3-photon fluorescence and third-harmonic generation imaging of myelin sheaths in mouse digital skin in vivo: A comparative study

Abstract

Myelin sheaths wrapping axons are key structures that help maintain the propagation speed of action potentials in both central and peripheral nervous systems (CNS and PNS). However, noninvasive, deep imaging technologies visualizing myelin sheaths in the digital skin in vivo are lacking in animal models. 3-photon fluorescence (3PF) imaging excited at the 1700-nm window enables deep imaging of myelin sheaths, but necessitates labeling by exogenous fluorescent dyes. Since myelin sheaths are lipid-rich structures which generate strong third-harmonic signals, in this paper, we perform a detailed comparative experimental study of both third-harmonic generation (THG) and 3PF imaging in the mouse digital skin in vivo. Our results show that THG imaging also enables visualization of myelin sheaths deep in the mouse digital skin, which shows colocalization with 3PF signals from labeled myelin sheaths. Besides its superior label-free advantage, THG does not suffer from photobleaching due to its 3PF property.

1. Introduction

The lipid-rich myelin sheaths that wrap axons are present in both central and peripheral nervous systems (CNS and PNS). They insulate axons for fast conduction of action potentials. In PNS, myelin-wrapped A and A afferent axons directly carry information encoding touch, pain and temperature from the finger/toe tip to the dorsal root ganglion, which constitutes the initial segment of somatic sensation in these body parts. In order to visualize myelin sheaths for further study, it is important to develop imaging technologies, especially in animal models in vivo.

Multiphoton microscopy (MPM) is a nonlinear optical imaging technology coming in a variety of modalities.1,2,3,4,5,6 MPM uses near-infrared excitation to reduce tissue scattering for deeper penetration. Besides, it is noninvasive with subcellular resolution. Consequently, it is suitable for imaging various structures and even dynamics in animal models and human beings in vivo.

Different MPM modalities have been applied to image myelin sheaths, which can be broadly classified into two categories: labeled and label-free. In the former, exogenous fluorescent dyes which bind strongly to myelin sheaths are introduced into biological samples. The labeled myelin sheaths can be imaged with either 2-photon fluorescence (2PF) or 3-photon fluorescence (3PF) microscopy.7,8 In terms of label-free MPM, the following modalities have been demonstrated with different contrast mechanisms: (1) third-harmonic generation (THG) microscopy. Myelin sheath is rich in lipid, which generates strong third-harmonic signals upon excitation with femtosecond laser pulses.3,4,9 (2) Coherent Raman scattering (CRS) microscopy. The lipid content in the myelin sheath is rich in CH2 stretching frequency, which can be readily detected and imaged through CRS microscopy.10,11,12

Most biological samples are heterogenous, which exerts scattering onto the excitation light in MPM. Skin as a multilayered structure is highly scattering. An effective means to reduce scattering-induced attenuation of excitation light is to shift its wavelength to the longer window. Both 1300-nm and 1700-nm windows have been demonstrated to be suitable for deep-skin imaging.8,13,14,15 MPM at these excitation windows provides a necessary extension in imaging depth to the well-established 2PF and second-harmonic generation (SHG) imaging excited at the 800-nm window.16,17

Recently, we demonstrated that 3PF excited at the 1700-nm window, in combination with local injection of an exogenous fluorescent dye-Fluoromyelin red, is a promising technology for imaging myelin sheaths in PNS such as mouse digital skin.8 The injection of exogenous dye makes this technology less appealing for its potential application on human subjects, which requires label-free especially for in vivo imaging. According to the aforementioned introduction, myelin sheaths can be imaged through THG microscopy in both brain and spinal cord, which is label free. In this paper, we demonstrate a comparative study of THG imaging and 3PF imaging of myelin sheaths in the mouse digital skin in vivo, excited at the 1700-nm window. Our results clearly show that THG imaging at this window provides a promising label-free technology for visualizing myelin sheaths deep in the digital skin.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental setup

As was mentioned in Ref. 8, the fluorescent dye FluoroMyelin red could generate 3PF upon excitation at the 1700-nm window. Therefore, we used a 1665-nm soliton source as the excitation laser.

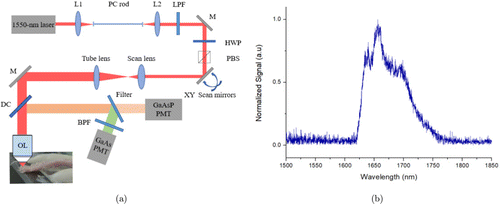

Our experimental setup [Fig. 1(a)] is similar to that used in Ref. 8: the 1665-nm soliton source was generated through soliton self-frequency shift,18 pumped by a 500-fs, 1550-nm femtosecond laser (FLCPA-02CSZU, Calmar) at 1 MHz. A 44-cm photonic-crystal rod (SC-1500/100-Si-ROD, NKT Photonics) was used to shift the soliton to 1665nm. A f = 100mm C-coated achromatic lens (AC254-100-C-ML, Thorlabs) lens and a f = 75 mm C-coated achromatic lens (AC254-075-C-ML, Thorlabs) lens were used to focus the pump laser into the PC rod and to collimate the output solitons, respectively. By tuning the slight angle of a 1635-nm long-pass filter (1635lpf, Omega Optical), the residual pump was removed. The measured soliton spectrum is shown in Fig. 1(b). The filtered solitons were sent into a laser scanning microscope (MOM, Sutter) for MPM. The combination of a half-wave plate (AHWP05M-1600, Thorlabs) and a polarizing beam splitter cube (PBS104, Thorlabs) was used to continuously adjust the soliton power on the sample. The maximum optical power after the objective lens was 35.4mW, and was only used for imaging the deepest structures.

Fig. 1. (a) Experimental setup. L1: f = 100mm lens; L2: f = 75mm lens; LPF: 1635-nm long-pass filter; HWP: half-wave plate; PBS: polarization beam splitter cube; DC: dichroic mirror; OL: objective lens; BPF: bandpass filter. (b) Measured soliton spectrum.

Unlike the system in Ref. 8, in this experiment, simultaneous acquisition of both 3PF and THG imaging could be performed with the following settings: a GaAs photomultiplier tube (PMT, H7422p-50, Hamamatsu) with a 558/20-nm bandpass filter (FF01-558/20-25, Semrock) was used to detect THG signals; 3PF images were acquired using a GaAsP PMT (H7422p-40, Hamamatsu) with both a 630/92-nm bandpass filter (FF01-630/92-25, Semrock) and a 593-nm long-pass filter (FF01-593/LP-25, Semrock). A water immersion objective lens (XLPLN25XWMP2, NA = 1.05, Olympus) with 2-mm working distance (WD) was used. The objective lens was overfilled. D2O immersion was used. Image acquisition and processing were performed using ScanImage (Vidrio Technologies, Ashburn, Virginia) and ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland), respectively. For tissue imaging, the acquisition speed was 2 ms/line with 2 averages, with a resultant frame rate of 0.5 frame/s for a pixel size of 512 × 512. Imaging stitching was performed for some images to visualize myelin sheaths at large scales.

2.2. Animal procedures

Animal procedures were reviewed and approved by Shenzhen University. The mice (Balb/c) were all from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center, aging between 6 and 8 weeks. Mice were anesthetized using a gaseous anesthesia system (Matrx VIP 3000, Midmark). Body temperature was kept at C with a heating pad. Dental cement was used to fix the middle digit in the hind foot between cover slip and glass slide. The cover slip was in close contact with the digit. 10-L FluoroMyelin red solution (1:5 diluted in PBS) was injected into the fingertip through a 34G ultra-thin wall nanoneedle (JBP3404, Japan Bio Products). Water was added between the cover slip and the glass slide to immerse to digit. Imaging was performed min after injection closure, which was long enough to label the myelin sheaths.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. 3PF and THG imaging of myelin sheaths in vivo: Colocalization analysis

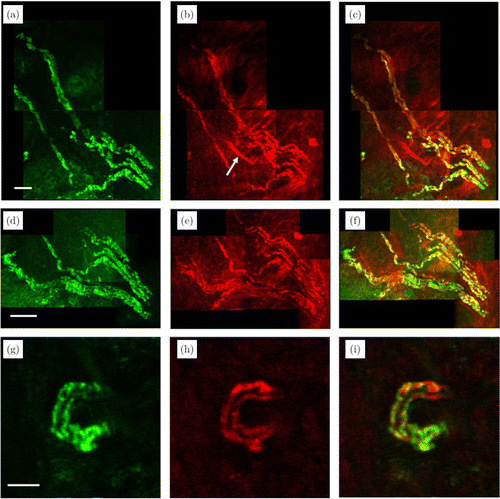

First, we performed simultaneous 3PF and THG imaging of myelin sheaths in the mouse digital skin in vivo to analyze their colocalization. As shown previously,8 Fluoromyelin Red binds to and labels myelin sheaths. Upon excitation by the 1665-nm femtosecond pulses, 3PF images clearly reveal the tubular structure of myelin sheaths [Figs. 2(a), 2(d), 2(g)]. Simultaneously, acquired THG images also show tubular structures [Figs. 2(b), 2(e), 2(h)]. After we merge both 3PF and THG images, we can see the colocalization of the tubular structures [shown in yellow in Figs. 2(c), 2(f), 2(i) by merging red and green]. As a result, THG microscopy can be used for label-free imaging of myelin sheaths in the PNS of mouse digital skin in vivo. This is expected given that THG microscopy has been applied to imaging of myelin sheaths in both brain and spinal cord.

Fig. 2. Simultaneously acquired 3PF (a), (d), (g) and THG (b), (e), (h) images of the mouse digital skin in vivo, at different spatial scales. The merged images are shown in (c), (f), (i). (a)–(c) and (d)–(f) are maximum z projections of 2D images from 160 to 190m below the skin surface, each 2D image spaced by 2m axially. (g)–(i) are 2D images 204m below the skin surface. Scale bars: (a)–(c): 50m; (d)–(f) :100m; (g)–(i):10m.

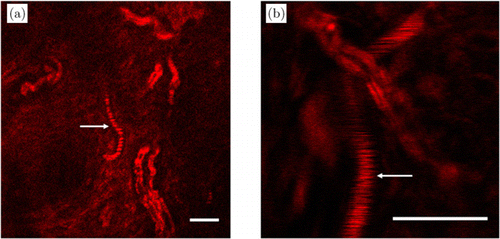

In the THG image in Fig. 2(b), indicated by arrow, we can also see tube-like structures similar to myelin sheaths but not labeled by Fluoromyelin red. These structures are blood vessels. They can be clearly resolved and differentiated from myelin sheaths upon zooming in, with representative images shown in Fig. 3. The main differences of these two structures in THG images are: (1) myelin sheaths have a tubular structure as they wrap axons and axons do not generate detectable THG signals. (2) Blood vessels look like “solid tubes” and show stripes. This is due to the origin of THG signals within blood vessels: red blood cells generate THG upon excitation19,20,21,22 which gives rise to the appearance of “solid tubes”. Since red blood cells are constantly moving within blood vessels, this yields the stripe appearance [arrow in Fig. 3(b)]: when the laser scanning line overlaps with a moving red blood cell, it generates THG signals and thus a bright line; when the laser scanning line is between two adjacent red blood cells, no THG is generated and a dark line is formed. When the blood flow speed is slow, individual red blood cells can be resolved [arrow in Fig. 3(a)].

Fig. 3. THG images 152m (a) and 215m (b) below the skin surface show both myelin sheaths and blood vessels. Blood vessels are indicated by arrows. Scale bars: 20m.

3.2. Deep-skin 3PF and THG imaging of myelin sheaths in vivo: Maximum imaging depth of both modalities

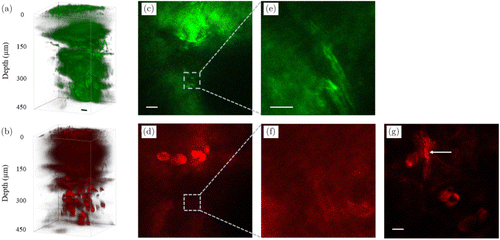

In this subsection, we compare the deepest myelin sheaths that can be imaged with both 3PF and THG imaging. Representative 3D stacks are shown in Fig. 4. For both 3PF and THG imaging, structures can be resolved at 420m below the skin surface [Figs. 4(a)–4(e)]. For all the 17 mice we have imaged, the deepest myelin sheaths that can be resolved are 400m below the skin surface [Figs. 4(c) and 4(e)]. However, in the simultaneously acquired THG image at the same depth, the same myelin sheaths cannot be resolved [Figs. 4(d) and 4(f)]. This indicates that 3PF imaging enables deeper imaging of myelin sheaths in the mouse digital skin.

Fig. 4. 3D stacks of simultaneously acquired 3PF (a) and THG (b) imaging. (c), (d) and (e), (f) are maximum z projections of 2D images from 390 to 420m and 390 to 400m below the skin surface, respectively, each 2D image spaced by 2m axially. Scale bars: (a)–(d), (g): 30m; (e), (f) :10m. (g) myelin sheaths are indicated by the arrow which is from a different mouse and 294m below the skin surface. Optical power on the surface was 5.4mW, and gradually increased to 35.4mW as imaging depth increased.

For all the 17 mice we have imaged, the deepest myelin sheaths that can be resolved by THG are 300m below the skin surface [indicated by the arrow in Fig. 4(g), from a different mouse in Figs. 4(a)–4(f)]. Our observation that 3PF is better in imaging deeper structures than THG in scattering biological samples is consistent with previous experimental results in other biological samples. In through-the-skull mouse brain imaging, 3PF images of blood vessels and other brain structures deeper than THG23 are also verified by our group (not published). In mouse brain after craniotomy, 3PF images of blood vessels (2100m below the brain surface24) much deeper than THG (900m below the brain surface22) were taken. Both 3PF and THG signals are dependent on the cubic of excitation power. As the imaging depth increases, the excitation power decays the same way for both 3PF and THG imaging, besides, aberration increases and distorts the excitation beam the same way. Since THG signals are sensitive to structures,9,25,26 we postulate that the combined effect of aberration and structure sensitivity leads to the deterioration of THG in resolving deeper structures. This postulation, however, needs further investigation and is beyond the scope of this paper.

3.3. Photobleaching in 3PF imaging

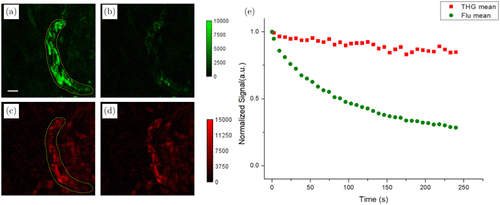

It is well known that fluorescence imaging suffers from photobleaching upon repetitive exposure to excitation light, which is a major drawback compared with label-free imaging. In this subsection, we investigate whether such photobleaching exists in 3PF imaging of Fluoromyelin red labeled myelin sheaths. We performed simultaneous time-lapse 3PF and THG imaging of myelin sheaths 220m below the skin surface over a time span of 240s. The excitation power of the objective lens was 6mW. Representative images acquired at t = 0s and t = 240s are shown in Fig. 5. We can see that upon repetitive exposure to the excitation light, 3PF images suffer from noticeable decrease in signal level, while THG signals do not.

Fig. 5. Time-lapse 3PF (a), (b) and THG (c), (d) images acquired at t = 0 (a), (c) and t = 240s (b), (d). (e) Normalized 3PF (green circles) and THG (red squares) signals versus time. The 3PF and THG signals are calculated as the mean values encircled in (b) and (d), respectively. Scale bars: 10m.

In order to give a quantitative estimation of the time-dependent 3PF and THG signal levels, we encircled the same area of myelin sheaths in Figs. 5(a) and 5(c), calculated the mean 3PF and THG signals within this area as a function of time, and normalized signals to t = 0 to illustrate the decay. The normalized 3PF and THG signals versus time are plotted in Fig. 5(e). Photobleaching of Fluoromyelin red is manifested by the conspicuous decay of 3PF signal over time.

It also seems surprising that THG signals also decay slightly over time upon repetitive exposure to excitation light. We measured excitation power after the objective lens and found virtually no change. This slight THG signal decay is due to the immersion D2O used in the experiment: in our previous demonstration, D2O absorbs water vapor from the environment which leads to a time-dependent decrease in excitation power on the sample and hence the THG signals.27 If we replace the D2O with fresh one, THG signals will restore, but 3PF signals will not. So, these comparative imaging experiments show that 3PF signals may suffer from time-dependent degradation upon repetitive scanning, while THG signals may not.

4. Conclusion

THG as a powerful label-free imaging technique has been found for successful applications even on human subjects.13 Here, we show that THG imaging is also promising for visualizing myelin sheaths in PNS in mouse digital skin in vivo. Compared with fluorescence imaging, the key advantage of label free and thus photobleaching free makes THG imaging excited at the 1700-nm window appealing for human subjects. 3PF imaging, in contrast, provides better resolution at the deepest region of the skin, but suffers from photobleaching upon repetitive exposure to excitation light. These two imaging modalities may cater to different needs for studies on myelin sheaths in the digital skin, with the common merit of deep-skin penetration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (61775143, 61975126); the Science and Technology Innovation Commission of Shenzhen under (No. JCYJ20190808174819083, JCYJ20190808175201640, KQTD20150710165601017).