Stochastic complex integrals in a two-dimensional flow

Abstract

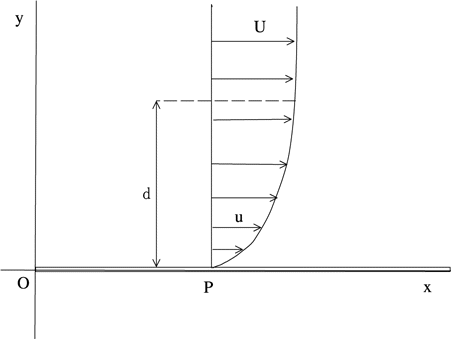

Two-dimensional flow is considered in the xy plane. A flat plate is placed parallel to the x-axis. The circulation of the flow is investigated and it is the real part of the stochastic complex integral. In that study, analogs of Karhunen–Loève expansions for stochastic complex integrals are studied.

1. Introduction

We consider two-dimensional flow of a liquid in the xy plane. Suppose every fluid particle moves with the constant speed U parallel to the x-axis. Place a flat plate on the xy plane with its leading edge coinciding with x=0, as shown in Fig. 1. For example, see the example on p. 80 in Chorin and Marsden’s book1 or Sec. 23.20 in Milne-Thomson’s book.2

Fig. 1. Velocity profile near the plate.

The fluid velocity on the plate surface is the same as that of the plate, that is, it is equal to zero. On the other hand, the fluid velocity in the regions far from the plate is equal to U. The fluid velocity drastically changes in the neighborhood of the plate surface. This region is called a boundary layer. In Fig. 1, d denotes the thickness of the boundary layer. When the flow rate is small, the flow is laminar. Then we denote by u(x,y)=(u(x,y),v(x,y)) the velocity of the fluid particle that is moving through (x,y). Here, the flow is steady. When the flow rate increases, we suppose that a random force acts on the flow in the y-axis direction. Under this assumption, we investigate the circulation in the boundary layer. We adopt the following stochastic process {Zy} as a random force :

Theorem 1.1. Let the length of C be finite. If u is of class C1, the circulation Γ is given by

Remark 1.1. Let ν>0. Suppose the pressure gradient dp∕dx is equal to zero, and consider the boundary layer equation

Stochastic integrals of nonrandom functions with respect to additive processes on ℝ were studied in Refs. 6,7, and 8. See also Refs. 9–11. Sato developed this theory in Refs. 12 and 13. These days, a lot of papers related to this theory exist, for example, Refs. 14–18. Stochastic complex integrals are constructed on basis of this theory in Ref. 19. Our study extends to the application to Blasius’ formula of fluid mechanics in Ref. 20. The paper is written to be as self-contained as possible. The terminologies follow Ref. 21.

2. Covariance Functions

We find the covariance functions, before we define the stochastic integrals with respect to {Wky}.

Lemma 2.1. The law of Wky is represented as

Lemma 2.1 is derived from Proposition 2.6 of Ref. 7. Lemma 2.1 tells us that the mean of Wky is equal to 0, that is

Lemma 2.2. The second moment of Wky is represented as

Proof. From Lemma 2.1, we obtain that

Lemma 2.3. For h>0, it holds that

Proof. Since we have

Lemma 2.4. For h>0, it holds that

Proof. We have

We give the covariance function of Wkt.

Theorem 2.1. The covariance function of Wky is represented as

Proof. Let h=|s−y|. From Lemmas 2.2 and 2.4, we obtain that

3. Karhunen–Loève Expansions

Let −∞<−A≤a<b≤A<∞. We first discuss the existence of the integral

Definition 3.1. If the quadratic mean limit of Q(g,Δn) exists as |Δn|→0 and is independent of the choice of {Δn} and, for each Δn, is independent of the choice of {ỹni}, then the limit is denoted by

Theorem 3.1. If g(y) is continuous on [a,b], then the integral ∫bag(y)Wk(y)dy exists as a quadratic mean limit.

Proof. We have

Assume that Υk≠0. We next consider the integral equation

Lemma 3.1. The integral equation (6) is not satisfied for any μ>2.

Proof. Equation (7) has the general solution

Hence, we see from Lemma 3.1 that if (6) has a nontrivial solution, then 0<μ<2. We consider the equation

Proposition 3.1. Eigenvalues for (5) are

Proof. Now we have

Here, we show the range of each eigenvalue.

Proposition 3.2. If n≥0, then

Proof. If n≥0, then

Now we find the orthonormal eigenfunctions required for the Karhunen–Loève expansion.

Proposition 3.3. Let

Proof. Let fn(u)=ηn(β−1u). Let n≠m. We see from (9) that

Let δn,m=1 if n=m and δn,m=0 if n≠m.

Proposition 3.4. The random variables {Φkn} are orthogonal, that is

Proof. We have

Let k=l. We have

The Karhunen–Loève expansion is represented as follows: see Refs. 22 and 23 for the Karhunen–Loève expansion.

Theorem 3.2. We have

Theorem 3.2 tells us a proposition.

Proposition 3.5. For any m, we have

Proof. As N→∞, we see that

4. Stochastic Integrals with Respect to Momentum

Let −∞<−A≤a<b≤A<∞. Subdivide [a,b] as

Definition 4.1. If the quadratic mean limit of S(g,Δn) exists as |Δn|→0 and is independent of the choice of {Δn} and, for each Δn, is independent of the choice of {ỹni}, then the limit is denoted by

We introduce two half planes

Lemma 4.1. (i) If i≠j, then we have

(ii) If i=j, then we have

Proof. We first prove (i). We consider the case Ini,j⊂H+. Then

We next consider the case Ini,j⊂H−. Then we have

Finally, we prove (ii). We consider the case i=j. Then we have

Lemma 4.2. Then ∑1≤i,j≤kn|Dk(Ini,j)| is uniformly bounded regardless of how [a,b]×[a,b] is divided.

Proof. Let i≠j. From Lemma 4.1(i), we see that there is M1>0 such that

Through this paper, we use “piecewise continuous” as the following meaning:

Definition 4.2. Let a1,…,an be discontinuous points of g(y) on (a,b). For each interval [ai−1,ai], we define a function ği(y) by

Theorem 4.1. If g(y) is piecewise continuous on [a,b], then the integral ∫bag(y)dWky exists as a quadratic mean limit.

Proof. Let n>m. Since Δn⊃Δm, we have

The following theorem is obvious. The proof is omitted.

Theorem 4.2. If f and g are {Wky}-integrable, then c1f+c2g is {Wky}-integrable and

We show one lemma to prove Proposition 4.1. The proof is omitted.

Lemma 4.3. Let Xn and X be random variables and suppose supnEX2n<∞. If Xn converges to X in quadratic mean, then

Proposition 4.1. Let [a,b]⊃[aj,bj] for j=1,2. If f(y) and g(y) are piecewise continuous on [a1,b1] and on [a2,b2], respectively, then we have

Proof. We have

Theorem 4.3. If g(y) is of class C1, then

Proof. From Theorem 4.1, we see that g is {Wky}-integrable. For the partition Δn, we take

5. Representation Through OU Type Processes

Stochastic integrals based on {Zy} are represented in terms of Wky.

Theorem 5.1. Let −∞<a<b<∞. If g(y) is a function of class C1, then

In order to prove Theorem 5.1, we prepare a lemma.

Lemma 5.1. For any function g(y) of class C1, we have

Proof. We have

Now we prove Theorem 5.1.

Proof. Proof of Theorem 5.1

Since {Zky}, k=0,1,2,…, are independent, the integrals

Theorem 5.1 is also represented as follows:

Theorem 5.2. Let −∞<−A≤a<b≤A<∞. If g(y) is a function of class C1, then

Proof. From Theorems 3.2 and 4.3, we obtain that

6. Stochastic Complex Integrals

In this section, z is any complex number and represented as z=x+iy, where x and y are real numbers. Furthermore, z=x+iy∈ℂ is identified with (x,y)∈ℝ2. Hence, we often use the representation g(x,y) instead of any complex function g(z). Only in this section, g is a complex-valued function. A curve Λ is represented as a function

Definition 6.1. If Q(g,Δm,Λ) converges in quadratic mean as |Δm|→0, and if the limit does not depend on the choice of the sequence {Δm}, then the limit is denoted by

To show quadratic mean convergence of stochastic integrals, the following criterion is useful. See Ref. 22.

Lemma 6.1. The Loève criterion

The random variable sequence Xn converges in quadratic mean if and only if E[XmˉXn] has a finite limit, when mand n tend to infinity independently of each other.

Remark 6.1. For any z∈ℂ, we denote by ˉz the complex-conjugate of z. Hence, ˉXn means the complex-conjugate of Xn.

The following lemma is known as the Mercer’s theorem. See Refs. 24 and 25.

Lemma 6.2. In our setting, we have

For any random variable X, the norm of X is defined by

Lemma 6.3. Suppose the length of Λ is finite. If g is continuous on ˜D, then

Proof. We obtain from Proposition 3.5 that

Lemma 6.4. Suppose the length of Λ is finite. If g is continuous on ˜D, then

Proof. We have

Theorem 6.1. Suppose the length of Λ is finite. If g is continuous on ˜D, then the integral ∫Λg(z)Wk(y)dy exists as a quadratic mean limit, which is represented as

Proof. From Lemma 6.2, we see that

Definition 6.2. We define

We prepare two lemmas.

Lemma 6.5. Suppose the length of Λ is finite. Let Hm(t) be a complex-valued random variable sequence. If

Proof. There is δ>0 such that

Lemma 6.6. Suppose that a random function Hm(t) on [0,1] is defined as follows:

Remark 6.2. In the case where

Proof. Let t∈(tmi−1,tmi]. We have

Theorem 6.2. Suppose the length of Λ is finite. If g is of class C1 on ˜D, then the integral ∫Λg(z)dWky exists as a quadratic mean limit, which is represented as

Remark 6.3. If g is continuous on ˜D, the integral ∫Λg(z)Wk(y)dx exists as a quadratic mean limit, which is represented as

Proof. Let Δg(z(tmi))=g(z(tmi))−g(z(tmi−1)). We have

Finally, we introduce line integrals with respect to Zky, which is not assumed that Λ is closed.

Definition 6.3. We define

Proposition 6.1. Suppose the length of Λ is finite. If g(z) is of class C1 on ˜D, then the integral ∫Λg(z)dZky exists as a quadratic mean limit and

Proof. We see from (1) that

We do not assume that Λ is closed. Let g be a function of class C1 on ˜D and let g1 and g2 be the real part and the imaginary part of g, respectively. By virtue of Proposition 6.1, we have

Theorem 6.3. Suppose the length of Λ is finite. If g is of class C1 on ˜D, then

Proof. Proposition 6.1 tells us that almost surely

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates the referee’s comments for improving the paper.

Competing Interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Contribution

This work has been done alone. The author read and approved the final paper.