Transformational change in the field of diffuse optics: From going bananas to going nuts

Abstract

The concept of region of sensitivity is central to the field of diffuse optics and is closely related to the Jacobian matrix used to solve the inverse problem in imaging. It is well known that, in diffuse reflectance, the region of sensitivity associated with a given source–detector pair is shaped as a banana, and features maximal sensitivity to the portions of the sample that are closest to the source and the detector. We have recently introduced a dual-slope (DS) method based on a special arrangement of two sources and two detectors, which results in deeper and more localized regions of sensitivity, resembling the shapes of different kinds of nuts. Here, we report the regions of sensitivity associated with a variety of source–detector arrangements for DS measurements of intensity and phase with frequency-domain spectroscopy (modulation frequency: 140MHz) in a medium with absorption and reduced scattering coefficients of 0.1 and 12 cm−1, respectively. The main result is that the depth of maximum sensitivity, considering only cases that use source-detector separations of 25 and 35 mm, progressively increases as we consider single-distance intensity (2.0mm), DS intensity (4.6mm), single-distance phase (7.5mm), and DS phase (10.9mm). These results indicate the importance of DS measurements, and even more so of phase measurements, when it is desirable to selectively probe deeper portions of a sample with diffuse optics. This is certainly the case in non-invasive optical studies of brain, muscle, and breast tissue, which are located underneath the superficial tissue at variable depths.

1. Introduction

The field of diffuse optics, and more specifically its applications to noninvasive measurements of biological tissue, relies on the large optical penetration depth (of the order of centimeters) of near-infrared light into tissue. This property allows for noninvasive sensing of deep tissues, albeit with an intrinsically low spatial resolution of the order of 1cm. Target tissues include the human brain,1 skeletal muscle,2 and lobules and ducts in the human breast,3 which must be interrogated through superficial tissue layers: scalp and skull for the brain, skin and subcutaneous lipid layer for muscle, skin and fatty tissue for the breast. Any diffuse optical study of tissue needs to consider potential confounds from superficial tissue that may obscure contributions to the optical signal from the target tissue. While this is true for any noninvasive application of diffuse optics, the severity of the signal contamination from superficial tissue can vary significantly depending on the target tissue, anatomical and physiological features, optical signal measured, properties of the optical probe, reflectance versus transmittance mode, etc.

As one may expect, given the importance of this problem, significant efforts have been devoted to separating the contributions to the measured optical signals that originate from superficial tissue and from the deeper target tissue. This is especially true in the case of noninvasive optical measurements of the brain. A common approach is based on direct measurements of the superficial tissue contributions using “short” source–detector separations (5–10mm), and methods to remove these contributions from the optical signals collected at “large” source–detector separations (25–35mm), which are sensitive to both brain and superficial extracerebral tissue. While conceptually straightforward, this approach is not of trivial application because it needs to either rely on a lack of correlation between extracerebral and cerebral tissue contributions, or quantify the extent to which the extracerebral tissue contributes to the signal recorded at large source–detector separation. Several approaches have been proposed to combine signals collected at short and long source–detector separations: a regression method based on a least square algorithm,4 adaptive filtering,5 state-space modeling,6 or independent component analysis.7 There is a further complication related to spatially inhomogeneous optical changes in the superficial tissue, which has been addressed by introducing two sets of short-distance source–detector pairs.8 Finally, one should consider that short source–detector separations, especially in the presence of hair, may lead to the collection of stray light, i.e., light that has not traveled through tissue but rather finds its way from the source to the detector via reflection or scattering externally to tissue. This is a further practical complication of methods based on the combination of short and long source–detector distances. More general solutions to this problem are afforded by layered reconstructions9,10 or full tomographic approaches,11 which aim to separately reconstruct the optical changes in superficial and deeper tissue from optical measurements obtained with an array of sources and detectors on the tissue surface.

In this paper, we consider a conceptually different approach to addressing the issue of potential confounds from superficial tissue. Rather than trying to characterize or measure the contributions from superficial tissue, we propose to suppress the sensitivity of the optical signals to them. The optical sensitivity of a signal collected with a source–detector pair in diffuse reflectance is represented by a banana-shaped region,12 the so-called “photon banana,” which narrows at the source and detector locations and broadens as it extends into deeper tissue regions. The optical sensitivity within this banana-shaped region is not spatially uniform and is maximal for superficial tissue that is close to the source and the detector. In line with the approach considered in this work, it was previously suggested to use either one source and multiple detectors or one detector and multiple sources to reduce the sensitivity to a superficial tissue layer by considering slopes13,14 (what we call here “single slopes,” as defined in Sec. 2.1) or by subtraction methods.15 Despite the effectiveness of these approaches in reducing the sensitivity to thin, uniform superficial layers, they still feature banana-shaped regions of sensitivity (albeit asymmetrical and bimodal) with maximal sensitivity close to the tissue surface for localized inhomogeneities.16,17,18 In this paper, we consider an extension of single-slope (SS) methods that significantly improves upon them in terms of depth sensitivity.

As an alternative to a single distance (SD) or a SS arrangement, we have recently proposed to use a special arrangement of two sources and two detectors to collect signals in a dual-slope (DS) approach that features a dramatically different region of sensitivity.16,17 Such region of sensitivity, rather than extending all the way to the surface, is confined to deeper tissue and resembles the shape of nuts rather than bananas (hence the title of this paper). The major outcome is that the region of maximal sensitivity is not at or close to the tissue surface (as in the case of the photon bananas), but is rather located deeper in the tissue. The depth of maximal sensitivity depends on the SD arrangement and is significantly greater for phase measurements (in frequency-domain diffuse optics) than for intensity measurements (in continuous-wave diffuse optics). Similar SD arrangements have also been considered to improve the depth sensitivity associated with statistical moments of the photon time-of-flight distribution measured in the time domain.18 Here, for the first time, we report the shape of the region of sensitivity for a variety of DS SD arrangements.

2. Methods

2.1. Source–detector arrangements for dual slopes of intensity and phase

The most basic approach to diffuse optical measurements, especially in reflectance mode, employs a single SD pair, which obviously features a single distance between source and detector. An extension to this approach relies on the measurement of slopes (or gradients) of optical signals versus source–detector distance. This method requires collecting data at multiple (at least two) source–detector distances, which are typically realized using either a single source and multiple detectors or a single detector and multiple sources. We refer to this method as a SS method. A third approach, based on a concept originally introduced by Hueber et al.19 and recently revisited and further developed by us16,17 relies on averaging two paired slopes obtained with a special arrangement of a minimum of two sources and two detectors. We refer to this method as a DS method. Here, we limit ourselves to the case of exactly two sources and two detectors, which is most practical and achieves the key objectives of the DS method. The requirements for an arrangement of two sources (S1, S2) and two detectors (D1, D2) that is suitable for DS measurements are as follows:

| (i) | The distances between each source and the two detectors must be different, so that the two sets (S1, D1, D2) and (S2, D1, D2) realize two SS measurements, which we label SS1 and SS2; | ||||

| (ii) | The source–detector distance difference in SS1 and SS2, which we identify with ΔρSS1 and ΔρSS2, respectively, must be the same (ΔρSS1=ΔρSS2); | ||||

| (iii) | If the distance between S1 and D1 is the shorter distance for SS1, then the distance between S2 and D1 must be the longer distance for SS2 (and vice versa). This condition and the one above (condition ii), are required for cancellation of unknown factors related to source emission and detector sensitivity properties, as well as unknown or variable efficiency of optical coupling between the optical probe and tissue; | ||||

| (iv) | The common value ΔρSS1=ΔρSS2 must be limited to within a range; if Δρ is too small, the difference in the optical signals at the two distances may not exceed the measurement noise, whereas if Δρ is too large, the difference in the optical signals at the two distances may exceed the available dynamic range. In this paper, we consider a range of values for Δρ of 10–20mm; | ||||

| (v) | The shorter source–detector distance in SS1 and SS2 must be greater than a minimum value that guarantees a suitable optical penetration beyond the superficial tissue layer. Such minimum value depends on the specific application. In this paper, we consider a ρmin of 20mm; | ||||

| (vi) | The longer source–detector distance in SS1 and SS2 must be less than a maximum value that fulfils condition (iv) and that guarantees a suitable signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the optical signal. In this paper, we consider a ρmax of 40mm. | ||||

One may see points (i)–(iii) above as strict requirements for the theoretical applicability of the dual slope approach, whereas points (iv)–(vi) are considerations for its practical applicability under given experimental conditions.

One can appreciate that there are many source–detector arrangements that satisfy the above requirements. In this paper, we report a variety of such arrangements, and for each of them we report the associated regions of sensitivity, defined according to the sensitivity functions that are introduced next.

2.2. Sensitivity functions

The sensitivity of a diffuse optical signal to a given tissue volume is related to the photon hitting density, or partial optical pathlength, within that volume.20 One can express the sensitivity of a particular optical signal (intensity, phase, moments of the time-of-flight distribution, etc.) to a local change in a given optical parameter in terms of photon-measurement density functions.21 It is the latter concept that is relevant here, and may be expressed by the following sensitivity (SENS) of an optical signal (𝒫) to a point-like absorption perturbation at location r (δμa,r)21,22 :

In this paper, we adopt a related definition of sensitivity (S), which is a dimensionless ratio where the numerator is the apparent absorption change (Δμa(𝒫,r)) obtained from signal 𝒫, and the denominator is the actual value of the absorption perturbation, δμa,r :

In the case of two-source/two-detector arrangements suitable for DS intensity and phase measurements, which we indicate with DSI and DSϕ, respectively, the expressions of Eqs. (3) and (4) become16 :

In light of Eqs. (3), (4), (5), and (6), one can appreciate that the sensitivity definition of Eq. (2) simply represents a combination of partial mean pathlengths within the absorption perturbation and total mean pathlengths (or generalized pathlengths in the case of phase or slope measurements) associated with the optical signal of interest.

2.3. Diffusion theory for a semi-infinite medium containing an absorption inhomogeneity

The regions of sensitivity for intensity and phase in single-distance (SD) and DS configurations were obtained using diffusion theory in a semi-infinite geometry. All light sources and optical detectors were placed at the interface between the scattering medium (tissue) and the outside nonscattering medium (air), on the x-y plane at z=0 (with the scattering medium occupying the half-space z>0). We have considered an intensity modulation frequency of 140MHz. We introduced an effective point-source located inside the medium, underneath the actual light source, at a depth z=1∕μ′s and considered extrapolated boundary conditions, with the extrapolated boundary at z=−2A∕(3μ′s), where A is a reflection factor that depends on the refractive index mismatch at the interface.26 In our case, for a tissue–air interface with a refractive index ratio of ∼1.4, A=2.95. We considered a medium with an absorption coefficient μa=0.1cm−1 and a reduced scattering coefficient μ′s=12cm−1. Consequently, the effective sources were at a depth of 0.8mm inside the medium, and the extrapolated boundary was 1.6mm outside the medium.

The optical signals in the presence of a localized absorption inhomogeneity were computed with first-order perturbation theory. The absorption perturbation was set to have an absorption coefficient 30% greater than the background (Δμa=0.03cm−1), and a size of 10 mm×10mm×2mm along x, y, and z, respectively. The rationale for this choice is provided in Sec. 4. As this absorption perturbation was scanned within the medium, the sensitivity obtained from Eqs. (3), (4), (7), and (8) was assigned to its central location to map the region of sensitivity.

To take into account the different noise level of intensity and phase measurements with single-distance and DS methods, we set a threshold for the sensitivity values at a SNR of 1. In other words, we gray out sensitivity values that are equal or less than the noise level. To estimate such noise level, we have considered an intensity noise of 0.4% and a phase noise of 0.06∘, which are propagated to yield noise levels for various sensitivities that are considered.

3. Results

The 13 figures in this paper illustrate the regions of sensitivity for a variety of source–detector configurations. Figures 1 and 2 report single-distance (SD) cases, whereas Figs. 3–13 report DS cases. While there are many different ways to arrange two sources and two detectors to realize DS measurements, in this paper, we report a set of representative cases that embody a variety of cases, including linear, square, rectangular, rhomboid, and trapezoid arrangements. The objective of this paper is to describe the regions of sensitivity of the various arrangements, with the two-fold purpose of (1) illustrating the DS approach, and (2) providing indications of different spatial sensitivity features that may be achieved. These different features can inform the selection of the most suitable arrangement(s) for specific applications that may target either point measurements or imaging.

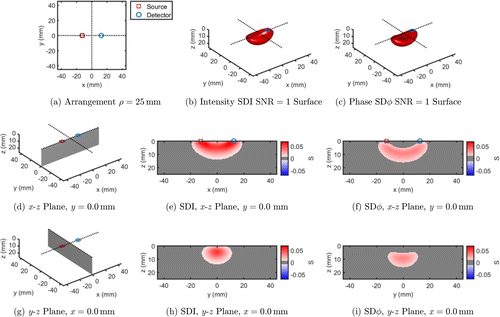

Fig. 1. Single-distance (SD) case: ρ=25mm. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0. 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity; SDϕ: single-distance phase.

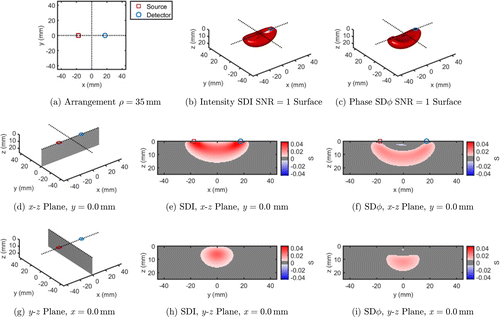

Fig. 2. SD case: ρ=35mm. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0.3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity; SDϕ: single-distance phase.

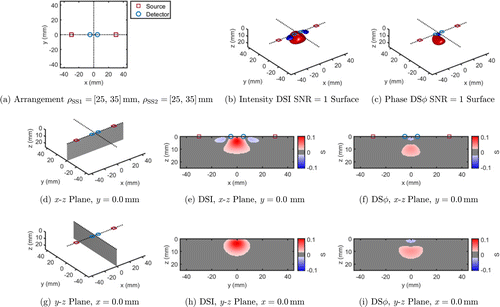

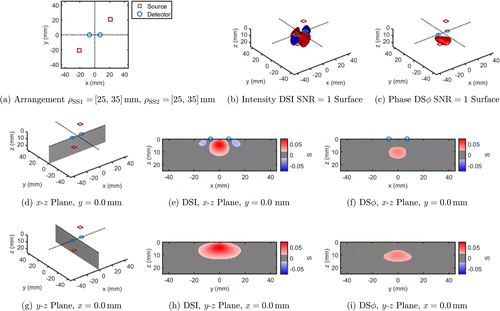

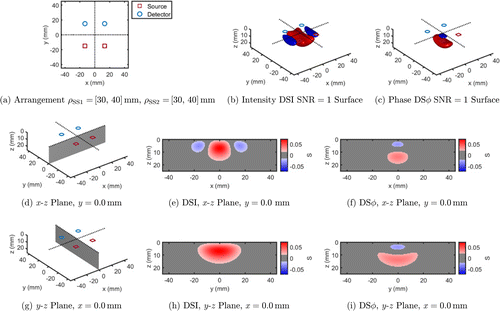

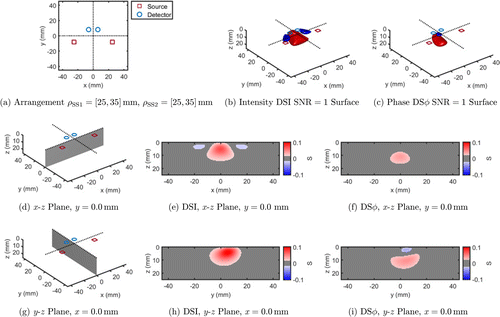

Fig. 3. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 25, 35mm (ρSS1) and 25, 35mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Linear: LIN). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity; SDϕ: single-distance phase.

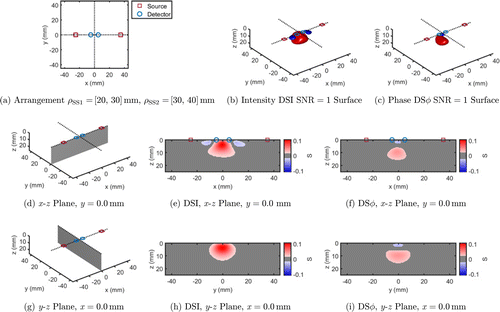

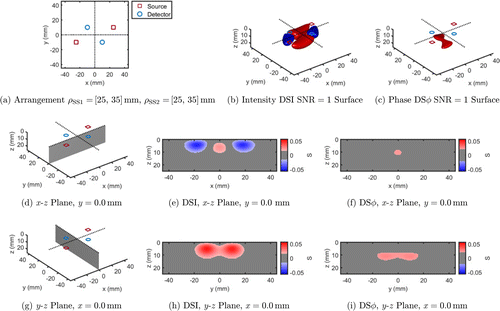

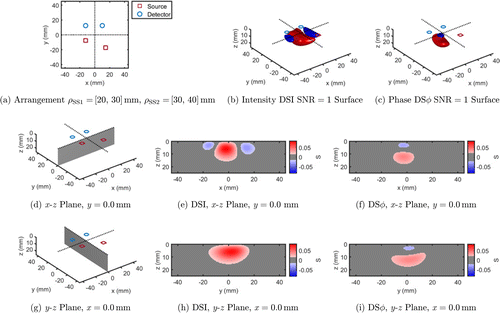

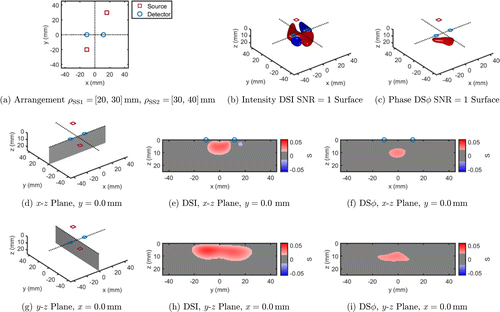

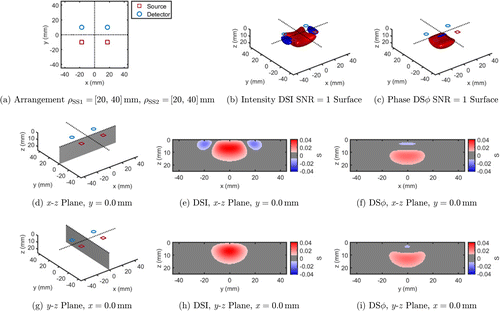

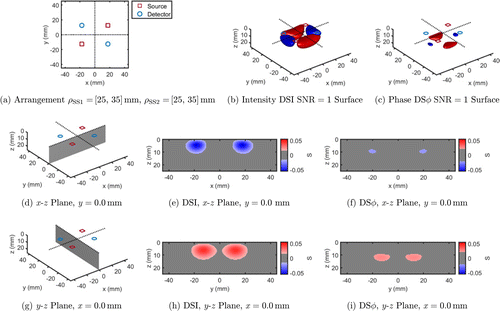

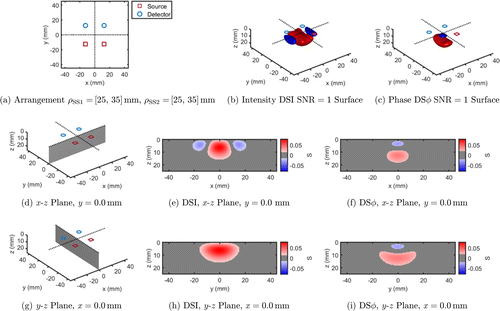

In all figures, panel (a) reports the arrangement of sources (red squares) and detectors (blue circles) on the x-y plane (at z=0), with an indication of the relevant source–detector distances (ρ in the single-distance case of Figs. 1 and 2; ρSS1 and ρSS2 in the DS case of Figs. 3–13). Panels (b) and (c) report a 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for intensity and phase, respectively, with surfaces defined by a SNR of 1, and color-coded signs of sensitivity (red: positive; blue: negative). Panel (d) shows the x-z plane (at y=0) for which the cross-section of the regions of sensitivity of intensity and phase are shown in panels (e) and (f), respectively. Finally, panel (g) shows the y-z plane (at x=0) for which the cross-section of the regions of sensitivity of intensity and phase are shown in panels (h) and (i), respectively.

Figures 1 and 2 show single-distance (SD) cases at ρ=25mm (Fig. 1) and ρ=35mm (Fig. 2), where one can appreciate the banana shaped region of sensitivity for both intensity and phase in the 3D rendition ((b) and (d)) and in the x-z plane ((e) and (f)). A comparison of Figs. 1 and 2 shows the expected deepening of the overall regions of sensitivity with increasing source–detector distance. A comparison of panels (e) and (f), and panels (h) and (i) in Figs. 1 and 2 shows the deeper sensitivity of phase versus intensity data. This result is consistent with the previous reports of regions of sensitivity in the frequency domain,27 a deeper sensitivity of the first moment (essentially the phase), and even more so of the second moment (variance), versus the zeroth moment (intensity) of the photon time-of-flight distribution measured in the time domain,28 and a stronger sensitivity to brain tissue of phase versus intensity measurements in noninvasive brain studies.29,30

Figures 3–13 show the DS regions of sensitivity for intensity (center panels) and phase (right panels) for a variety of source–detector configurations that are suitable for DS measurements. The source–detector distances are the same (25 and 35 mm) or comparable (20–40mm) to the single-distances of Figs. 1 and 2, so that a comparison of the depth of sensitivity is meaningful across all figures. Some of the DS arrangements are symmetrical (Figs. 3, 5, 6, 9, 10–13) and some are asymmetrical (Figs. 4, 7 and 8). We refer to the reported configurations as linear (LIN) (Figs. 3 and 4), rhomboid (RHO) (Figs. 5 and 6), quadrilateral (QDL) (Fig. 7), irregular (IRR) (Fig. 8), rectangular (RCT) (Figs. 9–11), square (SQR) (Fig. 12), trapezoid (TPZ) (Fig. 13).

Fig. 4. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 20, 30mm (ρSS1) and 30, 40mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Linear: LIN). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 5. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 25, 35mm (ρSS1) and 25, 35mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Rhomboid: RHO). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 6. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 25, 35mm (ρSS1) and 25, 35mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Rhomboid: RHO). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 7. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 20, 30mm (ρSS1) and 30, 40mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Quadrilateral: QDL). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 8. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 20, 30mm (ρSS1) and 30, 40mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Irregular: IRR). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 9. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 30, 40mm (ρSS1) and 30, 40mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z = 0 (Rectangle: RCT). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x = 0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 10. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 20, 40mm (ρSS1) and 20, 40mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Rectangle: RCT). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 11. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 25, 35mm (ρSS1) and 25, 35mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Rectangle: RCT). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y = 0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 12. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 25, 35mm (ρSS1) and 25, 35mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Square: SQR). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

Fig. 13. DS case based on two single slopes (SS1 and SS2) that feature source–detector distance of 25, 35mm (ρSS1) and 25, 35mm (ρSS2), respectively. (a) Source–detector arrangement in the x-y plane at z=0 (Trapezoid: TPZ). 3D rendition of the regions of sensitivity for (b) intensity and (c) phase. (d) Longitudinal x-z plane at y=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (e) intensity and (f) phase. (g) Transverse y-z plane at x=0 (shaded), and cross-sections over this plane of the regions of sensitivity for (h) intensity and (i) phase. All regions of sensitivity are bounded by the surface or line at a SNR of 1. SDI: single-distance intensity and SDϕ: single-distance phase.

The cross-sections in the x-z plane of the regions of sensitivity in Figs. 3–13 resemble, rather than the bananas of Figs. 1 and 2, different kinds of nuts (hazelnuts, chestnuts, cashew nuts, etc.), and one can even see a peanut in the y-z cross-sections of Figs. 6(h) and 6(i). Most importantly, the maximum value of the region of sensitivity occurs deeper in the tissue for DS than for single-distance and is always deeper for the phase than for the intensity. In Table 1, we report the value and coordinates of the maximal sensitivity of intensity and phase for all source–detector arrangements considered in Figs. 1–13. From Table 1, one may appreciate the trade-off between depth of sensitivity and level of sensitivity for intensity versus phase, and for single-distance versus dual slope. In particular, considering only cases that use source–detector separations of 25 and 35mm for a more meaningful comparison, the depth of maximum sensitivity progressively increases as we consider single-distance intensity (2.0mm), DS intensity (4.6mm), single-distance phase (7.5mm), and DS phase (10.9mm). Correspondingly, the value of maximum sensitivity for these cases is: single-distance intensity (0.058), DS intensity (0.077), single-distance phase (0.027), and DS phase (0.036).

| Intensity | Phase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Shape-Figure | Distances (mm) | Maximum sensitivity | x (mm) | y (mm) | z (mm) | Maximum sensitivity | x (mm) | y (mm) | z (mm) |

| SD | Fig. 1 | 25 | 0.069 | ±9.0 | 0 | 2.0 | 0.033 | ±7.5 | 0 | 7.5 |

| Fig. 2 | 35 | 0.046 | ±14.0 | 0 | 2.0 | 0.021 | ±14.5 | 0 | 7.5 | |

| DS | LIN - Fig. 3 | 25,35 | 0.105 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 0.043 | 0 | 0 | 9.5 |

| LIN - Fig. 4 | 20,30,40 | 0.107 | −0.5 | 0 | 3.5 | 0.044 | −1.0 | 0 | 9.5 | |

| RHO - Fig. 5 | 25,35 | 0.075 | 0 | 0 | 4.0 | 0.038 | 0 | 0 | 10.0 | |

| RHO - Fig. 6 | 25,35 | 0.053 | ±3.0 | ±10.0 | 4.5 | 0.027 | ±1.0 | ±10.0 | 11.0 | |

| QDL - Fig. 7 | 20,30,40 | 0.084 | −2.0 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 0.041 | −2.5 | 2.0 | 12.0 | |

| IRR - Fig. 8 | 20,30,40 | 0.059 | 6.0 | −5.5 | 4.0 | 0.030 | 3.0 | −4.5 | 10.0 | |

| RCT - Fig. 9 | 30,40 | 0.073 | 0 | 0 | 7.0 | 0.037 | 0 | 0 | 13.5 | |

| RCT - Fig. 10 | 20,40 | 0.041 | 0 | 0 | 7.0 | 0.024 | 0 | 0 | 13.0 | |

| RCT - Fig. 11 | 25,35 | 0.048 | ±8.5 | ±13.0 | 5.0 | 0.026 | 0 | ±12.5 | 12.0 | |

| SQR - Fig. 12 | 25,35 | 0.079 | 0 | 0 | 6.5 | 0.040 | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | |

| TPZ - Fig. 13 | 25,35 | 0.102 | 0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 0.043 | 0 | 4.5 | 10.5 | |

It is important to point out that the sensitivity to deeper tissue (say, at a fixed depth of ∼10mm) is comparable (∼0.03 under the conditions considered in this work) for single distance and dual slope measurements. However, the contrast-to-noise ratio may be better for intensity measurements as they typically feature lower noise than phase measurements. In any case, DS data feature a sensitivity to deep tissue that is comparable to that of single-distance data, but without the confounding effects of a greater sensitivity to shallower tissue.

We also point out that a negative sensitivity to an absorption perturbation indicates a change in the measured signal that is in the opposite direction than expected from a homogenous absorption perturbation. Equations (5), (6), (9), and (10) specify that a uniform increase in absorption (Δμa>0) results in a decrease in single-distance intensity, single-distance phase, DS intensity (more negative slope), and DS phase (less positive slope) (i.e., ΔSDIDC<0, ΔSDϕ<0, ΔDSIDC<0, ΔDSϕ<0). By contrast, it can be possible that a superficial and localized absorption increase may result in a greater single-distance phase, dual-slope-intensity, and/or DS phase (but never in a greater single-distance intensity). Such signal increases in response to a localized increase in absorption are associated with a negative sensitivity.

4. Discussion

The regions of sensitivity reported in this paper show the dramatic difference between the sample volumes probed by single-distance and DS optical data. In particular, we point out how the banana-shaped sensitivity regions of the single-distance case (Figs. 1 and 2) extend to the most superficial tissue underneath the source and the detector, which contrasts with the nut-shaped sensitivity regions of the DS cases (Figs. 3–13) that are more localized within deeper tissue. It is important to comment on the representation for regions of sensitivity used in this paper. This representation is based on SNR considerations, so that, in all figures, the 3D renditions in panels (b) and (c) and the cross-sections of panels (e), (f), (h), and (i) are bounded by SNR=1. This requires a specification of the signal and the noise considered. For the signal, i.e., the optical perturbation caused by the absorption inhomogeneity, we have considered a rectangular region of size 10mm×10mm×2mm (x, y, z dimensions) that features an absorption coefficient 30% greater than the background. This choice is based on estimates of the lateral size (∼10mm) of focal hemodynamic changes in extracerebral and cerebral tissue, the approximate thickness of scalp and cerebral cortex (∼2mm), and the blood volume change associated with brain activation (∼30%).31 For the noise, we have considered values of 0.4% for the intensity and 0.06∘, which we obtained from phantom measurements using typical data acquisition parameters used for in vivo diffuse optical measurements. Of course, different optical inhomogeneities will result in different signals, and different instrumental configurations will result in different noise levels. However, the key fact illustrated in Figs. 1–13 is the relative level of sensitivity to deep versus shallow tissue for a given optical perturbation measured with intensity or phase using single-distance or DS methods.

Another important point related to the discussion of the previous paragraph is that the white areas in the 3D renditions and the grey areas in the cross-sections of the regions of sensitivity do not represent a zero sensitivity, but rather a sensitivity below the threshold of SNR=1. This means that a local perturbation may still be detected outside the depicted regions of sensitivity, provided it features a large enough optical contrast. In other words, even in the case of nut-shaped regions of sensitivity that only appear deep in the tissue (such as the one in Fig. 8(f)), it may still be the case that a high-contrast superficial perturbation results in the same signal as a low-contrast deep perturbation. Furthermore, it is possible that multiple low-contrast absorption perturbations, each associated with a SNR<1, may collectively result in a SNR>1. The quantitative description of sensitivity provided in Eq. (2), in conjunction with Eqs. (3), (4), (7), and (8), allows for the determination of the optical signal associated with perturbations of any size and absorption contrast (at least within the case of first-order perturbation theory considered here). It is also worth pointing out that both intensity and phase dual slopes feature negative sensitivities to localized superficial tissue. Even though these negative sensitivities are typically weaker than the deeper positive sensitivities and tend to be highly localized, they may nevertheless result in misleading results in the case of similarly localized superficial perturbations with a relatively high optical contrast. In fact, they may yield contributions to the apparent absorption changes that are opposite to the actual ones.

An evident result of Figs. 1–13, further quantified in Table 1, is the deeper sensitivity of phase data with respect to intensity data, regardless of the approach (single-distance or dual-slope). This result indicates that stand-alone phase data can play an important role in diffuse optics, beyond its more common use in combination with intensity data to quantify both absorption and scattering properties of tissue. Such a role is to improve the sensitivity to deeper tissue and enhance imaging applications of diffuse optics rather than performing absolute measurements of optical properties of turbid media and tissue.

Finally, we’d like to comment on the relevance of illustrating a large variety of source–detector arrangements for DS measurements. In fact, it is true that some arrangements, most notably the linear one of Fig. 3, may be optimal from a practical point of view, and for its minimal sensitivity to inaccuracies in the source–detector locations and to deformations of the probe when conforming to a curved tissue. However, there are at least two reasons for considering a variety of DS source–detector arrangements. The first reason is practical: spatial constraints, tissue curvature, or other limiting factors may prevent the use of specific source–detector arrangements, and it is important to have alternative options to consider. The second reason is more fundamental: imaging applications require the collection of data with multiple DS configurations that cover the entirety of the tissue to be imaged, ideally with overlapping regions of sensitivity. The family of DS configurations illustrated in Figs. 3–13, with additional variants achieved by further displacements of sources and/or detectors, gives a sense of the flexibility that one has for combining subsets of optodes in a source–detector grid for dual-slope-based imaging applications. This is a major next step for the approach presented here, which we will further develop in our future work.

5. Conclusions

The ability of deepening and spatially confining the optical region of sensitivity can have a transformational effect on the field of diffuse optics. First, it can enhance the sensitivity to deeper tissues, which is an important goal for a broad class of noninvasive optical measurements of tissue, including the human brain, skeletal muscle, and breast. Second, it can enhance the spatial resolution in diffuse optical imaging, enable novel image reconstruction schemes, and achieve tissue sectioning. The DS approach, reported here for a variety of source–detector configurations, features regions of sensitivity that resemble nuts (compact, round or oblong, mostly confined within the tissue) rather than the banana-shaped regions of sensitivity (curved regions that extend all the way to the source and the detector) that are typical in diffuse optics. The most significant aspect of the nut-shaped regions of sensitivity of the intensity and, even more so, phase dual-slopes is the fact that their maximal sensitivity occurs significantly deeper in the tissue than for single-distance intensity and phase. This result points to the value of the source–detector arrangements and the data processing schemes of dual-slopes for a broad range of applications in diffuse optics, with a renewed emphasis on the importance of phase measurements in frequency-domain spectroscopy.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by NIH Grant No. R01-NS095334.