Cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers in the diagnostic assays of Alzheimer’s disease

Abstract

The anti-amyloid-β (anti-Aβ) fibrils and soluble oligomers antibody aducanumab were approved to effectively slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) at higher doses in 2019, reaffirming the therapeutic effects of targeting the core pathology of AD. A timely and accurate diagnosis in the prodromal or pre-dementia stage of AD is essential for patient recruitment, stratification, and monitoring of treatment effects. AD core biomarkers amyloid-β (Aβ1−42), total tau (t-tau), and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) have been clinically validated to reflect AD-type pathological changes through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) measurement or positron-emission tomography (PET) and found to have high diagnostic performance for AD identification in the stage of mild cognitive impairment. The development of ultrasensitive immunoassay technology enables AD pathological proteins such as tau and neurofilament light (NFL) to be measured in blood samples. However, combined biomarker detection or targeting multiple biomarkers in immunoassays will increase detection sensitivity and specificity and improve diagnostic accuracy. This review summarizes and analyzes the performance of current detection methods for early diagnosis of AD, and provides a concept of detection method based on multiple biomarkers instead of a single target, which may become a potential tool for early diagnosis of AD in the future.

Abbreviations

| AD | : | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Aβ | : | Amyloid-β |

| T-tau | : | Total tau |

| P-tau | : | Phosphorylated tau |

| CSF | : | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| NFL | : | Neurofilament light |

| APP | : | Amyloid precursor protein |

| ELISA | : | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| BBB | : | Blood–brain barrier |

| PET | : | Positron-emission tomography |

| MRI | : | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| SPECT | : | Single-photon-emission computed tomography |

| SiMoA | : | Single-molecule array |

| CNT | : | Carbon nanotube |

| CJD | : | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| BACE1 | : | The β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 |

| VLP-1 | : | Visinin-like protein 1 |

| VAD | : | Vascular dementia |

| miRNA | : | Micro-RNA |

| exRNAs | : | Extracellular RNAs |

| BsAbs | : | Bispecific antibodies |

| MtAs | : | Multi-targeted antibodies |

| EAD | : | Early-onset AD |

| LAD | : | Late-onset AD |

| FTD | : | Frontotemporal dementia |

| HC | : | Healthy controls |

| MCI | : | Mild cognitive impairment |

| NAD | : | Non-AD dementia |

| NA | : | Not available |

| OD | : | Other dementias |

| OND | : | Other neurologic disorders |

| PAD | : | Probable AD |

| pMCI | : | Progressive MCI |

| SMC | : | Subjective memory complaints |

| sMCI | : | Stable MCI |

| pMCl | : | progressive MCI |

| CVD | : | Cardiovascular disease |

| Aβ42xMAP | : | Aβ42 quantified with xMAP technology |

| Aβ42MSD | : | Aβ42 quantified with MSD technology |

| ALS | : | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| SVD | : | Subcortical vascular dementia |

1. Introduction

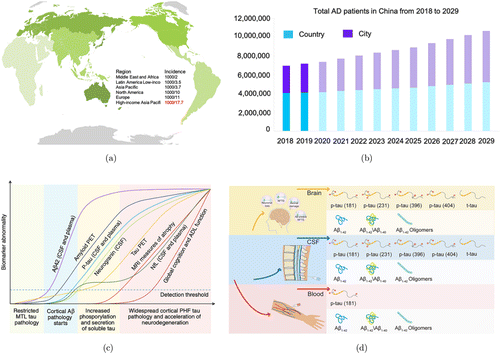

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder that may start 20–30 years before the clinical onset of the disease, which is accompanied by progressive neuropathology, brain atrophy, and ultimately cognitive decline.1,2,3 Unfortunately, with the increasing global population aging, the number of AD patients worldwide has a sharp increasing, of which the high-income Asia Pacific are more serious (Fig. 1(a)). The number of people with AD will have a steep increase from the currently estimated 7.5 million to over 10 million by 2029 in China (Fig. 1(b)).4 The cost of long-term care for those with AD is enormous, which not only brings a heavy financial burden on individuals and families but also has an inestimable impact on the Chinese national health system. There is currently a lack of treatment strategies for AD, and all treatments are limited to moderate relief of symptoms.5,6 Thus, it is critical to find new effective therapies for AD to slow its progression and prevent it from developing.

Fig. 1. (a) The global incidence of AD is most severe in the high-income Asia-Pacific region. (b) The total number of AD patients in China from 2018 to 2029 has a 10-year compounded growth rate of 4%. This growth is particularly significant among the Chinese urban population, with a 10-year compounded growth rate of 6%. (c) The trajectories of different fluids and imaging biomarkers in the AD continuum are depicted. Adapted from Ref. 228. (d) Representative AD core biomarkers in the brain, plasma, and CSF for brain imaging and fluid biomarkers-based detection.

In 1906, Alois Alzheimer first described the neuropathological features of AD as “miliary bodies” (amyloid plaques) and “dense fiber bundles” (neurofibrillary tangles).7 In the 1980s, Masters et al. successfully purified amyloid plaque cores and identified 4-kDa amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides as the main component of extracellular deposits.8 Grundke-Iqbal et al. found that neurofibrillary tangles consist of abnormally hyperphosphorylated forms of tau protein.9 Thus, amyloid plaques and tau protein are the primary biomarkers of AD, providing opportunities for the early diagnosis of AD. In the past few decades, the total-tau (t-tau), phosphorylated tau (p-tau) at different epitopes (e.g., threonine 231, serine 396, serine 404, and threonine 181), the 42 amino acid forms of β-amyloid (Aβ1−42),10,11 Aβ1−42/Aβ1−40 ratio,12,13,14 and Aβ protofibril15,16,17 had been validated to be related with neuropathologic changes in the brain (Fig. 1(c)). Biomarkers that reflect the pathological changes of AD in the brain are essential for clinical diagnosis, predicting progression, and monitoring drug efficacy in clinical trials. Prompt diagnosis in the prodromal AD or mild AD stage may improve patients’ access to healthcare and promote early and personalized interventions.

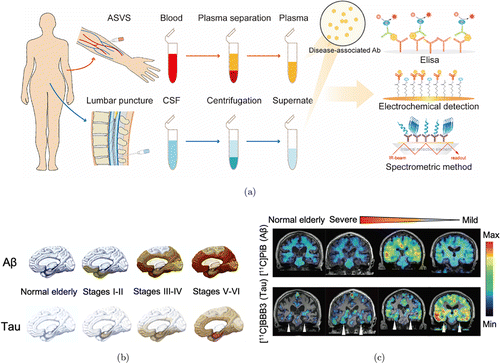

The ideal biomarker for AD before death should diagnose AD with high sensitivity and specificity, as confirmed by the gold standard of autopsy.18 Biomarkers for AD diagnosis include Aβ and tau positron-emission tomography (PET), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or blood measures to confirm the presence of AD pathological changes, including synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration, tau phosphorylation with neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) formation, and Aβ plaques deposition (Fig. 1(d)). Imaging biomarkers can be used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure brain volume and neuronal connections, and Aβ and tau PET can be used to detect the number of pathological protein deposits in the brain (Figs. 2(b) and 2(c)).19 Although MRI and PET imaging biomarkers with the reliability of accurately diagnosing brain diseases are approved for clinical use, the economic burden of imaging methods hinders their widespread application in identifying AD.20 Compared with MRI and PET imaging, CSF and blood tests are more affordable and easier to obtain.

Fig. 2. (a) Schematic illustration of the principal usage of AD core biomarkers for diagnosis in CSF or blood measurement, including ELISA, electrochemical detection, and spectrometric detection. (b) The schematic diagram shows the stages of Aβ (up) and tau (down) deposition in the human brain. Adapted from Ref. 124. (c) Representative clinical PET imaging of tau and Aβ accumulation showing the regional brain distribution of [11C]PBB3 and 11C-PiB in the normal elderly controls and patients with different disease states from severe to mild. Adapted from Ref. 229.

CSF biomarkers and plasma neurofilament light (NFL) also have excellent diagnostic performance for the detection of AD.21 The diagnosis of early-onset AD relies on the detection of AD-related biomarkers, but routine screening tools for AD are elusive. The most commonly used method to measure AD biomarkers is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), including assays for t-tau, p-tau, and Aβ1−42 (Fig. 2(a)).10,11 Clinical studies have always found a significant increase in t-tau and p-tau in AD, as well as a decrease in CSF Aβ1−42. These core AD CSF biomarkers have fully validated high AD diagnostic performance, consistent with autopsy diagnosis. The amyloid oligomer hypothesis is further supported by the use of a high-dose monoclonal antibody (mAb), aducanumab, to effectively slow down the progression of AD. Aducanumab selectively targets soluble Aβ aggregates (oligomers or protofibrils).22 Currently, the available AD laboratory biomarkers are mainly based on CSF analysis, whereas the highly invasive lumbar punctures limit their potential for serial measurement. Blood-based laboratory biomarker assays allow early identification of potential AD cases.

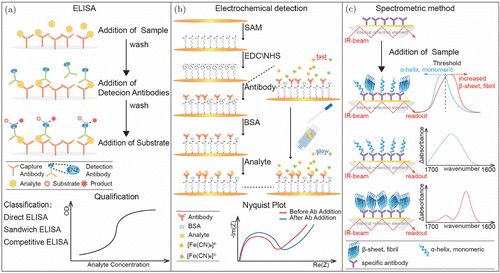

The measurement of brain-derived proteins that reflect neuropathological changes in the blood needs to overcome the measurement limitation of their low concentration, which is usually lower than the detection limit of standard ELISA and other detection methods. Recently, the use of novel ultrasensitive assay techniques, such as improved ELISA, electrochemical detection, or spectroscopy method, allows us to measure such proteins in the blood (Fig. 3). However, the heterogeneity of delayed AD pathology requires multiple biomarkers to reflect various aspects of AD pathophysiology. The current diagnostic analysis mainly depends on single biomarker immunoassay-based tools in CSF or blood measurement, resulting in variation in data detected by different laboratories. This review summarizes and analyzes the performance of current detection methods for early diagnosis of AD, and provides a novel concept of detection method based on multiple biomarkers instead of a single target, which may become a potential tool for early diagnosis of AD in the future.

Fig. 3. Schematic diagrams of the representative diagnosis tools. (a) Double-Antibody Sandwich ELISA (DAS-ELISA) for detecting AD biomarkers based on a pair of antibodies recognizing different antigenic determinants on the surface of biomarkers. (b) A sensitive interdigitated chain-shaped electrode sensor being developed for Aβ1−42 in human serum. (c) The immuno-infrared sensor that is used for the detection of β-sheet Aβ or tau secondary structure distribution in CSF and plasma. Adapted from Ref. 66.

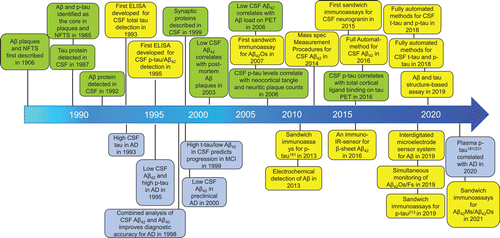

Fig. 4. Timeline for the evolution of the core biomarkers of AD in cerebrospinal fluid and blood. Green boxes represent pathophysiological findings; yellow boxes represent technical detection developments; and purple boxes represent clinical findings in exploring the AD biomarkers.

2. Current Fluid Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease

2.1. Basic biomarkers

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is formed by the limited permeability of the capillaries in the brain to keep the neuron microenvironment in a controllable state.11 The integrity of BBB reflects the health of the brain. The primary biomarkers are mainly composed of biochemical molecules in the BBB status and the inflammatory processes in the brain. The standard biomarker for BBB function depends on the ratio of CSF to serum albumin.23 Infections from neuroborreliosis, Guillain–Barré syndrome, brain tumors, and cerebrovascular disease (details are shown in Table 1) may cause an increase in the ratio of CSF to serum albumin, indicating that BBB is damaged. Generally, it is more common for patients with cerebrovascular disease to increase the ratio, but for patients with simple AD, the ratio is normal. A significant difference in the ratio of CSF to serum albumin could effectively distinguish other brain injuries from AD patients.23 Besides, the intrathecal immunoglobulin (Ig) produced in chronic inflammatory or infectious diseases of the central nervous system has no or very slight signs in most AD patients (Table 1). Thus, the detection of intrathecal Ig allows excluding chronic inflammatory and infectious disorders in the clinical diagnosis of AD.

| Biomarkers | Pathogenic process | Measure(s) | Changes in biomarker level in AD | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic biomarkers | ||||

| CSF cell count | Inflammation | CSF | Unchanged | Ref. 172 |

| CSF:serum albumin ratio | BBB function | Blood, CSF | Unchanged in the cases of pure AD, increase in mild-to-moderate AD | Ref. 173 |

| IgG or IgM index; IgG or IgM | Intrathecal immunoglobulin production | Blood | Unchanged | Ref. 174 |

| Core biomarkers | ||||

| t-tau | Neurofibrillary tangles | CSF | Marked increase in AD and prodromal AD | Refs. 10,11,134, and 175 |

| Aβ1−42 | Major component of senile plaques | Blood, CSF | Marked reduction in AD and prodromal AD | Refs. 25,132,133,176, and 177 |

| p-tau | Precedes formation of neurofibrillary tangles | Blood, CSF | Marked increase in AD and prodromal AD | Refs. 133–135 |

| Novel biomarkers | ||||

| BACE1 | Aβ metabolism | Blood, CSF | Marked increase in AD | Refs. 33,107,178, and 179 |

| Aβ1−38 | Amyloidogenic pathway of APP metabolism | CSF | Increase in AD | Ref. 180 |

| Aβ1−16 | Amyloidogenic pathway of APP metabolism | CSF | Marked increase in AD | Ref. 37 |

| Endogenous Aβ antibodies | Produced by of truncated amyloid-β isoforms | Blood, CSF | Increases, decreases, or remain unchanged | Refs. 38–40,109, and 110 |

| VLP-1 | Highly expressed neuronal calcium sensor | CSF | Marked increase in AD | Ref. 112 |

| F2-IsoPs | Radical-catalyzed | CSF | Increase in AD | Ref. 181 |

| miRNAs | Post-transcriptional regulation | Blood, CSF | Upregulated or downregulated in AD | Ref. 45 |

| exRNAs | Reflecting pathological states | Blood, CSF | Upregulated in AD | Ref. 46 |

| Exosomes | Neuroinflammatory mediators | Blood, CSF | Reduction and clearance of Aβ | Ref. 47 |

2.2. Core biomarkers

AD core biomarkers are the objective measurements of biological or pathogenic processes, combined with the underlying molecular pathology of the disease for the evaluation of disease risk or prognosis, guidance of clinical diagnosis, or monitoring of therapeutic interventions.24 Currently, the main representatives of core biomarkers include Aβ1−42,8,25,26 Aβ1−42/Aβ1−40,25,27 soluble oligomeric Aβ and Aβ protofibrils,15,16,17 p-tau protein,10,11 and t-tau28,29,30 (Table 1). Based on these biomarkers, drugs have been developed to reflect the pathology of amyloid and neurofibrillary tangle pathology and axonal degeneration in AD.

2.3. Novel biomarkers

Except for Aβ, t-tau, and p-tau, many other candidate biomarkers include β-site amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1),31,32 APP isoforms,33,34,35 truncated Aβ isoforms,14,36,37 endogenous Aβ autoantibodies,38,39,40 neuron and synaptic markers,41 and F2-isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs).42,43,44 These biomarkers show high sensitivity and specificity for AD, which are confirmed by at least two independent studies. Besides, micro-RNA (miRNA),45 extracellular RNAs (exRNAs),46 and exosomes,47 as promising biomarkers of AD, have shown potential in effectively identifying patients with increased pathological risk of AD.

3. Development of Immunosensors for AD Detection

Recently, various immunosensors have been developed and applied for AD detection, mainly including ELISA,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57 modified sandwich ELISA (Fig. 3(a)),58 aptamer sensor assay,59,60,61 electrochemical biosensor (Fig. 3(b)),62,63,64 spectral assay (Fig. 3(c)),65,66 and single-molecule array (SiMoA).67,68 ELISA is the first developed immunosensor to detect AD biomarkers, which is based on a pair of antibodies that recognize different epitopes on the surface of antigens. Presently, the developed diagnostic tools mainly rely on traditional antibodies. Of note, another new type of “molecular antibody” named aptamers is single-stranded DNA or RNA (ssDNA or ssRNA), which has a unique tertiary structure that enables it to specifically bind to homologous molecular targets.69,70 Due to several obvious advantages such as smaller size and nucleic acid characteristics, aptamer-based diagnosis provides a promising opportunity for AD diagnosis. Electrochemical biosensors have been proposed as an important strategy for biomarkers sensing, with pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 level of detection capabilities. Presently, various electrochemical biosensors have been used in AD diagnosis and have provided promising results. SiMoA is an ultrasensitive technology that can detect proteins in blood at sub-femtomolar concentrations (e.g., 10−16 M). Several SiMoA assays have been made in the diagnosis of AD that combined core biomarkers, including Aβ1−40,71 Aβ1−42,72 t-tau,73 and p-tau.74

Recently, a susceptible optical analysis platform based on immuno-infrared sensor and surface plasmon resonance has been reported, which verifies clinical relevance by measuring Aβ1−42 in plasma.75,76 Kim et al. employed a densely aligned single-walled carbon nanotube (CNT) sensor array to realize clinically accurate detection of multiple AD core biomarkers (Aβ1−42, t-tau, and p-tau181) and composite biomarkers (t-tau/Aβ42, p-tau/Aβ42, and Aβ42/Aβ40) in human plasma, and the effective distinction between AD patients and healthy controls (HC) with a mean sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 90%.77 Thus, nanoparticle-based electrochemical biosensors have the potential for early AD diagnosis in the future.

4. Application of Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of AD

4.1. Aβ-based detection

Aβ is the typical product produced in cell metabolism and secreted into CSF and plasma and can be used to diagnose AD patients.78,79 Unfortunately, the results of the CSF test report on Aβ were disappointing, and the results ranged from a slight decrease in AD to no change.80,81,82 Subsequent research results showed that Aβ1−42, as the primary component of plaques, are derived from APP and is the most abundant species of Aβ in amyloid plaques.83,84,85 Various ELISA-related assays and several novel sensors were developed and used for AD tests. Compared with age-matched healthy elderly, the results of the CSF test of AD patients always show a level drop of about 50%.10 Later, soluble oligomeric Aβ, mainly including Aβ protofibrils, exhibited more neurotoxicity and induced more electrophysiological effects on neurons.86,87,88 Several groups demonstrated that soluble Aβ protofibrils could be excreted into CSF and plasma, and their concentration was correlated with plaque burden, which provides the earliest clue for predicting the pathological progress of AD.1

Recently, a sensitive electrochemical detection using interdigital chain electrodes was developed to detect Aβ1−42 in human serum with the detection limit of 100pg⋅⋅mL−1−1, which was much lower than the detection of CSF Aβ1−42 (Fig. 3(b)).64 The immuno-infrared sensor is a novel detection method for detecting β-sheet Aβ in CSF and plasma, with excellent clinical diagnosis accuracy (90% for CSF and 84% for blood) (Fig. 3(c)).66 Later, Nabers et al.89 further used the immuno-infrared sensor and the tau secondary structure distribution in plasma and CSF as a structure-based biomarker for AD diagnosis, achieving an overall specificity of 97%. Recently, Zhang et al.90 developed a sandwich ELISA that could simultaneously detect Aβ1−42 monomers and oligomers as two core biomarkers of AD, improving the sensitivity and accuracy of detection. To compare the detection sensitivity and specificity from different studies, Table 2 summarizes 39 studies on the detection of Aβ in CSF and plasma, including about 3183 AD patients and 2202 controls with the mean specificity of 84.1% and the mean sensitivity of 82.3% to AD.

| Epitope | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comparator group(s) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ1−42 | 376pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 51 | 67 | AD (n = 54), HC (n = 15) | Ref. 182 |

| Aβ1−42 | 256fmol⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 55 | 47 | AD (n = 93), HC (n = 41) | Ref. 183 |

| Aβ1−42 | 475pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 61 | 80 | AD (n = 81), HC (n = 51) | Ref. 184 |

| Aβ1−42 | 738ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 63 | 95 | FTD (n = 34), AD (n = 74), and HC (n = 40) | Ref. 185 |

| Aβ1−42 | 0.49ng⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 73 | 90 | AD (n = 51), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 186 |

| Aβ1−42 | 500pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 76 | 78 | AD (n = 41), HC (n = 21) | Ref. 187 |

| Aβ1−42 | 192pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 78 | 76.9 | AD (n = 102), MCI (n = 200), and HC (n = 114) | Ref. 188 |

| Aβ1−42 | 550ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 78 | 83 | AD (n = 248), SMC (n = 131) | Ref. 189 |

| Aβ1−42 monomer | 150pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 78 | 90 | AD (n = 36) | Ref. 190 |

| Aβ1−42 | 500pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 78 | 82 | AD (n = 93), NAD (n = 33), and HC (n = 54) | Ref. 191 |

| Aβ1−42 | NA | 80 | 85 | AD (n = 18), HC (n = 13) | Ref. 192 |

| Aβ1−42 | NA | 81 | 82 | NA | Ref. 193 |

| Aβ1−42 | 505ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 81 | 76 | AD (n = 57), MCI (n = 56), and OD (n = 21) | Ref. 194 |

| Aβ1−42 | NA | 81 | 74 | MCI (n = 21), sMCI (n = 21), and HC (n = 26) | Ref. 195 |

| Aβ1−42 xMAP | 209ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 82 | 71 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 196 |

| Aβ1−42 MSD | 523ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 85 | 89 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 196 |

| Aβ1−42 | 157ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 87 | 76 | AD (n = 118), sMCI (n = 165), and HC (n = 169) | Ref. 197 |

| Aβ1−42 | 192ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 92.4 | NA | HC (n = 169), AD (n = 118), sMCI (n = 165), and pMCI (n = 59) | Ref. 198 |

| Aβ1−42 | NA | 89 | 79 | AD (n = 158), NAD (n = 233) | Ref. 199 |

| Aβ1−42 | 1130pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 89 | 95 | AD (n = 53), HC (n = 21) | Ref. 200 |

| Aβ1−42 | 361pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 89 | 95 | AD (n = 14), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 201 |

| Aβ1−42 | 537pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 90 | 85 | AD (n = 60), HC (n = 32) | Ref. 48 |

| Aβ1−42 | 505pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 90 | 94 | AD (n = 9), HC (n = 17) | Ref. 51 |

| Aβ1−42 | NA | 92 | 95 | AD (n = 74), HC (n = 40) | Ref. 202 |

| Aβ1−42 | 0.49ng⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 93 | 90 | AD (n = 51), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 203 |

| Aβ1−42 | 537pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 93 | 85 | AD (n = 560), FTD (n = 517), and HC (n = 532) | Ref. 51 |

| Aβ1−42 | 638pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 94 | 94 | AD (n = 19), HC (n = 17) | Ref. 49 |

| Aβ1−42 | 643pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 95 | 81 | AD (n = 150), HC (n = 100) | Ref. 50 |

| Aβ1−42 | 284.1pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 96 | 95 | AD (n = 24), HC (n = 19) | Ref. 52 |

| Aβ1−42 | 490pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 96 | 80 | AD (n = 49), HC (n = 49) | Ref. 53 |

| Aβ1−42 | 375pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 96.4 | 100 | AD (n = 27), HC (n = 49) | Ref. 54 |

| Aβ1−42 | 505pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 100 | 63 | AD (n = 37), OND (n = 32), and HC (n = 20) | Ref. 132 |

| Aβ1−42 | 445pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 100 | 85 | AD (n = 38), HC (n = 47) | Ref. 55 |

| Aβ1−42 | 716ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 100 | 95 | AD (n = 20), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 56 |

4.2. Tau-based detection

As another core biomarker, tau protein consists of six different isoforms formed by alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10. It is an axonal protein that is located in the axons of human brain neurons and binds to microtubules to help keep the microtubules stable and assemble them in bundles.4,11 Tau protein is highly expressed in nonmyelinated cortical axons, especially in memory consolidation areas. In 1993, Vandermeeren et al.28 first reported that the concentration of tau protein in CSF was likely involved in AD pathology and could be used as a polyclonal antibody (pAb)-based ELISA biomarker. Later, an mAb-based ELISA method was developed to detect all isoforms of tau proteins regardless of their degree of phosphorylation.29,30 Compared with approximately 50% reduction in CSF Aβ1−42, the CSF t-tau levels of AD patients increased significantly, which was about three times higher than that of age-matched healthy elderly adults using t-tau-based assays.10 Notably, the concentrations of t-tau in CSF have been found in alcoholic dementia and chronic neurological disorders (for example, Parkinson’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy) through several differential diagnoses.29,51,91,92,93,94 “Innogenetics ELISA” (Fig. 3(a)), as the most commonly used t-tau-based method, revealed an average specificity of 85% and an average sensitivity to AD of 79.4% from 46 different studies, including approximately 4549 AD patients and 2682 controls (Table 3).

| Epitope | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comparator group(s) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-tau | 496.1pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 31 | 94 | AD (n = 55), NAD (n = 23), and HC (n = 34) | Ref. 91 |

| t-tau | 474pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 40 | 86 | AD (n = 93), HC (n = 41) | Ref. 183 |

| t-tau | 400pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 58 | 88 | AD (n = 81), OD (n = 43), and HC (n = 33) | Ref. 204 |

| t-tau | 375pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 59.1 | 89.5 | AD (n = 366), HC (n = 316) | Ref. 205 |

| t-tau | 312pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 59.4 | 92 | AD (n = 37), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 132 |

| t-tau | 0.53–0.55ng⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 63 | 89 | AD (n = 5), PAD (n = 25), and HC (n = 16) | Ref. 92 |

| t-tau | NA | 63 | 100 | Manifest AD (n = 43), AD (n = 16), and HC (n = 16) | Ref. 201 |

| t-tau | 559pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 67 | 85 | EAD (n = 21), LAD (n = 21), and HC (n = 18) | Ref. 206 |

| t-tau | Sensitivity plus specificity | 67 | 96 | MCI (n = 21), sMCI (n = 21), and HC (n = 26) | Ref. 195 |

| t-tau | 93pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 69.6 | 92.3 | AD (n = 102), MCI (n = 200), and HC (n = 114) | Ref. 188 |

| t-tau | NA | 72 | 93 | AD (n = 39), SVD (n = 17), FTD (n = 14), and HC (n = 12) | Ref. 207 |

| t-tau | 380pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 77 | 92 | AD (n = 47), FTD (n = 14), VAD (n = 16), and HC (n = 12) | Ref. 183 |

| t-tau | 51pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 78 | 83 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 196 |

| t-tau | 252pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 79 | 70 | AD (n = 150), HC (n = 100) | Ref. 50 |

| t-tau | 370pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 79 | 100 | AD (n = 52), VAD (n = 46), and HC (n = 56) | Ref. 100 |

| t-tau | 424pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 79 | 82 | AD (n = 560), FTD (n = 517), and HC (n = 532) | Ref. 51 |

| t-tau | 55ng⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 80 | 85 | AD (n = 25), HC (n = 19) | Ref. 204 |

| t-tau | 380pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 81.3 | 91 | AD (n = 80), PAD (n = 82), and HC (n = 21) | Ref. 208 |

| t-tau | NA | 82 | 90 | NA | Ref. 193 |

| t-tau | NA | 83.3 | 84 | NA | Ref. 52 |

| t-tau | 22.6pmol⋅⋅L−1−1 | 84 | 41 | AD (n = 19), FTD (n = 14), ALS (n = 11), and HC (n = 17) | Ref. 49 |

| t-tau | 258pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 84 | 97 | AD (n = 44), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 29 |

| t-tau | 260pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 84 | 62 | AD (n = 38), HC (n = 28) | Ref. 201 |

| t-tau | 7.5pM | 84 | 88 | AD (n = 80), HC (n = 40) | Ref. 209 |

| t-tau | 85% Sensitivity for AD | 85 | 62.7 | AD (n = 529), MCI (n = 750), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 210 |

| t-tau | 375ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 85 | 78 | AD (n = 248), SMC (n = 131) | Ref. 189 |

| t-tau | 260pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 85.4 | 95 | AD (n = 41), HC (n = 17) | Ref. 206 |

| t-tau | 320ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 86 | 56 | AD (n = 529), MCI (n = 750), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 184 |

| t-tau | 334.2pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 87 | 93 | AD (n = 54), HC (n = 15) | Ref. 182 |

| t-tau | 225pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 87.5 | 76 | PAD (n = 16), OD (n = 20), and HC (n = 16) | Ref. 195 |

| t-tau | 317pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 88 | 96 | AD (n = 49), HC (n = 49) | Ref. 53 |

| t-tau | 440pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 89 | 74 | AD (n = 27), HC (n = 49) | Ref. 54 |

| t-tau | 46.3pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 89 | 100 | AD (n = 69), CVD (n = 21), and HC (n = 17) | Ref. 210 |

| t-tau | 295pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 89.5 | 91.5 | AD (n = 38), HC (n = 47) | Ref. 55 |

| t-tau | 305pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 90 | 67 | AD (n = 81), HC (n = 51) | Ref. 184 |

| t-tau | 360ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 90 | 90 | AD (n = 20), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 56 |

| t-tau | NA | 90 | 67 | AD (n = 81), HC (n = 15) | Ref. 193 |

| t-tau | 302pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 93 | 86 | AD (n = 407), HC (n = 93) | Ref. 94 |

| t-tau | 254.5ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 95 | 98 | AD (n = 74), FTD (n = 34), and HC (n = 40) | Ref. 185 |

| t-tau | 306pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 95 | 94 | AD (n = 43), HC (n = 18) | Ref. 182 |

| t-tau | 4fmol⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 97.2 | 56 | AD (n = 36), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 135 |

| t-tau | 22.6pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 98.6 | 100 | AD (n = 70), NAD (n = 76), and HC (n = 17) | Ref. 211 |

Many studies have confirmed that the phosphorylation status of tau in the brain is more related to the progression of AD, which may be reflected in the concentration of p-tau protein in the CSF.11 Soluble hyper-p-tau causes neuronal dysfunction before its aggregation and subsequently forms tangles,95,96 because the accumulation of hyper-p-tau in the somatodendritic compartment of neurons interferes with neuronal functions.97,98 Ittner and Götz4 reported that approximately 84 putative phosphorylation sites are shown in tau, including 45 serines (S), 35 threonines (T), and four tyrosines (Y), and p-tau (181),99 p-tau (231),29 p-tau (396), and p-tau (404)100 are the recently discovered AD biomarkers and have been used in a variety of ELISA tests. Results from several p-tau-based methods consistently report a significant increase in p-tau in the CSF of AD.10 Unlike t-tau protein, no changes in p-tau protein concentration have been observed in acute stroke and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD).101 In 2012, Nakamura et al.102 demonstrated that p-tau (231) is a potential new approach for the early diagnosis and treatment of AD because p-tau (231) is the first detectable phosphorylation event in human AD, and cis p-tau (231) and its ratio to trans might be better and easier than standardized biomarker, especially for the early diagnosis and patient comparison.103 Janelidze et al.104 and Thijssen et al.105 also reported that the concentration of p-tau (181) in the plasma of AD patients increased by 3.5 folds compared with the control group. In conclusion, plasma p-tau (181) is a prognostic biomarker of AD and will benefit for AD diagnosis in clinical practice and trials. Taken together, the concentration of p-tau protein in CSF or plasma can more specifically reflect the state of AD than Aβ. The specificity and sensitivity values of the p-tau-based test are summarized in Table 4 from 40 different studies, including about 3686 AD patients and 1878 controls, with the mean specificity of 84.5% and the mean sensitivity of 78.3% to AD. It is worth noting that compared with other p-tau, p-tau (181) and p-tau (231) show better detection performance in terms of mean specificity and sensitivity in AD diagnosis.

| Epitope | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comparator group(s) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-tau (181) | 21.2pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 40 | 81.4 | AD (n = 23), PAD (n = 50), VAD (n = 39), and HC (n = 27) | Ref. 212 |

| p-tau (181) | 12.5pmol⋅⋅L−1−1 | 44 | 95 | AD (n = 41), FTD (n = 18), and HC (n = 17) | Ref. 206 |

| p-tau | 51pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 50 | 94 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 213 |

| p-tau (231) | 3.6fmol⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 52.8 | 100 | AD (n = 36), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 135 |

| p-tau (181) | 51ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 57.4 | 82.9 | AD (n = 215), HC (n = 38) | Ref. 214 |

| p-tau (181) | 22.6pmol⋅⋅L−1−1 | 58 | 95.3 | AD (n = 19), HC (n = 17) | Ref. 49 |

| p-tau | 59pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 64 | 98 | AD (n = 57), HC (n = 45) | Ref. 215 |

| p-tau (231) | 52ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 68 | 73 | AD (n = 529), MCI (n = 750), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 199 |

| p-tau (181) | 73pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 71 | 94 | Manifest AD (n = 43), incipient AD (n = 8), and HC (n = 16) | Ref. 201 |

| p-tau (181) | 61ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 73.1 | 93.1 | AD (n = 67), HC (n = 72) | Ref. 216 |

| p-tau (181) | 51ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 73.5 | 75.7 | NA | Ref. 217 |

| p-tau (181) | 15pmol⋅⋅L−1−1 | 75.3 | 81.8 | AD (n = 18), FTD (n = 26), and HC (n = 13) | Ref. 218 |

| p-tau (181) | NA | 77.6 | 87.9 | NA | Ref. 219 |

| p-tau | NA | 80 | 83 | NA | Ref. 193 |

| p-tau (181) | 50pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 83.3 | 84.6 | AD (n = 18), HC (n = 13) | Ref. 192 |

| p-tau (181) | 10pmol⋅⋅L−1−1 | 83.8 | 87.5 | AD (n = 80), HC (n = 40) | Ref. 209 |

| p-tau (181) | 33pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 84 | 84 | AD (n = 51), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 186 |

| p-tau | 52ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 84 | 47 | AD (n = 529), MCI (n = 750), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 184 |

| p-tau | 33pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 84 | 84 | AD (n = 51), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 203 |

| p-tau (181) | 33pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 84.3 | 83.9 | AD (n = 100), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 220 |

| p-tau (231) | 10.1ng⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 85 | 97 | AD (n = 27), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 201 |

| p-tau | 52ng⋅⋅L−1−1 | 85 | 68 | AD (n = 248), SMC (n = 131) | Ref. 189 |

| p-tau (199) | 1.1fmol⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 85 | 82 | AD (n = 108), HC (n = 23) | Ref. 221 |

| p-tau (181) | 14.3pmol⋅⋅L−1−1 | 85 | 91 | AD (n = 108), HC (n = 23) | Ref. 221 |

| p-tau (181) | 54pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 85.1 | 76.2 | AD (n = 28), HC (n = 13) | Ref. 222 |

| p-tau (231) | 10.1ng⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 85.2 | 96.8 | AD (n = 27), NAD (n = 4) | Ref. 223 |

| p-tau (181) | 14.3pmol⋅⋅L−1−1 | 87 | 88.9 | AD (n = 93), NAD (n = 33), OND (n = 56), and HC (n = 54) | Ref. 191 |

| p-tau (231) | 250pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 88 | 92 | AD (n = 108), HC (n = 23) | Ref. 221 |

| p-tau | 1140pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 88 | 89 | AD (n = 40), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 29 |

| p-tau (181) | 65pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 88.2 | 79.5 | AD (n = 76), NAD (n = 48), and HC (n = 39) | Ref. 224 |

| p-tau (231) | 19pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 90.2 | 80 | AD (n = 80), PAD (n = 82), VAD (n = 20), and HC (n = 21) | Ref. 48 |

| p-tau (231) | 18.1pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 90.3 | 80 | AD (n = 82), HC (n = 21) | Ref. 205 |

| p-tau (181) | 8.1pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 91.7 | 83.8 | AD (n = 56), MCI (n = 47), and HC (n = 69) | Ref. 105 |

| p-tau (181) | 1.81pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 92 | 87 | Aβ+β+ MCI (n = 109), Aβ+β+ AD (n = 38), and NAD (n = 52) | Ref. 104 |

| p-tau (231) | 18.1pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 92.2 | 85.3 | Possible AD (n = 17), PAD (n = 64), and HC (n = 21) | Ref. 225 |

| p-tau (199) | 3.2fmol⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 94.4 | 80 | AD (n = 36), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 135 |

4.3. Assays based on novel biomarkers

Several promising detection methods for novel blood biomarkers have been documented. Here, we review these promising diagnosis analyses. The amount of Aβ directly relies on the activities of β-secretase and γγ-secretase on APP, among which BACE1 is the main enzyme responsible for β-secretase activity.10 BACE1 can be measured in the CSF of AD patients and prodromal AD cases with a marked increase in the concentration and activity of BACE1, indicating that the upregulation of BACE1 may be an early event of AD.33,106,107 Much attention has been focused on the Aβ1−42/Aβ1−40 ratio12,13,14 and the application of other truncated amyloid-β isoforms in the diagnosis of AD. Individuals with elevated Aβ1−38 levels in CSF are accompanied by a decrease in Aβ1−42,14,36 suggesting that the ratio of Aβ1−42/Aβ1−38 may improve the diagnostic accuracy of AD. Besides, it has been reported that there is a significant increase in Aβ1−16 in the CSF of AD patients and an expected decrease in Aβ1−42.37 Portelius et al.108 used immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry to determine other truncated Aβ subtypes at the carboxyl terminus, which may be useful for the diagnostic testing of AD. Different kinds of truncated Aβ isoforms are secreted into CSF or blood to produce various endogenous amyloid-β autoantibodies, of which oligomeric Aβ shows the highest antibody reactivity. The study aimed to detect the titers of such antibodies, but the results were inconsistent, with increases,38,109 decreases,39,110 or remaining unchanged.40 Disappointingly, the level of endogenous oligomeric Aβ autoantibodies did not differ between AD cases and controls.111

Visinin-like protein 1 (VLP-1) and neurofilament are representative biomarkers of neurons and synapses. VLP-1 is a neuronal calcium-sensing protein, which is abundantly expressed in the central nervous system and retinal neurons, and its expression level is significantly increased in AD, especially when carrying the apolipoprotein E (APOE) εε4 allele.41 The sensitivity and specificity of VlP-1-based assays are all close to 80%, which is sufficient to distinguish AD from age-matched individuals and comparable to CSF t-tau, p-tau, and Aβ1−42.112 Considering its good diagnostic performance, VlP-1 is regarded as a promising candidate CSF biomarker for AD. Besides, neurofilament is a structural component of axons, especially highly expressed in vascular dementia (VAD), normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), but it is expressed at normal levels in most AD patients.113,114,115 Thus, neurofilaments help differentiate AD from VAD, NPH, and FTD.

In AD, neurons are mainly injured by Aβ, neurofibrillary tangles, and free radicals. F2-IsoPs are the products formed by free radical-mediated oxidation of arachidonic acid. Compared with healthy elderly or non-AD dementia patients, AD patients have higher F2-IsoP CSF levels, including the prodromal AD in individuals with cognitive impairment and asymptomatic carriers of familial AD mutations.42,44,116 However, the measurement of F2-IsoPs in plasma had contradicted CSF because brain-derived F2-IsoPs are much smaller than peripheral F2-IsoPs.42

Besides, Cheng et al. reported that 12 miRNAs can discriminate AD from healthy controls with an average accuracy of 93%.45 A recent review of miRNAs as AD biomarkers reported that 136 individual miRNAs changed significantly between AD and healthy states.117 Compared with age-matched control plasma, plasma phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) exRNA levels have also been confirmed to exhibit a statistically significant increase in AD.46 These miRNAs and exRNAs are thought to be transported within extracellular vesicles such as exosomes, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), neuronally derived extracellular vesicles, and other degrading proteins. Exosomes play an essential role in triggering Aβ pathogenesis and tau hyperphosphorylation, and in mediating the clearance and accumulation of Aβ and tau.47 Lim et al. developed an amplified plasma exosome system to define the exosome-bounded Aβ population from AD blood samples, and confirmed that the exosome-bounded Aβ level was correlated with the corresponding PET imaging of brain amyloid plaque deposition.75

5. Performance of Assays Developed Based on Core Biomarkers

5.1. Analysis of PET-based detection methods

Although pathological tau and Aβ represent distinct pathological processes, they are closely related in the context of AD.118 The use of tau and Aβ imaging allows AD-related cognitive dysfunction to be attributed to specific pathological processes and locations in the brain.119 Structural imaging techniques (e.g., MRI) reveal brain atrophy due to neuronal loss. In most cases, the molecular-level functional changes due to degeneration precede brain atrophy and may occur before any cognitive symptom appears.120 Therefore, the use of functional techniques such as single-photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT) and PET for molecular neuroimaging may be a more promising tool for the diagnosis of AD. Presently, PET-based imaging methods can be divided into the following categories: glucose metabolism imaging,121,122,123 Aβ imaging, and tau imaging, of which the latter two are more widely used in AD diagnosis.

Aβ deposition is one of the pathological hallmarks of AD in the cerebral cortex. It starts many years before the onset of symptoms and reaches a plateau when the first cognitive impairment becomes clear.118,124 Currently, many radiotracers for Aβ molecular imaging of PET have been developed. Aβ PET imaging is highly sensitive to Aβ detection, but the specificity of Aβ-positive PET is relatively low because an increased 11C-PiB uptake has also been found in 30% of ordinary older adults without cognitive impairment and other causes of neurodegenerative dementia.125 In addition, compared with 11C-PiB, fluorinated tracers show more nonspecific white matter absorption, resulting in higher background noise, which may mask the absorption of tracers in the cortex, especially when using visual analysis.125 Therefore, there is an urgent need for an objective and widely applicable method to reveal a small number of Aβ deposits and determine the optimal cut-off level, which makes the results of different studies comparable.

On the other hand, pathological tau begins to spread from the temporal lobe to other parts of the brain in the later stage, which is also accompanied by the death of neurons.118,126 Although the phosphorylation concentration of tau is much lower than that of Aβ (4–20 times lower), it provides multiple binding sites due to its larger size compared to Aβ.127 The newly developed tau-PET method has high sensitivity and specificity (about 90–95%) and very few false-positive results for patients with other diseases.128,129 Compared with MRI, the tau-PET method has significantly higher diagnostic accuracy and fewer false-positive results than Aβ-PET, which may be due to the high p-tau level that has only been found in AD rather than Aβ which is also shown in patients with dementia such as cerebral amyloid angiopathy130 and Lewy bodies.52 In addition, Aβ is related to AD, but not directly related to symptoms, while tau protein, especially the tau protein in the temporal lobe region, is more closely related to cognitive decline in cognitive tests.119

5.2. Analysis of CSF-based detection methods

AD pathology is mainly restricted to the brain; therefore, an accurate and timely diagnosis of AD is essential for scientific understanding of brain function, activities, and the status of health, disease, and repair. Since the CSF is in direct contact with the extracellular space of the brain, the biochemical changes in the brain are directly reflected in the cerebrospinal fluid.11 At present, Aβ in CSF has been widely used for the early diagnosis of AD in preclinical and clinical studies. However, subsequent studies have shown that CSF Aβ1−42 are also significantly reduced in CJD,116 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS),49 FTD and VAD, and multiple system atrophy diseases (MSADs)131 without Aβ plaque. These results from the Aβ1−42 assays at least confirm that Aβ1−42 are not sufficient to diagnose AD, with a specificity of 82.3% and an average sensitivity of 84.1% for CSF Aβ1−42 to discriminate AD from normal aging in the “Innogenetics ELISA”.48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57 The specificity and sensitivity results based on Aβ1−40/Aβ1−42 assays are compromised. Many t-tau-based ELISA methods have been developed to detect all isoforms of tau protein. In the detection of CJD and VAD, the average specificity is lower because the concentration of tau protein in CSF may not only reflect the intensity of neuronal degeneration in AD, but also reflect the intensity of neuronal degeneration in chronic neurodegenerative diseases.29,50,132 For this reason, the specificity for t-tau-based assays is not optimal to date. The specificity of p-tau (84.5%) seems to be better than Aβ (82.3%) because p-tau is only shown in AD and Myocardial Infarction (MI).133,134,135 Unfortunately, CSF measurement is invasive, with high inter-laboratory variability, and having more side effects, resulting in limited availability, especially in primary care.

5.3. Analysis of plasma-based detection methods

The analysis of blood biomarkers is cost-effective and can be performed by minimally invasive surgery, which is of great significance for the early diagnosis of AD.136 Reliable serum or plasma biomarkers are the key to timely treatment and help preventing the patient’s condition from getting worse, but only a few studies have been reported. Some studies have tested plasma Aβ as a biomarker of AD, but the results are inconsistent, ranging from no change in plasma Aβ to slightly higher Aβ1−42 or Aβ1−40 plasma levels in AD than those in healthy age-matched controls.137,138 The conflicting results have originated from the fact that there is a wide overlap in the levels of Aβ1−42 and Aβ1−40 in plasma Aβ values between preclinical AD and non-AD. Also, high levels of plasma Aβ1−42 or large Aβ1−42: Aβ1−40 ratios are risk factors for AD, while other studies have reported the opposite data.138,139,140,141 The phenomena could be explained because plasma Aβ is derived from peripheral tissues and does not reflect brain Aβ turnover or metabolism.14 Besides, the majority of Aβ in plasma is hydrophobic and needs to bind to plasma proteins, leading to epitope masking and other analytical interferences.142 Based on β-sheet Aβ, which mainly includes oligomers, many detection methods have been developed, such as ELISA,143 immuno-infrared sensor,66 and sensitive electrochemical detection,64 but the specificity directly depends on the antibodies. For Aβ oligomers, as intermediates in the Aβ aggregation process, they are mainly synthesized by Aβ1−42 or Arctic-mutant Aβ1−42(E22G). However, the antibody detection methods based on Aβ oligomers need to overcome the challenge of distinguishing Aβ1−42 or Aβ1−42(E22G) surface epitope antibody recognition from Aβ fibrils. In addition, antibodies that cross-react with Aβ1−42 or Aβ1−42(E22G) may cause false positives.

Many mAbs, such as mAb 158,143 3D6, MOAB-2,64 211F12, 6E10,66 BAN2401 (humanized IgG1 monoclonal),144,145 and 1F12 and 2C6,90 have been developed to target Aβ. Of note, 6E10 and mAb 158 or its mutant BAN2401 (humanized IgG1 mAb) have superior performance and are widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of AD. However, 6E10 reacts with almost all forms at the NN-terminus, making it difficult to distinguish different Aβ forms, largely limiting its application in diagnosis. On the contrary, it has been confirmed that mAb 158 and its mutant BAN2401 are at least 1000-fold higher in selectivity for protofibrils than monomers, and the binding to protofibrils is 10–15 times higher than the binding to fibrils. Besides, 1F12 and 2C6 (with four discrete epitopes) are the Aβ1−42 sequence- and conformation-specific antibodies that can bind to Aβ1−42 species with different conformations, but not the Aβ1−40 or Aβ1−38 species.90 These antibodies provide great prospects in the treatment and diagnosis of AD. Recently, plasma p-tau (181) has been confirmed by two groups as a novel promising biomarker for AD.104,105 Encouraging results indicate that the concentration of plasma p-tau (181) increases in preclinical AD and further increases during the MCI and dementia stages (compared to the control group, the concentration in AD is approximately 3.5 times). Interestingly, the plasma p-tau (181) concentration is correlated with the CSF p-tau (181) concentration and has been successfully used to predict the positive tau PET scans.104,133 Two independent results consistently indicate that p-tau (181) is a noninvasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for AD, and may be useful in clinical practice and trials.

5.4. Analysis of combined biomarkers-based detection methods

Both CSF biomarkers and plasma biomarkers (e.g., Aβ42, t-tau, and p-tau) have high diagnostic value in AD. In other medical fields, CSF or plasma biomarkers should not be used as isolated tests. In in-vitro AD diagnosis, the best choice is to combine CSF or plasma biomarkers detection with a variety of sensitive biosensors, such as electrochemical biosensors, spectrometry, and SiMoA, which can further improve the performance of current single-target assays. However, only a few studies have realized this. A combination of biomarkers in plasma or CSF has been established for the early diagnosis of AD, including tau + Aβ42, low tau+elevated Aβ42, Aβ42/tau, Aβ42/p-tau, tau + Aβ42/p-tau (181), Aβ42 + p-tau, Aβ42 + tau + p-tau, Aβ42/Aβ40, and Aβ42/p-tau + tau. From 73 different studies, the average specificity of 86% and the average sensitivity of 83.5% to AD are summarized in Table 5. The average specificity and sensitivity after combining two or more biomarkers are higher than those of a single biomarker. While two or more combination tests from 73 different studies are performed by using two or more diagnostic test kits, multiple target detection methods based on bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) or multi-targeted antibodies (MtAs) have not been applied to the diagnosis of AD.

| Epitope | Cut-off value(s) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comparator group(s) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-tau + Aβ42/Aβ40 | 474pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 + 13.3 | 49 | 100 | AD (n = 93), HC (n = 41) | Ref. 183 |

| t-tau + Aβ42 | 474pg⋅⋅mL−1−1 + 256fmol⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 50 | 90 | AD (n = 93), HC (n = 41) | Ref. 183 |

| p-tau (231) + p-tau (235) | 0.18fmol⋅⋅mL−1−1 | 53 | 100 | AD (n = 36), HC (n = 20) | Ref. 135 |

| Aβ42/Aβ40 | 13.3 | 56 | 73 | AD (n = 93), HC (n = 41) | Ref. 183 |

| t-tau + elevated Aβ42 | NA | 61.5 | 100 | AD (n = 37), OND (n = 32), and HC (n = 20) | Ref. 132 |

| Aβ42 × t-tau | 3392.9 | 69 | 88 | AD (n = 55), NAD (n = 23), and HC (n = 34) | Ref. 91 |

| t-tau or Aβ42/Aβ40 | 474pg⋅mL−1 or 13.3 | 70 | 72 | AD (n = 93), HC (n = 41) | Ref. 183 |

| t-tau × Aβ40/Aβ42 | 3483 | 71 | 83 | AD (n = 93), HC (n = 41) | Ref. 183 |

| Aβ42/t-tau | NA | 71 | 83 | AD (n = 93), NAD (n = 33), and HC (n = 54) | Ref. 191 |

| p-tau (396)/t-tau | 1 | 73 | 80 | AD (n = 41), HC (n = 120) | Ref. 192 |

| t-tau + Aβ1−42 | Disease state index 0.50 | 73 | 71 | MCI (n = 391) | Ref. 199 |

| t-tau + Aβ42 | NA | 74 | 93 | AD (n = 81), HC (n = 51) | Ref. 184 |

| CSF t-tau | 6fmol⋅mL−1 | 77.1 | 77.6 | AD (n = 236), HC (n = 95) | Ref. 200 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau | 505ng⋅L−1 + 350ng⋅L−1 | 82 | 90 | MCI (n = 56), AD (n = 57), and OD (n = 21) | Ref. 194 |

| Aβ42/p-tau + t-tau | 6.16 + 350ng⋅L−1 | 82 | 94 | MCI (n = 56), AD (n = 57), and OD (n = 21) | Ref. 194 |

| Aβ42xMAP/p-tau + t-tau | 6.6 + 62pg⋅mL−1 | 82 | 85 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| p-tau (396,404) | 120ng⋅L−1 | 83 | 98 | AD (n = 52), VAD (n = 46), and NAD (n = 37) | Ref. 100 |

| t-tau + Aβ42/p-tau (181) | Sensitivity of 85% | 83 | 72 | AD (n = 529), MCI (n = 750), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 184 |

| Aβ42/p-tau + t-tau | Sensitivity of 85% | 83 | 72 | AD (n = 529), MCI (n = 750), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 184 |

| p-tau (404)/t-tau | 1 | 83 | 80 | AD (n = 41), FTD (n = 16), and HC (n = 120) | Ref. 192 |

| Aβ42xMAP/p-tau | 6.6 | 83 | 83 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 196 |

| Aβ42/p-tau | Sensitivity of 85% | 85 | 88 | MCI (n = 750), AD (n = 529), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 199 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau + p-tau | NA | 85 | 86 | NA | Ref. 226 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau | 252pg⋅mL−1 + 643pg⋅mL−1 | 85 | 85 | AD (n = 150), NAD (n = 79), and HC (n = 100) | Ref. 50 |

| Aβ42 + p-tau | NA | 85 | 86 | PAD (n = 27), NAD (n = 24) | Ref. 54 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau | 101pg⋅mL−1 + 150pg⋅mL−1 | 85 | 100 | PAD (n = 27), NAD (n = 24) | Ref. 54 |

| CSF p-tau (199) | 1.05fmol⋅mL−1 | 85 | 88.5 | AD (n = 236), HC (n = 95) | Ref. 200 |

| t-tau/Aβ42 | 0.39 | 85 | 84.6 | AD (n = 102), MCI (n = 200), and HC (n = 114) | Ref. 188 |

| p-tau/Aβ42 | 58 | 85.2 | 97 | AD (n = 51), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 186 |

| Aβ42xMAP/Aβ40 | 0.024 | 85.7 | 70 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| p-tau/Aβ42 | 58 | 86 | 97 | AD (n = 51), HC (n = 31) | Ref. 203 |

| Aβ42MSD/Aβ38 | 0.37 | 86 | 72 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ42MSD/p-tau | 21 | 86 | 82 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ42/p-tau | 6.16 | 87 | 90 | AD (n = 57), MCI (n = 56), and OD (n = 21) | Ref. 194 |

| Aβ42xMAP + tau/Aβ40 | 209pg⋅mL−1 + 0.088 | 88 | 92 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ42/t-tau | 85% Sensitivity | 88 | 82 | AD (n = 529), MCI (n = 750), and HC (n = 304) | Ref. 210 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau | 240pg⋅mL−1 + 1.18pg⋅mL−1 | 88 | 92 | AD (n = 49), VAD (n = 6), and HC (n = 49) | Ref. 53 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau | NA | 88 | 87 | NA | Ref. 193 |

| t-tau/Aβ40 | 0.01 | 88 | 86 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ42xMAP + t-tau | 209pg⋅mL−1 + 62pg⋅mL−1 | 88 | 88 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ42/tau | Sensitivity plus specificity | 89 | 72 | MCI (n = 21), sMCI (n = 21), and HC (n = 26) | Ref. 218 |

| Aβ42MSD/Aβ40 + t-tau | 0.069 + 62pg⋅mL−1 | 89 | 86 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| p-tau (181)/Aβ1−42 | 0.1 | 89 | 71.2 | AD (n = 102), MCI (n = 200), and HC (n = 114) | Ref. 188 |

| t-tau + Aβ42 | 644.3 pg⋅mL−1 + 1.25 ng⋅mL−1 | 90 | 95 | AD (n = 74), FTD (n = 34), and HC (n = 40) | Ref. 185 |

| Aβ42MSD/Aβ40 | 0.069 | 91 | 86 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau + p-tau | NA | 91.1 | 82.7 | AD (n = 248), SMC (n = 131) | Ref. 189 |

| p-tau (396,404) | 100pg⋅mL−1 | 92 | 89 | AD (n = 52), VAD (n = 46), and HC (n = 56) | Ref. 100 |

| t-tau + Aβ42 + p-tau (181) | 350ng⋅L−1 + 530ng⋅L−1+60ng⋅L−1 | 93 | 87 | MCI (n = 180), HC (n = 39) | Ref. 187 |

| t-tau + Aβ42 | 350ng⋅L−1 + 530ng⋅L−1 | 93 | 83 | MCI (n = 180), HC (n = 39) | Ref. 187 |

| t-tau + Aβ42/p-tau (181) | 350ng⋅L−1 + 6.5 | 93.5 | 87 | MCI (n = 180), HC (n = 39) | Ref. 187 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau | Sensitivity plus specificity | 94 | 79 | MCI (n = 21), sMCI (n = 21), and HC (n = 26) | Ref. 195 |

| p-tau (396,404)/t-tau | 0.33 | 95 | 95 | AD (n = 52), VAD (n = 46), and HC (n = 56) | Ref. 100 |

| p-tau (396) + p-tau (404) | NA | 95 | 95 | AD (n = 47), VAD (n = 16), and HC (n = 12) | Ref. 183 |

| p-tau + Aβ42 | NA | 95 | 100 | AD (n = 57), HC (n = 57) | Ref. 191 |

| Aβ42xMAP/t-tau | 2.5 | 96 | 82 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| t-tau/Aβ42 | 0.44 | 96 | 86 | AD (n = 49), VAD (n = 6), and HC (n = 49) | Ref. 53 |

| Aβ42MSD/t-tau | 7.3 | 96 | 83 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| tau + Aβ42 + p-tau (181, 396) | NA | 96 | 100 | AD (n = 57), HC (n = 57) | Ref. 191 |

| Aβ42 + t-tau + APOE | NA | 96 | 80 | AD (n = 102), MCI (n = 200), and HC (n = 114) | Ref. 188 |

| Aβ42MSD/Aβ40 | 0.069 | 96 | 86 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ42MSD/Aβ38 | 0.37 | 97 | 82 | AD (n = 94), MCI (n = 166), and HC (n = 38) | Ref. 211 |

| Aβ40/Aβ42 | 12.76 | 98 | 82 | AD (n = 55), NAD (n = 23), and HC (n = 34) | Ref. 91 |

| p-tau (181, 231) | 1140pg⋅mL−1 | 98.2 | 76 | AD (n = 44), VAD (n = 17), and HC (n = 31) | Ref. 227 |

6. Bispecific or Multi-Targeted Detection

Monoclonal antibodies have been widely used in diagnostics and molecular imaging to monitor biological processes and responses because of their excellent specificity for a single epitope.146,147,148 Due to multiple disease pathways, a single mAb has limited effects on disease detection and treatment.147,148 The development of immunosensors simultaneously targeting two or more biomarkers would be extremely valuable for improving the sensitivity and specificity of detection. Therefore, BsAbs or MtAs will be expected to recognize different antigenic determinants with high binding affinity and specificity.149 More than 85 BsAbs are in clinical development, and some are used in the clinical treatment of diseases but less for clinical diagnosis.150 Compared with mAbs, BsAbs have several advantages, including increased affinity, avidity, and efficacy, making them applicable to molecular imaging and molecular diagnostics. Bispecific antibody fragments are generated by chemical conjugation of the transferrin receptor antibody 8D3 Fab with single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) of the Aβ protofibril selective antibody mAb 158 to visualize Aβ pathology with PET in AD diagnostic imaging.144,151 In contrast, transferrin receptor antibodies facilitated the entry of large molecules such as mAb 158 or scFv-158 into the brain. In our previous study, we developed a series of BsAbs for molecular cancer imaging by combining immuno-PET, near-infrared fluorescence, and nanographene.152,153,154,155 Unfortunately, several advantages of BsAbs or MtAs have not been realized in AD diagnosis or imaging. In the future, we hope that BsAb or MtA strategies can be applied to the diagnosis or imaging of AD or other degenerative neurological diseases.

7. Conclusions

A seismic shift is occurring in the ability of AD diagnosis in the past few decades with more valuable biomarkers are discovered (Fig. 4).156 We have transformed from clinical–pathological diagnosis to several advanced instrument tests that combine AD core biomarkers. However, AD pathology is more complicated, and its early detection is essential for AD intervention, which brings great hope to early diagnosis. So far, the challenge of early diagnosis and identification of AD urgently requires multi-targeted diagnostic tools that can accurately reflect the core elements of the disease process and improve the diagnosis efficiency of clinicians for further understanding the pathogenesis of AD. We expect that BsAbs or MtAs strategy will provide exciting opportunities for diagnosis and have a lasting impact on clinical diagnosis.

8. Future Perspectives

Combined biomarkers improve the performance of these individual biomarkers. Therefore, developing methods by combining biomarkers from PET or MR imaging modalities with CSF/blood and genotype biomarkers is valuable for the early detection of AD. Many patients in preclinical AD testing are reluctant to analyze CSF biomarkers because the procedure is invasive with a lumbar puncture and back pain. In contrast, blood testing is less invasive, but the sensitivity and specificity of detecting blood biomarkers are low. Besides, the methods developed based on blood biomarkers such as ELISA,157,158,159 nanoparticle-based immunoassays,160 electrochemistry,161 surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy,162,163,164 fluorescence,165 and electrochemical biosensors166,167 require devices or/and expertise, which largely restrict their applications. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a simple, user-friendly, and point-of-care diagnosis tool to detect blood biomarkers. As an alternative, the lateral flow immunochromatographic strip (LFIS) is an ideal tool for detecting blood/CSF biomarkers due to its simplicity, portability, cost-effectiveness, and rapid detection, which has been widely used for the rapid diagnosis of blood biomarkers.168,169,170,171

BsAbs or MtAs can specifically recognize two or more core plasma biomarkers such as Aβ1−42, Aβ protofibril, and p-tau, which is of utmost importance for the early diagnosis of AD. Therefore, the use of blood organisms with multi-biomarker measurements such as multi-target lateral flow immunoassay strips for the diagnostic screening step followed by PET or MR imaging will quickly achieve rapid, noninvasive, high-quantitative, and low-cost clinical application. In clinical AD diagnosis, molecular imaging allows in-vivo visualization and quantification of Aβ or tau pathology. Multi-target probes combined with advanced equipment such as PET and MRI can improve the diagnostic accuracy of AD or other diseases.

Author Contributions

Haiming Luo coordinated the writing of the review, provided writing guidance, and did manuscript revision. Liding Zhang contributed to writing the first draft. Xiaohan Liang contributed to table preparation. Zhihong Zhang provided valuable revised suggestions. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81971025) and the Startup Fund of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 0214187096).