Role of Preimplantation Genetic Testing in Indian Women with Advanced Maternal Age to Optimize Reproductive Outcomes

Abstract

Purpose: Does preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) in embryos help women of advanced maternal age (AMA) of Indian origin to achieve better reproductive outcomes?

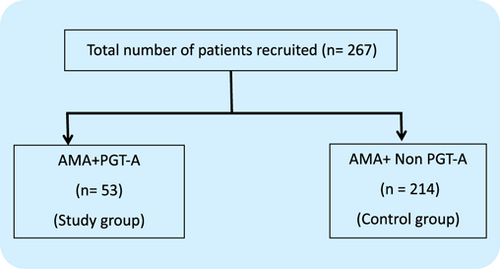

Methods: In this retrospective study, a total of 267 patients were recruited, of which 53 patients (PGT-A group) consented to PGT-A, followed by euploid embryo transfer, whereas the remaining 214 patients (non-PGT-A group) underwent frozen embryo transfer (FET) of unscreened morphologically graded blastocysts.

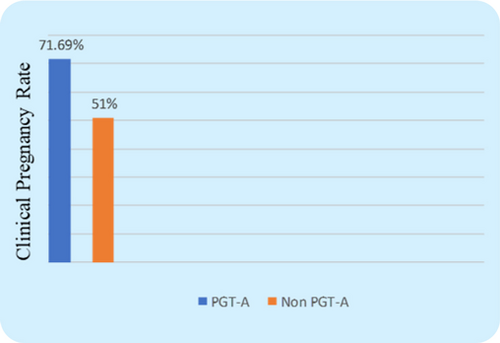

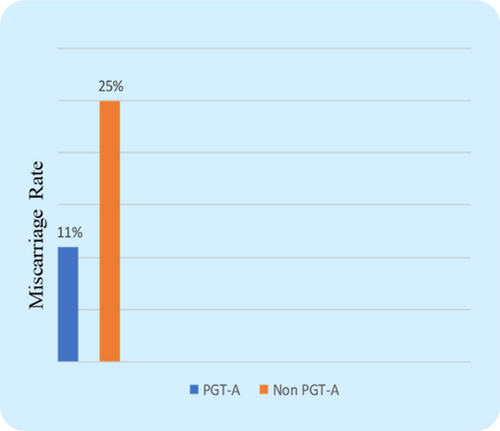

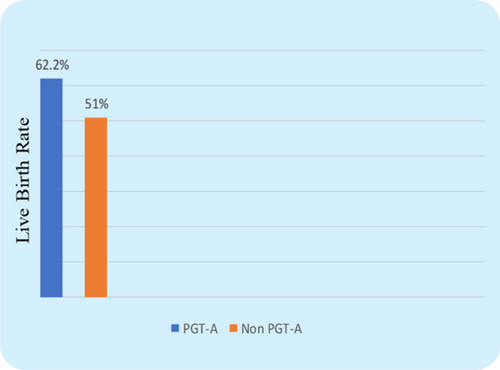

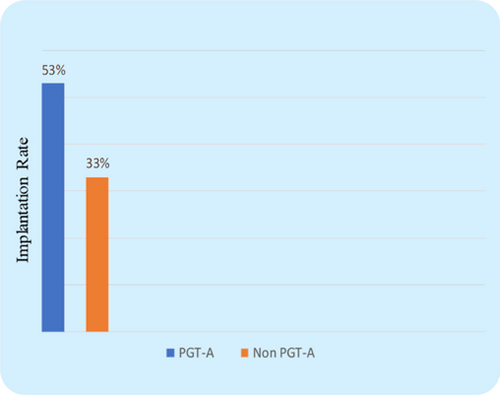

Results: A significant increase in the clinical pregnancy rate was observed in the PGT-A group when compared to the non-PGT-A group (71.6% vs. 51%, P=0.003), while the miscarriage rate was found to be lower in the PGT-A group compared to the non-PGT-A group (11% vs. 25%, P=0.016). The live birth rates were also significantly better in PGT-A group (60.3% vs. 25.6%, P=0.001). In the PGT-A group, similarly, the implantation rate was found to be significantly higher than in the non-PGT-A group (53% vs. 33%, P=0.004).

Conclusions: The data suggest that PGT-A testing in women of AMA can improve their reproductive outcomes. Role of PGT-A seemed equally efficient in women of Indian origin and showed no difference based on ethnicity.

INTRODUCTION

Women’s reproductive potential decreases significantly with advancing age (Devesa et al., 2018); at the age of 35–37, a women’s cumulative pregnancy rate starts to drop and by the time she is 45 years of age, it is less than 10% (Cetinkaya et al., 2013; Tsafrir et al., 2007). Many women today are delaying their motherhood into their late 30s due to their changing lifestyles and career aspirations. This emerging reproductive trend is posing a huge challenge for assisted reproduction centers as many women strongly believe that assisted reproduction techniques (ART) can truly reverse maternal aging (Leridon, 2004; Mills et al., 2011). It is well-established that advanced maternal age (AMA; defined as ≥37 years) is an important variable that greatly reduces the chances of having a healthy live birth even with in vitro fertilization (IVF) (Cimadomo et al., 2018). Women who delay childbirth into their late 30s not only have a lower likelihood of having a live birth, but also have impaired embryo development in vitro (Janny and Menezo, 1996). The greater than or equal to 37-year cut-off is set mainly due to high embryo aneuploidy rates, which drastically increase from a baseline of 30% to 90% in women in their late 30s–40s (Capalbo et al., 2017; Franasiak et al., 2014).

Numerous studies have shown that infertility, miscarriages, and chromosomally abnormal pregnancies are more common among women of AMA (Magnus et al., 2019; Nybo Andersen et al., 2000). Errors in chromosomal segregation resulting in trisomic pregnancies occur much more frequently in women who are approaching the end of their childbearing years (Grande et al., 2012). The higher chances of embryo aneuploidy in AMA women may be due to dwindling ovarian reserve (OR) (Faddy et al., 1992), cohesin dysfunction (Cheng et al., 2017), reduced stringency of spindle assembly checkpoints (Steuerwald et al., 2001), impaired mitochondrial metabolic activity (Van Blerkom, 2011), and shortening of telomeres (de Lange, 2009).

Initially, embryo biopsy was only performed to rule out hereditary genetic disorders and sex chromosome abnormalities in the suspected couples, so as to prevent the genetic condition from passing down to the next generation. However, recently, embryo biopsy and preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is applied for screening embryos with respect to euploid status. Transfer of euploid embryos after PGT-A is thought to improve outcomes of ART cycles. Application of PGT-A for women with AMA to improve reproductive outcomes has been common clinical practice and shown to be beneficial (Rubio et al., 2017; Ubaldi et al., 2019). The use of PGT-A for AMA seems to be rising in Indian clinics. There are not many publications that talk about the reproductive outcomes and efficiency of PGT-A technique in the Indian population. Hence, we wanted to look at the role of PGT-A in these women.

OBJECTIVES

Does PGT-A in embryos help women of AMA of Indian origin to achieve better reproductive outcomes?

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design, size, and duration

This is a retrospective case study from 2014 to 2020 at a private teaching fertility clinic. A total of 53 AMA (Age ≥37 years; Age range: 37–43 years) patients were included in study group (PGT-A). Women with AMA and non-PGT-A intervention were the control group, 214 AMA women (Age ≥37–40 years). In the study group AMA, women who had blastocysts for biopsy and had at least one Euploid Blastocyst for frozen embryo transfer (FET) were recruited for this study. In the control group (non-PGT-A), all embryos were cryopreserved by vitrification and later transfer was done on a frozen embryo replacement transfer cycle, as per the clinic’s policy.

AMA was the sole indication for offering PGT-A for the women recruited in this study. In the control group, women who had two good grade blastocysts who had shown 100% survival post warming were considered and recruited for this study. Blastocyst grading was done as per Istanbul Consensus 2012 (Balaban et al., 2011) and blastocysts which showed an expansion of level 3 and above, Inner Cell Mass (ICM) and Trophectoderm (TE) cells showing level 1 or 2 were considered good grade and were transferred. Women who had poor grade blastocysts or no blastocysts formed were excluded from this study. Only women using their own oocytes were considered in this study. To avoid bias of advanced paternal age, data from couples where male age was less than 45 years only was considered in this study.

STIMULATION AND PATIENT PREPARATION

All the patients were stimulated by following a down regulation stimulation protocol with GnRH antagonist (Gonal F, Merck Global, USA) for 10–12 days from D2/D3 of menstrual cycles to stimulate the ovaries to produce enough follicles. The growth of the Antral follicles was continuously monitored by ultrasound and blood estradiol (E2) levels. The dosage of the stimulation drug was individualized based on patient characteristics. Once the lead follicle reached 18–20mm, trigger injection was administrated (hCG 10,000, Serum Institute, India) and oocyte retrieval was done 35–36 hours post trigger.

All interventions performed during the infertility treatments were in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All couples who opted for PGT underwent counseling session and informed written consent was obtained about the benefits, challenges, and pitfalls of the embryos biopsy technique and the results of PGT. Only couples who gave informed consent were recruited in this retrospective study. A waiver for ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board before proceeding with data publication.

OOCYTE COLLECTION, INSEMINATION, AND EMBRYO DEVELOPMENT

The ovum pick-up (OPU) was done post 35–36 hours of hCG trigger under transvaginal ultrasonography (TVS) with the help of suction pressure. The follicular fluid was screened under a stereo zoom microscope in the IVF laboratory by the embryologist into 60-mm petri dishes. The cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) were separated from the follicular fluid and cultured in fertilization media (Quinn’s advantage protein plus, Cooper Surgical Inc., USA) for 2–3 hours. The COCs were then denuded with enzymatic (Hyaluronidase 80U/mL, Cooper Surgical, USA) and mechanical process. All the metaphase II (MII) oocytes underwent intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). The semen sample was obtained from their partners by masturbation and analyzed for count and motility. Double density gradient was used for sperm processing and morphologically normal sperm were used for injection during ICSI. All MII oocytes were injected and cultured in a single step culture medium until day 5 (Sage 1 step with HSA, Origio, Denmark) at 37∘C in a humidified incubator with hypoxic culture conditions (5% oxygen). Normal fertilization was confirmed by observing two distinct pronuclei and two polar bodies 16–18 hours post-ICSI. The fertilized zygotes were cultured until day 5/6 using standard incubation protocol. The embryo development assessment was done on day 5/6 and grading of the blastocyst was done as per the standard grading system (Balaban et al., 2011).

BIOPSY, TUBING, AND VITRIFICATION

Only grade 1 ad 2 fully expanded blastocysts were selected for biopsies. Number of embryos to be biopsied and consent forms were obtained from the patients. LASER-assisted hatching was performed 4 hours prior to biopsy. This was done to facilitate herniation of enough TE cells and once herniated, the biopsy was performed aspirating six to eight TE cells by using a biopsy needle (Blastomere aspiration needle, Cook, USA). Aspirated TE cells were then transferred into a PCR tube that contained phosphate buffer saline (PBS) provided by the genetic lab (Igenomix, India) carefully in the presence of an eye witness. The biopsied cells were then stored in a deep freezer at −21∘C until they were shipped to the genetic laboratory. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) was the method used for PGT in this study.

The collapsed blastocysts were further cultured for a period of 1–2 hours post biopsy for their expansion and then vitrified using a Kitazato vitrification kit (Kitazato BioPharma, Tokyo, Japan) and stored on a cryotop in liquid nitrogen (LN2).

FROZEN EMBRYO TRANSFER

For subsequent FET, the endometrium was prepared by giving estrogen support. Once the endometrium attained adequate thickness (>8mm), luteal phase support was started, and FET was planned. On the day of transfer, the thawing of one/two PGT-A euploid embryos was done by using the Kitazato Thawing kit (Kitazato BioPharma, Tokyo, Japan). The thawed blastocyst was cultured for 2 hours for survival confirmation in one-step culture medium at 37∘C. One or two thawed blastocysts were transferred into the uterus by using an ET catheter (Emtrac set, Gynetics, Belgium). Fourteen days after ET, the patient underwent a urine pregnancy test and pregnancy was confirmed by Beta hCG levels in the blood (>50mIU/mL).

Following were the outcomes measured between the study and control populations:

Clinical Pregnancy Rate (CPR) defined as number of gestational sacs with presence of fetal cardiac activity (numerator) per number of embryo transfer cycles done (Denominator).

Statistics

Considering the small sample size and unequal group size, Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate the statistical significance of the outcomes measured. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. (Statistical calculation done using https://www.medcalc.org/calc/fisher.php)

Results

A total of 267 patients were included as per the inclusion criteria. Out of the 267 patients, 53 patients had undergone biopsy followed by euploid blastocyst transfer were grouped as PGT-A (n=53, Study group) and the rest of the patients, where the blastocyst transfer was done, entirely based on the morphological analysis of the embryo were grouped as non-PGT-A (n=214, Control group). The study group includes patients with AMA+PGT-A and the control group refers to patients with AMA+non-PGT-A (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow chart representing the patient recruitment into the groups.

The CPR was found to be considerably higher in the PGT-A group (71.6% vs. 51%, P=0.003) (Fig. 2), which indicates that transferring a PGT-A selected euploid embryo can increase the overall pregnancy outcome in the IVF cycle for women with AMA. Further, the miscarriage rate (MR) was found significantly lower in the PGT-A group as compared to the non-PGT-A group (11.3% vs. 25.4%, P=0.016) (Fig. 3), which demonstrates that PGT-A may detect most of the chromosomal anomalies (Structural and Numerical chromosomal disorders) responsible for early miscarriages. There was significant difference observed in terms of live birth rate (LBR) between the groups—PGT-A versus non-PGT-A (60.3% vs. 25.6%, P=0.001) (Fig. 4). The PGT-A group also had a significantly higher overall implantation rate (IR) (53% vs. 33%, P=0.004) (Fig. 5), which demonstrates that transferring a PGT-A selected euploid embryo increases its chances of implantation and live birth.

Fig. 2. Comparison of Clinical Pregnancy Rate (CPR) between the control group & test group patients. The clinical pregnancy rate between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.007).

Fig. 3. Comparison of miscarriage rate (MR) between the control group & test group patients. The Miscarriage rate between the two groups showed statistical significance (P=0.02).

Fig. 4. Comparison of Live Birth Rate (LBR) between control group & test group patients. The live birth rate between the two groups was not statistically significant (P=0.14).

Fig. 5. Comparison of Implantation rate (IR) between the control group & test group patients. The implantation rate between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.007).

Discussion

The primary objective of PGT-A in ART is to select the most competent embryo for transfer, after analyzing its genetic makeover or genotype, thus improving the reproductive outcome.

Our study showed a significant increase in CPR, implantation rate (IR), LBR, and a lower MR in AMA women who had undergone PGT-A when compared to AMA women without PGT-A (Table 1). A lot of studies have emphasized the use of PGT-A in the AMA group of patients and elaborated on the benefits of selecting a euploid embryo for transfer (Lee et al., 2015; Rubio et al., 2017; Sacchi et al., 2019; Ubaldi et al., 2019). One such study by Lee et al. (2015) has demonstrated that blastocyst biopsy is a reliable method for detecting euploid embryos for transfer and supported the use of PGT-A in AMA patients (2015). Findings from this study also supports the inference of the earlier publications. In another study, it was concluded that testing embryos for common chromosomal aberrations using PGT-A resulted in fewer embryo transfers, lower miscarriages, and increased pregnancy rates in AMA patients (Sacchi et al., 2019). In his recent study, Ubaldi et al. has emphasized the significance of TE biopsy, vitrification, and Comprehensive Chromosomal Screening (CCS) for single embryo transfer in AMA patients (Rubio et al., 2017; Ubaldi et al., 2019).

| S1. No. | Variables | Non-PGT-A | PGT-A | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of FET | 214 | 53 | ||

| 1. | Clinical Pregnancy Rate (CPR) | 51 % | 71.6 % | 0.003 |

| (109/214) | (38/53) | |||

| 2. | Miscarriage Rate (MR) | 25.4 % | 11.3 % | 0.016 |

| (54/214) | (6/53) | |||

| 3. | Implantation Rate (IR) | 33 % | 53 % | 0.004 |

| (141/428) | (45/85) | |||

| 4. | Live Birth Rate (LBR) | 25.6 % | 60.3 % | 0.001 |

| (55/214) | (32/53) |

Recurrent miscarriage (RM) is a multifactorial disorder defined by two or more losses. Hodes-Wertz et al. (2012) found that idiopathic RM is mostly caused by aneuploid embryos and that PGT-A could decrease MR and improve PR. IVF/PGT-A appears to lower the miscarriage risk when compared with natural conception. Data from our study also showed a similar trend of a lower MR with the use of PGT-A and transfer of a euploid embryo.

However, there are few studies comparing the LBR in AMA patients followed by TE biopsy and euploid embryo transfer. In this regard, Lee et al. (2015) have supported that the application of TE biopsy and PGT-A could improve the LBR in women aged 40–43 years. Most studies have looked at IRs and MRs, very few studies looked at LBRs and our study also looked at LBR as one of the end outcomes. Data from our study has also shown a similar trend of optimized reproductive outcomes as published in the literature previously. The ultimate goal of ART treatment is to achieve a healthy live birth. To accomplish this goal, we need a tool to select the euploid embryos from the cohort to minimize the risk of transferring aneuploid embryos. PGT-A can be a helpful tool for selecting chromosomally competent embryos for transfer in the ART cycle, especially in the AMA group of patients where the rate of chromosomal anomalies is higher. Also, transferring one PGT-A-selected euploid embryos can lower the multiple gestational pregnancies and can avoid the health risks associated with it to the mother (Meldrum, 2013). The use of PGT-A in AMA patients can reduce the time taken for conceiving.

Additionally, this study wanted to look at the role of PGT-A for AMA specifically in an Indian population. Most studies published so far are from Caucasian populations and we wanted to see if there is a difference in outcomes based on ethnicity. Nevertheless, we noticed similar and comparable outcomes in Indian women when compared with the Caucasian women. Irrespective of the ethnicity, advancing age seems to alter the ploidy status and PGT-A is an active intervention, which can help enhance the reproductive outcomes for couples seeking fertility treatments. Globally, there seems to be a trend to postpone childbearing and advancing age is an obstacle to have a successful outcome. Interventions like PGT-A not only help choose euploid embryos, which in turn helps in optimizing reproductive outcomes, but it also helps to reduce the time to conception.

However, PGT-A has its own limitations, such as it is an invasive technique as it requires TE biopsies to be performed on blastocysts, also the cost of testing each blastocyst is expensive.

Moreover, many AMA women have a poor OR, which limits the number of blastocysts available for testing, thereby further reducing the chances of having at least one euploid embryo for transfer from the cohort. In such cases, the patient may end up with no blastocyst for transfer in the IVF cycle and needs to go for another cycle. Due to these factors, the use of PGT-A for advanced age women in the ART cycle on a routine basis is debatable. The assessment of necessity and counseling of patients is of utmost priority.

In the future, there seems a need for safer, robust, and user-friendly interventions for AMA women to help enhance success rates and also have minimal deviation from the physiological process.

CONFOUNDING FACTORS

Although this study is supporting the role of PGT-A in women with AMA to optimize the reproductive outcomes, there are few confounding factors. This is a retrospective observational study with unequal size and small sample size. This study did not consider looking at differences in reproductive outcomes between days 5 and 6 stage blastocysts. In the study group (PGT-A group), women had one or two euploid blastocysts transferred versus the control group had two unscreened blastocysts transferred. Although the role of PGT-A in women with AMA seems re-assuring, there still seems a need for a well-designed randomized multicenter trials to further test the efficacy.

CONCLUSIONS

Data from this study showed PGT-A to be useful in women of AMA, where transferring a single euploid embryo aided with better reproductive outcomes when compared to, transferring a blastocyst based on its morphological characteristic alone. As mentioned, PGT-A has its own limitations but at present, seems like it is the only efficient strategy available to minimize the age-related reproductive risk in AMA women. Current study showed a similar efficacy of PGT-A cycles in AMA women of Indian origin. There seemed no difference based on ethnicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the staff and laboratory personnel at our Fertility Unit for their generous support and assistance throughout this study. Authors would also want to thank all the health workers who were involved in the care for the patients.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare. Interventions performed as a part of this retrospective study have relevant informed patient consents duly signed.

ORCID

Krishnachaitanya Mantravadi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7642-6743

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7642-6743

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technology |

| PGT | Preimplantation Genetic Testing |

| AMA | Advanced Maternal Age |

| CCS | Comprehensive Chromosomal Screening |

CONTRIBUTION DETAILS

| Role (Concepts, Design, and Definition of intellectual content, investigation, manuscript writing, etc.) | Contributor 1 | Contributor 2 | Contributor 3 | Contributor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript Writing | Dr. Beena | Dr. Krishna Chaitanya | ||

| Concept, design | Dr. Krishna Chaitanya | Dr. Durga G Rao | Ms. Pooja Chauhan | |

| Definition of intellectual content, investigation | Dr. Durga G. Rao | Dr. Krishna Chaitanya | ||

| Statistical analysis | Ms. Beena Rawat |

ETHICAL POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

This is a retrospective observational study with prior consents from patients enrolled. Institutional review board was approached for a waiver of ethical clearance and an approval was obtained. Copy of the letter attached with this submission.

PATIENT DECLARATION OF CONSENT STATEMENT

Consents have been obtained for all patients prior to the procedures.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data of this study is available on request to the author.

REPORTING GUIDELINES

This manuscript adheres to STROBE reporting guidelines.

Reporting guidelines for Original Research Articles (Case control, Cohort, and Cross-Sectional studies): STROBE (2007).

| Item No | Recommendation | Yes/No | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract. | Yes |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found. Structured abstract: Aims and Objectives, Materials and Methods, Results, Conclusion.Format to be consistent. | Yes | ||

| Introduction | |||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported. | Yes |

| Objectives | 3a | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses. The research objective should not be biased. | Yes |

| 3b | Statements to be appropriately cited | Yes | |

| Methods—Structured methods section (with subheadings) is preferred | |||

| Study design | 4a | Present key elements of study design early in the paper (cross sectional/cohort/case-control) | Yes |

| 4b | Is the study design robust and well-justified? | Yes | |

| Setting | 5a | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | Yes |

| 5b | Mention the details of the supplier/manufacturer of the equipment/materials (e.g., Chemicals) used in the study | Yes | |

| 5c | Mention the details of the drugs (manufacturer, dosage, dilution, frequency, and route of administration, monitoring equipment) used in the study | Yes | |

| 5d | Mention the details about the cell lines (names and where it was obtained from) | NA | |

| 5e | Mention the details of plant sample collection (Location, time period, validation of the specimen, Institution where the specimen is submitted, and the voucher specimen number) | NA | |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Cohort study—Give the eligibility criteria (inclusion/exclusion), and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up. | Yes |

| Case-control study—Give the eligibility criteria (inclusion/exclusion), and the sources and methods of case ascertainment and control selection. Give the rationale for the choice of cases and controls. | NA | ||

| Cross-sectional study—Give the eligibility criteria (inclusion/exclusion), and the sources and methods of selection of participants. | NA | ||

| (b) Cohort study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed. | NA | ||

| Case-control study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and the number of controls per case. | NA | ||

| Variables | 7a | Clearly define all outcomes (primary and secondary), exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. | Yes |

| 7b | Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable. | Yes | |

| Data sources/measurement | 8* | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group. | Yes |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | Yes |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size (sample size) was arrived at. | NA |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why. | NA |

| Statistical methods(a separate heading needed) | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding. | Yes |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions. | NA | ||

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed. | NA | ||

| (d) Cohort study—If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed.Case-control study—If applicable, explain how matching of cases and controls was addressed.Cross-sectional study—If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy | NA | ||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses. | |||

| Results | |||

| Participants | 13* | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—for example, numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed | NA |

| (b) Give reasons for nonparticipation at each stage. | NA | ||

| (c) Consider the use of a flow diagram. | NA | ||

| Descriptive data | 14* | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, and social) and information on exposures and potential confounders. | Yes |

| (b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest. | NA | ||

| (c) Cohort study—Summarize the follow-up time (e.g., average and total amount). | NA | ||

| Outcome data | 15* | Cohort study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time. | NA |

| Case-control study—Report numbers in each exposure category, or summary measures of exposure. | NA | ||

| Cross-sectional study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures. | NA | ||

| Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included. | Yes |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized. | NA | ||

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period. | NA | ||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses done—for example, analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses. | NA |

| Presentation | 18a | Tables and graphs properly depicted with no repetition of the data in the text | Yes |

| 18b | Annotation/footnotes to be mentioned appropriately | Yes | |

| 18c | Abbreviations to be defined in the footnotes | Yes | |

| Discussion | |||

| Key results | 19 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives. | Yes |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias. | Yes |

| Interpretation | 21 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence. | Yes |

| Generalizability | 22 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results. | Yes |

| Citations | 23a | The statements should be adequately cited. | Yes |

| 23b | Recent citations (last 5 years) to be cited in a greater proportion. | Yes | |

| Other information | |||

| Funding | 24a | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based. | Yes |

| 24b | Mention the Grant Number. | NA | |

| Ethical approval and Patient consent | 25a | Mention the IRB approval and the approval number (for animal and human subjects). | NA |

| 25b | Mention if the study has been conducted in accordance with the ethical principles mentioned in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) | Yes | |

| 25c | Mention if the patients have consented to participate in the study.To mention if consent has been waived/exempted by IRB | Yes | |

| Conflict of interest | 26 | Mention the financial, commercial, legal, or professional relationship of the author (or the author’s employer) with sponsors/organizations that could potentially influence the research. | Yes |

| Language | 27 | The language should be understandable without grammatical errors that hinders the readability. | Yes |