Implementation and application of FRET–FLIM technology

Abstract

With the development of the new detection methods and the function of fluorescent molecule, researchers hope to further explore the internal mechanisms of organisms, monitor changes in the intracellular microenvironment, and dynamic processes of molecular interactions in cells. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) describes the energy transfer process between donor fluorescent molecules and acceptor fluorescent molecules. It is an important means to detect protein–protein interactions and protein conformation changes in cells. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) enables noninvasive measurement of the fluorescence lifetime of fluorescent particles in vivo. The FRET–FLIM technology, which is use FLIM to quantify and analyze FRET, enables real-time monitoring of dynamic changes of proteins in biological cells and analysis of protein interaction mechanisms. The distance between donor and acceptor and their respective fluorescent lifetime, which are of great importance for studying the mechanism of intracellular activity can be obtained by data analysis and algorithm fitting.

1. Introduction

With the continuous developments in optical technologies, particularly the introduction of fluorescence microscopy, biological images can be obtained at the cellular and subcellular levels. This raises concerns about changes in cells and their internal environments. Researchers are beginning to focus on exploring the dynamic processes of proteins, DNA and RNA.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a process via which excited donor fluorescent molecules excite nearby acceptor fluorescent molecules through energy transfer. There are some requirements for FRET: first, the distance between donor and acceptor should be less than 10nm; second, the emission spectrum of donor overlaps with the excitation spectrum of acceptor; third, there is no overlap between the emission spectrum of donor and acceptor; fourth, there is no overlap between the excitation spectrum of donor and acceptor; fifth, the dipole of donor and acceptor should have the same direction. Moreover, FRET is also affected by the nature of the proteins. It is only possible when the distance between the donor and acceptor molecules is less than 10nm; therefore, FRET can be used to study protein–protein interactions. Yeast two-hybrid system, Western blot and Co-Immunoprecipitation are traditional means in detecting the interaction between biomoleculars. However, these methods destroy the natural state of cells, fail to conduct protein subcellular localization and reflect the spatio-temporal dynamic information of protein–protein interactions under the physiological conditions of living cells. Hence, FRET is unique and indispensable to measure small distances between biomolecules. There are two conventional FRET measurement technologies: fluorescence intensity-based method (FIBM) and fluorescence lifetime-based method (FLBM). FIBM is the most straightforward; however, it is strongly dependent on the concentration of the sample and requires calibration for reliable data analysis. In contrast, FLBM provides absolute light measurements. Fluorescence-lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) belongs to the method of FIBM. FLIM can detect the lifetime of fluorescent molecules in a single cell. Besides, fluorescence lifetime imaging of fluorescent proteins is an effective quantitative tool for noninvasive study of intracellular processes. The proportion of donor–receptor interaction can be determined by using FLIM to quantify FRET, which is important for biologically relevant research.

FRET–FLIM technology uses the fluorescence lifetime change of a sample to detect the dynamic process of the reaction between the donor and acceptor fluorescent molecules. It can obtain lots of information, such as intracellular protein–protein interactions and conformational changes to proteins in the cells.1,2,3,4,5,6

In the past three or four decades, FRET–FLIM technology has been used to evaluate various intracellular processes such as analysis of kinase and phosphatase activity, monitoring of messenger RNA kinetics, and assessment of metabolic processes.7,8,9 Nowadays, researchers gradually realized that FRET–FLIM technology can solve more biophysical and biochemical issues. Using FRET–FLIM technology, Ahmed et al.10 observed direct interaction between S6K1 and raptor; Venditti et al.11 searched for molecular determinants of the ER-TGN contact sites (ERTGoCS) and found that both structural tethers and a proper lipid composition are needed for ERTGoCS integrity; Dikovskaya et al.12 improved the FLIM/FRET methodology to visualize and measure the interaction between Nrf2 and Keap1 in single cells.

Here, we have introduced the principle and implementation of FRET–FLIM technology and then focused on its applications in the biological field relative to four primary aspects: the internal mechanism of cellular action, causes of diseases, evaluation of drug treatment effects, and biosensors. This paper provides common means of information collection and data processing. The specific information is shown in Tables 1 and 2.

| FRET–FLIM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Research content | FRET pairs | Signal acquisition | Analytical method |

| DNA replication, repair29 | GFP/mCherry | Time domain method | Curve Fitting |

| Actin regulation34 | |||

| Ion channel of cell30 | EGFP/DsRed | Time domain method | Curve Fitting |

| Membrane transport31,32 | mCitrine/mCherry; GFP/mCherry | Time domain method | Curve Fitting |

| Interaction between Proteins33,43 | GFP/mCherry; CFP/YFP | Time domain method | Curve Fitting; Phasor Plot |

| Interaction between Transcription factors44,45 | GFP/YFP; SYFP2/mRFP | Time domain method | Phasor Plot |

| Interaction between Nucleic acid and protein40 | GFP/sytox-orange | Time domain method | Curve Fitting |

| Protein homology41 | GFP/mCherry | — | Statistical Analysis |

| Dimerization of the plant42 | GFP/RFP | Time domain method | Curve Fitting; Statistical Analysis |

| Technology of FRET–FLIM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Research content | FRET pairs | Signal acquisition | Analytical method |

| Spontaneous anticancer of cells46 | CFP/YFP | Frequency domain method | Curve Fitting |

| Dimerization of tumor cells47 | EGFP/HER2 | Time domain method | Curve Fitting |

| Viral infection49 | EGFP/mRFP | Time domain method | — |

| Pathology48,50 | mCitrine/mCherry | Time domain method | Curve Fitting |

2. FRET–FLIM Principle, Detection Method and Data Processing

2.1. FRET–FLIM principle

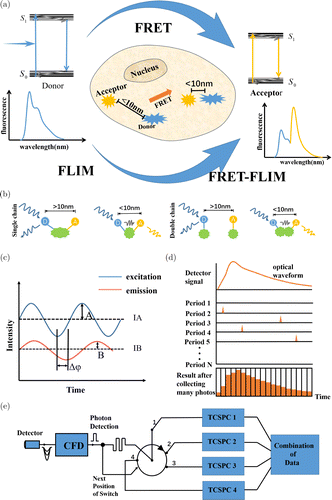

As indicated in Fig. 1(a), the electrons of a fluorescent molecule absorb energy, transitioning from the ground state to a high energy level of the excited state. After vibrational relaxation, the molecule falls to a low energy level of the excited state. These electrons then return to the ground state from the excited state while releasing photons that generate fluorescence. When FRET occurs, energy is transferred from the donor to the acceptor molecule. Then, the fluorescence of the donor becomes gradually weakened, and the acceptor fluorescent. The fluorescence lifetime of the sample gradually changes with the occurrence of FRET. As indicated in Fig. 1(b), FRET pairs can link in either a single-stranded or double-stranded form. In the single-stranded form, the FRET pairs link the same molecule, and FRET occurs when changes in the molecular structure alter the distance between the donor and acceptor molecules. In the double-stranded form, two independent targets are labeled with different fluorescent molecules, and FRET occurs when the two objects interact and the distance between the fluorescent molecules is reduced sufficiently.13,14,15,16,17,18

Fig. 1. FRET–FLIM effect generation principle, common structure and detection method. (a) FRET–FLIM generation schematic diagram; (b) FRET pairs’ structure in FRET–FLIM technology; (c) Frequency domain principle diagram; (d) TCSPC schematic diagram; and (e) Fast-TCSPC circuit diagram.

2.2. Detection method

Similar to the simple FLIM information acquisition technology, both the frequency and time-domain methods can be used for FRET–FLIM. The frequency-domain method uses a continuous light source with sinusoidal (Cosine) modulation to excite the sample. This method obtains fluorescence lifetime information from the delayed phase and the decreasing modulation amplitude of light. In contrast, the time-domain method uses highly repetitive pulsed laser excitation. The fluorescence lifetime information is obtained from the attenuation curve of the sample’s fluorescence intensity. The frequency and time domains can be converted using Fourier transform; therefore, in principle, both the frequency- and time-domain methods yield the same information.

In the frequency-domain method, a high-frequency (typically 10–100MHz) laser with sinusoidal (Cosine) modulation or a xenon lamp is used as the light source to excite the sample. Fluorescence is then emitted at the same frequency as the excitation source but with a phase lag and reduced modulation signal. A charge-coupled device or photomultiplier tube (PMT) with the same frequency modulation then is used as a detector to receive and demodulate the fluorescence signal, and the fluorescence lifetime information of the sample is obtained based on the phase difference and modulation coefficient,19 as indicated in Fig. 1(c).

Using Widefield frequency-domain fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FD-FLIM), Chen et al.20 tracked the temperature change of living cells via the fluorescence lifetime of Rhodamine B at different frequencies. Wu et al.21 construct a widefield frequency domain fluorescence imaging microscopy (FD-FLIM) system to accurately measure oxygen gradient profiles in a microfluidic device.

The time-domain method uses an ultrashort pulse laser to excite the sample. This method measures the fluorescence intensity attenuation after the sample is excited. As the probability of detecting a photon emitted within a certain time period ‘t’ and the fluorescence intensity is proportional to time, it is possible to measure the fluorescence lifetime by acquiring the fluorescence intensity attenuation information.

The principle of Time correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) is presented in Fig. 1(d); a high-sensitivity PMT, an avalanche photodiode (APD), or a microchannel plate detector (MCP) has been used as the detector. Each pulse laser excitation is considered a single cycle. Only one fluorescence emission photon can be collected in a single cycle. The time at which the photon appears is recorded. After the accumulation of photons in different cycles, the distribution frequency curve (or the fluorescence lifetime curve) is constructed. Long acquisition time is the most significant drawback of TCSPC. Becker developed a fast-acquisition fluorescence lifetime microscopy system, as shown in Fig. 1(e). The instrument response function has a width of less than 7ps and a time channel width as low as 820fs with nearly no stacking effect. TCSPC has a high time resolution, sensitivity, and efficiency. It can realize multidimensional detection and obtain a better signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the fluorescence lifetime.22,23

2.3. Data processing

In FRET–FLIM technology, it is important to get more information from the data. Currently, curve fitting and phasor plot are most commonly used for this purpose.24

In FRET–FLIM-acquired images measured using TCSPC, each pixel point contains position information and fluorescence decay data. The fluorescence decay curve is typically fitted by exponential model to estimate its corresponding fluorescence lifetime. This method is performed to optimize the goodness-of-fit by changing the values of the model parameters. The equation is given as follows :

Here, I(t) is the fluorescence intensity at time t; τn,αn is the fluorescence lifetime and contribution of each component, and C represents other effects (e.g., background noise, indoor light, and scattering effect). The contribution of each component to the total fluorescence lifetime is estimated over multiple iterations.

When using exponential fit to process image acquired in using FRET–FLIM technology, it is initially necessary to measure the fluorescence lifetime information of the donor fluorescent molecule. With the occurrence of FRET, various data, such as the fluorescence lifetime of sample and FRET’s efficiency, can be obtained via calculations.

Curve fitting requires appropriate number of exponential components, then fitting data in the given sample. More photons and a higher SNR is needed to accurately assume the exponential component; however, this may result in false fluorescence lifetime due to incorporation of nonsample components and system background noise. For FRET effect, multi-exponential fitting has no advantage in demonstrating changes of fluorescence lifetime.

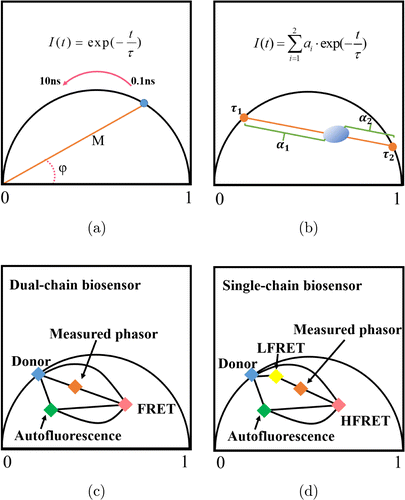

Phasor plot’s principle is shown in Fig. 2. In the phasor diagram, the extent and shape of FRET trajectory depends on the contribution of the background fluorescence. Mapping FRET–FLIM data measured to a semicircle, the fluorescence lifetime change of the sample can be more intuitively observed. Semicircle above the X-axis of radius 1 is called the unit circle. From the point (2, 0), the fluorescence lifetime value at the corresponding point gradually increases as the unit circle rotates counterclockwise. The points of single component sample are all located on the unit circle. The points of bi-component sample are located in the unit circle and distributed in a straight line. The position of data in the phase diagram can be determined using the following equation :

Fig. 2. Schematic diagram of phasor method. (a) Mono-exponential decay simulation; (b) bi-exponential decay simulation; (c) double-stranded FRET–FLIM phasor diagram under background influence; and (d) single-chain FRET–FLIM phasor diagram under background influence.

Here, Re and Im are the real and imaginary parts of the Fourier transform, respectively; I is the fluorescence intensity, and m and n are the indices of the rows and columns of the fluorescence image, respectively.25

Phasor analysis does not rely on input parameters and iterative process, has minimal constraints to provide higher accuracy; this makes the phasor method a reliable analytical method. Furthermore, the phasor method can be used to quickly estimate whether FRET occurs. In addition, it can reflect the dynamic fluorescence lifetime changes of both the donor and acceptor molecules. However, this method is difficult to quantify the fluorescence lifetime of each component in the sample.26,27,28

3. Application and Development of FRET–FILM Technology

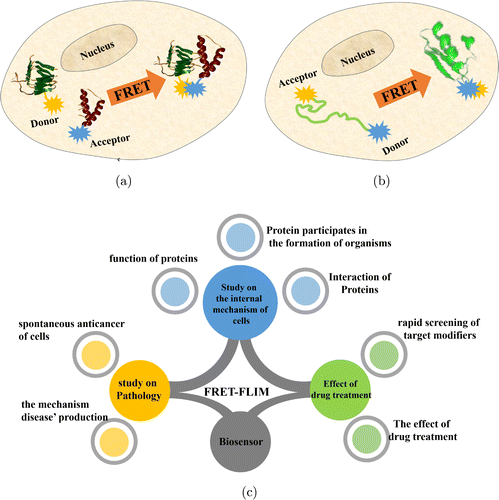

The intracellular applications of FRET–FLIM technology are illustrated in Figs. 3(a) and 3(b), which describe the principles used to detect protein–protein interactions and changes in protein structure. Figure 3(c) summarizes the common modern applications of FRET–FLIM technology in the biological field.

Fig. 3. Intracellular detection principle and application of FRET–FLIM technology. (a) Detect the interaction between proteins; (b) Detect the change of protein structure; and (c) Applications of FRET–FLIM technology.

3.1. Internal mechanism of cells

FRET–FLIM technology can analyze the physical and chemical change in intracellular substances, including protein interaction, apoptosis, and gene detection, as shown in Table 1.

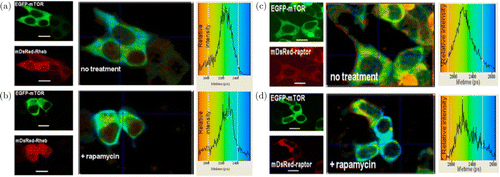

Trembecka-Lucas29 used FRET–FLIM technology to verify the interaction between HP1 and PCNA in DNA replication regions in living cells. Using FRET–FLIM technology, Yadav et al.30 demonstrated that mTOR directly interacts with Rheb or raptor. As shown in Fig. 4, Rheb can accurately locate the cytoplasm of mammalian cells.

Fig. 4. (a,b) FRET–FLIM image of EGFP-mTOR and mDsRed-Rheb; (c,d) FRET–FLIM image of EGFP-mTOR and mDsRed-raptor.30

Soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein attachment protein acceptor (SNARE) proteins are key for membrane trafficking; however, studying the precise functions of SNARE proteins is technically challenge. Verboogen31 fused the C-terminus of a SNARE protein with a fluorescent protein. By fitting the fluorescence lifetime histograms by a multicomponent decay model, FRET–FLIM technology allows (semi-)quantitative estimation of the formation rate of SNARE at different vesicles. This protocol can be applied to visualize SNARE complex formation at the plasma membrane and endosomal compartments in mammalian cell lines or primary immune cells. Using FRET–FLIM technology, Boal32 demonstrated that the point mutation e93v can reduce the direct interaction between cysteine-string protein (Csp) and calcium sensor synaptotagmin9(Syt9). Kim Dore33 used FRET–FLIM technology to detect the interaction between the protein N-methyl-D-aspartate and postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) in cultured rat hippocampal neurons during epithelial remodeling. In this way, Yamada34 co-localized the endogenous aptamers amphiphysin 1 and neural Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome expressed in the peripheral folds in Sertoli cells and confirmed the association between the two proteins in vivo.

FRET–FLIM technology can also be used to study the mechanism of action of specific proteins in plant cells, protein interactions in plant endometrial systems, protein oligomer formation, and biomacromolecular interactions.35,36,37,38,39

Camborde40 labeled the target protein with green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a donor and treated the leaves with the nucleic acid dye SYTOX Orange as an acceptor. Detection by FRET–FLIM technology demonstrated a significant reduction in the GFP lifetime, thereby indicating that the GFP-tagged protein interacted with the SYTOX Orange-stained nucleic acid. Using FRET–FLIM technology, Veerabagu41 demonstrated that the modified state of aspartic acid (D70) resulted in homology of the response modifier (ARR18). This experiment provides a new perspective on how B-type response regulators bind to their homologous DNA sequences. Dierk42 labeled heterozygous fusion proteins with GFP/RFP and verified the formation of parallel dimers in plants using FRET–FLIM technology.

WRKY18 is able to bind directly to different W-boxes in the WRKY53 promoter region and to repress expression of the WRKY53 promoter-driven reporter gene in a transient transformation system using Arabidopsis protoplasts. Potschin43 used FRET–FLIM technology to detect an interaction between WRKY53 and WRKY18 proteins in transiently transformed tobacco epidermal cells.

Long et al.44 used FRET–FLIM technology combined with the phasor plot method to reveal the spatial division of protein interactions associated with cell fate specifications. Their results demonstrated that three fully functional fluorescently labeled cell-fate regulators establish cell type-specific interactions at endogenous expression levels and form more advanced complexes. They further tested the interaction between SHORT-ROOT and SCARECROW, indicating that the spatial distribution of the interaction between two transcription factors can be highly regulated in repetitive and structurally similar organs, thereby providing new information about the dynamic redistribution of protein complex configurations at different developmental stages.45

3.2. Disease causes

We can research the role of proteins involved in the disease production process by using FRET–FLIM technology. In the course of disease treatment, drug enters the human body via injection or oral administration. After drug reaches the human body, it uses biomolecules as medium to achieve therapeutic effects by inhibiting or promoting a certain protein. FRET pairs are used to target protein, then the position, conformation, and other information of proteins are obtained by observing the experimental results. Thus, a further understanding of the mechanism and effect of the drug therapy can be achieved. The applications of FRET–FLIM technology in pathological research have been presented in Table 2.

Cells reduce gap junction coupling during tumor metastasis, Majoul et al.46 speculated that this might be so to prevent malignant transformation. Using FRET–FLIM technology, they found that Arf6 directs Cx43 to play a role in developing and migrating cells and Cx43 expression inhibits the growth of glioblastoma cells in humans. Waterhouse et al.47 used primary antibodies from different species together with Alexa488- and Alexa546-conjugated secondary antibodies to validate EGFR in the following three cell lines: EGFR-positive cancer cell line A431, HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines BT474 and SKBR3. HER2 dimerization assay experiments have shown that this method can be applied to tissue microarrays, thereby allowed in situ assessment of the dimerization status of tumor cells and the determination of predicted value of tumor samples measured in the clinical environment.

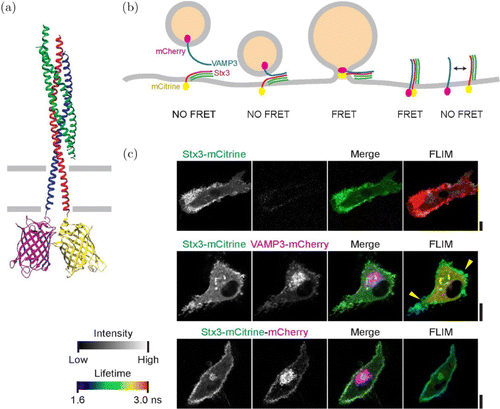

As shown in Fig. 5, Verboogen48 used FRET–FLIM technology to describe the transport process of the release of the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 from human blood-derived dendritic cells. This experiment demonstrated the applicability of FRET–FLIM technology to visualize SNARE complexes in living cells at a subcellular spatial resolution.

Fig. 5. SNARE complex formation by FRET–FLIM. (a) Model of the neuronal SNAREs; (b) Scheme of membrane fusion resulting in FRET; (c) Representative confocal microscopy (left) and FLIM (right) images of dendritic cells expressing Stx3-mCitrine (green in merge; upper panels), Stx3-mCitrine with VAMP3-mCherry (magenta; middle panels), or Stx3 conjugated to both mCitrine and mCherry (Stx3-mCitrine-mCherry; lower panels).48

Beet necrotic yellow vein virus RNA-1 encodes a nonstructural p237 polyprotein processed as two proteins (p150 and p66) by cis-acting protease activity. Pakdel and Mounier49 experimentally demonstrated the interaction between functional domains of the p150 and p66 proteins and the addressing of benyvirus replicase to the endoplasmic reticulum. They simultaneously used FRET–FLIM technology to indicate the presence of multimeric complexes near the cell membrane network.

3.3. Evaluation of drug treatment effects

Cancerous cells are generally produced due to errors in gene expression, and metastasis and infection are achieved by biological macromolecules. Highly targeted drugs have become a hot topic relative to the treatment of cancer. Detecting the therapeutic effect of drugs at the molecular level is a significant challenge. FRET–FLIM technology can image deep tissues of cancer, thereby permitting the use of rapid target-modification and high-level drug screening, FRET–FLIM technology is expected to become an important means of detecting the therapeutic effects of drugs on targeted detect proteins in tumor cells or tissue specimens.50

Coban51 used FRET–FLIM technology two-color single-molecule tracking to study the effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and phosphatase-based manipulation of EGFR phosphorylation on live cells. The results indicated that a modest drug-induced increase in the fraction/stability of EGFR homodimer may have significant biological impact on the proliferation potential of tumor cells.

3.4. Application of FRET–FLIM in biosensors

Monitoring different signaling enzymes in a single assay using multiplex biosensor provides a multidimensional workspace to elucidate biological process, signal pathway crosstalk, and determine precise sequence of events at the single living-cell level. Demeautis52 proposed a validated method for multi-parametric kinase biosensor in living cells using FRET–FLIM technology. Using single excitation wavelength dual-color FLIM technology and FRET biosensor, they could detect donor molecules as to measure PKA and ERK1&2 kinase activities in the same cellular location.

4. Summary and Outlook of FRET–FLIM Technology

Nowadays, FRET–FLIM technology is mainly used to solve various biological problems that need to meet the requirement of high precision and multiple dimensions. Although biochemical tests such as co-immunoprecipitation can also be used to study protein interactions, this method lacks spatial information. The resolution of the Confocal laser scanning microscope can reach 250nm. FRET–FLIM technology breaks through this limit, achieving a high resolution of intracellular interactions of the molecular scale in cells. It has little dependence on the fluorescence intensity, on comma and has a high sensitivity to detect the interaction between low expression proteins under natural conditions. This technology is noninvasive thus dose not influence cell morphology.

FRET–FLIM technology is mainly divided into three parts: fluorescent labels, detection means and data analysis. Fluorescent molecules as a marker should have good optical properties such as higher quantum yield, light stability and biological affinity. Nowadays, the choice of labels is no longer limited to fluorescent dyes and probes. Researchers use new materials to accomplish the aim, such as graphene quantum dots and gold nanorods. To achieve biomicroscopic imaging and detection in vivo, FRET–FLIM technology should have the advantages of short measurement time, high precision, be simple to operate and low in cost. Among all the methods, TCSPC has the highest time resolution, but its acquisition speed is slow. The frequency-domain method has low requirements on equipment, low cost, and high data processing speed, but its performance index is not as good as the time-domain method. Using algorithms can get lots of information from the acquired data.

The potential value of FRET–FLIM technology in the biomedical field has not been fully explored, and the practical application of this technology still faces challenges. First, the FRET–FLIM system is relatively complex and has high requirement for the light source, expensive detectors, its large hardware system limits the flexibility of clinical diagnostic techniques. FRET pairs that have high light stability and biological affinity are also a key for this method of transforming to the clinical. Second, it usually takes a few seconds to acquire a high-quality image, and several tens of minutes are needed to obtain a certain depth of three-dimensional image. Increasing the quantum yield of fluorescent particles can improve this problem to some extent, and the breakthrough in imaging speed depends on the further improvement of detection method. New algorithms are needed to solve multi-component problems in biomedical samples. Third, high biological tissue penetration and super-resolution are also the development orientation of FRET–FLIM technology. It can combine with other technologies which can provide deep tissue information such as photoacoustic imaging. The development of new multi-modal imaging systems is also expected to expand diagnosis capabilities of FRET–FLIM technology.

Acknowledgments

This work has been partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61722508/61525503/61620106016/81727804). The National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0700402), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation Innovation Team (2014A030312008), and Shenzhen Basic Research Project (JCYJ20150930104948169/JCYJ20160328144746940/GJHZ20160226202139185/JCYJ20170412105003520)