DO CIRCUIT BREAKERS IMPEDE TRADING BEHAVIOR? A STUDY IN CHINESE FINANCIAL MARKET

Abstract

As the most influential regulation in 2016, China launched circuit breakers in the financial markets. However, the circuit breaker mechanism was implemented for only four days and then suspended. Many criticisms then stated that circuit breakers impeded trading behavior in Chinese financial markets. This study explores this short-life circuit breaker mechanism in China, and examines whether circuit breakers impede trading behavior in Chinese financial markets as many criticisms stated. We use an intraday dataset and investigate the circuit breakers. Contrary to those criticisms, we find that circuit breakers are not easily reachable and have no “magnet effect” between two thresholds of breakers. We also find that without protection of circuit breakers, potential large market fluctuations will have negative impacts on individual stocks’ liquidity and value. As the major contribution, our study indicates that Chinese financial markets still need a circuit breaker mechanism to protect investors’ benefits and maintain the market liquidity and stability.

1. Introduction

Circuit breaker is an automatically trading suspension mechanism that many financial trading venues use to decrease price volatility. The mechanism literally sets a ceiling and a floor for the price to move within a trading day. When the price moves in either direction and reaches the threshold, venues will halt trading for a short period or suspend trading for the whole day. In December 2015, China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) issued the first circuit breaker regulation including two threshold levels, 5% and 7%, in both directions. When the benchmark index, China Securities 300 Stocks Index (CSI 300), rises or falls by 5% of the closing price of the previous trading day, the stock trading will halt for 15 min; when CSI 300 rises or falls by up to 7%, a full breaker will run and the market will shut down for the whole day.

This circuit breaker regulation was officially launched on January 4th, the first trading day of 2016. However, the thresholds of circuit breakers were soon touched in the following trading days. On January 4th, CSI 300 fell by 5% at 1:12 pm and led to a 15 min halt; it then proceeded down to 7% at 1:33 pm, and incurred a full break till the market closing time. Due to the two breaker cases, Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) had a loss of RMB 1,900 billion yuan, about 6.86% of its market capitalization. The crash at Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) was even worse. The loss reached up to RMB 2,000 billion yuan, about 8.20% of the overall market capitalization. This loss of markets became the largest daily crash during the last four months. On January 7th, thresholds were triggered again at the 5% level at 9:42 am and at the 7% level at 9:58 am. The market had to shut down after opening for only half an hour. On January 8th, CSRC announced to suspend the circuit breaker mechanism.

The objective of this paper is to explore this short-life circuit breaker mechanism in China, and examine whether circuit breakers impede trading behavior in Chinese financial markets. We first collect, review and sort the criticisms about the circuit breaker mechanism. After the suspension of circuit breakers, many immediate follow-up articles criticize the short-life circuit breaker mechanism and summarize its glitch into three types of criticisms. First, the thresholds of circuit breakers are set too low and easy to be triggered (Li, 2016; Yang, 2016). Second, the thresholds of circuit breakers are too close to each other, and may generate the “magnet effect” to accelerate the market to reach threshold level II after passing level I (Gao and Yang, 2016; Liu, 2016; Xu and Lu, 2016; Yang, 2016). Third, this circuit breaker mechanism prevents the market liquidity and pricing discovery for investors’ trading (Pi, 2015; Wang, 2016; Zhu, 2016).

We then examine whether the circuit breaker mechanism behaves as these criticisms stated, by using an intraday dataset of stock trading. Through the examination, this paper answers a critical question: should Chinese financial markets abandon this elaborately planned circuit breaker mechanism? It is also the major contribution of this paper. This research question can be further transferred to another practical question: does the failure of this circuit breaker mechanism attribute to the three problems described in the three types of criticisms above?

To investigate the three types of criticisms, respectively, we observe the performance of both the overall stock market and individual stocks. We use the intraday data and observe the whole year 2015. The data during this selected observation period were previously used to design, test and debug the circuit breakers by Chinese trading venues (SSE, 2015). Our findings correspond to the three types of criticisms with respective empirical tests. First, our results indicate that the possible cases to trigger circuit breakers count only 2% of the trading time in one year, which does not support the opinion about easily reachable breakers. Second, we test the “magnet effect” between two thresholds of breakers, and find no evidence that the market will have a higher probability to touch threshold level II after reaching level I. Third, we investigate individual stocks and find that without circuit breakers, large market fluctuations have negative impacts on individual stocks from diverse aspects. In conclusion, our results do not support the three types of criticisms. It shows that Chinese financial markets still need a circuit breaker mechanism like foreign markets, to protect investors’ benefits and maintain the market liquidity and stability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature and the historical background of the circuit breaker mechanism in China and foreign countries. Section 3 lists three hypotheses about the impact of circuit breakers on Chinese markets and examines them. Section 4 concludes.

2. A Review of Circuit Breaker

On October 19th, 1987, the “Black Monday” crash began in the American stock market and the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) lost over 20%. In order to lower the potential market volatility and illiquidity, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) approved the circuit breaker mechanism in trading venues of equities and derivatives. In 1988, the New York Security Exchange (NYSE) implemented the first circuit breaker program. Following NYSE, similar programs were implemented in a number of other countries so as to prevent extreme price volatility. The 2008 report issued by World Federation of Exchanges (WFE) investigated 40 trading venues and found that 24 of them had applied circuit breakers, as described in Table 1. Almost all the large and influential trading venues in developed countries have circuit breaker mechanisms, suggesting that circuit breakers become a widely used instrument in the global markets.

| With Circuit Breakers | Without Circuit Breakers | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Athens Exchange | Amman Stock Exchange |

| 2 | BME | Australian Securities Exchange |

| 3 | Bolsa de Comercio de Buenos Aires | Bermuda Stock Exchange |

| 4 | Bolsa de Valores de Colombia | Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago |

| 5 | Bourse de Luxembourg | Bolsa Mexicana de Valores |

| 6 | Bourse de Montréal | Colombo Stock Exchange |

| 7 | Chicago Board Options Exchange | Cyprus Stock Exchange |

| 8 | Deutsche Börse AG | Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing |

| 9 | Indonesia Stock Exchange | IntercontinentalExchange ICE |

| 10 | Irish Stock Exchange | International Securities Exchange - ISE |

| 11 | Korea Exchange | Istanbul Stock Exchange |

| 12 | Ljubljana Stock exchange | Jasdaq Securities Exchange, Inc. |

| 13 | The NASDAQ Stock Market | JSE Limited |

| 14 | NASDAQ OMX (Stockholm) | Shanghai Stock Exchange |

| 15 | National Stock Exchange of India Ltd. | Stock Exchange of Tehran |

| 16 | Osaka Securities Exchange Co., Ltd. | Taiwan Stock Exchange (TWSE) |

| 17 | Olso Bors ASA | |

| 18 | Singapore Exchange Ltd. | |

| 19 | SIX Swiss Exchange | |

| 20 | Stock Exchange of Thailand | |

| 21 | Tel Aviv Stock Exchange | |

| 22 | Tokyo Stock Exchange Group, Inc. | |

| 23 | TMX Group | |

| 24 | Wiener Börse AG |

Circuit breakers gain more attention as the policy tool to protect the capital and confidence of investors in the era of increased automated high-frequency trading (Subrahmanyam, 2013), though studies have confirmed the automated trading has no threat to regular investors’ capital gains (Li et al., 2018) or market liquidity (Li, 2018a).

Although Chinese stock markets had applied price limits on individual stocks since 1996, they did not have any market-level circuit breakers. But a series of studies have explored the design and feasibility of circuit breaker mechanisms in the Chinese markets and supported the implementation (Shi, 1996; Shen and Wu, 1999; Guotai Junan Securities, 2001; Sun and Shi, 2001; Mu et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2003; Su and Mai, 2004; Li, 2005; Du, 2006; Liu et al., 2006). For example, Shi (1996) observed the market fluctuations of SSE since SSE was founded in 1990, and found 18 times of market fluctuations over 15%. He therefore pointed out the necessity of a circuit breaker mechanism in Chinese stock markets. As one of the largest Chinese investment institutions, Guotai Junan Securities (2001) released a report to summarize the circuit breaker mechanisms in the international markets, and introduced analytical methods to examine the effectiveness of circuit breakers. Wu et al. (2003) studied the influence of price limits and found no evidence to prove that price limits may accelerate the price fluctuations afterwards. Du (2006) conducted a test on Chinese stocks and stated that a circuit breaker is necessary for stocks with low market values. Some other studies (Meng and Jiang, 2008; Li et al., 2009; Chen and Ge, 2010; Jiao and Sun, 2010; Zhang, 2015; Gui, 2016) also confirm that circuit breakers are needed in the Chinese markets.

A series of recent trading incidents accelerate the launching of circuit breakers in Chinese financial markets. For example, on August 16th, 2013, due to the trading error by its automated trading program, Everbright Securities, one of the largest securities brokerages in China, placed accidental buy orders for exchanged-traded funds and resulted in inflated orders totaling 23.4 billion yuan at SSE. SSE Index experienced sharp intraday volatility and the abnormal increase reached up to 5.96% in 1 min. Everbright’s August glitch initiated the discussion of China Regulator about the setting of circuit breakers. During June and August, 2015, a crash occurred in stock markets. As the extreme case, SSE Index fell by 35% in several days. The information-driven markets react to such news fiercely, as proved by recent studies (Li, 2018b). To maintain the market stability, SSE, SZSE and China Financial Futures Exchange (CFFEX) announced jointly that they were studying a circuit breaker mechanism and implemented soon. According to CSRC, a circuit breaker mechanism can “cool down” the market trading and avoid the occurrence of large abnormal fluctuations in financial markets.

Many studies consider the circuit breaker as an efficient instrument in financial markets (Gerety and Mulherin, 1992; Kleidon and Whaley, 1992; Lauterbach and Uri, 1993; Subrahmanyam, 1994). Harris (1998, 2003) studied circuit breakers in different countries and summarized five characteristics: trading halts, price limits, transaction taxes, margin requirements and collars. Tooma (2005) showed that most studies on circuit breakers focused on trading halts and price limit. Greenwald and Stein (1991) found that trading halts could help these value-motivated investors better read the market, and thereby improve market quality. Subrahmanyam (1994) provided a theoretical model and stated that trading halts could intensify price movements and increase volatility because investors fear that a trading halt may impede their order execution. Ackert et al. (2000) used an experimental method to analyze the impact of circuit breakers on price dynamics, trading volume, and profit-making ability. Brugler and Linton (2014) studied London Stock Exchange (LSE) and confirmed the function of circuit breakers on promoting market-wide stability. Additionally, Lee et al. (1994), Santoni and Liu (1993), Overdahl and McMillan (1997), Goldstein et al. (2000) also confirmed the effectiveness and contribution of circuit breakers. Therefore, circuit breakers should be a positive resolution to risk management in the financial markets of China.

There are very few studies discussing circuit breakers in Chinese financial markets after 2018. Chen et al. (2019) confirmed the importance of price limits on individual stock trading and pointed out that 41 out of 58 major countries have applied price limit rules in their equity exchanges. Another paper by Chen et al. (2017) constructed a theoretical model to investigate how circuit breakers impact the market when investors trade to share risk. As an extension of these studies, this paper constructs an empirical study using the intraday data, and investigates the market-wide circuit breaker instead of individual stocks’ price limits. It brings new findings from different angles.

3. Analysis of Circuit Breakers in China

In this section, we start to examine circuit breakers in Chinese market from different aspects. To be in line with the circuit breaker mechanism, we take CSI 300 as the target index.

CSI 300 is a capitalization-weighted stock market index and composed of 300 stocks with the largest market capitalization and liquidity from SSE and SZSE. It was launched on April 8, 2005, by the China Securities Index Company, the largest leading index provider in China. According to research reports issued by Hong Kong Stock Exchange (2017) and China Securities Index Company (2018), it is the first stock market index cooperatively compiled by the two Mainland China stock exchanges.

According to an official document issued by SZSE (2016), CSI 300 has two distinctions in comparison with other indexes. First, CSI 300 measures performance of listed A share companies in both SSE and SZSE, while other indexes mainly reflect the operating condition of a sole market. Second, CSI 300 has advantages in the coverage of market capitalization, the number and asset size of products when it compares with the peers (e.g., CSI 500). It is more representative to measure the entire universe of the Chinese stock market. Thus, with the guidance of CSRC, the Chinese exchanges chose CSI 300 as the benchmark index to initiate the circuit breaker mechanism.

Taking CSI 300 as the object, we summarize three types of opinions from existing articles and hence test the three corresponding hypotheses as follows:

H1: the thresholds of circuit breakers (±5% and ±7%) are too low and they are so easy to be triggered. | |||||

H2: the thresholds of circuit breakers are too close to each other, and therefore generate the “magnet effect” to accelerate the market to reach Threshold Level II (±7%) after passing Level I (±5%). | |||||

H3: this circuit breaker mechanism impedes the market liquidity and pricing discovery. | |||||

3.1. Test on H1

We first examine H1. We use the intraday data of the quotes of CSI 300, the benchmark index of the circuit breaker mechanism. The data is minute-stamped, provided by Wind Financial Database, and covers trading periods during the whole Year 2015. Following the calculation rule of Chinese market circuit breakers, for each minute t in the trading hours of Year 2015, we calculate the percentage change of CSI 300 from its closing price of the previous trading day. We define LstChgt as the percentage change of CSI 300 at Minute t, and compare this percentage change with the thresholds ±5% and ±7%. Our purpose is to observe the frequency of passing the thresholds in Year 2015, and assess whether the cases of passing thresholds are frequent. If it is frequent, it suggests that thresholds are low and easy to be triggered.

Table 2 presents the time periods during which the percentage change of CSI 300 passes thresholds of circuit breakers, and their lengths (counted in minutes), and the average percentage change. There are a total of 33 qualified time periods that passed thresholds in Year 2015. Twenty five of them have negative percentage changes and pass negative thresholds, while only eight have positive percentage changes and pass positive thresholds. Figure 1 depicts the movement of percentage changes. The overall trading time in 2015 includes about 60,000min, whereas the total length of the 33 time periods is 1,767min, which only count 2% of the overall trading time. The results indicate that thresholds of circuit breakers are not so easy to be passed, and consequently do not support H1.

Figure 1. The Percentage Change of CSI 300 in 2015

| Date | Percentage Change (%) | Start | End | Time Length (Minute) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015–01–19 | −6.08 | 09:30 | 09:45 | 15 |

| 2015–01–19 | −7.03 | 13:13 | 15:00 | 107 |

| 2015–05–28 | −5.04 | 14:46 | 15:00 | 14 |

| 2015–06–04 | −5.26 | 13:05 | 13:20 | 15 |

| 2015–06–19 | −5.08 | 14:41 | 14:56 | 15 |

| 2015–06–26 | −5.11 | 11:24 | 13:09 | 15 |

| 2015–06–26 | −7.06 | 14:05 | 15:00 | 55 |

| 2015–06–29 | −5.26 | 13:02 | 13:17 | 15 |

| 2015–06–29 | −7.16 | 13:14 | 15:00 | 106 |

| 2015–06–30 | 5.24 | 13:52 | 14:07 | 15 |

| 2015–07–01 | −5.01 | 14:48 | 15:00 | 12 |

| 2015–07–02 | −5.40 | 14:13 | 14:28 | 15 |

| 2015–07–03 | −5.29 | 10:05 | 10:20 | 15 |

| 2015–07–03 | −7.03 | 10:24 | 15:00 | 186 |

| 2015–07–06 | 8.55 | 09:30 | 15:00 | 240 |

| 2015–07–07 | −5.11 | 10:54 | 11:09 | 15 |

| 2015–07–08 | −7.05 | 09:30 | 15:00 | 240 |

| 2015–07–09 | 5.07 | 13:13 | 13:28 | 15 |

| 2015–07–09 | 7.06 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 60 |

| 2015–07–10 | 5.10 | 09:43 | 09:58 | 15 |

| 2015–07–10 | 7.00 | 10:44 | 15:00 | 166 |

| 2015–07–15 | −5.09 | 13:38 | 13:53 | 15 |

| 2015–07–27 | −5.06 | 14:19 | 14:34 | 15 |

| 2015–07–27 | −7.00 | 14:35 | 15:00 | 25 |

| 2015–08–18 | −5.24 | 14:40 | 14:55 | 15 |

| 2015–08–24 | −5.27 | 09:35 | 09:50 | 15 |

| 2015–08–24 | −7.09 | 09:50 | 15:00 | 220 |

| 2015–08–25 | −5.10 | 13:29 | 13:44 | 15 |

| 2015–08–25 | −7.03 | 14:24 | 15:00 | 36 |

| 2015–08–27 | 5.11 | 14:42 | 14:57 | 15 |

| 2015–09–01 | −5.03 | 10:09 | 10:24 | 15 |

| 2015–09–16 | 5.14 | 14:42 | 14:57 | 15 |

| 2015–11–27 | −5.08 | 14:14 | 14:29 | 15 |

3.2. Test on H2

Next, we examine H2, whether there exists the “magnet effect” to accelerate the market to reach Threshold Level II after passing Level I. We continue using the minute-level dataset of CSI 300 in 2015 and analyze LstChgt, the percentage change of CSI 300 at Minute t. We use the Auto-regression (AR) method by Cho et al. (2003) to examine the magnet effect. We define two dummy variables, D(fiveup)t and D(fivedown)t, to examine whether the percentage change of CSI 300 will move forward to the second threshold (±7%) after reaching the first threshold (±5%) at minute t. The dummy variables are defined in (1).

In Equation (2), γ1 captures the magnet effect of the case of increase. A positive γ1 implies that the percentage change of CSI 300 continues increasing as it rises 5%. Similarly, γ2 captures the magnet effect of the case of decrease. A negative γ2 implies that the percentage change of CSI 300 continues decreasing as it falls 5%. The positive γ1 and the negative γ2 represent magnet effects and are of the most interest of this study.

We first run the AR(3) model for the whole year of 2015. We also pick up days that include the 33 breaker-reached time periods, as a subsample to run the AR(3) model. Table 3 presents the regression results of the AR(3) model for the full length and the sample period. In the analysis of the whole year, the coefficients of γ1 and γ2 are 0.0021 and –9.84E–05, which are far smaller than coefficients of the three lag variables of LstChg. In the analysis of the selected periods including the 33 passing threshold cases, the coefficients of γ1 and γ2 are still very small (0.0034 and 0.0055) and not comparable to coefficients of other variables. In both results, γ1 and γ2 are not statistically significant. The results show that when the fluctuation of the market index reaches the first threshold level of circuit breakers (±5%), there is no incidence for the market to move on to the second threshold level (±7%). Therefore, we do not find any evidence to support H2.

| The Overall 2015 | Trading Days that Include the 33 Breaker-Reached Time Periods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | t-Stat | Coefficient | t-Stat |

| Intercept | 4.02E-05 | 0.12 | −0.0039 | −1.48 |

| LstChgt−1 | 1.7362*** | 443.66 | 1.65*** | 132.15 |

| LstChgt−2 | −1.0138*** | −146.25 | −0.8916*** | −41.01 |

| LstChgt−3 | 0.2772*** | 71.24 | 0.2417*** | 19.53 |

| D(fiveup)t−1 | 0.0021 | 0.53 | 0.0034 | 0.34 |

| D(fivedown)t−1 | −9.84E–05 | −0.03 | 0.0055 | 0.75 |

| Observation | 57,337 | 5,664 | ||

| R2 | 0.9981 | 0.9983 | ||

3.3. Test on H3

In this section, we examine the impact of circuit breakers on market liquidity and pricing discovery. As CSRC’s primary motivation, to launch circuit breakers is to reduce and control the extreme abnormal fluctuation in financial markets, and consequently protect investors’ benefits. In general, investors are more interested in individual stocks that they purchased than the performance of the overall market. Therefore, in order to evaluate the effectiveness of circuit breakers on protection for investors, we should examine their impact from aspects of individual stocks.

Since the circuit breaker mechanism was implemented for only four days, we do not have adequate data to directly analyze the impact of circuit breaker. As an alternative resolution, we take the 33 breaker-reached time periods in 2015 as the study objects. If the liquidity and values of individual stocks become worse during these periods, the circuit breaker mechanism will be proved as a necessary instrument in Chinese financial markets.

We take 100 constituent stocks from CSI 300 as the sample. The dataset is from iFinD Financial Database, and provides trading performance measures for individual stocks, including average price, price change, return and turnover rate. All the measures update by minute. We define two dummy variables, D(circuit up)t and D(circuit down)t, to tell whether CSI 300 rise or fall to the thresholds of circuit breakers at minute t. The dummy variables are defined in (3).

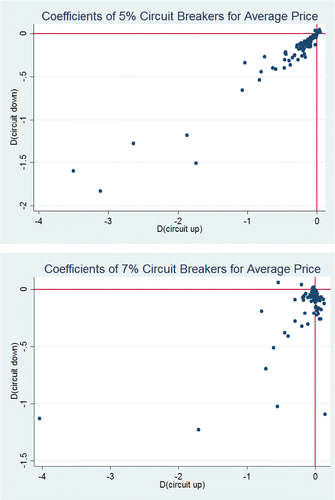

First, we take the average price as DV, run the AR(3) model in (4), and get (b1, b2) for each stock. To graphically display how the circuit breakers affect stock price, we make a scatter plot of the pairs of (b1, b2) for the 100 stocks. Figure 2 depicts the effects of circuit breakers on average prices of stocks. b1 and b2 are coordinate axes of the plots. There are 100 dots in Figure 2, and they represent the 100 stocks. As we explained above, if the over-threshold market fluctuation has positive effects on average prices, the corresponding (b1, b2) should be both positive and the dot should be placed in the first quadrant in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effects of Circuit Breakers on Average Prices of Stocks

Notes: This figure depicts the pairs of estimation coefficients (b1, b2) in Equation (4), for 100 constituent stocks from CSI 300. The dependent variables is the average price. The ±5% and ±7% are tested separately.

However, when we observe the pair of ±5% thresholds, in Figure 2, only four stocks fall into the first quadrant while 96 stocks fall into the third quadrant. When we observe the pair of ±7% thresholds, none of the stocks fall into the first quadrant. The negative b1 or b2 imply that the stock value will be decreased when the market fluctuates largely.

Following Chordia et al. (2002), we report the detailed statistics and average coefficients of Equation (4) in Table 4. The cross-sectional averages of (b1, b2) are (−0.32, −0.21) when we test the pair of ±5% thresholds, and (−0.11, −0.13) when test the pair of ±7% thresholds. These results indicate that circuit breakers are necessary to protect the stock price against the large market fluctuation, and thus do not support H3.

| Average Price | Price Change | Return | Turnover Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: 5% Circuit Breakers | ||||

| b1 | −0.32 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 2.53 |

| (−4.01) | (0.97) | (2.74) | (2.25) | |

| b2 | −0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.10 |

| (−52.39) | (−0.62) | (−0.09) | (−516.60) | |

| % positive | 4% | 11% | 0%. | 6% |

| % significant | 80% | 33% | 70% | 98% |

| Panel B: 7% Circuit Breakers | ||||

| b1 | −0.11 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 13.22 |

| (−4.98) | (−0.20) | (0.64) | (6.24) | |

| b2 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −1.64 |

| (−34.09) | (−2.18) | (0.55) | (−402.89) | |

| % positive | 0 | 2% | 2% | 12% |

| % significant | 97% | 40% | 78% | 93% |

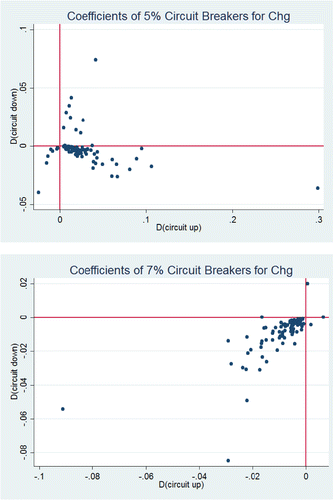

Next, we take price change (Chg) as DV, run Equation (4) and make the scatter plots of (b1, b2). The price change is the difference between the stock price Pt in minute t and the closing price of the previous trading day. It reflects the change of stock intrinsic value and a large price change implies an increase of stock value. Therefore, if the over-threshold market fluctuations benefit price change, (b1, b2) will be positive and then falls into the first quadrant. Figure 3 depicts that when we observe the pair of ±5% thresholds, only 11 stocks fall into the first quadrant; when we observe the pair of ±7% thresholds, only two stocks remain in the first quadrant, whereas 98 stocks are in the third quadrant. In other words, both upward and downward market fluctuations lead to a decrease of stock value, and this impact spreads up to 98% of the stocks. The results of Figure 3 are consistent to the results of Figure 2 and further confirm the necessity of circuit breakers in China financial markets. Similarly, results in Table 4 also show no evidence that over-threshold market fluctuations may increase value of individual stocks. Thus, the results do not support H3.

Figure 3. Effects of Circuit Breakers on Price Change

Notes: This figure depicts the pairs of estimation coefficients (b1, b2) in Equation (4), for 100 constituent stocks from CSI 300. The dependent variables is the price change (Chg). The ±5% and ±7% are tested separately.

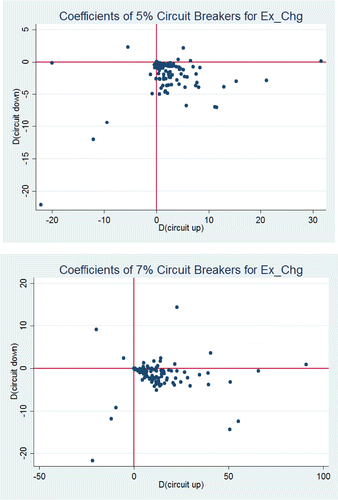

Third, we take stock return as DV, and investigate how the over-threshold market fluctuation affects the instant stock profitability. Defined as lnPtPt−1, the stock return at minute t is the instant change of stock prices from an intraday level and a high return means more gains. In Figure 4, when we observe the pair of ±5% thresholds, none of the stocks fall into the first quadrant; when we observe the pair of ±7% thresholds, only two stocks are in the first quadrant. The stocks are placed in the third and fourth quadrants in both plots. The results indicate that for almost all the stocks, their returns will decrease when the market moves downward. For some stocks, both upward and downward market fluctuations have negative impact on their returns. Coefficients in Table 4 also show that there is no benefit from large market fluctuations for the increase of individual stock returns. Therefore, circuit breakers are needed, especially on the downward side. The results do not support H3.

Figure 4. Effects of Circuit Breakers on Stock Return

Notes: This figure depicts the pairs of estimation coefficients (b1, b2) in Equation (4), for 100 constituent stocks from CSI 300. The dependent variables is the stock return. The ±5% and ±7% are tested separately.

Fourth, we evaluate the liquidity by the turnover rate of stocks (Ex_Chg). Figure 5 shows that only six stocks are located in the first quadrant when we observe the pair of ±5% thresholds of circuit breakers, and Table 4 confirms it. Similar to Figure 4, the majority of stocks are located in the third and fourth quadrants. As an implication, market fluctuations, especially downward fluctuations, will decrease the turnover rates for stocks and make the trading illiquid. These results do not support H3.

Figure 5. Effects of Circuit Breakers on Turnover Rate

Notes: This figure depicts the pairs of estimation coefficients (b1, b2) in Equation (4), for 100 constituent stocks from CSI 300. The dependent variables is the turnover rate (Ex_Chg). The ±5% and ±7% are tested separately.

In summary, we study different variables that relate to the liquidity and value of individual stocks, and examine how they behave when there is a market fluctuation beyond the thresholds of circuit breakers. Results indicate that when the market fluctuates at an extent beyond the thresholds of circuit breakers, the prices of individual stocks will decrease sharply. The over-threshold market fluctuations also have negative relationship to the price change and return of stocks, implying negative impact on the value and profitability of individual stocks. In addition, large fluctuations also lower the turnover rates of stocks and consequently lower the market liquidity. According to our empirical analyses with intraday data, the results above apply to over 95% of the stocks in Chinese markets. Therefore, our results find no evidence to show that the circuit breaker mechanism impedes the market liquidity and pricing discovery and H3 is not supported. On the contrary, the results confirm that the circuit breaker mechanism is really necessary to be implemented in order to provide protection to the market.

4. Conclusion

The circuit breaker mechanism has become an important instrument for financial market risk management and been widely employed in global financial markets. However, as an exception, it was suspended after a short-life implementation for only four days in China. This aim of this study is to explore whether the circuit breaker mechanism impedes the operation of Chinese financial markets. To answer this question, we specify our study by investigating three hypotheses: (1) the thresholds of circuit breakers (±5% and ±7%) are set too low and easy to be triggered; (2) the thresholds of circuit breakers are too close to each other, and therefore generate the “magnet effect” to accelerate the market to reach threshold Level II after passing Level I; (3) this circuit breaker mechanism impedes the market liquidity and pricing discovery.

Using a minute-stamped intraday dataset including performance of both the overall market and individual stocks, we first find that in the historical records, very few cases are qualified to trigger circuit breakers, and the cumulative time length of these qualified cases only count 2% of the full time length of observations. Second, our results show that when market fluctuates over the first threshold level of circuit breakers, there is no certainty to aggravate forward to the second threshold level. Therefore, the magnet effect does not exist. Third, we investigate individual stocks and find that without circuit breakers, large market fluctuations have negative impacts on individual stocks from diverse aspects. In conclusion, our study does not support the three hypotheses with negative comments on circuit breakers. On the contrary, Chinese financial markets still need a circuit breaker mechanism to protect investors’ benefits and maintain the market liquidity and stability.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71803012), the Beijing Talents Fund of China (Grant No. 2016000020124G051), and Beijing Normal University and UniSA Business School Seed Funding.

The author thanks Euston Quah (Editor), Jackson Teh, Yulin Jiang and two anonymous referees. The author also thanks Zhenyu Cui, Ionut Florescu, Shi Li, Blu Putnam, Honglei Zhao, participants at the 7th BNUBS-GATE Workshop, Illinois Economic Association 46th Annual Meetings, and the 7th Annual High Frequency Finance and Data Analysis, for helpful comments and feedback.