Tunable absorption characteristics in multilayered structures with graphene for biosensing

Abstract

Graphene derivatives, possessing strong Raman scattering and near-infrared absorption intrinsically, have boosted many exciting biosensing applications. The tunability of the absorption characteristics, however, remains largely unexplored to date. Here, we proposed a multilayer configuration constructed by a graphene monolayer sandwiched between a buffer layer and one-dimensional photonic crystal (1DPC) to achieve tunable graphene absorption under total internal reflection (TIR). It is interesting that the unique optical properties of the buffer-graphene-1DPC multilayer structure, the electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT)-like and Fano-like absorptions, can be achieved with pre-determined resonance wavelengths, and furtherly be tuned by adjusting either the structure parameters or the incident angle of light. Theoretical analyses demonstrate that such EIT- and Fano-like absorptions are due to the interference of light in the multilayer structure and the complete transmission produced by the evanescent wave resonance in the configuration. The enhanced absorptions and the huge electrical field enhancement effect exhibit potentials for broad applications, such as photoacoustic imaging and Raman imaging.

1. Introduction

Two-dimensional materials have been intensely investigated for their wide applications in biomedicine.1,2 Specifically, the unique properties of graphene have enabled applications in numerous technological areas. As an example, the fast and broadband optical absorption features of graphene have benefited many novel optoelectronic and biosensing applications.3,4 The desired properties of graphene in these applications mainly include three aspects. First, strong optical absorption from the graphene layers is sought for as it is directly related to the performance of imaging camera,5 coherent absorption,6 photoacoustic imaging,7 and photothermal therapy applications.8,9 To overcome the low absorption challenge of single-layer graphene, many approaches have recently been proposed, such as one-dimensional photonic crystal (1DPC),10 microcavity with mirrors,11 the gratings12 and the graphene ribbon array.13 Second, different absorption line shapes are desired. In the above-mentioned structures, light recycle of photon interference at a resonant wavelength is the basic principle to increase the absorption, causing all absorbing responses to have Lorentzian line shapes. In fact, the phenomenon of electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) found in quantum optical systems has been realized in classical optical structures such as microtoroid,14 metamaterials,15 and terahertz waveguide16 for applications of sensor, filter, slow light, and logic processing. Also, all optical analog EIT has been experimentally achieved by 1D coupled photonic crystal microcavities.17 On the other hand, Fano resonance with asymmetric line shape is widely investigated in plasmonic systems for its high sensitivity and figure of merit.18 Third, tunable optical absorption in the near-infrared regime and multi-wavelength operation is desired in graphene-based devices19,20; the tunability and multi-wavelength operation allow good match with the laser sources of different wavelengths, while the resultant electrical field enhancement at desired position can be applied for surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS)-based biosensing.21 In configurations reported earlier,22 however, it is challenging to tune the absorption properties after the structure is fabricated.

In this work, we propose a configuration of a graphene monolayer sandwiched between a buffer layer and 1DPC multilayer. The resultant tunable multichannel absorption property is investigated under the total internal reflection (TIR) condition. Meanwhile, by utilizing the evanescent wave resonance in the 1DPC, the EIT-like and Fano-like absorption is implemented at desired resonance wavelengths due to the interference of light in the proposed configuration. It is shown that the absorption characteristics of the configuration, including the absorption peak positions, widths, intensities, number of the peaks, and the interval between adjacent peaks, are all adjustable without engineering the graphene monolayer. Such a property may find wide use to improve the performances of graphene-based devices and furtherly extend their applications in biosensing.

2. Structure Model and Principle

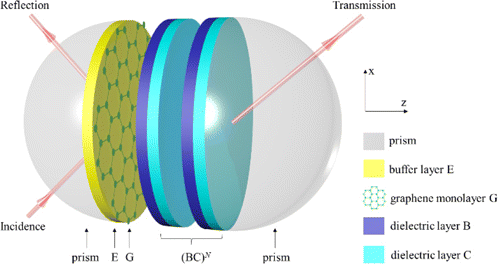

Similar to the EIT phenomenon in an atomic system, in our configuration two “atoms” should be constructed, including one broadband “Atom 1” (bright state) being absorbed and one narrowband “Atom 2” (dark state) being transmitted. The EIT-like and Fano-like absorption then can be obtained by detuning the central wavelength of the narrowband transmission peak from that of the broadband absorption. The characteristics of such two-atom configuration, i.e., the buffer-graphene-1DPC multilayer structure, are discussed herein with a schematic shown in Fig. 1. In this system, “Atom 1” realizing the broadband absorption is constructed by designing a multilayer structure producing light interference. The complete absorption is achieved in such a multilayer structure that contains a layer of graphene as the absorption material. On the other hand, the transmission and the reflection of the whole structure are separately engineered to be zero based on the TIR and destructive interference experienced by the reflected light at all layer interfaces,23 and the position of the broadband absorption peak can be optimized with the help of the transfer matrix method.24 As for “Atom 2”, the narrowband transmission is enabled by a periodic structure like the 1DPC that produces the evanescent wave resonance. A perfect narrowband transmission is obtained when the evanescent wave resonance is formed in the low-index dielectric layers under the TIR. In an infinite periodic dielectric multilayers (BC)N alternately composed by a layer of high refractive index (B) and a layer of low refractive index (C), the propagation of light satisfies the following equation based on the Bloch theory25:

Fig. 1. Schematic of the structure of buffer-graphene-1DPC multilayer. The evanescent wave is coupled into the structure through the prism or the surface of an oblique cross-section of a fiber under TIR.

The absorption characteristics of the one-dimensional dielectric multilayers can be investigated based on the above-mentioned transfer matrix method.24,25 The propagation of light in the one-dimensional multilayer structure with homogeneous materials can be expressed with the production of the matrices for each layer. The transmission matrix for jth layer can be written as

3. Results and Discussion

To illustrate the validity of the above principle, a typical buffer-graphene-1DPC multilayer structure EG(BC)2 is presented for achieving the EIT-like and Fano-like absorption performance. The two half-sphere prisms are used to couple light based on a model proposed by Kretschmann.26 The advantage of using such a scheme is that the polarization response of the configuration can also be investigated if needed. It should be pointed out that prisms of other shapes, such as triangular27 and half-cylinder,28 can also be used. The structure parameters are set as follows: the thickness of the G layer dg=0.34nm and its optical refractive index ng=3+iλC1/3, where C1=5.446μm−1,3 the refractive indexes of B and C layers are respectively nb=3.48 and nc=1, and the buffer layer E is a low-index layer with a refractive index ne=1. Specifically, the optimal thicknesses of B, C and E layers in the structure EG(BC)2 are separately db=269nm, dc=500nm, and de=220nm, which are selected to get the perfect absorption of the structure by making the transmission and reflection to be zero under TIR in mid-infrared electromagnetic region. The size of the configuration in the transverse directions theoretically can be infinite.29 For practical fabrication, according to the reported works, one-dimensional multilayered configuration of centimeter long in the transverse directions can work for investigations within an area ∼100×100μm2.30,31 In addition, the graphene monolayer with a practical area of ∼0.5×0.5mm2 has been experimentally reported.32

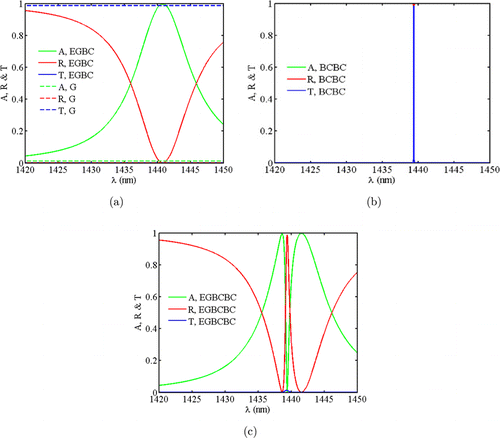

Figure 2 shows the absorption (A), reflection (R), and transmission (T) of the two composited “atoms” (EGBC and BCBC) as well as the whole structure EG(BC)2 with incident angle θ=60∘ under TE polarization. From Fig. 2(a), a highly enhanced broadband absorption is observed in the structure EGBC comparing with the 2.3% absorption of graphene monolayer. In Fig. 2(b), the perfect transmission is achieved when the evanescent resonance is formed in the BCBC structure; both absorption and reflection are zero at the resonant wavelength λ=1439nm. And, as shown in Fig. 2(c), the EIT-like absorption is achieved by EG(BC)2 structure at the dark state wavelength λ=1439nm. This confirms that the formation mechanism of the EIT-like absorption is the combination of the highly enhanced absorption caused by the light interference in the EGBC multilayer and the narrowband perfect transmission caused by the evanescent wave resonance in the 1DPC. This principle to get the EIT-like absorption is different from those reported in the references.14,15,16,17 Moreover, the position and the width of the absorption tip (dark state) can be adjusted by altering the thickness of layer B and C, respectively.

Fig. 2. The absorption (A), reflection (R) and transmission (T) spectra of the structure (a) EGBC, (b) BCBC, and (c) EG(BC)2 under TIR, respectively. The absorption (A), reflection (R), and transmission (T) of graphene monolayer are also plotted in (a) for comparison (dash line).

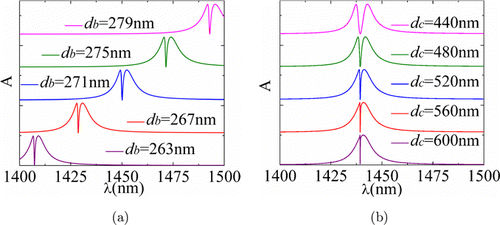

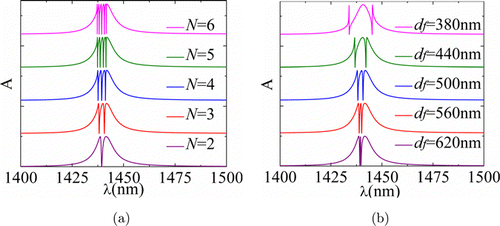

As displayed in Fig. 3, the positions of the absorption tips occur redshift as increasing db (Fig. 3(a)), and the widths of the absorption tips decrease as increasing the thickness dc (Fig. 3(b)). In addition, the number of the absorption tips and the interval between adjacent tips can also be changed by varying the periodic number N and the thickness of the C layer in the middle unit of the 1DPC (denoted as defect layer F), respectively, as shown in Fig. 4. From Fig. 4(a), there are N−1 absorption tips for 1DPC with N periods. From Fig. 4(b), the interval between the adjacent absorption tips increases with reduced thickness of the defect layer df. And the Fano-like absorption is gradually obtained (for df smaller than about 400nm) during the increase of the wavelength detuning between the two “atoms”. Moreover, the influence of different thicknesses df of the defect layer F on the spectrum response has also been checked in the structure EG(BC)mBF(BC)m (the total period N=2m+1, m=2, 3). It is noted that the case for m=1 is given in Fig. 4(b). It is found that that the number of the tips is 2m when the thickness of F is 500nm. With increased df, the number of tips gradually changes to m main sessions. The interval between the main sessions is defined as the “external interval”, and the interval between the two tips within each main session is referred to as the “internal interval”. Therefore, the external intervals decrease and the internal intervals increase with reduced df.

Fig. 3. The layer thickness-dependent absorption in the structure with N=2: (a) layer B and (b) layer C. The maximum absorptivity is 1 for all curves.

Fig. 4. The absorption as a function of wavelength λ, with relating to (a) the period N of 1DPC and (b) the thickness of defect layer F of structure EGBCBFBC, respectively.

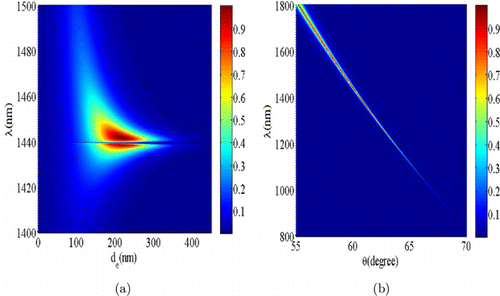

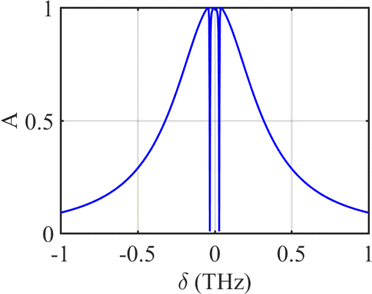

As shown in Fig. 5, the absorption of the structure EG(BC)2 can be changed by adjusting either the thickness of the buff layer E or the incident angle of light. From Fig. 5(a), an optimized thickness de=220nm is found to obtain the complete absorption of “atom 1”. The perfect transmission caused by the evanescent wave resonance always exists in the structure and is almost independent of the thickness de. From Fig. 5(b), a tradeoff is found between the maximum value of the absorption and the width of the absorption tip. That is, with increased incident angle, the absorption decreases linearly but the tip becomes narrower. The angular-sensitive response of the proposed structure is a significant advantage for designing a good performance directional filter and sensor. For example, the angular-sensitive response is calculated to be ∼70nm/degree, i.e., ∼4010nm/radian, for wavelength from 1100nm to 1800nm, with an incident angle from 55∘ to 65∘.

Fig. 5. The absorption map of the structure EG(BC)2 for (a) A (de, λ) and (b) A (θ, λ). The color bar indicates the absorption value.

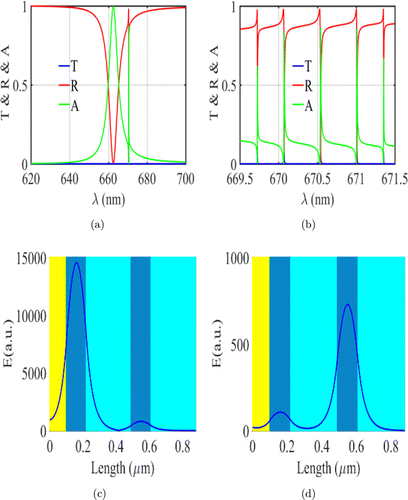

Moreover, the configuration can work in both near-infrared and visible regimes. By properly changing the materials and the geometry parameters of the configuration, the operation wavelength can be transited. At the same time, as demonstrated above, the structure parameters can be selected to make the central wavelength of “atom 2” a little far from that of “atom 1”, which will result in a Fano-like absorption. Figure 6(a) shows single Fano-like absorption at visible region, and the number of the absorption peaks can be changed by varying the period number N of structure BC. Same as the case of EIT, there are N−1 peaks for period number N. Figure 6(b) shows the absorption responses of structure EG(BC)6 are linear and have five ultra-narrow Fano-like absorption peaks. The full width at half maximum Δλ is about 9pm for the middle peak at λ=670.54nm, which corresponds to the quality factor of 7.45×104 calculated from λ/Δλ. It is very useful for designing of high-sensitive sensor and ultra-narrowband filter. Moreover, for the Fano-like absorption, the electrical field distribution in the structure is also calculated to investigate the influence of the wavelength detuning of “atom 2” from that of “atom 1”. Figures 6(c) and 6(d) show the electrical field distributions for the absorption peaks in Fig. 6(a) with Lorentzian and Fano-like shapes, respectively. It is observed that the confinement area of electrical field has obviously been changed from the cavity close to the graphene layer to a more distant one. This confirms that the EIT-like or the Fano-like absorption peak is formed through the interference between the two cavities of “atom 1” and “atom 2”. The huge electrical field enhancement with a magnitude of over 1.4×104 means the SERS enhancement factor beyond of 3.8×1016, which can be potentially applied for single-molecule detection.33

Fig. 6. The A, R, and T spectra and the electrical field distributions: (a) spectra for structure EG(BC)2 with single Fano-like absorption peak; (b) spectra for structure EG(BC)6 with five Fano-like absorption peaks; (c) and (d) the electrical field distributions corresponding to the absorption peaks in (a) with Lorentzian and Fano-like shapes. Each layer of EG(BC)2 is marked with different colors from the left to the right. Structure parameters include nprism=nb=3.48, db=120nm, nc=1.55, dc=269nm, ne=1.23, and de=100nm.

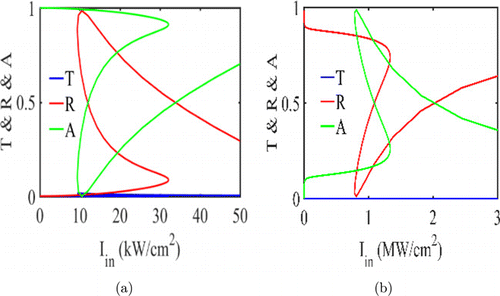

Furthermore, when the nonlinear property of the material is considered, the bistable absorption can be obtained.34 Figures 7(a) and 7(b) show the nonlinear performances in the cases of EIT-like and Fano-like absorption, respectively. Obviously, the bistable behaviors are observed for both the absorption and reflection curves. As shown in Fig. 7(a), with a set of suitable structure parameters, the absorption dip of the EIT-like absorption occurs at λ=1118nm. With increased input light intensity, a nearly zero (∼10−4) absorption arrives at threshold about 10kW/cm2. Whereas, in Fig. 7(b), the complete absorption arrives at λ=670.53nm with a threshold of 0.8MW/cm2. The much low bistable thresholds show their great potential advantages for the design of all optical switching and logical circuits.

Fig. 7. The nonlinear performance of structure EGBCBC: (a) at λ=1120nm with structure parameters nprism=nb=3.48, db=200nm, nc=1.55, dc=400nm, ne=1.55, and de=185nm; (b) at λ=670.53nm with structure parameters shown in Fig. 6(a). The nonlinear refractive index of layer C is nc2=2.5×10−15m2/W in both calculations.

In principle, the EIT and the Fano-like absorption also can be theoretically explained by the coupled mode model. For the structure of EG-(BC)N+1, the N individual “atoms” are characterized by the energy amplitudes of the cavities which are denoted by the energy amplitude array a= [a1,a2, …, aN−1, aN]T, where aq (q=1,…, N) represents the energy amplitude in the qth cavity. We assume that the input power is Pin, then the input array s= [−jμiP1∕2i, 0, …, 0, 0]T. The time evolution of the energy amplitude a(t) has the following form35 :

By using Eq. (7), for a typical system with three coupled cavities, Fig. 8 exhibits an EIT-like absorption with two tips, agreeing well with the result in Fig. 4(a). It demonstrates that this model can also be used for inverse design. That is, for a given line shape calculated by the transfer matrix method, the coupling coefficients and the detuning wavelength of the individual cavity in a coupled resonator structure can be fitted and extracted by the coupled mode model. This builds a link between the desired spectral property and the geometric parameters for the design of the device with the characteristic of EIT-like absorption. This can be potentially applied for absorption-based imaging as targets with varied refractive index response can be located in the buffer or B sensing layer.

Fig. 8. Absorption of a system with three cavities. The simulation parameters are set as QL,1=5×104, QL,2=1×108, QL,3=1×108, Qi=2×103, and Qc,1=Qc,2=Qc,3=2×104.

It should be clarified at this point that the captioned manuscript focuses on numerical simulation as the first step of the project to make sure of the feasibility and optimum design. That said, experiments have been planned and under preparation. In the following, the fabrication of the structure is briefly discussed herein. For multiple graphene layers, researches have reported the realization of enhanced absorption between two dielectric materials.23 For monolayers, there are studies positioning the graphene monolayer in a microcavity to form a photodetector,3,36 which may be used as reference in fabrication. Specifically, when silicon and air materials are used (e.g., Figs. 1–5), the silicon-air filter can be fabricated using the method in Ref. 37. The graphene monolayer can also be fabricated through a suspended structure.38 When other dielectric materials are used (e.g., Fig. 6), the multiple dielectric layers can be fabricated through plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD)3,39 or spin-coating.32

Note that imperfections, such as twisted or folded regions, are inevitable during fabrication, which will reduce the performance of the spectrum response obtained in numerical simulation. That said, recent developments in the field have allowed for fabrication of large-area continuous and uniform graphene monolayers.40,41 For example, graphene monolayers of ∼3.5×1.5cm2 have been achieved.40 Lastly, but not the least, the following dielectric material parameters will be considered in fabrication: for the silicon-air configuration in near-infrared as shown in Figs. 1–5, silicon with n=3.48 will be used for prism and B layer (E, F, and C layers are air);42 for the multiple dielectric layers in Fig. 6, SiO2 (quartz) with n=1.55 will be used for B layer, but nanoporous SiO2 with a low-refractive-index material n=1.23 [44] will be used for C layer;43 for nonlinear application in Fig. 7, silicon with n=3.48 will be used for prism and B layer, and polydiacetylene 9-BCMU organic material with n=1.55 and high nonlinear coefficient nc2 will be used for C layer.45

4. Conclusions

In summary, to achieve tunable absorptions characteristics for biosensing, a buffer-graphene-1DPC multilayer structure is proposed to obtain the EIT-like and the Fano-like absorptions in the near-infrared regime. The absorption property of the structure can be tuned by changing the geometric or physical parameters of the designed configuration and the incident angle of light. The tunable multichannel EIT-like and Fano-like absorptions may be applied for designing of various biosensing devices, such as sensor, filter, modulator, optical tagging, thermal detecting, optical switching and all-optical diode.46,47,48 Moreover, the structure with EIT-like and Fano-like absorption in visible and near-infrared regimes can potentially be extended to infrared and even terahertz spectrum for more applications in biosensing.

Acknowledgments

National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81671726, 81930048, 81627805, 61675104); Hong Kong Research Grant Council (25204416); Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission (ITS/022/18); Guangdong Science and Technology Commission (2019A1515011374); Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (JCYJ20170818104421564).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.