Active wavefront shaping for controlling and improving multimode fiber sensor

Abstract

Wavefront shaping (WFS) techniques have been used as a powerful tool to control light propagation in complex media, including multimode fibers. In this paper, we propose a new application of WFS for multimode fiber-based sensors. The use of a single multimode fiber alone, without any special fabrication, as a sensor based on the light intensity variations is not an easy task. The twist effect on multimode fiber is used as an example herein. Experimental results show that light intensity through the multimode fiber shows no direct relationship with the twist angle, but the correlation coefficient (CC) of speckle patterns does. Moreover, if WFS is applied to transform the spatially seemingly random light pattern at the exit of the multimode fiber into an optical focus. The focal pattern correlation and intensity both can serve to gauge the twist angle, with doubled measurement range and allowance of using a fast point detector to provide the feedback. With further development, WFS may find potentials to facilitate the development of multimode fiber-based sensors in a variety of scenarios.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, optical wavefront shaping (WFS) has drawn lots of attention due to its unique ability to control light propagation through/inside complex media, which shows a great potential to revolutionize imaging and light manipulation in biological tissue.1,2,3,4,5,6 Moreover, WFS has been demonstrated to mitigate the mode dispersion and coupling in multimode optical fibers (MMF) by utilizing a spatial light modulator (SLM) to control the wavefront of incident light.7,8 By scanning focus through a multimode fiber directly or revising the transmission matrix, many types of MMF-based endoscopies have been proposed,9,10,11 exhibiting quite a few advantages in brain imaging over fiber bundle. Apart from imaging, WFS also shows lots of interesting applications with multimode fibers, such as nonlinear control12 and communication.13

In this paper, let’s focus on fiber-based sensing application. Optical fibers have not only revolutionized the telecommunication but also been integrated into many fields.14 For example, optical fibers have shown great potentials in security monitoring of physical parameters,15 such as bending, axial stress, transverse load, temperature, and twisting, which is becoming increasingly important and indispensable for bridges, buildings, and many other civil structures. For traditional sensing, fibers with special design and fabrication can serve as a sensor or an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA) to decode the information (such as wavelength shift and intensity variation) from the fiber output. With complex fabrication process and sophisticated operation, fiber sensors can provide a high sensitivity, which, however, also limits broader applications. Fiber specklegram sensors, for example, are rather challenging with traditional methods. Fiber specklegram sensors, by definition, are a class of sensors using the multimode interference analysis to retrieve information of external parameters.16 As known, when light transmits through a multimode fiber, a random speckle pattern can be observed due to the crosstalk of thousands (or even more) of modes inside fiber.17 This process is quite similar to the phenomenon when coherent light goes through a scattering medium and a random speckle pattern is generated due to the scattering-induced phase distortions.18 In both scenarios, scattering has been usually regarded as a nightmare that should be avoided; speckle patterns inside or through complex media has been one of the major noise sources in many applications.

With the development of WFS, scientists have explored the feasibility to control or manipulate diffused light by exploiting the scattering and the corresponding speckle patterns based on their deterministic feature within the medium’s temporal correlation window.19 Measuring the transmission matrix (TM) of the medium is one of the approaches developed.20,21 For an MMF, the TM bridges the input and output modes, and it is deterministic and stable when there are no external perturbations. In other words, external perturbation sources, such as temperature change, twisting, and bending, will cause deformation to the MMF, hence varying the TM. For a regular MMF (e.g., with 0.22 NA, Ø50μm core), it can support thousands of transmission modes, meaning that TM of the MMF can be extremely sensitive to external perturbations. Built upon this philosophy, specklegram sensor has been proposed to detect micrometric variations in displacement,22 vibration,23,24 temperature,25 as well as electrical current.26 Compared with traditional fiber sensors, fiber specklegram sensors possess high sensitivity and the system can be quite simple, making it attractive for many applications. The limitations of specklegram sensors are majorly associated with the utilization of a digital camera to capture the speckle patterns for analysis. Generally speaking, to have more speckle information statistically, a large field of view (FOV) is always preferred. This, however, sees conflicts with the requirement that each speckle grain in the field should be digitally resolved, especially when the bandwidth of the camera and the data transfer are limited. Moreover, since the speckle patterns are spatially nonuniform, which region in the FOV should be chosen and analyzed is not a trivia.

In this paper, we propose a new application of WFS for multimode fiber sensing. Firstly, we briefly introduce a new multimode fiber twist sensor based on specklegram correlation. Then, we show the measuring range of the twist sensor that can be extended with the help of WFS. More importantly, with WFS, light energy can be converged to a spatially confined region, i.e., forming an optical focus. This focus, naturally, is the target for analysis; the above-mentioned FOV issue no longer exists. In the meanwhile, the specklegram phase changes (as usually measured by the correlation reduction) caused by external perturbations can be transferred into intensity changes, which can be directly perceived by a single-aperture detector, such as photodiode. This allows significant increase of detection bandwidth and reduction of cost. Collectively, assistance of active WFS may open a new venue for fiber-based sensors in a variety of aspects.

2. Method and System

When coherent light transmits inside a multimode fiber, the light field Em(r,θ,z) of different modes depend on three cylindrical polar coordinates, r,ϕ, and z, and can be expressed by27

As mentioned earlier, the speckle phenomenon in multimode fiber is similar to that in scattering media, which has been discussed by several groups.28,29,30 The speckle pattern out of a multimode fiber is highly related on the modes in this fiber.31 For a step-index fiber, the number of modes (M) is approximately M=V2/2, where V is associated with the NA, the core radius of the fiber, and the wavelength of light (λ) by V=2πaNAλ.32 Each mode has a different phase velocity as they transmit along different optical paths. At the exit of the MMF (assuming a length of L), the light field at an arbitrary position consists of a sum of a multitude of interferences due to random field contributions of different modes. If light is coherent, the interference between different modes will generate a speckle pattern at the output of the multimode fiber..33 Mathematically, the resultant light field can be expressed by

Let’s take twisting perturbation as the example here. It may lead to speckle pattern phase variation on a macro level. It’s not hard to hypothesize that the larger the twisting angle is, the stronger the specklegram variation will be. Pearson correlation coefficient (CC) between two patterns can be used to quantify such specklegram variations :

Note that, however, such one-to-one mapping between speckle correlation and twisting perturbation may be valid (to be confirmed though through experiments) only when the perturbation is relatively small and within a certain range (to be revealed through experiments). Beyond that range, modal state energy is redistributed, totally changing the landscape of the speckle pattern. The sensing mechanism based on the above-mentioned mapping no longer functions, as the CC is always around 0.

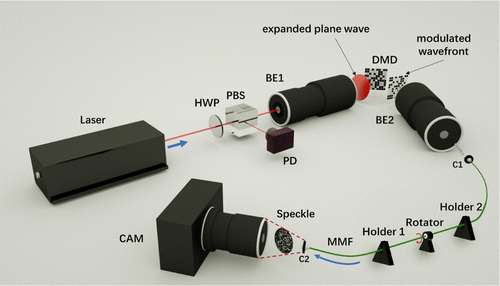

In this study, we first explore how the specklegram correlation can be used to gauge twisting perturbation. Then, WFS is applied to modulate the input light before it enters the multimode fiber; the TM of the fiber is measured in advanced and then is used to generate an optical focal spot at the central of the output field. Based on the focusing pattern, the twist sensing is re-evaluated. The experiment setup is shown in Fig. 1. A continuous laser operating at 532nm (EXLSR-532-300-CDRH, Spectra-Physics, USA) is used as the light source. The laser is coupled into a multimode fiber (0.22 NA, low-OH, Ø50μm core, FG050LGA, Thorlabs, USA) of 1m long to generate a specklegram that contains around 2100 modes after collimation. The MMF is mechanically fixed by Holder 1 and Holder 2, with a distance of 10.35cm between them. A fiber rotator (HFR007, Thorlabs, USA) is used to provide an axial rotation to the MMF. Light output from the MMF is recorded by a CMOS camera (PCO. Edge 5.5, PCO, Germany), with images subsequently transferred to a computer for data analysis in MATLAB (Mathworks, USA). For experiments involved with WFS, a digital micro device (DMD, DLP4100, Texas Instruments Inc., USA) is used to modulate the incident light in order to form an optical focus at the fiber output.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the specklegram twist sensor: C1 and C2, fiber collimator; CAM, digital camera; BE, beam expander; DMD, digital micro device; HWP, half-wave plate; MMF, multimode fiber; PBS, polarized beam splitter; PD, photodiode.

3. Results and Discussion

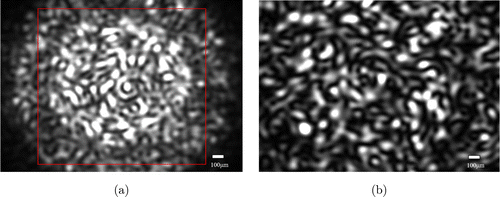

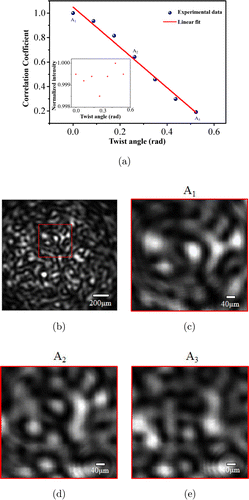

A typical specklegram out from the MMF is shown in Fig. 2(a). The seemingly random speckles caused by the interference of different modes in a circle appears very similar to the speckle pattern outside of a scattering medium (Fig. 2(b)). We chose the inscribed square as the region of interest (ROI) in our study. From the initial loose state, the fiber was gradually twisted by turning the rotator with an interval of 0.087 rad. As discussed above, the fiber output specklegram will change immediately due to the multi-torsional stress zones formed along the fiber axis when the fiber is twisted. Therefore, at each angle position, multiple camera images were recorded and sent to computer for specklegram correlation analysis versus the speckle pattern at the initial state. In Fig. 3(a), the measured speckle CC is shown as a function of fiber twist angle. As seen, the specklegram CC displays a good linearity (R=0.9971, slope at −1.647) with the twist angle, suggesting that the CC changes may be used to gauge the twisting angle of the system. Considering the fiber length between the two mounting stages is 10.35cm, the sensor has a sensitivity of 0.178/(mrad/m) till about 0.524 rad (30∘) of twisting, beyond which the CC decays rapidly and hence can no more precisely reflect the twist angle. In comparison, we also used a photodiode (PDA36A-EC, Thorlabs, USA) to measure the light intensity variation at each twist angle, as shown in the inset of Fig. 3(a), where the relationship between the light intensity variation and the twist angle is hard to interpret.

Fig. 2. Typical speckle patterns from an MMF (a) and a scattering medium (b). The scalar bars represent 100μm. Red box indicates the ROI.

Fig. 3. (a) Measured speckle CC versus fiber twist angle. The relationship between the corresponding light intensity and the twist angle is shown in the inset. (b) The region selected can be zoomed in (indicated in red box) for better view of the details of the speckle patterns (the ROI is not changed). (c)–(e) Three sampled speckle patterns corresponding to A1−3 twist angles in (a).

The proposed specklegram correlation-based twist sensor, however, encounters a limitation on the reliable coefficient working range, which leads a trade-off between the measurable twist angle range and sensitivity. Researchers have developed some methods to mediate the situation for specific applications. For example, one method is to tune the size or area of the ROI,16 as every fiber output mode has different sensitivity to the same perturbation. Therefore, varying the ROI can lead to different sensitivities. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that using a signal processing method to remove some low-frequency or high-frequency components, one can increase or decrease the sensitivity, respectively.35 In this study, optical WFS technique is applied to the MMF sensor to dynamically tune the measurement sensitivity and range from a new perspective that has thus far not been introduced to the field. As we know, the inherent multiple scattering nature of light in biological tissues results in many challenges to optical microscopic techniques, such as low intensity and compromised resolution,36,37 at depths in tissue. In order to suppress medium’s turbidity, optical WFS has been proposed to manipulate the propagation of light so as to achieve controlled optical focusing and imaging within thick scattering media.2 This technique has also been used to control the mode coupling in multimode fibers.38,39 Since the speckle patterns as shown in Fig. 2 are generated from the interference and coupling among modes, WFScan thus pose extra active mode control to improve the performance of the specklegram-based sensor.

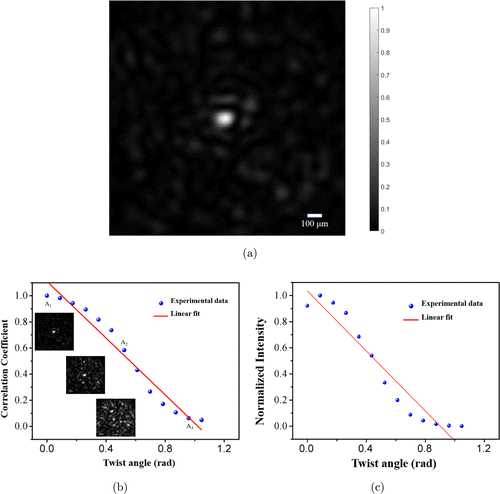

In experiment, we used a binary 1920×1080 pixels DMD (32×32 independent controls were assigned) to spatially shape the wavefront of light before it enters the fiber.40,41 The Hadamard basis was used to construct the modulation to the incident wavefront in order to measure the TM of the MMF.42 When a binary pattern was displayed on the DMD screen, the corresponding optical field (output) was recorded by a camera and sent to PC subsequently. After all DMD patterns were enumerated, the TM could be calculated following a method described in Ref. 40. Based on the measured TM, a special DMD pattern was computed and transferred onto the DMD, applying an active mode control to the MMF. This can generate an optical focus at the camera plane shown in Fig. 4(a), and the focal spot diameter is around 100μm, agreeing with the averaged size of the speckle grains within the view. After that, different twist angles were applied onto the multimode fiber; the corresponding speckle patterns were recorded for each twist angle. As seen in Fig. 4(b), the peak-to-background ratio (PBR, defined by the ratio between the focal intensity and the averaged intensity of the background) of the focal spot decreases with the twist angle, and so the CC of each speckle pattern with respect to the initial one (i.e., before the fiber was twisting) decreases. The trend is quite similar to what has been observed from the nonWFS sensor (Fig. 3(a)) that yields a maximal twist angle of ∼0.524 rad (30 degrees). With wavefront shaping, however, the measurement range is doubled to ∼1.047 rad (60 degrees). Unlike existing approaches such as changing the ROI or spectrally filtering the output specklegrams to achieve a dynamic measurement range, WFS enables extra mode control that can actively modify the sensor and extend its applications. In addition, as discussed above, the total output intensity of MMF remains nearly constant, which means it is hard to measure the perturbations by using some high bandwidth detectors such as photodetectors. When WFS was applied to control the light propagation in multimode, the complex changes of mode interference can be transferred to simple intensity changes. As the result shown in Fig. 4(c), there is a linear relationship between the twist angle and focus intensity. Therefore, WFS can not only be used for controlling the measuring range but also transfer the external perturbation (phase change) to output intensity change, which indicates a great potential for high-speed detection. Nevertheless, this idea is still in its infancy, and there are quite a few challenges that needs to be overcome (e.g., the system is also sensitive to environment perturbations) to make it function well in different scenes.

Fig. 4. (a) An optical focus with a PBR of ∼53 was generated at the exit plane of the fiber through wavefront shaping. (b) With active mode control of wavefront shaping, the measurement range of the MMF twist sensor based on the decay of the CC can be almost doubled. Inset: Speckle patterns for three representative twist angle positions, i.e., A1, A2, and A3. (c) With WFS, the specklegram changes under external perturbations can be transferred into and measured by intensity change at the focus.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we proposed a novel and straightforward twist sensor based on the specklegram correlation of multimode fiber outputs, and we pilot explored the efficacy of using optical WFS as active method to dynamically tune the performance of the sensor. The linear relationship between the twist angle and the focal intensity shows a great potential for high temporal resolution sensor design. Moreover, the measurement range of MMF specklegram sensors is doubled, and the detection temporal resolution can be significantly improved by employing a point detector (such as a fast photodiode) to replace the CMOS camera that has a limited frame rate.

Before concluding, two more aspects need to be pointed herein. First, the WFS implementation in this study was based on a regular DMD. Since the DMD is a broadband device, the proposed method can be suitable for a wide range of wavelengths, although only 532nm was explored in this study. However, it should be noted that light of shorter wavelength generates more modes via the MMF, leading to smaller speckle grain size and hence more optical modes are within the same field of view. Under this situation, the CC of the focal pattern decreases faster, as the focal point is the result of in-phase interference of numerical modes. Second, in our TM method in this study, all modulating patterns were generated by the computer and uploaded to the DMD before experiment. The number of patterns is determined by the number of pixels that we want to use in TM model. For example, if we want to divide the input light into 4096 segments, 8191 patterns need to be uploaded to the DMD. During the optimization, these patterns were displayed on the DMD screen sequentially, and the corresponding speckle patterns were recorded one by one. In our study, the DMD was tuned to function at rates of up to 22.5kHz, approaching the upper limit of the device. However, due the limited frame rate of the used CMOS camera, it took much longer to finish the process. On other hand, some time was needed for data transfer and matrix computation. Therefore, it took more than 10s in this study to form an optical focus. For such a timing issue, however, a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) can employed to significantly accelerate the computation (for example, down to 40ms as reported in Ref. 43). Moreover, if a more advanced DMD (e.g., more independent pixels and faster frame rate) is available, a brighter focusing can be formed within 1 s, especially if a fast point detector (e.g., photodiode) is used to provide the feedback. Collectively, with further engineering, the proposed wavefront shaping-assisted MMF may benefit wide applications or inspire new approaches within and beyond sensing. For example, the improvement of temporal resolution allows one to sense some fast and broadband signals, such ultrasound, small environment perturbations, deep-tissue fluorescence imaging, and fiber-based optical coherent tomography (OCT) signals.44,45

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

Acknowledgments

The work has been supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (No. JCYJ20170818104421564), the Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission (No. ITS/022/18), the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (No. 25204416), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81671726 and 81627805). Tianting Zhong and Zhipeng Yu contributed equally to this work.