Multidither coherent optical adaptive technique for deep tissue two-photon microscopy

Abstract

Two-photon microscopy normally suffers from the scattering of the tissue in biological imaging. Multidither coherent optical adaptive technique (COAT) can correct the scattered wavefront in parallel. However, the determination of the corrective phases may not be completely accurate using conventional method, which undermines the performance of this technique. In this paper, we theoretically demonstrate a method that can obtain more accurate corrective phases by determining the phase values from the square root of the fluorescence signal. A numerical simulation model is established to study the performance of adaptive optics in two-photon microscopy by combining scalar diffraction theory with vector diffraction theory. The results show that the distortion of the wavefront can be corrected more thoroughly with our method in two-photon imaging. In our simulation, with the scattering from a 450-μm-thick mouse brain tissue, excitation focal spots with higher peak-to-background ratio (PBR) and images with higher contrast can be obtained. Hence, further enhancement of the multidither COAT correction performance in two-photon imaging can be expected.

1. Introduction

Two-photon microscopy provides a powerful tool to biomedical studies in that it can perform high-resolution imaging with little sample damage and achieve imaging depth up to 1mm.1,2 In two-photon imaging, the strong scattering of the tissue will cause wavefront aberrations and hence distort the optical focus.2,3 To deal with this problem, adaptive optics (AO) technique is widely adopted to compensate the aberrations.4,5,6,7,8 The principle of this technique is to measure the distorted wavefront dynamically and then correct it by an active device, such as a deformable mirror or a spatial light modulator (SLM).9,10 Different approaches have been used in AO to measure the wavefront. One of them is to treat the wavefront as a linear combination of a number of orthogonal modes.11,12,13,14,15,16,17 This approach works well for low-order aberrations but when the wavefront is complex with a large number of high-order aberrations, which is normal in deep tissue imaging,18 it will be difficult for this approach to accomplish both the measurement and the correction.19,20 Another approach divides the wavefront into multiple segmentations and measures each of them independently. The most common way is to measure the wavefront directly by a Shack–Hartmann sensor or digital holography.21,22,23,24,25 The problem of this method in deep tissue imaging is that it is almost impossible to put the wavefront sensor within the tissue and the backscattered light can hardly be used because of the multiple scattering process.26,27,28 Methods that involve indirect measurement of the wavefront have also been developed as more feasible choices. Among them are those methods relying on search algorithms such as genetic algorithms and hill-climbing algorithms.29,30,31,32 However, these methods have disadvantages that they require a large number of iterations to achieve convergence, which will remarkably slow down the imaging speed.11,26 Pupil segmentation method is able to recover diffraction-limited resolution with faster speed.26,33 In this method, the wavefront is measured and corrected with the incident light coming from a single objective pupil subregion each time, so the speed of imaging can still be limited.

To achieve faster imaging speed, a parallel wavefront optimization method based on multidither coherent optical adaptive technique (COAT) has been proposed.34 Multidither COAT is a method formerly used to focus a laser beam through air turbulence.35 When it is applied to correct the distorted wavefront in fluorescence imaging, the main principle is to modulate multiple phase elements of the corrector simultaneously each at a unique frequency and let the modulated beams interfere with the reference beam at the focus to generate a measurable oscillating signal, from the Fourier transform of which the corrective phase values of all modulated phase elements can be determined in parallel. Since the aberrations are corrected in parallel, the speed of two-photon imaging can be much faster with multidither COAT. When multidither COAT is employed, different modulations at distinct frequencies will also interfere with each other. These interferences are likely to overlap with the frequencies we choose for modulation in frequency domain and cause the inaccuracy of the phase value determination. Liu et al. have pointed out that this overlap is avoidable by certain specific frequency choosing method under single-photon condition.36 However, when it comes to two-photon circumstance, the overlap can hardly be eliminated completely by conventional frequency choosing method, which is effective under single-photon condition.

In this paper, we first prove that the overlap will still exist when multidither COAT is applied in two-photon fluorescence imaging with the modulation frequencies chosen by conventional method. Then we put forward our method in which the corrective phase values are determined from the square root of the measurement signal. With our method, the overlap can be eliminated by using the same frequencies previously chosen and the optimal phase compensation pattern can be obtained to achieve more precise wavefront correction for two-photon fluorescence imaging. In order to compare our method with the conventional method, excitation focal spot is applied to evaluate the correction performance of the two methods. In addition, two-photon fluorescence imaging of fluorescent beads as well as mouse brain tissue is also employed for the comparison of the two methods.

2. Principles and Methods

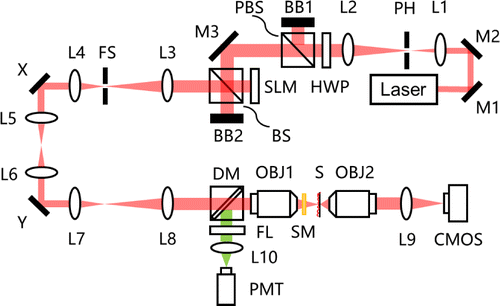

The schematic diagram of the two-photon fluorescence microscope with multidither COAT is illustrated in Fig. 1. A beam with a wavelength of 900nm from the laser source passes through a beam expander to match the dimensions of the SLM. A pinhole is located at the spectrum plane between the two lenses (L1 and L2) to filter the stray light. The intensity as well as the polarization of the beam is adjusted by a combination of a half-wave plate (HWP) and a polarized beam splitter (PBS) before the beam reaches the SLM to be modulated. The SLM is conjugated to the back pupil plane of the objective with lens pairs (L3–8) and two galvanometer mirrors (X and Y). The galvanometer mirrors are applied for two-dimensional raster scanning across the specimen. In order to keep the phase pattern of the SLM stationary during scanning, the conjugation mentioned above is necessary. As the modulated beam reaches the back pupil plane of the objective, it is then focused on the sample by the objective (NA=0.5) through the scattering medium and excites the fluorescence. To observe the focal spot for corrective evaluation, a second objective is adopted to image the focal plane onto a complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) camera. For the fluorescence detection, a dichroic mirror (DM) reflects the fluorescence collected by the objective, which then passes through a filter and is detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT).

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the two-photon fluorescence microscope with multidither COAT: M1–M3, Mirror; L1–L10, Lens; PH, pinhole; HWP, half-wave plate; PBS, polarized beam splitter; BB1–BB2, beam block; BS, non-polarizing beam splitter, 50:50 (R–T); SLM, spatial light modulator; FS, field stop; X&Y, galvanometer mirrors; DM, dichroic mirror; OBJ1, objective lens (UPLFLN 20X, Olympus); OBJ2, objective lens (UPLFLN 40X, Olympus); SM, scattering medium; S, sample; CMOS, complementary metal oxide semiconductor camera (DMK 23UV024, The Imaging Source); FL, filter; PMT, photomultiplier tube.

When the beam is modulated, the SLM is equally divided into a number of subregions and each as a phase element. Half part of the elements goes through a 2π phase variation each at a unique frequency while the other half keeps constant to form a reference. After the corrective phase values of the modulated elements are determined from the feedback signal detected by the PMT, this process is repeated with the constant half and the modulated half exchanged. Finally, as all the phase values are determined, the corrective phase pattern is added on the SLM to achieve final correction.

In the determination of the corrective phases, it is possible that the modulation frequency components overlap with their interferences between one and another. The overlap will result in inaccurate corrective phase values and further cause a decline of the correction performance. To analyze the possible overlap, we assume that E(t) represents the electric field at the focus. Since the focus field is formed by the interference between the modulated light and the reference light, E(t) can be described as

When it comes to two-photon condition, the feedback signal is proportional to the square of the light intensity at the focus, which can be given by

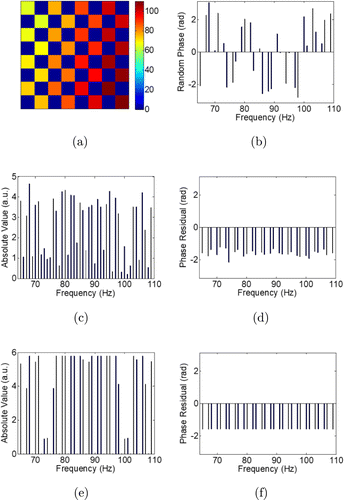

In order to obtain a more applicable method to avoid the overlap without causing extra time cost in multidither COAT for two-photon imaging, here, we propose a new method to calculate the square root of the feedback signal as a new signal to determine the corrective phases. Since the new signal is proportional to the light intensity at the focus rather than the square of it, the interferences caused by the nonlinearity of the two-photon signal can be suppressed and the modulation frequencies used under single-photon condition can also be employed to determine the corrective phases here under two-photon condition without causing any overlap mentioned above. To demonstrate the new method, we choose the modulation frequencies with the requirement of being satisfied. In order to separate some of the interference frequency components from the modulation frequency components so that the suppression effect of our method can be observed obviously. We choose the frequencies to be [64, 65, 67, 68, 70, 71, 73, 74, 76, 77, 79, 80, 82, 83, 85, 86, 88, 89, 91, 92, 94, 95, 97, 98, 100, 101, 103, 104, 106, 107, 109, 110] (Hz) and their corresponding phase element on the SLM is displayed in Fig. 2(a). The initial phase of each element labeled by a modulation frequency is shown in Fig. 2(b). The value of this initial phase is randomly set. When corrective phases are determined by multidither COAT, Fig. 2(c) shows the Fourier transform of the feedback signal without the square root calculation which denotes the conventional method. It is noted that only the part between the minimum and the maximum of the modulation frequency is shown and the subregions corresponding to 64Hz and 110Hz are outside the pupil so the two points are removed. We can see from the figure that the interference components overlap with the modulation components. The Fourier transform of the square root of the feedback signal is given in Fig. 2(e). It is obvious that the interference components that formerly appeared at the non-modulated frequency points are completely suppressed by the new method. We also plot the difference between the initial phases and the calculated corrective phases, namely phase residuals, to evaluate the turbulence from the overlap in the corrective phase determination. In Fig. 2(d), the phase residual changes with the frequency, which reflects the existence of the turbulence using conventional method. When the new method is employed, it can be seen in Fig. 2(f) that the phase residuals are identical, which indicates that the overlap is avoided.

Fig. 2. (a) Phase elements labeled by modulation frequencies on the SLM. (b) Initial phase of each phase element. (c) Fourier transform of the raw feedback signal. (d) Phase residuals corresponding to (c). (e) Fourier transform of the square root of the feedback signal. (f) Phase residuals corresponding to (e).

To further verify the reliability of our method, numerical simulations are conducted in MATLAB using scalar diffraction theory combined with vector diffraction theory.37,38,39,40,41 Objectives of high numerical aperture (NA) are normally employed in two-photon fluorescence imaging. Since the scalar diffraction theory is only applicable when the objective has low NA, the vectorial diffraction theory must be used. However, it is difficult for vectorial diffraction theory to simulate the light propagation through the scattering medium. Therefore, we combine two theories in our simulation by conjugating the scattering medium into a system with a low NA before the objective. By doing this, we can apply the scalar diffraction theory to simulate the light propagation in the system which contains the scattering medium and then simulate the high NA objective focusing process with the vectorial diffraction theory instead. When we conduct the simulation of scalar diffraction theory, the angular spectrum (AS) method is applied, which is a desirable solution to the Helmholtz equation without the use of approximations and can also be conveniently implemented by fast Fourier transform (FFT).

In our simulations, the incident light is linearly polarized with a wavelength of 900nm. The pixel number of the SLM is . The NA of the objective is set to be 0.5. In order to simulate the scattering medium, we take images of a 450-m-thick mouse brain tissue by a two-photon microscope with an optical axial step of 3m and generate 150 phase masks from the images. The phase values on the masks are ranged from 0 to and the value of is controlled to keep consistent with the scattering coefficient of . The phase masks are placed in order maintaining the distance of between every two adjacent masks. The center plane of the phase mask group is located at the middle plane between the objective and the sample. We simulate the scattering effect by adding the phase patterns on these masks to the light field. It is noted that the absorption is neglected here, which is reasonable in deep tissue imaging circumstances.

3. Results

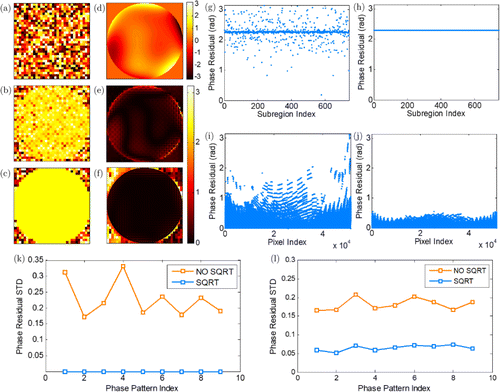

To demonstrate that more accurate wavefront correction can be obtained by our method, we first remove the scattering medium and manually introduce fixed distortions to the incident wavefront by adding different phase patterns on the SLM. To correct these distortions, we set the number of subregions to be with each subregion containing pixels of the SLM. The modulation frequencies are uniformly distributed between 51.2 and 102.3Hz. Two kinds of phase patterns are employed here. As shown in Fig. 3(a), the first kind of phase patterns is generated by setting each subregion to be a random phase value in –. As to the second kind of phase patterns shown in Fig. 3(d), linear combinations of 4th to 21st Zernike modes are used to generate these patterns with each SLM pixel as a phase unit. It is noted that the number of degrees of correction freedom is just enough to entirely compensate the distortions brought from the first kind of phase patterns whereas the distortion of the second kind of phase patterns can only partially corrected. To quantitatively evaluate the wavefront correction, we use phase residual to show the difference between the corrective phases and the phases we previously added. Figures 3(b) and 3(e) show the phase residual distributions of the conventional method when each kind of patterns was added, respectively. The corresponding plots of all the phase residuals inside the pupil are displayed in Figs. 3(g) and 3(i). It can be seen that the phase residuals still have obvious fluctuations and the wavefront cannot be fully compensated after the correction using the conventional method. The phase residual distributions of our method are shown in Figs. 3(c) and 3(f), each corresponding to one phase pattern of the two. Likewise, Figs. 3(h) and 3(j) give the phase residual plots corresponding to Figs. 3(c) and 3(f). For the first kind of phase patterns, the wavefront becomes perfectly flat inside the pupil and the phase residual values are almost identical after the correction using our method. For the second kind of phase patterns, though the number of degrees of correction freedom is not large enough to achieve fully correction, the fluctuation of the phase residual values is greatly reduced compared to the result shown in Figs. 3(e) and 3(i). It is noted that the phase residual values may not tend to 0. The reason is that the ensemble phase of the reference part may not be 0 in the correction. To make the results more convincing, we randomly generate nine patterns for each kind of phase patterns separately and obtain the phase residuals after the correction using the conventional method as well as our method. Then we compute the standard deviations of every group of phase residuals (only the phase residuals inside the pupil are concerned) and plot the results of the first kind of phase patterns in Fig. 3(k) and the second kind in Fig. 3(l). The mean standard deviation of the conventional method is 0.2284 in Fig. 3(k) and 0.1823 in Fig. 3(l). For our method, the number is in Fig. 3(k) and 0.0648 in Fig. 3(l). Apparently, for both kinds of phase patterns, the standard deviations of the phase residuals of our method are much smaller than that of the conventional method, which further indicate that our method is able to determine the corrective phases more accurately and achieve better wavefront correction.

Fig. 3. (a) Phase pattern one generated by setting each subregion to be a random phase value in –. (b) Phase residual distribution of the conventional method for pattern one. (c) Phase residual distribution of our method for pattern one. (d) Phase pattern two generated by linear combinations of 4th to 21st Zernike modes with each pixel as a phase unit. (e) Phase residual distribution of the conventional method for pattern two. (f) Phase residual distribution of our method for pattern two. (g) Plot of (b). (h) Plot of (c). (i) Plot of (e). (j) Plot of (f). (k) Phase residual standard deviation of nine first-kind phase patterns. (l) Phase residual standard deviation of nine second-kind phase patterns.

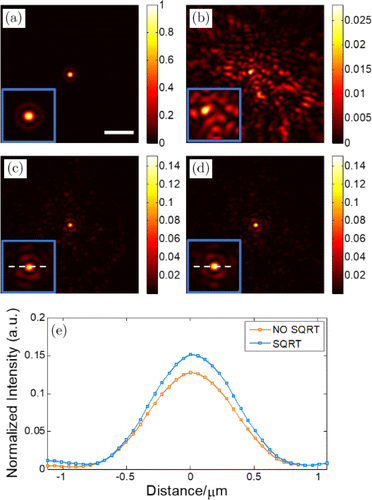

In order to evaluate the enhancement of correction performance brought by our method, we compare the excitation focal spots recovered by multidither COAT correction using conventional method and our method. Here, we divide the SLM into phase elements for correction. The corresponding modulation frequencies are uniformly contributed between 32Hz and 63Hz. Figure 4(a) shows the ideal focal spot formed without the scattering medium. It is noted that the maximum intensity is used to normalize the results. When the scattering medium is inserted into the light path, the focal spot will be scattered into Fig. 4(b). After the correction, the recovered focal spots using conventional method and our method are displayed in Figs. 4(c) and 4(d). The central part of these four figures is shown at the lower-left corner of each figure after magnification so that the focal spot can be seen more clearly. The intensity profiles along the white dashed line, respectively, shown in Figs. 4(c) and 4(d) are compared in Fig. 4(e). It can be seen that the peak intensity of the focal spot of our method is higher and light energy is more concentrated at the focus. For more clear comparison, we use peak-to-background ratio (PBR) of the focal spot as an indicator to assess the correction performance. For the conventional method, the PBR is 24.31. For our method, the number is 29.27, which is 1.2 times that of the conventional method. Therefore, using our method can achieve better correction performance and tighter focus, which may lead to more desirable imaging quality.

Fig. 4. (a) The ideal focal spot formed without the scattering medium (scale bar: 5m). (b) The focal spot scattered by the medium. (c) The recovered focal spot using the conventional method. (d) The recovered focal spot using our method. (e) The intensity profiles along the white dashed lines shown in (c) and (d).

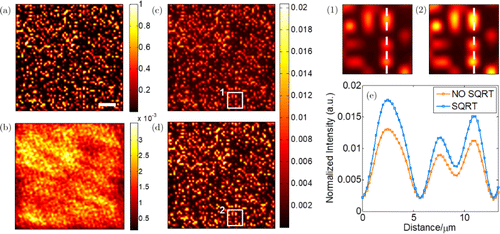

To evaluate the imaging improvement, we also simulate the two-photon fluorescence imaging of a single layer of randomly distributed fluorescent beads. The average diameter of the beads is about and the size of the whole field of view (FOV) is about . Figure 5(a) presented the ideal image without scattering medium. The maximum intensity of the ideal image is also used for normalization. Then, the scattering medium is employed to distort the image into Fig. 5(b), where both the position and the shape of the beads become indistinguishable owing to the aberrations from the medium. To implement correction for the imaging of the whole sample area, we use phase elements with the same modulation frequencies used above and divide the FOV into a number of regions and choose the brightest spot in each region as the guide star. When the conventional method and our method are applied in multidither COAT correction, respectively, the corrected images are correspondingly shown in Figs. 5(c) and 5(d). To compare the two figures in detail, we choose the parts in the white square and show them in (1) and (2). Apparently, the imaging of our method shows better imaging contrast. To quantitatively measure the imaging contrast, we also plot the intensity profiles in Fig. 5(e) along the white dashed line shown in (1) and (2) and calculate the value of imaging contrast by

Fig. 5. (a) The ideal imaging of a single layer of randomly distributed fluorescent beads without the scattering medium (scale bar: 20m). (b) The image distorted by the medium. (c) The corrected image using the conventional method. (d) The corrected image using our method. (1) The image part in the white square of (c). (2) The image part in the white square of (d). (e) The intensity profiles along the white dashed lines shown in (1) and (2).

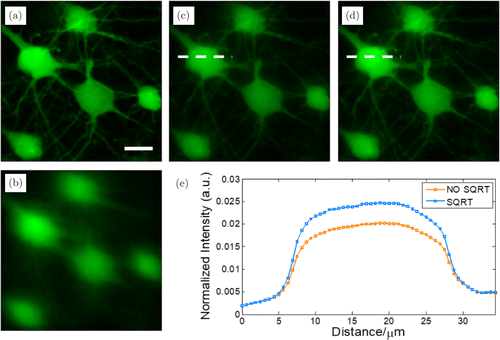

To further demonstrate that better corrected imaging can also be accomplished in biological sample imaging with our method, a slice of mouse brain tissue with the same FOV is used to serve as the imaging sample. Here, we keep the number of phase element and the modulation frequencies unchanged. Figure 6(a) shows the ideal image and Fig. 6(b) gives the image scattered by the scattering medium. It can be seen that the fine structure of the tissue is seriously blurred by the scattering. Figure 6(c) shows the corrected image of the conventional method while the corrected image of our method is presented in Fig. 6(d). The correction method keeps the same as above. The imaging contrast of the image shown in Fig. 6(d) is superior to that of Fig. 6(c). Intensity profiles along the white dashed lines are plotted in Fig. 6(e) from which we can calculate the concrete value of the contrast. The contrast value of the conventional method and our method are 0.83 and 0.86, respectively. It is obvious that sample details can be observed more clearly in the corrected image with our method because of the higher imaging contrast.

Fig. 6. (a) The ideal imaging of a slice of mouse brain tissue without the scattering medium (scale bar: 20m). (b) The image distorted by the medium. (c) The corrected image using the conventional method. (d) The corrected image using our method. (e) The intensity profiles along the white dashed lines shown in (c) and (d).

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we present a method to determine the corrective phases more accurately in multidither COAT correction for two-photon fluorescence imaging. Different from the conventional corrective phase determination method in which the detected two-photon fluorescence intensity signal is served as the feedback signal, our method calculates the square root of the detected signal as a substitute. In this way, the pre-existing overlap between the modulation frequency components and their interferences, which will cause the inaccuracy of the corrective phase determination, can be avoided. As the results demonstrated, better wavefront compensation can be achieved using our method as to different wavefront distortions. For 450-m-thick mouse brain tissue, the PBR of the corrected excitation focal spot using our method is higher than that using conventional method. Furthermore, the imaging contrast of the corrected two-photon fluorescence imaging is also higher for the same scattering medium. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the correction performance of multidither COAT can be improved by our method in two-photon fluorescence imaging. Similar method can also be employed in multidither COAT correction of higher-order multiphoton imaging. This method has the potential to extend the uses of multidither COAT correction in fluorescence imaging and find many applications in biological researches that require high-quality imaging deep into the tissue.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31571110 and 81771877), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province of China (LZ17F050001) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Appendix A

The first item of Eq. (4) is a constant which can be neglected. Therefore, the analysis begins from the second item. The expansion of the second item is presented in Eq. (A.1) with the coefficient is neglected: