unfolds in five steps: (1) fuzzification of crisp input values; (2) application of logical operators in the antecedents of each rule; (3) implication of the antecedent of each rule to its respective consequent; (4) aggregation of consequents from all activated rules and (5) defuzzification of the final aggregate (Mamdani and Gaines, 1981).

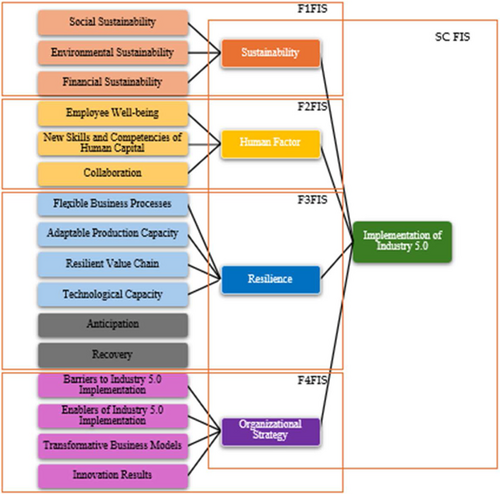

In our case, the global FIS linked to the proposed conceptual model consists of five chained inference subsystems, as illustrated in Fig. 9: four (F1.fis to F4.fis) to infer the crisp values of each SME’s factors — based on the scores determined for its 16 criteria — and one final (SC.fis) to infer its overall assessment — based on the previously inferred values for its factors. Thus, the evaluations obtained for the output variables of an FIS at a specific level of the hierarchy subsequently serve as input values in the FIS of the immediately higher hierarchical level.

Fig. 9. FIS subsystems of the proposed valuation model.

To measure the degree of alignment with I5.0 for any SME, the following procedure would be followed:

Design the FIS governing the fuzzy valuation model (defining their partitions in the range [0–10] and their rule bases): F1.fis, F2.fis, F3.fis, F4.fis, SC.fis.

Calculate the scores [0–10] assignable to the sixteen lowest-level criteria in the proposed model for each SME. To do this, the influential indicators in the specific determination of each criterion should be measured, and their values should be normalized to the 0–10 scale.

Infer the [0–10] values of the four factors for each SME from the previous scores in their respective FIS (F1.fis to F4.fis).

Infer the overall [0–10] value for each SME from the values inferred for its four factors from the previous step.

For a better interpretation of results, it is advisable that each FIS has no more than four input variables. Therefore, the criteria “Anticipation” and “Recovery” have been excluded from the fuzzy subsystem F3.fis. Both criteria have the least influential weights in this subsystem, according to the consensual AHP results. Considering them would have required generating 36 rules, greatly complicating the interpretation of factor F3 in terms of its dependent criteria. After excluding the weights of these two less influential criteria, the weights of the remaining criteria must be recalculated and normalized to sum to unity at the local level.

4.4. Variable partitioning

For the design of partitions, a method based on two-tuple pairs was employed (Herrera and Martínez, 2000). This approach allows combining linguistic preference ratings given by the expert panel regarding a set of potential assignable cores for each label. The two-tuple pair with the highest agreement value will determine the core assigned to the label under analysis. Subsequently, once these cores are established, the partitions for each variable are obtained through central symmetry to ensure their robustness.

In the study, the number of label categories was fixed as follows. For input variables, it was divided into three categories: “Low” (L), “Medium” (M) and “High” (H). Regarding output variables, the number of labels was determined based on the number of input variables involved. If there were three input variables, five labels were established, while if there were four input variables, seven labels were used. It is essential to highlight that all these labels are within the range of 0 to 10, representing the value range considered in the study.

To define the categories for all variables, fuzzy numbers with trapezoidal or triangular shapes were chosen, as they are particularly suitable for expressing imprecise assessments from a linguistic perspective, which may arise from various sources of information. To illustrate this approach, Figs. 10(a)–10(d) provide a visual representation of the final partitioning of input variables in all subsystems. In this graphical representation, it is shown how the labels are distributed according to the previously agreed core structure.

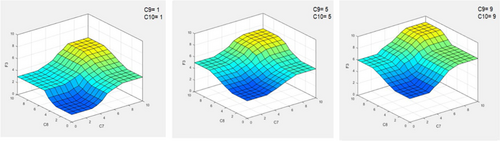

Fig. 10. (a) Partition of input variables, (b) representation of output labels with three input variables, (c) representation of output labels with four input variables and (d) inference maps of subsystem F1 with C3 = 1, C3 = 5, C3 = 9.

In this graphical representation, it is shown how the labels are distributed according to the previously agreed core structure.

4.5. Rule definition

Once the partitions of all variables are defined, a distance-based method, relying on the weights obtained through AHP, was used to automatically generate rules for all subsystems. This represents one of the main methodological contributions of this work. In each subsystem, as many knowledge rules were generated as possible combinations of labels assignable to their input variables — 27 (81) rules in subsystems with 3 (4) input variables, respectively. In each rule, the weighted trapezoid of the labels defined in its antecedent is calculated, according to the weights obtained previously in AHP. It is important to note that when an input variable is of type “min”, the labels of its partition must be inverted before processing to obtain the weighted trapezoid associated with each rule. Equation (4) shows the calculation of the four vertices of the weighted trapezoid for the second rule of the “F1.fis” subsystem of the model (see rule “R02” in Table 11).

| Max | Max | Max | WC1 = 0.4539 | WC2 = 0.2312 | WC3 = 0.3149 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule | C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | Weighted trapezes (WT) | ||||||||||||

| R01 | L | L | L | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 |

| R02 | M | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0. 94 | 1. 57 | 3. 63 | 5. 63 | ||

| R03 | H | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.57 | 2.20 | 5.20 | 6.57 | ||

| R04 | M | L | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0.69 | 1.16 | 3.46 | 5.46 | |

| R05 | M | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 1.64 | 2.73 | 4.09 | 6.09 | ||

| R06 | H | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 2.27 | 3.36 | 5.67 | 7.04 | ||

| R07 | H | L | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 1.16 | 1.62 | 4.62 | 6.16 | |

| R08 | M | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 2.10 | 3.19 | 5.25 | 6.79 | ||

| R09 | H | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 2.73 | 3.82 | 6.82 | 7.73 | ||

| R10 | M | L | L | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 1.36 | 2.27 | 3.91 | 5.91 |

| R11 | M | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 2.31 | 3.84 | 4.54 | 6.54 | ||

| R12 | H | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 2.94 | 4.47 | 6.11 | 7.48 | ||

| R13 | M | L | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2.06 | 3.43 | 4.37 | 6.37 | |

| R14 | M | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 7.00 | ||

| R15 | H | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3.63 | 5.63 | 6.57 | 7.94 | ||

| R16 | H | L | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2.52 | 3.89 | 5.53 | 7.06 | |

| R17 | M | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3.46 | 5.46 | 6.16 | 7.69 | ||

| R18 | H | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 4.09 | 6.09 | 7.73 | 8.64 | ||

| R19 | H | L | L | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2.27 | 3.18 | 6.18 | 7.27 |

| R20 | M | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3.21 | 4.75 | 6.81 | 7.90 | ||

| R21 | H | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3.84 | 5.38 | 8.38 | 8.84 | ||

| R22 | M | L | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2.96 | 4.33 | 6.64 | 7.73 | |

| R23 | M | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3.91 | 5.91 | 7.27 | 8.36 | ||

| R24 | H | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 4.54 | 6.54 | 8.84 | 9.31 | ||

| R25 | H | L | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3.43 | 4.80 | 7.80 | 8.43 | |

| R26 | M | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 4.37 | 6.37 | 8.43 | 9.06 | ||

| R27 | H | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 5.00 | 7.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | ||

In each rule, once these distances to all potentially assignable labels to their output variable “F1” (in this case, five labels) are calculated, the label for which the distance is minimum will be assigned. This assignment approach ensures that the system makes coherent and meaningful decisions according to the input conditions. Table 12 illustrates, in each rule, the distance calculations to assignable labels, the minimum distance and the labels finally assigned to the output variable.

| Distances to assignable labels for the output variable | Final | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule | Deficient | Improvable | Acceptable | Good | Excellent | MIN | Assigned label |

| R01 | 0.00 | 3.41 | 4.48 | 5.53 | 7.52 | 0.00 | Deficient |

| R02 | 1.10 | 2.33 | 3.40 | 4.45 | 6.47 | 1.10 | Deficient |

| R03 | 2.04 | 1.76 | 2.66 | 3.61 | 5.51 | 1.76 | Improvable |

| R04 | 0.80 | 2.62 | 3.69 | 4.74 | 6.75 | 0.80 | Deficient |

| R05 | 1.90 | 1.54 | 2.61 | 3.67 | 5.71 | 1.54 | Improvable |

| R06 | 2.80 | 1.16 | 1.90 | 2.82 | 4.73 | 1.16 | Improvable |

| R07 | 1.49 | 2.14 | 3.12 | 4.11 | 6.05 | 1.49 | Deficient |

| R08 | 2.55 | 1.17 | 2.06 | 3.03 | 4.99 | 1.17 | Improvable |

| R09 | 3.53 | 1.45 | 1.66 | 2.32 | 4.05 | 1.45 | Improvable |

| R10 | 1.58 | 1.85 | 2.93 | 3.98 | 6.01 | 1.58 | Deficient |

| R11 | 2.67 | 0.81 | 1.87 | 2.93 | 4.99 | 0.81 | Improvable |

| R12 | 3.55 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 2.06 | 3.99 | 0.93 | Improvable |

| R13 | 2.38 | 1.08 | 2.15 | 3.20 | 5.25 | 1.08 | Improvable |

| R14 | 3.48 | 0.39 | 1.14 | 2.18 | 4.25 | 0.39 | Improvable |

| R15 | 4.34 | 1.28 | 0.76 | 1.32 | 3.23 | 0.76 | Acceptable |

| R16 | 3.02 | 0.86 | 1.60 | 2.56 | 4.52 | 0.86 | Improvable |

| R17 | 4.10 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.52 | 3.50 | 0.73 | Acceptable |

| R18 | 5.03 | 2.06 | 1.26 | 1.02 | 2.51 | 1.02 | Good |

| R19 | 2.93 | 1.40 | 1.98 | 2.81 | 4.63 | 1.40 | Improvable |

| R20 | 3.97 | 1.31 | 1.17 | 1.77 | 3.56 | 1.17 | Acceptable |

| R21 | 4.97 | 2.32 | 1.68 | 1.51 | 2.68 | 1.51 | Good |

| R22 | 3.69 | 1.24 | 1.35 | 2.04 | 3.85 | 1.24 | Improvable |

| R23 | 4.75 | 1.75 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 2.79 | 1.01 | Acceptable |

| R24 | 5.73 | 2.83 | 1.94 | 1.26 | 1.89 | 1.26 | Good |

| R25 | 4.43 | 1.91 | 1.52 | 1.72 | 3.19 | 1.52 | Acceptable |

| R26 | 5.46 | 2.54 | 1.67 | 1.12 | 2.11 | 1.12 | Good |

| R27 | 6.47 | 3.63 | 2.70 | 1.86 | 1.41 | 1.41 | Excellent |

5. Results and Interpretation of Inference Maps

Section 4.1 presents the results derived from the application of the agreed-upon AHP method, while Sec. 4.2 details the results of the FIS. Section 4.3, on the other hand, initiates a comparative discussion that evaluates the results of both stages of the methodology based on the implementation objectives of I5.0 by any SME.

5.1. Weights of factors and criteria at local and global levels

Table 13 shows the final weights extracted from the consensus method at each hierarchical level and their overall weighting in the system. The last column indicates the final ranking of the factors and criteria ultimately considered.

| Factors | Criterions | 1st Hierarchy | 2nd Hierarchy | Global | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | Financial sustainability | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.17 | 1 |

| Environmental sustainability | 0.23 | 0.09 | 4 | ||

| Social sustainability | 0.31 | 0.12 | 2 | ||

| Human factor | Employee well-being | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 5 |

| New skills and competencies of human capital | 0.27 | 0.07 | 7 | ||

| Collaboration | 0.39 | 0.10 | 3 | ||

| Resilience | Flexible business processes | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 6 |

| Adaptable production capacity | 0.23 | 0.05 | 9 | ||

| Resilient value chain | 0.23 | 0.05 | 10 | ||

| Technological capacity | 0.18 | 0.04 | 11 | ||

| Anticipation | |||||

| Recovery | |||||

| Organizational strategy | Barriers to the implementation of I5.0 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 13 |

| Enablers for the implementation of I5.0 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 8 | ||

| Transformative business models | 0.22 | 0.03 | 12 | ||

| Innovation outcomes | 0.17 | 0.03 | 14 |

It can be observed that the factors corresponding to the first hierarchy present quite unequal values. Sustainability, with a weight of 0.38, is the factor that tops the list in terms of importance. This is followed by the factors Human Factor and Resilience with weights of 0.25 and 0.21, respectively. Lastly, Organizational Strategy is significantly below the most important factor, with a weight of 0.16.

At the global level, Financial Sustainability (0.17) is by far the criterion with the highest weight, followed by Social Sustainability (0.12). Conversely, the criteria with less importance are Barriers to the Implementation of I5.0, Transformative Business Models and Barriers to the Implementation of I5.0, all with a weight of 0.3.

5.2. Relationship between criteria and inference maps

To verify the coherence of the evaluation system, the analysis of surface maps associated with different FIS of the model is performed using the MATLAB “Fuzzy” Toolbox. Each of these maps illustrates, in height, the value of the output variable of the subsystem to be interpreted, based on two of its input variables (axes), for constant values of the remaining input variables not considered in the map. All axes are illustrated on a scale of [0–10], facilitating comparison and visualization.

5.2.1. Subsystem F1

Figure 10(d) shows the inference map of subsystem F1. The vertical axis represents the output variable Sustainability (F1), and the horizontal axes represent the criteria Social Sustainability (C1) and Environmental Sustainability (C2). The remaining criterion, Financial Sustainability (C3), is set at a constant value of “1”, “5” and “9”, respectively, for each of the inference maps. It can be observed that if the score of Social Sustainability (C1) is too low, F1 would not reach the intermediate value “5” no matter how high the score of the other criteria is. In contrast, when the score of Social Sustainability (C1) is high, the score of F1 is always greater than “5”, regardless of the score of the other criteria (and even greater with higher values of C3 — shift of maps to the right). Furthermore, the behavior is consistent with the weights of importance assigned to each criterion. Thus, since Social Sustainability (C1) has a weight of “0.31”, greater than the weight of Environmental Sustainability (C2) of “0.23”, the growth gradients of F1 are greater in the direction of C1 than in the direction of C2. On the other hand, since Financial Sustainability (C3) has the highest weight of “0.45”, the heights of the maps increase significantly from left to right. The plateaus corresponding to the lowest values of F1 in the maps are usually associated with low values of C1, primarily when C3 has low (left map) or high scores (right map). Once this plateau is overcome, as the input variables increase, the output variable also increases, revealing more pronounced gradients.

However, the criterion most clearly influential in this subsystem would be Financial Sustainability (C3), whose growth always significantly improves the value of the Sustainability factor (F1) and should therefore be the priority improvement objective. Regarding improvement objectives in the other two criteria (C1 and C2), the maps highlight the convenience of simultaneous improvements, as diagonal shifts show greater growth than more lateral ones. Thus, it is important to balance improvement objectives regarding social, environmental and financial aspects in decision-making related to sustainability, in line with the findings of Pasi et al. (2020).

5.2.2. Subsystem F2

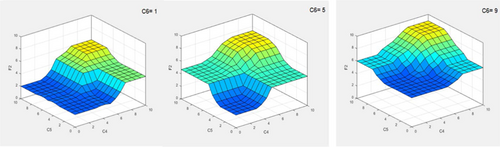

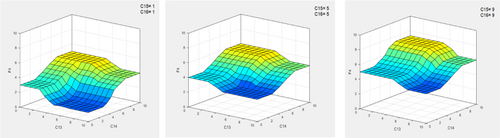

The Human Factor (F2) subsystem depends on three criteria. The three surface maps in Fig. 11 show, horizontally, the criteria: Employee Well-being (C4) with a weight of “0.34” and New Skills and Competencies of Human Capital (C5), with a weight of “0.27” for constant values of “1”, “5” and “9” for the Collaboration criterion (C6) — with a weight of “0.39”.

Fig. 11. Inference maps of subsystem F2 with C6 = 1, C6 = 5, C6 = 9.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The maps illustrate a very similar behavior to the previous case, although when the scores of C6 are very high, the map shows a more symmetrical appearance in its behavior, which is compatible with the fact that the weights of the C4 and C5 criteria are quite close. In this case, it is observed that the priority improvement objective is the Collaboration criterion (C6), as it produces notable increases in the upper plateaus of the maps — from left to right. Furthermore, improvements in the other two criteria (C4 and C5) should also be simultaneous, as the growth gradient diagonally is always higher than laterally. However, in line with (Nayeri et al., 2023), the importance of collaboration is highlighted, as the highest scores in the human factor are achieved when collaboration reaches increasing ratings from “5” to “9” points.

5.2.3. Subsystem F3

The subsystem of the Resilience factor (F3) ultimately depends on four criteria. Of the possible surface maps, Fig. 12 illustrates those corresponding to the two most relevant criteria: Flexible Business Processes (C7) — with a weight of “0.36” — and Adaptable Production Capacity (C8) — with a weight of “0.23” — for constant and equal values of the other two dependent criteria — Resilient Value Chain (C9) and Technological Capacity (C10): C9 = C10, with values of “1”, ”5” and “9” from left to right.

Fig. 12. Inference maps of subsystem F3 with C9 = C10 = 1, C9 = C10 = 5, C9 = C10 = 9.

The behavior of these maps is in all cases quite symmetrical; however, slightly higher lateral gradients are observed in criterion C7 than in C8 (which is also compatible with their assigned weights of importance). In this case, the difference between the central and right maps highlights the limited prevalence of simultaneously increasing the scores of criteria C9 and C10 in the increase of the resilience factor (F3) — e.g. the upper plateau only achieves relative increases of approximately 1 point. Thus, the primary objective, in this case, would be to simultaneously increase the growth of the four criteria dependent on this factor, prioritizing the growth of the Flexible Business Processes criterion (C7), in line with the findings of Rajesh (2021) and Parhi et al. (2022).

5.2.4. Subsystem F4

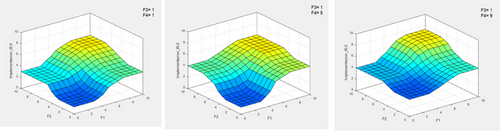

The subsystem of the Organizational Strategy factor (F4) depends on four criteria. In the surface maps illustrated in Fig. 13, we have chosen to present horizontally the criteria corresponding to: Barriers to the Implementation of I5.0 (C13) — with a weight of “0.21” — and Enablers of the Implementation of I5.0 (C14) — with a weight of “0.40” — respectively, for constant and equal values of the other two dependent criteria: Transformative Business Models (C15) and Innovation Results (C16), C15 = C16, with values of “1”, “5” and “9” from left to right.

Fig. 13. Inference maps of subsystem F4 with C15 = C16 = 1, C15 = C16 = 5, C15 = C16 = 9.