Numerical model for evaluating the speckle activity and characteristics of bone tissue under the biospeckle laser system

Abstract

This paper discusses and studies the composition and characteristics of biospeckle on the surface of bone tissues. We used a laser speckle device to capture biospeckle patterns from fresh pig bone tissue. Traditional speckle activity metrics were used to measure the speckle activity of ex vivo bone tissue over time. Both Gaussian and Lorentzian correlation functions were used to characterize the ordered and disordered motion of the bone surface, together with volume scattering, to construct the model. Using the established mathematical model of the spatio-temporal evolution of the biospeckle pattern, it is possible to account for the presence of volume scattering from the biospeckle of bones, quantify the ordered or disordered motions in the biological speckle activity at the current time, and assess the ability of laser speckle correlation technique to determine biological activity.

1. Introduction

Bone grafting and transplantation are widely used in clinical practice. In clinical surgery of bone or prosthesis transplantation, bone healing has three mechanisms: Osteogenesis, osteoinduction, and bone conduction. Both osteogenesis and osteoinduction are related to osteoblast activity of the transplanted bone tissue.1,2 The early osteogenesis mediated by viable transplanted osteoblasts is very important for the formation of bone callus within 4–8 weeks after surgery.3,4 If the donator part doesn’t have enough functional osteoblasts during the surgery, then the osteogenesis process will be restricted, which may probably lead to the failure of transplanted surgery. Therefore, the time of bone tissue ex vivo will directly affect the activity of bone tissue and the success rate of surgery.3,5,6 When it comes to the clinical practice, there are so many factors that may affect the osteoblastic activity of the donator bone, including but not limited to the procedure of surgery, the age of patient and so on. However, unfortunately, surgeons have almost no means of determining osteogenic activity to guide their surgical strategies for now. Therefore, a sensor that can quantitatively assess the activity of bone tissue is greatly desired. In scientific research, it is now a common practice to obtain cells by digesting bone blocks at various time points in isolation and then performing live cell counts to analyze cell survival in relation to the time spent in isolation. However, this technique has a number of difficulties, including long incubation time and manual effort, and is not a suitable method for practical clinical use.4,5,6,7 For practical clinical applications, a noncontact and rapid method is required to provide quantitative information on the activity of the bone surface. In addition to histological cell culture methods, dynamic speckle measurement technique can also be used to determine cell viability. As the laser propagates through a strongly scattering medium such as bone tissue, it undergoes multiple scatterings, changing the original phase information and direction of propagation, destroying coherence, and eventually forming a scattering speckle.8,9,10 At the same time, the dynamic or physiological characteristics of the sample surface itself, such as its size change, shape change, microbial movement or composition change and other factors, change the height of the scattered wave front, as well as the phase of the scattered light, the scattered speckle will change and produce dynamic speckle with the orderly and disorderly movement in the tissue, so the scattered speckle pattern in the time domain contains information about the characteristics of the sample surface, forming dynamic speckle or biospeckle.11,12 This occurs with paint drying or metal corrosion13,14,15 and with biological samples, such as crops, tissue or bacteria and parasites.16,17,18,19 Using simple optical equipment and acquisition systems to record the intensity of scattered light and obtain a series of dynamic speckle patterns, it is possible to distinguish the differences among samples, which can be used to monitor bacterial activity in the medium or to monitor the effects of drugs on parasites.19,20,21

However, the activity of dynamic speckles is usually considered to be the result of numerous scattering wavelet dynamics, which involve many complex physical and physiological mechanisms.22,23 Such dynamic characteristics are usually very complicated. Therefore, many effective processing methods are needed to analyze the speckle activities to understand and evaluate the characteristics of the surface activity of the sample and to establish the relationship between the speckle sequence and the physiological characteristics of the sample. The situation is more complex on the bone surface, where three main factors can be involved:

| (i) | Water is a ubiquitous biological solution, including at the surface of bone tissue, which is involved in and regulates intermolecular forces, enzyme catalysis and molecular recognition in biological cells. The differences between cellular water and bulk water have therefore been extensively studied, characterized and understood. Cellular water is often considered to be more structured or ordered than bulk water, but this assumption is not easily verified, while kinetic effects of solutes in water may also be important. It can be concluded that the stability of bound water is enhanced relative to that of free water, and that the residence time (or shear viscosity coefficient) of bound water on bone surfaces is longer when brought about by biological water.24,25,26 | ||||

| (ii) | As the drying process proceeds ex vivo, this complex liquid film on the bone surface may break down, shrink, thicken or thin rapidly or slowly, which will interfere with our assessment of correct bone activity.27,28 | ||||

| (iii) | Finally, bone, as a saturated porous medium, is divided into a solid phase and a fluid phase (mainly water). It is now generally accepted that skeletons present three main levels of porosity.27,29 The large pores correspond to vascular systems (Havers and Volkmann tubes, typical diameters of 50μm). Mesoporosity corresponds to the formation of lacuno-canalicular pores containing an osteocytes’ network of stellar bones (100nm). The smallest porosity corresponds to the internal space of the collagen–apatite structure, which has a typical size of about 5nm. | ||||

These three different porosities, from the microscale to the nanoscale, provide different levels of fluid transport capacity and permeability to the bone tissue, allowing the biological environment of the bone surface to be influenced by this nanoscale fluid dynamics as well. At the same time, the continuous flow of bone fluids and their transport on the bone surface allows the fluid environment on the surface to be maintained for a long period of time,27,30,31 distinguishing it from nonphysiological materials. These factors make the collected biospeckle activity not just that of osteoblasts, but a collection of complex dynamic physiological behaviors of the surface.

In this paper, we explore and investigate the characteristics of biospeckle from ex vivo bone tissue and analyze the causes and sources of these characteristics, thus making biospeckle one of the possible techniques for evaluating osteogenic activity. We used a laser speckle device to capture biospeckle patterns from the fresh bone tissue. Traditional speckle activity metrics were used to measure the speckle activity of ex vivo bone tissue over time. Both Gaussian and Lorentzian correlation functions were used to characterize the ordered and disordered motion of the bone surface, together with volume scattering, to construct the model. The parameters of the model were set to match the characteristics of the actual bone tissue speckle pattern sequence taken. Using the established mathematical model of the spatio-temporal evolution of the biospeckle pattern, it is possible to quantify the ordered or disordered motions in the biological speckle activity at the current time and assess the ability of laser speckle correlation technique to determine the biological activity in the presence of biospeckle.

2. Experiment Preparation

2.1. Ex vivo

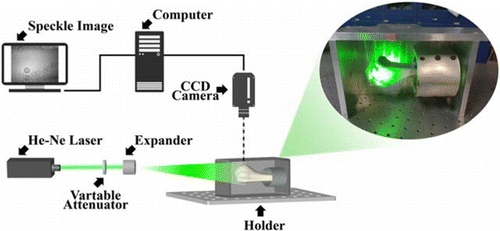

In order to collect the sample data, a digital speckle pattern acquisition system was established, as shown in Fig. 1. In the experiment, the model acA2440-20gm GigE digital camera (BASLER, Germany) was used. The photosensitive chip used by the camera was a Sony IMX 264 CMOS chip with target size of 2/3”. The lens (COMPUTAR, Japan) with a focal distance f of 25mm (Aperture Type: manual) was adopted as an imaging lens in this experiment. The single longitudinal mode HeNe laser with 532 nm wavelength was used as the light source. The speckle contrast was adjusted by the variable attenuator and then the beam was expanded by the beam expander to irradiate the sample.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the detection device.

During the acquisition of the dynamic speckle pattern sequence, the adjustable attenuator was adjusted to keep the average intensity in the image constant. To evaluate the dynamic change of speckle pattern over a period of time, in the acquisition process, we control the exposure time to 40ms, the acquisition rate was 23 fps of the camera, a total of 50 frames were collected to form a speckle image sequence.

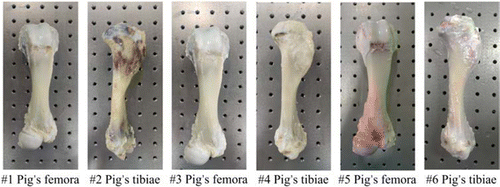

The active samples we selected for the ex vivo experiments were from experimental Bama minipigs, as shown in Fig. 2. Experiments were performed within 15 min after bone extraction, and samples #1–#6 were tested in air and clamped using a custom-made clamping device to ensure stability. One set of dynamic speckle sequences was measured every 0.2h (12min) for 12h, yielding a total of 50 image sequences.

Fig. 2. Pig bone specimens (numbers: #1–#6).

2.2. Biospeckle characterization

There are no classic standards to describe or evaluate biospeckle. Characterizing the activity level of biospeckle by a single plaque characteristic is one-sided, therefore we performed a multivariate evaluation. Biological speckle sequences recorded ex vivo from pig bone were quantified using parameters related to time history speckle pattern (THSP),32 grey level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM),33 including the moment of inertia (IM),34 correlation energy, and, homogeneity, which are widely used in the literature.

The speckle images are cascaded in the order of acquisition to form a cube and then sliced through the cube along the time axis to obtain an image called the THSP. The moment of inertia is derived from THSP and the characteristic value is characterizing the stability of THSP.

Similarly, three other statistics from the GLCM are often used to perform texture analysis of scattered images: Energy returns the sum of the squares of the GLCM pixel values and is equal to one for a constant image. Homogeneity returns a value that measures how close the distribution of elements in the GLCM is to the diagonal of the GLCM. Correlation is a measure of how pixels are related to their neighbors.

3. Simulated Biospeckle Comparison

To supplement the experimental measurements, researchers often turn to computer simulations of phenomena of interest. An important situation is the temporal decorrelation of speckle patterns. This behavior is of interest, for example, in the use of laser speckle dynamics to evaluate fluid flow, or in quasi-elastic light scattering to determine the molecular mass.35,36 However, the difficulty of this argument is that when there are multiple feature correlations, the actual de-correlation process is different from the simulated linearity. Many researchers only use the Lorentzian model to explain this relationship. In fact, Lorentzian is a uniformly widened line type that only applies to Brownian motion. In this case, the dynamics of the individual particles represent the whole. The other extreme is the nonuniform (Gaussian) distribution, which corresponds to a process whose dynamics are specific to a single scatterer.37,38 For complex motions, such as the surface motion of bone tissue, the correct model is undoubtedly between these two extremes.39,40,41 On the surface of bone tissue, there is a process of gasification of free water and bound water. At the same time, the disordered movement of water molecules, the rupture and contraction of surface biofilm and other factors constitute a disordered movement that represents different scales, and individual particles cannot represent the whole. Hidden within this is the orderly movement of osteoblasts.

A similar situation occurs in spectral line patterns in atmospheric physics, meteorology, cosmology, and other studies.42 Since the spectral line pattern contains information about the internal structure of the luminous particles, interparticle interactions, and the surrounding environment. In the case of low pressure, the spectral line spreading is dominated by Doppler spreading. While in the case of very high pressure, the luminescent particles and other particles frequently collide with collisional spreading generated by the dominance of the Lorentzian line shape function. In the actual light-emitting system, two types of broadening mechanism are present, the spectral line shape for the integrated broadening line pattern. At this time, the corresponding line function is the convolution form of Lorentzian line and Gaussian line function, called Voigt profile.

Note that in the above discussion, we have mentioned the convolution of two line shapes. Although it is obvious through the Wiener–Khinin theorem.43 that Gaussian and Lorentzian functions form Fourier transform pairs (as do Gaussian and Gaussian functions), it is often not realized that these “line spectra” are actually first-order probability density functions (PDFs) of the corresponding stochastic processes. Recall further that for the addition of statistically independent random variables, the probability density function of the sum is the convolution of the respective probability density functions. Thus, according to the convolution theorem, the net correlation function for combinatorial processes involving ordered and disordered motions is a simple product of the Gaussian correlation function and the Lorentzian (exponential) correlation function.44,45 In this paper, we unite Gaussian, Lorentzian, and volume scattering to obtain decorrelation time line shape close to real experiments by iteration, providing a convincing physical connection between the decorrelation process and the speckle activity.

3.1. Phase generation

Physically, coherent light scattering from a dynamic biological system over a period of time leads to temporal decorrelation of the speckle pattern in the viewing plane. In our simulations, the individual frames can be thought of as snapshots of the speckle field over time. Thus, in this case, the frame numbers can be considered as discrete time points.

In the literature,39 Duncan and Kirkpatrick illustrated the use of the concept of Copula to generate two representative functional forms for the decorrelation of the scattered sequences, the Gaussian function and the exponential function. However, this approach is not limited to such monotonically decreasing functions. In discussion, they point out that more complex dependencies can be generated by Copula. For example, for the case where there is both ordered and disordered motion of the scatterer. In this model, the phase change of the specified correlation function is included in the scattering matrix of each generated dynamic image to simulate the phase change of the biological scattering caused by the scattering center in the biological object. To better understand the generation of the correlated phases, we express the binary Gaussian array zk as a unit interval of the form :

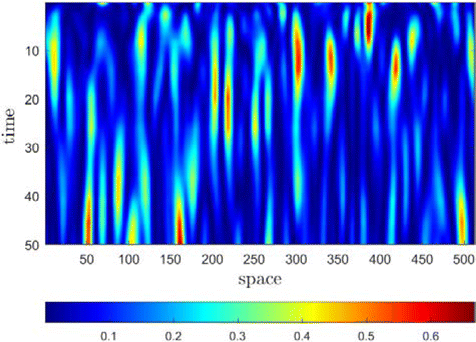

The correlation coefficient r between the current speckle pattern and the initial frame evolves from +1 to −1. For a specific correlation of r=1, the resulting phases are completely correlated, so the two speckle patterns are the same. When r=0, the phase is irrelevant, and the resulting speckle pattern is also irrelevant. What’s interesting is that for negative correlation, r<0, the phase appears as anti-correlation, but due to the complex symmetry of the Fourier transform, the resulting speckle pattern is irrelevant. Note that in the limit r=−1, the phase is completely anticorrelated, and the resulting speckle patterns are rotated 180∘ with each other. Moreover, Eq. (2) can also show that the algorithm produces a physically real and continuous phase trajectory between the two limits of r=1 and r=−1. As a result of this phase continuity, the evolution of the speckle pattern is also continuous (see Fig. 3), as one would expect from a real physical process. Therefore, this process is different from other simulation algorithms,46,47 which adds statistically independent phase increment at each step in the sequence, so the phase increment is discontinuous, and the evolution of the speckle pattern sequence is also discontinuous.

Fig. 3. A slice through the center row of the speckle cube indicates the temporal continuity of the speckle pattern sequence generated by the copula. The spatial dimension is along the horizontal axis and the time is along the vertical axis.

Here, it is clear that the initial and final values of zk are as follows :

As mentioned before, the correlation coefficient r will consist of a Voigt line shape with Gaussian and Lorentzian components, introducing σ and γ to represent the ratio of both of them48 :

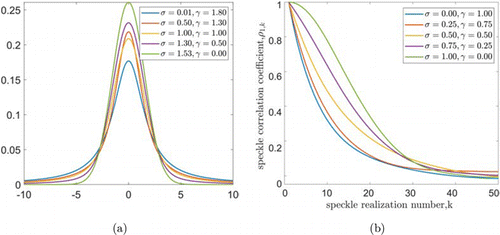

In Fig. 4, we show a typical Voigt function and a similar example of the correlation curves constructed according to the above formula. In the subsequent modeling process, the sum of both of them is transformed into the form of convolution.

Fig. 4. (a) For gaseous working substances, several typical line shapes of the Voigt line function consisting of Lorentzian and Gaussian line shapes. (b) Different scaled correlation curves according to Eqs. (1)–(4).

It should be noted that the above-mentioned phase generation does not assume other forms of speckle displacement. If the sample to be tested is not stable (or there is external interference), the correlation will be further reduced due to the speckle shift. On the other hand, the scattering that produces speckle can come from the surface of the biological sample, or from the inside of the volume.49 During the experiment, it was found that the decorrelation curve obtained by using only the ordered and disordered models still has a fixed offset from the data obtained from the actual bone sample. This is because the interaction between the laser and biological tissue is complicated. Light that penetrates a surface (such as bone tissue) is scattered by osteoblasts, water, and other tissues. When these scatterers relocate, the biological clusters they produce will also travel and shift in shape. The higher the mobility of these scatterers, the higher the expected biospeckle activity rate. Studies have shown that the penetration depth of the laser in the tissue is 1–2mm, suggesting that the laser can penetrate beyond the surface.50 Each layer of tissue the laser passes through is expected to contribute to the integral activity of the biological sample. In the case of volume scattering, there is also a surface scattering component. The speckle pattern of the light penetrating material is composed of speckles of different sizes: (i) Large speckles generated by light scattered from the surface and (ii) smaller speckles generated by light emitted from the internal volume of the material. At the same time, in the case of a living body where the surface of the bone is the laser target, the laser is expected to be scattered by the tissue multiple times. The speckle metrology theory of volume scattering speckle lags behind that of surface speckle and the effect of volume scattering on the speckle correlation is still unclear.

3.2. Biospeckle simulation

In order to simulate the biological speckle pattern seen in the ex vivo sample, a numerical model was established in MATLAB. Physically speaking, coherent light scattering from a dynamic biological system over a period of time will cause the temporal decorrelation of the speckle pattern in the observation plane. In our simulation, each frame can be regarded as a snapshot of the speckle field over time. Therefore, in this case, the frame number can be regarded as a discrete point in time.

Here, we use the following method to generate a spatially band-limited speckle pattern: translate the pupil by a random series.39,51 A circular region of diameter d filled by into a square array of L×L is filled with complex numbers of unit amplitude, and the phase is uniformly distributed between (0,2π) as shown in Fig. 5. The ratio of L to D, meanwhile, represents the minimum size σ of the speckle, σ=L∕D. The Zk(xy) matrix representing the amplitudes of the complex speckle is created to represent the surface speckle, and has a larger input speckle size, σs=2 pixels. The matrix Vk(xy), which also represents the magnitude of the complex speckle, is made to represent volume scattering, and is given a smaller input speckle size, σv=0.8 pixels. These speckle size values are selected based on experience so that the size of the final simulated biological pattern matches the speckle size seen in the living bone tissue.

Fig. 5. Illustration of speckle pattern generation algorithm. The circular shaded area is filled with complex numbers of unit amplitude and phase uniformly distributed on (0,2π).

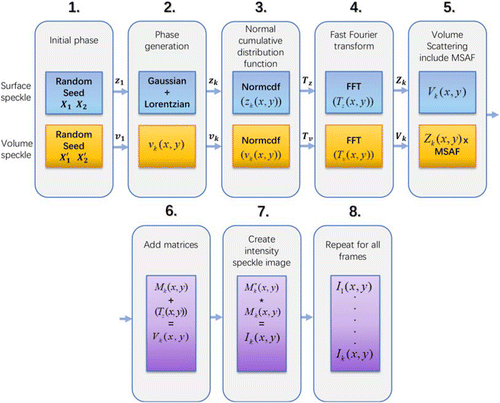

Mathematical dynamic speckle was generated by adopting speckle simulation methods described by Goodman49 and Duncan and Kirkpatrick.39,51 The procedure that was utilized to model biospeckle is presented in Fig. 6 and summarized as follows:

| (1) | For the first frame of speckle image (k=1), according to Eq. (1), X1 and X2 are two statistically independent random variables that obey a uniform distribution in the unit interval. X1 and X2 can be generated by setting two different seeds for the random number generator. This makes each simulation not fixed and random. After the amplitude and initial phase are generated, three types of phases are defined according to the phase generation method mentioned earlier. In this study, the size of X1 and X2 is set to be 512×512 pixels, and N is 50. | ||||

| (2) | According to Eqs. (2) and (3), in order to generate zk(x,y), the phase ϕk is generated by the de-correlation coefficient r, which is a combination of the proportional coefficients of both σ and γ (Gaussian and Lorentzian). | ||||

| (3) | Then, by performing percentile transformation on the z value, a statistically relevant frame uniformly distributed TZ value in the unit interval is obtained : TZ(k)=FZ[z(k)],(5) | ||||

| (4) | Subsequently, by introducing the multiplication factor m to adjust the decorrelation time, Zk(x,y) of complex amplitude speckles is obtained by performing fast Fourier transform on the both exp[i2πmTZ] and exp[i2πTv]. | ||||

| (5) | In order to consider the volume scattering effect of the sample, the Vk(x,y) matrix is multiplied by the multiple scattering amplitude factor (MSAF).52 MSAF is a measure of the relative amplitude of the scattered surface and volume components. Here, the value of MSAF is iterated between 0 and 1, and the value selected is to minimize the error between the model and the actual decorrelation curve. | ||||

| (6) | The two matrices were added together on a complex basis, resulting in the matrix Mk(x,y) | ||||

| (7) | The matrix Mk(x,y) was multiplied by its complex conjugate Mk(x,y), which is taken to create the first biospeckle intensity image frame. | ||||

| (8) | This procedure was continued until the required number of image frames N was built. | ||||

Fig. 6. Speckle simulation process.

In order to simulate the biospeckle pattern similar to the active pig bone samples, first, the multiplication factor m is adjusted to change the decorrelation rate, similar with the literature,15 the number of frames required to decrease the correlation of the speckle sequence from 1 to 1∕e is defined as the decorrelation rate RD. Furthermore, the maximum value of the de-correlation coefficient r is obviously one, so the sum of the coefficients σ and γ that determine the de-correlation line type is also one, which can be obtained by the following expression: r=σrG+(1−σ)rL. By choosing a coefficient iteration to minimize the linear error between the two, the difference between the simulation result and the actual result remains essentially constant. Finally, by iterating MSAF, the two decorrelation lines are the closest.

4. Results and Discussion

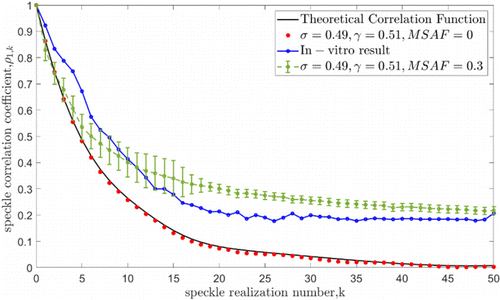

4.1. Model error analysis

The model for ex vivo bone speckle images outlined in Sec. 3.2 was used, and after determining the relevant parameters mentioned therein, we performed an error analysis between the simulated dynamic speckle generated by the model and the actual results collected from the bone. Due to the random nature of the initial seeds, different initial seeds were used to achieve 50 repeated simulations. A comparison of the decorrelation curves between the model and the speckle images of sample #1 collected 10min after being separated from the body (t=0) in Fig. 7, where σ equals 0.49 and γ equals 0.51. The ideal decorrelation curve without the volume scattering factor is considered according to Eqs. (1)–(4). It can be seen from Fig. 7 that, without considering the MSAF factor, the distribution between the continuous decorrelation curve of the input model and the discrete decorrelation curve of the model output is almost identical, with a standard deviation of σ=2.3% for the difference between them.

Fig. 7. Speckle correlation coefficient with sequence number. The black solid line and the red dot are the theoretical correlation coefficient curve and the point set calculated from the simulated speckle pattern when the volume scattering is not considered. The blue curve is the data from the ex vivo sample #1 at t = 0. The green curve is the best simulation result considering volume scattering, where MASF = 0.30 (since multiple random initial values existed, we give the curve of the average value).

It can also be noted that the trends of the simulations between considering the volume scattering and without the volume scattering are essentially similar, but there is still a fixed offset present. It is clear that the model with the volume scattering present is closer to the actual sample and the difference is smaller. The correlation of the simulation results drops relatively slowly after the amplitude reaches 1∕e, and stabilizes at 0.2–0.3, which is inherently different from the simulation results without considering volume scattering. It is probably due to the fact that the activity of the small speckles produced by the laser entering the interior of the material remains relatively stable. This random effect allows the entire sample to maintain this inherent correlation at a later stage and does not approach to zero as in the theoretical decorrelation process.

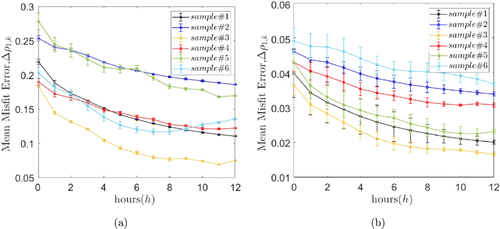

Figure 8 shows the error between the decorrelation line of the speckle images collected at different times and the model fitting for four samples from 0 to 12h. In order to present the data more clearly, the error bars, except for the first time point, are the average of the errors of all the collection moments within 1h. It can be seen that the error between the simulation results and the four samples gradually decreases with time. This is because volume scatter is the main factor that brings errors, and the impact of volume scattering is further reduced over time, which we will present more clearly in the subsequent presentation of the results. From the comparison of Figs. 8(a) and 8(b), since the model containing volume scattering will have more random initial quantities, it can be seen that the random fluctuations in Fig. 8(b) are larger, resulting in larger error bars. The fitting errors in considering volume scattering are also much lower, about an order of magnitude lower, than without volume scatter, which illustrates the presence of volume scattering in the speckle pattern of the actual bone tissue sample from a numerical fitting perspective.

Fig. 8. The speckle correlation coefficient error between the simulation result and the sample result. (a) Model error without volume scattering and (b) Model error considering volume scattering.

4.2. Feature comparison

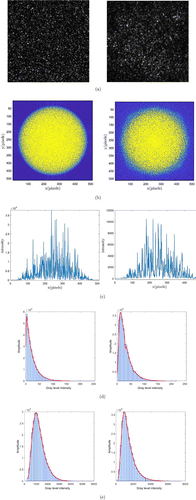

The comparison of the features shows whether the simulation results are consistent with the biospeckle sequence characteristics of the actual samples, so as to assess the validity of the simulation results. The first comparison is between the speckle size. The speckle size in the pattern from the actual sample of the isolated bone was calculated from the full-width at half maximum to 1 pixel. When the surface speckle size is 2 pixels and the volume scattering size is 0.8 pixels, the simulated biological speckle image obtains close results. Figure 9(a) visually shows the difference in speckle size between the simulated pattern and the actual sample. While the power spectral density (PSD) image more intuitively illustrates this situation, as shown in Fig. 9(b). It can be found that the diameter of the outermost circle of the PSD image is approximate, which reveals that the speckle size is close from a statistical point of view.

Fig. 9. The left figure shows the simulation data and its results, and the right figure shows the actual sample data and its results. (a) Speckle pattern, (b) corresponding PSD diagram, (c) intensity slice through the center of (b), (d) histogram created from single image, and (e) histogram created by all image sequence.

Then, we further explore whether the model-generated speckle patterns matched the actual first-order statistics, the histogram of the speckle image intensity between the actual image and the simulated image is evaluated. Figures 9(d) and 9(e) show the first image in the sequence and the overall grey scale histogram in all sequence, respectively, as a comparison. At this point, as another corroboration, it can be noted from both show comparable histogram characteristics in the distribution, shape or inclination whether in single image or the overall sequence. The standard deviations after scaling of their histogram lines are σ=8.7% and 3.9% respectively, neither exceeding the random error of a single measurement.

Further, Table 1 shows the quantitative results of the second-order statistics calculated from the GLCM of the THSP images between the isolated samples and a series of simulated biospeckle patterns with different activity, which also exhibit similar characteristics and tolerable deviations. We also introduce the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), which expresses the relationship between the maximum signal and the background noise, as a full-reference image quality evaluation metric for comparison between simulated and actual results.

| 1–12h ex vivo sample#1–#6 averaged results | Deviation of simulation | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | results | |

| PSNR (dB) | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.49 | ±0.07 |

| IM | 203.80 | 223.89 | 219.56 | 204.57 | 183.03 | 174.6 | 139.73 | 131.29 | 113.76 | 79.35 | 62.45 | 55.71 | ±34.12 |

| Correlation | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.87 | ±0.18 |

| Energy | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.007 | ±0.002 |

| Homogeneity | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.47 | ±0.05 |

4.3. Relevant results

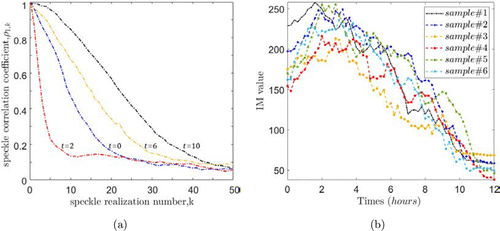

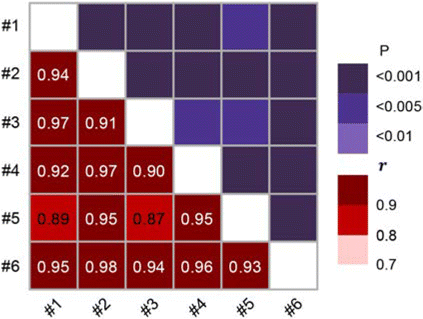

From the speckle image of the ex vivo sample, we obtained the correlation curve of the speckle sequence collected at different times (Fig. 10(a)) and the value of IM from the THSP image over time (Fig. 10(b)). An interesting conclusion can be observed from the figure: Obviously, after the bone is ex vivo, the cell activity on the surface is maintained or decreased over time and at a slow rate, and there is no possibility of cell proliferation. However, the opposite conclusion can be drawn from the speckle activity on the bone surface. It can be observed from Fig. 10(b) that at this time, the IM value, as a characteristic index of the speckle activity on the bone surface, shows a trend of first rising and then falling, reaching the highest value of activity in about 3h. A similar reversal of the speckle correlation coefficient can also be obtained in Fig. 10(a). By means and variances of the samples’ IM value, we scale the curves so that the activity factor obtained under the different samples are unified in the same range for examination, so as to pay attention to the trend of the biospeckle activity over time. The Pearson correlation coefficient r was obtained by correlation analysis53,54 and the results are shown in Fig. 11. It can be seen that from a limited number of six samples, this trend showed significant positive correlation.

Fig. 10. (a) Decorrelation results from sample#1 at four different times. (b) The line chart of samples’ the moment of inertia value over time.

Fig. 11. Correlation among trend data of different samples activity indexes in Fig. 10(b). Significance was shown in the top right. The hypothetical correlations are indicated in the lower left.

This is because the activity of biological speckle is an overall collection of complex dynamic physiological behaviors of the tested surface. Obviously, the active motion of a part of the measured surface is not monotonous at the beginning. As said in the introduction, this may be attributed to the increased activity of the biological water or water film on the surface of the tissue at the early stage of ex vivo. At the same time, the time scale of this process is lengthened due to the fluid transportation of different scale channels in bone tissue. Combined with the actual activity of bone cells on the surface and the internal volume scattering, as a collection of these complex activities, the curve as shown in Fig. 10(b) is formed.

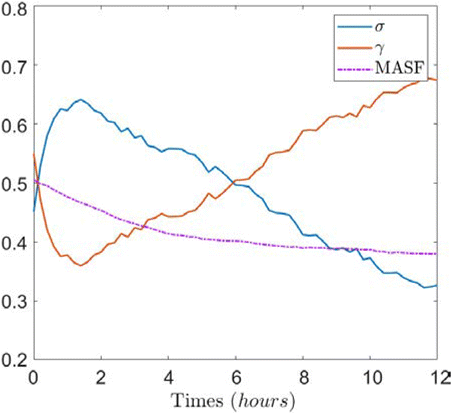

Furthermore, with the change of the index factors σ and γ of ordered and disordered motion obtained by model fitting and the curves of volume scattering coefficient MSAF, this viewpoint is further proved. As shown in Fig. 12, the ordered multiplication factor σ shows the same trend of speckle activity index but the gradient of change is slightly different. The γ value and MSAF show opposite trends, representing the disordered movement and volume scattering, respectively.

Fig. 12. Plot of scale factor σ, γ and MSAF against time of sample#1.

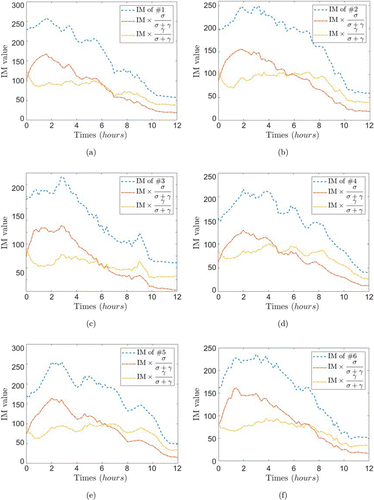

Finally, as an obvious promotion, we present the results with σ and γ as a scale coefficients of speckle activity indicators, combining IM value, as shown in Fig. 13. Obviously, this generalization can identify the impact of disordered activity to some extent and isolate the interference covariate. Unfortunately, as the volume scattering controlled by the MSAF factor is apportioned between the two coefficients when doing the complex conjugate operation, the simple proportional product does not provide a way to separate the effect of volume scattering on the samples, and therefore does not give a pure activity factor for the osteoblasts and makes further statistical analysis lacking in practical significance. Clearly there may also be a combination of the two activity models for the volume scattering (it is reasonable to assume that the proportion of activity in this component should be extremely small), which also remains to be explored further.

Fig. 13. Diagram of the variation of the moment of inertia of a sample with time and its variation when corresponding to different scale factors. (a) Sample#1, (b) sample#2, (c) sample#3, (d) sample#4, (e) sample#5, and (f) sample#6.

The simulated biospeckle in this paper is essentially a first-order empirical model. This model does not attempt to present a complete theoretical model, but is based on the matching of the temporal and spatial features of the simulated speckle with the corresponding features extracted from in actual sample. One limitation of this model is that it assumes that the speckle scattered from the sample surface and volume maintains the same linear polarization of the incident light. In practice, it is expected that the volume scattering component will exhibit depolarization. However, the model also captures the interesting results of the interference between volume and surface components, and the model with volume scattering makes the simulation results more realistic. Another limitation of this paper is that it is based on a small sample (n = 6). In addition, as an empirical model, model parameters are matched according to the results of the particular optical set-up used. Under different wavelength, the optical configuration used may need to be adjusted based on the first-order and second-order statistical characteristics of the actual speckle sequence. In order to fully simulate the patterns from bone tissue, it is necessary to deeply understand the scattering characteristics of bone surface and the temporal changes of these characteristics. At the same time, we also need to have a more accurate understanding of the physical process and statistics in the interaction between physiological materials and laser on complex surfaces. With a more comprehensive understanding of these features, other quantities such as surface roughness of tissue or rate of dehumidification process can be included in the mathematical model.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this work is to (1) evaluate the characteristics of biospeckle from ex vivo bone tissue and (2) analyze the causes and sources of these characteristics, so that biospeckle becomes one of the possible techniques for evaluating osteogenic activity.

This paper proposes and analyzes a mathematical model that uses Gaussian and Lorentzian correlation functions to describe the ordered and disordered motion of the bone surface, and combines volume scattering to describe the biospeckle captured from the sample. The model was well matched both qualitatively and quantitatively to the biospeckle patterns observed in specimens. In this model, we found that there was a volume scattering effect in the bone tissue and that the effect from volume scattering gradually decreases over time. In addition, the combination of multiple complex dynamic physiological behaviors on the surface of the bone tissue resulted in conventional indicators of speckle activity that did not follow the same trend as osteogenic activity, but instead showed a maximum of 2–4h after ex vivo, producing a standing point. The variation of the Gaussian and Lorentzian scaling factors in the model explains this phenomenon and isolates the traditional speckle activity index, which is expected to be a biological speckle index for assessing the osteogenic activity, though the quantitative scaling relationship between the two needs further experimental studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51975116), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (21ZR1402900) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and Graduate Student Innovation Fund of Donghua University (CUSF-DH-D-2021057).