Fast optical wavefront engineering for controlling light propagation in dynamic turbid media

Abstract

While propagating inside the strongly scattering biological tissue, photons lose their incident directions beyond one transport mean free path (TMFP, ∼1 millimeter (mm)), which makes it challenging to achieve optical focusing or clear imaging deep inside tissue. By manipulating many degrees of the incident optical wavefront, the latest optical wavefront engineering (WFE) technology compensates the wavefront distortions caused by the scattering media and thus is toward breaking this physical limit, bringing bright perspective to many applications deep inside tissue, e.g., high resolution functional/molecular imaging, optical excitation (optogenetics) and optical tweezers. However, inside the dynamic turbid media such as the biological tissue, the wavefront distortion is a fast and continuously changing process whose decorrelation rate is on timescales from milliseconds (ms) to microseconds (μs), or even faster. This requires that the WFE technology should be capable of beating this rapid process. In this review, we discuss the major challenges faced by the WFE technology due to the fast decorrelation of dynamic turbid media such as living tissue when achieving light focusing/imaging and summarize the research progress achieved to date to overcome these challenges.

1. Introduction

Light is a widespread and noninvasive tool with high spatial resolution which is useful for applications in the fields of in vivo medicine, biomedical imaging and treatments including various microscopy imaging, photodynamic operations, physiotherapy, etc. However, due to the intrinsic scattering property of the biological tissue, light usually loses its incident direction beyond one transport mean free path (TMFP). Therefore, existing methods for noninvasive high-resolution optical imaging or targeted therapy are usually limited within a depth of hundreds of micrometers (μm) or 1 millimeter (mm).

To overcome the above challenges, in many current biological imaging modalities such as confocal microscopy, two-photon microscopy and optical coherence tomography (OCT), special gating techniques are utilized to select limited scattered photons (ballistic photons and snake photons) for imaging.1,2,3 These strategies achieve fairly good spatial resolutions at a depth of hundreds of micrometers. With the increase in imaging depth, however, the number of acquired photons decreases exponentially. Therefore, revolutionary new thoughts are in urgent need for breaking the current limit of optical imaging depth in a real sense.

Through numerical simulations, previous studies have revealed the process of light propagation inside the scattering media and proved that scattering is a deterministic process. Further, substantial progress has been made on the diffuse optical imaging, e.g., imaging with spatial resolutions of several hundred μm was achieved at depths of several mm (laminar optical tomography), or imaging with spatial resolutions at mm or centimeter (cm) scales was achieved at depths of several cm (e.g., diffuse optical tomography, fluorescence molecular tomography and bioluminescence optical tomography).5,6,7,8,9 In these methods however, the physical resolution is relatively low, several orders of magnitude lower than the diffraction limited resolution. It is obvious that scattering has become a physical bottleneck which restrains in vivo optical applications deep inside tissue.

Fortunately, there is evidence showing that optical wavefront engineering (WFE) might be a useful tool for solving this problem. When biological scattering media have destroyed the wavefront of light propagation, optical WFE is able to detect and correct these distortions and might achieve high-quality optical imaging/focusing through or inside the scattering media. In 2007, Vellekoop and Mosk at the first time proposed the WFE technology.10 Based on the speckle interference phenomenon, by setting a goal of increasing the intensity of detected scattered light outside the media, they proposed a stepwise sequential algorithm (SSA, see Appendix A for details) to iteratively optimize the phases of the incident wavefront so as to maximally compensate the light wavefront distortions due to scattering and finally form high contrast optical foci through the scattering media. This study opened a new door for the development of WFE.

The development of WFE provides infinite feasibilities for optical applications deep inside living tissue. For in vivo functional/molecular imaging, high energy optical focusing is able to enhance the strength and contrast of detected signals and break through the physical limits of existing methods on sensitivity, resolution and depth of investigation. Other in vivo advanced technologies might include manipulating tiny targets like cells or proteins, activating certain nerve cells and related subregions, applying targeted therapy to disease areas, etc.

Since proposed, WFE has attracted much attention and developed very rapidly. A series of breakthroughs have been made in this field in aspects of theoretical basis, new techniques and experimental validation. Several review articles (those written by Mosk, Judkewitz, Horstmeyer, Kamali, Park, Kim et al.) have illustrated the important progress in WFE, including the theories of optical transmission inside scattering media,11,12,13,14,15,16 memory effects,17 feedback guided mechanisms,18,19,20 controlling approaches of optical waves,21,22,23 biological applications,24,25,26,27 etc.

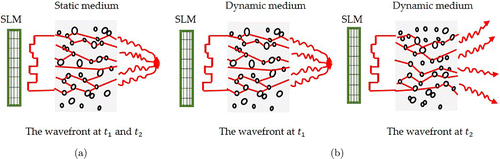

Different from the emphasis of the above review articles, this paper will specially review the research progress of WFE for overcoming the challenge of short decorrelation time in its applications on the dynamic turbid media, especially the living biological tissue. The nature of WFE is to detect and correct the wavefront distortions induced by the scattering media, based on the assumption that the scattering media are steady during light propagation, i.e., wavefront distortions induced by the scattering media are unchanging with time. As shown in Fig. 1(a), from time t1 to t2, the wavefront is steady and the peak-to-background ratio (PBR, see Appendix B for detail descriptions) is unchanging. Here, PBR is defined as the ratio between the peak intensity of the focus and the ensemble average of intensities of speckles, normally proportional to the ratio of the number of controllable optical modes (N) versus the number of optical modes inside the focus (M), N/M. In the living tissue, however, this assumption of steady media is difficult to be valid, since the motion inside tissue as well as physiological movements, e.g., respirations, heart beating and blood flow greatly change the optical scattering and propagating paths inside tissue. As shown in Fig. 1(b), from time t1 to t2, the wavefront changes and PBR keeps decreasing. If the speed of WFE is unable to beat such fast decorrelation, it is impossible to correct the distorted wavefront and manipulate the optical field, e.g., achieving optical focusing. To date, in-depth research work has been conducted to study the effect of tissue motion on optical focusing and different fast WFE solutions have been proposed to overcome this challenge.

Fig. 1. Wavefront through static and dynamic media at different times. (a) Wavefront at t1 and t2 through a static scattering medium and (b) Wavefront at t1 and t2 through a dynamic scattering medium.

Currently, there are several WFE approaches, and they are divided into analog and digital types by the criterion that the optical signal is acquired, stored and played back by analog or digital devices. In analog WFE approaches, wavefront modulation is realized using the holographic recording media (photorefractive crystal, photorefractive polymer, photochromic material, silver emulsion plate and so on) which record, store and play the optical wavefront in form of continuous signals. In digital WFE approaches, continuous optical signals are first transformed into electrical signals by photosensitive devices (CCD, CMOS), second transformed into digital signals through sampling, and then recorded, transferred and played. On the other hand, WFE approaches can be divided into different categories according to various implementing technical routes for the loop from the feedback signal to wavefront reconstruction. There are the optical phase conjugation (OPC), the feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization and the transmission matrix (TM) approaches.

This review is organized as follows. Section 2 mainly introduces the effect of scattering decorrelation on the WFE technology, Secs. 3–5 mainly introduce the principles and latest progress of analog optical phase conjugation (AOPC), digital optical phase conjugation (DOPC), feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization and TM approaches, respectively, Sec. 6 is the discussion and conclusion for the development, challenges and perspective of fast WFE.

2. Speckle Decorrelation

The speckle decorrelation time is defined as the time in which the speckle autocorrelation function and the turbidity suppression fidelity drop to a specific threshold (e.g., 1/e).28 For the static scattering media such as ground glass, the internal structure is stable, so theoretically the optical focusing based on the WFE technology is steady, unchanging with time. For the biological tissue, the internal cells and their substructures are in motion status, making the propagation paths of photons change on complicated interfaces, and hence the optical wavefront changes correspondingly. In detail, the decorrelation time of biological tissue depends on the type of tissue, region, depth and sample mobilization, usually on time scales from seconds (s) to milliseconds (ms), microseconds (μs), or even faster.28,29,30

2.1. The relation between speckle intensity autocorrelation function and WFE turbidity suppression fidelity

Based on the assumption that the scattering process is ergodic and the average transmittance is unchanging with time, the speckle intensity autocorrelation function, defined as the correlation between speckle patterns at time t0 and t0+Δt, is calculated from the sequential multi-speckle images captured by the camera as follows31 :

The WFE turbidity suppression fidelity is defined by29

The results of both theoretical and experimental studies show that the speckle intensity autocorrelation function is proportional to the WFE turbidity suppression fidelity :

2.2. The relation between decorrelation time and tissue depth

Brake et al. investigated the relation between decorrelation time and thickness of acute brain tissue slices from rats by using the diffusing wave spectroscopy (DWS) theory and the Monte Carlo photon transport simulation.30

In the experiment, it was measured that the mean speckle decorrelation time for rat brain tissue slices with thicknesses of 1, 1.5, 2 and 3mm was 9.38, 5.65, 3.95 and 2.27s, respectively. The decay rates of the decorrelation time curves increased with the increase of sample thickness. Since the TMFP of photons inside the ectocinerea of rat was ∼0.2mm, fitting the data of decorrelation time with those of tissue thickness (L), it was observed that their relationship shifted from a model of 1/L to 1/L2 when tissue thickness increased from 1 to 3mm. This phenomenon can be explained by the DWS theory which analyzes the dynamic nature of scatters by measuring the intensity correlations of speckle over time. That is, when the sample thickness is much greater than the TMFP, the light transmission can be regarded as diffusion, and it is predicted that the decay of the autocorrelation function is proportional to 1/L2; when the sample is thin enough (thickness equals to several TMFPs), the decay of autocorrelation function is proportional to 1/L. However, the experimental results did not fit the predictions of DWS theory perfectly. As a result, the photon propagation through tissue was simulated by the Monte Carlo simulation, and the results revealed several reasons. First, when the sample thickness was just several TMFPs, the photon transmission inside scattering media could not be regarded as pure diffusion. Due to that the scattering path lengths of quasi-ballistic photons changed linearly with the sample thickness, the practical scattering paths of photons tended to be shorter than those of diffusion, and thus the model of decorrelation time versus sample thickness shifted from 1/L2 to 1/L. Second, in thin tissue, the absorption effect of photons caused this relationship to move toward 1/L.

Qureshi et al. further investigated the relation between speckle decorrelation time and tissue thickness in the living mouse brain.28 A custom fiber probe which simulated a point-like source was minimally invasively inserted into the living brain of the anesthetic mouse, and the in vivo relationship between the speckle decorrelation time and tissue thickness was investigated by using the multi-speckle diffusion wave spectroscopy (MSDWS). The fiber probe was inserted from 1.1 to 3.2mm deep inside the brain, and a series of speckle images were acquired at each depth to analyze the decorrelation time. Results showed that the range of speckle decorrelation time in the living mouse brain was from several milliseconds at a depth of 1mm to several submilliseconds level when the depth was above 3mm (0.3ms at a depth of 3.2mm). With the increase of tissue thickness, since the photon scattering events increased, the speckle decorrelation time decayed approximately at an exponential rate. Compared with brain tissue slices, the blood flow in the living brain greatly decreases the decorrelation time. Therefore, the decorrelation time of living brain tissue is several orders of magnitude shorter than that of ex vivo brain tissue with the same thickness.

2.3. The relation between decorrelation time and motion

Related studies revealed that there were three types of perturbations affecting the speckle decorrelation: volumetric movements, microscale cell movements and Brownian motion in the fluidic environment.33 Blood flow is the major cause of fast decorrelation of biological tissues. Blood vessels distribute throughout the body in vivo, as networks among tissues and cells. The blood flow velocity varies with body locations. For example, for mouse the blood flow velocity is about 0.11mm/s in the capillaries and about 5.0mm/s in the arteries.34,35 It was found that the speckle decorrelation time ranged from 0.44ms (limited by the camera frame rate) to 10ms when measured from five different locations on the ear of the anesthetized mouse, and the time depended much on locations. Once the ear was clamped, the local blood flow was blocked, and the speckle decorrelation time greatly increased (>500ms).36

Actually, the effect of blood flow on decorrelation time in vivo can be reduced in specially designed experimental setting. For instance, different degrees of immobilization of living samples result in different decorrelation time. It was reported that the decorrelation time of mouse dorsal skin was about 2.5s if it was clamped by a force of ∼5 psi (blood pressure ∼2 psi) but about 50ms if it was unclamped. Besides, the imaging depth can also be increased if imaging regions less influenced by blood vessels were selected.29 For example, it was probed by fiber that the decorrelation time was 0.3ms at a depth of 3.2mm in a region without major blood vessels under the brain pial surface.28

In order to systematically demonstrate the decorrelation of various media in different situations, we summarize the typical data in related research work to provide a relatively direct understanding of the influence of depth, tissue, region and sample mobilization on the decorrelation time (see Table 1). Generally, a tendency is observed for the decorrelation time of tissue: the deeper the imaging depth, the more free the clamped state, the faster the tissue decorrelation. However, since the related research work is still at an initial stage and the experiments are done under different conditions in terms of tissue type, region and physical state, it is very difficult to make a direct comparison on the decorrelation of different media at different depths from the currently reported data in spite of these variations.

| Sample | Depth (mm) | Decorrelation time (ms) | Standard deviation (ms) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse brain | 1.1 | 7.5 | 5.9 | 28 |

| 1.8 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 28 | |

| 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 28 | |

| 3.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 28 | |

| Acute rat brain slices | 1 | 9380 | 3630 | 30 |

| 1.5 | 5560 | 1500 | 30 | |

| 2 | 3950 | 1030 | 30 | |

| 3 | 2270 | 890 | 30 | |

| Mouse dorsal skin flap (unclamped) | 1.5 | 50 | 29 | |

| Mouse dorsal skin flap (pinched with 5 psi pressure) | 1.5 | 2500 | 29 | |

| Mouse dorsal skin flap (natural free status) | 2.3 | 28 | 53 | |

| Mouse ear around capillaries | 7.21 | 36 | ||

| Mouse ear around arteries | 0.159 | 36 | ||

| Mouse ear (block the blood flow) | >500 | 36 | ||

| Rabbit ear | 1500 | 33 | ||

| Static sample | >180000 | 36,49 |

3. AOPC

In 1966, the study conducted by Leith and Upatnieks et al. showed that the phase conjugated wavefront could be used to compensate the light phase distortion inside the thin scattering media.37 In 2008, Yaqoob et al. utilized the photorefractive 45∘-cut 0.075% Fe-doped Lithium Niobate crystal (LiNbO3) as the holographic recording medium and proposed a turbidity suppression by OPC technology.38 The phase reconstructed image was obtained through a 0.69mm thick chicken breast tissue slice and the reconstructed focus peak intensity was enhanced by ∼5×103 times. There were two working steps in this OPC system: recording and playback. In the recording step, the reference beam interfered with the scattered sample beam, and the interference images were recorded by the holographic recording media. Then, the phase information of the scattered sample beam was calculated through homography and read out by a reference beam which was then played back through the scattering medium from the back side to the front side. The wavefront distortion was compensated in the playback process and the phase recovered images were generated at the location of the original light source. The AOPC systems developed very rapidly. Using AOPC, Cui et al. subsequently successfully focused the light through rabbit ear (decorrelation time was about 1.5s).33

The above AOPC systems were demonstrated on the biological tissue in a transmission or reflection mode. However, it is much more desirable for applications inside the biological tissue, e.g., delivering optical energy to targeted positions or obtaining clear images in vivo. In order to successfully generate optical foci or images inside living tissue, Xu et al. referred the concept of guidestar which originates from the astronomy field and proposed a novel technology by combining the focused ultrasonic modulation with OPC, called time-reversed ultrasonically encoded (TRUE) optical focusing.39 In this TRUE system, the phase conjugate mirror was the photorefractive Bi12SiO20 crystal (BSO) and the optical focus was built at the location of ultrasonic focus inside tissue.

In the validation experiment of TRUE, the imaging sample was a 10mm thick scattering slab mixed from porcine gelatine, distilled water and 0.25% Intralipid. In this physical phantom, it was the first time that noninvasive and scannable optical imaging was successfully achieved deep inside the highly scattering media.

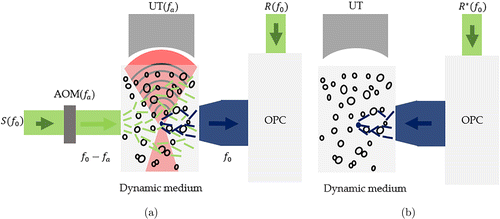

The mechanism of TRUE is explained in detail below. Figure 2 shows the light modulation by ultrasonic waves. The coherent beam is split into three parts: the sample beam S(f0), the reference beam R(f0) for holographic recording and the conjugate reference beam R∗(f0) for the hologram read-out, where f0 is the frequency. Then S(f0) passes through the acousto-optic modulator (AOM(fa)) which turns S(f0) to S(fs) (where fs=f0−fa) before it transmits through the scattering sample. A focused ultrasonic transducer at a frequency of fa generates ultrasonic waves which form an ultrasonic focus area inside the sample and modulate the scattering photons inside it. The modulated scattering photons (whose frequency is shifted ±fa by the ultrasonic waves and turned to be f+=f0 or f−=f0−2fa) can be regarded to be emitted from a virtual optical source (the ultrasonic focus) and then exit the sample. This virtual optical source is called guidestar. In the scattered sample beam, only ultrasonic encoded photons at the frequency of f0 interfere with the reference beam R(f0), and the interference hologram is then recorded by the BSO crystal. Similar to OPC, the conjugate reference beam reads out the hologram and generates the time-reversed wavefront for the ultrasonic encoded light. When played back, the time-reversed wavefront focuses at the location of the ultrasonic focus inside the scattering sample. Since it is feasible to move the ultrasonic focus area (location of the guidestar) inside the scatter if it is controlled by a scanning device, the TRUE system actually achieved nonnvasive and scannable imaging inside a tissue-mimicking phantom.

Fig. 2. Principle of TRUE. (a) Recording step. The sample beam S(f0) is first turned to a frequency of f0−fa by AOM (fa) before entering the scattering medium, and S(f0−fa) is modulated by the ultrasonic wave (fa) and changed to be S(f0) or S(f0−2fa). These modulated photons are regarded to be emitted from a virtual optical source (the ultrasonic focus) namely guidestar and exit from the scattering medium. Only ultrasound encoded scattered light S(f0) interferes with the reference beam R(f0) to realize the phase conjugate recording process. (b) Playback step. The phase conjugated wavefront is time-reversed to achieve light focusing at the ultrasonic focus.

The emergence of TRUE technology opened the door for optical excitation and imaging applications inside the strongly scattering biological tissue, and attracted much attention. More research work was conducted and promoted the performance indices of TRUE technology, e.g., depth and resolution of focusing. Addition to the transmission-mode TRUE introduced above, the reflection-mode TRUE has also been developed.40,41,42

However, in the reports of AOPC above, the response time of crystals such as BSO and LiNbO3 was usually from several hundred ms to several s, unable to beat the in vivo speckle decorrelation time which is at ms level.

In order to promote the OPC response speed, Liu et al. in 2015 utilized a 1% tellurium-doped tin thiohypodiphosphate photorefractive crystal (Te-doped Sn2P2S6) with a faster response speed as the holographic recording medium in their TRUE system and decreased the time-reversal latency to 5.6ms.36 Owe to this short time delay, the system successfully focused the light at a wavelength of 793 nanometers (nm) through a living-mouse ear with a decorrelation time of 5.6ms.

The response speed of Liu’s system can be further promoted. The response time of Te-doped Sn2P2S6 is closely related to the illumination intensity.43 For instance, the response time of Te-doped Sn2P2S6 decreases from 7 to 1.3ms when the illumination intensity increases from 1 to 10W/cm2. Consequently, increasing the intensity of the reference beam can further decrease the crystal response time, as long as under the damage threshold of the photorefractive crystal. However, this action breaks the optimal ratio between the intensities of reference and sample beams and will decrease the PBR, which needs to be properly balanced.

Currently, the system latency of AOPC is able to reach milliseconds level. Meanwhile, AOPC has other advantages, e.g., a large photosensitive area and a large number of pixels and is able to complete more integrated phase conjugation. The number of controllable optical modes for AOPC is as high as 1011. As a result, a higher PBR will be obtained with the same focus size.44,45 This is extremely important for imaging inside tissue. Taking TRUE for an example, at the existing technical level, if using the focus of high-frequency ultrasound as guidestar, since the size of optical mode deep inside tissue is a half of the optical wavelength, there are tens of thousands of optical modes inside a focusing circle with a diameter of 30–50 μm. Therefore, AOPC is still able to form optical foci with high PBR deep in vivo.

However, there is no energy amplification in AOPC systems. Here, we use optical gain to quantify the amount of energy transfer and the optical gain is defined as the optical energy of phase conjugated light compared with that of original incident light. Even special techniques have been adopted to increase the optical gain,46 the optical gain of AOPC is still much less than 1. Although Suzuki et al. have successfully demonstrated fluorescence imaging on a specially designed scattering phantom using AOPC,47 AOPC is very difficult to meet the high energy requirement in practical applications such as functional/molecular imaging, optical excitation and light control.

4. DOPC

DOPC is the digital version of OPC. Different from AOPC, the recording and playback steps in DOPC are carried out by separate digital devices. Recording is conducted by a digital photosensitive device such as a camera which records the interference information between the sample and reference beams. Playback is implemented by a spatial light modulator (SLM) which is completely conjugate with the photosensitive device. Compared with AOPC, the greatest advantages of DOPC are that it can transfer more optical energy and is more adaptive to different wavelengths. However, DOPC systems are more complicated, where the recording and playback devices must be completely conjugate.

In 2010, Cui et al. at the first time proposed the DOPC technique and successfully focused the light through a scattering medium — a mixture of polystyrene microspheres with different diameters.48 The number of controllable optical modes was as high as 106 and the PBR of the reconstructed optical focus was about 600. In this digital system, a composition of a CCD camera with a SLM replaced the role of the photorefractive crystal in AOPC. The CCD camera was used to record the interference wavefront between the scattered sample beam and the reference beam. An electro-optics (EO) modulator changed the relative phase shifts between two coherent beams and four interference images were recorded. Through the four-step phase-shifting method, the optical information of the scattered sample beam (amplitude and phase) were calculated in the computer which further digitally phase conjugated the measured waveform and transferred it to the SLM for playback.

Subsequently, important progress has been made on the DOPC research work in aspects of achieving optical focusing or imaging through or inside the scattering media.29,49,50,51,52 However, the latencies of these DOPC systems based on SLM and digital camera are usually 200ms or even longer. The main reasons are as follows. First, the refresh rate of liquid crystal SLM is slow, at a level of tens of milliseconds. Second, limited by the camera response rate and low-speed of the four-step phase-shifting method (which needs to acquire four camera images), the recording procedure is relatively time consuming. Third, the data computing and transfer procedures based on traditional computers including image reading, processing and displaying result in a longer latency.

To overcome the challenges above, Wang et al. in 2015 realized a fast DOPC system with a latency of only 5.3ms, two orders of magnitude faster than those previously reported.53 Controlling 1.3×105 optical degrees of freedom (1920×1080 pixels, each speckle occupied 12 pixels), the proposed system accomplished sustainable optical focusing through a living mouse dorsal skin with blood flowing through it (decorrelation time about 30ms) and the PBR reached about 180.

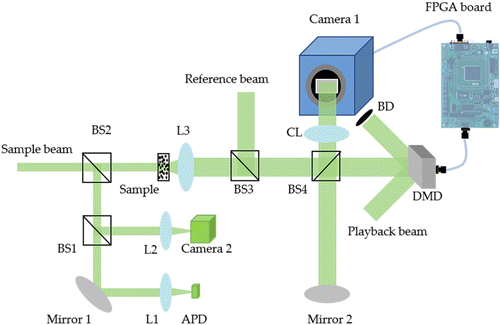

The DOPC system of Wang et al. was based on the digital micromirror device (DMD) and its simplified schematic is shown in Fig. 3. The system was speeded up by three key strategies. First, a DMD based on the microelectromechanical system (MEMS) technology was adopted as the modulating device, whose refresh rate could be as high as 23kHz, two orders of magnitude faster than that of the traditional liquid crystal SLM (LC–SLM). Second, the field programmable gate array (FPGA) was introduced into the system to speed up the data processing. FPGA has the high-speed parallel computing ability and processes data transfer and procession with low latencies. Further, data procession latency could be practically eliminated by overlapping the data procession with image transfer from the camera by parallel assembly line. Finally, since DMD only provided binary modulation,54 a single-shot binary phase retrieval technique was proposed, which required only single camera image to calculate the phase of binary optical field fit for DMD meanwhile simple for calculation and suitable for FPGA implementation. It is also worth noting that since DMD is only capable of binary phase modulation, under the same number of controllable optical modes, the PBR of DMD-based systems only reserves 20% of its value in SLM-based systems which are capable of performing gray level phase modulation.

Fig. 3. A simplified schematic of the DMD-based DOPC. The scattered sample beam interferes with the reference beam and interference images are captured by Camera 1. The DMD and Camera 1 are aligned pixel-to-pixel and they are connected through a host FPGA. (L is lens; BS is beam splitter; BD is beam dump; CL is camera lens; APD is avalanche photodiode).

The monolithic fast OPC device was proposed with advantages of on-chip/onboard high-speed data transfer, no need for complicated alignment task between recording and playback devices, etc. In 2013, Laforest et al. combined VLSI integration with a standard liquid crystals on silicon (LCOS) process and designed a fast on-chip OPC device which integrated the functions of image acquisition, computing and playing back.55 The latency of this system only depends on the response time of liquid crystal. With future progress of this work, the DOPC system with a much faster speed might be realized.

Similar to the principle of analog TRUE, Wang et al. in 2012 introduced the ultrasonic guidestar into their DOPC system and successfully accomplished digital TRUE with a high optical gain (about 5×105).49 This digital TRUE system achieved optical focusing as well as fluorescence imaging at an acoustic resolution of ∼30μm in between two 2.5mm thick ex vivo chicken tissue slices. Independently, Si et al. proposed a similar TRUE approach at the same time.56 Compared with analog TRUE, the advantages and disadvantages of digital TRUE both rely on the core technology of DOPC, much higher optical gain but much less controllable optical modes. Note that in the related prototype validation work of digital TRUE, little attention was paid on the speed of the system, and the latency for once optical focusing is tens of s.

In 2017, Liu et al. proposed a digital TRUE system with a latency of only 6ms, whose speed was one to two orders of magnitude higher than those reported in previous literatures.57 The major speed-up strategies were as follows. First, in traditional digital TRUE systems, light field was obtained by adopting the four-step phase-shifting method where four holograms were collected. Here, a novel method was proposed which calculated the binary optical field information (phase was near 0 or π) and only required to collect two holograms, decreasing 50% of the optical field recording time. Two frames were collected when the focused ultrasound was applied, and the phase of the focused ultrasound shifted by π from the collection time of the first frame to that of the second frame. Through this action, the binary optical field information could be obtained by simply comparing the optical intensities of two frames. Second, a ferroelectric LC–SLM with a low latency (a net latency including data transfer and liquid crystal response time was only ∼1ms) was adopted and it worked well with the binary optical field information provided. Third, the latencies of data collection and transfer were reduced through software optimization.

In the recording step of digital TRUE, most bits of the camera were used to record the informationless background but not optical signals carrying the phase information of the sample beam. As a result, cameras with high dynamic ranges (e.g. 16-bits) needed to be utilized and there was heavy load for data transfer.49,56,58,59,60 Besides, the shot noise inside raw signal with high background portion sharply reduced the SNR of collected light field. To addressing these challenges, Liu et al. in 2016 proposed a novel lock-in camera-based digital TRUE system.61 Different from traditional digital TRUE systems, the original high-frequency (fa) ultrasound modulation was added by a low-frequency component (fb=70kHz). Through the lock-in signal detection inside the lock-in camera, the optical field information of sample beam could be directly obtained under single exposure of the camera. Meanwhile, before the optical field information arrived at analog-to-digital converter, the background portion had been removed by the lock-in step. Therefore, this system had lower need for high sampling bits and sharply reduced the data transfer load. It was reported by the authors that the acquisition time of the optical field was decreased to 0.3ms. Although in this principle demonstration, the authors did not optimize the data transfer and playback steps, it is expected in the future the latency of such digital TRUE system can be reduced to less than 1ms if the system was combined with DMD or high-speed ferroelectric amplitude modulating SLM.

For guidestar-assisted focusing inside the scattering media, there were other studies using the moving target guidestar to rapidly acquire the guidestar wavefront. In 2014, Zhou et al. and Ma et al. respectively, proposed their novel OPC techniques using dynamic disturbance as guidestar.51,52 For example, if a moving particle is regarded as the guidestar and it moves from one location to another location inside a static scattering medium at two different moments, the difference between scattered sample beams acquired at these two moments will only result from the disturbance induced by the moving particle. Making differences on two optical fields and playing back the phase conjugated wavefront, high contrast optical focus can be formed back to the location of the particle. Nevertheless, in these methods, it needed to measure the optical field twice and take subtraction. If the four-step phase-shifting holography technique was utilized, two optical field measurements acquired 8 images, which greatly reduced the system speed. To overcome this challenge, Ma et al. in 2015 proposed a single-exposure binarized time-reversed adapted perturbation optical focusing method to acquire the phases, namely bTRAP.62 In this method, within the single exposure time of the camera, the pulsed laser ejected two consecutive incident shots onto the sample, and the phase of reference beam which interfered with the scattered laser shots changed by π from the illumination periods of the first to the second shot, and two interference holograms were recorded in the camera. Then, a binary light field could be calculated from two holograms which recorded two interference patterns occurring within the single camera-exposure time. The significant benefit of this method is that the light field recording time does not depend on the camera frame rate but the laser repetitive rate. For a pulsed laser with a repetitive rate higher than 1MHz, one measurement of the optical field is less than 1μs. Consequently, the ultimate latency of bTRAP method relies only on the image transfer and SLM refresh rates.

Although different in implementation details, DOPC systems introduced above normally include a SLM and a recording camera. The fastest DOPC system to date based on this setting, however, can only achieve a system latency at milliseconds level. Acousto-optics (AO), however is much faster than SLMs or DMDs since it is able to control the wavefront amplitude and phase, modulate the frequency, and steer beams as well. Based on AO, Feldkhun et al. in 2019 introduced a phase control technique using programmable acoustic optic deflectors (AODs) which was theoretically able to achieve light focusing within a latency at μs scale.63 In this method, an array of beams encoded by RF signal (phase modulated) were ejected from AODs, and transmitted through the scattering medium, and a fast single-pixel detector at the same time captured the phases of the scattered beams. The above whole process lasted just 10μs. Next, the beams were phase conjugated by AODs to generate a spatio-temporal focus. This method was called the Doppler Encoded Episodic Phase Conjugation (DEEPC). In DEEPC, phases of N spatial modes were modulated simultaneously with N distinct frequencies Ωn provided by AODs before illuminating the sample, and the scattered beam interfered with the reference wavefront at the targeted focus place through or inside the scatter and the interference was detected. Then Fourier-transform was performed on the detected signal to recover the local phase of each mode which was then conjugated and inputted into AODs as the feedback signal. As a result, the modes interfered constructively to form a focus. In this demonstration, the wavefront measurement on 100 individual optical modes took just 10μs.

Since data acquisition was conducted by the digital oscilloscope and FFT was performed by the computer, this study only demonstrated fast wavefront measurement. However, if FPGA was utilized for high-speed signal acquisition and procession, the time of playback procedure can also be controlled within 10μs. Note that the AO method is not limited either by the low fresh rate of SLM or by the low frame rate of the camera, but depending on the Doppler encoding and RF-electronic control of AO diffracted beams, and wide-bandwidth single-pixel detection as well. Additionally, the current number of controllable optical modes is just several hundred.

To summarize, the energy gain of DOPC systems is high, and their speeds have also reached ms or even μs level, approaching the speed requirement of practical in vivo applications. However, compared with AOPC, the number of controllable optical modes of DOPC is relatively small (less than 106). With the current level of guidestar techniques, it is still challenging for DOPC to build high contrast optical focusing deep inside the biological tissue.

5. Feedback-Based Iterative Wavefront Optimization and Transmission Matrix Measurement

Different from OPC which requires only single measurement, the iterative wavefront optimization and TM measurement approaches achieve the optical focusing/imaging through multiple measurements, and their principles as well as demonstrations are introduced as follows.

The light scattering and propagating characteristics inside media can be represented by the transmission matrix T. Given the incident wavefront Ein composed of N incident optical modes, the output wavefront Eout after optical delivering by the scattering media can be calculated from Eout=TEin.

In order to enhance the target light intensity (single or multiple targets), since T is unknown, the feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization approaches calculate and modify the incident mode of next moment by Ein and Eout of current moment, and the target light intensity eventually reaches maximum after continuously iterating and searching.

Different from the iterative wavefront optimization approaches, the TM measurement approaches calculate T directly. In detail, through projecting a series of incident wavefront Ein (whose phase patterns are known) on the scattering media, the corresponding output wavefront Eout is detected, and T can be directly solved through the equation: T=EoutE−1in.

5.1. Feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization approaches

In 2007, Vellekoop and Mosk proposed a feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization approach and achieved a light focus (with a brightness that was 1000 times higher than that of the normal diffuse transmission) through a scattering medium composed of TiO2 pigment with a thickness of 10.1μm.10 This was the first time that the feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization was utilized to achieve the energy enhancement of the optical target by optimizing the optical transmission inside strongly scattering media. As mentioned before, they divided SLM into 3228 individual segments, and independently changed the phase distribution (0–2π) of each segment. As a result, the incident wavefront was adjusted and then a CCD camera acquired the target intensity inside the scattered optical field. By altering the phase distribution of SLM while simultaneously detecting the target intensity, this method iteratively optimized the results until the target intensity reached maximum.

In practical applications, it is normally not feasible to place physical detectors at target locations inside the medium. In related studies, researchers attempted to utilize the fluorescent microspheres as target guidestar, and to enhance the energy at these locations by optimizing and enhancing the outside detected fluorescent signal intensity.64,65,66 However, the fluorescent microsphere guidestar is more used for theory and feasibility validations than in practical applications due to that it is embedded into the media, neither scannable nor moveable. Similar to the guidestars used in the OPC technology (those based on optic-acoustic interactions), the optoacoustic effect is rapidly introduced into the iterative waveform optimization as a type of noninvasive and scannable guidestar.

Optoacoustic guidestar is based on the optoacoustic effect. When the scattering medium is illuminated by the light emitted from a pulsed laser or a modulator, light absorption increases its internal temperature. This makes some internal structures and volumes change periodically and begin to radiate ultrasonic waves outward. In the study of Kong et al., the incident beam illuminated the scattering media (composed of paraffin and graphite particles) and focused on a light absorptive target inside the media.67 Then through iteratively enhancing the detected optoacoustic signals outside the media and playing back the phase conjugated wavefront, optical focusing can be generated inside the scatter at the location of ultrasonic focus. In this study, the repetitive rate of pulsed laser was low, and the time delay for a single optimization was relatively long, making it take 20minutes (min) to complete the iterative optimization over 140 pixels.

Based on the acousto-optical effect, similar to TRUE, Tay et al. proposed an acousto-optical guidestar applicable for feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization.68 The scattering light (at an incident frequency of f) inside the media which was included in the ultrasonic focus area was modulated by the high-frequency ultrasound (whose frequency was Δf), and changed to be at a frequency of (f+Δf), and a new optical source (f+Δf) was generated at the location of the ultrasonic focus. Outside the media, the ultrasound-encoded light at a frequency of (f+Δf) and with an intensity of I was detected by the photoelectric detector and optical focusing was accomplished at the location of ultrasonic focus inside the media through enhancing I by iterative optimization. Although it has been validated that the optoacoustic and acousto-optical guidestars were capable of forming optical foci inside scattering media, the demonstrations were time consuming, on time scales of tens of minutes. Therefore, it is very necessary to promote the speeds of these systems if they are attempted to be applied on the dynamic turbid scattering media.

The speed of feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization mainly relies on factors including the number of controllable optical modes (N), the times for wavefront refreshment, data acquisition, data transfer and computing during each iteration as well as the convergence of the iterative algorithm. Limited by factors such as low-speed liquid crystal SLM and the speed of PC used for data acquisition and procession, the speeds of currently reported iterative wavefront optimization systems are all relatively low, i.e., the iteration time is usually above several hundred milliseconds when the number of controllable optical modes is from several hundred to several thousand.

In 2017, Blochet et al. demonstrated a fast iterative wavefront optimization system.69 This system adopted a MEMS–SLM (KiloDM segmented, Boston Micromachines) as high as 10kHz to implement fast wavefront playing, and utilized FPGA to implement high-speed signal acquisition and used continuous sequence algorithm (CSA, see Appendix A for details) for iteration. This system reached a processing speed of 243μs/mode and achieved optical focusing with PBR≈10 through a scattering sample with a decorrelation time of about 30ms.

An all-optical feedback-based WFE method is very interesting. The reported system utilized a multimode laser cavity inside which an optical field self-organized itself, and optical foci were formed ex vivo through 200μm thick chicken breast tissue slices at a speed of submicrosecond time scale by manipulating around 1000 controllable modes.70 Compared with conventional WFE where a SLM was used to modulate the spatial phase pattern, this method all-optically achieved the optical focusing (pinhole target) through iterations under the condition that the relative phases and frequencies of the independent lasing modes were locked. In spite of its extremely fast speed, this technique made use of the optical feedback from the desired position, preventing it from achieving optical focusing inside the biological tissue by using a guidestar.

5.2. Transmission matrix measurement approaches

In 2010, Popoff et al. at the first time generated a single light focus with a PBR of 54 through an 80 μm thick strongly scattering medium composed of ZnO sediment.71 In this study, SLM was divided into 256 segments. The input signal was a series of wavefront consisting of the Hadamard bases, and the four-step phase-shifting method was utilized to measure the output wavefront. The acquisition time for the whole TM approach was 3min, relatively time consuming. Later, by using the photoacoustic guidestar based on the photoacoustic effect, Chaigne et al. reported the optical enhancement inside the ultrasonic focus using a TM measurement approach, verifying the feasibility of noninvasive and scannable WFE based on TM measurement.72

Similar to the feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization, TM measurement also requires multiple measurements. For N controllable optical modes, it normally needs to project 3N sequences to obtain T. Therefore, factors including the number of controllable optical modes (N), times of wavefront refreshing and data acquisition for each iteration as well as times of data transfer and computing determine the speed of TM measurement.

In 2013, Conkey et al. successfully promoted the speed of TM measurement by adopting DMD and FPGA simultaneously.73 The system controlled 256 optical modes with a latency of about 37ms and the single mode time was about 145μs/mode, and this speed was promoted by at least three orders of magnitude compared with the LC–SLM based methods.

The system promoted its speed by the following three strategies. First, high-speed phase modulation was carried out by a DMD encoded off-axis binary-amplitude computer-generated holography, and the adoption of DMDs brings advantages, e.g., the high efficiency of phase modes and high frame rate. In most current methods, LC–SLM is used for phase-only wavefront modulation,10,71,74,75,76,77 which can more efficiently create the optical focus than the amplitude-only modulation.54 Besides, under the same number of input modes, the theoretical enhancement based on the phase-only wavefront modulation is five times higher than that of the binary amplitude modulation.10,54 However, the switching speed of LC–SLMs is limited by the aligning rate of liquid crystals in the device, typically 10–100Hz, 1–2 orders of magnitude slower than the kHz rate required by the biological tissue whose decorrelation time is at milliseconds scale. On the other hand, commercially available DMDs show a maximum full-image frame rate as high as 22.7kHz. To overcome this challenge, Conkey et al. proposed an off-axis binary amplitude holography to realize the phase-only modulation using DMDs. As a result, they simultaneously took advantages of the high efficiency of phase modes and high frame rate of DMDs. Second, 256 input modes predefined by the system were preloaded on DMD, ensuring DMD to refresh at the maximum full-image frame rate of 22.7kHz. The displaying and switching times for each hologram on DMD were both 22μs, and the total time per image was 44μs.78 Finally, FPGA instead of computer was utilized for high-speed computing and data transfer, reducing the calculation time to just 3ms, two orders of magnitude shorter than before.

Subsequently, the multimode fiber (MMF) was introduced into this system and the whole system achieved real-time focusing through dynamically bending the MMF, further validating the feasibility of using MMF as the super micro aperture endoscope.79,80 In most biomedical applications, it needs to insert MMF into the tissue, however, perturbations such as bending the MMF cause the spatial configuration of optical modes change, and a phase controlling ability of 22kHz is capable of correcting the perturbations induced by bending the MMF.

Although phase modulation implemented by a DMD using a hologram can simultaneously achieve higher enhancement and higher speed, it results in phase resolution loss, and the light efficiency is usually very low (10%). The light efficiency of direct intensity modulation (i.e., amplitude-only modulation) can reach 60%.78,79 Higher diffraction efficiency provides higher SNR at target positions and thus increases the accuracy of TM measurement. Tao et al. adopted the direct intensity modulation in their study, and in order to avoid the low SNR induced by the low intensity of reference field, they proposed a reference optimization method which scanned the speckles on the target. The higher diffraction efficiency of this method would result in higher SNR during the interference acquisition for the multi-photon fluorescence imaging.81

As shown above, using DMD to modulate the phase can speed up the TM measurement approaches by 1–2 orders of magnitude, this speed however is still low for biological tissue which dynamically changes on a time scale of milliseconds. In 2018, by adopting the 1D grating light valve (GLV) with a refresh rate as high as 350kHz as the phase playing device, Tzang et al. promoted the speed of their TM measurement system by four orders of magnitude compared to those based on LC–SLM.82 For 256 input modes, the total time length of 768 measurements used for confirming TM was 2.15ms. Adding the times for data transfer and computing, the total latency of this TM-based WFE was 2.4ms, i.e., average mode time was 9.4μs.

In previous studies, spatial light modulation was implemented by two-dimensional (2D) devices, e.g., SLM and DMD, this study however adopted a fast one-dimensional (1D) SLM (i.e., GLV) to realize 2D WFE making use of the scattering media to complete the 1D–2D transformation. GLV (F1088-P-HS) was composed of 1088 pixels each consisting of 6 ribbons. By electronically controlling the deflection of ribbons, GLV worked as a programmable 1D phase modulator. With faster switching time (<300ns), allowing operations with a high repetition rate (350kHz) and continuous phase modulation, GLV is 3–4 orders of magnitude faster than LC–SLM, one order of magnitude faster than the binary amplitude DMD and other binary phase modulators. The system used a group of predefined phase masks which were preloaded into the GLV memorizer to maximally shorten the data transfer time between GLV and computer, allowing GLV to display all preloaded images at the maximum frame rate. Additionally, the wide-bandwidth data transfer hardware, a dual-port data acquisition scheme and multi-threaded C++ application programs were adopted to speed up the data transfer. However, due to the limitations of current manufacture technologies, the measurement accuracy of GLV was not high. Besides, the limited phase range of GLV decreased the accuracy of the calculated wavefront.

To summarize, with the introduction of FPGA and various fast wavefront modulating devices and designs, currently fast TM methods are able to reach response speeds at milliseconds level, and important progress has been made for overcoming the shortcomings, e.g., dynamic perturbations induced by MMF. However, the number of controllable optical modes are small (hundreds to thousands modes) in the TM measurement approaches, so it is very challenging to apply TM in very deep (more than several millimeters) in vivo applications. But at a depth of 1–2mm or more, the TM method is promising to play a very important role, e.g., promoting the detection depth limit of OCT by one or more times.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Since proposed, significant progress has been made on the development of optical WFE, which opened the door for high-resolution imaging and energy delivery deep inside strongly scattering media, and made breakthroughs on application-oriented explorations in fields of optogenetics,36,53,78,83,84,85 high-resolution microscopy imaging,86,87,88 endoscopic imaging,79,89,90,91,92,93 etc. According to different technical implementation routes, optical WFE approaches are divided into four main categories including AOPC, DOPC, iterative wavefront optimization and TM measurement. These technical routes have individual advantages and disadvantages, and may develop in parallel or cross-merging with each other in the future. For practical applications on the dynamic turbid scattering media especially the living tissue, WFE technologies must beat milliseconds level or even shorter decorrelation time of the media, and this makes the system speed become one of the bottleneck challenges in this field.

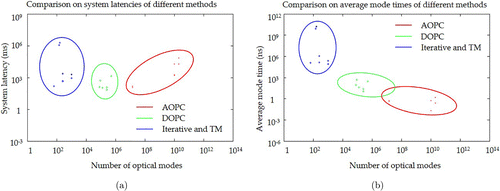

Figure 4 below summarizes and compared the speeds of the state of art most advanced WFE systems based on different technical routes in aspects of the number of controllable optical modes, system latency and average mode time. It is shown that for WFE, the larger number of the controllable optical modes, the more complete phase conjugation that can be performed, the higher PBR that can be achieved under the same focus area,45 which is essential for imaging deep inside biological tissue. As shown below, in terms of number of controllable optical modes, AOPC is the highest, from 1010 to 1011, DOPC ranks second, usually from 105 to 107 and the feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization and TM are the lowest, from 102 to 103. In terms of the system total latency, all technical routes of WFE have pushed the speeds of their fastest systems to milliseconds level, meeting some needs of the in vivo applications. However, it is worth noting that in terms of the average mode time, the performances of different technical routes based WFE vary by several orders of magnitude. For AOPC and DOPC, the average mode times are at picosecond (ps) and ns scales, respectively. For iterative wavefront optimization and TM, the average mode times are at μs scale.

Fig. 4. Comparison on the speeds of various state-of-the-art WFE methods. (a) is system latency versus number of optical modes and (b) is average mode time versus number of optical modes. In (a) and (b), circles, diamonds and crosses represent various technical implementations of the AOPC,33,36,38,39,40,41,45,47,94 DOPC,49,53,57,61,62 and feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization and TM measurement,67,69,72,73,78,79,80,81,95 respectively, and their ranges are represented by red, green and blue ellipses.

As described in detail in the sections above, all technical routes of the WFE technology have proposed new theories, designs and engineering schemes for promoting the system speed. Although differing greatly with each other, these strategies have several important considerations in common. First, for reducing the time of wavefront recording step, AOPC adopts faster photorefractive crystal; DOPC proposes the entirely new single camera exposure technique to calculate the binary or full optical field; and iterative wavefront optimization and TM measurement utilize SLMs with higher refresh rates to decrease the data collection time in each iteration. Second, it is to reduce the data transfer and computing times, mainly for digital WFE. To achieve this goal, most systems adopt the FPGA with a high parallel computing ability and a low latency. Meanwhile, in some applications, instead of overcoming the difficulties in FPGA programming and implementation, strategies like using high-performance workstations and software optimization also perform well in time-saving. Besides, we should also pay attention to some novel and useful ideas. For example, introducing the lock-in camera sharply reduces the data transfer amount in digital TRUE systems. Third, it is to reduce the response time of spatial optical modulation. For AOPC, this also relies on the optimization of photorefractive crystal, and for DOPC, feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization and TM measurement, they depend on the design of specialized system schemes as well as the selection of faster SLMs.

It is worth noting that although different WFE approaches have all reached a processing-time level of milliseconds and have already completed initial in vivo validations, the tissue decorrelation time is increasing exponentially with depth and closely related to the distribution of vessel networks. For example, for the anesthetic living brain, the decorrelation time can reach 0.3ms at a depth of 3.2mm. Therefore, it is necessary to push the speed to μs scale for applications deep inside the living tissue. Here, the development of semiconductor technologies such as high-speed cameras, high-speed SLMs and board-level data transfer and procession (e.g., FPGA) will boost the speed promotion. Moreover, innovative and new thoughts are more than necessary to be introduced to this field if the speed performance is expected to be promoted revolutionarily by several orders of magnitude. Fortunately, so far some promising novel ideas have been proposed and light is being shed on the future studies. Although restricted by the demonstration scenarios or have not been demonstrated in vivo, the all-optical feedback and AOD-based OPC technologies have theoretically validated the feasibility of pushing the system speed to ps or μs scales. Meanwhile, since AOPC technology is implemented all-optically and benefits from its large number of controllable optical modes, if new thoughts are proposed which can greatly promote the optical energy enhancement in AOPC and meanwhile the speed can be improved by strategies like introducing special-designed optical crystals, AOPC might be a promising solution for beating the fast decorrelation of living biological tissue.

SNR will become one of the greatest challenges in the development and applications of ultrafast WFE. In order to ensure enough SNR, previous literatures usually selected relatively high optical budgets in the prototype demonstrations and validations. Under the nearly noise-free condition, the achievable PBR is proportional to the number of controllable optical modes (N). For ultrafast WFE technologies however, the allowable exposure time is quite short, and hence the number of detectable photons (proportional to the exposure time) will greatly decrease. Especially for applications deep inside the scattering media, the number of detectable photons further decreases, making the SNR near or even lower than 1. Typical noises include ground noise of the detection device, shot noise of the optical signal, and so on. For ground noise of the detection device, taking the camera pco.edge (utilized in many existing DOPC systems) for an example, the read-out noise for each pixel is about 1.5 e−(rms, optical quantum efficiency ∼50%). Shot noise of the optical signal results from the uneven ejection of electrons, and the standard deviation of shot noise is equal to the square root of the ensemble averaged intensity of measured photoelectrons on the target position. When there is only shot noise, SNR is proportional to the standard deviation of the light intensity.

Researchers have investigated and analyzed the effect of noise on PBR. For the feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization, Yilmaz et al. investigated the effect of different types of noises on PBR.96 For the typical SSA iterative algorithm model, Yilmaz et al. deduced and built the analytic relationship between PBR and noise and proposed a pre-iteration strategy aiming at reducing the camera readout noise. In this pre-iteration strategy, the selected number of operative modes N0 at the initial optimization was much lower than the eventual number N. The fundamental idea of this strategy was to maximize the change of optical intensity in each segment adjustment during iterations so as to escape from the camera readout noise regime as fast as possible. This explains why the partition algorithm (PA, see Appendix A for details) is more robust to noise, since it adjusts a half of the total controllable elements in every iteration. Next, Yilmaz et al. further founded that in the shot noise limited regime (where the camera readout noise is neglectable), the PBR achievable by the iterative wavefront optimization was proportional to the number of averaged photoelectrons detected per optimized segment. Interestingly, Jang et al. drew a similar conclusion on OPC under low photon budget conditions.97 The study of Jang et al. demonstrated that under low photon budget conditions, even though the number of detected photons per degree of freedom was as low as 0.004, as long as that the resolution of OPC was high enough (the number of controllable optical modes N was high), OPC was still able to be successfully applied, and PBR was proportional to the total number of detectable photons by all camera pixels. Surprisingly, under the condition of extremely low photon budget, the camera readout noise was much higher than the detectable signals, this however did not affect PBR, different from the result under the same condition for the feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization approaches. The reason is probably that there is no iterations in OPC, and the influence caused by the random readout noise in a large number of measured modes is counteracted and averaged.

As mentioned above, under the condition of limited exposure time, increasing the photon budget and reducing the effect of detection noise are two effective ways to be considered to ensure the PBR performance of ultrafast WFE. The photon budget depends on the energy of input beam (limited by the security threshold of biological tissue) and the tagging efficiency of guidestar. Currently, the tagging efficiency of guidestar is relatively low, e.g., the tagging efficiencies of typical ultrasound guidestars are less than 1%.98 Therefore, in the future it needs to optimize or introduce new guidestar techniques.99,100 In terms of the detection noise, strategies like selecting low-noise detectors and designing algorithms robust to noise should be paid attention.

Fast WFE is currently theoretically demonstrated mainly in the transmission-mode systems (where OPC and the light source locate, respectively, at two sides of the scattering sample). For the biological tissue, the reflection-mode system (where OPC and light source locate at the same side of the scattering sample) is of more practical value in many scenarios. However, it is relatively simple to apply the ideas and techniques of current transmission-mode fast WFE to reflective-mode systems.40,41,42,59,101,102,103,104,105 It is expected that in the near future, more applications of reflective-mode systems on the dynamic and turbid scattering media will be conducted and reported.

To conclude, with the development of fast WFE, it is promising in the near future to see the realization of high-resolution imaging, optical excitation and optical manipulation deep inside the dynamic turbid scattering media, providing revolutionary technical tools for the fields including neuroimaging, oncotherapy, optogenetics, etc. and pushing forward new developments of in vivo molecular imaging, regulation, diagnosis and treatment.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 61675013, 61101008 and 31771071), the National Key Research and Development Plan (2018YFC2001700).

Appendix A

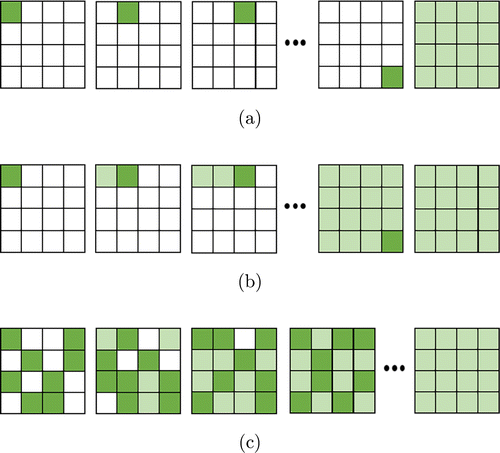

Figure A.1(a) shows the main idea of SSA algorithm. The phase of each segment changes from 0 to 2π to find its optimal value which corresponds to the maximum feedback light intensity and this optimal phase is stored. The above action traverses throughout all segments in the modulator, and finally, the optimal phase data are entirely loaded into the modulator to construct the optimal wavefront. In the absence of measurement noise and time instability, SSA can find the global maximum with minimum times of iterations.10

Fig. A.1. Principles of feedback-based iterative wavefront optimization algorithms SSA, CSA and PA. (a) Principle of SSA, which sequentially optimizes and records the phase of each segment, and finally updates the optimized phases of all segments on the spatial light modulator. (b) Principle of CSA, which is the same as SSA except for that the modulator refreshed immediately after the phase of each segment is optimized. (c) Principle of PA, which randomly selects and optimizes the phases of a half of all segments and updates the spatial light modulator in each iteration. Light green indicates segments to be optimized, and dark green indicates segments which have been optimized.

Two other classic algorithms, CSA and PA, respectively, are demonstrated in Figs. A.1(b) and A.1(c).

Similar to SSA, CSA also requires traversing all the segments. The major difference between these two methods is that the phase of each segment is directly refreshed by its optimal value after each iteration in the CSA algorithm. As a result, even if the dynamic characteristics of the sample change, CSA is able to track accordingly.

For PA, it is not necessary to obtain prior information about the stability of sample. The idea of PA is as follows: in each iteration, all segments are randomly divided into two groups (each group containing half segments) and the phases of segments in one group are simultaneously changed. As a result, the intensity of detected signal increases rapidly, especially after initial iteration. Besides, this algorithm is expected to be more robust to noise and can be quickly recovered from disturbances.75

Appendix B

PBR is a quantitative index of the focus contrast. The higher the PBR, the better the focus contrast. Besides, it has been proved that PBR is proportional to N/M, where M and N are the numbers of optical modes in the focus and the number of controllable modes on the SLM, respectively. So theoretically a larger N divided by a smaller M will consequently increase PBR. One way to increase N is to adopt SLMs with more controllable optical modes and PBR will be increased under the same experimental conditions. A smaller M might be achieved by using a smaller size guidestar. Caution should be taken if the guidestar with a very small size is adopted. For instance, in the TRUE system shown in Fig. 2, if the ultrasonic guidestar is very small in size, the area of ultrasonic modulation inside the scatter will be sharply reduced, which will greatly decrease the number of modulated scattered photons, weaken the signal intensity of the time-reversed wavefront and decrease the SNR. This will reduce the PBR. In addition, in order to more accurately evaluate the system performance and meanwhile set a criterion for suitable comparisons among different systems, a system efficiency index was proposed and defined as the ratio of the system implemented PBR to the theoretical PBR. In practical implementations, PBR is usually calculated by the ratio between the focus average intensity and the ensemble average of the intensities of speckles when a random wavefront is applied.