Deep-skin third-harmonic generation (THG) imaging in vivo excited at the 2200 nm window

Abstract

The skin is heterogeneous and exerts strong scattering and aberration onto excitation light in multiphoton microscopy (MPM). Shifting to longer excitation wavelengths may help reduce skin scattering and aberration, potentially enabling larger imaging depths. However, previous demonstrations of skin MPM employ excitation wavelengths only up to the 1700nm window, leaving an open question as to whether longer excitation wavelengths are suitable for deep-skin MPM. Here, in order to explore the longer-wavelength territory, first, we demonstrate characterization of the broadband transmittance of excised mouse skin, revealing a high transmittance window at 2200nm. Then, we demonstrate third-harmonic generation (THG) imaging in mouse skin in vivo excited at this window. With 9mW optical power on the skin surface operating at 1MHz repetition rate, we can get THG signals of 250μm below the skin surface. Comparative THG imaging excited at the 1700nm window shows that as imaging depth increases, THG signals decay even faster than those excited at 2200nm. Our results thus uncover the 2200nm window as a new, promising excitation window potential for deep-skin MPM.

1. Introduction

The skin is the largest organ and the first defense barrier of the body with the main functions of protection, regulation, and sensation. In order to visualize and investigate skin structures and their functions with cellular resolution, optical imaging is an indispensable technology. Among the various optical imaging modalities, multiphoton microscopy (MPM) has its unique niche due to its three-dimensional (3D) sectioning, lower tissue scattering due to long excitation wavelength, and intrinsic multiphoton signal generation mechanism, including second/third harmonic and endogenous multiphoton fluorescence.1,2,3 As a result, MPM can acquire the structures and capture the dynamics of skin in vivo, in animal models and even on human subjects.4,5,6,7

Skin is a multilayered structure and thus highly heterogenous. Tissue heterogeneity is known to impose dramatic scattering and aberration onto the excitation light,8,9 which degrades MPM signal levels and resolution as imaging depth increases. A potential solution to reducing tissue scattering and aberration is shifting to longer excitation wavelengths.10,11,12 When choosing an excitation wavelength for MPM, tissue absorption is another factor that needs consideration. For most biological tissues, the major component is water. So excitation wavelengths typically lie within low water absorption windows. So far, three excitation windows have been demonstrated as suitable for skin MPM— the 800, 1300 and 1700nm window. Among them, the 1700nm window is especially suitable for deep-skin MPM.13,14,15 However, it remains unknown whether there is a longer excitation window suitable for deep-skin MPM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental setup

Through both water absorption and tissue transmittance measurements, it has been shown that water absorption reaches a local minimum, and biological tissue transmittance reaches a local maximum at the 2200nm window (roughly 2060–2400nm).16,17,18 These measurements imply that the 2200nm window is a potential excitation window for deep-skin MPM.

A spectrometer (Lambda 900, Perkin Elmer) was used to measure the broadband transmittance of the freshly excised mouse skin, spanning from 500nm to 2500nm. A pinhole with a diameter of ∼2mm was placed in front of the skin to sample a relatively uniform area. The whole spectrum was acquired with a 2nm step in wavelength.

However, due to the lack of proper instrumentation at this window, skin MPM has never been demonstrated. Recently, we have developed a fiber-based 2200nm femtosecond laser and the corresponding laser scanning microscope.19 It is our aim in this paper to explore skin MPM in this long excitation window, focusing on imaging depth, signal level, spatial resolution, and its comparison with the 1700nm window.

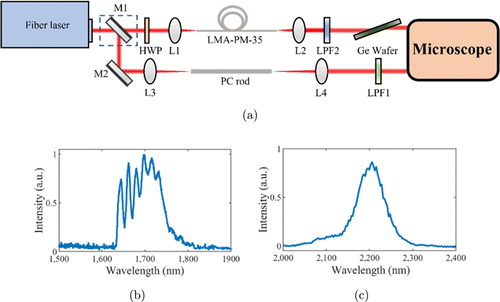

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1(a) and similar to Ref. 19. Both 2200nm and 1700nm femtosecond pulses were generated through the nonlinear optical effect of soliton self-frequency shift (SSFS)20,21 pumped by a 1550nm, 1MHz, 500fs fiber laser (FLCPA-02CSZU, Calmar), but in different optical waveguides. 2200nm pulses were generated in a 65cm largemode-area (LMA-PM-35, NKT Photonics) fiber. The optical spectrum measured after a 2055nm long-pass filter (LP-2055nm, Spectrogon) was shown in Fig. 1(c). A 2mm germanium wafer placed at Brewster angle compressed the pulse width on the sample to 98fs.19 Pumped by the same fiber laser, the 1700nm soliton pulses were generated in a 44cm photonic-crystal rod (SC-1500/100-Si-ROD, NKT Photonics), with a measured spectrum shown in Fig. 1(b) filtered by a 1635nm long-pass filter (1635LPF, Omega Optical). The pulse width on the sample was 88fs.

Fig. 1. Experimental setup (a). L1: f=50mm lens; L2: f=40mm lens; L3: f=100mm lens; L4: f=75mm lens; LPF1: 2055nm long-pass filter; LPF2: 1635nm long-pass filter; HWP: half-wave plate; M1, M2: silver-coated mirror, M1 is removable to switch the path between 2200nm and 1700nm; LMA: 65-cm large-mode-area fiber, PC rod: 44-cm photonic-crystal rod. (b) Measured 1700nm soliton spectrum. (c) Measured 2200nm soliton spectrum.

The optics in the laser scanning microscope (MOM, Sutter) was optimized for the 2200nm window. Both the scan lens (LA5763-D, Thorlabs) and the tube lens (ACA254-200-D, Thorlabs) have high transmittance at the 2200nm window. Among the various immersion objective lenses, a numerical aperture (NA)=1.05 water-immersion objective lens (XLPLN25XWMP2-SP1700, working distance=2mm, Olympus) was chosen based on its measured transmittance.22 The objective lens was underfilled to avoid extra loss of power on the sample (the effective NA is 0.53 for both excitations). D2O immersion was used instead of H2O immersion, due to its lower absorption coefficient at the 2200nm window 16. Third-harmonic generation (THG) signals were epi-detected by the same GaAs PMT (H7422p-50, Hamamatsu) for both excitations, but with different bandpass filters: for 2200nm THG, a 732/68nm bandpass filter (FF01-732/68-25, Semrock) was used, while for 1700nm THG, a 560/94nm bandpass filter (FF01-560/94-25, Semrock) was used.

The maximum optical power of the 2200nm excitation on the sample was 9mW with both optics and immersion medium considered. For skin imaging, the acquisition speed was 2ms/line with 2 averages, with a resultant frame rate of 0.5frame/s for a pixel size of 512×512.

2.2. Animal procedures

Animal procedures were reviewed and approved by Shenzhen University. Measurements and imaging were carried out on Balb/C mice (12–14 weeks old, Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center). For in vivo imaging, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane using a gaseous anesthesia system (Matrx VIP 3000, Midmark). Body temperature was kept at ∼37∘C with a heating pad. The dorsal skin was depilated and rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline before imaging. The skin was fixed by a homemade titanium metal piece with a cover glass glued by dental cement to seal the skin window for imaging.

For ex vivo measurement, skin samples were excised from the dorsal area of mice, which is the same as that in imaging in vivo. We removed the skin above the superficial fascia with a scalpel after depilation. The excised skin sample was approximately 15×10mm2, with a thickness of ∼400μm. Saline was added onto the sample when sealed between a cover glass and a glass slide to keep the skin moisturized. Transmittance measurement was performed immediately after sample preparation.

3. Results

3.1. Ex vivo transmittance measurement

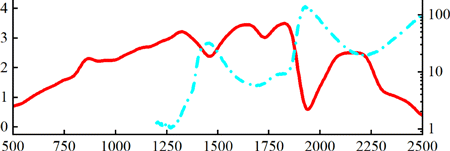

First, we measured the broadband transmittance of the freshly excised mouse skin. From the results we can clearly identify three windows with relatively high transmittance: 1300, 1700 and 2200nm windows (Fig. 2). For 1300, 1700 and 2200nm excitations, the measured transmittances are 3.18%, 3.18% and 2.48%, while the water absorption coefficients are 1.31, 5.80 and 19.69cm−1, respectively. These results are in agreement with previous MPM experiments excited at both the 1300 and 1700nm window. Although below the 1300nm window the transmittance decreases, we note that so far the most widely adopted excitation for skin MPM lies within the 800nm window, which can be conveniently excited by mode-locked Ti:Sa lasers. Besides, another key advantage is that excitation at the 800nm window enables two-photon fluorescence microscopy from endogenous fluorophores.

Fig. 2. (Color online) Measured transmittance of the freshly excised mouse skin from 500nm to 2500nm (transmittance, left ordinate, red line). Measured water absorption αA from 1200nm to 2500nm16 (absorption coefficient, right ordinate, blue dash-dotted line).

In order to qualitatively understand the existence of these three excitation windows, we also plotted water absorption spectrum from 1200nm to 2500nm (Fig. 2).16 We can see that the three excitation windows roughly overlap with the local minima in water absorption. Besides, strong water absorption around 1450 and 1925nm overlap with local minima in skin transmittance. The discrepancy in precise overlapping is due to the following: (1) Transmittance includes the overall contribution from skin absorption and scattering. (2) Skin absorption includes more than water absorption. In spite of this discrepancy, we can still conclude that for efficient transmittance through skin, the excitation wavelength should lie within a relatively low water absorption window. Consequently, the 2200nm window seems potentially advantageous for deep-skin MPM, judging from this transmittance measurement.

Ex vivo measurement as a useful guidance, cannot be equated with in vivo measurement in MPM. So next, we performed THG imaging of the mouse skin in vivo excited at both 2200 and 1700nm. The optical powers for both excitations on the skin surface were increased as imaging depth increased. For fair comparison, from 160μm below the skin surface to the deepest, we kept the maximum optical power on the sample the same (9mW) for both 2200 and 1700nm excitations.

3.2. Deep-skin THG imaging in vivo at 1700 and 2200nm window

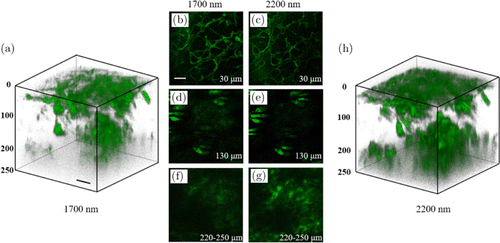

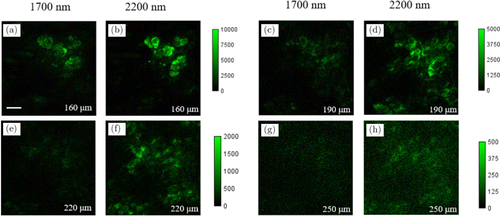

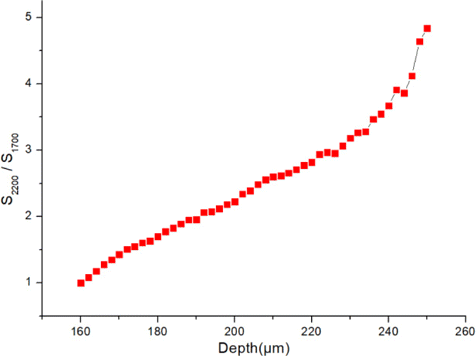

Figure 3 shows 3D stacks acquired with excitation at either 1700nm or 2200nm. Each image (including those in the 3D stacks) is individually enhanced in contrast with the same maximum pixel brightness. As imaging depth increases, both 1700 and 2200nm THG imaging results show similar skin structures of stratum corneum (Figs. 3(b) and 3(c)), sebaceous glands (Figs. 3(d) and 3(e)) and adipocytes (Figs. 3(f) and 3(g)). However, the most notable feature is that 2200nm THG images show deeper penetration into the skin than 1700nm: From 220μm to 250μm below the skin surface, adipocytes in 2200nm THG images can be clearly resolved. In sharp contrast, at similar imaging depths, they cannot be resolved in 1700nm THG images. These results show that with the same optical power on the skin surface, 2200nm excitation enables a larger penetration depth than 1700nm. The images with enhanced contrast in Fig. 3 cannot be used for direct THG signal comparison. In order to better illustrate the THG signal difference deep in the skin with both excitations, we excerpted THG images from acquired 3D stacks at the same imaging depth without enhancing the contrast. For each pair of images, the same color scale denoting the signal level was used for both excitations (Fig. 4). At z=160μm, both images show similar THG signals. However, as imaging depth increases, THG signals of 1700nm become lower than 2200nm THG images at the same depth. To quantitatively compare the THG signal decay with both excitations, we took the following procedure: (1) For images acquired below 160μm, in which both excitation powers on the sample were 9mW, we calculated the THG signals S2200 and S1700 of both excitations for each image. THG signals were calculated as mean values of the image. (2) Then we calculated the ratio S2200/S1700, normalized it at z=160μm and plotted it as a function of imaging depth z. The resultant ratio is shown in Fig. 5. As expected, the ratio increases with the increasing of z, which is in agreement with the imaging results. Besides, we also calculated the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) for Fig. 4, defined as the mean THG signal ratio between the maximum and minimum 1% pixels. The results summarized in Table 1 show that both THGs acquired at 2200nm show higher SBRs. We thus conclude that compared with 1700nm excitation, 2200nm excitation performs better in deep-skin MPM, and THG decays less as imaging depth increased at that window.

Fig. 3. THG images with 1700 (a), (b), (d), (f) and 2200 nm (c), (e), (g), (h) excitations. (a), (h) 3D-reconstructed stacks. (b)–(g) two-dimensional (2D) images from the stacks. The imaging depths below the skin surface were indicated in each 2D image. Each image is individually enhanced in contrast with a resultant maximum pixel brightness of 65,535. Scale bars: 50μm; pixel size: 512×512.

Fig. 4. THG images acquired with 1700nm (a), (c), (e), (g) and 2200nm excitation (b), (d), (f), (h), at different imaging depths below the skin surface as indicated in each image. Color scale denoting THG signal is the same for each image pair. Scale bars: 50μm; pixel size: 512×512.

Fig. 5. THG signal ratio S2200/S1700 as a function of imaging depth z. The ratio is normalized such that S2200/S1700=1 at z=160μm.

| Depths (μm) | 1700nm | 2200nm |

|---|---|---|

| 160 | 3968 | 8598 |

| 190 | 2071 | 3525 |

| 220 | 1021 | 1838 |

| 250 | 677 | 899 |

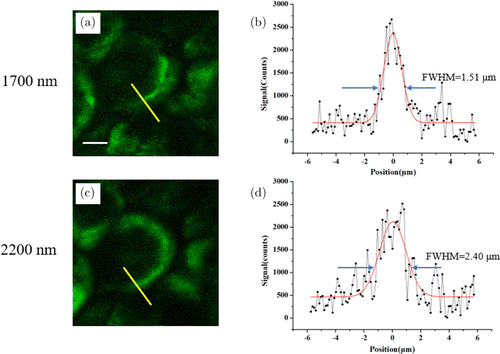

In order to characterize and compare spatial resolutions with both excitations, we imaged structures with the smallest lateral size, in our case the membrane of adipocytes, shown in Figs. 6(a) and 6(c). Then, we plotted line profiles along the adipocyte membrane (Figs. 6(b) and 6(d)). The full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of this line profile is a measure of the spatial resolution. The measured line profiles were fitted with Gaussian fitting, yielding FWHM values for both excitations. This whole procedure was repeated three times along different positions of the adipocyte. The measured FWHMs following this procedure are listed in Table 2. The mean FWHMs are 1.49μm for 1700nm and 2.40μm for 2200nm excitation, respectively. This lower spatial resolution of the 2200nm THG imaging is due to its longer wavelength.

Fig. 6. (Color online) THG image of adipocytes 170μm below the skin surface, excited at 1700nm (a) and 2200nm (c). The measured line profiles (black squares) along the yellow lines in (a) and (c) are shown in (b) and (d), respectively. The Gaussian fits (red curves) with measured FWHMs and are also indicated in (b) and (d). Scale bars: 10μm.

| Position | 1700nm (μm) | 2200nm (μm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.74 | 2.49 |

| 2 | 1.51 | 2.40 |

| 3 | 1.23 | 2.33 |

| Mean | 1.49 | 2.40 |

4. Discussion

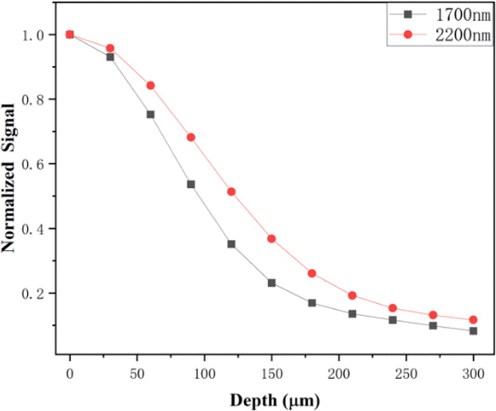

If we compare the ex vivo transmittance measurement and in vivo imaging results, we can readily see the discrepancy: Ex vivo measurement shows that higher transmittance favors the 1700nm window, rather than the 2200nm window; however, in vivo THG imaging shows the opposite: with the same optical power on the skin surface, 2200nm excitation images are deeper. We think this discrepancy may be due to the following: (1) Ex vivo biological sample is by no means is the same as in vivo sample. One example is that for deep-brain imaging in mouse, once the mouse dies, the imaging depth quickly drops given all other conditions are the same. This indicates that the nature of biological tissues may have changed before and after death. In order to test this hypothesis, we performed comparative THG imaging on mouse skin in vivo first, then we sacrificed the mouse and performed in the same area (which was essentially ex vivo imaging). The calculated signal ratio S2200/S1700 in Fig. 5, based on imaging, shows a similar behavior as imaging depth increases. This proves the vitality of the mouse cannot explain the deeper penetration of 2200nm. (2) So far, we have only compared excitation wavelengths. THG signals are also different: 567nm for 1700nm and 733nm for 2200nm, respectively. According to ex vivo measurement, transmittance at 733nm is higher than that at 567nm. For simplicity, if we assume that the skin is homogeneous, the effective attenuation length (le) is calculated to be 0.0957mm for 733nm and 0.0849mm for 567nm, respectively. If we assume that THG signals also decay exponentially in the skin, the normalized THG signal ratio S733nmS567nm=e−z/le(733nm)/e−z/le(567nm) will increase as imaging depth increases, partly explaining the deeper penetration of 2200nm THG imaging. We note that this emission wavelength explanation is similar to that in brain MPM.23 (3) Depth-dependent aberration is different between the two excitation wavelengths. Aberration is the accumulated phase from surface to the focus, and is inversely proportional to wavelength. Theoretically, after traversing the same tissue, longer wavelength accumulates less aberration than shorter excitation wavelength. It is well-known that the larger the aberration is, the poorer the multiphoton signal is. For example, in Ref. 24, we have shown that spherical aberration induced multiphoton signal degradation decreases as the excitation wavelength shifts from 850nm to 1300nm and 1700nm. Using the same theoretical model, we also calculated spherical aberration-induced multiphoton signal degradation at 2200nm and compared it to 1700nm. Our results in Fig. 7 indicate that as imaging depth increases, 1700nm suffers more from spherical aberration-induced multiphoton signal degradation compared with 2200nm. So, both emission wavelength difference and aberration may be the contributing factors for the deeper penetration of 2200nm excitation into the skin, compared to that of the 1700nm excitation.

Fig. 7. Spherical aberration-induced multiphoton signal degradation decreases as the depths increase, excited at 1700 and 2200nm.

5. Conclusions

In the previous work, we demonstrated the deep-brain imaging capability at the 2200nm window, but as for the imaging effectiveness or spatial resolution of 3PM, 1700nm window performed better.19 As is known to all, the skin is a multilayered structure, and thus, highly heterogenous imposing scattering and aberration onto the excitation light. Intuitively, low scattering and low aberration at 2200nm is more advantageous. In this paper, ex vivo broadband transmittance measurement clearly shows that the skin has a local maximum transmittance at this window. Furthermore, our in vivo THG imaging shows that with 9mW optical power on the skin surface, structures of 220μm below the skin surface can be resolved, and THG signals can still be generated at a depth of 250μm. So far, the maximum imaging depth is limited by the available optical power on the sample. We expect that this imaging depth can be further extended, given that higher optical power on the sample can be achieved by optimizing both the laser source and the overall transmittance of the imaging system. We also note that with 9mW optical power on the skin surface, we did not observe any structural damage to the skin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 61775143, 61975126 and 62075135); the Science and Technology Innovation Commission of Shenzhen under Nos. JCYJ20190808174819083, JCYJ20190808175 201640 and KQTD20150710165601017; and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M702241). Xinlin Chen and Yi Pan contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.