Application of digital micromirror devices (DMD) in biomedical instruments

Abstract

There is an ongoing technological revolution in the field of biomedical instruments. Consequently, high performance healthcare devices have led to remarkable economic developments in the medical hardware industry. Until now, nearly all optical bio-imaging systems are based on the 2-dimensional imaging chip architecture. In fact, recent developments in digital micromirror devices (DMDs) are gradually making their way from conventional optical projection displays into biomedical instruments. As an ultrahigh-speed spatial light modulator, the DMD may offer a range of new applications including real-time biomedical sensing or imaging, as well as orientation tracking and targeted screening. Given its short history, the use of DMD in biomedical and healthcare instruments has emerged only within the past decade. In this paper, we first provide an overview by summarizing all reported cases found in the literature. We then critically analyze the general pros and cons of using DMD, specifically in terms of response speed, stability, accuracy, repeatability, robustness, and degree of automation, in relation to the performance outcome of the designated instrument. Particularly, we shall focus our discussion on the use of Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS)-based devices in a set of representative instruments including the surface plasmon resonance biosensor, optical microscopes, Raman spectrometers, ophthalmoscopes, and the micro stereolithographic system. Finally, the prospects of using the DMD approach in biomedical or healthcare systems and possible next generation DMD-based biomedical devices are presented.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement in semiconductor processing technology in the recent years has brought significant improvement in performance capability reduction in production costs and device size, which in turn has resulted in rapid expansion of Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS) in many electronic sensing and actuation systems. The ability of MEMS to execute programmable mechanical movements with high pixel counts and at high speed on a single chip has opened up many new application opportunities that were previously impossible.1,2,3 This paper aims to provide an informative up-to-date summary on the rapidly growing sector of using digital micromirror devices (DMDs) in biological and healthcare instruments in the last decade. In light of their technological significance, we have focused particularly on representative applications including real-time surface plasma resonance biosensors, biological microscopes, the ophthalmoscope, and micro stereo-lithographic systems. The advantages and disadvantages of introducing DMDs in these applications, as well as solutions to overcome traditional limitations, are discussed. As closing remarks, future prospects of novel DMD-based systems and their implementation are analyzed to identify possible motivations for the next generation of MEMS-based healthcare instruments.

2. Digital Micromirror Device

2.1. Basic concept

As depicted in Fig. 1, the surface of the semiconductor chip contains a 2-dimensional array of aluminum mirrors, in which individual mirrors can be deflected by a torsion hinge yoke across the bottom of each mirror. A CMOS static random-access memory (SRAM) cell underneath each mirror is used for latching the digital mirror position identifier data. When the SRAM activates one of the electrodes, the corresponding mirror angle is pulled down by the electrostatic force to form 12∘ deflection in a limited space. Consequently, a voltage pulse applied to the micro-mirror actuation SRAM will rapidly flip the mirror to its opposite state, i.e., toggling between +12∘+12∘ and −12∘−12∘.4,5

Fig. 1. DMD microstructure. (a) Layer structure model of each unit in DMD. (b) Triggered DMD unit tilts into a pair of deflection in two angles.

An overview of DMDs and Digital Light Processors (DLP) standard can be found in Chipset Selection Guide. The DMD is an array of micromirrors primarily used for high speed, efficient, and reliable spatial light modulation.6 High density microscopic rectangular mirror pixels, with a total count up to 4.1 million, are available for programmable on-off switching down to pixel level. To toggle between the on and off states, the mirrors have an angular deflection of ±12∘±12∘ along the diagonal axis for DMD pitch of 13.6, 10.8, and 7.6μμm, and ±17∘±17∘ for the case of 5.4μμm pitch. Grayscale at 10-bit resolution is achieved through varying the reflectivity duty cycle using pulse width modulation (PWM). DMDs are widely used as the optical processing engine for projection displays.7

2.2. DMD optical efficiency for visible spectrum

Under fully optimized conditions, the calculated overall reflection efficiency or the entire visible spectrum (400–700nm), after having taken into account the optical power loss due to mirror diffraction, intrinsic absorption at mirror surface (typically aluminum has a reflectivity of 89%) and design induced reduction in fill factor, for various typical pixel dimensions are listed in Table 1.8 It is worth pointing out that the present calculation does not include system-level efficiency losses such as etendue mismatches. In high-end DMD modules, the optical window possesses an anti-reflective coating to maximize transmission efficiency.

| DMD pitch | Tilt angle (deg) | ff/number | Diff. eff. (%) | On-state fill (%) | Window transmission (double pass) (%) | Mirror REFL (%) | Total EFF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13.6 | 12 | 2.4 | 89 | 92 | 96 | 89 | 70 |

| 10.8 | 12 | 2.4 | 87 | 92 | 96 | 89 | 68 |

| 7.6 | 12 | 1.7 | 82 | 94 | 96 | 89 | 66 |

| 7.6 | 12 | 2.4 | 84 | 94 | 96 | 89 | 67 |

| 5.4 | 17 | 1.7 | 86 | 93 | 96 | 89 | 68 |

| 5.4 | 17 | 2.4 | 80 | 93 | 96 | 89 | 64 |

2.3. DMD control electronics

Several developer modules have been produced by Texas Instruments and third-party companions to ensure sufficient levels of programming simplicity and man–machine interactive capabilities. The DLP Discovery 4100 Development Platform, which consists of six evaluation modules, is a convenient package to achieve DLP programming through the USB port known from DLP® DiscoveryTM 4100 Development Platform. The DLPLCRC410EVM controller board provides developer’s scalability to port their DLP design work across multiple DMDs. A small set of scrolling test patterns are stored in the controller, which allow customers to test their optical configurations. Programmed pattern data can be sent via USB to the on-board application field-programmable gate array (FPGA) for subsequent display on the DMD. Users of the D4100 can work with visible, UV, and NIR light with pixel-level precision and fast pattern transfer rates, such as DLP650LNIR Maximum Binary Pattern 12500 Per Second in wavelength: 800–2000nm, DLP7000 Maximum Binary Pattern 32552 Per Second in wavelength: 400–700nm and DLP7000UV Maximum Binary Pattern 32552 Per Second in wavelength: 362–420nm.

Software supplied by the manufacturer can control the main functions of the Discovery series control boards and sub-boards. Access to advanced functionality and application development can be performed by a graphical programming language (such as LabVIEW by National Instruments) or a programming language (such as C/C ++).

The power handling capacity of DMD modules is primarily governed by the areal size of each pixel. Typical DMDs can withstand optical intensity levels ranging from 50 to 2000 lumens, which correspond to the total DMD chip diagonal length of 0.20–0.66 inch.9 Understandably, larger DMD size also comes with higher cost.

2.4. Spatial light modulators (SLMs): DMD versus LC-SLM

Spatial light modulators (SLMs), which allow pixel-wise transmission switching, are very useful for precise and dynamic shaping of light beams through a computer interface, thus bringing many possibilities for the design of next-generation advanced optical systems.10,11,12,13 While most of the pioneering experiments reported in the literature have been based on liquid crystal (LC)-SLMs, their limited switching frequency means that it usually requires several minutes to obtain a single frame containing several thousand pixels of data at a refresh rate of 10–200Hz.14 DMD-based on MEMS technology has become an effective solution due to their fast binary pattern refresh rates up to 32kHz and high-speed data rates up to 48Gbps, as offered by DLP Discovery 4100.

The researchers report a parametric assessment of the performance of LC-SLMs and DMDs as diffractive elements in the ballistic, highly scattering and intermediate regimes in detail.15 A modular experiment was designed to study the performance characteristics of LC-based SLMs and DMDs in the three main regimes, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Modular experimental setup.15 1. Ballistic regime. 2. Diffusive regime. 3. MMF with internal (a) or external (b) phase reference.

In the case of the LC-SLM, the modulator’s slow refresh-rate has restricted the scope for the system to sequentially optimize the phase of all subdomains. On the other hand, replacing the LC-SLM with a DMD may resolve the problem after increasing the frame rate up to 10 times. The DMD modulation rate is higher than that of the nematic LC by several orders of magnitude. In the off-axis regime, DMDs are superior in modulation as well as in beam-shaping fidelity, as compared to LC-SLMs. The power ratio of an LC-SLM-based system is 60% at the target focal point, while its DMD counterpart operating in an identical regime has a ratio of 75%, which may bring benefits to imaging systems for high contrast. Furthermore, DMDs are free of phase flickers, which are common in LC-SLMs and may degrade the precision of phase measurements. The work also revealed that the diffraction efficiency in the case of DMD is only 8%, which is significantly lower than the 42% found in LC-SLM, although this can be compensated by increasing the power of the laser source.

There is a fundamental difference between the control outcome of DMD and LC-SLM. The latter controls the signal by the continuous analog signal. The refresh rate of general LC-SIM is 10–200Hz. It regularly takes several minutes to acquire a single frame containing several thousand pixels of data. In further research, the LC-SLM combined with faster beam steering technology increases the acquisition rate.16 DMDs based on micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) technology as a pure binary amplitude modulator, can be controlled more precisely with the precision and efficiency of each degree of freedom. Using DMD instead of LC-SLM reduces the calibration time by more than 10 times (limited by the camera refresh rate), DMD can operate accurately at 22kHz, and the maximum update rate for DMD can be up to 32kHz with the improvement of MEMS technology. MEMS-based devices outperform the LC analogues not only in speed but also in the fidelity of the obtained foci. Therefore, in terms of accuracy and refresh effectiveness, optical imaging system based on DMD as a space light modulator offers potential advantages in a wide range of applications.

3. Modern Health Instruments Based on DMD

3.1. Application of DMD in biological microscopy

In this section, we review the application of DMD in biological microscopy and evaluate the relative merits as compared to the conventional methods. Based on solid theoretical foundation of optics, the topic of microscopy has grown into a highly demanding scientific discipline that undergoes continuous improvement. Modern optical microscopes routinely offer three-dimensional (3D) image reconstruction for bio-imaging,17,18,19,20 examples of such techniques are tomographic phase microscopy based on quantitating phase imaging (TPD),21,31,48 X-ray computed tomography (CT) based on the back filtered projection method, optical diffraction tomography (ODT)22,32 and confocal microscopy.31

Recent progress in MEMS technologies has enabled DMDs to become a key component in imaging systems. MEMS with feature sizes between 1 and 100 micrometers are widely used in precision instruments with a high level of integration. The hardware design, in terms of response speed, stability, accuracy, repeatability, robustness, and degree of automation, have also made significant contribution towards the capability and performance of the system. Over the past 10 years, we have seen significantly increased efforts to apply hardware advancements to solve the practical life science and healthcare problems.

3.1.1. Optical diffraction tomography

Optical diffraction tomography provides label-free imaging reconstruction of biological samples without the use of exogenous labeling agents or dyes, such as fluorescence protein, organic/inorganic dyes, and quantum dots, thus offering the possibility to optimize complicated bio-sample detection processes and side-effects e.g., photo-bleaching or photo-toxicity, introduced by labeling agents or dyes.

Wolf, who has been leading the pace of theoretical development of ODT, published a series of papers in 1969 to investigate the inverse scattering problem, thus making it possible to measure the refractive index (RI) distribution in semi-transparent objects as well as the amplitude, phase of scattered fields by geometrical interpretation.23 From the late 70s, more experiments and computational simulations were conducted by Fercher et al. to study the 3D scattering potential of microscope objects.24,25 After 2010, due to improvements of laser source and digital signal processing, ODT has become an invaluable method in optical microscopy for 3D reconstruction of bio-samples.26,27 Moreover, the excellent reviews by Bailleul and Haeberle et al. on ODT have provided a thorough comparison with conventional wide field microscopy.28

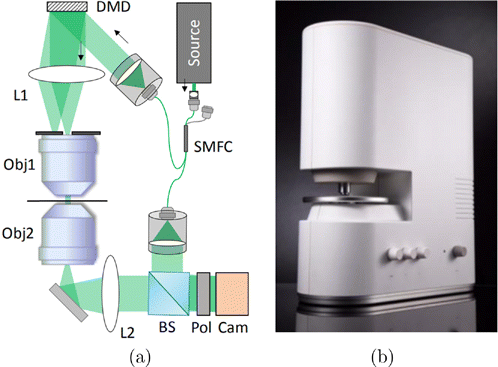

The high degree of flexibility in terms of pattern format and speed of feature movement afforded by DMD has greatly facilitated the development of optical diffraction microscopy.29,30 Millions of individually switchable micromirror are lined up on DMD surface, which exploits the control of illumination beams at the speed of over tens of kHz. DMD is used in optical diffraction tomography to obtain a stable analysis of 4D refractive index tomography of cells with the principle of Lee hologram.31 The optical system presented in Fig. 3(a) is integrated into a stand instrument, as shown in Fig. 3(b).32

Fig. 3. (a) Optical setup for optical diffraction tomography based on DMD.32 (b) Commercialized version of the 3D holographic microscope.

It is critically important that ODT must require highly stable and precise control of the incident angle in the optical system. For this reason, DMD fits the situation very well by providing completely solid-state angular modulation with very stable mechanical stability and very high speed, not to mention the possibility of programmable random access at pixel level. Lee reported a time-multiplexed structure illumination scheme, which enables an illumination wavefront to be generated with precisely defined spatial frequencies and at the same time eliminates unwanted diffracted beams that may deteriorate the image quality in Fig. 4.33 They measured the 3D Refractive Index distribution of live biological cells to show the instrumental capability of the method. The reconstructed tomograms in Fig. 5 showed a high RI sensitivity of σΔn the standard deviation of 3.15×10−4.

Fig. 4. Experimental setup.33 (a) Optical setup based on Mach–Zehnder interferometry. The structured illumination displayed onto a DMD is projected onto a sample plane. (b) The schematic of 51 spatial frequency components addressed. The gray arrow indicates the direction of circular scanning.

Fig. 5. Cross-sectional slices (left panel) and 3D rendered images of the reconstructed 3D RI distribution of (a) a red blood cell and (b) a HeLa cell.

3.1.2. Structured illumination microscopy

In 2017, Wang et al.34 combined DMD, which was effectively used an spatial light modulator, with electrically tunable lens (ETL) to form a new high-speed 3D structure illumination imaging system in Fig. 6. In the recent years, structure illumination microscopes (SIM) are increasingly being adopted as a solution for high speed 3D bio-sample assessment in light of their merits in speed, measurement precision, practicability and system simplicity. Compared with the liquid-crystal-based spatial light modulator, which offers a limited speed of hundreds of Hz, DMD are capable of producing structured images at speed of 4.2 to 32.5kHz with a wider spectral range.35,36,37 Meanwhile, the conventional galvo-scanner and scanning gratings schemes may have similar speed, but there is limited scope for varying the projected fringe pattern.38

Fig. 6. Optical configuration of the DMD-based SIM system.34 L1, L2, and L3 denotes collimating lenses; M denotes high-reflectivity mirror and DM denotes dichroic mirror.

In 2013, Dan39 and co-workers introduced a novel design for achieving SIM using DMD, as shown in Fig. 7, for fringe projection. While a simple low-coherence LED light was used as the illumination source, the experimental setup showed a lateral resolution of 90nm and the optical sectioning depth of 120μm, and 930nm sectioning strength with maximum acquisition speed of 1.63×107pixels/s. The low-cost, high-speed SIM system was only limited by the speed of the imaging camera, which operated at 7000Hz. A high-speed camera e.g., FASTCAM SA-Zcamera (Photron) may further expand the speed to 21,000 fps.37,38

Fig. 7. Scheme of the DMD-based LED-illumination SIM microscope.39 A low-coherence LED light is introduced to the DMD via a TIR-Prism. Inset (a) shows the principle of the TIR-Prism. Inset (b) gives the configuration of the system, including the LED light guide (①), the DMD unit (②), the sample stage (③), and the CCD camera (④).

Qian et al. reported a DMD-based color SIM and used the setup to study the world’s largest biological group — Coleoptera40 use actual number when inserted to text. It was shown that the system has favorable performance in the six elements of microscope imaging, namely, high resolution, large field-of-view, 3D, rapid imaging, natural color, and quantitative analysis, as compared to the conventional confocal laser scanning microscopes (CLSMs). Uniform lighting was achieved by optimizing the coupling method between DMD and LED, which led to an increase of four times in the energy efficiency of LED output and objective access. The exposure time of a single snapshot has been reduced from several hundred milliseconds to several milliseconds. The increased imaging speed contributes a solid foundation for large-scale image acquisition. Combined with the realization of a new data processing algorithm based on HSV color space, the reported full-color SIM has the potential to play an essential role in the study of material surface morphology.41

Zheng et al.42 developed a light scattering microscope, which merges light scattering spectrum with microscopic imaging, for detecting the size of confined particles. The instrument offers the possibility of using DMD to vary the diameter of the iris, which in turn is used as a Fourier spatial filter. A practical setup, including microscope configuration and generation of DMD filters, has been implemented to eliminate position-related problems in the conjugate Fourier plane, thus enabling the characterization of particle shape and motion direction. The system is capable of producing a LaGuerre–Gaussian optical tweezer for studying the transfer of bundled particles by varying the orbital angular momentum of a laser mode.43

3.1.3. Quantitative phase microscopy

Multiple quantitative phase imaging (QPI) schemes capable of performing 2D and 3D sample analysis were first reported in the 1990s.44,45 The phase data, if obtained from a scattered distribution, may provide useful information on the internal structure of the specimen, particularly those of biological nature.46,47

In the last 10 years, a number of new QPI schemes have been reported.48,49,50,51,52 Subsequently, QPI has become a pioneering label-free imaging system for the analysis of bio-specimens. Full-field QPI registers the interferogram generated between the reference and imaging fields, hence providing a channel to obtain phase distribution introduced by the presence of the sample. Here, we present two representative DMD-based common-path QPI systems.

The scheme53 has adopted an active DMD to manage the illumination beam, which varies the interference edge periodicity projected on the camera to meet sampling conditions and also simplifies the alignment process of the pinhole. A schematic of their DMD-base common-path QPM is shown in Fig. 8. The individually switchable micro-mirrors generate two beams, one for imaging and the other for reference, at a particular angle for achieving the required interference effect. A liquid crystal device is also placed at the objective back aperture plane to decrease specular reflection noise. The incorporation of a LCD device can completely remove all DMD-related residual signals, which significantly improves edge contrast. It is worth mentioning that experimental phase images still contain noise caused by interference between multiple reflections as their system used a highly coherent laser source.54

Fig. 8. Schematic of the DMD-based common-path QPI system.53 The inset shows a magnified view of a DMD region with “off” or “on.”

Shin et al.29 presented a design that uses DMD for controlling the illumination beam of the QPI system. By using appropriate spatial filtering to display binary illumination pattern on DMD, the illumination angle of the beam on the sample can be controlled systematically with high speed and high stability, and plane waves with various illumination angles can be generated and incident on the sample. Then the complex optical fields of the samples obtained at various incident angles were measured by the Mach–Zehnder interferometry, from which high-resolution 2D synthetic aperture phase images and 3D refractive index fault maps of the samples (including individual colloidal spheres) and biological samples (including human RBC and HeLa cells) were reconstructed.

3.1.4. Digital holography

Digital holography provides a means of extracting optical phase distribution in the signal beam that has traversed through the sample or reflected off its surface. González55 reported a single-pixel digital holography system. The illumination part consists of a DMD working as a SLM. A specific phase-encoded Hadamard pattern was projected on the object through the use of a DMD. The same device also enabled wavefront correction in the illumination light. The phase errors produced by the lens or mechanical movements can be compensated further by managing the binary patterns that are used in the phase extraction process. The reported single-pixel digital holography system also has the merit of cost-effectiveness. Their experiments revealed that the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was 12dB for conventional digital holography and 9dB for single-pixel digital holography.

In addition, DMDs can also be used as wavefront modulators. The optical phase can be precisely controlled by a DMD through an off-axis holography technique based on using a large number of pixels working at a fast speed up to a few kHz. Fast wavefront shaping employing a DMD, was also demonstrated through the use of diffusively moving scatters.56 High-speed wavefront shaping is crucial for in vivo biomedical applications. However, the diffraction efficiency of DMDs is low due to the grating nature of the subpixels. The characteristics of representative types of wavefront modulators, i.e., SLM, DMD, and deformable mirror (DM) are summarized in Table 257 as well as the representative types of wavefront modulators and their characteristics in Table 3.

| Reduced scattering coefficient μ′s (cm−1) | Anisotropy g | Absorption coefficient μa (cm−1) | Wavelength λ (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast tissue | 9.189 | 0.957 | 0.9 | 1000 |

| Liver tissue | 8.112 | 0.952 | 0.5 | 1064 |

| Aorta | 23.9 | 0.90 | 0.5 | 1064 |

| Myocardium | 6.408 | 0.964 | 0.3 | 1064 |

| Enamel | 2.4 | 0.96 | <1 | 632 |

| Cranial bone | 19.48 | e | 0.11 | 800 |

| ZnO layers | ∼2000 | e | ∼0 | 633 |

| Spatial light modulator (SLM) | Digital micro-mirror device (DMD) | Deformable mirror (DM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working principle | Electrically controlled liquid crystals arrays | Tilting of micro-mirror arrays | Piezoelectric arrays and flexible reffective surface |

| Pixel number | High (∼800 600) | Ultra-high (∼3000 2000) | Low (∼200 5000) |

| Control speed | Slow (10,100 Hz) | Ultra-fast (>kHz) | Ultra-fast (>kHz) |

| Cost (in USD) | ∼30 K | ∼20 K | ∼50–100 K |

| Diffraction efficiency | ∼30–90% | <50% | ∼100% |

| Major manufacturers | Hamamatsu, Holoeye | Texas Instruments | Boston micromachines |

3.1.5. Micro-tomography

DMD’s versatility for generating programmable reflector patterns at high switching speed has also enabled micro-tomography. Similar to light-field microscopy, the 2D image of the sample can be generated from a certain perspective angle on account of the illuminated pattern encoded by the DMD. In this condition, they achieve tomographic imaging by digitally refocusing the object at different depths without the need of mechanical offset made by physical scanning. A point worth noting is that the spatial information comes from the encoded lighting, and the angle information is related to the different positions of the single-pixel detector. The proposed method provides a link between single-pixel imaging and micro tomography. The trade-off between spatial resolution and angular resolution is eliminated. Experimental results indicate that the resolution of the Fourier basis patterns (also called sinusoidal intensity patterns) loaded on the DMD dominates the performance retrieved from the single-pixel detector, which means that the angular information can be recorded in the detection side without sacrificing the spatial resolution.58

3.2. Application of DMD in spectrometers

In a conventional optical spectrometer, light emerging from an optical fiber or free-space relay optics will first go through a slit aperture. The beam is then collimated by a collimating mirror before hitting a diffraction grating, which angularly disperses the input beam according to wavelength. Grating characteristics, including groove density and dispersion, are important considerations when building a spectrometer. The diffracted beam, which may be further focused using a second reflective mirror, is analyzed by a linear detector array. Each pixel describes a division of the spectrum that is translated into a response using a spectrometer software.

Miniature spectrometers are widely available nowadays because of the constant need to analyze wavelength-dependent parameters in almost all branches of Science and Engineering. Several MEMS-based spectrometers are already commercially produced to meet market demand. Here, we specifically highlight the development of DMD-based spectrometers.

Several review papers on the use of spatial light modulators within the broad field of Raman spectroscopy have been published. Research on new spectroscopy systems taking advantage of DMD’s capabilities is emerging fast in academia in recent years.59 Wagner et al. first reported a cost-efficient solution to produce a DMD-based optical spectrometer that only uses a sensitivity optimized photomultiplier tube (PMT).60 In their design, the DMD was adopted as a selector located at the image point of a spectrum created by a concave grating to manage the specific wavelength components of the incident light. Switching of individual micromirror effectively resulted in sweeping the monochromators for different angles. Compared to the conventional dispersive spectrometer, which operates by rotating the grating to change the wavelength, a pre-dispersive spectrometer based on DMDs eliminates the mechanical error and radically increases the analysis and detection speed and improves the detection limits.

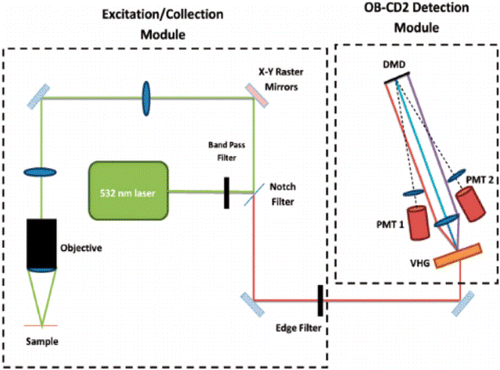

Owen G presented an optimized binary compressive detection strategy in which all of the collected Raman photons are detected using a pair of complementary binary optical filters that direct photons of different colors to two photon counting detectors.61 This new strategy (OBCD2) uses two detectors to count all of the collected photons transmitted by two complementary binary optical in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. Schematic of the OB-CD2 Raman system with a 532 nm excitation laser.61

The two PMTs in the system are for collecting all the backscattered Raman photons using a single objective lens placed immediately after a volume holographic grating. Photons of different wavelengths will hit different pixels on the DMD. Consequently, the DMD may act as a scanning device to select wavelengths for detection by the two PMTs. A total of 342 different wavelength ‘bins’ corresponding to a Raman wavenumber range of ∼12cm−1.

With an optimized algorithm, combined with the OB-CD2 strategy, the scheme was shown to be capable of precisely measuring Raman scattering rates at speeds up to 3ms per measurement and a compilation of Raman images in a second.

Kevin and Zoran conducted a comprehensive investigation on the use of DMD for precision SIM imaging and spectroscopy. They prudently analyzed the limits of scattering characteristics, diffraction efficiency, and MTF performance of DMD devices for precision imaging instruments.62 They concluded that one has to consider a set of design rules in order to maximize the potential of DMDs for the applications considered.

In another review paper,63 the performance between LC-SLM and DMD in microscopy for various applications has been analyzed. The authors reported that LC-SIM has not been a popular device for processing Raman scattered photons because of the losses incurred to the weak Raman signal, despite that high-quality LC-SIM may have sufficient throughput for such applications.64 On the other hand, DMD offers a range of merits including efficient photon throughput, close to zero wavelength dependence [total throughput can be >90% for visible-NIR (Vis-NIR) light] and larger fill factor, which will make DMD a device of choice for spectroscopic applications.

Cebeci65 reviewed the latest progress in compressive Raman detection based on the optimized binary compressive detection (OBCD) strategy with DMD and compared the technique with CCD-based Raman Detection. Scott et al. experimentally showed that the performance of a custom DMD-based system against two commercial spectrometers based on CCD and EMCCD for detecting low concentrations of bio-related components.66,67,68 Compared with state-of-the-art commercially available hyperspectral Raman systems, DMD-based compressive Raman technology (CRT) using a new Cramer–Rao lower bound (CRB)-based algorithm is ×100 times faster than the CCD-based system and ten times faster than the EMCCD-based system in the high signal regime where all systems can perform successful species quantitation.

As a spatial light modulator, DMDs are used for transforming the light fields into some field patterns to improve the detection performance such as speed or spatial resolution. Duncan explored using DMD as an adaptive reflective slit for very low light flux Raman Spectroscopy.69,70,71 In the micro-mirror-based adaptive slit spectrometer configuration, the Raman spectral region is “modulated” or turned on and off. They are able to see significant variations in the photonic signatures in the Raman band that result in switching mirrors “all on” versus “all off.” Observing a 40–50% mirror array modulation of the signal from an “acetaminophen” sample reference could achieve expected S/N for a strong Raman signal (10−6) and the other representing a weak Raman signal (10−8).

3.3. Application of DMD in ophthalmoscope

Ophthalmoscopy is a test that allows in-depth evaluation of the pupil of the eye through the fundus, as well as cornea, lens, vitreous fluid, and aqueous humor. It is employed to evaluate symptoms of various retinal vascular diseases or eye diseases such as glaucoma and retinal detachment.

Piotr B72,73 used DMD to achieve optimal illumination for diabetic retinopathy detection. Specifically, the team designed an illuminate pattern, which was realized with DMD, to be projected on the retina. This approach was showed to improve the visibility and contrast of retinal lesions. Results from in vivo experiments in group samples showed that the new system offers a contrast improvement of 30–70% based on images taken under spectrally optimal illuminations using DMD. Optimized illumination therefore has high potential for the next generation of retinal imaging systems offering rapid screening speed, improved feature extraction, and user-programmable imaging characteristics.

Structural and functional changes in the ocular fundus can provide important information related to retinal pathologies. While a number of new approaches to monitor the retinal imaging have received much attention, image contrast is still a challenging parameter of imaging quality because of reflectivity fluctuations and scattering of out-of-focus light. Currently, a leading ocular fundus photography technique is based on scanning light ophthalmoscopy (SLO). Once again, DMD has been adopted in retinal imaging as a spatial light modulator. Spatial flexibility and programmability of DMD has improved the system in terms of speed and imaging precision. A single line scanning module is based on DMD incorporated in a nonmydriatic confocal retinal imaging system by Muller et al.74

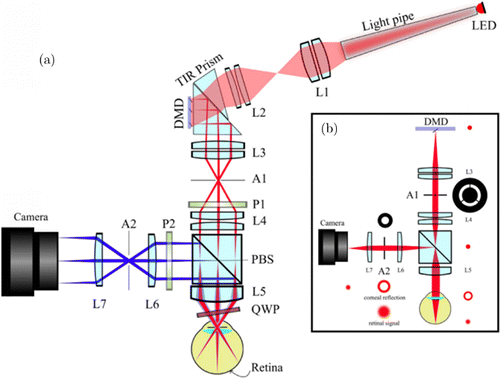

In another publication by Vienola et al.,75 the team developed a ophthalmoscope based on DMD to compensate for eye movement.76 The optical system used an LED with a bandwidth of 30nm and a center wavelength of 810nm as a light source and a DMD with a 0.7inch diagonal micromirror array as the spatial light modulator, as shown in Fig 10. DMD was used for generating concentric circles in the illumination pattern. By shifting the center of the concentric pattern, it was possible to change the area of interest within the retina. They used an annulus to create a circular illumination on the cornea and a circular aperture to block most corneal reflections that might interfere the signal. Figure 11 shows the in vivo results of different regions of the retina by projecting concentric circles with centers at two different locations in the DMD. Annular illumination and detection can suppress reflections in the central portion of the cornea to reduce imperfect optical noise and improve the signal-to-noise ratio. To overcome the drawback of the illumination light efficiency using a DMD, one has to increase the fill factor, which is still a challenging task.77,78

Fig. 10. (a) Schematic of the optical setup showing both the illumination path (red) and the reflection path (blue). (b) The optical paths and beam shapes at different positions in the setup to block the corneal reflection.75

Fig. 11. (a) Fundus photograph of subject 2 showing the macular region (blue dashed circle) and the ONH region (red dashed circle) oh the ocular fundus. (b) The macular region with fovea indicated by the red arrow. (c) The OHN (indicated by red arrow) with blood vessels surrounding it. Scale bar is 5∘ in the retina.75

In 2018, Kari et al.79 studied in vivo motion tracing in different Scanning laser ophthalmoscopy SLO76,78 for high-speed fixational eye detection adopting DMD80 at 130Hz, reaching a motion detection bandwidth of 65Hz.

The structured illumination allows the acquisition of subsampled snapshots of the retina, which are then compared to a full confocal frame (a reference frame) to estimate the eye motion using cross-correlation analysis. DMD-based SLO system helps the averaging of images for improved SNR as the images can be registered together with higher accuracy based on the motion information. The motion detection accuracy was better than 0.77 arcmin in vivo corresponding to 3.7μm on the retina. A total of 1000 sub-sample frames were taken in the experiment. DMD fill factor of 0.05 will create 50 full confocal images within eye rotation in 7.6s. Image after calibration has a transparent texture of blood vessels with reasonable degree of expansion and high contrast.

Martins and Vohnsen reported a continuous aperture scan of the pupil using a DMD in order to conduct astigmatism measurement without the need of a lenslet array. The high-operation speed and sequential scanning capability of DMD greatly improved the measurement dynamic range. Meanwhile, they showed that wavefront sensing based on DMD also corrected visual aberrations of the eye by offering sequential field scanning of the wavefront. The procedure of this program is explained in detail. They conducted extensive experiments to assess the characteristics of their system. First, they evaluated the wavefront reconstruction performance when different DMD fill factors were used. Using an artificial eye or real eye and multivariable control, the contrast levels under different wave aberrations was studied. They also tested the elimination of corneal reflexes or undesired corneal regions by deactivating corresponding pixels in the DMD. The experiments showed that Scans performed at 13 FPS could satisfy the needs of measuring ocular aberrations with both 5×5 and 10×10 micromirror sampling.75,81

3.4. Application of DMD in SPR

The phenomenon of anomalous diffraction as a result of the surface plasmon waves excitation was first discovered in 1902 by Wood.82 Surface plasmon polariton (SPP) is physical quantity to describe the resonant coupling of photons from polarized light to oscillation of free electrons in metal, resulting in a strong electromagnetic evanescent wave adhered to the metal surface and a charge oscillation-surface plasmon wave. In 1982, Lindeberg and Nylander83 demonstrated the use of SPR for optical biosensing with many benefits: (1) high sensitivity, (2) label-free detection, (3) real-time monitoring, (4) low volume sample consumption. The quantitative binding ability of the interaction between the molecules immobilized on the sensing surface and the probe molecules in the sample solution makes the SPR biosensor an essential method of identifying and quantifying biomolecular interactions.84,85

In 20th century, Phase interrogation SPR sensing was proposed in 1996 by Nelson et al. Two years later, Nikitin et al.86 reported the first phase SPR imaging (SPRi) sensor based on a Mach–Zehnder interferometer. In 2005, Wolf et al.87 developed a 2D angle-resolved SPRi system. In 2006, Fu et al.88 published a 1D SPRi system based on wavelength interrogation. Because of these pioneering endeavors, SPR research has become an indispensable technique in modern life science research.

Wang and Loo89 developed a high-speed, solid-state and programmable angle-resolved SPR sensor, and later further implemented a high-throughput 2D SPR sensor array, based on DMDs and single-point detector. In their design, a photodetector optimized for wide dynamic range and fast response was used instead of an imaging sensor. Consequently, the total hardware cost was reduced substantially. Apart from fast scanning speed, a unique and important feature of the design is the possibility to select any arbitrary interrogation point for rapid access of information according to users’ demand. DMDs were used for high-speed solid-state programmable angular scanning and spatial multiplexing to facilitate single-point detector-based signal detection. A schematic of their set up is shown in Fig 12. The light source is a helium-neon laser. After expansion by a telescope system, the beam is projected on a DMD. DMD device has a scanning speed of 4.2kHz. Each column of micromirrors on the DMD is divided into multiple section in the horizontal direction and they are selectively switched to “on” /“off” position to achieve scanning of the SPR excitation angle. This means that at any time, the detector only receives reflected light at a specific angle. All sensing elements can be addressed sequentially at high speed. In their experiments, the exposure time for a single point was set at 10ms. Therefore, for 45 angular steps, an angular scan was completed in 450ms. The total measurement time for the four channels is 1.8s.

Fig. 12. Optical configuration of the DMD-enabled SPR system based on angular interrogation of the Kretchmann scheme.89

The team later reported a 2D angular address-based SPR sensor array based on a single-point detection in Fig. 13. Two DMDs were used in the optical system, with one for angle interrogation and vertical spatial scanning and the other for horizontal spatial scanning.90 In the experimental set up, the calculated horizontal scanning resolution due to DMD1 was 0.07mm and the vertical scanning resolution due to DMD2 was 0.022mm. For each open window (an array of 5×5 sensors with 1.2×1.2mm2 for each sensor), selection of a proper incident angle for SPR excitation was performed by selectively switching columns of micromirrors in DMD2 to conduct 2D angular scanning. The team’s high-throughput aptamer screening experiments have demonstrated that the reported 2D addressing SPR scheme has high potential for downstream therapeutic applications.

Fig. 13. Schematic of solid-state angular interrogated 2D SPR sensor array for multiple aptamer screening.90

Spatial light modulators mainly control amplitude or phase modulation of optical wavefronts. As previously mentioned, DMDs offer higher switching speed as compared to conventional devices. Smolyaninov et al.91 demonstrated 2D control of free space optical fields at 1GHz modulation speed using DMD operating together with near-field interactions using an electrooptic SPR effect. The innovative feature of the work lies in the use a high χ(2) dielectric thin film as the active layer in a programmable plasmonic phase modulator (PPPM) array, which radically reduces the response time of the electronics addressing the transducer.

Utilizing this approach, the team achieved phase-dominant 4×4 spatial light modulation with individual unit modulation at the speed of 1GHz. Figure 14 shows the operating model of PPPM. The reported PPPM approach has two key advantages: solid-state operation with much reduced mechanical errors, and high thermostability. The switching speed is over three orders of magnitude higher than the state-of-the-art design based on MEMS, liquid crystal, and thermooptic modulation. Ongoing research on programmable space-variant light modulation at gigahertz rates has opened a path for ultrahigh-speed SIM.

Fig. 14. PPPM overview.91 (a) Illustration of PPPM operation. (b) Expanded view of the PPPM: (1) Si prism; (2) noble metal thin film for SPR (48nm Ag); (3) electrooptic dielectric modulation layer of SRN or AlN; (4) 4 × 4 electrode matrix and (5) sapphire wafer.

3.5. Application of DMD in micro stereo-lithography for cell microenvironment

Hydrogel is a hydrophilic three-dimensional network structure that can rapidly expand in water and maintains a large volume of water in the swelling state without dissolving. Because of its specific physical properties, hydrogels are used as a biological regeneration material matrix to mimic many of the healthy and diseased states of native tissues. The work by Tobin Brown and coworkers focuses on constructing a dynamic hydrogel environment through DMD-actuated photochemical reactions, and the study of relationship between the dynamic microenvironment and cell behavior.92 Compared to conventional methods in which the hydrogel biomaterial is used for studying the effects of matricellular interaction in vitro, photochemistry brings the possibility of capturing the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of the in vivo environment. A programmed DMD can realize spatiotemporal modulation of chemistry-reaction in real-time with precise control.

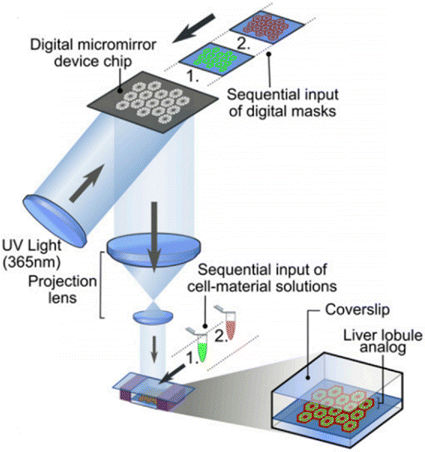

Figure 15 presents a strategy to control spatial illumination of hydrogels by DMD-based mask-less photolithography. The bioprinting method has two steps, in which the first digital mask forms the pattern of the object, while the second digital mask defines the patterning of the supporting cells.93,94

Fig. 15. Schematic diagram of a two-step 3D bioprinting approach in which hiPSC-HPCs were patterned by the first digital mask followed by the patterning of supporting cells using a second digital mask.94

Gou et al.95 used an advanced 3D printing technology, namely dynamic optical projection stereolithography (DOPsL), to inspire a 3D detoxification device by installing PDA nanoparticles in an accurate 3D matrix with modified liver lobule configuration. The DOPsL technology appropriates a coded DMD to generate dynamic photomasks to generate 3D complex structures by layer-by-layer photo-polymerization of biological materials. DOPsL has been used to create complex 3D geometric shapes of functional devices and artificial tissues with great efficiency and versatility. Through appropriate design of the masks, it is possible to build PEGDA hydrogel with precise 3D structures.

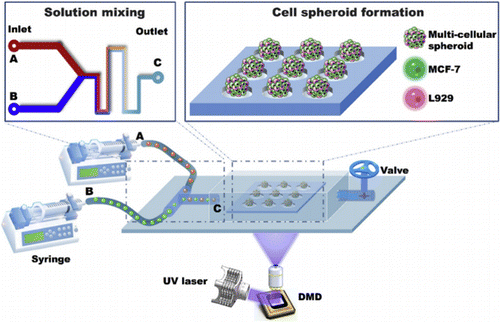

Yang with his team are currently building a complete system for maskless multicellular heterospheroids arrays hydrogel fabrication based on DMD and micro-fluidic splitters. They aim to extend the efficient tumor models in vitro for anti-cancer drug screening. In their microwell fabrication system, DMD serves as the light modulator that projects UV light frames on a microfluidic chip, as shown in Fig. 16. Drug screening test results obtained using this system showed that the multiple drugs resulted in more effective treatment, with heterospheroids exhibiting a high rate of drug resistance as compared with homospheroids.96

Fig. 16. 3D heterospheroids generation, culture and drug screening system, which consists of two function modules: microfuidic module and microwell fabricating module. Microwell fabricating system includes the following components: DMD, optical focusing system and ultraviolet (UV) laser.96

Shawn et al.97 applied DMD projection stereolithography (PSL) to the fabrication of GelMA scaffolds for the growth of meniscus tissue.98,99,100 Specified patterns for each layer of the scaffold were placed onto the DMD. While the DMD selectively reflected UV light that subsequently focused at specific locations in the photo-curable GelMA solution through a projection lens, it was possible to generate a 3D photo-cured matrix. The height of the cured layer was determined by the distance between the glass cover and the servo-controlled platform. Results from their experiments showed that micro GelMA scaffolds fabricated by DMD-PSL maintained the vitality of human meniscus cells without cytotoxicity, thus leading to possibility of reproducing organized cell arrays. The structured GelMA scaffold, prefabricated to mimic the collagen bundle tissue structure of meniscus, has become a favorable choice for meniscus repair. In contrast to other 3D patterning strategies, DMD projection printing offers advantages in terms of speed, flexibility, and scalability.

In the layer-by-layer manufacturing process, the fact that the textured image can be rapidly changed in the micromirror array means that the time required for replacing the patterned substrate and construction of the microstructure will be much shorter.101 To generate a complete layer in a single exposure can improve the extensibility of the projection stereoscopic lithography platform. A series of digital images can be sequentially loaded into the DMD driver board. The images will then be sequentially delivered to the photoresist (PR) resin to form the 3D structure through a continuous, layer-by-layer polymerization process. The principle is explained in detail with microstructure models in Ref. 102. Compared to previous DMD-based fabrication methods,103,104 a significant advantage of DMD-based optical projection stereo-lithography (DOPsL) is its mask-free operation offering significantly reduced fabrication time. In the evaluation experiments, various pattern arrays were designed to test whether microstructures modulate cell adhesion and migration. The researchers obtained evidence on the transformation of 3T3 cells after growth on PEGDMA hydrogels containing 4% paraformaldehyde under a specific structure and also studied the slow-release effects of the hydrogel.105

4. Discussion

The above elaborates on the applications of DMDs in a series of biomedical instruments. A major advantage of DMD is that it immediately brings the convenience of changing the spatial frequency with high-speed. Dual-axis spatial frequency can also be produced by varying the fringe periodicity and orientation. An aperture window can be introduced to change the spatial frequency magnitude. Compared to LCD-based SLM106,107,108,109 mentioned in Sec. 2, DMDs can work as angle-independent amplitude modulator to avoid variations in the fringe contrast and noise-like patterns. Another advantage is that DMDs can readily achieve automatic micron-level pinhole alignment to compensate drift correction through digital scanning. This is often done manually in most cases. DMD also plays a role of modulator for shaping the wavefront of light fields. On the other hand, users often criticize the low contrast ratio DMDs, especially in reflection mode, may offer because of the residual specular reflection when most of the micromirrors are in “off” state. LCD placed in the conjugate plane to attenuate the residual signal by another factor of 400. Based on the experimental results obtained from a DMD–LCD system, the feasibility of DMD–DMD combination is proposed.

Programmed patterns may work as a reflective light modulator that leads to an optimized binary compressive detection (OB-CD) strategy, which may result in highly accurate spectroscopic analysis by collecting full field of photons. DMD is more attractive for use in Raman spectroscopy at high-speed and because of higher photon throughput with polarization insensitivity, thus making it possible to conduct real-time Raman spectroscopy. Compressive Raman detection has been shown to reveal micro-calcification in breast cancer, as well as a process analytical technology (PAT) tool for real-time measurement in continuous manufacturing.

DMD-based scanning laser/light ophthalmoscopy (SLO) can perform continuous analysis of the retina in two dimensions at high-speed with confocality. DMD also offers the possibility of using various scanning methods, such as a single line scanning operated in rolling shutter mode or parallel lines with a global shutter camera. Using a DMD to design concentric circle illumination may eliminate Posterior reflection of the cornea, thus bringing SNR improvements without compromising on image quality.

The adoption of DMD in an optical system can easily achieve high-speed synthetic aperture imaging, which is often done by using galvanometer mirrors or an optical grating. Projecting Lee holograms on the DMD and placing it in a conjugate sample is an effective approach to improve power efficiency. The use of a computer-generated holograms, which may take the form of binary detour-phase, Lee hologram, and binary synthetic interferogram may open up a wide range of optical instrumentation strategies for a multitude of applications.

5. Potential Developments and Perspectives

With rapid control of the DMD device and faster cameras for detection, optical instruments with imaging frame rate increased to kHz are readily achievable.110 One can contemplate many application possibilities, particularly those relevant to healthcare technology.

In fact, it is possible to use an optimized single photodetector, in conjunction with using customized patterns, to replace the camera for high speed 2-dimensional signal capture. DMD-based computer-generated holography (CGH) should have sufficient speed to overcome the fast speckle decorrelation time required by biological samples for good focusing capability, which is often a requirement in many biomedical sensing and imaging applications.

DMD-based scanning laser/light ophthalmoscopy offers advantages in terms of stability and efficiency when used with other imaging techniques such as optical coherence tomography, and also as an auxiliary device to provide a tracking function.

The two-dimensional angular address-based array enabled by two DMDs opens up application potential as such systems can perform simultaneous functions of spatial orientation variations, pixel data extraction, and signal processing. The flexibility to adjust the interrogation angle and sensing spots according to application requirements with reliable adjustability offers a better application prospect for orientation tracking and target screening.

A programmable plasmonic phase modulator (PPPM) array based on the SPRI Kretschmann configuration incorporating a DMD and a high χ(2) dielectric thin film as the active layer can reach 1GHz modulation speed at a wavelength of 1550nm with potential applications such as discrete step beam steering or continuous beam steering. The realization of programmable spatial variable light modulation at a rate of gigahertz potentially provides a way to realize accurate ultrahigh-speed spatial light modulation.

For applications that are forthcoming, microscopes fitted with DMD and suitable image processing algorithm research can help to optimize various functional parameters. High-resolution quantitative analyses with color information will be a powerful research approach that can be adopted across many fields, such as in materials science and surface morphology. The collection of such data may lead to interdisciplinary research applications, which are otherwise not possible, including investigation of micromorphic features in taxonomy, developmental biology, functional morphology, palaeontology, and engineering.

The DMD device allows the use of rapidly interchangeable photomasks during layer-by-layer fabrication process. Compared with other 3D graphing methods, DMD projection printing has superiority in terms of speed, flexibility, and scalability. The ability of DMD Projection Printing System for producing a full layer within one exposure improves the extensibility of the projection stereolithography platform. Due to the creation of each layer by supplementing the prepolymer discontinuously, it has made it possible to develop multilayer composite 3D structures by exchanging prepolymers at various points. The utility of using DMD-PSL using GelMA for rapid production of organized artificial scaffolds supports the development of new meniscus tissue by imitating meniscus collagen bundles, which open the window of establishing an in-vitro three-dimension culture model of meniscus lesions intervertebral disc cells or other artificial organs.

6. Conclusion

The enormity and ever-expanding nature of the healthcare industry will continue to inspire new and innovative medical technologies and devices that have a significant role in all aspects of the sector. As show in this review, MEMS-based technologies have already brought impactful improvements in terms efficacy and cost savings for healthcare devices, which will in turn benefit patient care, as well as the broader scope of disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. The DMD is an array of micromirrors capable of introducing high speed, efficient, and reliable spatial light modulation. Such functionalities as a whole result in programmable, high-speed light-crafting without any mechanical movements, which is central to many of the optical instruments in the laboratory. In summary, we have gathered the key developments of this topic until now, including DMD-based microscopic imaging systems, OBCD strategy with DMD, SLO for fixational eye detection, two-dimensional angular address-based SPR sensor array and PPPM array, and the strategy of DLP maskless photolithography techniques. The high degree of spatiotemporal flexibility for creating optical patterns using DMDs makes an attractive attempt for advanced imaging systems. Adopting DMD in the system instead of using galvanometer mirrors or an optical grating can accomplish high-precision synthetic aperture imaging. The realization of programmable spatial variable light modulation will open a new avenue for the actual ultrahigh-speed spatial light modulation. DMD-based systems and the next-generation MEMS certainly hold good prospect for future medical instruments as an enabling platform.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the financial support from Hong Kong Research Grants Council through projects AoP/P-02/12, 14201317, 14210517, NSFC-RGC 81661168014 and N_CUHK407/16) and Innovative Technology Fund (ITS/061/18, GHX/004/18SZ).