Forces of RBC interaction with single endothelial cells in stationary conditions: Measurements with laser tweezers

Abstract

Red blood cells (RBCs) are able to interact and communicate with endothelial cells (ECs). Under some pathological or even normal conditions, the adhesion of RBCs to the endothelium can be observed. Presently, the mechanisms and many aspects of the interaction between RBCs and ECs are not fully understood. In this work, we considered the interaction of single RBCs with single ECs in vitro aiming to quantitatively determine the force of this interaction using laser tweezers. Measurements were performed under different concentrations of proaggregant macromolecules and in the presence or absence of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) activating the ECs. We have shown that the strength of interaction depends on the concentration of fibrinogen or dextran proaggregant macromolecules in the environment. A nonlinear increase in the force of cells interaction (from 0.4 pN to 21 pN) was observed along with an increase in the fibrinogen concentration (from 3mg/mL to 9mg/mL) in blood plasma, as well as with the addition of dextran macromolecules (from 10mg/mL to 60mg/mL). Dextran with a higher molecular mass (500kDa) enhances the adhesion of RBCs to ECs greater compared to the dextran with a lower molecular mass (70kDa). With the preliminary activation of ECs with TNF-α, the force of interaction increases. Also, the adhesion of echinocytes to EC compared to discocytes is significantly higher. These results may help to better understand the process of interaction between RBCs and ECs.

1. Introduction

Endothelial cells (ECs) are the cells that line the interior surface of blood arteries, veins and capillaries. ECs interact directly with blood cells: platelets, leukocytes and red blood cells (RBCs). Many hemorheological disorders in the human body are accompanied by increased adhesion of blood cells both to each other and to the vascular endothelium. In a number of diseases, for example diabetes mellitus, an increase in the forces of interaction of RBCs with each other is observed, which leads to an accelerated growth of RBCs aggregates and to an increase in blood viscosity and a decrease in its fluidity.1,2 One consequence of this pathologic condition is the formation of blood clots in the vessels.3 In this case, blood cells interact stronger with ECs attaching to them.4,5,6 An important role of the adhesion process is played by the endogenous molecular components of the blood involved in the interaction of cells. One of the most important of them is fibrinogen.7 An increased content of fibrinogen leads to changes in the rheological properties of blood due to an increase in plasma viscosity, aggregation of RBCs and thrombus formation. Also, fibrinogen influences the elasticity of blood vessels and the integrity of the ECs layer.8,9 It is known that in diabetes mellitus and coronary heart diseases the content of fibrinogen in the blood increases. Fibrinogen as the high molecular mass adhesive protein in blood plasma also is a marker of inflammation.10,11 Polymerizing during the formation of blood clots, fibrinogen forms a fibrin network that binds blood cells and the vascular endothelium. Also, the adhesion of blood cells can be influenced by exogenous antiaggregants and proaggregants such as polysaccharide dextran of different molecular masses, which are often used in clinical and experimental medicine.12,13

Presently, the mechanisms of adhesion of blood cells to each other and to the vascular endothelium, in particular during thrombus formation, are not fully understood.14,15 The quantitative measurement of the forces of cells adhesion is of great importance for the study of the mechanisms of their interaction.

Among many substances leading to endothelial dysfunction, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) plays a central role. TNF-α is involved in the early stages of inflammation.16 Elevated levels of inflammatory TNF-α are often present in conditions associated with cardiovascular risk. One of the consequences of an increased level of the cytokine TNF-α is the expression of adhesion molecules.17 TNF-α can lead to apoptosis of ECs, as well as the generation of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide.18,19,20

In this work, the strength of the interaction between RBCs and individual ECs was measured under various conditions in vitro using laser tweezers (LT) that make it possible to characterize the interaction of the cells without mechanical contact. In order to ensure the minimization of the heating and photodamage effect of laser radiation on the live cells, the laser wavelength was chosen corresponding to the near infrared range, which is characterized by the minimum absorption by the cells.21,22

Under physiological conditions, i.e., in the human body, RBCs interact not with single ECs and not in stationary state, but with a monolayer of ECs in flow. The present study is a preliminary stage designed to demonstrate the possibility of quantitative measurement of the interaction forces between RBCs and ECs in order to determine the force ranges under the influence of various factors. In this work, we do not claim the physiological relevance of measurements with individual cells. In future, we plan to make measurements with monolayers of adherent ECs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Red blood cells

The experiments were performed with blood drawn from 10 healthy donors 20–30 years old (average age of 24 years) and 15 patients suffering type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) 24–83 years old (average age of 58.4 years). The patients were enrolled in the cardiology department of Medical Scientific Educational Centre (MSEC) of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University. Measurements were performed with fresh whole blood samples, drawn from the cubital veins and collected into vacuum containers with EDTA K2 (2-substituted potassium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) at a concentration of 1.5mg/mL to exclude blood clotting. The RBCs were separated from the whole blood as follows: 2mL whole blood samples were centrifuged (Eppendorf MiniSpin, Germany) at 180 × g for 10min, and the plasma was removed using a microsampler. To obtain plasma without platelets and leukocytes, it was additionally centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10min. Platelet-free plasma was used as the main RBC suspension medium in LT experiments. The RBCs were diluted in platelet poor plasma in a ratio of 1:1000. With this dilution, the distance separating the nearby noninteracting cells is large enough to ensure the absence of their effect on the measurement process. The prepared sample was placed into a minicuvette specially designed for the measurements with LT as described herebelow in Sec. 2.4.

In our experiments, we used 2 types of RBC: RBC with regular shape (discocytes) and irregular shape (echinocytes). Echinocytes can be found in in vitro conditions under normal after changing ion concentration in the cell environment and after some pathologies, e.g., T2DM.23 In most of our experiments, we used discocytes from the blood of healthy volunteers and echinocytes from the blood of patients suffering T2DM.

2.2. Endothelial cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were provided by the unique scientific installation “Collection of cell cultures” of the Center for Collective Use of the Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology of Russian Academy of Sciences. Only the cells of 3–6 passages were used for the experiment. In the sample cuvette, the individual ECs adhered to the bottom and thus were immobile. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) was added to the medium in concentration 20ng/mL one day before the experiment to simulate the inflammation under experimental conditions.

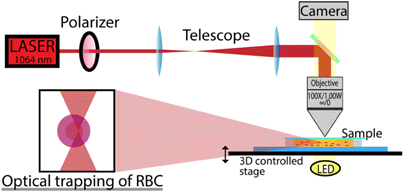

2.3. Laser tweezers

In order to measure the interaction forces of single RBCs with individual ECs without mechanical contact, we used home-made LT,24,25,26,27 in which the Nd:YAG laser (Shanghai Dream Lasers Technology) with a wavelength of 1064nm was implemented. The power of the initial 500mW laser beam with the Gaussian intensity profile after passing through the entire optical system was reduced to 0–27mW in its waist. Then the beam passed through a polarizer for controlling its power and a beam expander that is needed for the objective lens to focus the beam into a spot of the smallest diameter. Then the beam entered the system, which is an optical microscope equipped with a 100 × water-immersion type objective with a numerical aperture NA = 1.0 and a working distance of 1mm (Olympus LUMPlanFl). The beam focused by the objective was several micrometers in diameter at the waist. The working distance of focusing is selected so that the beam waist could be freely moved in-depth of the cuvette. From the back side, the cuvette was illuminated by a LED so that the transmitted light would impinge the DCC1645C CMOS camera (Thorlabs) connected to a personal computer, and the image of the cuvette with the cells would be displayed on the monitor screen. A dichroic mirror located between the lens and the camera is needed to prevent the reflected laser radiation from entering the camera. A power meter located next to the dichroic mirror (not shown in Fig. 1) makes it possible to correlate the power of the beam and the corresponding forces of cells interaction. The sample cuvette was placed onto a three-dimensional object stage thus allowing for a change of the position of the trapping beam in three coordinates x, y, z. A simplified layout of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Simplified layout of the experimental setup. The beam from the Nd:YAG laser is fed to an optical microscope equipped with a 100 × water-immersion type objective with a numerical aperture NA = 1.0 and a working distance of 1mm. The sample solution consists of washed RBCs and single ECs at low concentration.

2.4. Cuvettes for laser tweezers

In the experiments, we used home-made cuvettes consisting of subject and cover glasses. Two layers of double-sided sticky tapes were placed onto the subject glass, forming a microchannel of 100μm height. A cover glass was placed on the top of the subject glass and sticky tapes. RBCs and ECs suspended in blood platelet poor plasma were administered into the cuvette immediately before measurements. In this case, single ECs settled on the bottom of the cuvettes and single RBCs could be trapped with LT and set in motion relative to ECs. The storing of the cells before the measurements lasting not longer than 1h and the measurements themselves lasting not longer than 30min each and not longer than 3h all together were carried out at room temperature.

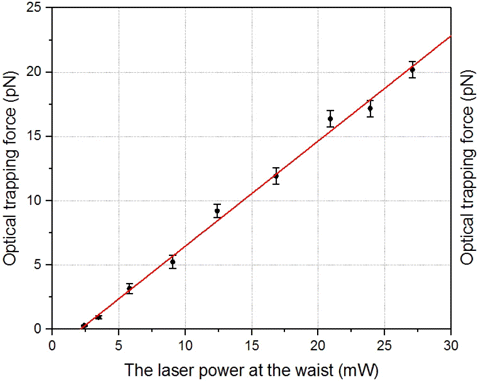

2.5. Laser tweezers calibration

LT calibration is necessary to relate the force of optical trapping an individual cell with LT and the power of the radiation incident onto the cell.28,29 The force of viscous friction (drag force) was used as a calibration force, which depends on the speed of cell movement in the liquid environment according to the Stokes law30 :

Here, η=1.7μPa⋅s — the dynamic viscosity of blood plasma, a — the characteristic size of the RBC (the size ranges 6–10μm), υ — the RBC speed of movement relative to stationary plasma in the cuvette, K — correction factor accounting for the nonsphericity of RBC, which is calculated using numerical simulation.31,32 The characteristic size of RBC is calculated from the image captured by the camera. For each given trapping beam power, the speed is determined, at which the RBC is pulled out of the trap by the drag force. Then, according to Stokes’s law, this force is calculated, which is assumed equal to the optical trapping force.

The correction factor K is calculated on the basis of the ellipsoidal shape of RBC and supposed that the major and minor axes of the ellipsoid, which mimics the cells shape are equal to a and b :

This calibration method is convenient because it is based on a linear relationship between the optical trapping force and the speed of movement of an RBC. To arrange the free movement the RBC at different speeds relative to the plasma, a system with a built-in stepping motor connected to the movable stage was used. In our experiments, the calibration was carried out each time before the experiment. A typical calibration curve is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Typical calibration curve for the LT.

2.6. Interaction force measurements

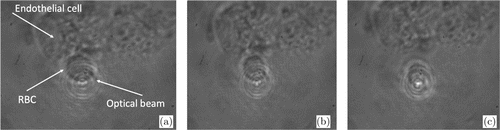

Measurements of the interaction forces between individual RBCs and individual ECs were carried out according to the following protocol: we searched visually for a single EC stuck to the bottom of the cuvette with a single RBC adherent to it. Then under minimal laser power we trapped this RBC with the laser beam and manipulated it aiming to tear it off from the EC. If the laser power was not sufficient to tear off the RBC, we gradually increased the laser beam power until the trapping force sufficed to disattach the cells. (Fig. 3). The value of this force was defined as the interaction force between the RBC and the EC. Within one experiment, this procedure was repeated with 10–12 pairs of cells. For more detailed information about a similar procedure of measuring the force of interaction between individual RBCs, please refer to an earlier work of our laboratory.2

Fig. 3. The stepwise procedure of measuring the interaction force between individual RBC and individual EC: (a) an RBC adherent to an EC is trapped with the laser beam; (b) the beam power is stepwisely increased and the RBC is manipulated but the trapping force does not suffice to tear the RBC off from the EC; (c) under certain beam power the trapping force is sufficient to tear the RBC off from the EC.

2.7. Reagent treatment

In order to test the hypothesis about the effect of fibrinogen on the adhesion of RBC to EC,33,34 we added human fibrinogen (Sigma, Life Science) to the platelet poor plasma solution with cells at the concentration varying in the range of 3–9mg/mL 5min before the measurements. It should be noticed that in human body the normal range of fibrinogen concentrations is from 2mg/mL to 4mg/mL. While in some diseases in particular at hyperfibrinogenia and COVID 19, this concentration can reach higher values up to 9mg/mL.35

The effect of dextran on the adhesion of RBC to EC was also investigated. We used dextran (Sigma, Life Science) with the molecular mass of 70–500kDa at the concentration of 20–60mg/mL. Before starting the measurements, the cells were incubated in platelet poor plasma at various dextran concentrations for 30min.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Measurements of the force of interaction of the cells for each sample were carried out with at least 10 pairs of different RBCs and ECs, and the results were averaged. In Figs. 4–10, the mean values of the measured parameters and standard deviations from the mean values are shown.

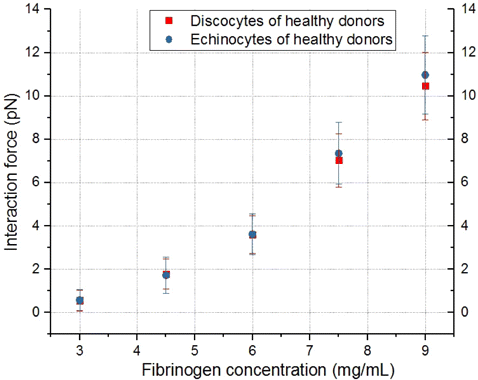

Fig. 4. Comparison of the dependencies of the interaction force between individual discocytes and echinocytes from the blood of healthy volunteer and ECs on the concentration of fibrinogen.

3. Results and Discussion

The application of LT made it possible to measure the interaction forces between individual RBCs and ECs (non-activated or pre-activated with TNF-α).

In our study, we have first compared the interaction forces measured between individual discocytes and echinocytes from the blood of healthy volunteer and ECs. We have found no statistically significant difference between discocytes and echinocytes. Only slight increase in the measured force value characteristic of echinocytes can be observed at high fibrinogen concentration value, see Fig. 4. However, in case of discocytes in blood of patients suffering from T2DM the force of the interaction of echinocytes was significantly higher.

This is why we used discocytes from the blood of healthy volunteers and echinocytes from the blood of patients suffering T2DM.

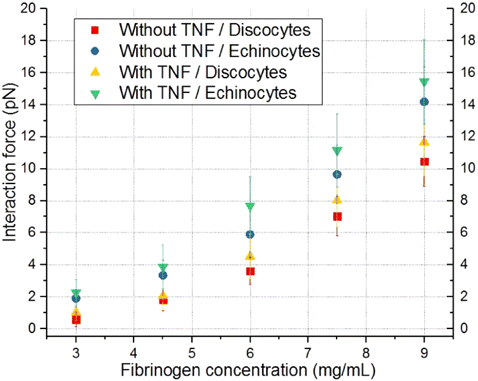

The results plotted in Fig. 5 show that an increase in the fibrinogen concentration enhances the adhesion of normal RBCs (discocytes) to nonactivated ECs in a nonlinear way. In case of ECs interaction with discocytes without preactivation, the interaction force at the maximum used concentration (9mg/mL) equaled to 10.5 ± 1.5 pN. Preactivation of ECs with TNF-α does not significantly affect the adhesion of RBCs: at the fibrinogen concentration of 9mg/mL, the interaction force was 11.7 ± 2.1 pN. The blood of diabetic patients was used in order to assess the effect of the shape of RBCs on the cells interaction strength. A significant amount of altered RBCs, echinocytes, was found in the T2DM patients’ blood. These cells were selected for the measurements, which showed that an increase in the fibrinogen concentration in the sample had a greater effect on the interaction force during the adhesion of echinocytes to ECs than discocytes. Thus, at the maximum used concentration of fibrinogen in the sample, the force of the interaction between echinocytes and ECs is 14.2 ± 2.2 pN, while in the case of discocytes it was 10.5 ± 1.5 pN as stated above. Preactivation of ECs results in the stimulation of the interaction of echinocytes and ECs but not statistically significant: compare 15.4 ± 2.6 pN for echinocytes with activated ECs and 14.2 ± 2.2 pN for echinocytes with nonactivated ECs. Thus, altered RBCs of diabetic donors have greater capacity of interaction with ECs.36,37,38 According to these results, we can presume that the blood cells of diabetic donors may have stronger interaction also with vascular endothelium of the blood vessels in vivo.

Fig. 5. Comparison of the dependencies of the interaction force between individual RBCs and ECs on the concentration of fibrinogen for cases without and with preactivation of ECs with TNF-α, as well as for different forms of RBCs (discocytes/echinocytes). Red squares indicate a case without preactivation and discocytes. The case without preactivation and echinocytes is indicated by the blue circles. Results obtained in the case of preactivation and echinocytes/discocytes are indicated by green/yellow triangles correspondingly. Each point on the graph corresponds to the average force of interaction of different individual RBCs with different individual ECs based on 10–12 measurements.

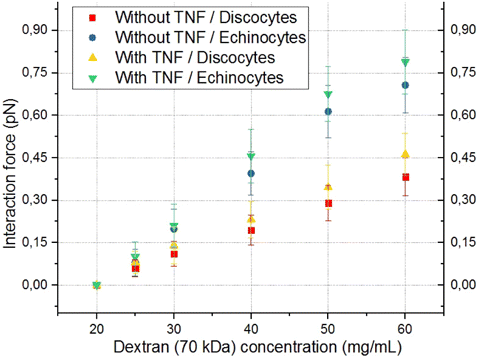

Fig. 6. Comparison of the dependencies of the interaction force between individual RBCs and ECs on the concentration of dextran with the molecular mass of 70kDa for cases without and with preactivation of ECs with TNF-α, as well as for different forms of RBCs (discocytes/echinocytes). Red squares indicate a case without preactivation discocytes. The case of preactivation and discocytes is indicated by yellow triangles. A case without preactivation and echinocytes is indicated by blue circles. Results obtained in the case of preactivation and echinocytes/discocytes are indicated by green/yellow triangles correspondingly. Each point on the graph corresponds to the average force of interaction of different individual RBCs with different individual ECs based on 10–12 measurements.

The next task was to assess how dextrans with a molecular mass of 70–500kDa affect the forces of interaction between individual RBCs and ECs.

In the case of adding the 70kDa dextran solution in concentration increasing from 20mg/mL to 60mg/mL to the suspension of echinocytes, their force of interaction with preactivated ECs increases almost linearly and amounts to a maximum of 0.8 ± 0.1 pN. At the low dextran concentrations of 70kDa, the interaction forces for different conditions are very small and close to zero. The difference between activated and non-activated ECs for echinocytes was 0.08 ± 0.06 pN. When comparing discocytes and echinocytes, the difference in interaction forces with preactivated ECs was 0.3 ± 0.09 pN.

The next task was to assess how the adhesion of individual RBCs to ECs depends on the molecular mass of dextran. For this purpose, we carried out the experiments with dextrans of molecular masses from 150 kDa to 500 kDa (Figs. 7–10).

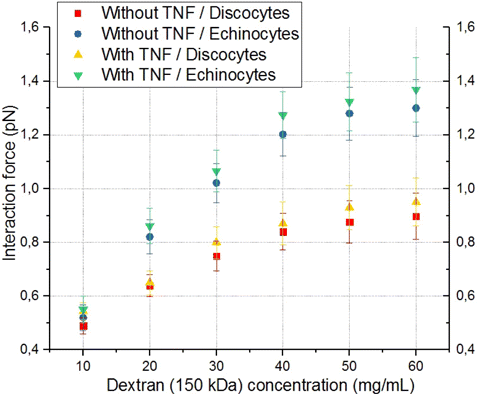

Fig. 7. Comparison of the dependencies of the interaction force between individual RBCs and ECs on concentration of dextran with the molecular mass of 150kDa for cases without and with preactivation of ECs with TNF-α, as well as for different forms of RBCs (discocytes/echinocytes). Red squares indicate a case without preactivation and discocytes. The case of preactivation and discocytes is indicated by yellow triangles. A case without preactivation and echinocytes is indicated by blue circles. Results obtained in the case of preactivation and echinocytes/discocytes are indicated by green/yellow triangles correspondingly. Each point on the graph corresponds to the average force of interaction of different individual RBCs with different individual ECs based on 10–12 measurements.

With the addition of 150kDa dextran, the interaction forces increase in comparison with 70kDa dextran (at the dextran concentration of 60mg/mL for echinocytes, the interaction force was 1.38 ± 0.12 pN). Similar to the situation with 70kDa dextran, the interaction forces are close to zero at low concentrations (at 10mg/mL, the interaction force was 0.55 ± 0.05 pN). The difference between activated and nonactivated ECs for echinocytes was 0.07 ± 0.1 pN. When comparing the cases of discocytes and echinocytes, the difference in interaction forces with preactivated ECs was equal to 0.4 ± 0.1 pN. For discocytes, a saturation dependence was observed at high dextran concentrations (Fig. 7).

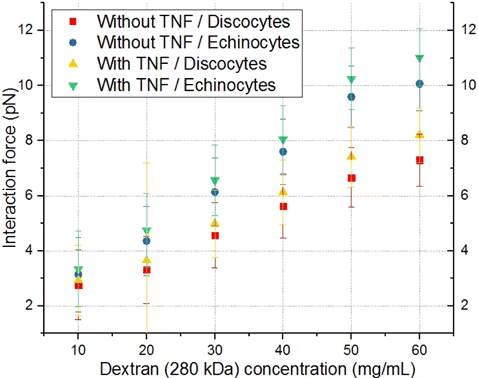

The force of cell interaction for 280kDa dextran increased with the growth of the dextran concentration and amounted to 11 ± 1 pN with activated EC and echinocytes (Fig. 8). The difference between activated and nonactivated ECs for echinocytes was 0.3 ± 0.1 pN. When comparing discocytes and echinocytes, the difference in interaction forces with activated EC was 3 ± 1 pN.

Fig. 8. Comparison of the dependencies of the interaction force between individual RBCs and ECs on concentration of dextran with the molecular mass of 280kDa for the cases without and with preactivation of ECs with TNF-α as well as for different forms of RBCs (discocytes/echinocytes). Red squares indicate a case without preactivation and discocytes. The case of preactivation and discocytes is indicated by yellow triangles. The case without preactivation and echinocytes is indicated by blue circles. Results obtained in the case of preactivation and echinocytes/discocytes are indicated by green/yellow triangles correspondingly. Each point on the graph corresponds to the average force of interaction of different individual RBCs with different individual ECs based on 10–12 measurements.

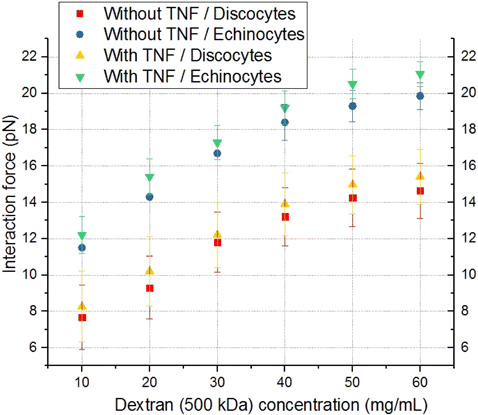

When 500kDa dextran was added to the plasma solution, the interaction force between RBCs and ECs turned out to be significantly higher than in the case of 70kDa dextran (at 9mg/mL, the interaction force was 21.0 ± 0.7 pN), which corresponds to the nonlinear nature of the force growth with increasing dextran concentration (Fig. 9). At the highest concentrations of 500kDa dextran, the available laser beam power was not sufficient to separate the adhered ECs and RBCs. The difference between activated and non-activated ECs for echinocytes was 1.2 ± 0.7 pN. When comparing discocytes and echinocytes, the difference in the interaction forces with activated ECs was 6.0 ± 1.5 pN. In this case, saturation was not observed, and a further increase in the dextran concentration was meaningless due to the excessive dose of the substance in the plasma.

Fig. 9. Comparison of the dependencies of the interaction force between RBCs and ECs on the concentration of dextran with the molecular mass of 500kDa for the cases without and with preactivation of ECs with TNF-α, as well as for different forms of RBCs (discocytes/echinocytes). Red squares indicate the case without preactivation and discocytes. The case of preactivation and discocytes is indicated by yellow triangles. The case without preactivation and echinocytes is indicated by blue circles. Results obtained in the case of preactivation and echinocytes/discocytes are indicated by green/yellow triangles correspondingly. Each point on the graph corresponds to the force of interaction of different individual RBCs with different individual ECs based on 10–12 measurements.

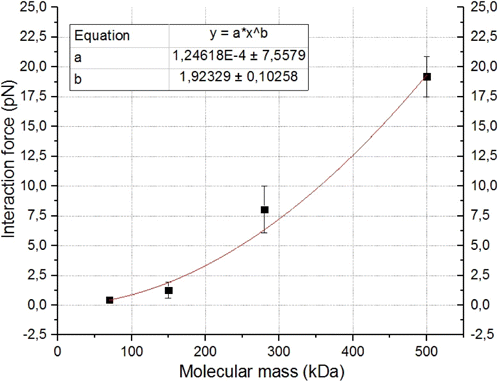

Based on the obtained data, Fig. 10 represents the dependence of the force of interaction between echinocytes and ECs on the molecular mass of dextran at its fixed concentration of 40mg/mL.

Fig. 10. Dependence of the force of interaction between echinocytes and preactivated ECs on the molecular mass of dextran at a fixed concentration of 40mg/mL. Each point on the graph corresponds to the force of interaction of different individual RBCs with different individual ECs based on 10–12 measurements.

The graph shows a nonlinear increase in the force of cell interaction along with the increase in the molecular mass of dextran. This indicates the effect of the molecular mass of dextran on the ability of the dextran molecule to adsorb on the cell membranes. In the first approximation, such a dependence can be approximated by a power function.

The alternative technique for measuring interaction forces between live cells is Atomic force microscopy (AFM). Thus, using the method the force of interaction between fibrinogen as the bringing molecules and RBC membrane was measured and found ranging from 20 pN to 130 pN.39,40 The same technique was used to measure the adhesion between two RBCs.41,42 It should be noted that this range of forces is beyond that obtained in our measurements.

The interaction of RBC and EC is mediated by a number of factors including von Willebrand factor and syalic group on the RBC membrane.43,44 However, we did not discuss them in our paper because we did not make measurements involving them.

A variety of other intercellular adhesion molecules are expressed on ECs, which, among other things, can bind both polysaccharide molecules (such as dextrans) and glycoproteins-like fibrinogen. Such molecules include, for example, the ICAM family of receptors,11 complexes CD147,45 integrin complexes IIbIIIa,46 and many others. It is also known that both dextran and fibrinogen are sorbed on RBCs.46,47 Since bridging is based on the adsorption of macromolecules on the surface, this mechanism cannot be ruled out. But the depleted layer also takes place.48 In the blood plasma, in addition to fibrinogen, there are many components that differ in structure and molecular weight (albumin, globulins). They are also able to influence the interaction of the cells with each other, despite the fact that the mechanisms of their specific binding to the membrane have not yet been fully investigated.49

4. Conclusion

Using LT, we measured the forces of the interaction between individual RBCs and individual ECs in the presence or absence of activator TNF-α, as well as for different shapes of RBCs (discocytes or echinocytes), and with the extra addition of proaggregant macromolecules (fibrinogen and dextran) to blood plasma. Our experiments showed that in all considered cases of ECs interaction with RBCs, the interaction force raises along with increasing concentration of fibrinogen and dextran. We showed that an increase in the fibrinogen concentration in plasma leads to a nonlinear increase in the force of interaction between RBCs and ECs. At low concentrations of fibrinogen, the forces of interaction are practically the same and the difference in the values of the forces increases with increasing concentration.

In experiments with dextran, a slight increase in the interaction forces is observed with the addition of dextran 70kDa. The situation changes dramatically when 500kDa dextran is used. In this case, the interaction forces significantly exceed those for dextran 70kDa and 150kDa at the same concentration. Alteration of the discoid RBCs shape leads to a higher interaction force. Preactivation of ECs with the TNF-α also results in an increase in their force of interaction with RBCs. The largest interaction forces are observed in the case of interaction of ECs preliminarily activated with TNF-α and echinocytes.

Our results give quantitative basis to the studies,50,51 in which the adhesion of echinocytes to ECs was experimentally observed. Also, our results quantitatively confirm the work,52 which showed that this interaction can be increased if ECs are activated with TNF-α.

Basing on the results obtained in our experiments, we can speculate about what the two investigated agents are doing to promote adhesion. With the dextrans, it looks like the observed adhesion might be a colloidal depletion interaction while with the fibrinogen the adhesion mechanisms might be a chemical bridging. Our further work will be aimed at the more detailed study of the interaction of various blood components with the EC monolayers under different ways of EC activation. These results could help us to better understand the process of interaction between RBCs and endothelium in vivo.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Local ethics committee of the Medical Scientific and Educational Center of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University. All blood donors gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Grant No. 19-52-51015). This research was performed according to the Development program of the Interdisciplinary Scientific and Educational School of Lomonosov Moscow State University “Photonic and quantum technologies. Digital medicine”. The authors are grateful to Dr. Ekaterina Kiseleva from the Koltsov Institute of Developmental Biology (RAS) for supplying us with ECs and Dr. Dmitry Nechipurenko from the Lomonosov Moscow State University for useful discussions.