Development of a poly(arylene sulfide sulfone) antibacterial electrospun film as a skin wound dressing application

Abstract

Tissue engineering has become a hot issue for skin wound healing because it can be used as an alternative treatment to traditional grafts. Nanofibrous films have been widely used due to their excellent properties. In this work, an organic/inorganic composite poly(arylene sulfide sulfone)/ZnO/graphene oxide (PASS/ZnO/GO) nanofibrous film was fabricated with the ZnO nanoparticles blending in an electrospun solution and post-treated with the GO deposition. The optimal PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film was prepared by 2% ZnO nanoparticles, 3.0g/mL PASS electrospun solution, and 1% GO dispersion solution. The morphology, hydrophilicity, mechanical property, and cytotoxicity of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film were characterized by using scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscope, water contact angle, tensile testing, and a Live/Dead cell staining kit. It is founded that the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film has outstanding mechanical properties and no cytotoxicity. Furthermore, the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film exhibits excellent antibacterial activity to both Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Above all, this high mechanical property in the non-toxic and antibacterial nanofibrous film will have excellent application prospects in skin wound dressing.

1. Introduction

Skin is the outer protective layer covering the entire body and the largest human organ that accounts for approximately 15% of the total body mass. A skin wound is generally produced by burn, chronic ulceration, or accidental trauma. The damaged skin is difficult to initiate the healing process during bacterial infection, bringing life threatening infections.1,2 A skin dressing is used to promote healing as an assist material. An ideal skin wound dressing should have an antibacterial ability to prevent infection, allowing moisture permeation to promote epithelization and support cell proliferation.3,4,5,6 For this purpose, different carriers are represented, such as foams,7 hydrogels,8 and films.9,10 Films are a major form for skin wound dressing, especially electrospun nanofibrous films. Electrospinning is an effective way for the fabrication of small-size nanofibers.11,12,13 The obtained electrospun nanofibrous films have excellent properties, such as high oxygen permeability, high surface to volume ratio, and structural similarity to the extracellular matrix, making them have a wide application in skin wound dressing.14,15

Various antibacterial agents were added into the electrospun nanofibrous films to achieve efficient antibacterial properties.16,17 Shen prepared a tigecycline-loaded sericin/poly(vinyl alcohol) composite film via electrospinning and carried out the application as antibacterial wound dressings.13 The antibacterial property was proven by the obvious bacteriostatic circle. However, the antibacterial property decreased with increase in time due to the decrease of drugs released. Meanwhile, the human body could also build up a tolerance to it with the usage of the drug. Inorganic antibacterial agents possess high stability and safety, which spoils the bacteria by eliminating proteins or contacting microbial cell films, such as Ag, TiO2, ZnO, and Cu metal nanoparticles.19,20,21,22 The ZnO nanoparticles have been intensively studied for bacterial inhibition.23 The incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles into the polymer matrix during the electrospinning process will endow the antibacterial property of the electrospun nanofibrous film. However, the poor dispersion and low adhesion of ZnO nanoparticles would bring the decrease of mechanical properties and limit their applications. The introduction of the other suitable materials forming the inorganic/organic electrospun nanofibrous film will be a feasible method to solve the decrease of mechanical property of the skin wound dressing. Two-dimensional materials have been widely used in the biomedical field.24,25,26 Graphene oxide (GO), as the two-dimensional layered structure organic antimicrobial material, exhibits good biocompatibility and antibacterial property.27,28 Meanwhile, GO contains amounts of functional groups, such as hydroxyl and carbonyl, on its nanosheet basal plane and edge.29,30 These functional groups could happen to interact with polymer matrices. Thus, GO is considered a suitable one for improving both the mechanical and antibacterial properties of wound dressing.

In this study, poly(arylene sulfide sulfone) (PASS) was chosen as the polymer resin with high thermal stability and biocompatibility.31,32,33 And then, PASS resin and ZnO nanoparticles were blended for forming a homogeneous spinning solution, and then the fabricated PASS/ZnO nanofibrous film. Finally, GO was evenly deposited on this composite nanofiber-based film to fabricate the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film as a wound dressing. The morphology, hydrophilicity, and cytotoxicity were evaluated. The mechanical and antibacterial properties were also studied systematically. The PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film not only exhibited good mechanical property but also represented excellent antibacterial property with the synergistic effect of ZnO nanoparticles and GO.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Poly(arylene sulfide sulfone) (PASS) was obtained in our laboratory. N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (China). ZnO nanoparticles were bought from Zhuotai New Material Technology Co., Ltd. (China). Graphene oxide (GO) was produced by XFNANO Co., Ltd. (China).

2.2. Fabrication of PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film

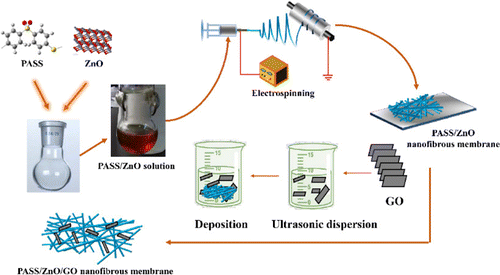

2.4g, 2.7g, and 3.0g PASS were dissolved in 10mL NMP to form a PASS electrospun solution. Then, 1wt.% and 2wt.% ZnO nanoparticles were added individually into the PASS homogeneous solution, forming a PASS/ZnO electrospun solution. All the electrospun nanofibrous films were prepared as the following steps: the as-prepared electrospun solutions were stored in a 3mL plastic syringe and a high-voltage generator (ZGF ChuanGao Electro-tech Inc., China) provided a high voltage of 14kV. PASS and PASS/ZnO electrospun nanofibers were dried after further volatilizing the solvent. After that, PASS/ZnO electrospun nanofibers were put 1% GO dispersion with ultrasonic treatment for 20mins for preparing the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film. Figure 1 represents a schematic illustration of the preparation procedure.

Fig. 1. Schematics of the preparation of PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films.

3. Characterization

These nanofibers were tested by scanning electron microscopy (SEM & EDS Inspector F) and a soft-image J was used for measuring the diameter with 200nanofibers of the samples. The mechanical property was characterized via a tensile tester (MTS E45). Each nanofibrous film was prepared 60 × 10mm spline stretched at 10mm/min. The moisture permeability of the nanofibrous film was obtained by testing the water vapor permeance (WVT) with the ASTM E96 water method via a YG 601H machine. The hydrophilicity of the samples was evaluated by the water contact angle via a video optical contact angle system (DSA100, Kruss, Hamburg). Cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) after incubation using HCT116 cell for 1day, 3days, and 5 days. Thereafter, the fluorescence at 563nm excitation at 587nm emission was tracked using a Tecan Infinite M200plate reader. In addition, the cell morphology was measured using scanning electron microscopy. The antibacterial activity was measured by the colony counting method using Escherichia coli (E. coli, ATCC 8739) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, CMCC 26003). The antibacterial rate (N) was measured by counting the colonies and calculating according to the below equation,

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Morphologies of PASS, PASS/ZnO, PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film

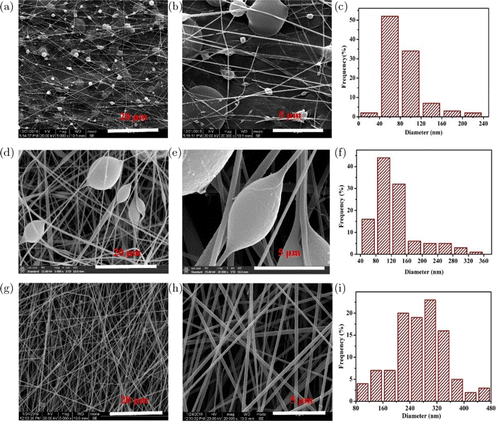

The morphology of the fiber directly affects the performance of the nanofibrous film. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the optimal morphology of the fiber. Figure 2 represents the morphology of the PASS nanofiber with different concentrations of electrospun solutions. As shown in Figs. 2(a)–2(c), a large quality of beads and small diameter (73nm) nanofibers existed in this nanofibrous film when the concentration of the electrospun solution was 0.24g/mL. With the concentration of the solution increased to 0.27g/mL, the bead structure reduced and the diameter of the nanofiber was up to 161nm (Figs. 2(d)–2(f)). When the concentration was 0.30g/mL, no beads existed in the whole nanofibrous films, and the nanofiber was smooth and uniform, and the average diameter was 259nm (Figs. 2(g)–2(i)). This result confirms that PASS electrospun solution concentration greatly affects the fiber morphology and diameter, and the uniformity and diameter of the nanofiber increase with increase in the concentration electrospun solution. The main reason is that the concentration of the electrospun solution directly alters the solution property, such as the viscosity, surface tension, and conductivity. Above all, the PASS nanofibrous film with the concentration of 0.30g/mL was chosen for further investigation with the smooth and uniform nanofibers.

Fig. 2. Scanning electron microscopy images of fibrous films fabricated from (a)–(b) 0.24g/mL solution, (d)–(e) 0.27g/mL solution, and (g)–(h) 0.30g/mL solution. Nanofiber diameter distributions of PASS nanofiber fabricated from (c) 0.24g/mL solutions, (f) 0.27g/mL solutions, and (i) 0.30g/mL solution.

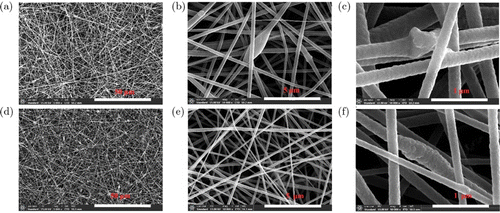

The effect of ZnO nanoparticles’ doping on the PASS/ZnO nanofiber morphology was investigated by SEM images. Figure 3 displays the SEM images of the PASS/ZnO 1% and PASS/ZnO 2% nanofibrous film. Comparing with the PASS nanofibrous film, the PASS/ZnO nanofibrous film became inhomogeneity and the “beaded” structure appeared. The ZnO nanoparticles agglomerated in the PASS/ZnO nanofibers, as seen in Figs. 3(c) and 3(f). A possible explanation is that ZnO nanoparticles may happen to gather, which will result in the change of viscosity and conductivity of an electrospun solution. The concentration of ZnO nanoparticles is limited to 2% because the higher concentration of ZnO nanoparticles will increase the solution viscosity and cause poor electrospinnability.

Fig. 3. Scanning electron microscopy images of fibrous films fabricated from (a)–(c) PASS/ZnO 1wt.% solution and (d)–(f) PASS/ZnO 2wt.% solution.

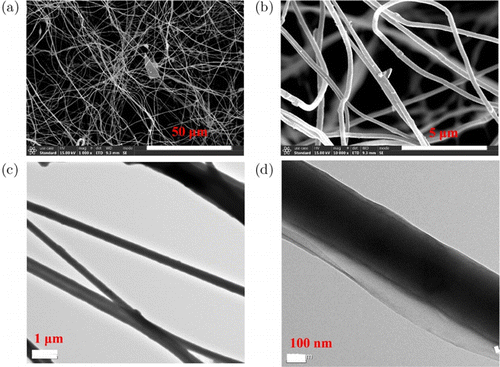

A PASS/ZnO 2wt.% nanofibrous film was chosen to study furtherly for fabricating of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film due to the more ZnO antibacterial nanoparticles. The morphology structure of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibers is represented in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 4(a), a small amount of blockbuster of GO was observed on the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film. Furthermore, there were also some changes for the single PASS/ZnO/GO nanofiber (Fig. 4(b)). After further observation, a transmission electron microscope of PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films is shown in Figs. 4(c) and 4(d). GO was wrapped on the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofiber, which demonstrates that the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film was successfully prepared.

Fig. 4. (a), (b) Scanning electron microscopy images and (c), (d) transmission electron microscope of PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films.

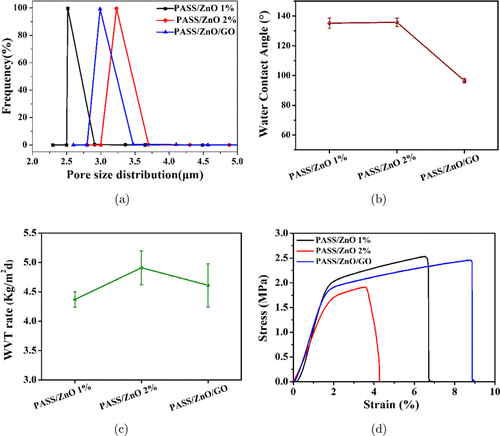

The properties of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films were systematically investigated. The result is shown in Fig. 5. As shown in Fig. 5(a), all nanofibrous films represented a narrow pore size distribution ranging from 2.5to 3.8μμm, which revealed that the PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films endowed a uniform pore distribution. The average pore sizes of PASS/ZnO 1% and PASS/ZnO 2% were 2.58and 3.21μμm, respectively. This result verifies that the aggregates of ZnO nanoparticles would increase the distances of nanofibers, resulting from the enlarged inter-fiber voids. With the addition of GO, the average pore size was 2.97μμm, which is smaller than the PASS/ZnO 2% nanofibrous film. The decreased pore size is caused by the flake GO scattered on the nanofibrous film, which blocked a part of the pore size. The water wettability of the PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film was first examined. As shown in Fig. 5(b), the water contact angles were 135.3∘, 136.1∘, and 98.7∘ for the PASS/ZnO 1%, PASS/ZnO 2%, and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film, respectively. All these nanofibrous films showed hydrophobicity due to the micro-nano structure. However, the contact angle of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film is lower than that of the PASS/ZnO one. The result demonstrated that the hydrophobicity decreased with the addition of the highhy drophilicity GO.34 The low hydrophobicity of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film is helpful to adhere to the wound dressing. Furthermore, the moisture permeability of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film is seen in Fig. 5(c); there are some changes among the different nanofibrous films. As the ZnO content increased from 1to 2wt.%, the WVT rate ascended from 4.34to 4.91kg/m2 d, attributing to the increase in the porosity size. However, with the treatment of GO, the WVT of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film descended to 4.56kg/m2 with decrease in pore size. The result demonstrates that the WVT rate of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film is higher compared with the traditional wound dressing. Furthermore, the stress–strain curves of the PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films were obtained and are shown in Fig. 5(d). The PASS/ZnO 1% and PASS/ZnO 2% nanofibrous film yielded a tensile stress of 2.47 MPa and 1.98 MPa and the break extension is 6.81% and 4.24%, respectively. With more content of ZnO nanoparticles, the tensile stress and elongation at the break of the PASS/ZnO 2% nanofibrous film decrease, which is in agreement with the previous report. The main reason is that more ZnO nanoparticles gathered and caused defects, which is not a benefit from the mechanical property. With the addition of GO, the tensile stress and break extension of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films increased to 2.34 MPa and 8.91%, respectively, which is higher than those of the PASS/ZnO 2% nanofibrous film. This causes the interfacial interaction between the GO and PASS/ZnO 2% nanofibrous film, enhancing the tensile strength with the high mechanical property of GO and improving elongation at the break of the film significantly with the overlap between the GO and PASS/ZnO 2% nanofibrous film. The as-prepared PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film exhibits higher tensile property and elongation at break, which would have great advantages in practical applications.

Fig. 5. The property of PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films: (a) pore size distribution; (b) water contact angle; (c) water vapor permeance (WVT); and (d) stress–strain curves.

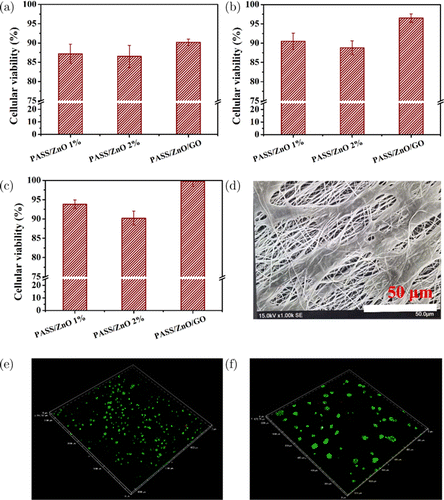

Cell viability is an important one to evaluate the cytotoxicity for the use of skin wound dressing. A Live/Dead cell vitality assay kit was used to assess cell viability. In this work, the HCT116cells were cultured on the PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film for 1 day, 3 days, and 5 days. The results are represented in Fig. 6. The viability of the HCT116cells of the PASS/ZnO 1%, PASS/ZnO 2%, and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film was 87.3%, 86.5%, and 90.2%, respectively, after 1day (shown in Fig. 6(a)). It might be attributed to the hydrophobicity of the nanofibrous film. However, it is observed that the cells significantly proliferated on the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film as compared with the PASS/ZnO one after 3days (Fig. 6(b)). With further increase in time to 5days, the HCT116cells treated with the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film still exhibited excellent proliferative activity close to 100% (Fig. 6(c)). Furthermore, it is obvious that the MC3T3cell attached and grew well on the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film, which is consistent with the results obtained by the Live/Dead cell vitality (Fig. 6(d)). This result was confirmed furtherly by the Live/Dead fluorescence staining with different magnifications (Figs. 6(e) and 6(f)). Large amounts of live cells were stained with green fluorescence, while only small amounts of cells were stained in red fluorescence, indicating that the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films have good cytocompatibility and no cytotoxicity.

Fig. 6. Cytotoxicity test of PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film, the cellular viability treated with PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film for (a) 1day, (b) 3days, (c) 5days. The data represent the mean ±± standard deviation (SD) from three repeated measurements. (d) The morphology of MC3T3cells attached to PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film after 5-day culture. Fluorescent images of Live/Dead staining of MC3T3on PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film culturing for 5days (e) with 3000μμm*3000 μμm and (f) 1200 μμm*1200 μμm. Live cells were stained in green while dead cells were stained in red.

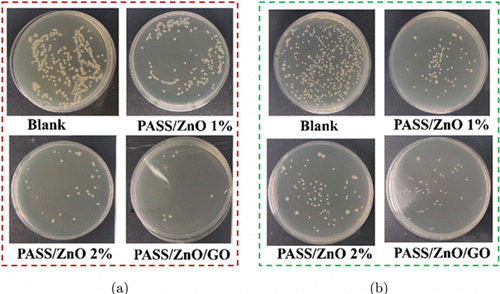

The antibacterial property of the nanofibrous film was investigated by the agar diffusion method. Figure 7 illustrates the colony growth of E. coli and S. aureus treated with PASS/ZnO 1%, PASS/ZnO 2%, and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film for 4h. The bacterial growth was directly obtained via the optical image. The treated PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film showed significant variations in bacterial colonies compared with the control group for the E. coli and S. aureus. The least bacteria were observed with the existence of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film, which indicated that the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film had the best antibacterial property. Furtherly, the antibacterial activity of the nanofibrous film was quantified by measuring the number of colonies.

Fig. 7. The optical images of the blank one and the experimental one with PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous for the (a) E. coli bacterial and (b) S. aureus antibacterial growth.

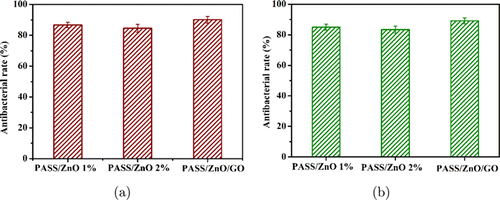

The antibacterial activity of the PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film was tested and is shown in Fig. 8. The PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films exhibited antibacterial activity against E. coli of 89.12%, 88.91%, and 92.2%. The PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films exhibited outstanding antibacterial property. Meanwhile, the excellent antibacterial activity of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous films for S. aureus antibacterial growth is shown in Fig. 8(b). The main reason is the synergy effect of the ZnO nanoparticles and GO.

Fig. 8. The antibacterial property of PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film: (a) the antibacterial rate of PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film for E. coli bacterial growth and (b) the antibacterial rate of PASS/ZnO and PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film for S. aureus antibacterial growth.

5. Conclusion

The potential of the PASS/ZnO/GO electrospun nanofiber film is demonstrated for the first time with outstanding mechanical and antibacterial properties for wound dressing. The PASS/ZnO/GO electrospun nanofibrous film was fabricated with 2% ZnO nanoparticles blending in the 3.0g/mL PASS electrospun solution and post-treated with the 1% GO dispersion solution. It is founded that the tensile stress and break extension of the PASS/ZnO/GO nanofibrous film are 2.34 MPa, 8.91%, respectively. More importantly, the antibacterial rate is 92.2%. The as-prepared PASS/ZnO/GO electrospun nanofibrous film has outstanding mechanical and antibacterial properties. This composite nanofibrous film will have wide applications, especially in wound dressing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Nos. 51573103and 21274094), the 2019foundation research fostering project-21, and the postdoctoral fund (2019SCU12007) from Sichuan University, financially supported by the State Key Laboratory of Polymer Materials Engineering (Grant No. sklpme2020-3-02). We are particularly indebted to Yi He from the Analytical & Testing Center of Sichuan University.