Digital Leadership Competency to Enhance Digital Transformation

Abstract

The importance of leadership is increasingly recognized in relation to digital transformation. Therefore, middle management and top management must have the competencies required to lead such a transformation. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the relationship between the digital leader competencies as set out by the European e-competence framework (e-CF) and the digital transformation of organizations. Also, the relationship between digital leadership competency (DLC) and IT capability is examined. An empirical investigation is presented based on a sample of 433 respondents, analyzed using PLS-SEM. The results strongly support our hypotheses. DLC has a strong impact on organizational digital transformation. A post-hoc analysis showed this is predominantly the case for the e-CF competencies of business plan development, architecture design, and innovating while business change management and governance do not seem to affect organizational digital transformation. This is the first empirical study to conceptualize, operationalize and validate the concept of DLC, based on the e-competence framework, and its impact on digital transformation. These findings have significant implications for researchers and practitioners working on the transformation toward a digital organization.

1. Introduction

In today’s digital era organizations can no longer ignore the range of recent technologies that are available and can be used to improve or innovate their business model. Innovations such as cloud computing, social media, the Internet of Things, mobile computing, artificial intelligence, and big data analytics have the capability to completely alter the fundamentals of competition and restructure traditional industries. These key technologies will accelerate and enhance the creation, development, manufacturing, and access of revolutionary products and services [Yoo et al. (2010); Legner et al. (2017)]. Albeit the recent attention towards digital transformation, see Vial [2019] for an extensive review, research has long explored how IT can be strategically utilized to reinforce an existing business strategy [Wessel et al. (2021)]. In this research, we study the organizational perspective. An organizational digital transformation influences all the functions of the organization [Porfírio et al. (2021)] and is identified as a major springboard for product, process, and business model innovation [Bresciani et al. (2021b)]. Subsequently, due to its disruptive nature, it is increasingly incorporated and reflected in organizational strategies. This requires a digital transformation of many of the organizational operations and their accompanying management practices, which in turn also creates leadership challenges [Matt et al. (2016); Karahanna and Watson (2006); Buck et al. (2021); Adie et al. (2022)].

Legner et al. [2017] identified 10 key areas that undergo significant change when businesses attempt to become digital. A key aspect of this transformation is that middle and upper management need to improve their digital competenciesa to be able to drive digital innovation and transformation. Other scholars also stipulate the importance of transformational leadership competencies [Matt et al. (2016); Bennis (2013); Bresciani et al. (2021a)]. Prior studies have taken a business strategy perspective and are primarily conceptual [Matt et al. (2015); Correani et al. (2020); Li et al. (2016)] or case study oriented [El Sawy et al. (2016); Ivančić et al. (2019)]. Few studies have presented empirical proof that the qualities of digital leadership influence an organization’s utilization of IT and their digital transformation [Porfírio et al. (2021)]. Also, relatively little effort has been devoted to empirically investigating the relationships between the digital leadership competencies of management and digital transformation of the organization. Especially, there is an opportunity for empirically examining attitude-related elements of digital leaders in relation to digital transformation [Philip (2021)]. There is thus a paucity of literature on the role of leadership competencies. Additionally, practice-based research shows that many European organizations don’t have the correct set of competencies available to guide an organization in its digital transformation [Hüsing et al. (2013)]. Hence, a better understanding of the link between digital leadership competencies and digital transformation is necessary, and further empirical investigation is warranted.

This research seeks to investigate the connection between digital transformation leadership skills and the digital transformation of an organization, as well as explore the potential moderating role that digital leadership competencies may have on the relationship between an organization’s IT capabilities (ITCs) and digital transformation. By refining the conceptualization of digital leadership competencies and empirically validating the measures, this study provides initial empirical evidence to further our understanding of how digital leadership competencies can affect digital transformation. It is our hope that this research will catalyze discussion and expand the existing theories about the influence of digital leadership competencies on digital transformation.

This paper is structured as follows: In Secs. 2 and 3, the theoretical background to this study is described and subsequently in Sec. 4, a conceptual model is developed, and accompanying hypotheses are formulated. The data collection and analysis process are discussed in Sec. 5. Then, in Sec. 6, we present our empirical findings. In Sec. 7, we discuss and reflect on the findings, and we also offer avenues for future research. Finally in Sec. 8, conclusions are provided.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Digital leadership

El Sawy et al. [2016, p. 142] define digital leadership as “Doing the right things for the strategic success of digitalization for the enterprise and its business ecosystem”. We take a similar perspective in this study and thus take a strategic perspective on the digital transformation of the organization. Leaders are on the center-stage regarding the digital transformation phenomenon and thus play a pivotal role in this transformation. One could say that management that is involved in the digital transformation of the organization is the maestro of the digital orchestra [Wade et al. (2017)]. The very nature of this leadership is that it comes with responsibilities to guide the organization through a myriad of opportunities, identify the right value proposition and path for the organization, and drive adequate and timely change. Due to digital transformation, managers face a lot of uncertainty. However, the decision to undergo transformation will not just affect the IT function; it will have repercussions throughout the organization. Therefore, managers are often reluctant to take drastic action [Bongiorno et al. (2018)].

The relevance of leadership characteristics in relation to digital transformation is underscored by several studies [e.g. Gudergan et al. (2021)]. The effectiveness of leadership is to be found affected by characteristics like business and strategic IT knowledge, and political savviness [Smaltz et al. (2006)]. In addition, Li et al. [2006], for instance, found empirical evidence that characteristics (i.e. openness, conscientiousness, extraversion) of digital leaders significantly explain the organizational innovative usage of IT. This IT adoption is also moderated by different leadership styles [Tseng (2017)] and leadership behavior [Shao (2019)]. Little is known however on the role of competencies to provide proper digital leadership to excel at digital transformation. This study thus takes on a competence-based view of digital leadership.

2.2. Competence-based view on digital leadership

Competence-based view [Sanchez and Heene (1997)] is based upon the underpinnings of theories such as the knowledge-based view [Kogut and Zander (1992); Erickson and Rothberg (2014)], strategic assets [Amit and Schoemaker (1993)], and competitive heterogeneity [Hoopes et al. (2003)] that accentuate the need by organizations to focus on its knowledge, resources and capabilities for creating value and competitive advantage. The competence-based view, instead, goes one step further. An organization’s success compared to its peers is determined by its ability to utilize resources more effectively and/or efficiently [Freiling (2004)]. This requires action-related competencies that utilize these rather static resources in value-added activities for the organization.

A competence-based approach employs competence models to bridge the gap between individual competencies and the core abilities of an organization [Van Der Heijde and Van Der Heijden (2006)]. Competencies and skills are often used interchangeably. Sanchez [2004], for instance, refers to skills and defines them as “special forms of capability, usually embedded in individuals or teams”. Whereas Freiling and Fichtner [2010] refer to competencies as a repeatable, knowledge-based, rule-based ability to produce competitive output and stay competitive. This includes individual knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors, which are observable performance dimensions [Bratianu et al. (2020)]. Competence is thus a broader concept encompassing knowledge and attitude next to skills.

This study examines the role of digital leadership competency (DLC) in the digital transformation of organizations. It argues that DLC should not be viewed as a resource, but rather as a competency that can spur digital transformation. It further conceptualizes DLC and its dimensions in Sec. 3. This study contributes to the growing discussion on competence-based view and adds to existing research by extending the notion of digital leadership as a compound competency that has both strategic and operational implications.

2.3. IT capabilities

Where competencies are related to people, capabilities are bound to organizations and ITCs are a much-studied field of research. The theoretical underpinnings are based on resource-based view (RBV). It is theorized that organizations that perform well do so because of resources that are unique to them, scarce, and hard for competitors to copy [Bharadwaj (2000); Barney (1991)]. RBV suggests that organizations can gain a competitive advantage and superior performance by leveraging their resources, such as innovative success [Terziovski (2010)], to create value [Grant (1991)]. Over the years, the RBV proved a useful lens for a myriad of studies, including examples in the field of corporate branding [Silva et al. (2017)] and cross-border e-commerce [Elia et al. (2021)]. The theory has supported the advancement of new conceptualizations of capabilities in the field of, for instance, big data analytics [Gupta and George (2016)], and AI [Mikalef and Gupta (2021)] that has demonstrated a significant impact on performance [Ferraris et al. (2019); Rialiti et al. (2019)].

Based on the RBV theory, ITCs have been developed and recognized as a key organizational resource in both strategic management and IS literature. ITC is defined as the ability to assemble and deploy IT-based resources in combination with other organization’s resources [Bharadwaj (2000)], and is identified as a multidimensional latent variable yielding three contributing dimensions [Lu and Ramamurthy (2011); Chen et al. (2014)]. In this paper, we adopt these concepts and definitions. First, IT infrastructure capability refers to the ability to provide extensive organization-wide, robust, and integrated IT infrastructure services. This in turn enables the organization’s business processes to support value creation. IT business spanning capability stresses the connection between IT and business, allowing for quick and effective changes to business processes and information systems in order to innovate and take advantage of business opportunities. Additionally, a proactive stance toward IT serves to enable organizational learning, allowing the organization to adjust to changes in its environment [Lu and Ramamurthy (2011)].

3. Conceptualizing Digital Leadership Competency

The e-CF sets up a universal vocabulary for the capabilities, competencies, and proficiency levels of individuals throughout Europe. It supports ICT managers, human resource departments, and educational institutions in both public and private sectors as it enables the identification and definition of skills and competencies required to successfully specify organizational roles. Literature suggests that the e-CF sufficiently reflects competencies related to IT profiles [Plessius and Ravesteyn (2016)]. The CEN Workshop TC428 on ICT Skills has been supporting and working on the European Competence Framework for over 10 years, resulting in its current form. Multiple stakeholders and organizations from the European ICT sector have been involved with this effort. This ensures content validity for this construct.

The framework provides a description of 30 typical ICT professional role profiles [European Union (2021)]. The role of the Digital Transformation Leader is one of the conceptual foundations this paper is based on. This role is described as: “Provides leadership for the implementation of the digital transformation strategy of the organization” [CEN (2016)]. The framework provides the five main competencies that are crucial for managers who play a significant role in the digital transformation of the organization. These competencies are business plan development, architecture design, innovating, business change management, and governance. Each of these five competencies is defined by a description of the underlying skill and knowledge requirements as well as a description of the level to which each skill and knowledge requirement should be mastered. It is essential to clarify that while the e-CF presents the perspective of this role as a single individual, our study investigates the manifestation of competencies in general management rather than focusing solely on an individual.

3.1. Business plan development

The ability to create a business plan, including identifying potential returns and alternative approaches, as well as ensuring alignment with business and technology strategies, is known as business plan development competence. Furthermore, this skill set must also include the capability to present the business plan to key stakeholders and address the political, financial, and organizational interests of the organization. In digital transformation, digital technology (re)defines the value proposition of the organization [Wessel et al. (2021)]. A transformation of this magnitude necessitates a reassessment of the digital business strategy and the portfolio of products, businesses, and activities that are within the corporate scope of the company [Bharadwaj et al. (2013)] and formulated in a new business plan. According to a recent survey, a strategic-oriented plan should be implemented to guide and direct the digital transformation of the whole organization. The survey also revealed that digital leaders must obtain transferable and soft skills in order to foster a digital culture in the company and foster collaboration and agreement concerning the plan [Capitani (2018)].

3.2. Architecture design

The architecture can be seen as the technical foundation on which a digital business strategy relies. It describes the design of information services and how processes are taking advantage of these digital resources [Bharadwaj et al. (2013)]. The strategic role of architecture in organizations has become increasingly important in IS, management, and business and consulting circles. This is largely due to the developments that organizations have undergone in recent years, such as migration to the cloud, the introduction of analytics and AI tools, and the rationalization of legacy. Digital platforms are now ubiquitous and are revolutionizing the whole digital landscape [Reuver et al. (2018)]. For this reason, it is imperative that organizations consider the interoperability, scalability, usability, and security of their platform architectures. Its underlying modular architectures are replacing traditional monolithic approaches [Tiwana et al. (2010)]. The recent COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the value of this discipline and the role it serves in making smarter decisions [Allega (2020)]. Architecture is thus a key factor in helping organizations achieve digital transformation, as it outlines and coordinates business and IT assets and processes, as well as the connections between them [Wetering et al. (2021)].

3.3. Innovating

For organizations to survive, they must rapidly adapt to changes in their surroundings [Bharadwaj et al. (2013)]. Creative solutions can be developed to provide new concepts, ideas, products, or services, particularly through IT exploration, which involves using and combining existing technologies and resources to create new ITCs and market opportunities. An organization’s ability to detect opportunities for innovation and its digital transformation thus seems to have a symbiotic relationship [Vial (2019)]. Innovating is linked to organizational performance, and it involves exploring new ideas and using technological advancements to meet organizational needs or research goals [Nwankpa and Datta (2017)]. Experiencing and deploying novel, open thinking is part of the competency of innovating.

3.4. Business change management

Haffke et al. [2017] argued that companies must strive for ambidexterity (also known as bimodality) to be successful. This means that organizations on the one hand must maintain an operational backbone where the (traditional) IT strategy is set to enable a business strategy [Bharadwaj et al. (2013)], and on the other hand formulate and execute a digital business strategy. Especially for non-native digital organizations, this is challenging. One must possess the ability to evaluate the effects of new digital solutions and discern the possibilities brought about by new digital technologies [Sebastian et al. (2017)]. Managing change while maintaining an organization’s current business and processes to support continuity is thus likely to be a vital competence for leaders in the transformation to digital [Lin and McDonough III (2011); Jackson and Dunn-Jensen (2021); Buchwald and Lorenz (2020)].

3.5. Governance

Whilst innovating and business change management deal with the transition to a digital business strategy, governance should be in place when the transformation to digital is implemented. It is generally accepted by scholars that leaders must recognize and address all problems related to the implementation of digital transformation. This includes clearly defining organizational units and roles and policies to place decision-making responsibilities properly and to connect IT and business functions horizontally; it incorporates a set of formal structures [Wu et al. (2015); DeLone et al. (2018)]. DeLone et al. [2018] suggest that, in order for governance to be successful in a digital age, it must facilitate the collaboration of different internal and external perspectives. Therefore, the digital business strategy should be considered from a business ecosystem viewpoint [Bharadwaj et al. (2013)]. We see similar importance of governance in a platform ecosystem [Tiwana et al. (2010)].

4. Research Model and Hypotheses

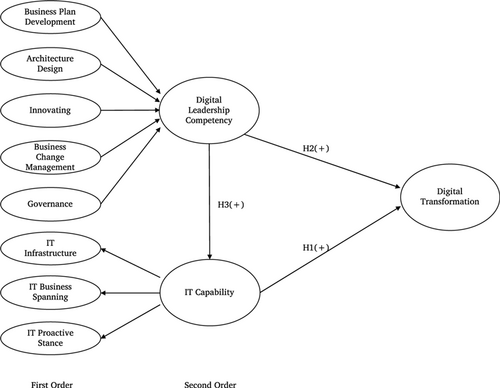

This study suggests a research model (displayed in Fig. 1) that is based on the developing body of knowledge regarding digital leadership and ITCs. This study suggests that ITCs can be represented as a second order, hierarchical model consisting of three second-order constructs: IT Infrastructure, IT Business Spanning, and IT Proactive Stance, which is in line with the literature on ITCs [e.g. Wiesböck et al. (2020)]. In addition, we propose a self-developed second-order construct of digital leader competency based on the professional role of the digital transformation leader from the e-CF role profiles that contain five competencies: Business plan development, architecture design, innovating, business change management, and governance. The term competency is used to refer to occupational underlying competencies that are in line with prior educational studies [e.g. Brockmann et al. (2009)]. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model for our research. The main proposition is that organizational digital transformation varies depending on both the digital leadership skills that are present and the level of ITCs. Table 1 provides the definitions and source references for the constructs used in this conceptual model.

Fig. 1. Research model.

| Construct | Description | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|

| IT capability | “...the extent to which a firm is good at managing its IT resources to support and enhance business strategies and processes” | Lu and Ramamurthy [2011] |

| IT infrastructure | A firm’s ability to deploy and manage a set of shareable platforms. The ability of a firm’s management to envision and exploit IT resources to support and enhance business objectives | |

| IT business spanning | A firm’s ability to proactively search for ways to embrace new IT innovations or exploit existing IT resources to address and create business opportunities | |

| IT proactive stance | A firm’s ability to deploy and manage a set of shareable platforms. The ability of a firm’s management to envision and exploit IT resources to support and enhance business objectives | |

| Digital leadership competency | Provides leadership for the implementation of the digital transformation strategy of the organization | e-CF [CEN (2016)] |

| Business plan development | Addresses the design and structure of a business or product plan including the identification of alternative approaches as well as return on investment propositions. Considers the possible and applicable sourcing models. Presents cost-benefit analysis and reasoned arguments in support of the selected strategy. Ensures compliance with business and technology strategies. Communicates and sells the business plan to relevant stakeholders and addresses political, financial, and organizational interests | |

| Architecture design | Specifies, refines, updates, and makes available a formal approach to implement solutions, necessary to develop and operate the IS architecture. Identifies change requirements and the components involved: hardware, software, applications, processes, information and technology platform. Considers interoperability, scalability, usability, and security. Maintains alignment between business evolution and technology developments | |

| Innovating | Devises creative solutions for the provision of new concepts, ideas, products, or services. Deploys novel and open thinking to envision exploitation of technological advances to address business/society needs or research direction | |

| Business change management | Assesses the implications of new digital solutions. Defines the requirements and quantifies the business benefits. Manages the deployment of change considering structural and cultural issues. Maintains business and process continuity throughout change, monitoring the impact, taking any required remedial action and refining approach | |

| Governance | Defines, deploys and controls the management of information systems in line with business imperatives. Takes into account all internal and external parameters such as legislation and industry standard compliance to influence risk management and resource deployment to achieve balanced business benefit | |

| Digital transformation | “...the changes and transformations that are driven and built on a foundation of digital technologies” | Nwankpa and Roumani [2016, p. 4] |

Recent literature provides potential agendas on digital transformation that stipulate the need for research into the relationship between ITCs and digital transformation [Vial (2019); Verhoef et al. (2021)]. Hitherto, the only empirical evidence comes from Nwankpa and Roumani [2016] that claim that companies with established ITCs are better equipped to undergo a digital transformation when they reconsider and change their current business model. Similarly, we believe that there will be a significant connection between ITC and digital transformation. To be more specific, organizations with a high level of ITC will benefit from digital transformation. In this study, we adopt the multidimensional conceptualization of ITC of Lu and Ramamurthy [2011], which modeled ITC as a latent construct reflected in three dimensions: (1) Infrastructure proficiency demonstrating the capacity to launch platforms, (2) business-wide potential revealing management’s aptitude to visualize and apply IT resources to bolster and amplify business objectives, and (3) proactive attitude indicating the capability to search for ways to incorporate new digital developments. Henceforth, we postulate the following hypothesis.

| H1. | ITC (i.e. infrastructure, business spanning, proactive stance) is positively associated with an organization’s digital transformation. | ||||

Organizations with management that score high on levels of digital leadership competencies are likely to be more confident to make radical decisions for transforming their organization digitally. They are able to both explore new value propositions and (re)formulate a digital business strategy (business plan development), create new solutions (innovating), and govern the existing organization (governance). In this ambidexterity of exploring and exploitation of IT it is likely that organizations that succeed in this balancing act will reap the benefits of the organizational digital transformation (business change management). Regarding the role of IT architecture and platforms in digital transformation, as exemplified by the case of LEGO [El Sawy et al. (2016)], it is probable that novel approaches to constructing an architecture will improve the execution of the digital business strategy, which is critical to the digital transformation of the organization.

Overall, we conceptualize digital leadership competencies as a multidimensional construct. These dimensions are based on the e-CF competencies related to the digital transformation leader job profile. Leaders who have excelled at these dimensions are likely to be more effective in their roles because they will be able to direct their organization on the path of its digital transformation. Conversely, we assume that leadership without digitalization experience and related competencies is a significant barrier to the digital transformation of the organization [El Sawy et al. (2016)]. Therefore, we hypothesize that

| H2. | DLC (i.e. business plan development, architecture design, innovating, business change management, governance) is positively associated with an organization’s digital transformation. | ||||

As illustrated in Fig. 1, we conceptualize additional relationships between digital leadership competencies and ITC. Schoemaker et al. [2018] recently stipulated the importance of the relationship between leadership and organizational capabilities. Leaders are needed to create and put into practice a variety of organizational processes that make up capabilities. Even more, they state that “strong dynamic capabilities are impossible without it” [Schoemaker et al. (2018, p. 15)]. Underdeveloped digital leadership competencies may, in fact, harm the organizational digital transformation even when the level of ITCs is high. In the decision-making process, digital leaders may make inaccurate choices when their skills are inadequate. Conversely, competencies can assist leaders in making informed decisions that can lead to more IT-enabled initiatives that bolster organizational IT abilities. Therefore, having highly developed digital leadership competencies that effectively build and strengthen ITCs could advance digital transformation.

In general, the literature suggests a strong relationship between IT governance and ITCs [Lim et al. (2012)] as IT governance entails the utilization of specific tools to achieve the desired IT abilities. Zhang et al. [2016] show an empirical association between the two constructs. Similarly, we expect a positive relationship between the competence of governance used in our research and ITC. Additionally, “going digital” requires a digital business strategy [Bharadwaj et al. (2013)], which means one must be able to anticipate and make use of IT resources to assist and strengthen business goals [Lu and Ramamurthy (2011)]. Digital leaders with extensive competencies to well-align IT and business, thus business plan development competence, can better position themselves on business–IT strategic thinking and partnership and will likely reap better digital transformation. Further, for success in digitalization, an enterprise platform that integrates well is essential [El Sawy et al. (2016)]. Up-to-date knowledge about these platforms and their underlying infrastructure combined with the organizational ability to deploy such platforms will lead to a more successful transformation into a digital organization. Lastly, digital executives who furnish their organization with the capability to proactively seek out avenues to adopt new IT inventions and possess a high degree of capability to innovate are more likely to spearhead improvements of the organizational proactive stance. We thus propose the following hypothesis.

| H3. | DLC (i.e. business plan development, architecture design, innovating, business change management, governance) is positively associated with ITCs. | ||||

5. Research Method

5.1. Measurements

We partially adopted questions and measures from earlier validated studies [Lu and Ramamurthy (2011)]. The development of the second-order constructs DLC and ITC and their respective dimensions that comprise it are depicted in Table 2. The constructs and items in the questionnaire of our study are based on previously published latent variables with psychometric properties that validate their validity and items were operationalized on a seven-point Likert scale, a widely accepted practice in large-scale empirical research, that will lead to a closer approach to the underlying distribution, therefore normality and useful as interval scales [Wu and Leung (2017)]. The seven-point Likert scale is a preferred rating scale [Preston and Colman (2000)]. We used the recommended labels by Simms et al. [2019]: “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “slightly disagree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “agree”, “slightly agree”, “strongly agree”. Appendix A lists the operationalization of all the constructs.

| Second-order | Type | First-order (sub-dimensions) | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| IT capability | Reflective | Infrastructure | Reflective |

| Business spanning | Reflective | ||

| Proactive stance | Reflective | ||

| Digital leadership competency | Formative | Business plan development | Formative |

| Architecture design | Formative | ||

| Innovating | Formative | ||

| Business change management | Formative | ||

| Governance | Formative |

ITC is represented by a second-order construct consisting of three interrelated first-order dimensions. This measurement model specification identifies the common variances or covariances shared by the three dimensions, thereby forming a covariation model among them. The three dimensions are based on the work of Lu and Ramamurthy [2011] and include IT infrastructure (assessed using three items that indicate how much a company has implemented a range of shareable platforms), IT business spanning (assessed with three items that show how well a firm’s management can visualize and use its IT resources for business objectives) and IT proactive stance (measured with four items which show how actively a firm seeks to use or take advantage of IT resources to generate business value). Consequently, and following the contemporary empirical studies [Nwankpa and Datta (2017); Lu and Ramamurthy (2011); Nam et al. (2019); Wiesböck et al. (2020)] ITC is designed as a Type I second-order construct, which means that both first-order and second-order constructs are reflective [Sarstedt et al. (2019)].

DLC is designed as a Type IV second-order construct, meaning that both first-order and second-order constructs are formative. DLC is conceptualized in accordance with the e-competencies framework [CEN (2016)]. The five underlying pillars that yield a DLC include business plan development, architecture design, innovating, business change management, and governance. In contrast to ITC, no measures exist for DLC. In order to conceptually assess whether DLC should be developed as a higher-order formative construct or as a reflective construct, we need to consider both theoretical and empirical considerations [Coltman et al. (2008); Chang et al. (2016)]. First, the nature of the construct is well reflected by formative indicators. The five dimensions are formed by their indicators rather than existing as such. Second, in the case of formative constructs, there is no necessity for indicators to covary with each other, something which is expected in the case of reflective constructs. Based on the grounding of the DLC construct, the five dimensions do not need to covary. Having developed a competence in the architecture design dimension, for example, does not necessarily mean that an organization has cultivated business change management competencies. Lastly, developing DLC as a formative construct is in line with previous literature on competencies [e.g. Ghasemaghaei et al. (2018)]. For each competence, we constructed two or three items that reflect the organizational leadership competencies and are based on the knowledge and skills examples as described by e-CF [CEN (2016)].

Digital transformation is developed in line with Nwankpa and Roumani [2016] as to what extent a firm’s performance surpasses its key competitors in terms of the usage of digital technologies. We asked respondents to evaluate the use of digital technologies to drive new business processes, realize integration, and shift of business operations. Digital technologies include social media, mobile, analytics, and the cloud.

Control variables. The size of the organization was measured as an ordinal value by the number of employees, less than 250, 250–999, 1000–4999, and above 5000. Each industry type was operationalized and included separately as a dummy variable.

5.2. Survey, administration, and data

A cross-sectional questionnaire is utilized to evaluate the conceptual model as it permits the generalizability of results, allows for replication, and has statistical power. Survey-based research is a well-documented way of accurately capturing the overall trend and recognizing relationships between variables in a sample [e.g. Straub et al. (2004)]. Data was collected by students of the Master of Innovation in European Business. The students surveyed organizations individually with clear instructions from the senior researcher leading this research. Eventually, the dataset comprised 433 respondents. From the demographic information in Table 3, we can see that our respondents came from organizations with diverse characteristics in terms of size and industry sector. Regarding the number of employees, approximately half of the sample are SMEs, meaning they have fewer than 250 employees [European Commission (2020)]. Based on the statistical classification of economic activities (NACE) [European Commission (2008)] respondents were asked to indicate the organization’s primary industry. The results show that the sample is somewhat skewed toward IT organizations.

| Sample (N=433N=433) | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Firm size (number of employees) | ||

| Less than 250 | 222 | 51.3% |

| 250–999 | 75 | 17.3% |

| 1000–4999 | 24 | 5.5% |

| Above 5000 | 112 | 25.9% |

| Industry | ||

| Product industry | 71 | 16.4% |

| Transport and trade | 14 | 3.2% |

| Accommodation and food service activities | 35 | 8.1% |

| Information and communication | 110 | 25.4% |

| Financial, insurance and real estate activities | 49 | 11.3% |

| Professional, scientific, and technical activities | 72 | 16.6% |

| Administrative and support service activities | 27 | 6.2% |

| Public administration, education, and health | 17 | 3.9% |

| Other services | 38 | 8.8% |

To test for non-response bias, a wave analysis is conducted [Armstrong and Overton (1977)]. The first and last waves of respondents on all the variables are compared, which treats late respondents as a proxy of non-respondents. We found no statistically significant differences (p<0.01p<0.01). Hence, we conclude that there is no critical degree of non-response bias.

Given that all data was gathered from a single source at one point in time and that all data were reflections of key respondents, we implemented procedural controls (ex-ante) during the design of the survey [Podsakoff et al. (2012)] We ensured respondents that the information they provided would remain anonymous and confidential, gave clear instructions, avoided complex and ambiguous items, and clarified that any analysis would be performed on an aggregate level solely for research purposes. In addition, Harman’s one-factor test was used as a statistical control (ex-post). The results demonstrate that 63.5% of the variance was explained by one single factor. Recent literature [Fuller et al. (2016)] suggests that Harman’s test can result in false positives and false negatives, and the possibility for a false positive conclusion is particularly high when scale reliability is high (>0.90>0.90). Since this is the case in our study (see Table 4), the explained variance should not exceed 70% or more to avoid inflated relationships. Consequently, we infer that common method bias is not a serious issue in this research.

6. Results

Partial least structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is utilized to assess the measurement model and examine the structural model. PLS-SEM is preferred as it has few requirements on the measures used [Gefen et al. (2000)], and on the distribution of the data [Chin (1998)]. It also allows the examination of multiple associations between different independent variables and different dependent variables at the same time [Hair et al. (2011)]. Moreover, the focus of our study is on prediction and theory development rather than theory testing, which also makes PLS-SEM favored above the covariance-based SEM [Reinartz et al. (2009)]. PLS-SEM is also the preferred approach when formative constructs are included in the structural model [Hair et al. (2019)].

A bootstrap method was utilized to calculate path coefficients for statistical hypothesis testing. We investigate the measurement model to assess its reliability and validity by means of the software SmartPLS [Ringle et al. (2015)]. After this, hypotheses are examined by testing the structural model. We report the metrics according to the latest guidelines [Hair et al. (2019)].

6.1. Measurement model

Our model comprises reflective as well as formative constructs. In line with Hair et al. [2019], we used different assessment criteria to evaluate the constructs. We performed reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity tests on reflective latent constructs. The values are presented in Table 4. We first evaluate the measurement model’s internal consistency reliability. All Cronbach’s alphas and composite reliabilities were above the threshold of 0.70, suggesting a satisfactory level of construct reliability. Second, the convergent validity of the constructs is evaluated. The average variance extracted (AVE) is at least 0.50 which demonstrates sufficient results. Thirdly, the discriminant validity of the constructs is evaluated in three ways: Fornell–Larcker criterion, cross-loadings, and the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The findings show that the square root of the AVE of a construct was higher than its correlations with other constructs. Discriminant validity is thus shown through the Fornell–Larcker criterion. To assess discriminant validity, we use the HTMT ratio of correlations, as recommended by the latest guidelines. The indicator loadings for each construct also show greater values than their cross-loadings with other constructs, indicating discriminant validity. Henseler et al. [2015] strongly advocate for the use of this approach. In order to clearly differentiate between the two factors, the HTMT should be less than 0.90 [Henseler et al. (2016)]. The obtained correlations (see Table 5) comply with that criterion; thus discriminant validity is demonstrated. In summary, the results indicate that first-order reflective measures are valid for use and support the appropriateness of all items as good indicators for their corresponding constructs.

| A3 | A5 | A9 | E7 | E9 | INF | BS | PS | DT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3 | Business plan development | n/a | ||||||||

| A5 | Architecture design | 0.787 | n/a | |||||||

| A9 | Innovating | 0.758 | 0.719 | n/a | ||||||

| E7 | Business change management | 0.768 | 0.771 | 0.773 | n/a | |||||

| E9 | Governance | 0.640 | 0.647 | 0.563 | 0.662 | n/a | ||||

| INF | Infrastructure | 0.629 | 0.643 | 0.545 | 0.601 | 0.618 | 0.856 | |||

| BS | Business spanning | 0.753 | 0.718 | 0.672 | 0.682 | 0.599 | 0.666 | 0.910 | ||

| PS | Proactive stance | 0.723 | 0.700 | 0.740 | 0.678 | 0.522 | 0.609 | 0.754 | 0.908 | |

| DT | Digital transformation | 0.655 | 0.647 | 0.615 | 0.622 | 0.529 | 0.561 | 0.608 | 0.644 | 0.926 |

| Mean | 5.04 | 4.88 | 5.00 | 4.98 | 4.79 | 5.18 | 5.00 | 5.35 | 1.18 | |

| Standard deviation | 1.45 | 1.49 | 1.59 | 1.49 | 1.66 | 1.39 | 1.48 | 1.46 | 1.56 | |

| AVE | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.733 | 0.828 | 0.824 | 0.858 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.879 | 0.931 | 0.928 | 0.917 | |

| Composite reliability | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.917 | 0.951 | 0.949 | 0.948 |

| BS | INF | PS | DT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS | Business spanning | ||||

| INF | Infrastructure | 0.732 | |||

| PS | Proactive stance | 0.810 | 0.668 | ||

| DT | Digital transformation | 0.658 | 0.620 | 0.696 |

For formative latent constructs, we first examine potential collinearity issues. The variance inflation factor (VIF) is commonly used to assess collinearity among formative indicators. If the VIF values are 5 or higher, it indicates significant collinearity issues among the indicators of formatively measured constructs [Hair et al. (2019)]. Table 6 shows the VIF values of the measures used, which show satisfactory values below this threshold. Hence, this suggests that collinearity was not a major issue in the study. Second, we assessed the measures’ weights and respective significance levels. All the weights present satisfactory significance levels except one. For the construct DLC, the measure Business Change Management was marked as non-significant. Nevertheless, if an indicator weight is not significant, it does not necessarily imply poor quality of the measurement model [Cenfetelli and Bassellier (2009)]. In such cases, the absolute contribution of the indicator to the construct is evaluated instead. This contribution is reflected by its loadings. Hair et al. [2017] suggest one should consider deleting the indicator when loadings show a value below 0.50, when the weight is non-significant. Based on the fact that the loading of Business Change Management is above this threshold (0.871), we can conclude that this measure considerably contributes to the construct. Therefore, we deemed it necessary not to remove any items as each made a unique contribution to the overall construct it was assigned to.

| Construct | Measures | VIF | Weight | Significance | Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business plan development | A3.1 | 2.149 | 0.226 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.822 |

| A3.2 | 2.671 | 0.311 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.890 | |

| A3.3 | 2.521 | 0.566 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.950 | |

| Architecture design | A5.1 | 3.200 | 0.358 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.924 |

| A5.2 | 3.284 | 0.338 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.922 | |

| A5.3 | 3.171 | 0.386 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.929 | |

| Innovating | A9.1 | 2.625 | 0.707 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.977 |

| A9.2 | 2.625 | 0.343 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.900 | |

| Business change management | E7.1 | 2.864 | 0.467 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.938 |

| E7.2 | 3.404 | 0.419 | p<0.001p<0.001 | 0.938 | |

| E7.3 | 2.786 | 0.196 | p<0.001 | 0.862 | |

| Governance | E9.1 | 3.202 | 0.550 | p<0.001 | 0.961 |

| E9.2 | 3.202 | 0.496 | p<0.001 | 0.952 | |

| Digital leadership competency | Business plan development | 3.589 | 0.357 | p<0.001 | 0.931 |

| Architecture design | 3.375 | 0.305 | p<0.001 | 0.912 | |

| Innovating | 3.030 | 0.231 | p<0.001 | 0.870 | |

| Business change management | 3.682 | 0.096 | n.s. | 0.871 | |

| Governance | 1.994 | 0.133 | p<0.05 | 0.752 |

6.2. Structural model

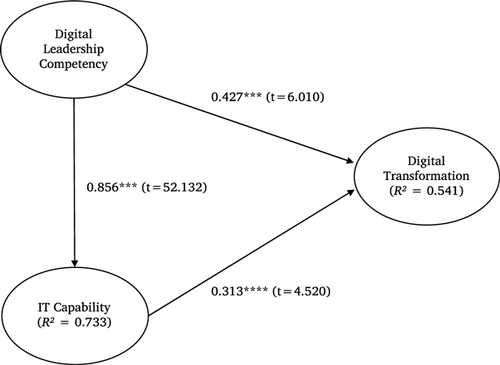

The explanatory power (R2) is examined (see Fig. 2). R2 measures the variance which is explained in each of the endogenous constructs. The structural model explains 54.1% of the variance in the main endogenous construct in our model, digital transformation (R2=0.541). In addition, the model explains 73.3% of variance for ITC (R2=0.733). These coefficients of determination represent moderate, respectively, high predictive power [Hair et al. (2019)]. R2 however only indicates the model’s in-sample explanatory power [Shmueli (2010)]. To assess the model’s out-of-sample predictive power, Shmueli et al. [2016] developed a holdout-sample-based procedure that generates case-level predictions on an item or a construct level to reap the benefits of predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM. To assess the predictive power of the model we executed a k-fold cross-validation with PLSpredict. The first step is to check whether Q2 values are above zero which indicates that the model outperforms the most naïve predicted benchmark [Shmueli et al. (2019)]. This is the case for all the indicators in the dataset used in our study (see C). The second step is to compare root mean squared error (RMSE) against the naïve linear regression model (LM) benchmark. An increasingly higher number of indicators that yield lower prediction errors in terms of RMSE when comparing the PLS-SEM analysis to the naïve LM benchmark shows a higher predictive power [Shmueli et al. (2019)]. Concerning ITC, some PLS-SEM RMSE values are higher than LM RMSEs. However, the majority of PLS-SEM RMSE’s values are lower. This indicates that the model has a medium predictive power [Shmueli et al. (2019)]. Comparing RMSEs with regard to the dependent variable digital transformation presents all indicators that yield a lower prediction error in the PLS-SEM analysis. This indicates that the model has a high predictive power [Shmueli et al. (2019)].

Fig. 2. Path coefficients and explanatory power of the structural model.

The path coefficients, and significance of estimates (t-statistics), are determined by conducting a bootstrap analysis using 5000 resamples. Figure 2 presents the estimates (standardized path coefficients, t-values, and their corresponding significance level) obtained via the PLS-SEM analysis. The results reveal a significant influence of both ITCs and DLC on digital transformation (β=0.427, t=6.010, p<0.001; β=0.313, t=4.520, p<0.001). Hence, H1 and H2 are supported. In addition, we found a significant positive relation between digital leadership competencies and ITCs (β=0.856, t=52.132, p<0.001). Consistent with other studies, we also examined the influence of control variables. Both size and industry were found to be non-significant in all cases in their relationship with the dependent variable, digital transformation.

6.3. Post-hoc analysis

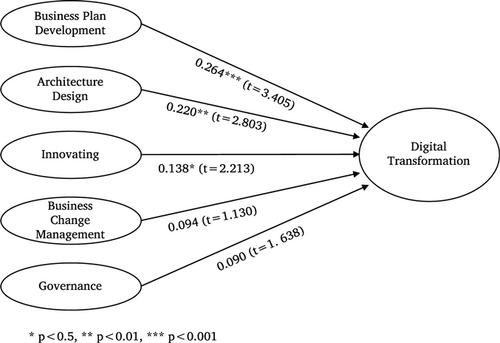

In our research, we primarily focused on exploring the relationship between DLC, Information Technology Capability, and digital transformation. However, during the analysis of the study results, we made noteworthy observations regarding the direct associations between the individual components of DLC and digital transformation. To gain deeper insights into the impact of DLC on digital transformation, we conducted a post hoc analysis. This analysis involved examining the separate and direct effects of the five digital leadership competencies on digital transformation. The findings from this analysis were enlightening and provided valuable insights into the specific contributions of each competency to the process of digital transformation (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Path coefficients of digital leadership competencies on digital transformation.

Among the five digital leadership competencies, namely business plan development, architecture design, innovating, business change management, and governance, we found that three competencies had a statistically significant and strong influence on digital transformation. These competencies were business plan development, architecture design, and innovating. Business plan development emerged as a powerful and influential factor in driving digital transformation. This competency involves the formulation of comprehensive and effective strategies to leverage digital technologies to achieve organizational goals and objectives. Companies that excel in business plan development are more likely to experience successful digital transformation initiatives. Architecture design also exhibited a significant impact on digital transformation. This competency refers to the ability to create a robust and scalable digital infrastructure that supports the implementation of digital initiatives. Organizations that possess strong architecture design capabilities are better equipped to navigate the complexities of digital transformation and achieve better outcomes. The third competency, innovating, played a crucial role in driving digital transformation. Innovating, in the context of digital leadership, encompasses the capacity to foster a culture of innovation and experimentation, leading to the development of cutting-edge digital solutions and services. Companies that foster a culture of innovation are more likely to adapt swiftly to the evolving digital landscape and gain a competitive advantage through successful digital transformation. Interestingly, we found that two of the digital leadership competencies, business change management, and governance, did not exhibit a statistically significant influence on digital transformation. This implies that these competencies might have a comparatively lesser impact on the overall success of digital transformation initiatives.

7. Discussion

The results, as shown in Fig. 3, support the claim of the positive impact of ITCs on digital transformation (H1). These results are consistent with previous research that empirically examined this relationship, such as Nwankpa and Roumani [2016]. Another interesting finding, related to H2, is that DLC significantly affects the digital transformation of the organization. This result shows empirical support for hitherto anecdotal evidence regarding the impact of digital leadership on digital transformation [e.g. El Sawy et al. (2016)]. Moreover, this study (H3) confirmed the suggested relationship between digital leadership and ITCs in the literature [Schoemaker et al. (2018)] by finding a significant result between the two constructs.

7.1. Implications for theory

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, this research contributes to the body of literature concerning ITCs. Our study confirms the findings of Nwankpa and Roumani [2016], who also found a significant relationship between the three ITCs and digital transformation. While research on ITCs has a rich history in the information systems literature, studies on the role of digital leadership in relation to ITCs are limited. Just recently Schoemaker et al. [2018] stipulated the importance of the relationship between leadership and organizational capabilities. Yet, this is an understudied area of research. Our study provides a steppingstone to examine this further and to untangle the role of digital leadership competencies in ITCs.

Second, it enriches the body of knowledge about the role of digital leadership. Where prior studies stipulated the importance of leadership in the digital era [El Sawy et al. (2016); Ivančić et al. (2019)], this is the first study that empirically found evidence for a significant relationship between digital leadership competencies and digital transformation of the organization. Our results provide empirical evidence for our main proposition that digital leadership competencies explain a significant proportion of variance in organizational digital transformation. Moreover, results show that certain competencies also affect ITCs. The significant explanatory power of digital leadership competencies underscores the importance of the competencies in influencing digital transformation. In general, the findings add to the debate on the role of leadership in the organizational digital transformation [Karahanna and Watson (2006)].

Third, in the light of explaining digital transformation by leadership, we must examine digital leadership competencies. Prior research showed the relevance of personality traits and demographic characteristics of digital leaders [Li et al. (2006)]. Also, democratic leadership styles favor the enhancement of digital transformation [Porfírio et al. (2021)]. The results of our study show the significance of competencies in addition to these characteristics and styles. This empirically supports conceptual research [e.g. Matt et al. (2015)], that stipulated the importance of leadership skills in digital transformations of organizations.

Fourth, it provides a deeper understanding of which competencies matter as our research details the construct of competencies that are relevant for digital leaders. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that scrutinized, operationalized, and empirically validated the role of the e-CF. Our research thus provides an instrument of digital leadership competencies based on this expert-driven framework.

Fifth, in the further analysis we found surprisingly that not all the dimensions of DLC enhance digital transformation. DeLone et al. [2018] stipulated the importance of governance in integrating digital initiatives into the company’s DNA. Conversely, we found the competencies of business change management and governance do not significantly influence digital transformation.

7.2. Implications for practice

The findings of this research hold significant practical implications for organizations that are contemplating embarking on a digital transformation journey. Given the growing importance of digital transformation and the substantial investments made by many organizations in digital technologies, managers must recognize the crucial role played by digital leadership competencies in ensuring the success of such transformative initiatives.

The study’s results clearly demonstrate that these digital leadership competencies play a pivotal role in driving digital transformation success. They account for a substantial portion of the variance in the outcome of digital transformation efforts, underscoring their importance in the process. Therefore, managers and leaders should prioritize the development and enhancement of these competencies within their organizations to improve their chances of achieving successful digital transformation outcomes.

For organizations aspiring to gain a competitive advantage by becoming digitally driven enterprises, it becomes imperative to recruit and nurture managers who possess strong educational qualifications and expertise in digital leadership. Leaders with competencies in business plan development, architecture design, and innovating can significantly contribute to a smooth and effective transition into the digital realm. Investing in the development of these competencies among management teams can serve as the foundation necessary to drive and sustain digital transformation across the organization.

To effectively enhance the organization’s social capital and foster a culture conducive to digital transformation, it is crucial to prioritize training and development programs aimed at improving employees’ digital leadership competencies. In this regard, the e-CF emerges as a valuable tool for benchmarking and selecting appropriate educational programs. This framework provides a structured approach to identify and assess the relevant digital leadership competencies required to thrive in the digital age. Organizations can leverage the framework to identify suitable courses and training programs that align with their specific digital transformation goals and effectively enhance the right set of competencies among their workforces.

The implications drawn from this research emphasize the strategic importance of digital leadership competencies in driving successful digital transformation initiatives. Organizations that prioritize the development of these competencies within their leadership teams and workforce are better positioned to navigate the challenges and complexities of digital transformation, ensuring a more seamless and successful transition into the digital future. By aligning educational programs with the e-CF, organizations can systematically elevate their digital leadership capabilities and, in turn, drive positive and transformative changes throughout the organization.

8. Conclusions

This study focused on an important gap in research by providing theoretical and empirical evidence of a significant relationship between DLC, ITCs, and organizational digital transformation. We relied on the seminal work of Lu and Ramamurthy [2011] to examine ITCs in relation to digital transformation. To define and validate DLC, we adopted the much-used e-CF. This approach to scientifically validate role profiles from the e-CF is, to our knowledge, a first. DLC is formulated as a multidimensional formative construct. The findings of this study demonstrate the relevance of DLC (i.e. business plan development, architecture design, innovating, business change management, governance) for enhancing ITCs and digital transformation. Such significant impact suggests that improvement in DLC will result in improving organizational digital transformation. These results have significant implications for the practice of digital transformations in organizations. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first study that attempted to empirically examine the relationship between ITCs, DLC, and digital transformation. Research hitherto has been conceptual, or case study oriented.

For organizations struggling with digital leadership, this study showed the relevance of the e-CF as a useful instrument to re- and upskill management. An increasing number of educational organizations adopt this framework as the standard for curriculum development. This helps organizations ease the incorporation of digital leadership. The significance of business plan development as a key competence, which ensures compliance with business and technology strategies, stipulates that there is still a need for strategic alignment [Henderson and Venkatraman (1992)]. In combination with competencies in innovating and understanding the design of adequate architecture, it is likely that organizations excel in digital transformation.

8.1. Limitations and future research

As with any empirical study, our work has limitations that should be recognized. First, our model comprised limited key constructs in relation to digital transformation. Other factors like financial resources, process performance, or the culture of the organization potentially influence digital transformation. Future research could examine a more comprehensive model. Second, although we utilized prior research for the operationalization of digital transformation, it is mainly focused on the use of technology. Anecdotal research however argues for a more multidimensional approach to this concept. Westerman et al. [2014] postulate three major building blocks of digital transformation, i.e. customer experience, operational processes, and business models. This field of research should benefit from a validated operationalization of this construct for future reference. Third, we must stipulate the representativeness of the sample. The limited number of respondents is not only skewed to SMEs but also not well distributed over sectors. Hence, the conclusions must be interpreted with caution. Future research might extend the dataset with subjects in order to increase the reliability and validity of our study.

Appendix A. Measurements

| Measure | Item | |

|---|---|---|

| Digital leadership competency | ||

| Business plan development | A3.1 | We exploit specialist knowledge to provide analysis of market environment |

| A3.2 | We provide leadership for the creation of an information system strategy that meets the requirements of the business (e.g. distributed, mobility-based) and includes risks and opportunities | |

| A3.3 | We constantly apply strategic thinking and organizational leadership to exploit the capability of Information Technology to improve the business | |

| Architecture design | A5.1 | We exploit specialist knowledge to define relevant ICT technology and specifications to be deployed in the construction of multiple ICT projects, applications, or infrastructure improvements |

| A5.2 | We act with wide ranging accountability to define the strategy to implement ICT technology compliant with business need and take account of the current technology platform, obsolescent equipment, and latest technological innovations | |

| A5.3 | We constantly provide ICT strategic leadership for implementing the enterprise strategy. Applying strategic thinking to discover and recognize new patterns in vast datasets and new ICT systems, to achieve business savings | |

| Innovating | A9.1 | We constantly apply independent thinking and technology awareness to lead the integration of disparate concepts for the provision of unique solutions |

| A9.2 | We constantly challenge the status quo and provide strategic leadership for the introduction of revolutionary concepts | |

| Business change management | E7.1 | We constantly evaluate change requirements and exploit specialist skills to identify possible methods and standards that can be deployed |

| E7.2 | We provide leadership to plan, manage, and implement significant ICT led business change | |

| E7.3 | We apply pervasive influence to embed organizational change | |

| Governance | E9.1 | We provide leadership for IS governance strategy by communicating, propagating, and controlling relevant processes across the entire ICT infrastructure |

| E9.2 | We constantly define and align the IS governance strategy incorporating it into the organization’s corporate governance strategy. Adapting the IS governance strategy to take into account new significant events arising from legal, economic, political, business, technological or environmental issues | |

| IT capabilities | ||

| Infrastructure | ITCI.1 | Data management services & architectures (e.g. databases, data warehousing, data availability, storage, accessibility, sharing, etc.) |

| ITCI.2 | Network communication services (e.g. connectivity, reliability, availability, LAN, WAN, etc.) | |

| ITCI.3 | Application portfolio & services (e.g. ERP, ASP, reusable software modules/components, emerging technologies, etc.) | |

| ITCI.4 | IT facilities’ operations/services (e.g. servers, large-scale processors, performance monitors, etc.) | |

| ITCB.1 | Developing a clear vision regarding how IT contributes to business value | |

| Business spanning | ITCB.2 | Integrating business strategic planning and IT planning |

| ITCB.3 | Enabling functional area and general management’s ability to understand value of IT investments | |

| ITCB.4 | Establishing an effective and flexible IT planning process and developing a robust IT plan | |

| Proactive stance | ITCP.1 | We constantly keep current with new information technology innovations |

| ITCP.2 | We are capable of and continue to experiment with new IT as necessary | |

| ITCP.3 | We have a climate that is supportive of trying out new ways of using IT | |

| ITCP.4 | We constantly seek new ways to enhance the effectiveness of IT use | |

| Digital transformation | DT.1 | Our firm is driving new business processes built on technologies such as big data, analytics, blockchain, cloud, mobile, and social media platforms |

| DT.2 | Our firm integrates digital technologies such as social media, big data, analytics, blockchain, cloud, and mobile technologies to drive change | |

| DT.3 | Our business operations is shifting toward making use of digital technologies such as big data, analytics, blockchain, cloud, mobile, and social media platforms |

Appendix B. Cross-Loadings

| A3 | A5 | A9 | E7 | E9 | BS | INF | PS | DT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3.1 | 0.822 | 0.661 | 0.607 | 0.609 | 0.530 | 0.592 | 0.507 | 0.568 | 0.564 |

| A3.2 | 0.890 | 0.723 | 0.676 | 0.726 | 0.635 | 0.689 | 0.578 | 0.648 | 0.542 |

| A3.3 | 0.950 | 0.730 | 0.725 | 0.715 | 0.571 | 0.716 | 0.592 | 0.695 | 0.634 |

| A5.1 | 0.710 | 0.924 | 0.652 | 0.685 | 0.579 | 0.650 | 0.596 | 0.651 | 0.619 |

| A5.2 | 0.730 | 0.922 | 0.665 | 0.711 | 0.601 | 0.669 | 0.589 | 0.652 | 0.590 |

| A5.3 | 0.744 | 0.929 | 0.680 | 0.740 | 0.615 | 0.673 | 0.599 | 0.642 | 0.588 |

| A9.1 | 0.748 | 0.705 | 0.977 | 0.744 | 0.558 | 0.652 | 0.541 | 0.712 | 0.601 |

| A9.2 | 0.666 | 0.644 | 0.900 | 0.718 | 0.490 | 0.615 | 0.474 | 0.688 | 0.554 |

| E7.1 | 0.725 | 0.706 | 0.739 | 0.938 | 0.614 | 0.631 | 0.558 | 0.626 | 0.595 |

| E7.2 | 0.712 | 0.738 | 0.702 | 0.938 | 0.617 | 0.652 | 0.574 | 0.642 | 0.578 |

| E7.3 | 0.670 | 0.673 | 0.683 | 0.862 | 0.595 | 0.585 | 0.510 | 0.594 | 0.521 |

| E9.1 | 0.613 | 0.608 | 0.524 | 0.642 | 0.961 | 0.573 | 0.606 | 0.502 | 0.518 |

| E9.2 | 0.612 | 0.631 | 0.555 | 0.623 | 0.952 | 0.573 | 0.575 | 0.497 | 0.494 |

| ITCB.1 | 0.679 | 0.642 | 0.624 | 0.613 | 0.531 | 0.900 | 0.579 | 0.713 | 0.596 |

| ITCB.2 | 0.712 | 0.661 | 0.626 | 0.627 | 0.508 | 0.926 | 0.580 | 0.684 | 0.589 |

| ITCB.3 | 0.677 | 0.650 | 0.587 | 0.628 | 0.561 | 0.905 | 0.623 | 0.661 | 0.518 |

| ITCB.4 | 0.674 | 0.661 | 0.609 | 0.617 | 0.582 | 0.910 | 0.642 | 0.686 | 0.508 |

| ITCI.1 | 0.554 | 0.587 | 0.511 | 0.545 | 0.538 | 0.601 | 0.870 | 0.550 | 0.506 |

| ITCI.2 | 0.495 | 0.493 | 0.446 | 0.491 | 0.509 | 0.532 | 0.835 | 0.495 | 0.402 |

| ITCI.3 | 0.595 | 0.596 | 0.510 | 0.556 | 0.547 | 0.627 | 0.867 | 0.576 | 0.555 |

| ITCI.4 | 0.502 | 0.515 | 0.388 | 0.457 | 0.521 | 0.508 | 0.853 | 0.452 | 0.446 |

| ITCP.1 | 0.681 | 0.663 | 0.687 | 0.608 | 0.521 | 0.702 | 0.573 | 0.878 | 0.581 |

| ITCP.2 | 0.691 | 0.661 | 0.684 | 0.603 | 0.491 | 0.702 | 0.585 | 0.926 | 0.607 |

| ITCP.3 | 0.582 | 0.576 | 0.638 | 0.578 | 0.410 | 0.636 | 0.481 | 0.898 | 0.520 |

| ITCP.4 | 0.665 | 0.637 | 0.674 | 0.667 | 0.469 | 0.692 | 0.564 | 0.927 | 0.625 |

| DT.1 | 0.579 | 0.571 | 0.550 | 0.541 | 0.503 | 0.569 | 0.492 | 0.577 | 0.914 |

| DT.2 | 0.633 | 0.610 | 0.607 | 0.599 | 0.492 | 0.558 | 0.541 | 0.626 | 0.941 |

| DT.3 | 0.605 | 0.616 | 0.551 | 0.586 | 0.476 | 0.563 | 0.525 | 0.587 | 0.923 |

Appendix C. PLSpredict Assessment of Manifest Variables

| PLS-SEM | LM | PLS-SEM-LM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Q2predict | RMSE | RMSE | RMSE |

| ITCB1 | 0.500 | 1.095 | 1.119 | −0.024 |

| ITCB2 | 0.526 | 1.091 | 1.112 | −0.021 |

| ITCB3 | 0.502 | 1.080 | 1.093 | −0.013 |

| ITCB4 | 0.514 | 1.087 | 1.099 | −0.012 |

| ITCI1 | 0.377 | 1.181 | 1.170 | 0.011 |

| ITCI2 | 0.292 | 1.226 | 1.233 | −0.007 |

| ITCI3 | 0.401 | 1.267 | 1.287 | −0.020 |

| ITCI4 | 0.285 | 1.364 | 1.346 | 0.018 |

| ITCP1 | 0.530 | 1.057 | 1.069 | −0.012 |

| ITCP2 | 0.526 | 1.060 | 1.063 | −0.003 |

| ITCP3 | 0.405 | 1.213 | 1.201 | 0.012 |

| ITCP4 | 0.502 | 1.073 | 1.058 | 0.015 |

| DT.1 | 0.381 | 1.324 | 1.335 | −0.011 |

| DT.2 | 0.445 | 1.222 | 1.239 | −0.017 |

| DT.3 | 0.414 | 1.248 | 1.249 | −0.001 |

ORCID

Guido Ongena  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3699-7178

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3699-7178

Paul Morsch  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3376-9708

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3376-9708

Pascal Ravesteijn  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1888-4222

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1888-4222

Note

a In academic literature the term skills is often used. In line with the European e-competence framework (e-CF), we favor the term competence as this is a broader concept encompassing knowledge and attitude next to skills [Wade and Obwegeser (2019); CEN (2016)].

Guido Ongena is a professor and program director the HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht. He has an MSc in Business Informatics from the Utrecht University (2007) and a PhD from the University of Twente (2013). His research interests include quantitative research, technology adoption and social network analysis. He is specifically focused on the application of big data analytics. His research is published in several international journals and conferences, including Business Process Management Journal, Behaviour and Information Technology, Information Research, Telematics and Informatics.

Paul Morsch is a PhD candidate within the research group Process Innovation and Information Systems at the University of Applied Sciences in Utrecht. He also teaches the course ‘Digital Leadership’ at the same university. In his research he focuses on the specific competences that organizations need in a rapidly changing and digitally transforming world to be ‘future-proof’. He has a master's degree in computer science and in human resource management.

Pascal Ravesteijn is a professor of Process Innovation and Information Systems within the research center for Digital Business and Media at HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht. Throughout his career he has always worked on the boundary between Business and IT. This is reflected in his current research interests and projects that mainly focus on IT-driven business & process model innovation and the subsequent competences and skills that employees need to be effective in a digital environment. In regard to the latter Pascal has been involved with researching the adoption and implementation of e-CF in the Netherlands since 2012. Pascal is a member of the board of directors of the International Information Management Association (IIMA) and the editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Information Technology and Management.