Rapid label-free SERS detection of foodborne pathogenic bacteria based on hafnium ditelluride-Au nanocomposites

Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials have captured an increasing attention in biophotonics owing to their excellent optical features. Herein, 2D hafnium ditelluride (HfTe2)2), a new member of transition metal tellurides, is exploited to support gold nanoparticles fabricating HfTe2-Au nanocomposites. The nanohybrids can serve as novel 2D surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) substrate for the label-free detection of analyte with high sensitivity and reproducibility. Chemical mechanism originated from HfTe2 nanosheets and the electromagnetic enhancement induced by the hot spots on the nanohybrids may largely contribute to the superior SERS effect of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites. Finally, HfTe2-Au nanocomposites are utilized for the label-free SERS analysis of foodborne pathogenic bacteria, which realize the rapid and ultrasensitive Raman test of Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella with the limit of detection of 10 CFU/mL and the maximum Raman enhancement factor up to 1.7×108. Combined with principal component analysis, HfTe2-Au-based SERS analysis also completes the bacterial classification without extra treatment.

1. Introduction

Bacterial foodborne disease caused by microorganism-contaminated food or water has inspired an increasing concern about food safety issues.1 Common pathogenic bacteria include Salmonella, pathogenic Escherichia coli (E. coli), Listeria monocytogenes (Listeria), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), etc.2 Quick and in situ detection of bacteria can help assess the bacterial infectivity of food and thus ensure food safety. At present, the gold standard for the detection of bacteria mainly relies on colony growth strategies, including bacterial enrichment culture, isolation of pathogen, biochemical and/or serological tests, which indicate the time-consuming, complicated and technique-demanding procedures.3 Therefore, it is of potential value to explore an easy, rapid but effective method for the accurate identification of bacteria.

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has proven to be a highly sensitive analytical technique that can specifically identify the molecular fingerprints of analyte.4 When the sample is close to or adsorbed on plasma nanostructures (Au, Ag, etc.), the Raman signals of the target analyte can be improved by several orders of magnitude compared to conventional Raman spectroscopy.5,6,7 In recent years, SERS has also shown great promise in the field of detecting microorganisms, and different SERS methods have been reported for studying the detection of low-concentration viruses.8,9 For example, Guo et al. developed a tape-like SERS substrate for the point-of-care test of wound infectious pathogens (Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus), which allowed the whole detection completed within 8h.10 Huang et al. integrated SERS technique with microfluidic microwell device, resulting to a rapid antibiotic susceptibility test on E. coli and S. aureus.11 The electromagnetic and chemical mechanisms are the two generally accepted mechanisms for the Raman enhancement of SERS substrate. The electromagnetic mechanism (EM) is based on local surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of nanostructure, while the chemical mechanism (CM) depends on the charge transfer between the substrate and the analyte. Therefore, strategies for fabrication of novel SERS substrates that can potently inspire both EM and CM may be of great value for the ultrasensitive SERS analysis of bacteria.12

Recently emerging two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials have attracted tremendous attention for biomedical applications due to their extraordinary physicochemical properties and biocompatibility.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 The most prominent feature of 2D nanostructures is the ultra-large surface area which allows them as burgeoning carriers for drugs, biomolecules or nanopariticles.20,21,22,23 2D nanomaterials also show outstanding optical features that enable the theranostic applications, such as fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging, photothermal and photodynamic therapy.24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 In addition, the low cost of preparation and simplicity of functionalization facilitate the popularization of 2D nanomaterials in biomedicine.34,35,36 More interesting, 2D nanostructures have also been proven to be the novel SERS substrates for biosensing. The first work was performed in 2010 by Ling et al., where the Raman signals of dye molecules were enhanced by several times after deposited onto graphene sheet.37 Similar phenomena are also observed in black phosphorus, triclinic rhenium disulfide, hexagonal boron nitride and molybdenum disulfide, which is considered as the CM effect originating from the charge transfer between 2D nanosheet and the dye molecules.38,39 However, the limits of detection (LODs) and Raman enhancement factors (EFs) of the above materials are too limited to be utilized for biosensing. With the subsequent development of 2D materials, more and more powerful nanostructures with better SERS activities have been discovered.40,41,42,43 Among them, transition metal tellurides (TMTs) have exploited to be superior 2D SERS substrates as EFs induced by TMTs are several orders of magnitude higher than that induced by single elemental 2D materials.44,45 For further SERS bioanalysis, 2D material-noble metal nanocomposites are proposed, whose SERS activities originate both from the electromagnetic enhancement of deposited metallic nanoparticles and chemical enhancement of 2D nanosheet.46,47,48,49

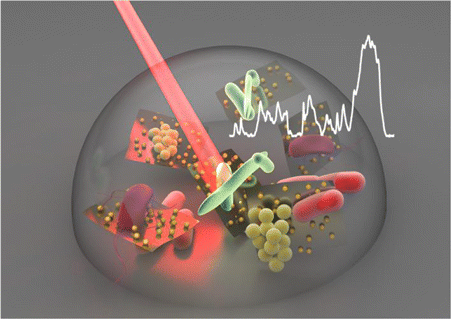

Herein, we report a label-free SERS detection and discrimination of foodborne pathogenic bacteria based on a novel 2D SERS substrate consisting of gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) and 2D hafnium ditelluride (HfTe2) nanosheets (Fig. 1). The HfTe2-Au nanocomposites are acquired by a one-pot liquid phase reduction reaction using sodium citrate as the reductant and poly-L-lysine as the stabilizer without any other chemicals or irradiation. In situ formation of Au NPs on HfTe2 nanosheets is conducted by the reductant in the presence of positive-charged poly-L-lysine. The nanocomposites, due to the attachment of gold nanoparticles, exhibit stronger LSPR which causes a higher EM field located at the gaps of nanoparticles and leads to more abundant hot spots for generating more intense Raman signals in comparison to non-adsorbed Au NPs. HfTe2 nanosheet also provides additional chemical enhancement to the analyte. On the basis of the combined merits, the utilization of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites for SERS sensing of four common foodborne bacteria (E. coli, Salmonella, Listeria, and S. aureus) is carried out, which achieves a low LOD value of 10 CFU/mL and the maximum Raman EF of 1.7×108.

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the SERS sensing of foodborne pathogenic bacteria based on HfTe2-Au nanocomposites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Methylene blue (MB) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Bulk HfTe2 crystals were obtained from SixCarbon Tech Co. Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4⋅4H2O), sodium citrate and poly-L-lysine hydrobromide were obtained from China National Medicine Corporation (Shanghai, China). Ultrapure water (18.2MΩ, Milli-Q System, Millipore, USA) was used in all experiments.

2.2. Preparation of HfTe2-Au composites

HfTe2 nanosheets were prepared by liquid stripping using probe ultrasound (600W, 8h) combined with water bath ultrasound (400W, 10h). Then, HfTe2-Au nanocomposites were synthesized as follows: 100μL as-obtained HfTe2 nanosheets, 40μL of 25mM HAuCl4 and 200μL of 5mM poly-L-lysine solution were dissolved into 15mL deionized water under the condition of ultrasonication for 15min, followed by heating to boiling. 100μL of 10mM sodium citrate was dropwise added into the above solution under continually stirring for 30min. The as-prepared nanocomposites were washed three times with deionized water by centrifugation (6500 rpm, 10min).

2.3. Characterization

The morphology of HfTe2 nanosheets and HfTe2-Au was characterized by a 200kV transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL, JEM-2010HR, Japan). The height of the nanomaterials was observed by an atomic force microscope (AFM, FSM-Nanoview, Fishman, China). The ultraviolet-visible-near infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) absorbance spectra of the nanoparticles were conducted on an absorption spectrometer (UV-6100S, MAPADA, China). Raman spectra were collected using Renishaw inVia microspectrometer (Renishaw, England) under a 785nm diode laser excitation.

2.4. SERS experiments

MB was selected as probe molecules to study the SERS activities of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites. MB at different concentrations were deposited onto the SERS substrate (on SiO2 wafer) by spin coating, and then detected using Renishaw inVia Raman spectroscopy under the excitation of 785nm laser (spectral coverage ranges from 613cm−1 to 1725cm−1). The laser power was 1mW and the integrated time was 5 s. All experiments were performed independently five times. For bacterial SERS analysis, E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella and Listeria, precultured in Luria-Bertani medium, were water-washed three times and resuspended in water at the concentrations of 101–108 CFU/mL. After dropped onto HfTe2-Au substrate, the Raman signals of bacteria were recorded under the Raman spectroscopy.

2.5. Electromagnetic field distribution simulations

The electromagnetic field distribution around Au NPs and HfTe2-Au nanosheets was simulated using finite difference time domain (3D-FDTD) method. The diameter of Au NPs and the thickness of HfTe2 nanosheets were set according to the average size measured by TEM and AFM analysis. A total-field scattered-field light source was used for light excitation from the top (+Z direction, 785nm). The structure was surrounded by perfectly matched layer (PML) boundary conditions in the XYZ direction to absorb all scattered waves. A power monitor near the nanostructure was placed to record broadband near-field enhancement results. In order to obtain high-precision results, mesh accuracy and min mesh step were set 4nm and 0.25nm, respectively. In addition, mesh gaps were set at all gaps and a mesh size of 0.5nm was used.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of nanostructures

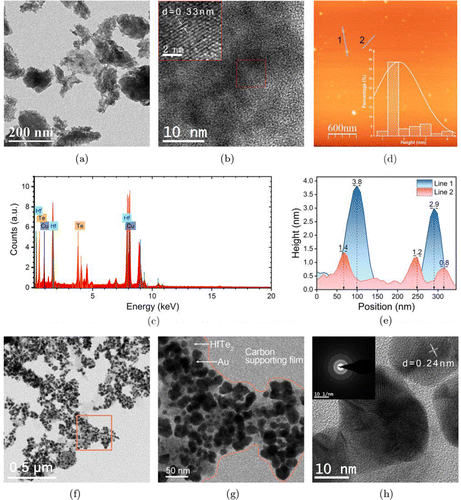

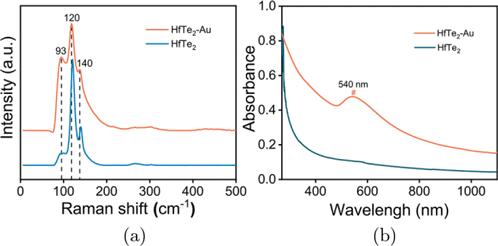

The TEM image of HfTe2 nanomaterials is shown in Fig. 2(a), where typical few-layered nanosheets can be observed. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) of HfTe2 nanosheets shows the crystalline structure with a lattice spacing of 0.33nm (Fig. 2(b)). The EDX spectrum confirms the element content (Hf and Te) in the HfTe2 nanosheets (Fig. 2(c)). The AFM image shows the thickness of HfTe2 nanosheets with an average height of about 2nm (Figs. 2(d) and 2(e)). Figure 2(f) displays the TEM image of nanocomposites after in situ reduction of HAuCl4 on 2D nanosheets. It is clearly noticed that a large number of Au NPs (higher contrast) are attached on the HfTe2-Au nanosheets (lower contrast), and almost all nanoparticles are confined to the carriers, indicating the effective formation of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites. The higher magnification TEM image of HfTe2-Au nanosheets further visually shows the composite of HfTe2 nanosheets and Au nanospheres, but the distribution and morphologies of Au NPs on HfTe2 nanosheets are heterogeneous (Fig. 2(g)). The SAED pattern and HRTEM image (Fig. 2(h)) illustrate the crystalline structures of Au NPs in the nanocomposites. The Raman spectra of the nanostructures show the characteristic Raman peaks of HfTe2 at 100–200cm−1, indicating the presence of HfTe2 in the nanocomposites (Fig. 3(a)). As shown in Fig. 3(b), the UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectrum of HfTe2 nanosheets displays a decreasing optical absorption from UV to NIR region. After Au NPs deposition, a typical absorption peak around 540 nm emerges in the spectral line of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites.

Fig. 2. (a) TEM image and (b) HRTEM image of HfTe2 nanosheets. (c) EDX pattern of HfTe2 nanosheets. (d) AFM image with the corresponding thickness distribution (inset) and (e) height profiles of HfTe2 nanosheets. Low-magnification (f) and higher-magnification TEM images of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites (g). (h) HRTEM image with the corresponding SAED pattern (inset) of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites.

Fig. 3. (a) Raman spectra and (b) UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra of nanomaterials.

3.2. SERS activity of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites

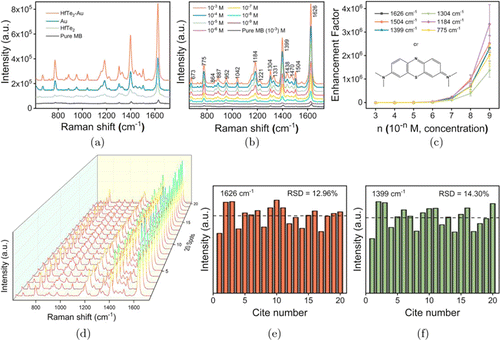

We used MB as a Raman probe molecule to study the SERS performance of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites. As shown in Fig. 4(a), the Raman signals of MB molecules are significantly enhanced by HfTe2 nanosheets, Au NPs and HfTe2-Au nanocomposites, respectively, where the typical characteristic bands at 1626cm−1, 1399cm−1 and 1184cm−1 are attributed to the N-phenyl stretching vibration mode, C–H bending vibration and the skeleton vibration of the ring, respectively.50,51 Compared with bare Au NPs and HfTe2 substrates, the SERS spectrum of MB induced by HfTe2-Au shows the most intense signals, indicating the optimal SERS activity. Then we explored the HfTe2-Au-based SERS analysis of MB molecules at the concentration decreasing from 10−3 to 10−9 M. As can be seen from Fig. 4(b), intense but concentration-dependent SERS signals are observed, and the characteristic Raman peaks of MB can still be clearly identified at the minimum concentration (10−9 M). In order to quantitatively analyze the SERS effect of HfTe2-Au nanomaterials, we calculated the EF according to the following equation :

Fig. 4. (a) Raman spectra of MB deposited on HfTe2-Au nanocomposites, Au NPs, HfTe2 nanosheets and SiO2 wafer, respectively. (b) SERS spectra of different concentrations of MB molecules on HfTe2-Au substrate. (c) The EF values of six typical Raman peaks of MB (on HfTe2-Au substrate) at different concentration levels. (d) SERS spectra of MB on HfTe2-Au substrate collected from random twenty positions. (e, f) The intensity distribution of SERS peak at 1626 and 1399cm−1 in the above 20 spectra.

The SERS reproducibility of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites was further investigated. We randomly collected 20 SERS lines of MB molecules on the HfTe2-Au substrate. As shown in Fig. 4(d), the spectral patterns and intensities of the SERS signals of MB molecules after deposited onto HfTe2-Au substrate are basically consistent. Then, the intensity of SERS band at 1626 and 1399cm−1 was used to measure the relative standard deviation (RSD) value, which was calculated to be 12.96% and 14.30%, respectively (Figs. 4(e) and 4(f)), indicating a good SERS reproducibility of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites as the novel SERS substrate.

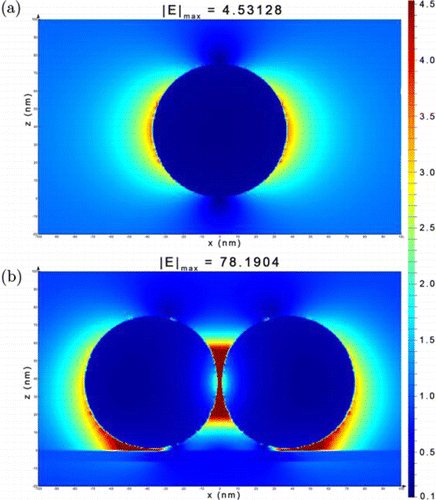

3.3. Raman enhancement mechanism

The superior SERS performance of HfTe2-Au substrate may be attributed to the following reasons: First, HfTe2 nanosheets play a role of novel 2D SERS substrate that offers the chemical enhancement to the Raman signals of dye molecules (Fig. 4(a)), which is consistent with other telluride-based 2D nanomaterials reported by Tao et al.44 Second, the surface enrichment of dye molecules on the nanosheets may also contribute to the strong SERS signals.52 Third, the 2D nanosheets can serve as the support for the in situ growth of Au NPs, where the metal nanoparticles range closely (Fig. 2(f)), leading to plentiful hot spots appeared in the gaps. It has been recognized that hot spots are closely related to the electromagnetic Raman enhancement of a SERS substrate.4 To verify this, 3D-FDTD simulation was conducted to describe the electromagnetic field distribution around the SERS substrate. Figure 5(a) shows the electromagnetic field distribution around a discrete Au NP, where the signals are mainly distributed on both sides of Au NP perpendicular to the laser irradiation, and gradually attenuate along the direction away from the nanoparticle. When two adjacent Au NPs deposited on HfTe2 nanosheet, the distribution of electromagnetic field changes dramatically (Fig. 5(b)). The hot spots appear in the interval between the two Au NPs, as well as the joints between Au NPs and the nanosheet, in which the local electromagnetic field values are measured to be several tens of times stronger than that of single Au NP. Overall, a complex mechanism may contribute to the superior SERS effect of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites.

Fig. 5. 3D-FDTD simulation of the electromagnetic field distribution around (a) a discrete Au NP and (b) two adjacent Au NPs on HfTe2 nanosheet, respectively.

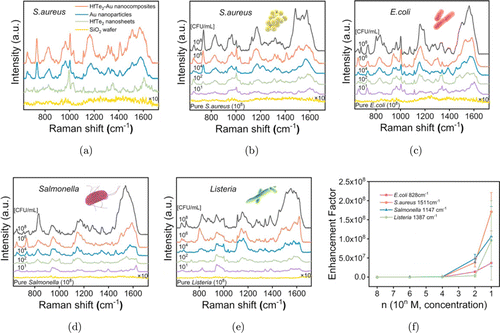

3.4. Label-free SERS analysis of foodborne pathogenic bacteria

Encouraged by the outstanding SERS activity of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites, we finally performed the rapid Raman test of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. As shown in Fig. 6(a), the Raman signals of S. aureus are significantly enhanced by HfTe2-Au nanocomposites, Au nanoparticles and HfTe2 nanosheets, respectively. In comparison to others, the SERS signals induced by HfTe2-Au substrate are the most intense, which is consistent with the data described in Fig. 4(a). Figures 6(b)–6(e) demonstrate the SERS spectra of four types of bacteria (S. aureus, E. coli, Salmonella and Listeria) at different concentrations induced by HfTe2-Au substrate. It can be obviously noticed that the normal Raman spectra of the four bacteria are hardly detected even at the highest concentration (108 CFU/mL). The Raman signals of bacteria significantly enhanced after deposited onto HfTe2-Au nanocomposites, where abundant SERS peaks assigned to biochemical components of bacteria can be observed. Even if the bacterial concentration decreases to 10 CFU/mL, the main Raman bands of bacteria can still be evidently noticed. The LOD value (10 CFU/mL) of this SERS technique is much lower than those list in literature, indicating a promising potential for the bacterial detection.53 Then, the EFs of four bacteria were measured to quantitatively describe the SERS effect. The EFs of E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella and Listeria are calculated to be 3.7×107, 1.7×108, 1.1×108 and 9.6×107, respectively (Fig. 6(f)).

Fig. 6. (a) Raman spectra of S. aureus deposited on HfTe2-Au nanocomposites, Au nanoparticles, HfTe2 nanosheets and SiO2 wafer, respectively. SERS spectra of (b) S. aureus, (c) E. coli, (d) Salmonella and (e) Listeria on HfTe2-Au substrate at the concentrations of 108, 106, 104, 102 and 101 CFU/mL. (f) The EF values of typical Raman peaks of four bacteria on HfTe2-Au substrate.

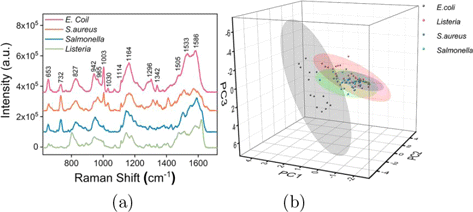

The HfTe2-Au-based SERS spectra also reveal the rich molecular fingerprint information of the bacteria. The SERS signals of E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella and Listeria share a large number of Raman bands although their spectral patterns show some differences (Fig. 7(a)). For example, 653cm−1 (C–C twisting in tyrosine), 732 cm−1 (adenine), 827cm−1 (tyrosine ring breathing), 942cm−1 (C–C stretching in α-helix), 965cm−1 (C–C stretching in protein), 1003cm−1 (phenylalanine ring breathing), 1030cm−1 (C–H in-plane phenylalanine), 1114cm−1 (C–N stretching in protein), 1164cm−1 (C–C/C–N stretching in protein, phenylalanine), 1296cm−1 (CH2 deformation in lipid, adenine, cytosine), 1342cm−1 (adenine), 1505 and 1533cm−1 (adenine, cytosine, guanine), 1586cm−1 (Amide II, phenylalanine, tyrosine, adenine, guanine).54,55 Finally, we used the principal component analysis (PCA) to discriminate the SERS spectra of four bacteria. As displayed in Fig. 7(b), a relatively clear separation of E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella and Listeria is achieved, revealing a potential of HfTe2-Au-based SERS technique for rapid test and label-free classification of foodborne pathogenic bacteria.

Fig. 7. (a) Comparison of SERS spectra of four foodborne pathogenic bacteria on HfTe2-Au substrate. (b) Three-dimensional PCA scores plot of E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella and Listeria.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have explored the new 2D HfTe2 nanosheets for the fabrication of HfTe2-Au nanocomposites. The nanohybrids display outstanding SERS activity that can be used as a novel 2D SERS substrate for sensing with high sensitivity and reproducibility. HfTe2-Au nanocomposites are then utilized for the rapid SERS test of four common foodborne pathogenic bacteria. The LOD value of HfTe2-Au-based SERS analysis for E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella and Listeria is measured to be 10 CFU/mL with the maximum Raman EF of 1.7×108. Bacterial classification is also achieved by SERS technique combined with PCA algorithm. The SERS technique based on the nanocomposites consisting of 2D material and metal nanoparticles supplies new avenue for the rapid and point-of-care test of foodborne pathogenic bacteria.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11874021, 61675072 and 21505047), the Science and Technology Project of Guangdong Province of China (2017A020215059), the Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou City (201904010323 and 2019050001), the Innovation Project of Graduate School of South China Normal University (2019LKXM023), and the Natural Science Research Project of Guangdong Food and Drug Vocational College (2019ZR01).