Seeing through dynamics scattering media: Suppressing diffused reflection based on decorrelation time difference

Abstract

We observed a phenomenon that different scattering components have different decorrelation time. Based on decorrelation time difference, we proposed a method to image an object hidden behind a turbid medium in a reflection mode. In order to suppress the big disturbance caused by reflection and back scattering, two frames of speckles are recorded in sequence, and their difference is used for image reconstruction. Our method is immune to both medium motions and object movements.

1. Introduction

Optical imaging is an important way to see the world. However, multiple-scattering, which a photon undergoes in turbid media, such as biological tissue, polluted water, fog and haze, scrambles the wave front and disables all conventional optical imaging method. This is because the point-to-point relationship between the object and the image planes is destroyed by the multiple scattering whereas, the information carried by the wave front, even being scrambled, is still there, and can be extracted by proper methods.

Of late, the common methods to extract information from scattered light includes wave-front shaping,1,2,3 optical phase conjugation,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 transmission matrix measurement,12,13 and memory effect-based scattering point spread function (PSF) deconvolution14,15,16 and speckle autocorrelation.17,18,19 Among which, speckle autocorrelation attracts more and more attention because of its simple system, fast response and noninvasive feature. Currently, all reported speckle autocorrelation imaging focuses on a transmission mode to the best of our knowledge. But in practice, a reflection mode is more suitable for subcutaneous diagnosis, underwater scan and so on. A main problem in the reflection mode is that the intensity of the sum of the diffused reflection and backscattering light (hard to differentiate each other), which we call disturbance hereafter, is always much larger than the signal. Because of the irregular shape and internal heterogeneity, e.g., a variation of number density of scattering particles, of the turbid medium, the disturbance has spatial fluctuations, resulting in a severe dilution of the signal. As far as we know, all published work of reflection mode avoids the problem by either spectral filtering,18 i.e., illuminating the medium and the embedded fluorophore object with a short wavelength light and detecting the excited long wavelength fluorescence, or physical shielding,20 i.e., blocking the disturbance with some blackboards.

In this paper, based on the decorrelation time difference between the disturbance and the signal, we proposed a method to filter out the disturbance to extract an image. In the following content, the principle and experiment setup are introduced in Sec. 2, Sec. 3 is the experiment and simulation result, finally a summary is given in Sec. 4.

2. Principle and Experimental Setup

We know that particles in a turbid medium always have Brownian motion, so the temporal autocorrelation of diffused light field through the medium can be written as21

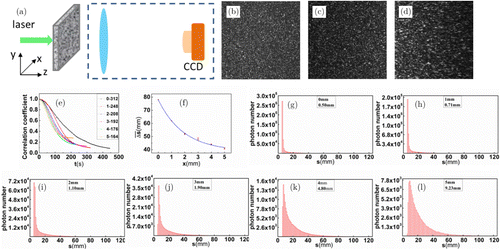

As increases, the speckles become larger but with an attenuated contrast as shown in Figs. 1(b)–1(d), which results in a gradually risen tail in autocorrelation curve in Fig. 1(e). The decorrelation time is defined as the time when the autocorrelation coefficient reduced from the peak to its half of the bell-shape autocorrelation curve. Figure 1(f) is the decorrelation time versus . The value of the decorrelation time can vary from seconds to minutes depending on the sample storage time in a refrigerator, room temperature and duration time of experiment. But the trend of the curve preserves. The longest decorrelation time is at . A possible explanation is that the path length difference near the optical axis is the smallest. In order to verify this, we implemented a Monte Carlo simulation by launching photons to a turbid layer with the same thickness and as the tissue-mimicking gelatin sample. A mm2 square area, corresponding to the interested photosensitive area of the CCD camera, is selected on the output plane. Figures 1(g)–1(l) show the path length histogram of photons reaching the square area when its center is placed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5mm along axis, respectively. The width of the histogram grows with , implying an increased path length difference , consequently a bigger fluctuation of phase variation24 resulting in faster speckle decorrelation.

Fig. 1. The relationship between decorrelation time and different scattering components. (a) Experiment setup, the back surface of the gelatin layer is imaged onto the CCD with a magnification factor of 5. (b)–(d) are corresponding speckle patterns achieved at 0, 3 and 5mm, respectively. (e) The temporal autocorrelation curves at different locations, the inserted legend is presented in a manner of “line type-location -decorrelation time”. (f) The relationship between decorrelation time and location . (g)–(l) path length histograms at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5mm, respectively, where in each inserted legend, the location and the corresponding FWHM are presented.

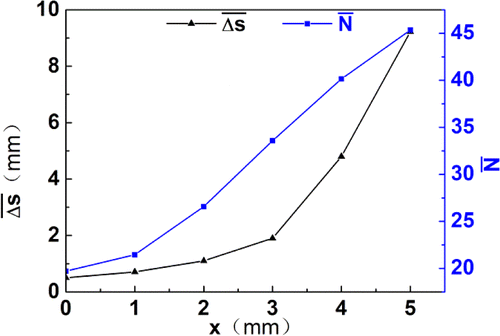

For the same scattering medium, a larger path length means more scattering events happened in the path. So, it’s quite straight to link the decorrelation time with the number of scattering. Figure 2 shows a comparison of an average path length difference and an average number of scatterings, they are correlated. Thus, it’s safe to say that the bigger the number of scattering is, the less the decorrelation time will be.

Fig. 2. A comparison of an average path length difference and an average number of scattering versus location .

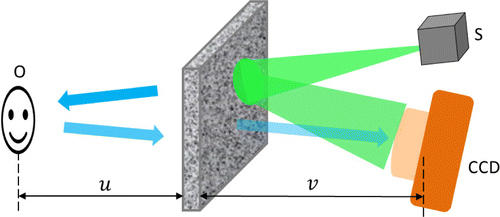

Now, it’s natural to take advantage of the decorrelation time difference to suppress the disturbance in the reflection mode. We know that in disturbance, diffusion reflection and single scattered light has dominant weight. Usually, it decorrelates slower than the transmitted light, especially for thick media. So, the disturbance can be eliminated by subtraction of two successive speckle patterns. Figure 3 shows the schematic experiment setup.

Fig. 3. A schematic of experiment setup. cm and cm are distances from the object and the CCD camera to the medium, respectively. The cerulean lines denote the light transmitted through the scattering medium. Its wavelength is the same as the green ones.

An incoherent light source, i.e., a pseudo thermal source generated by a laser illuminated on a rotating ground glass disk, illuminates a scattering layer, both reflected light from a target and the disturbance from the layer surface are detected by a CCD camera (Stinggray F-504B) on the same side with the source. Within the memory effect range, the intensity distribution on CCD can be written as

For two patterns recorded at time and , under the condition of , where is the decorrelation time of the PSF, is the decorrelation time of the disturbance. The difference of the two patterns is

Two kinds of media are selected for experimental demonstration, one is a movable ground glass disk plus a stationary homemade raw glass plate with the plate facing the source, the other is a tissue-mimicking gelatin gel sample made by porcine gelatin, distilled water and 20% intralipid with a thickness mm and a scattering coefficient mm.

3. Results

3.1. Ground glass sample

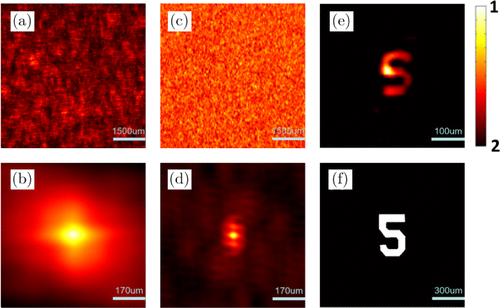

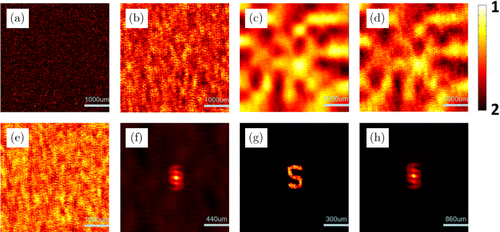

For the glass sample, the decorrelation time of the disturbance is larger enough to be considered as infinite. We first record a speckle pattern, then rotate the ground glass disk a quarter turn and record another pattern. An example of the recorded speckle pattern is shown in Fig. 4(a). Since the reflected disturbance is so big that the information of the hidden object is submerged, no image can be reconstructed from Fig. 4(a) based on Gerchberg–Saxton algorithm. In contrast, an image with clear characteristics shown in Fig. 4(e) is reconstructed from .

Fig. 4. Experiment result of the ground glass sample. (a) is a captured speckle pattern, signal light is submerged in disturbance, not image can be acquired based on the single pattern. (b) the autocorrelation of (a). (c) The difference of two frames and (d) the corresponding autocorrelation. (e) The reconstructed image with a magnification . (f) A photograph of the target.

3.2. Simulation

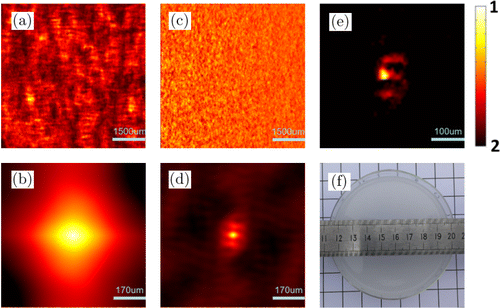

In order to have an intuitive understanding of our method, we did a simulation. First a transmission mode is considered without any disturbance and noise. The experimental parameters are applied in the simulation. A spatial random light field is reflected by the object, then transmits through a random phase mask acting as the scattering layer and reaches the recording plane. A coherent speckle pattern (e.g., Fig. 5(a)) is obtained. By sampling different s and summing the coherent speckle patterns, we get an incoherent speckle pattern (see Fig. 5(b)). An image can be extracted from the autocorrelation of Fig. 5(b). If we add a random noise on Fig. 5(b), when the noise amplitude reaches half the fluctuation amplitude of Fig. 5(b), no image can be reconstructed based on the same algorithm. If we add a DC background to Fig. 5(b), the image is extractable no matter how big the DC background is theoretically. However, large DC background can saturate the camera and make the signal indistinguishable in practice. Finally, if we add a disturbance to Fig. 5(b), once its fluctuation amplitude is large enough, the original characteristics of Fig. 5(b) is overwhelmed.

Fig. 5. Simulation result for an intuitive illustration of our method. (a) is a coherent speckle pattern, (b) is an incoherent speckle pattern by summing 2000 coherent ones, (c) and (d) are the same disturbance added to two different incoherent speckle patterns, respectively. (e) is a difference of (c) and (d). (f) the autocorrelation of (e). (g) the reconstructed image. (h) is the autocorrelation of the number “5” itself.

Although, no image can be reconstructed from the autocorrelation of either Figs. 5(c) or 5(d), the autocorrelation of their difference agrees well with the autocorrelation of the object itself (see Figs. 5(f) and 5(h)). Two identical disturbances for two subsequent speckle patterns means there is no decorrelation in the disturbance. However, in most practical cases, the disturbance fluctuates and the difference of two slightly changed disturbance patterns introduces noise which will result in a failure of the method once its amplitude is large enough.

3.3. Tissue-mimicking gelatin gel sample

For the tissue mimicking sample, the decorrelation of the disturbance causes big noise in difference to submerge the signal. In order to increase the signal intensity, we introduce a light beam from the source to directly illuminate the object. Since the decorrelation time is time varying, it’s hard to know its exact value while recording speckles. Thus, we record a sequence of speckle patterns with 2s intervals. Two patterns separated by 30s are selected to reconstruct the image. The result is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Experiment result of the tissue-mimicking gelatin layer. (a) is a captured speckle pattern, no image can be acquired from it. (b) is the autocorrelation of (a). (c) The difference of two frames and (d) the corresponding autocorrelation. (e) is the reconstructed image. (f) is a photograph of the tissue-mimicking gelatin sample.

Similar to the ground glass disk, the image of the object can be reconstructed from with a deteriorated image quality due to the decorrelation of the disturbance.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Previously, movements of turbid media, no matter the internal Brownian motion, turbulence and flow, or the external ones, are always thought to be harmful for imaging, especially for methods like wave-front shaping, optical phase conjugation and transmission matrix measurement.9,26,27,28,29,30 Massive research powers focus on increasing the speed to complete detection within decorrelation time. We first proposed the method to take advantage of the dynamic characteristics. In above, we only studied the stationary object. In fact, our method is immune to motions of both scattering media and the target. When the target is moving, so long as it is smaller than the memory effect range, Eq. (4) holds. We can still extract its image no matter what a big distance it travels. Since the disturbance varies with time in most practical situations, once the residue of the difference is large enough depending on reconstruction algorithms, the method will not work.

Instead of integrating autocorrelation over all path lengths, we observed the phenomenon that different scattering components have different spatial distribution and their decorrelation time is different. We also found an empirical relationship between the decorrelation time and the number of scatterings. Based on an assumption of the decorrelation time difference between the PSF and the disturbance, we proposed and demonstrated an autocorrelation imaging method that can work in the reflection mode without the assistance of fluorescence or physical shielding. Our method is very applicable in dynamic environment and has great potential in underwater detection, seeing through fog, tissue imaging, etc.