Spatial sensitivity to absorption changes for various near-infrared spectroscopy methods: A compendium review

Abstract

This compendium review focuses on the spatial distribution of sensitivity to localized absorption changes in optically diffuse media, particularly for measurements relevant to near-infrared spectroscopy. The three temporal domains, continuous wave, frequency domain, and time domain, each obtain different optical data types whose changes may be related to effective homogeneous changes in the absorption coefficient. Sensitivity is the relationship between a localized perturbation and the recovered effective homogeneous absorption change. Therefore, spatial sensitivity maps representing the perturbation location can be generated for the numerous optical data types in the three temporal domains. The review first presents a history of the past 30 years of work investigating this sensitivity in optically diffuse media. These works are experimental and theoretical, presenting one-, two-, and three-dimensional sensitivity maps for different Near-Infrared Spectroscopy methods, domains, and data types. Following this history, we present a compendium of sensitivity maps organized by temporal domain and then data type. This compendium provides a valuable tool to compare the spatial sensitivity of various measurement methods and parameters in one document. Methods for one to generate these maps are provided in Appendix A, including the code. This historical review and comprehensive sensitivity map compendium provides a single source researchers may use to visualize, investigate, compare, and generate sensitivity to localized absorption change maps.

1. Introduction

Over the previous 30 years, researchers have studied the spatial distribution of photon energy associated with light that enters a diffuse medium at one location and exits at another.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,a These studies are often intended to assess the 𝒮 of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) techniques in biomedical diffuse optics; however, the results are still applicable to any methods that make measurements in a diffuse medium.

𝒮 may be interpreted by the idea of photon visitation probabilityb when continuous wave (CW) I is considered, however, the idea of 𝒮 can be extended beyond this for other data types.43 These other data types may include, for example, the ϕ in frequency domain (FD) or the σ2 in time domain (TD).44,45 For these cases, there are methods to obtain a Δμa (i.e., Δμa,𝒴), from a change in the data type (i.e., Δ𝒴).41 Furthermore, 𝒴 need not be some data type recovered from a single pair of sources and detectors (i.e., single distance (SD)) but instead from a spatially resolved (i.e., over ρs) measurement of optical data. These methods have been variously referred to as Spatially Resolved Spectroscopy (SRS),46,47 single slope (SS),35 or dual-slope (DS).35,c Regardless of the choice of measurement method, in the case of small-μa perturbations, the measured Δ𝒴 is related to the recovered Δμa,𝒴 through some proportionality factor, often referred to as Differential Path-length Factors (DPFs)49 or Differential Slope Factors (DSFs).38

The true Δμas can be spatially localized (i.e., Δμa,pert(r)) or homogeneous (i.e., Δμa,pert,homo). In the homogeneous case, the recovered Δμa,𝒴 is equal to the true perturbation Δμa,pert,homo.d However, in the case of a spatially localized perturbation, Δμa,𝒴 is almost never equal to Δμa,pert(r). Instead, Δμa,𝒴 represents the homogeneous change that would be consistent with the measured Δ𝒴. Therefore, we sometimes name Δμa,𝒴 the recovered effective homogeneous change. The sensitivity, 𝒮, relates the recovered absorption change measured by data type 𝒴 (Δμa,𝒴) to the true local absorption perturbation in absorption at position r (Δμa,pert(r)). Therefore, the 𝒮 for a particular data type (i.e., 𝒴) is a function of the spatial location (i.e., r) of the localized perturbation (i.e., 𝒮𝒴(r)). The exact definition of 𝒮 and why it can be interpreted in this way are further explained in Sec. 3.1.

This review aims to gather results from a variety of previous works, both experimental and theoretical, to provide a reference source for readers interested specifically in spatial maps of 𝒮. Importantly, we also remake and present two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) spatial maps 𝒮 for various NIRS methods and data types. This is to provide the reader with a single source for 𝒮 maps pertaining to most NIRS methods, including the MATLAB code utilized to generate the maps (found in Appendix A) so that one may recreate or modify them.50 In doing so, we present the majority of these 𝒮 maps on the same color scale so that they may all be compared.

To achieve this, we give a brief historical review of the works investigating 𝒮 and discuss the various methods and data types studied (Sec. 2). Then, in Sec. 3, we formally define 𝒮 (Sec. 3.1) and explain the methods used to generate the 𝒮 maps (Appendix A.1) in this compendium. The maps themselves are presented as both 2D cross-sections and 3D iso-surface volumes in Sec. 3.2. CW, FD, and TD are covered in Secs. 3.2.1–3.2.3, respectively. Each subsection explores data types specific to that temporal domain and includes measurements both at a single ρ, i.e., SD, or across multiple ρs, i.e., SS or DS (see footnote c).35

1.1. Nomenclature

1.1.1. Measurement methods

The NIRS methods considered in our review can be classified in various ways. The first is the temporal domain of the measurement method: TD,45 FD,44 or CW.51 The next is the optode arrangement which can be either: SD, a measurement between a single source and a detector spaced by a ρ; SS, a measurement of optical data as a function of ρ by using multiple sources or multiple detectors32,52; or DS, which also measures the optical data dependence on ρ but from a symmetric set of sources and detectors meeting specific geometric requirements.36,48

Lastly, we can categorize each temporal domain further, considering the measurements possible in each. In CW, there is only one data type, I.51 For FD, there is amplitude, referred to as FD Ie and ϕ.44 TD becomes more complex as various kinds of data can be extracted from the Temporal Point Spread Function of detected photons (TPSF).37,45 In this review, we focus on the 〈t〉f and σ2.g In addition to these, we may also consider TD I from different t gated portions of TPSF.h All of these data types exhibit different spatial 𝒮 which we show in Sec. 3.2.

1.1.2. Modeling methods

Various methods have been used to obtain 𝒮 maps or the ones similarly interpreted to 𝒮. Two less common methods are Lattice Random Walk (LRW)12,53,54 and modeling of Photon Paths (PPs),55,56,57 which are briefly mentioned in Sec. 2. Many more commonly used methods rely on Diffusion Theory (DT), which may be formulated in various ways.58,59 DT solutions may be arrived at numerically or analytically. One possible numerical method is the Finite Element Method (FEM) allowing for complex volumes of scattering media.60,61 Analytical solutions for DT typically must consider more simple media (e.g., infinite or semi-infinite); a majority of the maps presented in Sec. 3.2 entail this method which is explained in Appendix A.2. Finally, photon propagation may be simulated directly with equally common Monte Carlo (MC) methods.62,63 Using MC, one may calculate the times relative to when a photon was launched such that each photon spends in each voxel of a simple or complex medium allowing direct calculation of 𝒮.i Aside from direct calculation, adjoint methods for MC have also been developed providing a more computationally efficient estimation of 𝒮; some maps in Sec. 3.2 utilize adjoint MC which is explained in Appendix A.3.19,25

2. History of Previous Works on Sensitivity

Table 1 shows the select works that studied the spatial distribution of something similar to 𝒮 in chronological order. Many of these works may not present 𝒮 according to the specific definition in Sec. 3.1 for our maps in Sec. 3.2, but all the works present some results that can be interpreted in a similar way. This chronological list helps show how the work has progressed over the last 30 years.

| Relevant figures in citation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citation | Temporal domain | Primary method | 1D | 2D | 3D |

| Weiss et al.1 (1989) | CW | LRW | 2 | ||

| Barbour et al.2 (1990) | CW | MC | 2 | ||

| Schweiger et al.3 (1992) | TD | FEM | 5 | ||

| Schotland et al.4 (1993) | TD | DT | 4 & 7 | ||

| Sevick et al.5 (1994) | FD | Exp. | 5, 6, & 8 | ||

| Mitic et al.6 (1994) | TD | Exp. | 8–13 & 15 | ||

| Patterson et al.7 (1995) | TD | Exp. | 6 | ||

| Feng et al.8 (1995) | CW | DT | 5 | 2–4 | |

| Arridge9 (1995) | TD | DT | 7–10 | 5 & 6 | |

| Okada et al.10 (1995) | CW | MC | 4–7 | ||

| Boas et al.11 (1997) | FD | DT | 3 & 5 | ||

| Weiss et al.12 (1998) | TD | LRW | 5 | ||

| Dehghani and Delpy13 (2000) | CW | FEM | 4–9 | 3 & 10 | |

| Cox and Durian14 (2001) | CW | DT | 6 | ||

| Lyubimov et al.15 (2002) | CW | PP | 2 | ||

| Liebert et al.16 (2004) | TD | MC | 2–5 | ||

| Bevilacqua et al.17 (2004) | FD | MC | 2, 3, 8, & 9 | 1 & 7 | |

| Torricelli et al.18 (2005) | TD | DT | 2 | 1 | |

| Hayakawa et al.19 (2007) | CW | MC | 5.1 | ||

| Eames et al.20 (2007) | CW | FEM | 1 | ||

| Pifferi et al.21 (2008) | TD | Exp. | 2 | ||

| Haeussinger et al.22 (2011) | CW | MC | 9 | 1 | |

| Sawosz et al.23 (2012) | TD | Exp. | 2–6 | ||

| Mazurenka et al.24 (2012) | TD | Exp. | 3 & 4 | ||

| Gardner et al.25 (2014) | CW | MC | 4–8 | ||

| Gunadi et al.26 (2014) | TD | Exp. | 4 & 6 | 3 & 5 | |

| Brigadoi and Cooper27 (2015) | CW | MC | 4 | ||

| Wu et al.28 (2015) | CW | FEM | 1 | ||

| Martelli et al.29 (2016) | TD | DT | 2–5 | ||

| Milej et al.30 (2016) | TD | MC | 2 & 3 | ||

| Binzoni et al.31 (2017) | FD | DT | 1–6 | ||

| Niwayama32 (2018) | CW | MC | 2 | ||

| Yao et al.33 (2018) | TD | MC | 2 & 3 | ||

| Sawosz and Liebert34 (2019) | TD | DT | 2–5 & 7–9 | ||

| Sassaroli et al.35 (2019) | FD | DT | 2, 6, 8, 10, & 11 | 5, 7, 9, 12, 16, & 17 | |

| Fantini et al.36 (2019) | FD | DT | 1–13 | ||

| Wabnitz et al.37 (2020) | TD | DT | 5, 9, & 10 | 2–4 & 8 | |

| Blaney et al.38 (2020) | FD | DT | 3 & 4 | ||

| Perkins et al.39 (2021) | FD | FEM | 3 | ||

| Fan et al.40 (2021) | FD | FEM | 2 | ||

| Sassaroli et al.41 (2023) | FD | DT | 3–8 & 10–14 | ||

| Fazliazar et al.42 (2023) | TD | Exp. | 7 & 8 | 3–6 | |

Five columns summarize the works cited in Table 1. The first column identifies the most advanced (i.e., greatest possible information content and access to the most advanced and greatest quantity of data types and analysis methods) temporal domain that the work considers (i.e., CW, FD, or TD).j The second column indicates the primary method used to study 𝒮 (i.e., LRW, MC, analytical DT, Experimental (Exp.), FEM, or PP). Finally, the last three columns indicate the pertinent figure numbers within the referenced works which present 𝒮-like results. These three columns are split into one-dimensional (1D) scans, 2D maps, and 3D volumes.

2.1. 1980s

The first work we chose to review is that of Weiss et al.1 (1989) which used the LRW method to present the probability density function for photon visitation as a function of depth for photons measured by an SD in CW. The LRW method of solving photon migration in tissue has its own distinct solutions, however, it has been shown53,64 that one can carry out asymptotic limits to the random walk equations (i.e., for lattice spacing approaching zero and rate at which steps are made to approach infinity) and obtain either the diffusion equation (i.e., for uncorrelated random walks) or the telegrapher’s equation (i.e., for correlated random walks). Therefore, it is expected, at least in those situations where the diffusion conditions are fulfilled, that a solution obtained with the uncorrelated random walk will yield substantially the same solution as analytical DT. We also remind that both diffusion equation and telegrapher’s equation (i.e., P1 approximation65) are derived from the more general radiative transfer equation (i.e., under some approximations for the radiance), which is usually solved by the MC methods.

2.2. 1990s

Moving into the 1990s, we find many works which are beginning to use different methods and create 2D or 3D volumes of 𝒮-like quantities. First, a 2D map of something similar to 𝒮 was found in Ref. 2 (1990) which used MC simulations. Then Schweiger et al.3 (1992) showed the change in TD data types from a localized perturbation in a cylindrical medium; this is an early publication using FEM with a comparison to MC. Schotland et al.4 (1993) used eigenfunction analytical expansions of DT to arrive at the 2D maps of photon hitting densities for a homogeneous box, and the numerical solutions to result in similar maps but for a heterogeneous medium. Next, Sevick et al.5 (1994) and Mitic et al.6 (1994) showed FD and TD results from experiments on phantoms, respectively. Finally, to wrap up a concentration of experimental works, Patterson et al.7 (1995) conducted similar experiments in TD but instead focusing on penetration depth.

Feng et al.8 (1995) in their seminal work coined the term banana for the shape of the 𝒮 region for an SD arrangement in CW; this paper may be considered the first which really allowed good visualization of these banana 𝒮 regions and included 3D volumes. This work was closely followed by Ref. 9 (1995) which showed a plethora of analytical solutions to DT with a focus on tomographic reconstruction. Next, Okada et al.10 (1995) explored the 𝒮 regions on a geometry meant to match a head by incorporating the consideration of two heterogeneous layers. Boas et al.11 (1997) made some practical considerations by analyzing these ideas in terms of Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) which is important to determine feasibility. Finally, wrapping up the 1990s is the work of Weiss et al.12 (1998) with one of the later LRW papers, this time applied to TD.

2.3. 2000s

In the 2000s, we first have Dehghani and Delpy13 (2000) who investigated how the optical properties in a more realistic head model affect 𝒮 regions using an FEM solution to DT. Next, Cox and Durian14 (2001) carried out a more detailed investigation of the DT solutions with a comparison to MC. Lyubimov et al.15 (2002) studied photon visitation distributions in a less common way by considering the average Photon Paths within a diffuse medium. Liebert et al.16 (2004) focused on TD and a multiple ρ approach (i.e., SS) in an attempt to separate deep versus superficial perturbations. In the same year, Bevilacqua et al.17 (2004) utilized MC to investigate scaling relations on variables that affect the penetration depth associated with FD data including the conditions of short ρ or high μa for which DT may not be applicable.

In the second half of the 2000s, Torricelli et al.18 (2005) proposed a TD method which utilized a ρ of 0mm (i.e., null distance) showing its corresponding 𝒮 region. To tackle the computation time taken to calculate 𝒮 maps with MC, Hayakawa et al.19 (2007) developed an adjoint method. As the field developed, more emphasis was put on generating 𝒮 for image reconstruction; for example, Eames et al.20 (2007) investigated an efficient reduction (i.e., removing imaging regions which do not significantly affect the result) of the 𝒮 (i.e., Jacobian). Wrapping up the 2000s, we highlight Pifferi et al.21 (2008) who continued work to make TD feasible at small ρ and showed an experimentally generated 𝒮 map.

2.4. 2010s

Continuing to the 2010s, we find Haeussinger et al.22 (2011) who studied how the 𝒮 region changes on a subject-specific basis by using realistic models. Sawosz et al.23 (2012) were able to utilize a time gated camera for TD detection to experimentally create maps of photon visitation. Continuing the vein of interesting instrumentation and experimental work, Mazurenka et al.24 (2012) investigated the depth probed by a proposed noncontact TD method. Then, Gardner et al.25 (2014) extended the earlier work on adjoint MC and generated 𝒮 for 3D tissue models. Also, in the same year Gunadi et al.26 (2014) explored the spatial 𝒮 of three different NIRS instruments experimentally.

Moving to the second half of the 2010s, we review the work of Brigadoi and Cooper27 (2015) which investigated the 𝒮 of short ρs for subtraction methods. As the field continued to move to image reconstruction methods, Wu et al.28 (2015) proposed a fast and efficient image reconstruction on the human brain by leveraging the FEM. Martelli et al.29 (2016) conducted a more theoretical investigation of photon penetration by deriving expressions for the statistics of photon depth. In the same year, a technology development paper was published by Milej et al.30 (2016), who proposed a subtraction-based TD approach and investigated its 𝒮 depth. The following year, Binzoni et al.31 (2017) published another theoretical paper that reported analytical expressions for 𝒮 with totally absorbing defects. Niwayama32 (2018) investigated the SS approach and the type of 𝒮 distributions it achieves. Meanwhile, in the same year, a different MC method was presented by Yao et al.33 (2018) for investigating perturbations using an approach to re-simulate specific Photon Paths. Finally, wrapping up the 2010s was the proposal of the DS method for TD by Sawosz and Liebert34 (2019) and for FD by Sassaroli et al.35 (2019) with Fantini et al.36 (2019) showing many 𝒮 maps for different implementations of the method.

2.5. 2020s

The most recent decade, the 2020s, continued the new trend of using various data types with Wabnitz et al.37 (2020) investigating the 𝒮 of various methods in TD. Then, Blaney et al.38 (2020) continued the work on DS and presented the calculation of its 𝒮 and SNR. The next year, Perkins et al.39 (2021) expanded the work on imaging by leveraging the 𝒮 of different FD data types. Fan et al.40 (2021) also conducted investigations of the 𝒮 of FD data, this time with emphasis on the impact of fmod. Following this, Sassaroli et al.41 (2023) showed various new FD data types that achieve features, such as 𝒮, similar to those associated with higher-order TD moments. Finally, the most recent paper we review is by Fazliazar et al.42 (2023) who experimentally investigated the 𝒮 of TD data types measured in the DS arrangement.

3. Sensitivity Compendium

3.1. Definition of sensitivity

Consider an optically diffuse medium with some μa. This medium is measured by some optical measurement technique which yields 𝒴. If the μa of the medium changes, a change in 𝒴 will be measured. The Δμa may be global (i.e., homogeneous throughout the medium) or local at r with a perturbation volume (Vpert); we denote these two cases by Δμa,pert,homo and Δμa,pert(r), respectively. Furthermore, relationships between the measured changes in 𝒴 and Δμa are described by the global Jacobian ∂𝒴/∂μa,pert,homo and the local Jacobian ∂𝒴/∂μa,pert(r), respectively. 𝒮 is defined as the ratio of these local and global Jacobians,

If we remember that Δ𝒴 can be converted to a recovered Δμa,𝒴 using proportionality constants,38,49,k we can interpret Eq. (1) differently. Δμa,𝒴 represents the effective homogeneous Δμa which would cause the measured change in 𝒴. Considering this, 𝒮𝒴(r) can be written as follows :

By this definition of 𝒮, it may be positive or negative. This consideration of sign depends on the data type (𝒴) and perturbation location (r). We can interpret this by examining either Eq. (1) or Eq. (2). In Eq. (1), it can be seen that a negative 𝒮 corresponds to the local and global Jacobians having different signs. Different signs would mean that for the particular local perturbation considered, the 𝒴 changed in an opposite direction than it would have if the perturbation were global (e.g., a case with negative 𝒮 would be the one where a particular local increase in μa causes an increase in 𝒴 while a global μa increase would cause a decrease in 𝒴). As will be seen, this is common for data types that utilize spatial gradients of optical data, such as SS. We can arrive at a similar understanding from Eq. (2). Here, the story is identical to that of Eq. (1), where Eq. (2) is negative if the actual local perturbation (Δμa,pert(r)) and the recovered change (Δμa,𝒴) have opposite signs. The opposite signs could be interpreted as the measurement recovering an increase/decrease but the actual local perturbation being a decrease/increase. Either way, negative 𝒮 indicates that the measured effective and real/actual local Δμas changed in the opposite direction in terms of sign.

Appendix A.1 describes how we generate 𝒮 containing the values of 𝒮 based on Eq. (1) for the maps in Sec. 3.2.

3.2. Sensitivity maps

In the following subsections, we re-create the 𝒮 maps for various different NIRS data types and methods. The methods to generate a majority of the maps (i.e., unless otherwise specified) can be found in Appendices A.1–A.3 and our previous publications.35,38,41,66 All maps were created assuming a homogeneous semi-infinite medium with a μa of 0.011mm−1 (

Further, we repeat that almost all maps consider the same color scale so that they can be compared throughout the compendium. Additionally, unless otherwise specified, the 𝒮 values were generated using the perturbation DT (see

3.2.1. Continuous wave

In CW, changes in I relative to a baseline I can be converted to Δμa. This method is based on knowledge of 〈L〉 of the medium, which is often represented as the DPF method.43,67 We refer to methods of a measurement of Δμa using a single source and a single detector as SD.35,38 Therefore, the most basic type of NIRS measurement is named SD CW I in this review.

If multiple ρs are used to acquire I as a function of ρ in CW, temporal changes in the slope of ln(ρ2I) versus ρ can also be converted to Δμa.52 This method, which we refer to as SS,l depends on the knowledge of the derivative of the slope versus Δμa which is sometimes referred to as the DSF.35,38

Finally, one may also recover Δμa using the DS method.35,38 DS uses the same measurement of slope as SS but it employs a special symmetric arrangement of two sources and two detectors.48 As such, calculation of Δμa for DS is also dependent on the knowledge of DSF.

3.2.1.1. Single distance intensity

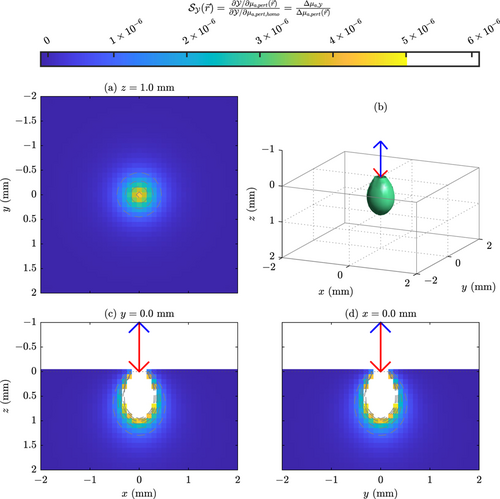

Figure 1 shows our first and most basic 𝒮 map. This map was generated with adjoint MC25,66,68 due to the small ρ considered of 0mm (see ‘simTyp’ of ‘MC’ in Listing A.2 and Appendix A.3). Figure 1 considers a perturbation of 0.1mm×0.1mm×0.1mm, thus the numerical values for 𝒮 are not comparable to those in the other figures which consider a larger perturbation.

Fig. 1. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 0.1mm×0.1mm×0.1mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW SD intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=1mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=3×10−5. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=0mm. Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; detector numerical aperature (NA): 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

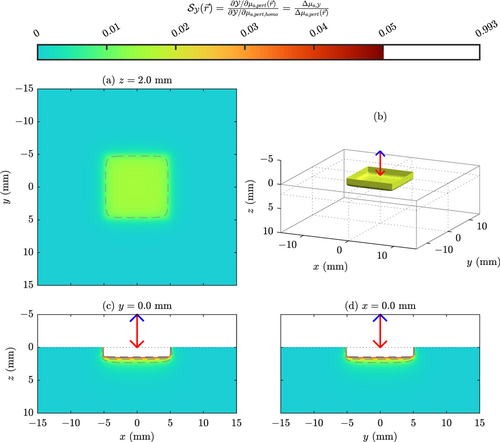

Next we show Fig. 2 which is also generated with adjoint MC,25,66,68 but this time with a perturbation of 10mm×10mm×2mm. Therefore, map’s color scale is comparable to most other figures in this review.

Fig. 2. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW SD intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=2mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=0mm. Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

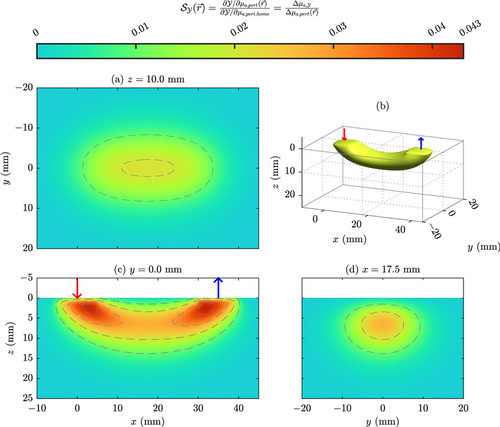

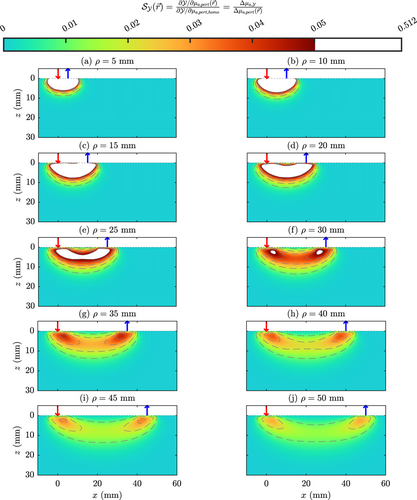

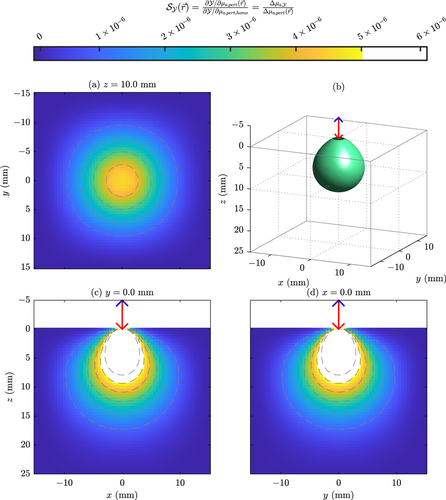

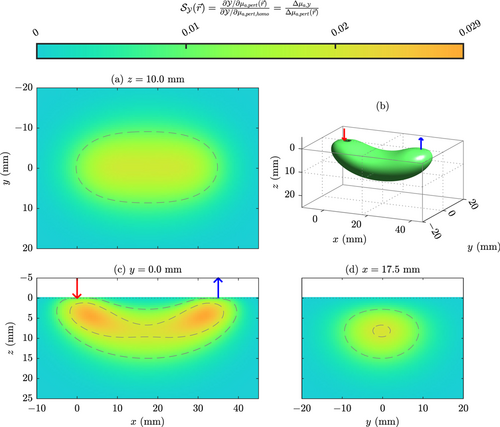

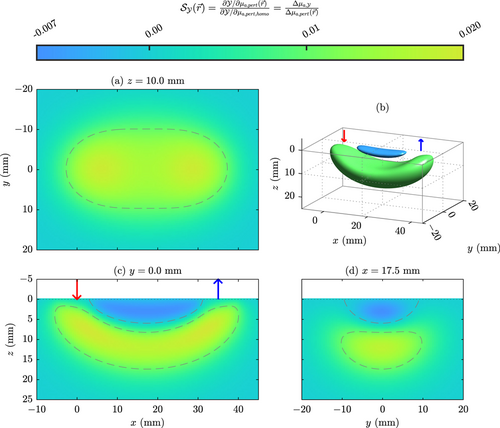

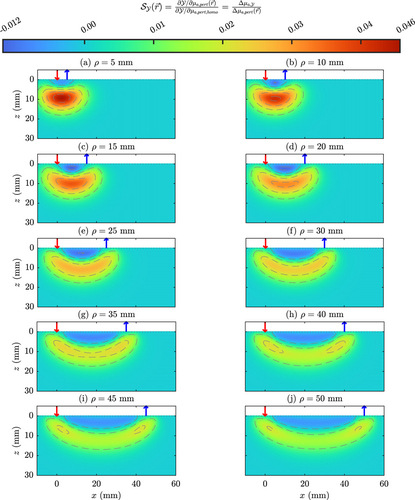

The classic banana shape8 emerges when we investigate 𝒮 for an SD measurement with a nonzero ρ. Figure 3 shows this case. Next, Fig. 4 shows CW SD I for 10 different values of ρ. Now that ρ is nonzero for Fig. 4, the map is calculated using an analytical DT model (see

Fig. 3. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW SD intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=17.5mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

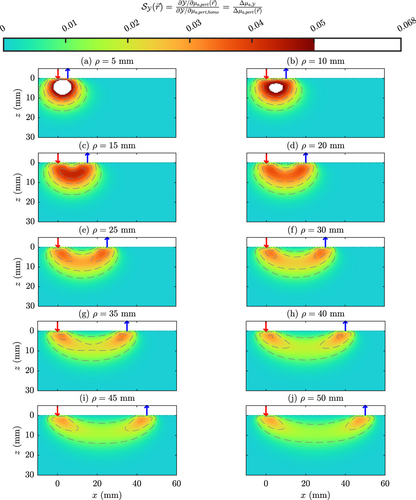

Fig. 4. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW SD intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of source-detector distance (ρ). Generated using DT. Here, index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

3.2.1.2. Spatially resolved intensity

Now we move to 𝒮 maps for the SS and DS methods. Figures 5 and 6 show the 3D volumes of these maps, while Figs. 7–10 show the maps for various ρs making up the SS or DS. The ρs in an SS or DS set can be described using ˉρ and Δρ as follows:

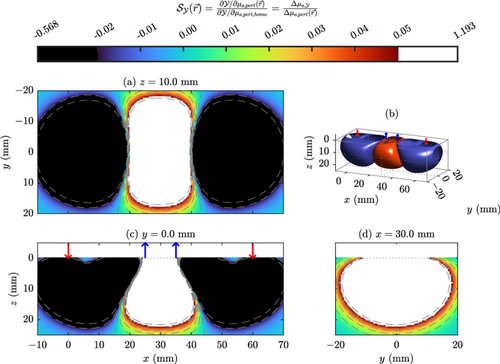

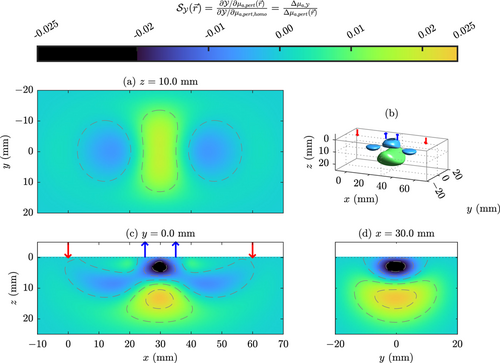

Fig. 5. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW SS intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020 and 𝒮=−0.010. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=20mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

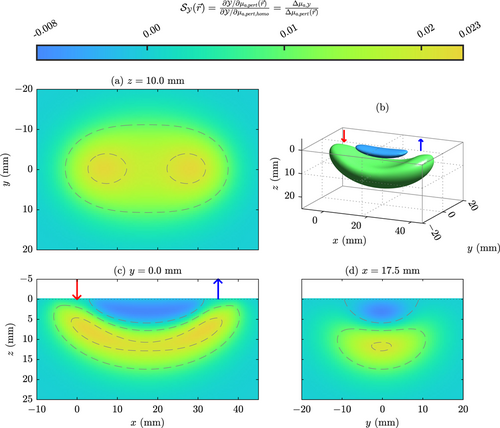

Fig. 6. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW DS intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020 and 𝒮=−0.010. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=30mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

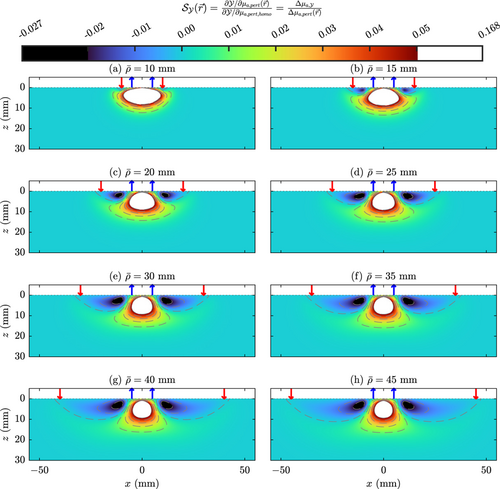

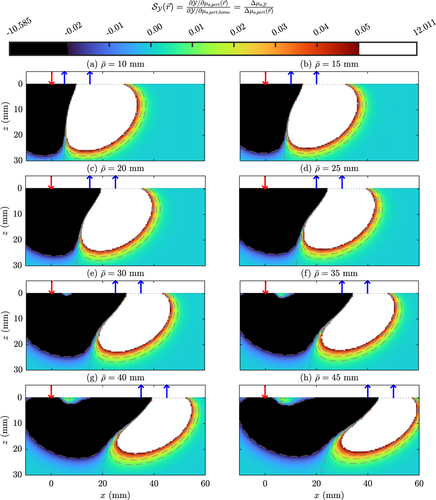

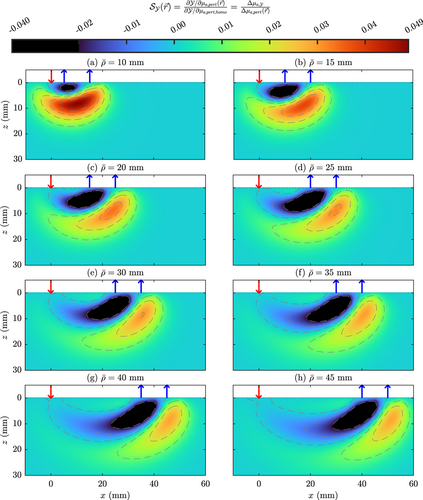

Fig. 7. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW SS intensity (I): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (ˉρ). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (Δρ): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

Fig. 8. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW DS intensity (I): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (ˉρ). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (Δρ): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

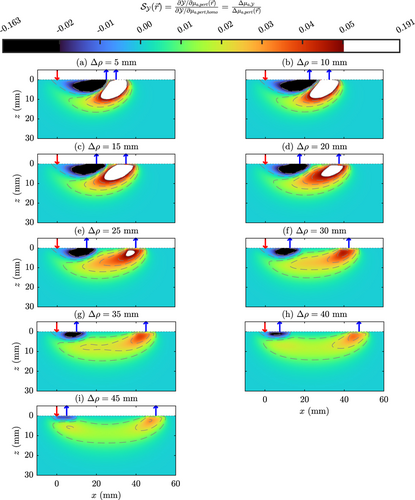

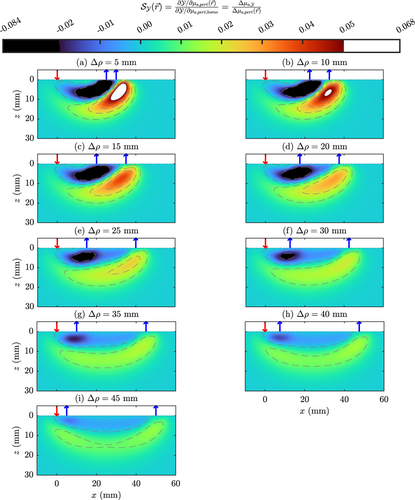

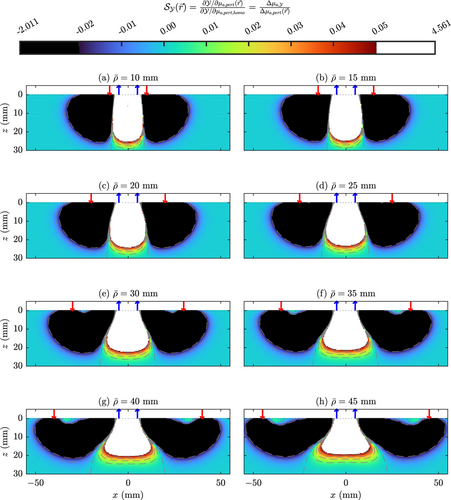

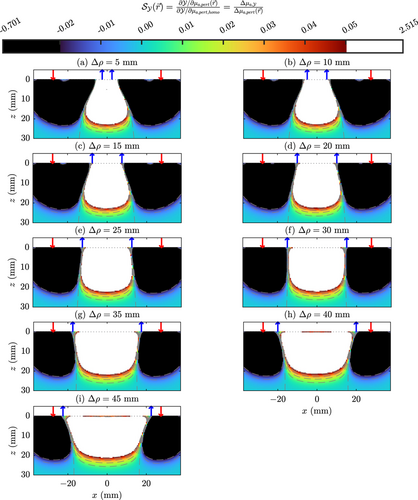

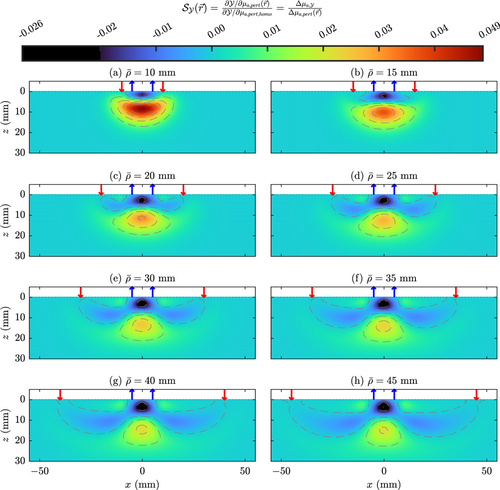

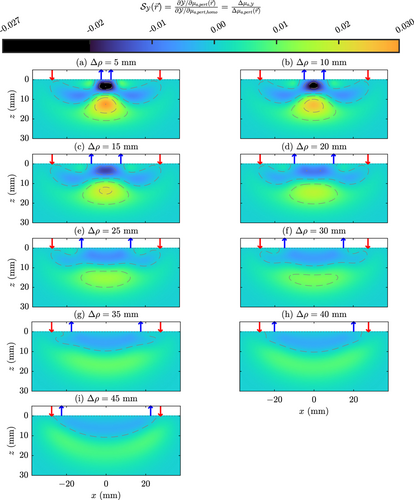

Fig. 9. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW SS intensity (I): (a)–(i) Different values of difference in source-detector distances (Δρ). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (ˉρ): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

Fig. 10. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by CW DS intensity (I): (a)–(i) Different values of difference in source-detector distances (Δρ). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (ˉρ): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

3.2.2. Frequency domain

Similar to CW, FD also measures an I data type. In FD, the I is the amplitude of the measured photon density waves. At low fmod (around 100MHz or below), FD I well estimates CW I41; as such, we do not show the same maps for FD I over various ρ, ˉρ, and Δρ that were already shown for CW I in Sec. 3.2.1. However, FD does utilize an additional parameter of fmod. For this reason, FD I is explored over fmod in this subsection.

The additional data type that FD gives access to is ϕ. ϕ can be used to recover Δμa in all the SD, SS, and DS measurement methods using a generalized 〈L〉 (Eq. (A.1)), generalized DPF (i.e., for SD), or generalized DSF (i.e., for SS or DS).38 As with all other maps, the methods to generate them can be found in Appendix A.1 and Listing A.1.

3.2.2.1. Single distance

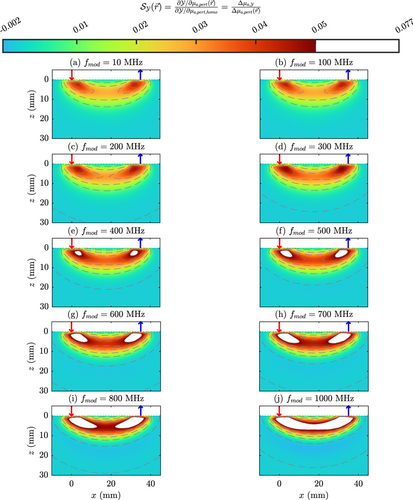

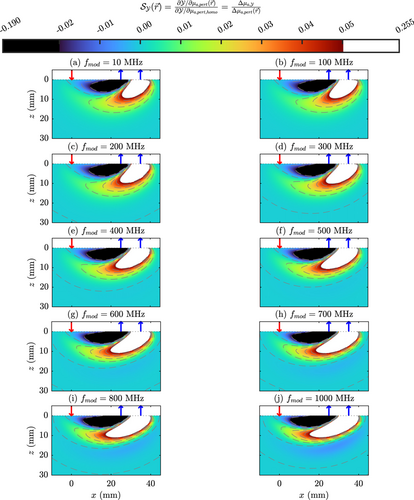

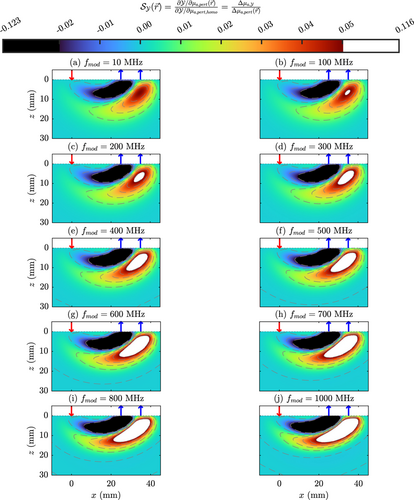

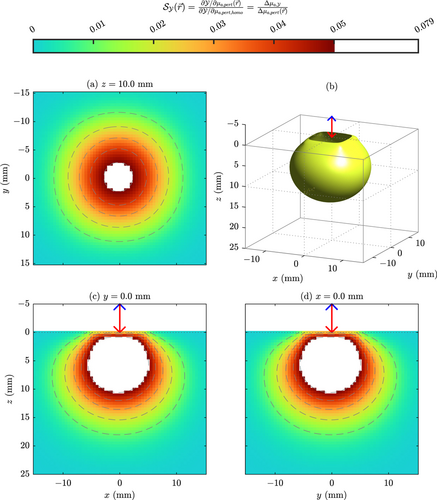

Intensity. Figure 11 shows the 3D 𝒮 volume for FD SD I. This is followed by Fig. 12 which shows the 𝒮 map over various fmod. Notice that at high fmod a negative 𝒮 for FD SD I is observed deep in the medium.31

Fig. 11. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SD intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=17.5mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 12. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SD intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of modulation frequency (fmod). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

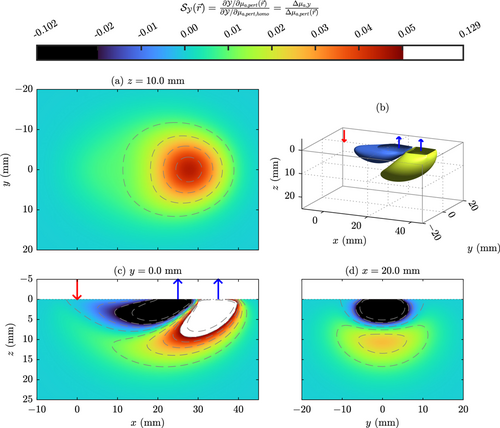

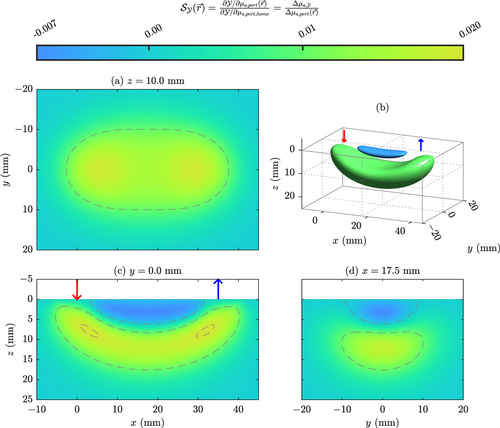

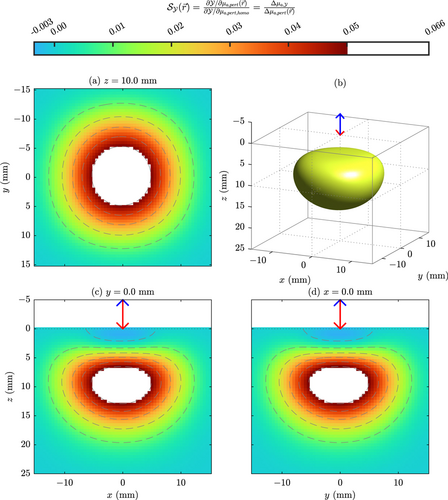

Phase of photo density waves. Figure 13 shows the 3D 𝒮 volume for FD SD ϕ; and Figs. 14 and 15 explore varying ρ and fmod, respectively.

Fig. 13. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SD phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.010 and 𝒮=−0.005. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=17.5mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 14. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SD phase of photon density waves (ϕ). (a)–(j) Different values of source-detector distance (ρ). Generated using DT. Here, index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 15. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SD phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a)–(j) Different values of modulation frequency (fmod). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

3.2.2.2. Spatially resolved

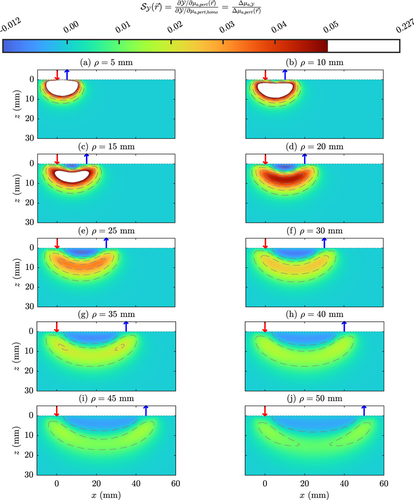

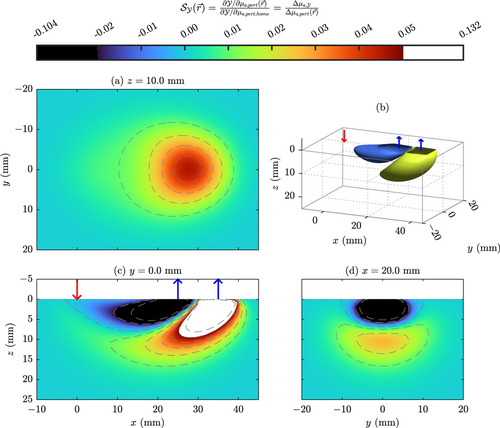

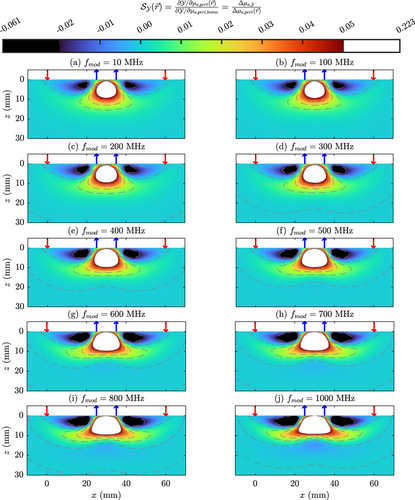

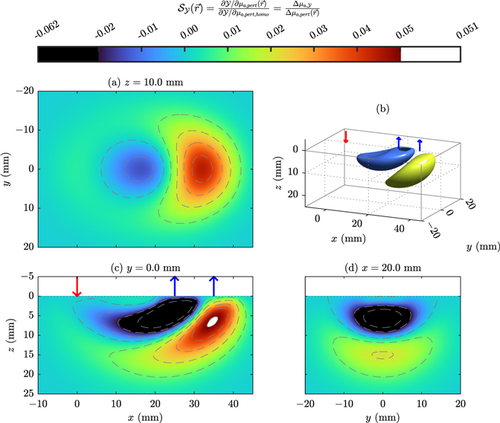

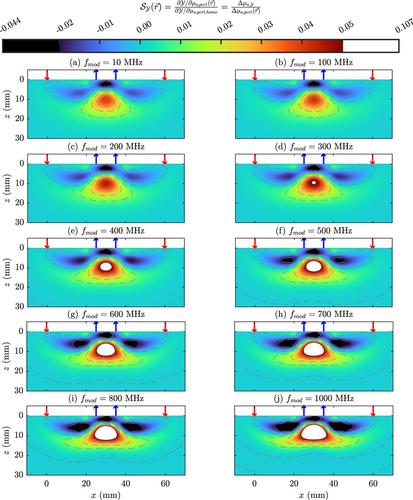

Intensity. Now we move to SS- and DS-type measurements for FD I. First, we show the example 3D volumes for SS and DS in Figs. 16 and 17. Then the case of SS or DS and their dependence on fmod is displayed in Figs. 18 and 19, respectively.

Fig. 16. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SS intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020 and 𝒮=−0.010. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=20mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 17. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD DS intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020 and 𝒮=−0.010. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=30mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 18. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SS intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of modulation frequency (fmod). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

Fig. 19. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD DS intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of modulation frequency (fmod). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

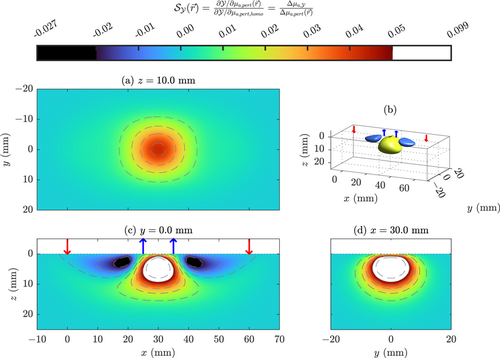

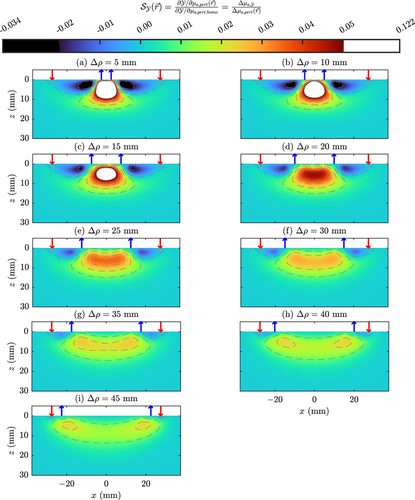

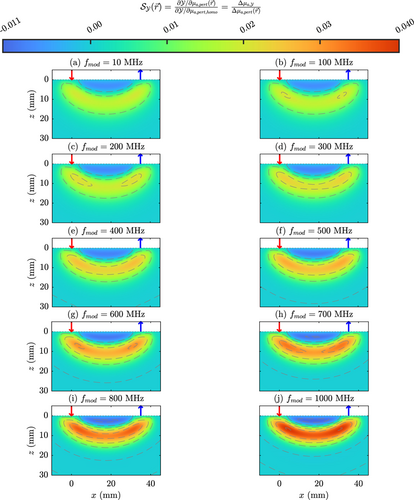

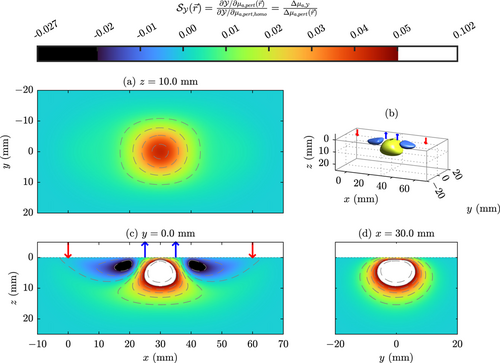

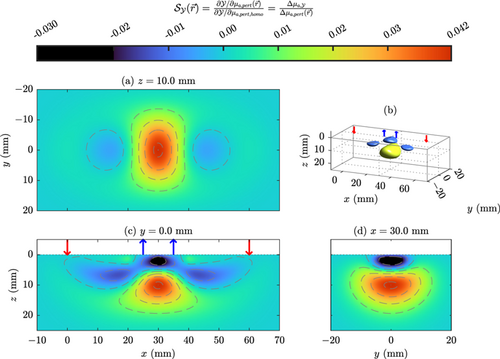

Phase of photo density waves. To finish our subsection on FD, we show the SS and DS 𝒮 maps for FD ϕ. First come the 3D volumes in Figs. 20 and 21. Then for varying ˉρ (Eqs. (3) and (4)) in Figs. 22 and 23; similarly, for various Δρ (Eqs. (5) and (6)) in Figs. 24 and 25. Finally, we explore different values of fmod for SS and DS in Figs. 26 and 27, respectively.

Fig. 20. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020 and 𝒮=−0.010. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=20mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 21. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD DS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020 and 𝒮=−0.010. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=30mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 22. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (ˉρ). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (Δρ): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 23. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD DS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (ˉρ). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (Δρ): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

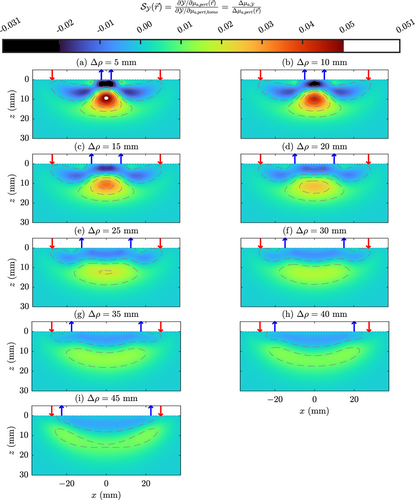

Fig. 24. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a)–(i) Different values of difference in source-detector distances (Δρ). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (ˉρ): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 25. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD DS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a)–(i) Different values of difference in source-detector distances (Δρ). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (ˉρ): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and modulation frequency (fmod): 100MHz.

Fig. 26. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD SS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a)–(j) Different values of modulation frequency (fmod). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

Fig. 27. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.1mm measured by FD DS phase of photon density waves (ϕ): (a)–(j) Different values of modulation frequency (fmod). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

3.2.3. Time domain

TD offers access to the most data types of any NIRS temporal domain.45 These TD data types can be split into two categories; those of the TPSF moments or time gated portions of the TPSF (i.e., gated TD I).37 All of these data types, whether SD or spatially resolved (i.e., SS or DS), can be used to measure Δμa by the same aforementioned methods (i.e., generalized 〈L〉) which utilize the derivative of the data type with respect to μa (Eq. (A.1)).41

The zeroth TD moment is the TD I and if the whole TPSF is considered, this moment is the same as CW I. Next is the first moment, 〈t〉; this moment is well approximated by FD ϕ.41,m Therefore, we will not show the nongated TD I (i.e., the integral of the whole TPSF) as it would be redundant with CW I and also not show TD 〈t〉 over ρ, ˉρ, and Δρ since it would be redundant with the FD ϕ𝒮 maps.

The data type related to the second moment is TD σ2, which will be reviewed in this subsection. We would like to note that the FD modulation depth (i.e., FD I which is an amplitude, divided by CW I) well approximates TD σ2.41 Similar to other data types, σ2 can be considered for SD, SS, and DS.34

The other category of TD data is the gated TD I (i.e., the gated TPSF). This measurement selects photons which have particular sets of path lengths. Additionally, a data type may be constructed which is a difference of the gated TD I from different gates.37 For example, subtracting early gated photon data from late gated, selects for 𝒮 of deep regions where the photons have longer paths. As with all else, we also review these 𝒮 maps for these data types applied to SD, SS, and DS.

3.2.3.1. Single distance

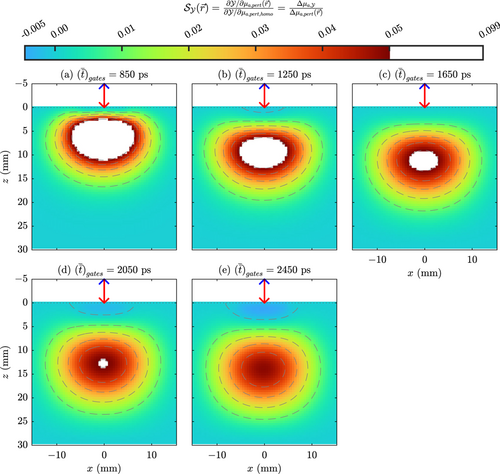

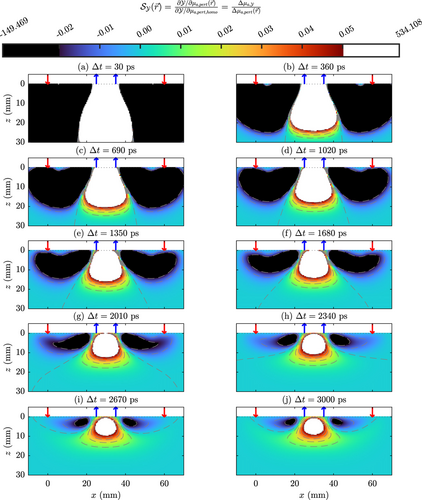

Gated intensity. Now, we begin the gated TD I subsection with the 3D 𝒮 volumes for null ρ (i.e., ρ=0mm) in Figs. 28 and 29. This is contrasted to the CW examples of null ρ in Figs. 1 and 2 since late TD gated I can yield relatively deep 𝒮 unlike CW.18 We follow the maps of null ρ with Fig. 30 which presents the 3D volume for a nonzero ρ. Finally, capping out the maps which show TD SD gated I at various ρs is Fig. 31 which explores various nonzero ρs in its subplots.

Fig. 28. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 0.5mm×0.5mm×0.5mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=3×10−5. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=0mm. Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 29. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=0mm. Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 30. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.010 and 𝒮=−0.005. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=17.5mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Fig. 31. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of source-detector distance (ρ). Generated using DT. Here, index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Next, we look at the 𝒮 map dependence on the gate t. To do this, we define the gate ˉt and the gate Δt as follows:

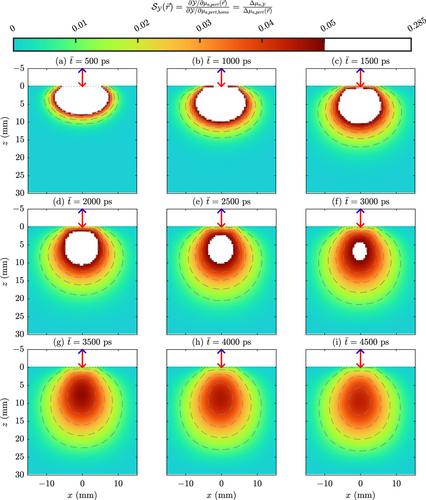

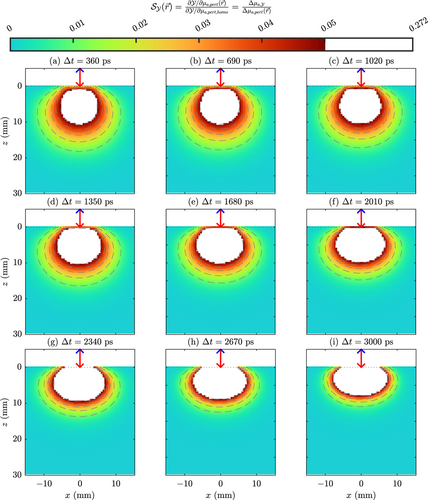

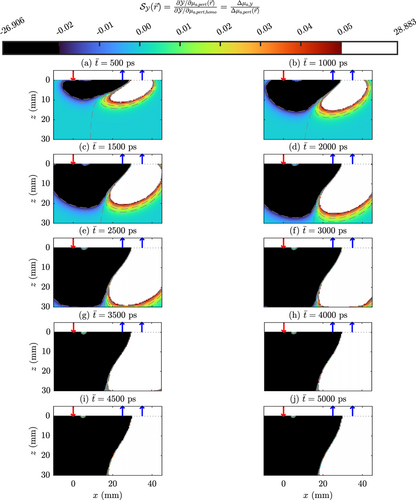

Fig. 32. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a)–(i) Different values of mean time (ˉt). Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; time difference (Δt) gate: 500ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 33. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of mean time (ˉt). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and time difference (Δt) gate: 500ps.

Fig. 34. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a)–(i) Different values of time difference (Δt). Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; mean time (ˉt) gate: 1750ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 35. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD gated intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of time difference (Δt). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and mean time (ˉt) gate: 1750ps.

Whenever considering TD SD gated I with a null ρ (Figs. 28, 29, 32, and 34), MC was used to generate the 𝒮 map (see

Mean of the photon time-of-flight distribution. As mentioned in the beginning of this subsection, we do not consider TD 〈t〉 as a function of the parameter ρ since it would be redundant with FD ϕ. However, to display an example of TD SD 〈t〉, we provide Fig. 36 which is the 3D volume of 𝒮.

Fig. 36. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD mean of the photon time-of-flight distribution (〈t〉). (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.010 and 𝒮=−0.005. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=17.5mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

Differences in gated intensities. Differences in I measured by different TD t gates may also be considered.37 Here, we first present this data type’s 3D 𝒮 volume for the null ρ (i.e., ρ=0mm) in Figs. 37 and 38; note that these figures present different perturbation sizes. Following the null ρ case, we show the nonzero ρ case’s 3D volume in Fig. 39; then the 2D map over various ρs in Fig. 40.

Fig. 37. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 0.5mm×0.5mm×0.5mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=3×10−5 and 𝒮=−1×10−5. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=0mm. Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; early time (t) gate: [500, 1000]ps; time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 38. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.020 and 𝒮=−0.010. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=0mm. Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; early time (t) gate: [500, 1000]ps; time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 39. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.010 and 𝒮=−0.005. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=17.5mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; early time (t) gate: [500, 1000]ps; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Fig. 40. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a)–(j) Different values of source-detector distance (ρ). Generated using DT. Here, index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; early time (t) gate: [500, 1000]ps; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

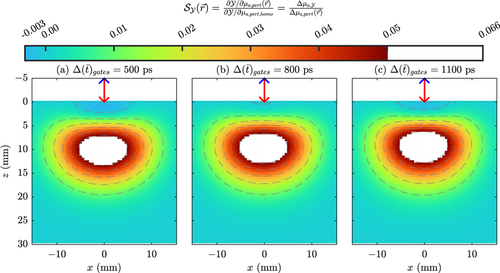

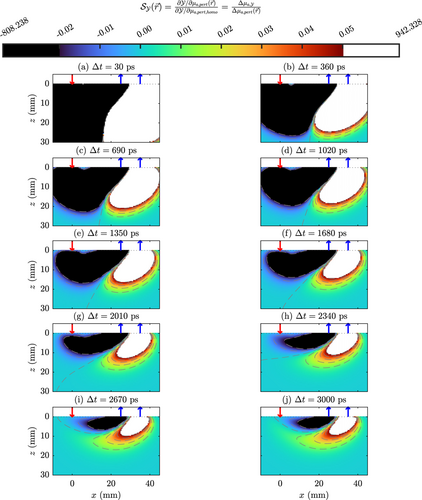

To begin investigating the dependence on late and early gate ts, we define ¯(ˉt)gates and Δ(ˉt)gates as follows:

Fig. 41. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a)–(e) Different values of average of gate center times (¯(ˉt)gates). Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; time difference (Δt) gates: 500ps; difference between gate center times (Δ(ˉt)gates): 1000ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 42. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a)–(j) Different values of average of gate center times (¯(ˉt)gates). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; time difference (Δt) gates: 500ps; and difference between gate center times (Δ(ˉt)gates): 1000ps.

Fig. 43. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a)–(c) Different values of difference between gate center times (Δ(ˉt)gates). Generated using MC. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 0mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; scattering anisotrophy (g): 0.9; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; time difference (Δt) gates: 500ps; average of gate center times (¯(ˉt)gates): 1250ps; detector NA: 0.5; and number of photons: 109.

Fig. 44. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD difference in gated intensities I: (a)–(i) Different values of difference between gate center times (Δ(ˉt)gates). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; time difference (Δt) gates: 500ps; and average of gate center times (¯(ˉt)gates): 1250ps.

Whenever considering the TD SD difference in gated I with a null ρ (Figs. 37, 38, 41, and 43), MC was used to generate the 𝒮 map (see

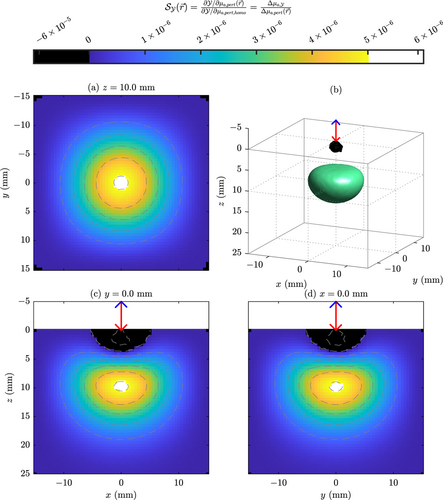

Variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution. An additional data type that TD gives access to is σ2. We show the TD SD σ2 3D 𝒮 volume in Fig. 45. Then we finish the TD SD subsection with the TD SD σ2 investigated over various ρs in Fig. 46.

Fig. 45. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (σ2): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.010 and 𝒮=−0.005. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=17.5mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distance (ρ): 35mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

Fig. 46. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SD variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (σ2): (a)–(j) Different values of source-detector distance (ρ). Generated using DT. Here, index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; and absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1.

3.2.3.2. Spatially resolved

Now, we review the 𝒮 maps for SS and DS in TD. We do this for the data types of t gated I, 〈t〉, and σ2 in the following.

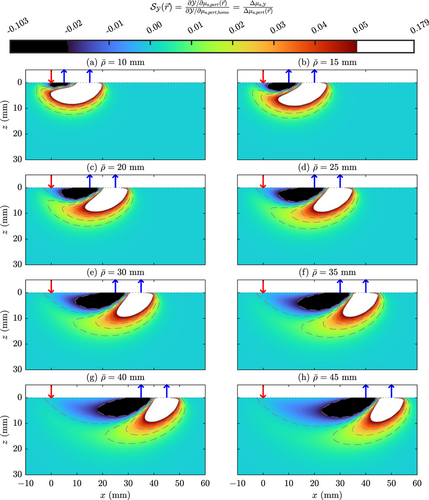

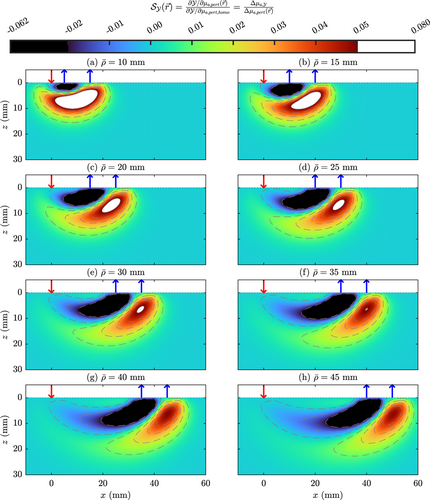

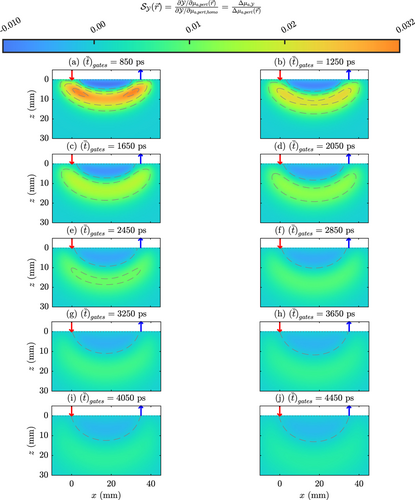

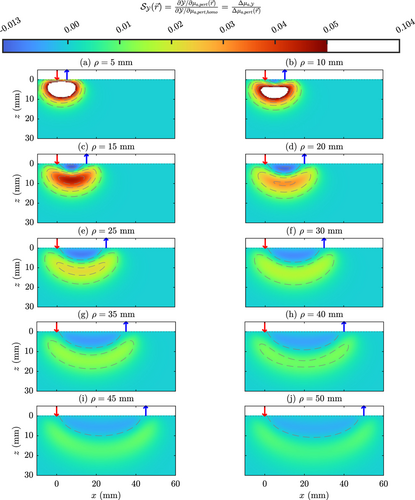

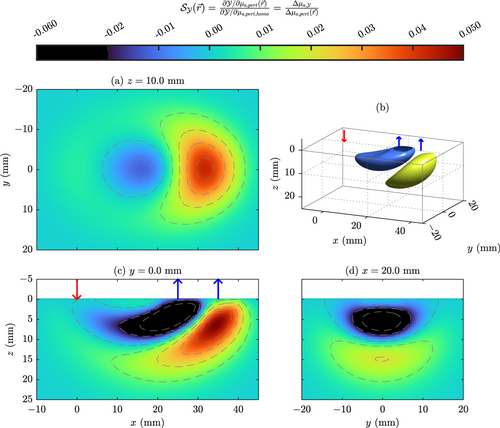

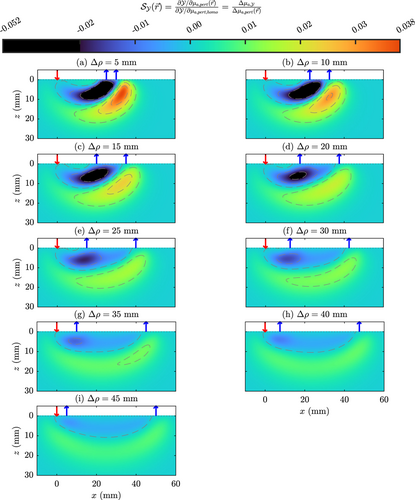

Time gated intensity. We show plots of the 3D 𝒮 for SS and DS TD gated I in Figs. 47 and 48, respectively. Then, SS and DS TD gated I over various ˉρs (Eqs. (3) and (4)) are shown in Figs. 49 and 50, respectively. This is followed by plots over various Δρs (Eqs. (5) and (6)) in Figs. 51 and 52, respectively.

Fig. 47. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change (𝒮) to a 10mm×10mm×2mm perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS gated intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at z=10mm. (b) Iso-surface sliced at 𝒮=0.040 and 𝒮=−0.015. (c) x–z plane sliced at y=0mm. (d) y–z plane sliced at x=20mm. Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (ρs): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (μ′s): 1.10mm−1; absorption coefficient (μa): 0.011mm−1; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Fig. 48. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS gated intensity (I): (a) x–y plane sliced at . (b) Iso-surface sliced at and . (c) x–z plane sliced at . (d) y–z plane sliced at . Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Fig. 49. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS gated intensity (I): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Fig. 50. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS gated intensity (I): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Fig. 51. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS gated intensity (I): (a)–(i) Different values of difference in source-detector distances (). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

Fig. 52. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS gated intensity (I): (a)–(i) Different values of the difference in source-detector distances (). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and time (t) gate: [1500, 2000]ps.

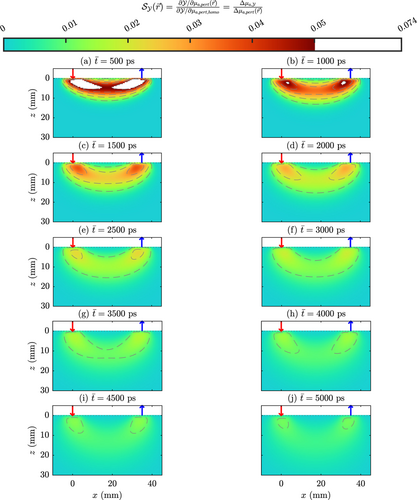

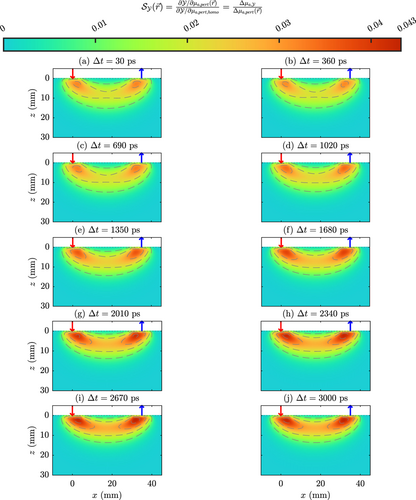

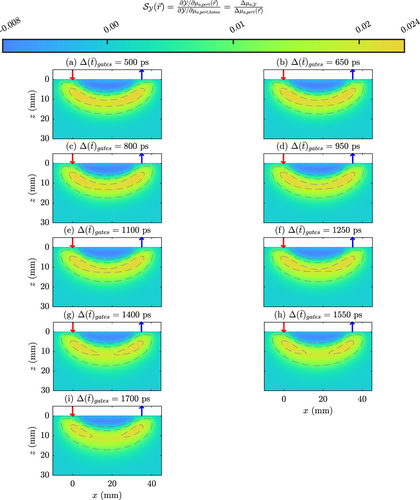

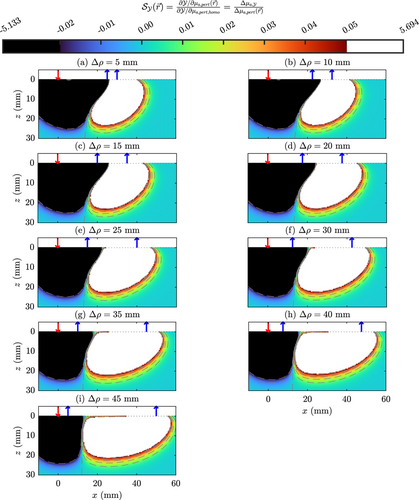

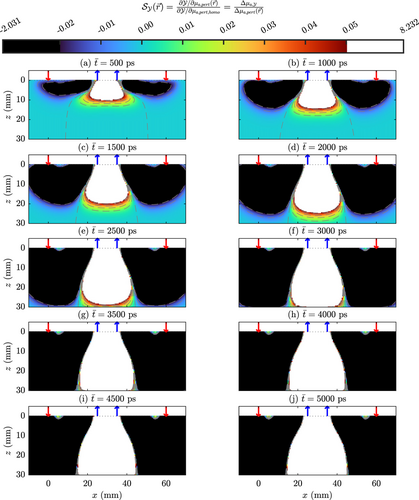

Following the maps which investigate spatial parameters are the ones which vary over the temporal parameters (Eq. (7)) and (Eq. (8)). Figures 53 and 54 show the maps over for SS and DS, respectively. Finally, we have Figs. 55 and 56 which vary over in their various subplots for SS and DS, respectively.

Fig. 53. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS gated intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of mean time (). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and time difference () gate: 500ps.

Fig. 54. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS gated intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of mean time (). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and time difference () gate: 500ps.

Fig. 55. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS gated intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of time difference (). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and mean time () gate: 1750ps.

Fig. 56. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS gated intensity (I): (a)–(j) Different values of time difference (). Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; absorption coefficient (): ; and mean time () gate: 1750ps.

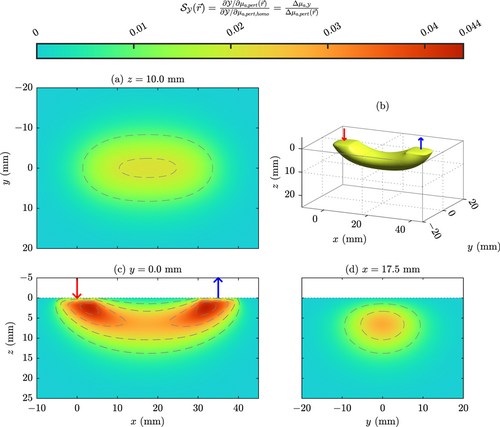

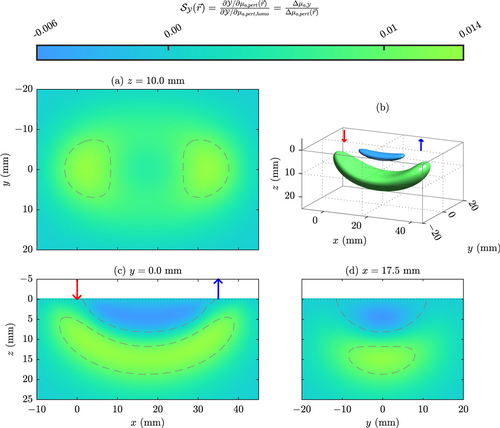

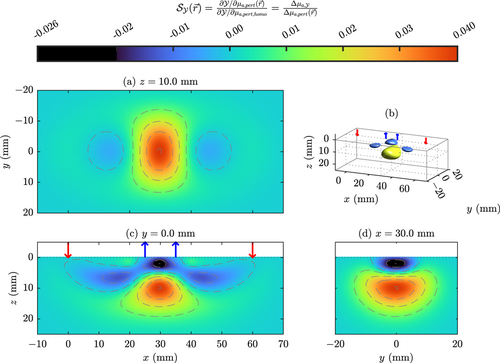

Mean of the photon time-of-flight distribution. As mentioned before in this subsection, plotting TD over and would be redundant with the plots presented for FD . However, we still present the SS and DS TD 3D volumes in Figs. 57 and 58, respectively.

Fig. 57. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS mean of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a) x–y plane sliced at . (b) Iso-surface sliced at and . (c) x–z plane sliced at . (d) y–z plane sliced at . Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

Fig. 58. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS mean of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a) x–y plane sliced at . (b) Iso-surface sliced at and . (c) x–z plane sliced at . (d) y–z plane sliced at . Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

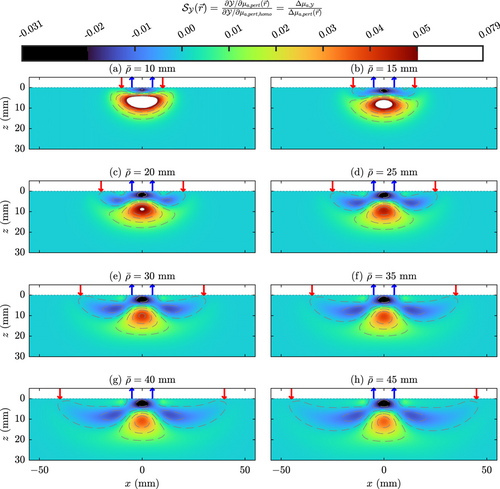

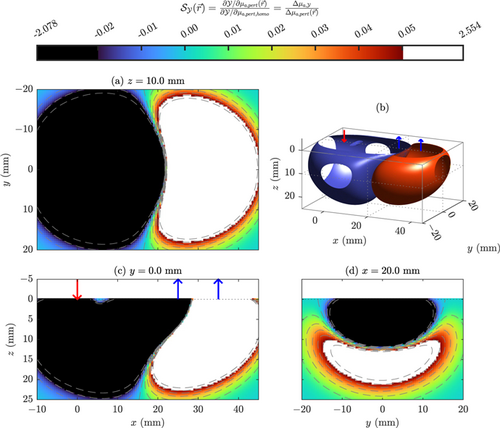

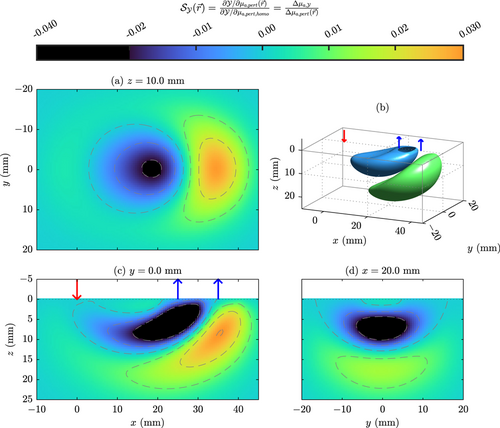

Variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution. The final set of maps we review in this work are the ones for SS and DS TD . The first of this set is the 3D volumes in Figs. 59 and 60, respectively. We then show the 2D maps with the varying spatial variables (Eqs. (3) and (4)) and (Eqs. (5) and (6)). Figures 61 and 62 explore various for SS and DS, respectively. Finally, Figs. 63 and 64 explore various for SS and DS, respectively.

Fig. 59. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a) x–y plane sliced at . (b) Iso-surface sliced at and . (c) x–z plane sliced at . (d) y–z plane sliced at . Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

Fig. 60. Third angle projection of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a) x–y plane sliced at . (b) Iso-surface sliced at and . (c) x–z plane sliced at . (d) y–z plane sliced at . Generated using DT. Here, source-detector distances (): [25, 35, 35, 25]mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

Fig. 61. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

Fig. 62. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a)–(h) Different values of mean source-detector distance (). Generated using DT. Here, difference in source-detector distances (): 10mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

Fig. 63. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD SS variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a)–(i) Different values of difference in source-detector distances (). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

Fig. 64. x–z plane of the sensitivity to local absorption change to a perturbation scanned 0.5mm measured by TD DS variance of the photon time-of-flight distribution (): (a)–(i) Different values of difference in source-detector distances (). Generated using DT. Here, mean source-detector distance (): 27.5mm; index of refraction (n) inside: 1.333; index of refraction (n) outside: 1; reduced scattering coefficient (): ; and absorption coefficient (): .

4. Conclusion

This compendium of seeks to provide the reader with a single document containing spatial maps for a large variety of NIRS methods. Importantly, all maps present for the same background optical properties and for the majority, the same perturbation size. Additionally, almost all maps are presented on the same color scale so that they may be compared. If a reader wishes to recreate or generate these maps for themselves, they can find the MATLAB code available in A (primarily in Listing A.1) and at Ref. 50.

We want to emphasize that when interpreting these maps, one should consider realistic experimental conditions — for example, detector sensitivity and dynamic range control what are possible. Further, instrument noise influences what perturbations (considering size and amplitude) can be recovered in the optical measurement. Some of these considerations may be taken by converting the maps to SNR maps.35,38,41 We did not present the SNR maps here to keep this work instrument agnostic.

These methods and representations of can be expanded beyond what is considered here in future work. For example, one may define sensitivities to perturbations instead of . Furthermore, additional techniques and measurement types can be considered. These could include Diffuse Correlation Spectroscopy (DCS) or Spatial-Frequency-Domain Imaging (SFDI). Regardless, there are a plethora of future works which can be done to understand spatial sensitivities of diffuse optical measurements.

In addition to the collection of maps, we also created a timeline of relevant works that presented in the history of NIRS research. This set of references serves as a representation of the previous works to generate maps, which this review recreates. We hope that this paper serves as a go-to reference to visualize maps for a large variety of NIRS data types.

Code Availability

Supporting code can be found in Appendix A and accessed at the following link50: https://github.com/DOIT-Lab/DOIT-Public/tree/master/SensitivityCompendium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01-EB029414. Giles Blaney would like to acknowledge funding from the NIH Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Awards (IRACDA) Program Grant K12-GM133314. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the awarding institutions.

Appendix A

A.1. Calculation of sensitivity

Listing A.1 shows the main MATLAB function used to generate . This code allows one to input the data type along with the requisite parameters and returns a 3D (

Depending on the data type a different function is needed to calculate and . The handling of choosing the correct or functions can be found in the case structure starting in the following line in Listing A.1:

Functions for

|

A.1.1. Generalized path length

It may be helpful to express the Jacobians with respect to as normalized which we name the generalized optical path lengths for . These path lengths all have units of length but are only real path lengths in the cases of CW I and TD I. In the global case, the generalized is defined as follows :

Now using these definitions of generalized path lengths, we can rewrite Eq. (1) as

Also note that we can use this concept of to write the recovered as

A.1.1.1. Sensitivity of differences

Various data types utilize the differences of measurements such as SS and DS which are based on spatial differences or differences in TD gated I which are temporal differences. In either of these cases, Eq. (1) can be used to find for the data type. However, we may also write for the difference data types in terms of the generalized path lengths of the data for which the difference is being taken. For example, in SS a difference is taken between a long and a short and the of SS can be expressed in terms of the general path lengths of the SD long and SD short .

This of differences between and is expressed in the following way :

Furthermore, DS is a special case since it is an average of differences.35,38 Consider a DS with four measurements , , , and , where even subscripts are short and odd long . Then, for DS can be written as

A.1.2. Applying the perturbation size

Listing A.1 first calculates the for each voxel (

Therefore, one may say that the

A.2. Diffusion theory

A.2.1. Perturbation theory

A.2.1.1. Global Jacobian functions

Continuous wave

|

Frequency domain

|

Time domain

|

|

|

A.2.1.2. Local Jacobian functions

Continuous wave

|

Frequency domain

|

Time domain

|

|

|

A.2.2. Forward functions

A.2.2.1. Continuous wave

|

A.2.2.2. Frequency domain

|

|

A.2.2.3. Time domain

|

|

|

|

A.3. Monte Carlo

|

|

|

A.4. Other supporting MATLAB functions

|

|

|

|

ORCID

Giles Blaney  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3419-4547

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3419-4547

Angelo Sassaroli  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4233-7165

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4233-7165

Sergio Fantini  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5116-525X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5116-525X

Notes

a Cases where the photons enter and exit the medium at the same location have also been considered.

b Photon visitation probability is the probability that a photon emitted from the source and detected by the detector visited a spatial location within the diffuse medium.

c Note that DS has further requirements on the arrangement of optodes beyond simply a measurement of optical data across .36,48

d This is ensured by the use of the correct proportionality factor (i.e., DPF or DSF) for the data type .

e FD I reduces to CW I in the case of being zero.

f The from TD can be approximated by in FD.41

g The from TD can be approximated by FD I normalized by CW I.41

h For an infinitely large t gate of TPSF, TD I is equivalent to CW I.

i The average time a photon spends in each voxel (proportional to ) normalized by (proportional to ) is for CW I, for other data types the distribution of photon voxel times and photon arrival times must be considered to yield .41

j A work that considers advanced temporal domains (i.e., TD or FD) either is assumed to have the information to/did consider lower temporal domains. That is, TD papers contain information necessary to consider FD and CW, while FD papers contain the necessary information to consider CW.

k These proportionality constants are the DPFs or DSFs which must be either assumed or calculated using the known absolute and of the medium.

l SS is sometimes also referred to as SRS.

m is approximated by FD via using the following relation: .

n Complex path lengths are named such since the mathematical expressions for these path lengths are the same as the physical Photon Path length in CW except that is substituted for where the additional variables are the , the n in the medium, and the c.