Precise Localization for Anatomo-Physiological Hallmarks of the Cervical Spine by Using Neural Memory Ordinary Differential Equation

Abstract

In the evaluation of cervical spine disorders, precise positioning of anatomo-physiological hallmarks is fundamental for calculating diverse measurement metrics. Despite the fact that deep learning has achieved impressive results in the field of keypoint localization, there are still many limitations when facing medical image. First, these methods often encounter limitations when faced with the inherent variability in cervical spine datasets, arising from imaging factors. Second, predicting keypoints for only 4% of the entire X-ray image surface area poses a significant challenge. To tackle these issues, we propose a deep neural network architecture, NF-DEKR, specifically tailored for predicting keypoints in cervical spine physiological anatomy. Leveraging neural memory ordinary differential equation with its distinctive memory learning separation and convergence to a singular global attractor characteristic, our design effectively mitigates inherent data variability. Simultaneously, we introduce a Multi-Resolution Focus module to preprocess feature maps before entering the disentangled regression branch and the heatmap branch. Employing a differentiated strategy for feature maps of varying scales, this approach yields more accurate predictions of densely localized keypoints. We construct a medical dataset, SCUSpineXray, comprising X-ray images annotated by orthopedic specialists and conduct similar experiments on the publicly available UWSpineCT dataset. Experimental results demonstrate that compared to the baseline DEKR network, our proposed method enhances average precision by 2% to 3%, accompanied by a marginal increase in model parameters and the floating-point operations (FLOPs). The code (https://github.com/Zhxyi/NF-DEKR) is available.

1. Introduction

The cervical spine is the smallest, most mobile, and highly active segment of the human spinal column, characterized by its complex anatomical structure. Cervical spine diseases are common and challenging conditions in the field of neurosurgery, characterized by symptoms like neck pain, neurological impairments, and related spinal cord or nerve root issues.

X-rays are more widely used than CT or MRI for screening spinal disorders, primarily due to their convenience, speed, relatively inexpensive, and ability to image bones clearly. In the early stages of screening, assistant physicians are usually the first to view the images, and they usually assess the condition intuitively by looking at the severe deformities or injuries of the bones on the images. There is a lack of accurate measurement metrics to support this, as well as limitations on the efficiency of manual assessment. Based on this fact, screening technologies that accurately locate anatomo-physiological hallmarks and artificial intelligence are essential to support the screening process for mid-level medical staff, providing timely recommendations for adjunctive diagnosis and management, thus speeding up the patient care process and improving medical efficiency.

Neural network technologies1,2,3 have made significant progress in the field of medical imaging4,5,6,7 and disease detection8,9,10 in recent years. These techniques can automatically extract image features and perform precise classification5,11 and segmentation,12,13 providing faster and more objective preliminary diagnostic results for physicians. Several deep learning architectures14,15,16 have been proposed for keypoint detection. DeepPose17 was introduced in 2014, utilized the AlexNet18 backbone network to extract image features and regression models to obtain accurate keypoint locations in the human body. Subsequent methods, such as Hourglass19 and Simple Baseline,20 have further improved the performance by incorporating high-resolution feature maps. In 2019, the HRNet21 adopted a parallel connection network structure, maintained the highest resolution feature map in the entire process, and fused features of different scales, which is of great significance for keypoint detection. However, in real world scenarios, the issue of blurred vertebral contours is common in any medical image used for the cervical spine. In addition, X-ray images usually have low contrast, and the irregularity of the vertebrae hampers the labelling and inferential prediction of the data to some extent, resulting in the data showing unavoidable variability. At the same time, the cervical spine occupies a relatively small portion of the entire image, and predictive localization of anatomo-physiological hallmarks for vertebrae of the cervical spine requires the simultaneous prediction of 20 densely distributed keypoints, further complicates the task of accurate keypoint prediction on cervical spine bodies.

To solve the above problems, we designed a Disentangled Keypoint Regression (DEKR) network that integrates Neural Memory Ordinary Differential Equation and Multi-Resolution Focus, termed as NF-DEKR. The unique global attractor property of Neural Memory Ordinary Differential Equations (nmODEs)22,23 enables us to effectively address the variability problem associated with blurred vertebral contours and the difficulty in precisely locating the four corner points of the vertebral body. nmODE establishes complex temporal dynamics models in X-ray images to identify potential motion blur or other dynamic changes occurring during patient imaging. Furthermore, through nmODE, we can explore the nonlinear features of X-ray images, thereby enhancing the ability to recognize subtle structures and anomalies within the images. Building upon this, we devised the Multi-Resolution Focus (MRF) module to differentiate the treatment of feature maps at various scales, enabling more accurate localization of cervical spine keypoints in cervical X-ray images characterized by large images and small parts. In contrast to the traditional model of attention computation, we compress and extract features from all scales generated by the backbone, perform fusion learning, and then diverge attention scores through affine transformation, instead of confining them to (0,1). NF-DEKR accurately identifies and measures the 20 keypoints of C2–C7 cervical spine through the analysis of cervical X-ray images. By comparing the positions and distances of these keypoints with normal reference values, we can rapidly assess the patient’s cervical spine health status, assisting physicians in making accurate diagnoses.

We firmly believe that the introduction of an automated precise localization method for anatomical features of the cervical spine can improve diagnostic efficiency and accuracy, ease the workload of medical professionals, and provide patients with better healthcare services. We evaluated the network’s performance on a dataset from a tertiary hospital in Western China and on a publicly available CT dataset. Especially, NF-DEKR is validated on multimodal data, such as X-rays from different devices and CT scans. However, regardless of the type of medical imaging data used for the cervical spine, the issue of vertebral ambiguity persists. In summary, this study’s primary contributions are as follows:

| (1) | We design a deep neural network architecture NF-DEKR for prediction of keypoints in cervical physiological anatomy, and introduce the idea of nmODE on the basis of each submolecule in the Disentangled Regression branch of DEKR. By utilizing its characteristics of separating memory and learning and converging to a unique global attractor, the variability of the data was effectively solved. | ||||

| (2) | We introduce the MRF module to further enhance accuracy in predicting densely localized keypoint tasks, strategically processing feature maps of different scales before entering the decoupled regression branch and heatmap branch. | ||||

| (3) | We construct a medical dataset SCUSpineXray of 723 cervical spine X-ray images, aged 18–40 years, annotated by orthopedic specialists. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first dataset dedicated specifically to cervical spine C2–C7 anatomo-physiological hallmarks. The dataset size surpasses previously available public datasets, further enhancing its reliability. | ||||

2. Related Work

In this section, we retrospectively examine three key components pertaining to our approach: neural ordinary differential equations (ODEs), attention mechanism and multi-resolution networks.

2.1. Neural ordinary differential equation

The emergence of neural ODEs24 has enabled the representation of discrete finite layers in deep neural networks as approximations of continuous-time ODEs. This natural correspondence allows models to implicitly map inputs to outputs. Dupont et al.25 enhanced neural ODE models by introducing auxiliary variables, thereby improving the model’s capacity for nonlinear modeling and enhancing its expressiveness. Building upon this progress, Chen et al.26 extended neural ODEs to implicitly define termination times, enabling modeling of discrete events in continuous-time systems. In this work, we adopt the nmODE framework proposed by Yi.23 Distinguished from other neural ODEs, nmODE exhibits superior nonlinear modeling capabilities while maintaining a simpler structure and clearer dynamic characteristics. Specifically, nmODE separates memory neurons from learning neurons, making it robust to medical images.27 Notably, nmODE possesses the property of global attractors, ensuring convergence to a fixed state regardless of external input. Furthermore, incorporating external input variables as nmODE’s input data overcomes many issues related to learning and input data space homeomorphism encountered in traditional neural ODEs.

2.2. Attention mechanism

In the fields of computer vision and natural language processing, attention mechanisms play a vital role in processing large-scale input data and selectively focusing on relevant information. The concept of attention mechanisms originated from the workings of the human visual system, where the brain efficiently filters out relevant information from the environment. Bahdanau et al.28 first introduced attention mechanisms and applied them to machine translation tasks, which have since been widely used in sequence-to-sequence models. Hu et al.29 proposed channel-wise feature recalibration achieved through squeeze-and-excitation operations to calibrate features along the channel direction. Su et al.30 argued that attention mechanisms are applied in both channel and spatial directions, dynamically adjusting the weights of different channels and modeling long-range spatial dependencies, resulting in significant improvements in multi-person pose estimation. The above-mentioned methods focus solely on spatial and channel attention for single-layer feature maps. To explore multi-layer feature maps of different scales, Xiao et al.31 extends the spatial attention mechanism to multiple hierarchical features, allowing adaptive assembly of different-scale features, which are then applied to the Hourglass model. However, it neglects the characteristic of traditional attention decay. In our approach, to maximize the utilization of feature information, we compress and normalize feature maps generated at various scales by the backbone. Common normalization functions such as softmax or sigmoid restrict weights to a range less than 1, resulting in weakened weighted feature intensities.32,33 To address this traditional issue of attention feature attenuation, we employ an affine transformation to scale the weights to any desired range.

2.3. Multi-resolution network

In keypoint localization tasks, feature maps of different resolutions play distinct roles. High-resolution feature maps are advantageous for precise spatial localization of keypoints, while low-resolution feature maps provide rich global contextual information, particularly useful for inferring keypoints in ambiguous structures and occluded regions. Multi-resolution networks have been widely used in semantic segmentation tasks, with architectures like SegNet34 and U-Net35 using upsampling to recover high-resolution feature maps from low-resolution ones. However, this upsampling process inevitably leads to some loss of feature information. In 2019, HRNet21 was introduced, which maintains high-resolution feature maps throughout the entire network while ensuring that feature information is preserved. Moreover, HRNet enables numerous interactions between high-resolution and low-resolution feature maps. Our study combines MRF module and HRNet as the backbone of the network. Compared to traditional encoder–decoder35,36,37 structures, our multi-resolution network reduces information loss, preserves more spatial details, and achieves better feature fusion. MRF provides HRNet with the learning capability in the final stage of feature fusion, enabling it to differentiate and handle features at different scales, rather than simply performing channel concatenation.

3. Method

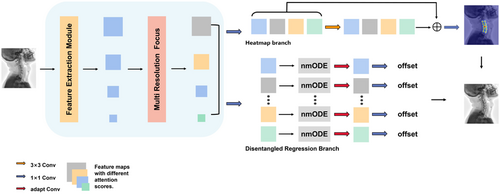

We employ the DEKR network38 as the base architecture, with the high-resolution network HRNet serving as the backbone. We incorporate the MRF module, followed by the heatmap branch and the disentangled regression branch, where the nmODE is integrated. Through this approach, we achieved significant results in the task of predicting the anatomo-physiological hallmarks of the cervical spine.

3.1. Overview

We adopt the HRNet as the backbone of our architecture. HRNet is a deep neural network architecture, designed to address high-resolution image processing challenges in computer vision. Its primary objective is to provide multi-scale, multi-resolution information exchange while preserving high-resolution features, thus enhancing the modeling capacity for image details and spatial structures. The HRNet’s network structure comprises multiple stages, each containing one or more high-resolution sub-networks. Each sub-network has its own convolutional and upsampling layers, responsible for feature reconstruction from low-resolution to high-resolution. An example of the network is as follows :

Moreover, HRNet incorporates a feature fusion module for information exchange and feature fusion among different resolution features, facilitating collaboration between multi-scale features, an example of the fusion module is as follows :

HRNet’s notable advantage lies in its ability to effectively handle high-resolution images while retaining the richness of image details and spatial structures. Compared to traditional downsampling operations, HRNet better preserves fine-grained details when dealing with high-resolution images.

After the backbone, four feature maps of different scales are obtained. Through the MRF module, we assign different weights to these feature maps. In the parallel multiple branches of the keypoint regression prediction head, we integrate the nmODE module, where each branch corresponds to a specific keypoint. By introducing adaptive convolution, we learn the unique features for each keypoint, achieving decoupled regression prediction for all keypoints. The network schematic is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The entire network NF-DEKR. After passing the MRF module, we apply transform and concat operations to the feature maps. Subsequently, the transformed feature maps are separately fed into the disentangled regression branch (displaying only four parallel sub-branches, while there are 20 sub-branches in the actual task) and the heatmap branch.

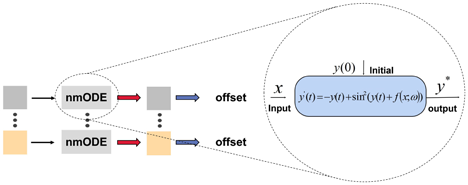

3.2. The nmODE module

In practice, head profile X-ray images often present challenges in predicting the keypoints of the cervical spine due to low contrast and blurred contours of the cervical spine site. In the meantime, defining the exact position of the four corner points is a subjective task for locating the physiological anatomy of the cervical spine, leading to certain inconsistencies during annotation. The annotated keypoint positions in the dataset may exhibit inevitable variability, which can impact subsequent training and performance evaluation of algorithms and models relying on these keypoints. To overcome this problem, we introduce the nmODE module, which is considered as an insertion module for deep neural networks. The nmODE has clear dynamics compared to traditional deep neural networks, giving more powerful nonlinear modeling capabilities to the model.

The nmODE can be abstracted as the following equation :

Leveraging this property, we introduce nmODE to the disentangled regression branch module, which is inscribed in the following equation. For each pixel xj(1≤j≤m) on the feature map, using nmODE in the component form, there are

By this means, we establish a well-defined nonlinear mapping from external inputs to their corresponding global attractors without introducing external parameters.

The nonlinear mapping is of vital importance for keypoint detection tasks, as it captures complex spatial transformations, enabling the algorithm to locate and identify keypoints accurately. By leveraging implicit differential equation, the nmODE module increases the nonlinearity of the network. As a result, the robustness and generalization ability of the keypoint detection algorithm can be improved.

As mentioned above, the variability of keypoint annotation brings challenges to the training and performance of detecting algorithms. The reason behind this problem is that the traditional algorithms are inherently discrete. A small or a slight deviation may lead to a large error in the results. Conversely, the attractor introduced by nmODE is essentially continuous, which eliminates the errors caused by artificial annotations.

Furthermore, nmODE exhibits a certain corrective effect on features. As depicted in Fig. 2, we incorporate nmODE into the disentangled regression branch’s adaptive convolutional learning sub-branch for each keypoint. The objective is to use nmODE to adjust the individual keypoint’s feature map before adaptive learning of its coordinate offset, thereby achieving more accurate results.

Fig. 2. Intuitive illustration of nmODE.

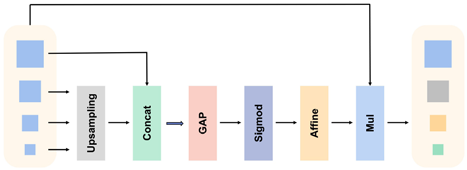

3.3. Multi-resolution focus module

In keypoint detection networks, high-resolution low-level features are crucial for predicting precise spatial positions, while high-level features with large receptive fields play a significant role in reasoning about some invisible keypoints. However, in DEKR, in the last stage of the backbone, the fusion of multi-scale features is performed merely through channel-level concatenation, which is not a learnable process. Feature maps at different scales play different roles in head networks.39,40 We were inspired by attention mechanisms and multi-resolution networks to design the MRF module, which introduce learnable individual weight values for each scale of feature maps, enabling the regression prediction head to treat different scales of feature maps differently. Specifically, to overcome the problem of attentional decay, we propose to use the affine transformations to make its attention score no longer limited to (0,1). The overall process of the module is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. MRF module.

We segment the multi-scale attention module into two distinct steps: the scale-aware feature extraction stage and the scale-sensitive excitation stage.

In the scale-aware feature extraction stage, we start by uniformly compressing the channel dimensions of four feature maps {χCR}4={χC11,χC22,χC33,χC44} with different scales using 1×1 convolution. This transformation aligns the feature maps from different scales into the same feature space, facilitating easier fusion and integration of information. The feature maps are then upsampled to the same resolution in order to ensure that features at all scales are spatially aligned so that the model can effectively capture multi-scale information, and a preliminary feature fusion representation is obtained by simple concatenation, which is finally sent to a convolution operation to compress the number of channels to four. The calculation can be represented as follows :

During the scale-sensitive excitation stage, we first obtain the feature representation vectors at the channel scale by global average pooling the results from the compression stage. Each dimension of the vector represents a global feature calculation operator corresponding to the scale feature map. These feature vectors are converted to the attention mappings corresponding to each scale by sigmoid function. To counteract the attention decay caused by the sigmoid function, and to ensure that attention weights are not limited, an affine transformation is applied to obtain the final multi-scale feature vectors. These vectors are ultimately multiplied with the corresponding feature maps to produce the final output. The calculation process can be expressed as follows :

Finally, the response is applied to four different scales of feature maps Final by performing element-wise multiplication, resulting in the attention maps. The calculation method can be represented as follows :

4. Experiments

In this section, we provide a comprehensive description of the dataset and experimental setup used to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. We conducted ablation experiments to assess the efficacy of each module within our proposed method, and compared it against state-of-the-art keypoint detection methods to demonstrate the feasibility of our approach.

4.1. Dataset

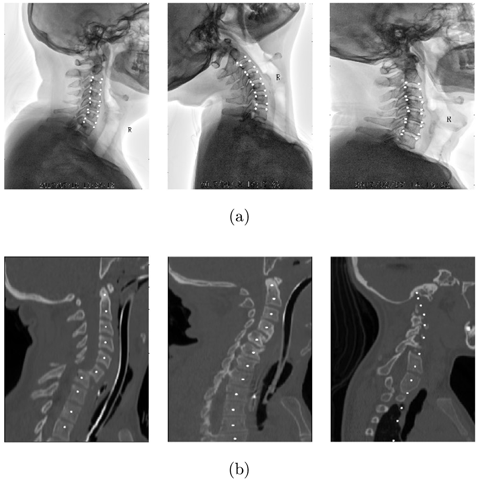

SCUSpineXray. This dataseta was obtained from cervical spine X-ray images collected by the Department of Orthopedics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China. The X-ray images in the dataset were acquired using various instruments, such as X-ray machines, computed tomography scanners, and fluoroscopic devices. The dataset encompassed a total of 983 patients who visited our department for orthopedic consultations between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2021. The patients’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 years old. Due to incomplete X-ray images or unforeseen circumstances during examinations, 36 patients were excluded, and some data got corrupted during the transmission process. Ultimately, a total of 723 cases were available for analysis. To ensure the reliability of the annotation information, all X-ray data used in this dataset were annotated by professional orthopedic doctors and verified by senior physicians. The doctors annotated a total of 20 coordinate points for each case on the X-ray images, as shown in Fig. 4(a). Specifically, they marked four corner points for each cervical spine (C3 to C6), as well as the lower and upper surface corner points for C2 and C7. To provide accurate validation results, the dataset was partitioned into training, and test sets in an 8:2 ratio, ensuring that examination images acquired from three different devices were evenly distributed between the training and validation sets.

Fig. 4. Examples of data and labels. (a) SCUSpineXray, the four corner points of the vertebrae are labeled. (b) UWSpineCT, public dataset annotated with the center points of the vertebrae.

UWSpineCT. The dataset consists of focused (i.e. tightly cropped) CT scans of the spine from 125 patients with different pathology types.41 For most patients, multiple scans from the longitudinal examination were available, resulting in a total of 242 scans in the database. Each scan image has manually labeled vertebral centroids. These data were obtained from the University of Washington Radiology Department. We selected data with C1-T2 vertebral center points for a total training set of 81 cases, as shown in Fig. 4(b), and 10 slices were taken for each CT at a certain step size. The final whole dataset contains 810 training images and 190 test images.

4.2. Experimental setup

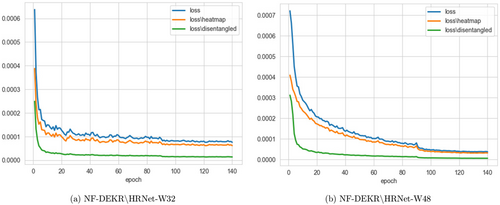

During the training phase, we perform affine transformations on the images to resize them to a dimension of 512×512. To enhance the model’s performance and generalization ability, we employ a series of data augmentation techniques, including random translations in the X and Y directions. The translation range is set to [−0.2Width,0.2Width] and [−0.2Height,0.2Height] to introduce variability in the dataset and promote robustness in the model’s learning process. We apply random scaling of the images by a factor of [0.75,1.5] and random rotation by an angle of [−30∘,30∘] to introduce further variability into the dataset. The Adam optimizer42 is employed, with a base learning rate of 1e−3, it is reduced to 1e−4 and 1e−5 at the 90th and 120th epochs, correspondingly. The training concludes upon reaching the 140th epoch, as shown in Fig. 5. For training, we use a batch size of 2 and implement the entire method using PyTorch43 2.0.1 and Python 3.10.11. All methods and experiments were conducted on a system running the Windows operating system with two NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPUs.

Fig. 5. The training loss of NF-DEKR with different backbones.

During the evaluation phase, we adopt the average precision (AP) based on Object Keypoint Similarity (OKS) as the evaluation metric. OKS measures the algorithm’s accuracy by comparing the estimated keypoint locations to the ground truth keypoint positions. This approach provides a robust evaluation of the model’s performance in keypoint detection. The calculation formula of OKS is shown in the following equation :

4.3. Component ablation studies

4.3.1. The position of nmODE

In order to explore the optimal position of nmODE in the model, we conducted experiments in the heatmap branch and the disentangled regression branch of the head network, respectively. The experiments were conducted on the SCUSpineXray dataset, and the results are shown in Table 1. The results show that the nmODE module can better reflect its memory-learning separation characteristics in the disentangled regression branch.

| Heatmap branch | Disentangled regression branch | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone | With nmODE | Without nmODE | With nmODE | Without nmODE | AP±Std (%) |

| HRNet-W32 | ✓ | ✓ | 93.11±1.94 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 92.21±1.63 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 94.49±0.46 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 93.68±0.84 | |||

We analyze that the heatmap branch is designed to generate a probability distribution map for keypoints, representing the likely positions of the keypoints in the image, it is localized and discrete. This branch is typically used to detect the presence of objects and provides confidence estimates for the locations of keypoints. On the other hand, the nmODE branch is more focused on describing changes in dynamic systems. From Eq. (4), it is evident that nmODE pays more attention to global information, aiding the regression branch in capturing dynamic information or spatial changes in the object. This provides additional contextual information for keypoint localization tasks, enabling the model to better understand the shape, posture, or position of the object. The heatmap branch generates pixel-level activation maps to highlight local features, while the disentangled regression branch predicts continuous coordinates, capturing global patterns in feature variations. nmODE excels in modeling variable changes, ensuring stable outputs with reduced noise effects. However, its continuous dynamic modeling doesn’t notably benefit the discrete, localized activations targeted by the heatmap branch.

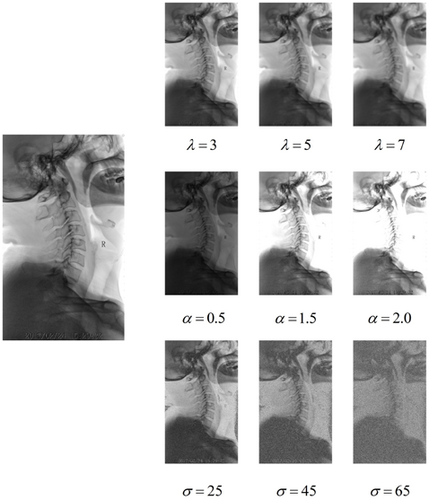

4.3.2. The role of nmODE

To verify the significant role of nmODE in addressing the inherent variability of the SCUSpineXray dataset, we designed the following experiments to simulate challenges such as insufficient illumination or exposure conditions encountered during X-ray imaging, blurred vertebral contours in imaging, and noise problems caused by low radiation doses. We applied three different enhancements to the training set: Gaussian blur, luminance enhancement, and Gaussian noise. Specifically, for Gaussian blurring, we tried different standard deviations (λ=3,5,7), the purpose of the blurring operation is to smooth the image details and reduce the sharpness of the image to achieve a specific visual effect. For Gaussian noise, we applied noise levels with mean 0 and different standard deviations (σ=25,45,65). For luminance enhancement, we applied different levels of enhancement operations (α=0.5,1.5,2.0) as shown in Fig. 6. The purpose of these enhancement operations is to simulate different visual environments in a real scene and to evaluate their impact on the image processing task. The experimental results are shown in Table 2, and it can be seen that nmODE performs well in the face of different types of data with different degrees of variability, thanks to the fact that nmODE has one and only one global attractor y∗. Given any external inputs, nmODE defines a good nonlinear mapping from the external input x to the attractor y∗.

Fig. 6. Example of data variation. There are Gaussian blurs with different standard deviations, λ=3,5,7. Gaussian noise with a mean of 0 with different standard deviations, σ=25,45,65, and different degrees of brightness enhancement, α=0.5,1.5,2.0.

| AP±Std (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | DEKR38 | nmODE | |

| Blur | λ=3 | 91.85±1.67 | 93.11±2.20 |

| λ=5 | 90.67±2.07 | 92.72±1.64 | |

| λ=7 | 61.01±1.02 | 82.68±1.11 | |

| Noise | σ=25 | 93.20±2.63 | 94.52±1.82 |

| σ=45 | 91.81±2.69 | 93.86±2.37 | |

| σ=65 | 91.01±1.18 | 93.23±0.92 | |

| Bright | α=0.5 | 91.04±2.32 | 93.30±1.09 |

| α=1.5 | 93.66±1.94 | 94.33±2.08 | |

| α=2.0 | 94.23±0.90 | 94.39±0.89 | |

4.3.3. The nmODE and MRF

In this section, we investigated the effectiveness of nmODE and MRF on the baseline network. We compared the baseline network DEKR38 with the versions where nmODE, MRF, and both nmODE and MRF were added, the experiments were conducted on the SCUSpineXray dataset and results are shown in Table 3. Based on the results of the ablation experiments, we draw the following conclusions: First, the addition of the nmODE module significantly improved the network’s performance, confirming its effectiveness. The introduction of this module enhanced the network’s nonlinear modeling capability and positively influenced the correction of the feature maps fed into the offset branch, thereby improving the overall performance metrics. Furthermore, we explored the impact of nmODE on model parameters and floating-point operations (FLOPs). We found that incorporating the nmODE module did not introduce additional network parameters, but marginal increase in computational complexity. Through carefully designed structures and parameters, the nmODE module augments the network’s representational capacity and task processing capabilities without the need for additional parameters. This finding further supports the effectiveness and feasibility of the nmODE module for practical applications. Second, the addition of the MRF module also had a positive impact on the network’s performance, further enhancing its performance on the given task. Finally, when both nmODE and MRF modules were added simultaneously, the network’s performance further improved with only a slight increase in model parameters and FLOPs. This indicates that these two modules have complementary effects and can work synergistically to enhance the model’s performance.

| Approach | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | AP±Std (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-DEKR without nmODE and MRF | 29.679 | 8.440 | 93.11±1.94 |

| NF-DEKR without MRF | 29.679 | 8.462 | 95.05±1.15 |

| NF-DEKR without nmODE | 29.696 | 8.456 | 94.99±0.46 |

| NF-DEKR (Ours) | 29.696 | 8.478 | 95.59±0.48 |

4.4. Comparative experiment

To assess the validity of our proposed approach, we performed experiments on the SCUSpineXray and UWSpineCT datasets, conducting comparisons with the state-of-the-art pose estimation methods, including DEKR38 and RLE44 (regression-based methods), as well as HRNet,21 CID,45 HRFormer,46 and ViTPose47 (heatmap-based methods). The experimental results, as shown in Table 4, demonstrate that our method achieved an AP±Std (%) of 95.59±0.48, surpassing previous accuracies in localization for anatomo-physiological hallmarks on X-ray images. Compared to the baseline model DEKR on SCUSpineXray dataset, a hypothesis test was conducted. The results indicate that our method achieved a significant improvement in AP compared to DEKR (t-statistic: t≈−2.95, p-value: p≈0.015). Despite a slight increase in model parameters and FLOPs, this improvement is statistically significant, demonstrating clear advantages of our method on the SCUSpineXray dataset. This finding indicates that the nmODE and MRF modules work complementarily, enhancing the model’s accuracy and meeting clinical demands effectively. Moreover, our method, utilizing a small network (HRNet W32) with a channel size of 32 as the backbone, outperformed DEKR even when it uses HRNet W48 as the backbone. This improvement can be attributed to the powerful nonlinear modeling capability brought by the nmODE module and its positive effect on feature map refinement. Additionally, the MRF module’s unequal treatment of multi-scale feature maps in the heatmap branch and decoupled regression branch also plays a positive role. Overall, our proposed method demonstrates superior performance compared to previous mainstream methods, showcasing the advantages of the nmODE and MRF modules in achieving remarkable accuracy.

| Dataset | Model | Backbone | Input size | Params | FLOPs | AP±Std (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCUSpineXray | Heatmap | |||||

| HRNet | HRNet-W32 | 256×192 | 28.536M | 7.686G | 94.17±1.25 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 256×192 | 63.596M | 15.746G | 95.04±0.70 | ||

| CID | HRNet-W32 | 512×512 | 29.365M | 8.111G | 94.73±0.67 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 512×512 | 65.450M | 16.624G | 94.38±1.10 | ||

| HRFormer | HRFormer-B | 256×192 | 43.212M | 14.264G | 95.32±0.76 | |

| ViTPose | ViT-H | 256×192 | 0.637G | 0.126T | 95.00±0.62 | |

| Regression | ||||||

| DEKR | HRNet-W32 | 512×512 | 29.679M | 8.440G | 93.11±1.94 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 640×640 | 65.814M | 16.964G | 94.61±1.42 | ||

| RLE | ResNet152 | 384×288 | 58.362M | 11.321G | 93.17±1.44 | |

| Ours | HRNet-W32 | 512×512 | 29.696M | 8.478G | 95.59±0.48 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 640×640 | 65.850M | 17.015G | 95.82±0.82 | ||

| UWSpineCT | Heatmap | |||||

| HRNet | HRNet-W32 | 256×192 | 28.536M | 7.686G | 91.43±2.39 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 256×192 | 63.596M | 15.746G | 92.05±1.79 | ||

| CID | HRNet-W32 | 512×512 | 29.365M | 8.111G | 91.35±1.07 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 512×512 | 65.450M | 16.624G | 91.65±2.47 | ||

| HRFormer | HRFormer-B | 256×192 | 43.212M | 14.264G | 92.15±1.31 | |

| ViTPose | ViT-H | 256×192 | 0.637G | 0.126T | 88.23±2.42 | |

| Regression | ||||||

| DEKR | HRNet-W32 | 512×512 | 29.679M | 8.440G | 93.08±2.71 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 640×640 | 65.814M | 16.964G | 94.53±2.00 | ||

| RLE | ResNet152 | 384×288 | 58.362M | 11.321G | 89.37±1.34 | |

| Ours | HRNet-W32 | 512×512 | 29.696M | 8.478G | 93.95±0.92 | |

| HRNet-W48 | 640×640 | 65.850M | 17.015G | 95.15±1.02 | ||

4.5. Visualization

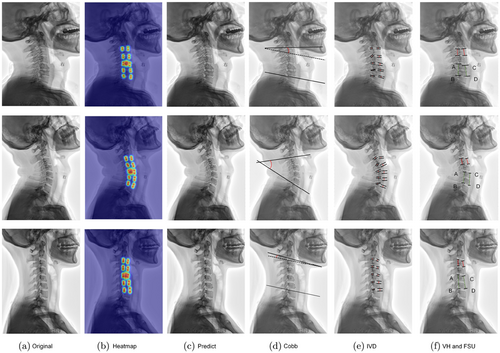

Figure 7 shows the prediction results of three randomly selected X-rays from our test set of SCUSpineXray. Where (a) is the original image, (b) is the heatmap predicted by the network, and (c) is the final output of the network. We also calculated (d) cobb angle, (e) intervertebral space distance, (f) vertebral body height and FSU based on the predicted coordinates of the points. By quantifying these metrics, it helps doctors to make a quick and accurate identification on an outpatient basis to determine whether there is an alteration of cervical physiological curvature or even a severe cervical retroversion, and also facilitates radiological assessment for postoperative follow-up. At the same time, through these quantitative indicators, doctors can also have an accurate understanding of the intervertebral height and vertebral body morphology, which is conducive to determining whether disc degeneration or vertebral body changes have occurred in the relevant segments, and can assist doctors in making further clinical decisions.

Fig. 7. (Color online) (a) Original X-ray image. (b) Heatmap. (c) Network output. (d) To calculate the cobb angle, two points on the lower surface of C2 and two points on the upper surface of C7 are selected, and the angle between them is the cobb angle. (e) Intervertebral distance. (f) Calculation of vertebral height and FSU. Where red is the vertebral height calculation using the C3 vertebrae as an example, the calculation alone does not require the calculation of the average value; green is the C5/6 FSU height as an example, FSU=AB+CD2, AB indicates the posterior height of the two adjacent vertebrae and CD indicates the anterior height.

In addition, thanks to the time-saving and labor-saving feature of automated measurement, doctors can apply the model to a large number of radiographic images accumulated in the clinic over a long period of time, and establish a large clinical database of these indicators, which is very meaningful for the research of related diseases, especially at the epidemiological level.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a deep neural network architecture NF-DEKR for prediction of keypoints in cervical physiological anatomy. We introduce a MRF module that employs differentiated strategies for feature maps of different scales. Moreover, we integrate the nmODE into the disentangled regression branch, benefiting from its unique global attractor properties and powerful nonlinear modeling capabilities. This helps combat the inherent variability in the dataset and effectively refines the feature maps fed into each sub-branch of the disentangled Regression branch. The results of ablation experiments validate the effectiveness of our modules. Our method achieves optimal performance with an AP±Std(%) of 95.59±0.48, outperforming the baseline model DEKR (with HRNet-W32 as the backbone) with only a slight increase in model parameters and FLOPs, resulting in a 2.48% improvement in AP. This further satisfies the high accuracy requirements in clinical diagnostics. While the NF-DEKR model performs well in predicting keypoints in cervical physiological anatomy, it may not be sensitive to certain physiological changes such as tumors, inflammation, or structural abnormalities. To further improve the model’s accuracy and robustness, we plan to optimize the model architecture and expand the dataset in the future.

ORCID

Xi Zheng  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7850-643X

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7850-643X

Yi Yang  https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1626-4530

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1626-4530

Dehan Li  https://orcid.org/0009-0001-8298-4888

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-8298-4888

Yi Deng  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8584-5624

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8584-5624

Yuexiong Xie  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3282-2998

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3282-2998

Zhang Yi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5867-9322

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5867-9322

Litai Ma  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8168-8108

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8168-8108

Lei Xu  https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5297-7046

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5297-7046

Notes

a For academic research needs, contact us by email.