Optical neuroimaging of executive function impairments in food addiction

Abstract

This study investigated the neural mechanisms located in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) involved in maintaining addictive-like eating behavior. Therefore, we aimed to fill a gap in the existing literature and help clarify the food addiction (FA) cycle by inspecting the relationship between the executive control and psychopathology involved in the FA cycle. Twenty-three students recruited from the University of Macau participated in this study. We investigated a hemodynamic response captured by NIRS recordings, activated during -back, set-shifting, and go/no-go paradigms. Moreover, we investigated the FA symptoms through the YFAS clinical inventory to better understand the relationship between hemodynamic response and clinical symptomatology in college students. First, the hemodynamic findings confirm that altered cognitive control in executive function performance appears to be linked to addictive-like eating behaviors, which in turn confirms a circuit similarity between FA and the substance abuse population (SUD) as reported in previous fMRI studies. Secondly, the psychological findings confirm the significant association between the working memory deficits and symptoms severity which suggest the role of self-control and regulation in limiting the storage resources as a potential trigger to develop overconsumption episodes in the FA cycle. Our findings highlight how disrupted self-control and regulation of craving and negative affect induced by mental imagery might shape and overload the working memory storage as a potential trigger to develop binge eating episodes to maintain the FA cycle. In conclusion, the use of fNIRS in the context of eating disorders studies represents a valuable application, noninvasive, and patient-friendly tool, providing new insights into understanding the addiction cycle and treatment guidelines.

1. Introduction

Food addiction (FA) is conceptualized as a chronic disorder associated with impaired cognitive control circuits triggered by emotional and environmental conditions,1,2 which involves the neural systems associated with self-control, reward, and decision-making. To date, the distinctive and shared factors between FA and substance use disorders are yet to be fully understood.3,4 In addition, the impairment of executive functions (EFs) including working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition control is commonly detected in FA populations, which might also impede its treatment.

Interestingly, a recent study5 demonstrated that working memory exhibits limited resources to manage stress and anxiety responses, as well as to regulate craving and negative affect content. For example, a meta-analysis illustrated that altered working memory circuits in food cravers are linked to a locus of control disruption responsible for maintenance of addiction, mainly due to an impairment in visual-spatial sketchpad.5,6,7,8,9 In more detail, a previous behavior study has confirmed slower reaction times and distractions in working memory performance after exposure to mental imagery. Besides, although no neuroimaging studies have been conducted to verify the finding, no brain inspection has also been performed to investigate the mechanism associated with other cognitive control functions such as cognitive flexibility or inhibition control in FA. The existing evidence found with drug addiction patients suggests disrupted cognitive functions, including speed processing, visual-spatial attention, and cognitive flexibility,13,14,15 which negatively affects tasks’ performance. In particular, cognitive flexibility relies on the interconnected hub of brain networks,12 which integrates other EFs in a more extensive network including salience detection, attention, working memory, and inhibition to perform cognitive flexibility tasks successfully. As for inhibition control, neuroimaging findings15 conceptualize the neural basis of substance addiction as a pathology of motivation and choice, indicating that drug addiction patients have decreased dopamine release associated with reduced activation in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), which in turn reinforces the compulsive character of addictive behavior. More importantly, accumulating evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays an essential role in the cognitive process for behavioral addiction.4 Disrupted functions in the PFC can cause decreased motivation for healthy habits and potentiate dysfunctional behaviors such as weight gain in FA and drug overdose in substance abuse.3,4 Meanwhile, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), as a robust optical neuroimaging technique, is able to detect the hemodynamic response in the PFC with high sensitivity21 and concurrently monitor the neural activity in real-life conditions.22

Besides, the lack of optical neuroimaging studies investigating executive control impairments and psychopathology leads to an unclear understanding of how poor self-control and regulation skills might delay integrating emotional and motivational information in cognitive storage. Moreover, it remains unclear which particular cognitive resources are limited by the lack of self-control and regulation skills in FA. Consequently, the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS)11 was introduced to examine the relationship between impaired cognitive control circuits and general psychopathology comorbid with a FA disorder. The tool assesses seven FA symptoms, as well as clinically significant impairment or distress. The YFAS is composed of 25 questionnaire items used to access diagnostic criteria for food addiction, which translates the diagnostic criteria for substance dependence outlined in the DSM-V. Concerning the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM-V) substance dependence criteria 7, YFAS is a valid psychometric tool to diagnose FA “that translates the substance-dependence diagnostic criteria to apply to the consumption of highly palatable foods.” Higher scores on the YFAS have been linked to increased impulsivity, more frequent binge-eating episodes, higher scores of depression, negative effect, craving, reduced weight loss during the treatment and increased weight in response to bariatric surgery. Importantly, the core symptomatology reveals a strong link between poor self-control and regulation skills and affective psychopathology, such as the emotional dysregulation, depressive and anxiety symptoms that trigger a craving, and binge-eating episodes.11

Therefore, the aim of this work relies on (i) the use of fNIRS optical neuroimaging technique to systematically inspect the neural substrates underlying EF impairments associated with FA; (ii) additionally, to examine the relationship between self-control/regulation and FA, in particular, the association between higher and lower symptoms in FA behavior with specific executive control impairments. It was expected that the FA group would have a significant brain activation difference in the PFC as compared to normal controls. It was expected as well that significant psychological symptoms from the FA group might be identified, which are linked to executive control impairments.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited through advertisement flyers shared on the university campus, while the data collection was conducted in the bioimaging core lab located in the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Macau. Inclusion criteria included: (a) 20–35 years, (b) right-handed, (c) corrected-to-normal or normal vision, while the exclusion criteria included: (a) no history of psychiatric or neurological disorders, and (b) no history of alcohol or substance abuse. Altogether, 23 college students ranging in age from 23 to 32 (14 females, 9 males, mean age = 27.5 years, S.D. = 9.37) participated in this study. Their psychological symptoms were assessed using both the self-reported measure-Yale Food Addiction Scale 24 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V) criteria for FA disorders seven days before the scanning day. The diagnostic threshold measure relies on the presence of more than 3 (of 7) addiction symptoms experienced in the past 12 months. To confirm the severity of the FA symptoms, a clinical interview was performed through the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V) criteria by a licensed clinical psychologist. All participants signed informed consent forms prior to the experiment, and the Clinical Ethics Committee approved the protocol for the present study of the University of Macau. The demographic characteristics are given in Table 1.

| college students n = 23 | |

|---|---|

| Age (M, SD)a | 27.5 (9.37) |

| Gender (female) | 14 females |

| Gender (male) | 9 males |

| Education (graduate)b | 50% |

| Education (undergraduate)b | 50% |

2.2. Experimental materials

To optimize the ecological validity of the present tests, the experimental materials were carefully chosen from the free royalty database (iStock (istockphoto.com)). The selected food pictures needed to meet three requirements: colorful, white background, and centered. In addition, highly palatable food and beverages were cheeseburgers, French fries, chocolate bagels, Coca-Cola, and Sprite, while healthy food and beverages were vegetables, fruits, water, and milk.

2.3. Paradigm and procedures

fNIRS neuroimaging was carried out in this work. Each participant had to perform three EF tasks in a block design (-back for working memory, the set-shifting task for cognitive flexibility, and the go/no-go task for inhibition control). Each trial of the functions was visually presented with a junk or healthy food-based picture.

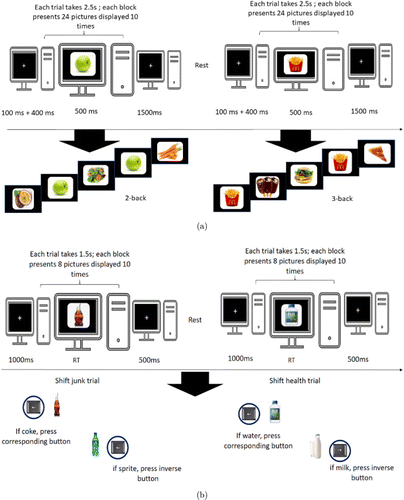

For the 2- or 3-back task, participants were required to judge if the picture was the same as the previous third or fourth one. -back task (Fig. 1(a)) was acquired in 10 sections. Each section had two blocks (2-back and 3-back) with four conditions: 2-back healthy, 2-back junk, 3-back healthy, and 3-back junk. Therefore, each 2-back or 3-back condition included two categories of stimuli materials: junk or healthy items (e.g., foods and beverages). Altogether, each block contained 24 trials, and each trial lasted 2.5s. The duration of each block was 1min, and each block was repeated 10 times, whereas the duration of each task was 20min. Data from the shifting task (Fig. 1(b)) were collected in 10 blocks. Each block had two conditions (shift junk and shift healthy), in which junk or healthy respectively represented the categories of food or beverages. Each condition consisted of eight trials, and each trial lasted 1.5s. Therefore, it took 4min to complete the shifting task. In addition, the go/no-go task (Fig. 1(c)) had 10 blocks, and each block had four conditions (go health, no-go healthy, go-junk, and no-go junk), in which each condition consisted of 12 trials, and each trial lasted 2.5s. The conditions from the three tasks were administered randomly. Besides, an infinite time (rest time) was introduced in the middle of the tasks defined by the subject.

Fig. 1. The schematic paradigm for fNIRS data acquisition: (a) -back, (b) set-shifting, and (c) go/no-go experimental tasks.

2.4. fNIRS data acquisition

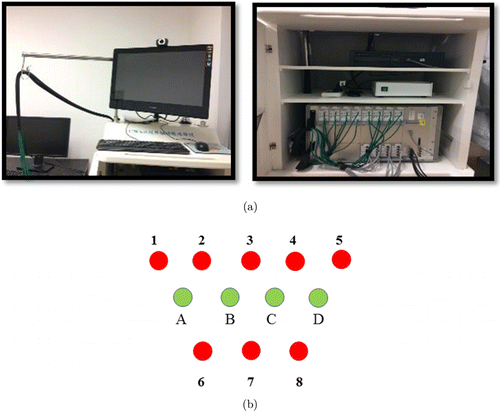

An early continuous-wave (CW) fNIRS system (CW6 system; TechEn, Milford MA) with a total of four laser sources and eight optical detectors was utilized for the present data collection (Fig. 2(a)).17,18 Two lights with wavelengths of 690 nm and 830 nm were emitted at each source fiber, which provides accurate detection for the changes of both HbO and HbR concentrations at a sampling rate of 50Hz.19 The four emitters and eight detectors were connected through a custom-built patch to generate 14 channels, comfortably covering the participant’s PFC (Fig. 2(b)). The distance between each laser source and each detector was 3cm. After the experimental task, a 3D digitizer (Patriot, Polhemus, Colchester, Vermont, USA) was used to measure the 3D Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates of each optode or each channel. Next, averaged 3D coordinates were imported to NIRS-SPM for spatial registration to generate the Brodmann areas and respective MNI coordinates (see Table 2).

| Channels | Broadmann area | MNI (x,y,z) |

|---|---|---|

| CH_1 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 46) | 33 67 4 |

| CH_2 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 46) | 22 72 6 |

| CH_3 | Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 47) | 9 74 7 |

| CH_4 | Frontopolar area (BA 10) | 44 52 26 |

| CH_5 | Frontopolar area (BA 10) | 32 58 27 |

| CH_6 | Orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex (BA 10) | 19 65 29 |

| CH_7 | Orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex (BA 10) | −10 67 29 |

| CH_8 | Frontopolar area (BA 10) | −8 73 7 |

| CH_9 | Frontopolar area (BA 10) | −19 72 7 |

| CH_10 | Frontopolar area (BA 10) | −31 66 5 |

| CH_11 | Orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex (BA 10) | −7 66 30 |

| CH_12 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 46) | −18 65 27 |

| CH_13 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 46) | −29 59 26 |

| CH_14 | Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 47) | −39 53 25 |

Fig. 2. The figure illustrates: (a) CW6 continuous wave system (Techen); (b) patch configuration for sources (green) and detectors (red).

2.5. Data analysis

fNIRS data were preprocessed using the HOMER 2 software (http://homer-fnirs.org/). The preprocessing stage relies on the following: (i) The conversion of optical density measurements to the concentration changes of HbO and HbR at different time points.17,18 (ii) Secondly, the raw hemoglobin continuous data were processed by a high cut-off filter of 0.01Hz and subsequently a low cut-off filter of 0.1Hz; (iii) Third, after data preprocessing, we then examined the HbO concentration differences between the different conditions. Finally, we inspected the HbO data for each channel between various conditions with repeated measures ANOVA, and the brain activation maps were visualized by BrainNet Viewer http://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/.20 Further, Pearson correlation analysis was carried out between the YFAS scores and HbO data. The statistical analyses were performed by IBM SPSS Statistics software, and the -value was corrected according to Greenhouse–Geisser.

3. Results

3.1. Hemodynamic study

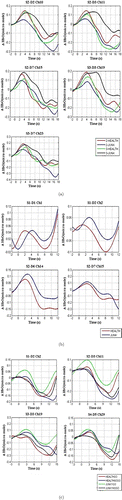

Grand-average concentration changes in oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) were acquired for each channel from the three tasks (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Hemodynamic average changes. The mean concentration changes of HbO for all channels during the -back task (a), set-shifting (b), and go/no-go tasks (c). The unit of the -axis is a micro-mole, and the -axis denotes the time point(s). (a) -back task: The red color represents 2-health, the blue color represents 2-junk, the green illustrates 3-health while the black color represents the 3-junk condition; (b) Set-shifting task: The blue color illustrates the shift junk, while the red represents the shift healthy condition. (c) go/no-go task: The red color represents healthy go, the blue demonstrates the healthy no-go, the green illustrates junk go, while the black color represents the junk no-go condition.

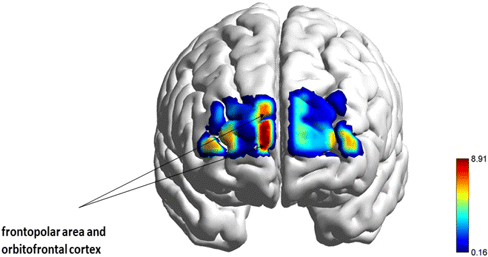

3.1.1. Working memory performance

A 2 (food type: healthy and junk) × 2 (working memory levels: 2-back and 3-back) × 14 (number of channels) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted. All three factors were within-subject factors. No main effect of food type, working memory levels, and channels was identified (p > 0.05). However, a three-way interaction among working memory levels, food type, and channels was found: F(2,44) = 6706, p < 0.005 (see Fig. 5). Subsequent post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that channel 4 in the 3-back junk condition elicited a higher hemodynamic response than the 3-back healthy condition: t(22) = −2089, p < 0.048; channel 5 in the 3-back junk condition gave higher HbO than the 2-back junk condition: t(22) = −2191, p < 0.039; channel 7 presented a higher hemodynamic response in the 3-back junk condition than in the 3-back healthy condition (t(22) = −2600, p < 0.016) and in the 3-back healthy compared to 2-back healthy condition (t(22) = 3099, p < 0.005); increased HbO was also identified in channel 8, with 3-back junk higher than 2-back junk (t(22) = −3823, p < 0.001) and 3-back junk higher than 3-back healthy (t(22) = −4494, p < 0.000); channel 10 also revealed an increased hemodynamic response with 3-back junk higher than 3-back healthy (t(22) = −2732, p < 0.012) and 3-back junk higher than 2-back junk (t(22) = −2286, p < 0.032).

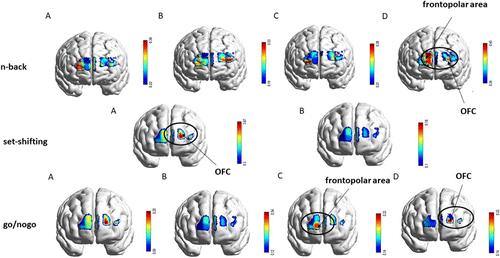

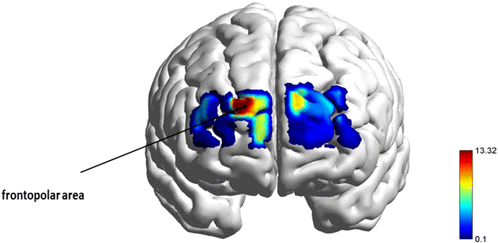

Fig. 4. Brain activation differences (oxy-hemoglobin effect size; -value) generated for the three tasks (-back, set-shifting and go/no-go). For the -back task, the brain activation maps represent (a) 2-back healthy, (b) 2-back junk; (c) 3-back healthy, (d) 3-back junk; for the set-shifting task, the brain activation maps illustrate: (a) shifting junk, (b) shifting healthy; for the go/no-go task, the brain activation maps represent: (a) healthy go, (b) healthy no-go; (c) junk go; (d) junk no-go. The black circle highlights the brain activation in significant experimental conditions (p ≤ 0.05)

Fig. 5. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of workload x food type x channels interaction in the n-back task. The figure illustrates the F-statistical maps thresholded at p ≤ 0.05.

3.1.2. Shifting performance

A 2 (shift/food type: healthy and junk) ×14 (number of channels) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted. All three factors were within-subject factors. A main effect of shift/food type (F = 13.085, p < 0.01) and channels (F = 3.827, p < 0.05) were identified (see Figs. 4 and 6). Junk food elicited a higher hemodynamic response than healthy food.

Fig. 6. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of food type and channels in the set-shifting task. The figure illustrates the F-statistical images thresholded at p ≤ 0.05.

3.1.3. Inhibition performance

A 2 (food type: healthy and junk) ×2 (go/no-go levels: go and no-go) ×14 (number of channels) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted. All three factors were within-subject factors. A main effect of channels was identified (F(1,13) = 4509, p < 0.05), and main effect between go/no-go levels and channels was also found: F(1,13) = 3182, p < 0.05 (see Fig. 7). Subsequent post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that in channel 2, the junk no-go condition had a higher hemodynamic response than the healthy go condition: t(22) = −2726, p = 0.048m, and junk no-go presented an increased HbO compared to healthy no-go: t(22) = −2.164, p = 0.042; in channel 5, the junk no-go condition exhibited higher HbO than the junk go condition: t(22) = 3.650, p < 0.001; in channel 8, the junk go presented a higher hemodynamic response compared to healthy no-go: t(22) = −2.682, p = 0.014; an increased hemodynamic response was also detected in channel 13, with junk go higher than the healthy no-go condition (t(22) = −2.546, p = 0.018), junk no-go higher than healthy go (t(22) = −2.548, p = 0.018), and junk go higher than healthy go (t(22) = −3.531, p = 0.002).

Fig. 7. A repeated measures ANOVA computed for go/no-go task. (a) revealed a main effect of channels, while (b) illustrates the main effect of channels go/no-go levels interaction. Both F-statistical maps were thresholded at p ≤ 0.05.

3.2. Brain imaging study

3.2.1. Mapping brain activation for working memory performance

In the 2-back healthy condition, higher cortical activation was detected in the right dorsolateral cortex involved in executive functions, decision-making, and cognitive control; orbitofrontal and left dorsolateral areas were activated for 2-back junk conditions to recruit decision-making process, emotional regulation skills, and reward system. A similar pattern was found between 3-back healthy and 2-back healthy conditions based on the higher activation in the right dorsolateral cortex; finally, 3-back junk (Fig. 5, p < 0.05) elicited higher activation in the frontopolar area which is responsible for short-term memory storage and visual-spatial processing (Fig. 4; -back; (a), (b), (c), (d)).

3.2.2. Mapping brain activation for shifting performance

In the junk shift condition, higher activation was detected in the dorsolateral cortex (BA 46), specifically involved in executive functions, planning, decision-making, and cognitive control; as well as in the OFC (BA 10/BA 11), responsible for the recruitment of working memory (BA10), decision-making process, emotional regulation, and reward system (BA11) (Fig. 6, p < 0.05). By contrast, health shift conditions have shown reduced activation compared to junk shift conditions (Fig. 4; set-shifting; (a), (b)).

3.2.3. Mapping brain activation for inhibition performance

In the healthy go condition, higher activation was detected in the left medial frontal cortex involved in working memory, attention, and planning, and the ventral medial cortex specialized in attention control and sequential processing. By contrast, the healthy no-go condition did not present increased activation compared to all three conditions. Frontopolar area activation was found in the junk go condition, responsible for working memory skills, and multi-tasking coordination (Fig. 7(a), p < 0.05). Finally, junk no-go (Fig. 7(b), p < 0.05) elicited higher activation in the medial frontal cortex and ventromedial cortex during the coordination of higher-order cognitive skills, such as cognitive self-regulation, inhibition process, working memory, decision-making process, and selective attention (Fig. 4; go/no-go; (a), (b), (c), (d)).

3.3. Screening, diagnostic, and clinical assessment

3.3.1. Establishing thresholds for diagnostic criteria on the YFAS

In the diagnostic version, which represents diagnosis of substance dependence, criteria were considered to be met if participants endorsed three or more criteria and at least one of the two clinical significance items (impairment or distress). The symptom count score was based on the sum of the seven diagnostic criteria.

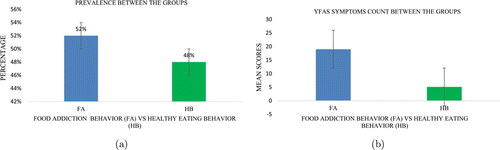

3.4. Prevalence and YFAS symptoms count score between the groups

The FA prevalence (A) and the mean scores of the symptoms count score between the groups (B) are shown in Fig. 8. The prevalence for those who met the threshold for FAwas higher (52%) and lower for those who did not meet healthy eating behavior criteria (48%). Considering the YFAS diagnostic version,11 the symptoms count score between the groups demonstrated a higher mean in the FA Behavior group (M = 19; SD = 7.45) and a lower mean in the Healthy Eating Behavior group (M = 5.09; SD = 3.14).

Fig. 8. Prevalence (a) and YFAS Symptoms count score (b) between the groups: FA Behavior and Healthy Eating Behavior (HB) groups. The error bars were calculated based on the standard error, and the analysis unit represents the percentage and YFAS mean scores, respectively.

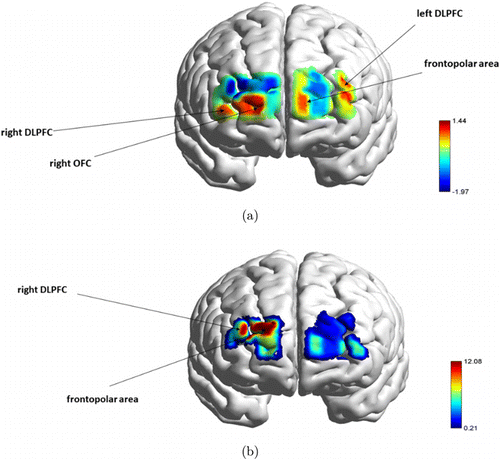

3.5. Association between YFAS data and [oxy-Hb] data

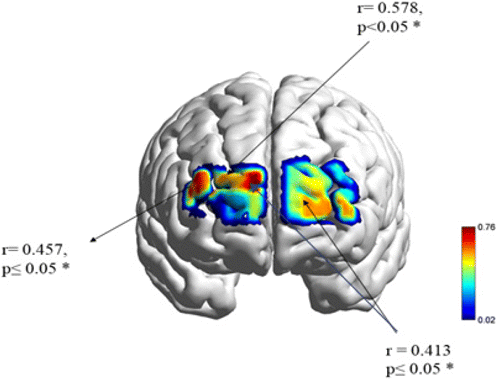

Pearson correlation analysis found significant differences between the [oxy-Hb] activity and FA symptoms. Higher activation of [oxy-Hb] in 2-back healthy was positively related to lower scores in the healthy eating behavior group (less than three symptoms). In comparison, increased activation during the 3-back workload (junk and healthy conditions) was negatively correlated with higher scores in the FA behavior group (equal to three symptoms) (see Table 3 and Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. The map illustrates the brain regions involved in the relationship between the working memory performance and symptoms severity in YFAS, p ≤ 0.05*.

| n = 23 | Right DLPFCc2-back health[oxy-Hb] | Frontopolard3-back junk[oxy-Hb] | Right DLPFCd3-back health[oxy-Hb] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| College students — healthy eating behaviora | 11 | r = 0.578* | ||

| College students — food addiction behaviorb | 12 | r = 0.413* | r = 0.457* |

4. Discussion

The current fNIRS study confirms the involvement of executive impairment in the PFC to explain the FA cycle. Twenty-three graduates and undergraduate college students were recruited from the University of Macau to participate in this study.

First, the hemodynamic findings confirm that altered cognitive control in executive function performance appears to be linked to addictive-like eating behaviors in Macau college students, confirming a circuit similarity between FA and the substance abuse population (SUD) as reported in previous fMRI studies. Second, the psychological findings confirm the significant association between the variables demonstrating the role of distorted cognitive and emotional information in working memory storage as a potential trigger to develop FA behavior.

In the first hypothesis, our findings propose altered hemodynamic changes in the middle frontal gyrus (BA 46), frontopolar (BA 10), and OFC (BA 10, 11, 47) during the 3-back junk activation compared to 3-back healthy and 2-back junk conditions for working memory performance. In the shifting performance, altered activation was detected in the left dorsolateral PFC (BA 46) and the left OFC (BA 11, BA 10) when the junk shift condition was activated, compared to the healthy condition. Finally, increased hemodynamic recruitment was identified in the frontopolar area (BA 10) elicited for the junk go condition, in the medial frontal gyrus (BA 46), ventrolateral (BA 45), and dorsolateral (BA 46) for the junk no-go conditions compared to healthy conditions (healthy go and healthy no-go). Consistent with working memory impairment, the hemodynamic findings confirm altered cognitive flexibility and inhibition performance in the college student sample. Concerning the impaired cognitive flexibility performance, the left OFC cortex (BA 10) and left VLPFC (BA 45) are involved when the shifting mechanism is recruited to deal with highly palatable items, compared with neutral and healthy food items. The findings are consistent with the fMRI study,14 showing that decreased activation in the OFC and DLPFC are associated with cognitive inflexibility, as observed in obsessive-compulsive disorder or addiction. As expected, the evidence confirms the critical role of the DLPFC and OFC linked to cognitive rigidity in FA behaviors. Finally, our findings suggest that inhibition performance is associated with a higher hemodynamic response and significant activation in the junk go and junk no-go conditions than healthy conditions. More specifically, highly palatable items displayed during the junk go block were first available in the task sequence, which might influence and generate higher activation of superior and inferior frontopolar regions. Besides recruiting vascular resources at the inhibition stage,4 a higher hemodynamic response seems to be recruited when higher-order cognitive skills (such as planning, decision-making, and attentional control) are recruited to select highly palatable food. This evidence is consistent with fMRI research that has reported significant reductions in D2 receptor availability in the striatum, linked to decreased metabolism in the PFC regions involved in salience attribution, inhibitory control, emotion regulation, and decision-making.3,4

Furthermore, the inhibition process captured during the junk no-go conditions might be anticipated by a planning and decision-making process that fails when the long-term consequences of actions are not adequately evaluated. Relying on this evidence, the vascular sensitivity found during junk go performance might reflect the challenged evaluation required by the decision-making process. The assumption seems to be in line with recent research conducted by Verdejo-Garcia and colleagues13,14 that connects stages of inhibition related to failure with the decision-making process.

Concerning the psychological study and second hypothesis, 12 college students met the YFAS criteria for the FA group confirmed through the clinical interview guided by DSM-V criteria. In comparison, 11 students met the criteria for the healthy eating behavior group (lower than three symptoms). The second hypothesis confirms the expectation that the college students in the healthy eating behavior group (lower than three addiction symptoms) were positively associated with the 2-back workload in healthy conditions. In more detail, nonoverloaded working memory performance when viewing healthy food pictures was found to be associated with the control group. Besides, the consumption of highly palatable food, frequent binge-eating episodes, increased negative affect and depression, higher rates of craving, or reduced weight loss assessed by YFAS were found to be negatively associated with altered cognitive control during the working memory performance in the FA group. In more detail, the additional vascular resources recruited during 3-back junk and 3-back healthy performance were found to be negatively correlated with college students in the FA group (higher than three addiction symptoms). In this sense, the finding proposes that the increase of hemodynamic response underlying the impaired recall interval activated for any food item (either highly palatable or neutral) might reflect poor self-control skills to cope with craving, hedonic eating, and stressful eating-related events, having a higher likelihood of developing the disorder. Also, when a subject engages in hedonic eating cycles, she/he seems to adopt overconsumption patterns for the pleasure of eating food, either junk or healthy food. According to the previous research work about working memory dysfunction,5 cue-exposure or mental imagery disrupts operating memory performance since it limits the existing cognitive resources. Besides, it leads to distraction rather than speedy detection. Another perspective to untangle the relationship between working memory, cognitive control, and failure in decision-making suggests that altered working memory performance detected in the frontopolar area during the 3-back condition and in the left orbitofrontal/left dorsolateral cortex during the 2-back condition seems to reflect a compensatory mechanism. Additional recruitment of vascular resources is required to cope with high cognitive demand and consequent arousal generated by highly palatable food. Importantly, significant hemodynamic changes inferred by cortical activation (Figs. 3 and 4) are consistent with the working memory findings proposed by previous research.5,6

Furthermore, according to the review,5 the impaired recall of highly calorific food is related to distorted experiences and memories stored, triggering the impulsive decision-making pattern. Besides, as supported by recent research work,22 the authors highlight the working memory overload associated with poor management of craving episodes, also described by students with FA behavior during the clinical interview. Once the working memory is overloaded with highly calorific images and hedonic food images in general, it becomes harder for them to keep up the required cognitive control and make a decision based on long-term benefits. Additionally, in line with previous research linking affective regulation and working memory performance,5 our findings also confirm the relevant association between the variables demonstrating the role of negative affect and distorted emotional information in the working memory storage as a potential trigger to develop FA behavior. In more detail, the dysfunctional affect regulation consistently demonstrated by YFAS items was clarified by a clinical interview with both groups and pointed out by the FA behavior group as a trigger to develop craving episodes and compensatory hedonic experiences to manage negative emotions and stressful events. Based on their reports, poor management of negative affect and stressful events is crucial in generating mental imagery and working memory overload, leading to a failure in the decision-making process. By contrast, shifting and inhibition performances were not correlated with the clinical scores obtained in YFAS.

Finally, concerning the altered hemodynamic response and psychological symptoms, we suggest that the additional vascular resources and the consequent increase of network response are recruited to process highly palatable conditions and higher workload executive conditions, reflecting a decrease of cognitive control in prefrontal circuits and slower behavioral responses, such as the lack of self-control skills to regulate craving, strong negative emotions, and stressful eating-related events.

Regarding the study limitations, hemodynamic and psychological studies in FA behavior should be conducted with larger clinical populations. Besides the focus on the college students’ sample, it would be highly relevant to expand to other local community groups in Macau. Moreover, there is an urgent need to combine neuroimaging methodologies with brain stimulation techniques to enhance cognitive control responsible for the FA cycle (such as neurofeedback, tDCS, TMS). Another relevant concern relies on the lack of connectivity studies exploring the connectome irregularities and impaired neurocircuitry dynamics in FA; exploring additional directions through connectivity studies will expand the understanding behind FA behavior. Finally, a design investigating the differences in hemodynamic response between the FA and control group should be considered as a future research direction, which offers a comprehensive strategy to complement the current findings.

However, the strength s and implications of the fNIRS-YFAS method applied to FA merge three directions: methodological, theoretical, and therapeutical. Most nonmedical interventions applied to FA and eating disorders, such as clinical psychology and cognitive rehabilitation, rely on psychological and behavioral self-reported instruments, an inspection of DSM-V criteria, and standardized clinical interviews. Due to the limitations in classical clinical settings and lack of depth during the evaluation process, mental health science is challenged to design and validate novel solutions for assessment and intervention. Therefore, this study provided a reliable noninvasive methodological solution (fNIRS) combined with a validated clinical inventory (YFAS) to propose a deep inspection strategy that does not neglect the executive and affective-behavior neural mechanisms that are critical to the maintenance and treatment of the FA cycle. Second, the combined method confirms the shared neural correlates between FA and SUD proposed by the existing literature3,4; however, it provides a distinctive lens into the FA cycle by discovering that higher symptoms in YFAS such as a lack of self -control and regulation abilities are correlated with high-load working memory circuits, but not with cognitive flexibility and inhibition circuits. The evidence in the FA group compared to healthy eating behavior provided support to the therapeutical implications, which highlight the specific role of working memory associated with self-control and regulation mechanisms to the treatment of the FA cycle. In conclusion, the use of fNIRS represents a valuable application in addiction disorders, a noninvasive and patient-friendly tool, providing reliable insights into the understanding of the addiction cycle and new treatment guidelines.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the grant support provided for the Macau government (FDCT — Fundo para o Desenvolvimento das Ciencias e da Tecnologia) and the University of Macau (FHS — Faculty of Health Sciences). This study was supported by FDCT 025/2015/A1 grants from the Macao government and by research grants MYRG2014-00093-FHS, MYRG 2015-00036-FHS from the University of Macau.