Orthogonal Aza-BODIPY–BODIPY dyad as heavy-atom free photosensitizer for photo-initiated antibacterial therapy

Abstract

Photodynamic antibacterial therapy shows great potential in bacterial infection and the reactive oxygen species (ROS) production of the photosensitizers is crucial for the therapeutic effect. Introducing heavy atoms is a common strategy to enhance photodynamic performance, while dark toxicity can be induced to impede further clinical application. Herein, a novel halogen-free photosensitizer Aza-BODIPY-BODIPY dyad NDB with an orthogonal molecular configuration was synthesized for photodynamic antibacterial therapy. The absorption and emission peaks of NDB photosensitizer in toluene were observed at 703nm and 744nm, respectively. The fluorescence (FL) lifetime was measured to be 2.8ns in toluene. Under 730 nm laser illumination, the ROS generation capability of NDB was 3-fold higher than that of the commercial ICG. After nanoprecipitation, NDB NPs presented the advantages of high photothermal conversion efficiency (39.1%), good photostability, and excellent biocompatibility. More importantly, in vitro antibacterial assay confirmed that the ROS and the heat generated by NDB NPs could extirpate methicillin-resistant S. aureus effectively upon exposure to 730nm laser, suggesting the potential application of NDB NPs in photo-initiated antibacterial therapy.

1. Introduction

Bacterial infectious disease, a worldwide public health issue, is greatly alleviated because of the emergence of antibiotics.1,2,3 Unfortunately, with the long-term usage of antibiotics, the bacteria tend to develop resistance.4,5,6 The occurrence of the drug-resistant stain cycle is much faster than the development of antibiotics, making infectious diseases more challenging.7,8 In the mid-1990s, photodynamic antibacterial therapy as an alternative antimicrobial method has been used for bacteria inactivation.9 Photodynamic antibacterial therapy exhibits a robust antibacterial activity towards drug-resistant bacteria without the emergence of new drug resistance.10,11,12,13 More importantly, compared with traditional antibiotics, photodynamic antibacterial therapy possesses strong biofilm removal capability.14,15,16,17 For photodynamic antibacterial therapy, bacteria cells are killed by the reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the photosensitizers receiving appropriate photoirradiation.18 It is undeniable that the development of photosensitizer with high ROS generation performance and low biotoxicity is a critical issue for photodynamic antibacterial therapy.19 Currently, many porphyrin photosensitizers, such as Protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) and Hemoporfin, have been approved and employed for clinical treatment.20,21 However, the shortcomings of low molar extinction coefficient, poor photostability, and relatively short absorption maxima for those porphyrin photosensitizers, limiting their applications in the biomedical field to some extent.22,23

Recently, Aza-boron-dipyrromethene (Aza-BODIPY) derivatives have attracted great research interest as photosensitizers owing to the advantages of high molar extinction coefficient, high photostability, tunable photophysical property, facile synthesis, high phototoxicity/dark toxicity ratio, and red-shifted absorption/emission spectra.11,18,24 Under the near-infrared light excitation, the singlet excited state (S1)1) of photosensitizers can be populated to the triplet excited state (T1) through the intersystem crossing (ISC). The triplet excited photosensitizers can produce ROS for photodynamic antibacterial therapy through energy and/or electron transfer.25,26 For example, the Aza-BODIPY photosensitizers modified with phenothiazine, diphenylaniline, or bromine and ammonium salt simultaneously, achieved good antibacterial effects against S. aureus, E. coli, and C. albicans.11,27 The introduction of halogen atoms such as bromine and iodine onto the Aza-BODIPY unit is beneficial to intersystem crossing, resulting in a high ROS production and a satisfactory bactericidal and antitumor performance.28,29,30 However, the halogen modification of photosensitizers also results in certain dark toxicity, further impeding the clinical application.31 To overcome this issue, many scientists adopt the molecular configuration tuning strategy to improve ROS production efficiency.32,33

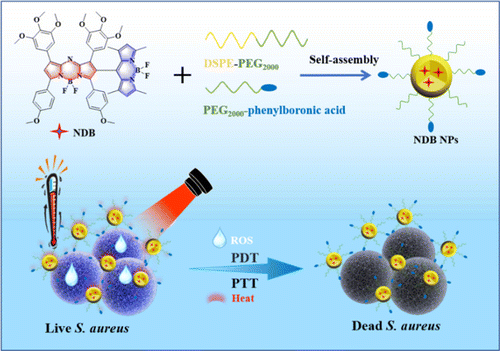

Herein, a heavy-atom-free Aza-BODIPY derivative NDB with high ROS production and near-infrared absorption has been synthesized for photodynamic antibacterial therapy. Based on the spin-orbit charge transfer intersystem crossing (SOCT-ISC) mechanism, BODIPY moiety was incorporated onto the Aza-BODIPY unit to construct an orthogonal dyad to promote the ROS generation.34 The photophysical, electrochemical, and photodynamic properties of NDB were characterized in detail. PEGylated phenylboronic acid was used for the encapsulation of NDB via the nanoprecipitation method to achieve the hydrophily of NDB. The obtained NDB nanoparticles (NPs) demonstrated satisfactory bactericidal performance, excellent photostability, and superior biocompatibility (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. The preparation of NDB NPs and their application in antibacterial phototherapy.

2. Materials and Measurements

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) ATCC43300 was obtained from the Chinese General Microbiological Culture Collection Center. BeyoPureTM LB Broth and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All chemical reagents were bought and used directly. The photophysical properties were explored via UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer and fluorescence (FL) spectrophotometer. The nanoparticle diameter and morphology were characterized via dynamic light scattering instrument and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The FL images were obtained via Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. The temperature change of the samples was measured using a NIR thermal imaging device. The electrochemical property was analyzed using a CHI 620C electrochemical analyzer with a three-electrode one-compartment cell.35 Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker Autoflex speed MALDI-TOF Mass spectrometer. Elemental analysis of C, H, N, and S was performed on a Vario EL III microanalyzer.

2.1. Synthesis of compound 5

Compound 4 was synthesized according to the literature,36 and the detailed synthesis process was described in the supplementary information. Compound 4 (0.22g, 0.30mmol) and anhydrous dimethylformamide (3mL) were added into anhydrous dichloromethane (10mL) in a 50mL round bottom flask. After bubbling nitrogen into the solution to remove the oxygen, phosphorus oxychloride (3mL) was injected slowly at 0∘C and stirred. Subsequently, the resulted mixture was heated to 70∘C and stirred for 3h. After cooling to room temperature, 200mL of aqueous potassium carbonate solution (10%) was added to quench the reaction. The resulted solution was further extracted with dichloromethane (30mL×3), and the organic layer was collected and washed with water. After removing the solvent by rotary evaporator, the product was further purified by column chromatography (petroleum ether/dichloromethane = 1:2), and compound 5 was obtained as a solid (0.19g, 82%). 1H NMR (400MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm)=9.74 (s, 1H, Ar–CHO), 8.17 (d, J=8.0Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.69 (d, J=8.0Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.22 (s, 2H, Ar–H), 7.19 (s, 1H, Ar–H), 7.08 (s, 2H, OCH3), 7.04–7.01 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 3.95 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.92 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.90 (d, J=4Hz, 6H, OCH3), 3.78 (s, 6H, OCH3), 3.69 (s, 6H, OCH3). Elemental Anal. Calcd for C41H38BF2N3O9: C, 64.32; H, 5.00; N, 5.49; Found: C, 64.40; H, 4.97; N, 5.43.

2.2. Synthesis of compound 6

Compound 5 (76.60mg, 0.1mmol) was dissolved in 2, 4-dimethylpyrrole (0.20mL, 1.60mmol). Under the protection of nitrogen, trifluoroacetic acid (20 μL, 0.24mmol) was injected. After 30min, sodium hydroxide aqueous solution (30mL, 0.20M) was added to quench the reaction. The obtained solution was washed with saturated sodium chloride and extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layer was collected and concentrated by rotary steaming. Next, the crude product was purified through the flash column to obtain the intermediate compound 6, which was directly used without further purification.

2.3. Synthesis of NDB

Compound 6 was dissolved in 20mL of dichloromethane, tetrachlorobenzoquinone (73mg, 0.30mmol), triethylamine (1mL) and boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (3mL, 24.30mmol) were added in sequence and reacted for 60min. Then, the reaction solution was concentrated directly by using rotary evaporator, and washed with saturated sodium chloride and extracted with dichloromethane. Through purification with flash column (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 1:1), the final product NDB was obtained as purple solid (11mg, 11.2%). 1H NMR (400MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm)=8.11 (d, J=9.2Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.64 (d, J=8.8Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.24 (s, 2H, Ar–H), 7.09 (s, 1H, pyrrole-H), 7.05 (d, J=8.4Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 6.99 (s, 2H, Ar–H), 6.85 (d, J=9.2Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 5.96 (s, 2H, Ar–H), 3.93 (s, 3H, Ar–CH3), 3.89 (s, 3H, Ar–CH3), 3.85 (s, 3H, Ar–CH3), 3.79 (s, 3H, Ar–CH3), 3.74 (s, 6H, OCH3), 3.46 (s, 6H, OCH3), 2.50 (s, 6H, OCH3), 2.00 (s, 6H, OCH3). 13C NMR (100MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm)=162.86, 161.07, 155.89, 153.26, 152.86, 141.97, 132.20, 130.99, 127.36, 127.04, 123.17, 121.48, 114.49, 113.93, 106.95, 106.71, 61.05, 56.03, 55.31, 29.68, 14.61. MALDI-TOF (m/z): calcd for C53H51B2F4N5O8 [M+]: 983.3860; found, 983.8176. Elemental Anal. Calcd for C53H51B2F4N5O8: C, 64.72; H, 5.23; N, 7.12; Found: C, 64.79; H, 5.20; N, 7.16.

2.4. Singlet oxygen detection

1, 3-diphenylisofenylfuran (DPBF) serving as ROS probe was implemented to detect the ROS generation capability of NDB. In detail, 6μL of DPBF (1mg/mL in dichloromethane) was added into 2mL of dichloromethane supplement with NDB photosensitizer (OD510=0.3). Commercial ICG photosensitizer was used as the positive control and dichloromethane only containing DPBF was used as the negative control. Then, the samples were exposed to a 730nm laser (0.1W/cm2), and a UV-visible spectrometer measured the absorbance intensity of DPBF at 410nm. Besides, the dichloromethane solutions with the same concentration of NDB and DPBF were also performed in the darkness to exclude the influence of NDB.

2.5. Preparation of NDB NPs

Under ultrasonic conditions, the tetrahydrofuran solution containing NDB (1mg), DSPE-PEG2000 (8mg), and PEGylated phenylboronic acid (1mg) were quickly injected into 10mL of Mini-Q water.37,38 After sonication, the solution was stirred at room temperature for 12h to remove the tetrahydrofuran. Then the solution was filtered through a 0.22-micron filter needle. The concentration of NDB nanoparticle (NDB NPs) was 0.1mg/mL.

2.6. Photothermal performance analysis

1mL of different concentrations of NDB NPs was placed in a cuvette and treated with 730nm laser light (1.0W/cm2) for 12min (720J/cm2). Meanwhile, an infrared imaging device was applied to record the temperature change in real-time. To analyze the effect of laser power density on photothermal conversion performance, 100μg/mL of NDB NPs was exposed to different power densities of the laser. To assess the photothermal stability of NDB NPs, NDB NPs solution (100μg/mL) was exposed to a 730nm laser for 12min, and then the sample was cooled naturally to room temperature for five times.

2.7. In vitro antimicrobial assay

Staphylococcus aureus was incubated with NDB NPs at 37∘C thermotank for 4h. After treatment with a 730nm laser (1W/cm2) for 10min (600J/cm2), the samples were diluted, and 100μL of diluent were taken to determine the population of viable bacteria through the plate counting method.39,40,41 Then the colony number was monitored using Imaging J software. To further confirm the bactericidal ability of NDB NPs, the bacteria receiving different treatments were stained with live/dead backlight bacterial viability kit before confocal imaging. To investigate the intracellular ROS, the treated bacteria were stained with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate for 3h, condensed, and washed with PBS solution through centrifugation. Finally, the bacteria were observed by a confocal FL microscope.

2.8. Cytotoxicity analysis

The routine cytotoxicity evaluation method was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of NDB NPs towards human immortalized normal HaCaT cell lines.42,43,44 HaCaT cells were precultured in 96-well plates using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle complete medium. After cultivation for 12h, different concentrations of NDB NPs were added and culture for 24h. Then each well was added 15μL of MTT solution (5mg/mL) and the plate was placed in a 37∘C thermotank. After incubation for 3h, the supernatant was removed, and 150μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was perfused to dissolve the formazan. Finally, the cell viability of each well was analyzed by using a microplate reader.

3. Results and Discussion

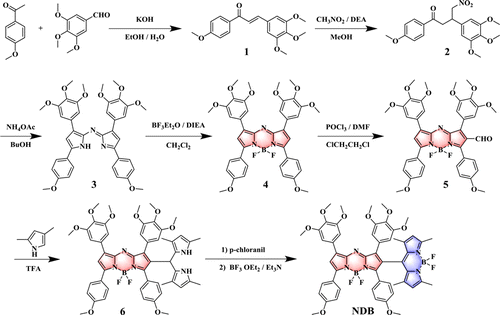

Scheme 2 showed synthesized routes of the Aza-BODIPY-BODIPY dyad NDB. The chalcone 1 was obtained through an aldol condensation reaction, which was further reacted with nitromethane under a mild basic condition to give 2 via Michael addition. Through the reaction between 2 and ammonium acetate in n-Butanol, azadipyrromethene 3 was yielded and transformed to Aza-BODIPY 4 via reacting with Boron trifluoride diethyl etherate. To construct the orthogonal system, β-formyl Aza-BODIPY 5 was first prepared via a standard Vilsmeier–Haack reaction condition of POCl3/DMF. Then, through condensation between 5 and 2, 4-dimethylpyrrole, intermediate 6 was obtained, which was further oxidized with p-chloranil and complexation with BF3 Et2O to construct the Aza-BODIPY-BODIPY dyad NDB. It is to note that excessive 2, 4-dimethylpyrrole was used as the solvent and reagent for the preparation of 6. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was employed to confirm the molecular structure and purity of the dyad NDB (Figs. S1–S12).

Scheme 2. Synthetic route of orthogonal dyad NDB.

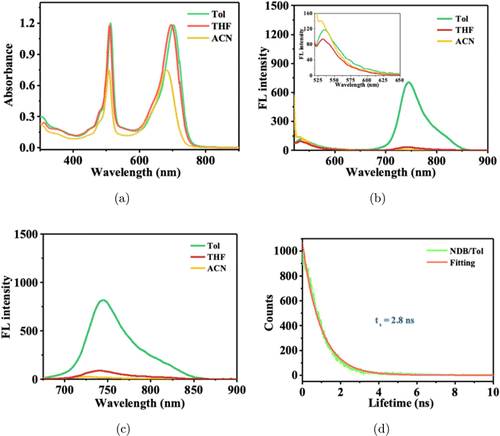

The UV-vis and FL spectra of NDB were recorded in toluene, tetrahydrofuran, and acetonitrile (Fig. 1). The solvents showed negligible effects on the absorption spectra but significantly influenced the FL spectra. The maximum absorption peaks of NDB in toluene were observed at 513 and 703nm, respectively (Fig. 1(a)); thus, the optical band gap was calculated to be 1.65eV. The absorption band peaked at 513nm originated from the BODIPY moiety, and the 703nm absorption band come from the Aza-BODIPY unit, and the two distinct absorption bands indicated the significant steric hindrance between the BODIPY and Aza-BODIPY moieties.45,46 In addition, the FL emission of NDB was also investigated in these organic solvents, and the strongest FL intensity was found in toluene with the peak at 744nm (Figs. 1(b) and 1(c)). The FL lifetime in toluene was also assessed to be 2.8ns through the time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) technique (Fig. 1(d)).

Fig. 1. (a) Absorption spectra of NDB in toluene (Tol), tetrahydrofuran (THF), and acetonitrile (ACN). (b), (c) FL spectra of NDB under the excitation at 512nm and 660nm in Tol, THF, and ACN. (d) The FL lifetime of NDB under excitation at 512nm.

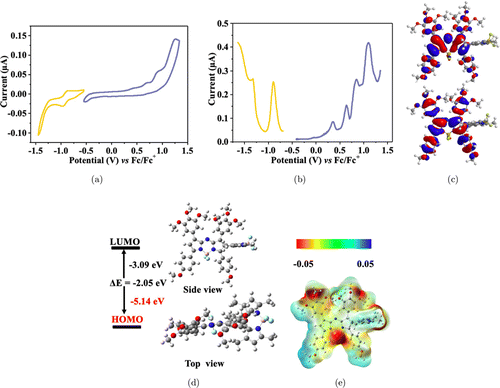

The electrochemical properties of NDB were investigated through cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) in anhydrous dichloromethane. As exhibited in Fig. 2(a), there were two quasi-reversible reduction waves, with the onset reduction potential Eredonset at −0.86V, and the half-wave potential Ered1∕2 at −0.96V and −1.33V. In addition, four quasi-reversible oxidation waves could be observed, with the onset oxidation potential Eoxonset at 0.28V, and the half-wave potential Eox1∕2 at 0.35V, 0.64V, 0.85V, and 1.09V (Fig. 2(b)). Thus, the HOMO and LUMO energy levels are calculated to be −5.08eV and −3.96eV, respectively. The energy gap is determined to be 1.12eV, which is in accordance with the optical energy gap.

Fig. 2. (a), (b) CV and differential pulse voltammetry of NDB in anhydrous dichloromethane. (c) Molecular orbital diagrams of NDB. (d) The optimized molecular structure of NDB. (e) ESP distribution diagram of NDB.

To further explore the molecular geometric and electron cloud of NDB, the electron density allocation and molecular architecture of NDB were simulated by time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculation at the B3LYP/G-31 G(d,p) levels. The molecular frontier orbitals for NDB are exhibited in Fig. 2(c), and the HOMOs and LUMOs were mainly located in the Aza-BODIPY unit. The simulated HOMO/LUMO energy levels were −5.14∕−3.09eV; thus, the theoretical bandgap of NDB was 2.05eV. The optimized geometry of NBD indicated that there was a large torsion angle of 76∘ between the Aza-BODIPY and BODIPY units in NDB molecule (Fig. 2(d)), which was larger than the previously reported 62∘, as indicated the large steric hindrance of NDB.47 The electrostatic potential (ESP) map in the gas phase was also investigated. The negative charges (red color) of NDB molecule were mainly concentrated on the fluorine atoms and oxygen atoms of Aza-BODIPY and BODIPY units. In contrast, the positive charges (blue color) were evenly distributed in the remaining positions (Fig. 2(e)). The results demonstrated a significant structural distortion of NDB, which is beneficial for singlet oxygen generation.

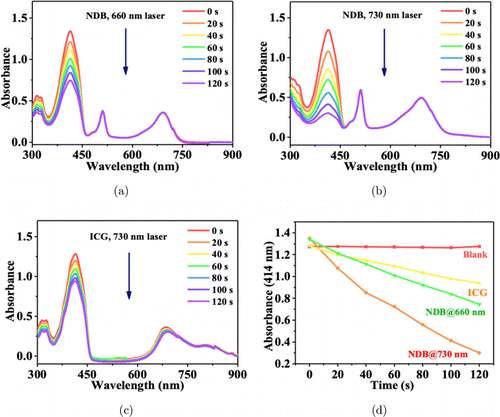

The ROS generation capability of NDB was evaluated by using DPBF (1, 3-Diphenylisobenzofuran) as the probe. After NDB and DPBF were dissolved in dichloromethane and exposed to a 660nm laser (0.1W/cm2), the DPBF absorption at 414nm decreased rapidly with the extension of time. On the contrary, in the control groups of DPBF+laser and NDB+DPBF, the absorbance spectra of DPBF had no significant change (Fig. S13). This result confirmed the good ROS generation capability of NDB under laser irradiation. On account of the maximum absorption peak of NDB at 691nm, both 660nm laser and 730nm laser were used as the excitation light source to investigate the effect of the laser wavelength on the ROS generation performance. As shown in Fig. 3, under 730nm laser irradiation (0.1W/cm2), the absorbance intensity of DPBF dropped from 1.348 to 0.301 for the NDB group in 2min. Under the same conditions, the absorbance of DPBF in the ICG group decreased from 1.282 to 0.941. This result indicated that the ROS generation capability of NDB was 3-folds higher than that of ICG, which was lower than that of iodo-borondipyrromethene (IBPF NPs, 3.4-fold)48 and phenothiazine modified aza-BODIPY (BDP-4DPA NPs, 3.6-fold).11 Besides, a higher ROS generation effect was induced by a 730nm laser than that by a 660nm laser. Therefore, a 730nm laser was applied in the following studies.

Fig. 3. (a), (b) Absorption spectra change of DPBF and NDB under 660nm and 730nm laser irradiation, respectively. (c) Absorption spectra change of ICG under 730nm laser irradiation. (d) The corresponding intensity change curves of DPBF of (a)–(c).

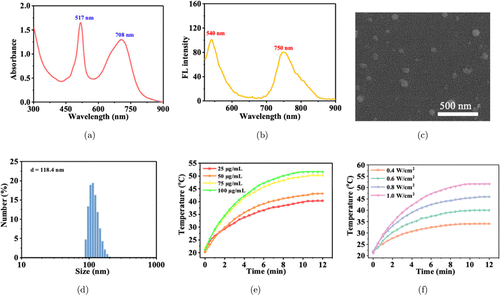

To endow NDB with good hydrophily, low biotoxicity, and strong affinity towards S. aureus, DSPE-PEG2000, and PEGylated phenylboronic acid were used as surfactants to prepare NDB NPs by nanoprecipitation method.12,49 Then, the optical property of NDB NPs was investigated. There were two characteristic absorption peaks at 517nm and 708nm, and two apparent FL emission peaks at 540 and 750nm (Figs. 4(a) and 4(b)). In contrast with NDB in the organic solvent, the redshift of the FL spectrum of NDB NPs may be caused by the intermolecular π–π interaction.36 Then, the size distribution and morphology of NDB NPs were investigated. As depicted in Figs. 4(c) and 4(d), NDB NPs presented a spherical morphology with a hydrodynamic diameter of 118.4nm.

Fig. 4. The absorption (a) and FL (b) spectra of NDB NPs. The SEM image (c) and diameter distribution (d) of NDB NPs. (e) The temperature change curves of different concentrations of NDB NPs under 730nm laser irradiation (1.0W/cm2). (f) The temperature change curves of NDB NPs (100μg/mL) under laser irradiation with different 730nm laser powder densities.

As shown in Figs. 4(e) and 4(f), the temperature of NDB NPs aqueous solution increases along with the extension of the irradiation time, as well as the increased concentration of NPs. The heating rate of NDB NPs solution exhibited a concentration-dependent and laser power density-dependent manner (Figs. 4(e) and 4(f)). Under the 730nm laser irradiation (1.0W/cm2), the temperature of NDB NPs solution (100μg/mL) rose rapidly from 21.1∘C to 51.7∘C; However, under the same conditions, the water temperature fluctuation was not significant (Fig. S14(a)), indicating the excellent photo-to-heat conversion performance of NDB NPs. To further quantitatively study the photothermal effect of NDB NPs, the heating and cooling processes of NDB NPs solution (1mL) were monitored. With the method of fitting, the thermal equilibrium constant is 424.8s (Fig. S14(b)). Thus, the photothermal conversion efficiency of NDB NPs was calculated to be 39.1%,50 which had similar properties to other Aza-BODIPY derivatives, such as 2-pyridone functionalized aza-BODIPY (BDY NPs, 35.7%),19 fluorinated aza-BODIPY (NBF NPs, 39.8%),51 phenothiazine modified aza-BODIPY (BDP-4DPA NPs, 43%),11 and methoxybenzene-modified aza-BODIPY (BDY NPs, 46.6%).36 After five times of alternate “on-off” laser irradiation, NDB NPs solution’s eventual temperature had no noticeable change, indicating the excellent photothermal stability of NDB NPs (Fig. S14(c)).

The above experiment proves that NDB can generate abundant ROS upon exposure to a 730nm laser. We further investigated the ROS generation of NDB NPs within the bacteria. DCFH-DA was adopted as ROS fluorescent probe in this experiment.10 Figure S15 shows that the bacteria incubated with NDB NPs and DCFH-DA under 730nm laser illumination emitted a strong green FL, suggesting abundant ROS generation in the bacteria. In contrast, for the other control groups, no significant FL was observed, indicating no ROS production at all. As demonstrated the effective ROS generation ability of NDB NPs within the bacteria.

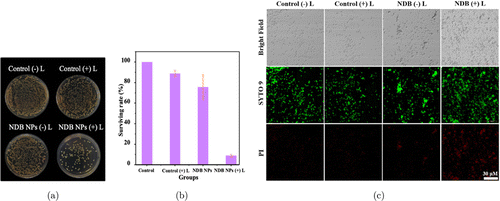

After confirming the photodynamic and photothermal effect of NDB NPs, the antibacterial activity of NDB NPs towards methicillin-resistant S. aureus was investigated by using the plate colony counting method and live/dead bacteria staining.52 First, S. aureus was incubated with NDB NPs (100μg/mL) before exposing the bacteria to a 730nm laser (1.0W/cm2) for 10min. Then the treated sample was spread on LB plate and culture at 35∘C overnight. As displayed in Figs. 5(a) and 5(b), in the NDB NPs+laser group, the number of surviving bacteria decreased significantly. No apparent antibacterial activity was seen in the groups treated with laser and NDB NPs, respectively. The bacterial survival rate was 8% for the NDB NPs+laser group, 75% for the NDB NPs group, and 88% for the laser group (Fig. 5(b)). Further, the sample was incubated in an ice bath to investigate the effect of photothermal performance on bacterial inactivation. As shown in Fig. S16, the antibacterial activity of NDB NPs was weakened upon treatment with an ice bath. This result indicated that NDB NPs hold a prominent antibacterial effect through photodynamic and photothermal therapy.

Fig. 5. (a), (b) The LB plate images and survival rate of bacteria after treating with different conditions. (c) Live and dead bacteria staining after the bacteria treated with different conditions.

Besides, the SYTO 9/PI dual staining was implemented to verify the bactericidal ability of NDB NPs. Both dead and living bacteria can be stained by SYTO 9, while only dead cells are labeled by PI.10,53,54,55 As shown in Fig. 5(c), the bacteria cells treated with NDB NPs+NIR emit a strong red FL, proving that the bacterial integrity was disrupted and resulting in bacteria death. This phenomenon was consistent with the results obtained by the plate counting method.

To evaluate the biocompatibility of NDB NPs, HaCaT cells acting as normal cell model was used for cytotoxicity assay by using the route MTT measure method.56 As shown in Fig. S17, in the absence of light irradiation, the cell survival rate exhibited a slight reduction as the concentration of NDB NPs increased. The cell survival rate is still 74%, even the concentration of NDB NPs up to 400μg/mL. This result demonstrated that NDB NPs showed low toxicity and excellent biological safety under dark light conditions, which could be used for clinical anti-infective therapy in the future.

4. Conclusion

In summary, an orthogonal AzaBODIPY–BODIPY dyad NDB without heavy atoms has been developed as a phototherapeutic agent for photo-initiated antibacterial therapy. The ROS generation of NDB was enhanced due to the twisted molecular structure design that could promote the intersystem crossing. Under the 730nm laser irradiation, the ROS generation capacity is three folds that of ICG. After self-assembly between NDB and PEGylated phenylboronic acid and DSPE-PEG2000, as-obtained NDB NPs possessed good water solubility and favorable biocompatibility. More importantly, with the aid of a 730nm laser, NDB NPs owned satisfactory ROS generation property and high photothermal conversion efficiency of 39.1%. In vitro antibacterial assay indicated that NDB NPs could effectively eradicate methicillin-resistant S. aureus, confirming that NDB NPs were a potential alternative phototherapeutic agent for photo-initiated antibacterial therapy.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (52103166), the National Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20200092, BK20200710), Jiangsu Postdoctoral Science Foundation (51204087), and the Open Project Program of Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics NO.2020WNLOKF022. We are also grateful to the High Performance Computing Center in Nanjing Tech University for supporting the computational resources. Dongliang Yang and Liguo Sun contributed equally to this work.