SINGAPORE ENGAGES THE BELT AND ROAD INITIATIVE: PERCEPTIONS, POLICIES, AND INSTITUTIONS

Abstract

This article argues that Singapore, courtesy of its strong state capacity and long-standing connections with China, has promoted effective polices and coordinated mutually reinforcing institutional mechanisms in engaging with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While some of these institutions predate the BRI, they have been continuously enhanced or modified to meaningfully foster Singapore-China cooperation. In certain cases, new institutions have been created to fulfill specific demands the existing institutions cannot adequately serve. These two types of institutions not only complement each other but also promote cooperation between the bureaucrats, politicians, transnational corporations, government-linked corporations, small- and medium-sized private firms and business associations. The article also illustrates the flexibility of the ‘networked state’ in formulating collaborative ties linking key international and domestic actors, demonstrating how a small state like Singapore can partner China effectively and deepen its strategic importance to the BRI to enhance its own strategic and economic interests. Lastly, the article highlights the two key conditions in BRI-related nations for their successful engagement: the existence of mutual interests between China and a counterpart nation bolstered by conducive perceptions and policies, and the institutionalization of competent mechanisms to materialize and operationalize these interests.

1. Introduction

Since its ‘Reform and Opening-up’ policies in 1978, China has experienced rapid growth, emerging as a prominent player in the global economy. It not only boasts of a large domestic consumer market but also has become a key foreign direct investment (FDI) contributor in the international arena since the early 2000s (Lim, 2017). Its stature has been elevated even further after the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping in late 2013. Revolving around five major priorities, infrastructure connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, policy coordination and connecting people, the BRI has become China’s foremost diplomatic and economic strategy in engaging with neighboring countries and beyond since 2013 (Xi, 2014; Zhao, 2020).

Six years after the BRI’s promulgation, there remains relatively little research on how (small- to medium-sized) states, such as those from Southeast Asia which occupies a key place in the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, engages with the BRI in advancing their own national interests (cf. Liu and Lim, 2019; Tong and Kong, 2018; Kratz and Pavlićević, 2019; Khoo, 2019; Teo, EC, 2019; Ba, 2019). Much of the existing analysis has focused almost exclusively on the interests and strategies of Chinese political and economic actors (see Liou, 2014; Yoshimatsu, 2018; Beeson, 2016). Extending Liu and Lim’s (2019) as well as Kratz and Pavlićević’s (2019) work on Malaysia and Indonesia, respectively, this article studies how a small (yet important) state such as Singapore manages its interactions with China as well as the BRI by skilfully incorporating domestic political economy factors with China’s growing presence in the region. Going beyond a macro-level analysis, it adopts a mesoscale perspective to take into account diverse economic, political, societal interests, and more importantly, the fluid interplay among these factors. From a theoretical point of view, this article adds depth to the concept of the ‘networked state’. Capturing the experience of Singapore, it reframes the hitherto dominant nation-state framework in the existing literature, moving the scholarship toward one which recognizes the multiple poles of power (beyond the nation-state) that have emerged since the liberalization of the 1980s.

With the above as a backdrop, this article addresses the following questions: how does Singapore — both the government and business groups — perceive the BRI and its opportunities (as well as challenges)? What are their respective policies and stances toward the BRI? What are the (pre-existing and new) institutions established to facilitate their objectives and what are the outcomes of these engagements? What are the implications of the Singapore experience in engaging the BRI for a broader understanding of the complex and varied reactions to this ambitious initiative that is reshaping the regional and global orders?

We argue that Singapore’s strong state has allowed it to promote effective policies and to create and coordinate mutually reinforcing institutional mechanisms in engaging with China. Some of these institutions predate the BRI but have been continuously enhanced to more meaningfully foster Singapore-China cooperation. In certain cases, new institutions have been created to fulfill specific demands the existing institutions cannot adequately serve. These two forms of (transnational) institutions complement each other, coordinating resources among the bureaucrats, politicians, transnational corporations (TNCs), government-linked corporations (GLCs), small- and medium-sized private firms and business associations.1 The Singaporean approach sheds light on a potentially new model of transnational governance as well as economic strategy. With a cohesive, strong ‘networked state’ at its core, key actors can be mobilized to formulate effective, broad-based and sustainable partnerships. Although this form of governance is occasionally interpreted as top-down and rigid, the reality is far more multidimensional. As the rest of the article shall demonstrate, Singapore’s closely coordinated and highly integrated governance style is especially useful in mediating cross-border resource exchange vis-à-vis other economies (in our case, China).

The next section unpacks the literature on Singapore’s capitalist development and state-society relations. It underscores the need to be sensitive to the city-state’s politics, in which a strong, efficient state has governed since its independence in 1965. The longevity of the incumbent administration has in turn allowed it to foster collaboration (rather than confrontation), especially in dealing with a prominent economy such as China. The article then puts forth a conceptual framework to make sense of how major domestic players interact with each other and how they contribute to exchanges of resources between Singapore and China. This is followed by an analysis of the perceptions of these key players toward the BRI and how they have engaged the initiative. Subsequently, the article presents the main institutions responsible for fostering Singapore-China collaboration, particularly since the BRI’s inception. The penultimate section concludes with a discussion of the main findings and suggests avenues for future research.

2. Literature Survey

As a city-state with limited natural resources, Singapore has to rely on international trade and investment to power its economy. The loss of the enlarged Malaysian market during Singapore’s separation from the former in 1965 only heightened the reliance on the international environment. However, what is generally less well-understood of this account is the institutional features with which Singapore manages its economy in navigating the peaks and troughs of the global economy. Singapore’s engagement with the international economy (and by extension, that of China) can be conceptualized under three interrelated spheres — economy, politics and state-society relations.

Singapore has witnessed continued governance from a single party, the People’s Action Party, since 1959, even before its Independence. The longevity of the incumbent has allowed it to shape state-society relations to one which is pro-growth and long term in nature (Low, 2005; Tan and Bhaskaran, 2015). Coupled with its small size, this feature provides the state the advantage of quick, centralized policy implementation. In addition, the state’s ‘two-legged’ policy of attracting foreign TNCs and cultivating its own GLCs has reduced its reliance on the domestic private sector during the immediate post-Independence decades (Tsui-Auch, 2004). Unlike the capital- and technology-intensive TNCs and GLCs, these firms were perceived to be ‘dragging the economy down in terms of low productivity and intensive use of labor resources in the wake of severe labor shortage at that time’ (Chan and Ng, 2000, 294). Consequently, these firms were either displaced or had to subcontract their services to the foreign TNCs and/or the GLCs (Low, 1990). The relative weakness of the domestic private firms has in turn lead to an unusual outcome — they possess little power to influence public dialogue and policymaking, allowing the state to push policies that are beneficial for the entire society but which require a longer-than-normal horizon. The two-legged policy worked well as Singapore enjoyed robust growth in its post-Independence decades, joining the ranks of Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong as Asia’s first-tier tiger economies (Shin, 2005).

However, this model was interrupted by a worldwide recession in the mid-1980s. To counter the impasse, the state came up with a regionalization strategy, in which firms are encouraged to venture into markets adjacent to Singapore, including but not limited to China. The goal is to develop a second market to augment Singapore’s small domestic market (Tan and Yeung, 2000; Saw, 2014). Both marking a break from and building on its hitherto two-legged policy, the state began to more actively drawing in the (small- and medium-sized) domestic private firms to complement the TNCs and GLCs in its regionalization efforts (Dahles, 2008; Tan and Bhaskaran, 2015).

This strategy has also been bolstered by concrete state support. One of the landmark projects of this sort is the Government-to-Government (G-to-G) Suzhou Industrial Park, China. This project was conceptualized in 1992 to attract foreign firms (including those from Singapore) into Suzhou to spearhead industrialization, as part of Singapore’s effort in sharing its experience in industrial development with China.2 Encompassing 70km2 and covering industrial, commerce and residential components, Suzhou Industrial Park is designed to attract a total investment of US$20 billion. The township is to support a population of 600,000 and employ 300,000 people upon completion (Lye, 2014; Zeng, 2019).

The success of the Suzhou Industrial Park has since deepened bilateral cooperation. In November 2003, Singapore-China cooperation was put on an institutionalized basis when the high-level Joint Council for Bilateral Cooperation (JCBC) was launched by then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong and then Premier Wen Jiabao (Saw, 2014). The JCBC, co-chaired by the Deputy Prime Ministers of China and Singapore, allows the two countries to review annually the state of existing relations and to identify new areas of collaboration. Its inception has provided a regular and systematic platform for political leaders, bureaucrats and businessmen from both countries to network and cooperate on ventures.

In addition, Singapore’s (ethnic Chinese) business associations function as important non-governmental resources in promoting Singapore-China ties, supplementing the top-down approach of the state (Liu et al., 2016). These business associations play an integral role in the following aspects: collecting business information, protecting commercial credit, organizing relevant trade activities, providing collective bargaining ability and reducing transaction costs. Liu et al. (2016) also illustrate that these organizations — by deploying their social capital and knowledge of the Southeast Asian market — can become suitable conduits in promoting the BRI in the region, not least in deepening the understanding of the public about the effectiveness of the BRI. This ‘whole-of-nation’ approach has retained its relevance since, playing an equally (if not more) important role after the launching of the BRI.3

Notwithstanding its good relationship with China, Singapore has managed to maintain neutrality in its ties with other countries, sometimes serving as an effective intermediary between China and the West. Even in view of the escalating tension between the United States and China, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that the city-state would resolutely stick to its policy of maintaining good ties with both countries (Sim, 2019). His stance is ultimately centered on economic reasoning rather than zero-sum state-state contestation, which can potentially be ruinous. Enriching this perspective is Ba’s (2019) research on the strategic narratives deployed by Singapore’s policymaking community. She demonstrates the adept construction of a historical narrative of a ‘special relationship’ and underlined by Singapore’s support for key Chinese priorities and critical moments in China’s historical development. This narrative has provided Singapore an important foreign policy tool with which to manage its bilateral relations with China. Singapore’s position is also buttressed by its adherence to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). For example, in dealing with the geopolitical tension arising from the South China Sea disputes, Singapore has always maintained that the disputes be resolved based on international law. And it has consistently reiterated that freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and a united ASEAN are the country’s national interest (Tong and Kong, 2018).

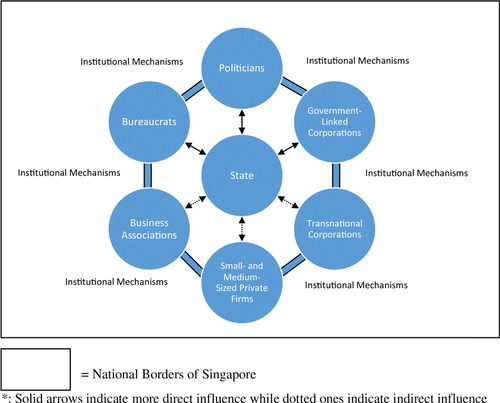

3. Conceptual Framework: Institutionalization of the Networked State

Synthesizing and going beyond the above literature, this article aims to account simultaneously for the agency of several key actors by presenting a conceptual framework to analyze how they interact with the external world (see Figure 1). Figure 1 illustrates seven of the most critical players in Singapore, and how they simultaneously contribute to the exchange and allocation of resources between Singapore and the international economy (in this article, China). Marking a break from the predominant nation-state framework, which remains important in its own right, Figure 1 recognizes the heightened pace of cross-border movements of people, ideas and capital, especially since the rise of neoliberalism after the 1980s (Aalbers, 2013; Castells, 2000; Wolf, 2004; Carroll and Jarvis, 2017). According to Ohmae (1995), this means that the controlling mechanisms over society are no longer the exclusive purview of the state. In other words, there exist substantially more poles of power in shaping economic transformation.

Figure 1. Institutionalization of the Networked State: The Case of Singapore

Source: By the authors.

However, Singapore’s unique development experience (i.e., the uninterrupted governance of a single dominant party and the initial ambivalence toward its small- and medium-sized domestic private firms) suggests that the state is likely to play a larger-than-usual role in governance affairs.4 What is more important here is to recognize, in addition to the continued prevalence of the Singaporean state, the three dimensions of network — as a relational entity; an interconnected node and a collective layer of spatially constructed ties (Liu, 2018). Here the state is to be conceptualized as a ‘networked state’, communicating with various key players through existing and new institutional mechanisms. These institutions are important because they can coordinate and manage the often diverse interests and agendas of key stakeholders, establishing an effective and broad-based partnership (Liu, 2018). This highly coordinated governance style is critical in mediating policy diffusion and cross-border resources (e.g., FDI and trade of goods and services) exchange vis-à-vis other economies.

4. Perceptions, Policies and Strategies: State-Society Collaboration

4.1. Politicians, bureaucrats and GLCs

Singapore is one of the first countries to publicly express support for the BRI. During the 11th China-ASEAN EXPO Opening Ceremony, held in Guangxi on 16 September 2014, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong affirmed China’s efforts in playing a bigger role in the international as well as regional setting. Some of the initiatives he explicitly supported were the upgrading of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement (FTA), establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and promotion of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, 2014).5

To foster cooperation through multilateral channels, Singapore, as early as 24 October 2014, signed in Beijing an intergovernmental memorandum of understanding (MOU) with 20 other countries, earmarking itself as a first-mover in establishing the AIIB, a new multilateral development bank commonly viewed as the financing arm of the BRI (Tan, 2014).6 The signatories of the MOU then took part in negotiations for the AIIB’s Articles of Agreement. The countries which subsequently signed and ratified the Articles of Agreement will then officially become founding members of the AIIB. On 29 June 2015, less than a year after the signing of the MOU, the AIIB took a crucial step forward with 50 countries, including Singapore, signing off on its charter (Kor, 2015). Contributing US$250 million toward the US$100 billion capital of the AIIB, Singapore enjoys a 0.2585% stake in the bank, giving it 0.4365% voting rights. According to Singapore’s representative, the then Senior Minister of State for Finance and Transport Josephine Teo, this move was ‘to support further economic development in the region, by working with all founding members to build up the AIIB as a first-class multilateral financial institution’ (Kor, 2015).

Building on its efforts on the multilateral front, Singapore has also implemented several bilateral policies to strengthen bilateral cooperation. During the First Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, held on 14 and 15 May 2017 in Beijing, Singapore and China signed another MOU (Ministry of National Development, 2017; Koh, 2017). The MOU subsequently was fine-tuned, pinpointing to and promoting collaboration in three areas: infrastructure connectivity, project financing and joint undertaking of projects in third countries.

Firstly, in promoting infrastructure connectivity, both sides shall reinforce existing efforts to deepen the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative, a G-to-G project launched by Xi Jinping during a state visit to Singapore in November 2015.7 The Chongqing Connectivity Initiative is conceptualized as an important part of China’s drive to reduce the income disparity between its wealthy coastal and poor inland and Western regions, promoting greater trade and investment in the regions and provinces of Guizhou, Guangxi, Ningxia and Gansu via Chongqing. At a broader level, the initiative is to more thoroughly connect the overland Silk Road Economic Belt with the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. This will offer a shorter and more direct trade route between Western China and Southeast Asia. Potentially, it can enhance cross-border trade flows and help to catalyze the economic development of both regions, thud directly benefiting Singapore as a key transport and logistics hub in the Asia-Pacific. Departing from conventional approaches in which investment and trade effort is targeted at a specific location such as an industrial park or a city, the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative is an open platform, encouraging more users (regardless of nationality) to build up economies of scale, ultimately reducing per unit cost (Lim, 2018).

Secondly, in the financing of BRI projects, both sides view the infrastructure-oriented outlook of the BRI as an opportunity to bridge Asia’s persistent infrastructure shortfall, with the ADB projecting in 2017 that Asia needs to invest $26tn by 2030 to resolve a serious infrastructure shortage (Pell and Mitchell, 2017). The overarching objective is to make currently unfeasible projects more bankable, thereby attracting funding from the private sector. This is an area where Singapore is not a direct beneficiary of housing an infrastructure project, but plays an important role in partnering Chinese stakeholders (e.g., banks and construction firms) intending to internationalize their operations. As a major center of global and regional finance, approximately 60% of infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia obtain their finance and advisory services from Singapore-based financial institutions. Beyond financing, Singapore also houses a full suite of professional service provides that are necessary to bring infrastructure projects to fruition. This ecosystem is equally conducive for Chinese banks intending to raise credit and debt for their clients. For example, risk management solutions (e.g., risk pooling, especially for larger and more complex infrastructure projects) pertaining to the needs of Chinese insurers and reinsurers are in the process of being formulated. Some of the noteworthy success stories are the Bank of China (Singapore branch) and the China Construction Bank (Singapore branch). In 2017 alone, they issued US$600 million and RMB 1 billion worth of BRI-themed bonds respectively (Ministry of National Development, 2017).

Thirdly, Singaporean and Chinese firms are encouraged to forge partnerships to undertake joint projects, in addition to collaborating on human resource development in third countries. Tapping into the growing ambitions of Chinese firms ‘Going Out’ of their home economy, Singapore offers strong, mature linkages for the former to venture into Southeast Asia and beyond. For Singapore, this move dovetails with its goal of developing markets adjacent to it, augmenting its small domestic economy. Although this initiative started in the mid-1980s, it has continued to receive attention from policymakers. Singapore’s capital-intensive GLCs are examples of how potentially win-win partnerships can be forged. Surbana Jurong — one of the top GLCs in design, engineering and consultancy services — has set up a joint venture with China Highway Engineering Consulting Corporation in 2017.8 The latter specializes in the construction of complex, large-scale transport infrastructure (often in challenging landscapes), but has only entered the Southeast Asian market relatively recently. This partnership essentially promotes a division of labor — China Highway Engineering Consulting Corporation brings to the table its technical expertise while Surbana Jurong (through itself and/or its affiliates) offers tacit knowledge of the different Southeast Asian economies. Despite its size, Surbana Jurong appears to network fairly frequently with key business associations/federations in Singapore, suggesting that there is likely to be some degree of cooperation between them.9

4.2. Small- and medium-sized private firms, TNCs and business associations

Although generally lacking capital and technology (relative to the GLCs and TNCs), Singapore’s small- and medium-sized private firms are important players in Singapore’s dovetailing with the BRI. As a result of their decades-long experience operating in China and Southeast Asia, they have developed some innovative capabilities and place-specific cultural nuances, competitive advantages that are difficult to replicate. In addition, they are often able to match (or even usurp) the GLCs and TNCs in reacting to market opportunities primarily because of their small size and shorter chain of command. Such features make them ‘natural partners’ for Chinese firms entering the region (especially those lacking experience outside China) as well as Western and Japanese TNCs eager to tap into the opportunities opened up by the BRI.

Their proactiveness can be witnessed in how swiftly the business associations/federations are in associating their major events and forums with the BRI to create greater awareness, generate discussions and build mindshare of the BRI with its members. Examples of such Singapore associations are Business China (a semi-official organization established in 2007 by the Singapore government and business sector in engaging China), Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce (SCCCI) and Singapore Business Federation (SBF), among others.10 Beyond business-related discussion, these business associations have also played a significant role in strengthening cultural and people-to-people exchanges with China’s business chambers (Enterprise Singapore, 2017). To this end, the SBF’s actions are particularly noteworthy.11 The SBF and Lianhe Zaobao, the Chinese language flagship newspaper of Singapore Press Holdings, jointly launched a BRI-themed portal on 8 March 2016 (Singapore Business Federation, 2016). The portal is Southeast Asia’s first bilingual (Chinese and English) comprehensive website to focus on the BRI, offering a Southeast Asian perspective and promoting BRI-related business activities between Singapore, Southeast Asia and China. It presents an overview of the BRI, its latest development, news, business opportunities, analyses, commentaries and a calendar showcasing activities related to the BRI within the region.

The tentative sentiment of the small- and medium-sized private firms can be gauged from the National Business Survey 2017/2018 (Singapore Business Federation, 2018).12 The survey shows that about two in five firms feel positive about BRI. More than half of the firms surveyed are also looking for updates on the latest development on the BRI (62%) as well as market intelligence and research (54%). About two in five of these firms are interested to embark on or are already involved in BRI projects in Thailand (40%), Vietnam (40%) and Singapore (38%). When polled on the industrial activities that they are most interested in to participate under the BRI, as many as 34% selected industrials, transportation and logistics. The second most popular activity is technology (29%), followed by professional services (26%), financial services (19%) and others (18%).

For the TNCs, their perception and overtures to Singapore’s stance toward the BRI are harder to determine as they tend to be driven by firm- and industry-specific logic, in addition to unexpected events such as natural disasters.13 However, the early 2019 decision by British appliance maker Dyson to relocate its headquarters to Singapore can shed some light on how a brand name TNC is responding to the city-state’s actions in managing the BRI. According to Jim Rowan, Dyson’s Chief Executive Officer, the move underlines the importance of the Asian market, where the firm sees the biggest opportunities for growth in the future (BBC, 2019). Moreover, analysts point to Dyson’s preference to operate closer to its suppliers (most of whom are Asia-based) and Singapore’s multiple FTAs with major economies, in addition to ‘policy clarity which will not see manufacturing operations being disrupted by policy flip-flop’ (Ng, 2019).14

5. Institutional Mechanisms: Continuity and Change

Singapore’s engagement with the BRI can be broken into two broad institutional mechanisms: existing ones and new ones. Utilizing existing institutions, the former has been enhanced and updated to more effectively engage with the challenges and opportunities arising from the BRI. For the latter, they have been established to fill a specific niche, which the existing institutions cannot adequately serve. These two forms of institutions complement each other, collectively coordinating resources among the bureaucrats, politicians, TNCs, GLCs, small- and medium-sized private firms and business associations (see Figure 1).

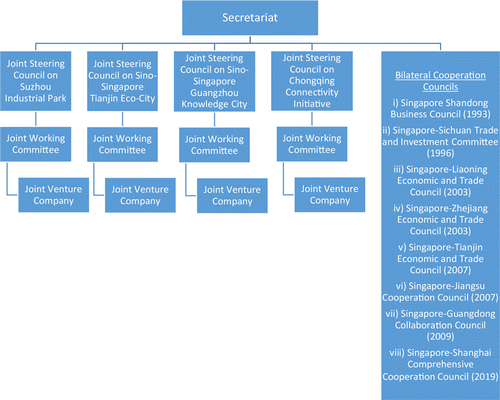

Singapore’s deep experience in dealing with China means that it has developed critical institutional mechanisms to foster cooperation with the Chinese, even prior to the BRI’s announcement. The aforementioned JCBC ranks as the most prominent and overarching institution in managing Singapore-China relations in the economic and social arenas (see Figure 2). Conceptualized in 2003, it has continually been revitalized to reflect the latest development between the two economies. This is reflected in the ways through which key bilateral cooperation councils linked to eight municipals and provinces are integrated under the JCBC. Seven of these councils have been formed prior to the BRI, with the earliest one established in 1993. In May 2019, the Singapore-Shanghai Comprehensive Cooperative Council was formed and parked under the JCBC.

Figure 2. Organizational Structure of the Joint Council for Bilateral Cooperation

Source: Compiled by the authors based on publicly available data.

Taking a ‘whole-of-nation’ approach, these councils are co-chaired by top officials of both Singapore and China. Reflecting on the renewal of Singapore’s political leadership, it is fitting that its next crop of politicians in Singapore (known commonly as the fourth-generation leaders) is co-chairing several of these bilateral cooperation councils (Au-Yong, 2018). Some of the top names include Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance Heng Swee Keat, Minister for Trade and Industry and Minister-in-Charge of the Public Service Chan Chun Sing, Minister for Education Ong Ye Kung, Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli, Minister for Manpower and Second Minister for Home Affairs Josephine Teo and Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Ng Chee Meng (see Table 1). These sub-national councils provide additional avenues to bureaucrats, politicians and businessmen from both sides to cooperate on a more intimate level, moving beyond the strategy set at the national level.15

| Bilateral Cooperation Councils | Co-Chairmen (Singapore) | Co-Chairmen (China) |

|---|---|---|

| Singapore Shandong Business Council | Chee Hong Tat, Senior Minister of State for Trade and Industry and Senior Minister of State for Education | Ren Airong, Deputy Governor of Shandong Province |

| Singapore-Sichuan Trade and Investment Committee | Ng Chee Meng, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office | Li Yunze, Deputy Governor of Sichuan Province |

| Singapore-Liaoning Economic and Trade Council | Masagos Zulkifli, Minister for the Environment and Water Resources | Tang Yijun, Deputy Secretary of the Provincial Party Committee and Governor of Liaoning Province |

| Singapore-Zhejiang Economic and Trade Council | Sim Ann, Senior Minister of State for Communications and Information and Senior Minister of State for Culture, Community and Youth | Zhu Congqi, Deputy Governor of Zhejiang Province |

| Singapore-Tianjin Economic and Trade Council | Lawrence Wong Shyun Tsai, Minister for National Development and Second Minister for Finance | Zhang Guoqing, Mayor of Tianjin City |

| Singapore-Jiangsu Cooperation Council | Indranee Rajah, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office and Second Minister for Finance and Second Minister for Education | Wu Zhenglong, Governor of Jiangsu Province |

| Singapore-Guangdong Collaboration Council | Ong Ye Kung, Minister for Education | Ma Xingrui, Governor of Guangdong Province |

| Singapore-Shanghai Comprehensive Cooperation Council | Heng Swee Keat, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance | Ying Yong, Deputy Secretary of the Municipal Party Committee and Mayor of Shanghai Municipal Government |

The evolving nature of these councils is exemplified by the Singapore-Shandong Business Council (SSBC). Formed in 1993, it remains the oldest bilateral business council interlinking Singapore and China. Its original function was primarily to assist Singaporean and Chinese firms in locating business opportunities, exploring joint areas of cooperation and promoting the investment of Singaporean companies into Shandong. In the early years, the businesses targeted were mostly labor-intensive, ranging from real estate to logistics management.

As the Chinese economy grew more sophisticated, the SSBC has expanded to cover more high value-added activities. In 2014, Li Qun, then Party Secretary of the Qingdao Municipal Party Committee, proposed to former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, during the latter’s visit to Qingdao (a municipal under Shandong), to deepen cooperation with Singapore in the financial industry (Ruiji Touzi, 2014). Such a proposal, while reflecting on the domestic politics and economic logics of the subnational Chinese governments’ engagement in the BRI (Ye, 2019), resonates with Singapore’s ambition to play a bigger role in the BRI, especially in coordinating financial exchange between China and other BRI recipient states. To this end, Qingdao established a pilot zone in the same year to more effectively foster its goal of deepening financial cooperation with Singapore. In 2018, the ‘Qingdao Wealth and Financial Management Comprehensive Reform Pilot Zone Overall Plan’ was formally legislated by the State Council of China.

The SSBC’s evolution suggests that it is keeping pace with the development of both the Singaporean and Chinese economies. Providing business information about Shandong (and the rest of China), its goals during the 1990s and early 2000s were tailored to meet Singapore’s regionalization strategy and China’s urgent need for investment during its opening-up phase. In recent times, the SSBC has rejuvenated itself to better support the ambitions of Chinese firms internationalizing their operations, and the Singaporean firms eager to play a part in the BRI. In addition to providing trade and investment information, the SSBC has deepened its expertise to provide more targeted support to the aspirations of Shandong-based firms (e.g., Qingdao’s desire to shore up its expertise in financial management) and the competitive advantage of Singaporean firms (e.g., expertise in high value-added manufacturing and financial services).16

Apart from the eight bilateral councils, the JCBC also directly monitors key G-to-G projects such as the aforementioned Suzhou Industrial Park through the setting up of project-specific joint steering councils (see Figure 2). These joint steering councils are co-chaired by top politicians of Singapore and China, respectively. It also brings together various ministries and agencies from both sides to facilitate and coordinate development. Below the joint steering committees are the joint working committees that focus more on operational issues (Lye, 2014). They in turn monitor progress of the Singapore-China joint venture companies, which are responsible for the physical development of the project and their commercial viability. One of the joint steering committees’ unique feature is the manners in which GLCs are mobilized by the Singaporean state in the establishment of joint venture companies in these large G-to-G undertakings. A legacy of Singapore’s two-legged economic policy, the GLCs are mobilized to partake in deals entailing a long gestation period and huge capital outlay (at least at the outset), thereby overcoming potential lack of investment from the private sector. The longer-than-usual horizon of the GLCs, coupled with the political continuity of both the Singapore and Chinese states, creates a stable, predictable environment for which accompanying investment from other TNCs and small- and medium-sized private firms can be attracted.

More importantly, the streamlined, tri-level structure of these joint steering councils promotes frequent interactions — both at the institutional and individual levels — among bureaucrats, politicians, TNCs, GLCs, small- and medium-sized private firms and business associations, enhancing Singapore-China bilateral ties. This can be seen in the continuity by which G-to-G industrial parks/urban centers are constructed. For the Suzhou Industrial Park, it was conceptualized in the early 1990s, an era in which China sought to learn from Singapore in attracting FDI to develop its then backward economy. The Tianjin Eco-City was launched in 2008. Following three decades of rapid growth, several Chinese cities were beginning to suffer severe cases of pollution. Both Singapore and China decided to use this project as a model for sustainable, green development for other Chinese cities, with the main focus on environmental conservation, resource and energy conservation and sustainable development (Flynn et al., 2016; Caprotti, 2014). In 2010, the Sino-Singapore Guangzhou Knowledge City was launched. This project represented both countries’ increasing awareness of the need to tap into the highly competitive and globalized knowledge economy. If executed well, it can further the progress of China’s emerging niche in highly knowledge-intensive industries such as artificial intelligence and high-technology manufacturing, with Singapore reaping the rewards as a facilitator.

In November 2015, the aforementioned Chongqing Connectivity Initiative was launched. This project is the highest profile collaboration between Singapore and China since the BRI was announced in 2013. Unlike the previous G-to-G collaboration, this project is not geographically bound. Epitomizing the ideals of the BRI, this project is also more ambitious than the other Singapore-China projects thus far, aiming to enhance the connectivity of Chongqing within China itself and with the rest of the world (Chong, 2019). Singapore’s expertise in infrastructure planning and logistics development would be useful for this project. During the 14th JCBC, held in Singapore on 20 September 2018, the then Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean announced that Singapore and Chongqing companies have formed joint ventures — the Sino-Singapore Chongqing Connectivity Solutions (SSCCS) and the Sino-Singapore (Chongqing) DC Multimodal Logistics (SSDCML) — to drive the new trade route’s development (Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, 2018).

One of the most important new institutions with regards to the BRI is the establishment of Infrastructure Asia in October 2018. This new government agency, set up by Enterprise Singapore and the Monetary Authority of Singapore, serves as a one-stop platform to facilitate regional infrastructure collaboration. Given the central role of infrastructure provision in the BRI and the broader need to address infrastructure demand in the region, Infrastructure Asia’s establishment is timely. In particular, it tackles the issue of financing by making large, long-term infrastructure projects more bankable and investible.

According to Seth Tan Keng Hwee, Executive Director of Infrastructure Asia, the savings rate of (Southeast) Asia in relation to the demand for investment in infrastructure is sufficient to meet its demand (see also Khor et al., 2019). However, one of the prime reasons infrastructure in the region remains undersupplied is because projects are not bankable or they do not fit the needs and expectations of investors (Oxford Business Group, 2018). For Infrastructure Asia, it offers solutions to make projects more bankable and investible such as tweaking the financing structure and standardizing contracts to shorten the preparation and negotiation phases of a project. In addition, Infrastructure Asia leverages on Singapore’s diplomatic neutrality, familiarity with the other regional economies, connectivity to world-class firms as well as institutions and successful development experience (Oxford Business Group, 2018).

Some of the more prominent partners Infrastructure Asia has signed MOU with are the aforementioned SBF and the World Bank Group (Infrastructure Asia, 2019a). With the MOU, Infrastructure Asia is slated to hold quarterly briefings with the SBF to market and match its members to relevant business opportunities. For the World Bank Group, it will leverage its own and Infrastructure Asia’s networks and expertise to drive knowledge building and exchange within Asia and to help countries strengthen capacities for infrastructure project structuring, financing, implementation and operation (Infrastructure Asia, 2019b).

Despite its recent establishment, Infrastructure Asia has initiated and facilitated the formation of the China-Singapore Co-Investment Platform, bringing together the aforementioned Surbana Jurong and Silk Road Fund (a medium- to long-term investment fund set up by China’s central government in 2014 in financing the BRI projects). Under the agreement, both partners will set up a co-investment platform worth US$500 million that is primarily focused on greenfield infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia. The partners expect to invest about US$500 million over the next few years, with each partner investing in principle equal amounts in the projects (Surbana Jurong, 2019b). Investments of the platform could take various forms, including equity and debt. For Infrastructure Asia, it not only brought Surbana Jurong and Silk Road Fund together due to their complementary capabilities and common intent of investing in Southeast Asia but also facilitated Singapore’s ambition of cooperating with China in projects in third countries (in this case, other Southeast Asian economies).

At an on-the-ground level, there is a growing perception that both old and new institutions have interacted to forward Singaporean interests, especially in third countries (with the support of the Chinese). Owned and managed by the Teo family, Pacific International Lines has invested an initial 1 billion yuan (S$206 million) to build an integrated logistics park in Nanning, the capital city of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in 2017 (Straits Times, 2017). Present at the launching ceremony was Minister for Trade and Industry and Minister-in-Charge of the Public Service Chan Chun Sing. In a short opening address, he noted that the park could play a key role in supporting the Southern Transport Corridor, part of the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative. When ready, the Southern Transport Corridor could offer a more cost-effective way for companies in Southeast Asia to go into western China and vice versa (The New Paper, 2017). This sentiment is shared by Pacific International Lines managing director Teo Siong Seng who declared: ‘Guangxi does a lot of border trade with Vietnam, and many of the imported goods are sent to Guangzhou for processing. With this park, we hope to attract businesses to do some of the processing and packaging here’ (The New Paper, 2017).17 This project builds on and reinforces another Singaporean undertaking in Qinzhou City, Guangxi province, i.e., the new container terminal called Beibu Gulf-PSA International Container Terminal Co. Conceptualized in June 2015, this venture is spearheaded by a Singapore-China consortium. For Singapore, the project is pushed by PSA International (a GLC), supported by Pacific International Lines. On China’s side is the state-owned Beibu Gulf Port Group. When completed, the terminal will support the container trade growth in the region and serve the vast hinterlands of Guangxi, Sichuan, Chongqing and Hunan. It will also connect the region to key shipping routes linking China to Southeast Asian countries, East Africa and the Mediterranean (Lee, 2015).

At a broader scale, this ‘whole-of-nation’ approach has yielded substantial tangible economic outcomes for both countries. This can be interpreted from Singapore’s continued relevance to Chinese firms, relative to the other regional economies. Table 2 shows that from 2010 to 2018, Singapore has maintained (and even extended its lead in some years) its number one position in Southeast Asia for the attraction of Chinese FDI. Although there were fluctuations on a yearly basis, the general trend is for Singapore to garner about 50% of the total FDI inflow entering the region. However, the impact is less noticeable in bilateral trade promotion. Originally the second largest trade partner for China, Singapore began to move down one spot in 2014 following Vietnam’s aggressive push to promote trade ties with the Chinese (see Table 3). In 2015, Vietnam even became China’s largest trade partner in the region, usurping Malaysia (the hitherto incumbent). Nevertheless, when one accounts for Singaporean performance over the entire period surveyed, the trend is for it to mirror the movement of ASEAN’s bilateral trade. This implies that it is not losing out too much to its fellow regional economies. Put together, Singapore still is China’s largest source of FDI and third largest trade partner, maintaining its lead over far bigger economies such as Indonesia and the Philippines.

| Host Country | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore | 0.7 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 37.8 |

| Brunei | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 |

| Cambodia | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 4.0 |

| Indonesia | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 7.2 |

| Laos | 0 | 0.3 | — | — | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| Malaysia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 3.9 |

| Myanmar | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 5.0 |

| Philippines | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Thailand | 0.6 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.8 |

| Vietnam | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 5.3 |

| Singapore | Vietnam | Malaysia | Indonesia | Philippines | ASEAN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 5.9 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 26.0 |

| 2010 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 7.1 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 29.8 |

| 2011 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 8.3 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 33.9 |

| 2012 | 7.0 | 5.4 | 10.1 | 6.9 | 3.1 | 40.3 |

| 2013 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 10.6 | 6.7 | 3.6 | 44.4 |

| 2014 | 8.5 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 47.7 |

| 2015 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 45.3 |

| 2016 | 7.5 | 10.7 | 9.9 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 48.0 |

| 2017 | 7.7 | 14.1 | 9.7 | 6.5 | 4.7 | 52.5 |

| 2018 | 7.5 | 13.1 | 9.4 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 50.1 |

| 2019 | 9.8 | 16.6 | 12.6 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 64.1 |

6. Conclusion

By taking a step further of Liu’s (2018) postulation of the ‘networked state’ and its changing role in a transnational Asia, this article has underscored the need to reconsider the hitherto dominant nation-state framework in public governance and development studies. Admittedly, the greatly intensified pace of cross-border exchange of resources since the 1980s has meant the mushrooming of multiple poles of power in shaping governance and economic transformation. Nevertheless, Singapore’s unique development experience (i.e., the uninterrupted governance of a single dominant party and the initial ambivalence toward its small- and medium-sized domestic private firms) suggests that the state is to play a larger-than-usual role in governance affairs, not least in engaging with China. This can be witnessed in the more concerted attempt of mobilizing its cohort of small- and medium-sized private firms to counter the mid-1980s global economic downturn. A masterstroke in economic strategy, this move helped bolster Singapore’s presence in the economies adjacent to Singapore, especially China. It also enhanced Singapore’s previously dominant two-legged policy by injecting entrepreneurship of the small- and medium-sized private firms into the commercial power of the TNCs and GLCs, a point raised by Dahles (2008) and Tsui-Auch (2004).

More importantly, the above transformation demonstrates the flexibility of the ‘networked state’. From an initial ambivalence toward the small- and medium-sized private firms, the state has since formulated collaborative, broad-based ties among key domestic actors to engage the Chinese economy effectively. Singapore’s highly coordinated and closely integrated governance style can be witnessed in the institutions that were created before (such as the JCBC) as well as after the BRI’s inception (such as Infrastructure Asia). These two types of institutions not only complement each other but also promote cooperation between the bureaucrats, politicians, TNCs, GLCs, small- and medium-sized private firms and business associations. These institutions have been conceptualized at different stages of China’s economic growth. Although the Chinese economy has advanced considerably since its economic reforms started in 1978, Singapore — deploying its highly networked and mutually reinforcing governance model — has come in and partnered China at critical junctures of the latter’s progress. This approach is likely to maintain, if not deepen, Singapore’s strategic importance to the BRI (and by extension, China).

What then are the region-wide implications of this article? In a recent survey of Southeast Asian elites conducted by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies ISEAS (2019), titled The State of Southeast Asia: 2019 Survey Report, a rising China has received mixed responses from the region. Most respondents (45.4%) think ‘China will become a revisionist power with an intent to turn Southeast Asia into its sphere of influence’, with the second most prevalent view regionally (35.3%) being ‘China will provide alternative regional leadership in the wake of perceived US disengagement’. Less than one in ten respondents (8.9%) sees China as ‘a benign and benevolent power’. With respect to the BRI, close to half of the respondents (47%) think it ‘will bring ASEAN member states closer into China’s orbit’, and 35% acknowledges China’s for giving loans to provide ‘much needed infrastructure funding for countries in the region’. The overwhelming majority of the respondents (70%), however, opine that their government ‘should be cautious in negotiating BRI projects, to avoid getting into unsustainable financial debts with China’.

Our findings suggest that such fears are perhaps overblown. From its initial engagement with China during the ‘Reform and Opening-up’ era to the contemporary period, Singapore has consistently found avenues to cooperate with the Chinese, showing that mutual benefits can be gained through joint projects and bilateral tie-ups while preserving its sovereign interests. These interests, in the meantime, have been embedded through institutions including the governmental (e.g., JCBC), semi-official (e.g., Business China) and business associations (e.g., SBF and SCCCI), thus providing multiple avenues for exchanges of ideas, resources and effective implantation at both the national and local levels. The revitalization of existing mechanisms and establishment of new ones have provided impetus for both continuity and change. Through these shared interests and mutually reinforcing institutions, the states of both China and Singapore are essentially networked under the framework of the BRI. More critically, Singapore’s success thus far demonstrates that small states possess sufficient autonomy to manage the opportunities and challenges resulting from the BRI. Our article has also demonstrated how state-society collaboration (rather than confrontation) can be fostered in critical matters related to a rising China.

It is hoped that the framework put forth in this article as well as its arguments will stimulate future research, contextualizing this article’s framework and arguments in different settings. For example, Brunei — Singapore’s ‘twin’ in Southeast Asia — and its engagement with the BRI can be explored. Much like Singapore, Brunei boasts a small population size and promotes relatively open economic policies. Facing a slowing global economy, the Sultanate has also been actively courting Chinese capital to stimulate its economy. Another relevant economy to be studied is Malaysia, Singapore’s northern neighbot. Sharing similar colonial heritage with Singapore and boasting a similar level of economic output, Malaysia too has been attemping to forge closer economic ties with the Chinese, not least in recent years. We believe that such a study will contribute to the further exploration of the ways through which other Southeast Asian states have formulated their respective economic strategies in response to the BRI.

Acknowledgment

Research for this article has been supported by the MOE Tier-2 AcRf “Transnational Knowledge Transfer & Dynamic Governance in Comparative Perspective” (MOE2016-T2-2-087) and an SUG from Nanyang Technological University (Integrating through Mobility: Cross-border Migration and Transnational Networks between China, Japan and Singapore, M4081383). The authors are solely responsible for the views and any remaining errors in this article.

ORCID

Hong Liu  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3328-8429

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3328-8429

Guanie Lim  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9083-8883

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9083-8883

Notes

1 Within the context of this article, small- and medium-sized private firms are defined as those with annual sales not exceeding S$100 million and/or with employment not exceeding 200 people.

2 In its effort to reintegrate into the global economy, China launched its ‘Reform and Opening-up’ policies in 1978. The Chinese political leadership found in Singapore a useful reference to bolster its then backward economy (Lye, 2014; Liu and Wang, 2018; Teo EC, 2019).

3 See the subsequent sections for a more detailed elaboration of the JCBC and its functions.

4 Unlike the other Northeast Asian developmental states and economies (i.e., Japan, Korea and Taiwan), Singapore has continued to enjoy uninterrupted governance by a single party since the post-World War Two era. See Low (2003), Johnson (1982), Wade (2003), Amsden (2003), Carroll and Jarvis (2017), and Rahim and Barr (2019) for a critical review of the concept of the developmental state.

5 The BRI is composed of two main components: the Silk Road Economic Belt (connecting China to Europe by land through Central Asia) and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (connecting China to Europe by sea through Southeast Asia).

6 This view is not entirely true as its purpose is to support infrastructure financing in Asia. Although China is the AIIB’s largest shareholder with a 30.79% stake that will give it 26.56% voting rights and veto powers over major decisions, it is noticeably more egalitarian compared to the US-led World Bank and the Europe-led International Monetary Fund (Wilson, 2017; Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, 2019; Zhao, 2020).

7 The Chongqing Connectivity Initiative and its broader relevance to Singapore-China economic ties shall be elaborated in the subsequent sections.

8 Their joint venture, China Highway-Surbana Jurong Transportation Design and Research Co Ltd, is 51% owned by China Highway Engineering Consulting Corporation and 49% held by Surbana Jurong (Williams, 2017).

9 Most of the members of these associations are small- and medium-sized private firms. See BizQ (2019) and Surbana Jurong (2019a) on some of the avenues in which Surbana Jurong engages with the small- and medium-sized private firms.

10 As mentioned previously, small- and medium-sized private firms make up the bulk of the membership of these associations. See Business China (2018), Liu et al. (2016) for an elaboration on the roles of Business China and SCCI, respectively, in promoting Singapore-China ties.

11 The SBF is the city-state’s leading business chamber representing as many as 25,800 firms (mostly small- and medium-sized). It also represents smaller local and foreign business chambers.

12 Conducted by SBF, this annual survey collected views from over 1,000 (1,019) SBF members across all major industries from 11 October 2017 to 13 December 2017. All members were invited to participate via email and encouraged to complete the questions via phone reminders. For each firm, a maximum of one response was collected via an online survey platform. The survey covered a wide range of topics including manpower challenges, business transformation, and international expansion. Of the 1,019 firms polled, 84% were classified as small- and medium-sized private firms.

13 One of the most commonly cited natural disasters that impacted the Southeast Asian manufacturing industry is the 2011 Thailand floods which severely disrupted the operations of Japanese manufacturers based in the Kingdom. Since then, Japanese manufacturing firms are more aware of the need to better manage (or at least spread out the risk of) their supply chain in the region.

14 Dyson’s two principle supply chain partners are Meiban and Flex. Singaporean-owned Meiban started as a small firm supplying services to TNCs but has since expanded operations across China, Singapore, and Malaysia. Flex, founded in the US, has three sites in Singapore and a presence in a further 30 countries. Both firms work with Dyson in supplying parts for products like its famed vacuum cleaners and bladeless fans (see Ng, 2019).

15 One of the authors of this paper took part in a Collaboration Council meeting in 2017 and observed that the participants of both sides were those in charge of respective agencies involved in Singapore-China cooperation and the discussions were candid and productive, aiming at resolving specific issues and moving forward.

16 During one of the authors’ business trips to Qingdao in 2016 and 2017, the city’s leaders were very keen on attracting business schools from Singapore to set up a branch campus in Qingdao to further promote the establishment of the financial hub in the area of wealth management.

17 Teo Siong Seng is widely known as a proponent of the BRI and a supporter of stronger Singapore-China ties. He is also the Chairman of the SBF, which provides him with considerable clout in the domestic business community. See Teo, SS (2019) for his open call for Singaporean small- and medium-sized private firms to more aggressively tapping into commercial avenues opened up by the BRI.