Cookies Notification

|

System Upgrade on Tue, May 28th, 2024 at 2am (EDT)

Existing users will be able to log into the site and access content. However, E-commerce and registration of new users may not be available for up to 12 hours.For online purchase, please visit us again. Contact us at customercare@wspc.com for any enquiries.

Advanced Series in Biomechanics: Volume 4

An Introductory Text to Bioengineering

- Edited by:

- Shu Chien (University of California, San Diego, USA),

- Peter C Y Chen (University of California, San Diego, USA), and

- Y C Fung (University of California, San Diego, USA)

This ebook can only be accessed online and cannot be downloaded. See further usage restrictions.

This bestselling textbook will introduce undergraduate bioengineering students to the fundamental concepts and techniques, with the basic theme of integrative bioengineering. It covers bioengineering of several body systems, organs, tissues, and cells, integrating physiology at these levels with engineering concepts and approaches; novel developments in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, nanoscience and nanotechnology; state-of-the-art knowledge in systems biology and bioinformatics; and socio-economic aspects of bioengineering.

One of the distinctive features of the book is that it is integrative in nature (integration of biology, medicine and engineering, across different levels of the biological hierarchy, and basic knowledge with applications). It is unique in that it covers fundamental aspects of bioengineering, cutting-edge frontiers, and practical applications, as well as perspectives of bioengineering development. Furthermore, it covers important socio-economical aspects of bioengineering such as ethics and entrepreneurism.

Sample Chapter(s)

Chapter 1: Overview (58 KB)

Chapter 2: Perspectives Of Biomechanics (1,919 KB)

Chapter 3: Cardiac Electromechanics in the Healthy Heart (2,681 KB)

Chapter 5: Bioengineering Solutions for the Treatment of Heart Failure (60 KB)

Chapter 15: Multi-Scale Biomechanics Ofarticular Cartilage (625 KB)

Contents:

- Perspectives of Biomechanics (Y-C B Fung & W Huang)

- Cardiac Electromechanics in the Healthy Heart (R C P Kerckhoffs & A D McCulloch)

- Cardiac Biomechanics and Disease (J H Omens)

- Bioengineering Solution for the Treatment of Heart Failure (J T Watson & S Chien)

- Molecular Basis of Modulation of Vascular Functions by Mechanical Forces (S Chien)

- Autoregulation of Blood Flow: Examining the Process of Scientific Discovery (P C Johnson)

- Molecular Basis of Cell and Membrane Mechanics (L A Sung)

- Cell Activation in the Circulation: The Auto-Digestion Hypothesis (G W Schmid-Schönbein)

- Blood Substitutes and the Design of Oxygen Non-Carrying and Carrying Fluids (M Intaglietta)

- Analysis of Human Pulmonary Circulation: A Bioengineering Approach (W Huang et al.)

- Pulmonary Gas Exchange (P D Wagner)

- Engineering Approaches to Understanding the Kidney (S C Thomson)

- Skeletal Muscle Tissue Bioengineering (R L Lieber & S R Ward)

- Multi-Scale Biomechanics of Articular Cartilage (W C Bae & R L Sah)

- Design and Development of an In Vivo Force-Sensing Knee Prosthesis (D D D'Lima & P C Y Chen)

- The Implantable Glucose Sensor in Diabetes: A Bioengineering Case Study (D A Gough)

- Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine (S Chien & L S B Goldstein)

- Engineering Compounds Targeted to Vascular Zip Codes (E Ruoslahti)

- The Structure of the Central Nervous System and Nanoengineering Approaches for Studying and Repairing It (G A Silva)

- Cellular Biophotonics: Laser Scissors (Ablation) (M W Berns)

- Microelectronic Arrays: Applications from DNA Hybridization Diagnostics to Directed Self-Assembly Nanofabrication (M J Heller & D Dehlinger)

- Systems Biology: A Four-Step Process (J L Reed & B O Palsson)

- Bioinformatics and Systems Biology: Obtaining the Design Principles of Living Systems (S Subramaniam)

- Synthetic Biology: Bioengineering at the Genomic Level (N Ostroff et al.)

- Network Genomics (T Ideker)

- Genomes, Genomic Technologies and Medicine (X Huang)

- Ethics for Bioengineers (M Kalichman)

- Opportunities and Challenges in Bioengineering Entrepreneurship (J-S Lee)

- How to Move Medical Devices from Bench to Bedside (P Citron)

Readership: Bioengineering undergraduates and students from other engineering and biomedical disciplines who are interested in having an overview of the discipline of bioengineering; postdoctoral fellows, research scientists, faculty and scientists in industry, government and other institutions.

FRONT MATTER

- Shu Chien,

- Peter C Y Chen, and

- Y C Fung

- Pages:i–xix

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_fmatter

The following sections are included:

- CONTENTS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SECTION I: INTRODUCTORY CHAPTERS

OVERVIEW

- Pages:3–12

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0001

As indicated in the Preface, the theme of this book is Integrative Bioengineering, which brings together the fundamental concepts and techniques in engineering and biomedical sciences and demonstrates their interplays. It is organized in a cohesive manner to facilitate learning and to stimulate innovation. There are eight sections that are composed of 30 chapters. Section I is introductory in nature, and it is followed by Secs. II to IV that cover the bioengineering of several organ systems, with a close relation to physiology, i.e. Cardiovascular Bioengineering, Blood Cell Bioengineering, and Respiratory-Renal Bioengineering. Sections V to VII present three new areas of developments in bioengineering, viz. Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine, Nanoscience & Nanotechnology, and Genomic Engineering & Systems Biology. The last section (VIII) addresses the important socio-economical aspects of bioengineering.

PERSPECTIVES OF BIOMECHANICS

- Pages:13–33

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0002

Biomechanics is mechanics applied to biology. It covers a very wide territory. In this chapter, the use of biomechanics in bioengineering is illustrated with a few examples on tissue remodeling in blood vessels. Our objective is to demonstrate how theory and experiment couple together, and how design and science do link in biomechanics.

SECTION II: CARDIOVASCULAR BIOENGINEERING

CARDIAC ELECTROMECHANICS IN THE HEALTHY HEART

- Pages:37–52

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0003

In this chapter, cardiac function is discussed in the context of the healthy heart as part of a system. Anatomy and physiology will be described for each scale, starting with the organ level, and continuing to tissue and cell scales. For each scale, we will have a closer look at both electrical and mechanical functions.

Electrical function in the heart is intimately linked to mechanical function: muscle contraction is generated at the cellular level, and triggered by electrical activity via the flux of calcium ions. Furthermore, cell electrophysiology is modified by feedback from mechanical alterations (mechano-electric feedback or MEF). From a clinical standpoint, understanding these electromechanical interactions is becoming increasingly important because, for example, of regional wall remodeling induced by chronic pacing and the rapidly growing interest in cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT).

As electrophysiology and mechanics in the heart are virtually inseparable, so are experiment and mathematical models of cardiac bioengineering. Through iterative interactions between experiment and simulation, insight in cardiac physiology is growing. Hence, in this chapter we will refer to examples of bioengineering experiments and simulations that helped in understanding normal cardiac function. The role of mechanics in cardiac disease can be found in Chapter 4.

CARDIAC BIOMECHANICS AND DISEASE

- Pages:53–68

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0004

Biomechanics plays a central role in research of the heart and its function, fundamentally because the main role of the heart as an organ is the mechanical pumping of blood through the circulation of the body. Diseases of the heart are many times a direct consequence of impaired mechanics. Although quantifying cardiac function in the normal and diseased heart can be as simple as determining the cardiac output, i.e. the amount of blood pumped per unit time, the underlying structure and function of this organ are very complex, and scientific investigations encompass experimental procedures on the intact organ, muscle tissue and cardiac muscle cells, as well as roles of individual proteins within the cells and extracellular matrix. Cardiac biomechanics examines not only the structural basis of tissue stress development and global function, but also how cells and tissue respond to external loads. The normal response of the heart to increases in stress is hypertrophy (growth) of the cells and tissue, but defects in the transduction of the mechanical signals can lead to inadequate compensatory growth, and in many cases failure of the mechanical pump.

BIOENGINEERING SOLUTIONS FOR THE TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE

- Pages:69–77

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0005

For the last 50 years, deaths from cardiovascular disease have steadily declined. The major exception is heart failure (HF), which is a disease condition where the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the metabolic requirements of the patient's body. HF has steadily increased over the last 50 years for both men and women of all races. This chapter discusses HF as a public health problem and a bioengineering solution for reversing this condition and restoring the patients' cardiac function. Design principles are presented for mechanical circulatory support systems, including ventricular assist devices and heart replacements or total artificial hearts.

MOLECULAR BASIS OF MODULATION OF VASCULAR FUNCTIONS BY MECHANICAL FORCES

- Pages:79–97

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0006

Mechanical forces such as shear stress can modulate gene and protein expressions and hence cellular functions by activating membrane sensors and intracellular signaling. Studies on cultured endothelial cells have shown that laminar shear stress causes a transient increase in MCP-1 expression, which involves the Ras-MAP kinase signaling pathway. We have demonstrated that integrins and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor Flk-1 can sense shear stress, with integrins being upstream to Flk-1. Other possible membrane components involved in the sensing of shear stress include G-protein coupled receptors, ion channels, intercellular junction proteins, membrane glycocalyx, and the lipid bilayer. Mechanotransduction involves the participation of a multitude of sensors, signaling molecules, and genes. Microarray analysis has demonstrated that shear stress can up- and down-regulate different genes. Sustained shear stress down-regulates atherogenic genes (e.g. MCP-1) and up-regulates growth arrest genes. In contrast, the disturbed flow observed at branch points and induced in step-flow channels causes sustained activation of MCP-1 and the genes that enhance cell turnover and lipid permeability. These findings provide a molecular basis for the explanation of the preferential localization of atherosclerotic lesions at regions of disturbed flow, such as the arterial branch points, and the sparing of the straight part of the arterial tree. The combination of mechanics and biology (from molecules- cells to organs-systems), can help to elucidate the physiological processes of mechano-chemical transduction and improve the management of important clinical conditions such as coronary artery disease.

AUTOREGULATION OF BLOOD FLOW: EXAMINING THE PROCESS OF SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY

- Pages:99–113

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0007

Autoregulation of blood flow is the tendency for blood flow to remain constant in an organ during changes in arterial perfusion pressure. It is due to local mechanisms in the organ and is independent of the regulatory mechanisms of the central nervous system. The possible explanations that have received the most attention are the metabolic and myogenic hypotheses. We review the experimental evidence for and against these hypotheses both to develop our understanding of autoregulation and as examples of the process of scientific inquiry. Evidence is presented in support of the metabolic hypothesis that autoregulation is due to a link between blood flow and energy metabolism but the lack of definitive evidence for most proposed mediators is noted. The myogenic response has been more controversial since it proposes that the arterioles regulate flow indirectly by constricting in response to intravascular pressure as a stimulus. The possible involvement of integrins and stretch sensitive channels in this response is described. Autoregulation may be important in clinical situations such as atherosclerosis and blood loss. Reviewing the development of our understanding of autoregulation provides insight to the manner in which concepts arise and are tested experimentally.

SECTION III: BLOOD CELL BIOENGINEERING

MOLECULAR BASIS OF CELL AND MEMBRANE MECHANICS

- Pages:117–129

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0008

To understand the molecular basis of cell and membrane mechanics, we cloned cDNAs that encode red blood cell membrane skeletal proteins. Characterizing genomic organization allowed us to disrupt a target gene in an embryonic stem cell and create knockout mouse models. Such models allowed us to establish the precise relationship between a molecular defect and mechanical changes of single cells by experiments. We expressed recombinant proteins and mapped their binding sites. From protein-protein interaction we constructed the first three-dimensional model for a junctional complex and explained how the junctional complex may, in turn, dictate the network topology of the membrane skeleton. The 3-D nano-mechanics of the red cell membrane skeleton may now be understood at the molecular level by simulation.

CELL ACTIVATION IN THE CIRCULATION: THE AUTO-DIGESTION HYPOTHESIS

- Pages:131–148

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0009

In this chapter we present an idea for a 21st century biomedical engineer: get involved in the engineering analysis of an important human disease. There are many diseases that need attention and few have been subjected to a rigorous engineering analysis. The purpose of an engineering analysis is to find out what goes on and why an organ or a tissue fails. A good medical intervention is then based on such a rigorous engineering analysis. The time is right to start such an effort. I will illustrate the beginnings of an approach in one of the most lethal conditions, shock and multi-organ failure.

BLOOD SUBSTITUTES AND THE DESIGN OF OXYGEN NON-CARRYING AND CARRYING FLUIDS

- Pages:149–159

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0010

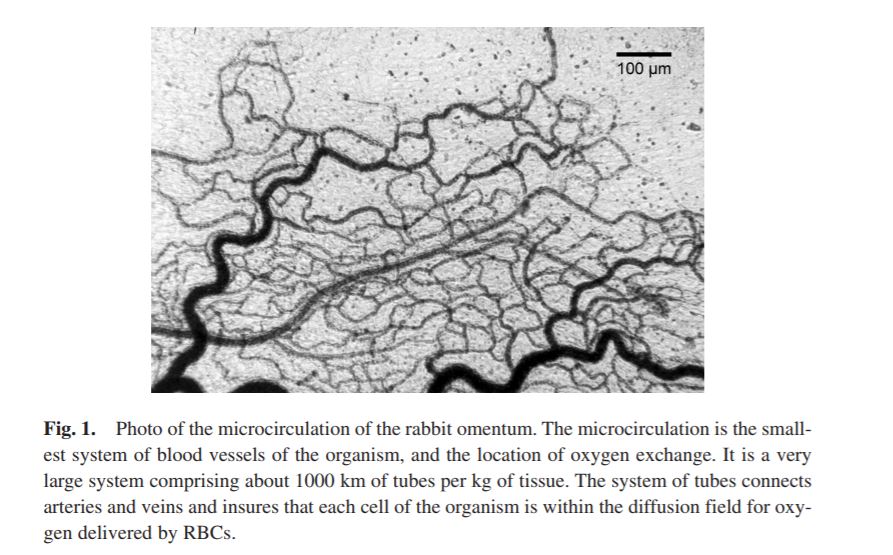

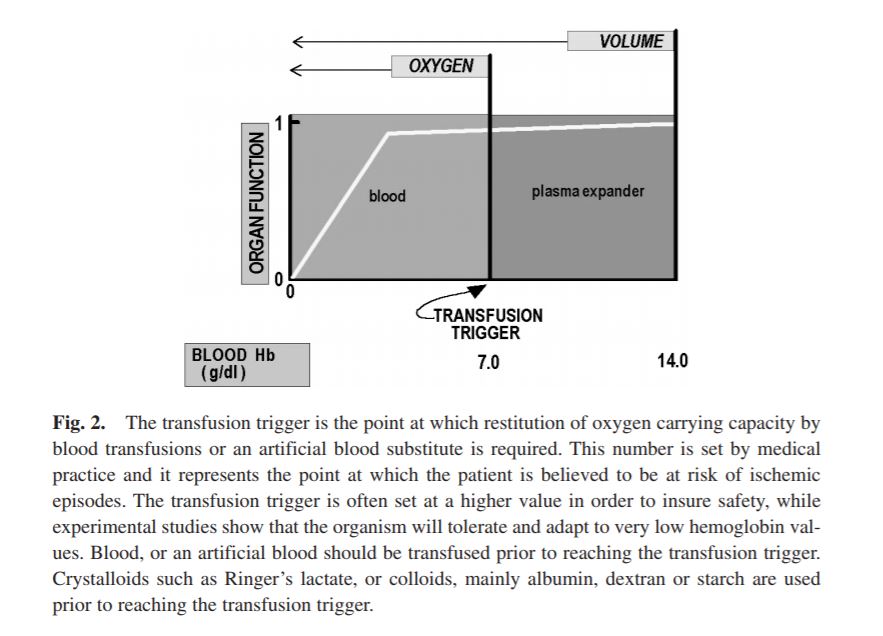

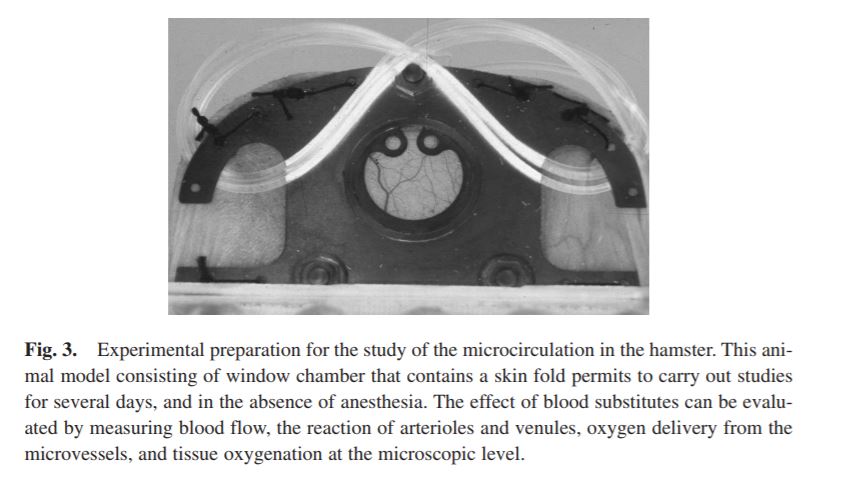

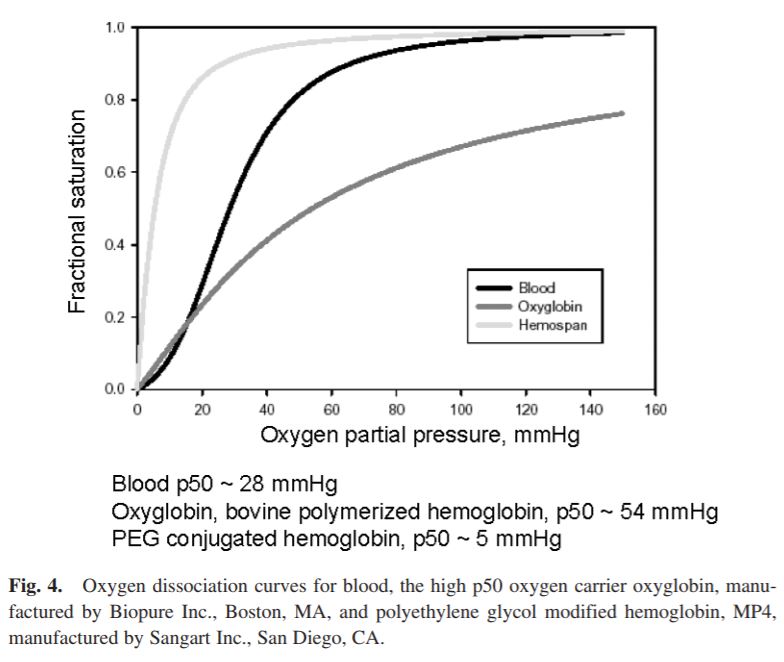

Analysis of oxygen transport at the level of microscopic blood vessels has resulted in the development of blood substitutes with novel properties that are different from blood. These include a high oxygen affinity, which targets oxygen delivery to tissue regions with low pO2, and a high viscosity, which insures the maintenance of functional capillary density in conditions of extreme anemia. These materials are based on the conjugation of polyethylene glycol with molecular hemoglobin, and are effective in treating hemorrhage and extreme hemodilution at low concentration, providing a realistic re-deployment of existing resources of human blood.

SECTION IV: RESPIRATORY-RENAL BIOENGINEERING

ANALYSIS OF HUMAN PULMONARY CIRCULATION: A BIOENGINEERING APPROACH

- Pages:163–180

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0011

This chapter presents a bioengineering approach to study human pulmonary circulation based on the principles of continuum mechanics in conjunction with detailed measurements of pulmonary vascular geometry, vascular elasticity, and blood rheology. Experimental data are used to construct a mathematical model of pulsatile flow in the human lung. Input impedance of every order of pulmonary blood vessels is calculated under physiological condition, and pressure-flow relation of the whole lung is predicted theoretically. The influence of variations in vessel geometry and elasticity on impedance spectra is analyzed. The goal is to understand the detailed pulmonary blood pressure-flow relationship in the human lung for clinical application.

PULMONARY GAS EXCHANGE

- Pages:181–207

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0012

This chapter describes how the lungs perform their principal task — the uptake of O2 from the air into the blood, and the simultaneous movement of CO2 from the blood to the air. The unique structure of the lungs as 300 million separate alveoli (300 μm diameter gas-filled spaces whose walls are essentially made of capillary networks) facilitates this exchange through a linked series of transport functions that employ both convective and diffusive movements of gas. The alveoli lie at the distal ends of a complex branching network of hollow airways much as grapes connect to a stalk. The alveolar wall capillaries are fed by a similar, branching pulmonary arterial tree, and are drained by corresponding pulmonary veins. Ventilation (a convective process) brings O2 from the air to the alveoli during inspiration, while during expiration the gas in the alveoli is moved back to the outside air by flow reversal through the same airways to eliminate CO2. The two gases exchange between blood and air in the alveoli by diffusion. This avoids energy expenditure and accounts for the very large number of very small exchange units, a strategy that greatly increases surface area without also requiring a large lung volume. The third process is blood flow, again convective, that moves the blood out of the alveolar capillaries and back to the left heart for distribution to the tissues. These three transport functions are well-understood and can be modeled mathematically with remarkable accuracy using simple mass conservation principles. The lung is the only organ whose major function can be described and thus understood adequately in terms of such simple transport equations, as this chapter shows. More complete descriptions can be found in the references,1–6 which are intended for further reading for those interested in additional details.

ENGINEERING APPROACHES TO UNDERSTANDING THE KIDNEY

- Pages:209–222

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0013

In this chapter, kidney physiology is singled out as an exemplar of how engineering methods shape the laws of motion, thermodynamics, and control theory into applicable techniques for the biologist. It is the role of kidneys to stabilize the volume and composition of the body fluids against outside disturbance. This is accomplished by generating a large volume of ultrafiltrate from plasma in the renal glomeruli, then subjecting the ultrafiltrate to extensive modification by the renal tubules to form a final urine that matches the dietary intake. A brief overview is provided of the various kidney functions, followed by a description of how engineering approaches have been central to our understanding of glomerular ultrafiltration, basic tubular reabsorption, the countercurrent multiplier system for enabling a concentrated urine, and internal negative feedback controllers that stabilize kidney function.

SECTION V: TISSUE ENGINEERING AND REGENERATIVE MEDICINE

SKELETAL MUSCLE TISSUE BIOENGINEERING

- Pages:225–241

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0014

Skeletal muscle represents a classic biological example of a structure-function relationship. Skeletal muscle anatomy can be determined using a combination of direct tissue dissection and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Whole muscle force is determined primarily by the orientation and number of fibers within the muscle, known as skeletal muscle architecture. Within muscle fibers, sarcomere arrangement determines muscle fiber force generated. These sarcomeres are very sensitive to both length and velocity and must be incorporated into any model that attempts to predict muscle force during normal function.

MULTI-SCALE BIOMECHANICS OF ARTICULAR CARTILAGE

- Pages:243–260

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0015

Articular cartilage is a connective tissue that covers the ends of bones in the body, bearing and transmitting load while allowing low-friction and low-wear joint articulation. The biomechanical functions of articular cartilage have been examined at multiple length scales, ranging from intact joints to cellular and molecular components. The objective of this chapter is to provide an introduction to (1) the composition, structure, and function of articular cartilage, (2) biomechanical tests of articular cartilage, and consideration of the uses, configurations, and length scales of such tests, and (3) mathematical analysis of tissue deformation and strain. The knowledge gained from such multi-scale biomechanical studies facilitates the understanding of cartilage function in growth, aging, health and disease.

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF AN IN VIVO FORCE-SENSING KNEE PROSTHESIS

- Pages:261–278

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0016

Understanding the origin and distribution of tibiofemoral forces is essential in the design and development of total knee replacement prostheses because these forces determine the fit, wear, and long-term outcome of the prosthesis. A total knee replacement tibial tray component with four embedded force transducers and a telemetry system was developed to directly measure tibiofemoral compressive forces in vivo. The design underwent many modifications since 1993 and has been tested extensively in the laboratory to determine performance, accuracy, and safety. Trial surgical implantation was performed to demonstrate feasibility and to test the utility of the prosthesis as a dynamic ligament balancing device, which is an essential measure for proper alignment and success of the operation. Dr. Clifford Colwell Jr. performed the first permanent surgical implantation on February 27, 2004 and in vivo tibial forces were recorded for the first time in history. Knee forces were monitored during recovery and rehabilitation in the early period after surgery, as well as for activities of daily living and exercise over the first 12 months after surgery. These data were supplemented with video motion analysis, electromyography, and ground reaction force measurement. The data will provide the necessary information for the orthopedic scientific community to improve knee prostheses designs.

THE IMPLANTABLE GLUCOSE SENSOR IN DIABETES: A BIOENGINEERING CASE STUDY

- Pages:279–290

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0017

Diabetes is a devastating disease that is rapidly becoming more prevalent worldwide. All approaches to therapy in diabetes are based on management of blood glucose, and there is a need for a broadly acceptable sensor to continuously monitor glucose. This chapter describes the rationale for new glucose sensors and how they would be used, and reviews our recent work on development of a long-term implantable sensor. Diabetes is an area where there are many opportunities to employ the powerful tools of bioengineering.

STEM CELLS IN REGENERATIVE MEDICINE

- Pages:291–309

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0018

Stem cells can either self-renew for long periods without differentiation or can become differentiated under specific conditions into specialized cells. They have great potential to treat disease someday by regenerating the dysfunctional cells or by providing novel ways to develop either drugs or other therapies. Embryonic stem cells from blastocysts are pluripotent in that they can differentiate into all types of cells in any organ/tissue. Adult stem cells, which are present in small proportions in organs/tissues after birth, are thought to be multipotent in that they differentiate only into the types of cells that exist in the organ/tissue in which they reside. There is some evidence that adult stem cells might become pluripotent and trans-differentiate into cells of other organs/tissues, but this evidence need replication. Currently, human embryonic stem cells hold great promise for medical advances in treating diseases, but there have been some objections to using cells from a blastocyst due to moral and religious considerations. The critical issues are whether undifferentiated blastocysts should be thought of as being a person and how do we balance potential life and existing adult life. New methods are being developed to produce pluripotent stem-cell lines with the aim of circumventing such objections based on religious, ethical and/or political grounds. There is much to be done in research on stem cells in order to realize their maximum benefits in clinical applications. Bioengineers can play a significant role in fostering the advance of stem cell research and applications.

SECTION VI: NANOSCIENCE AND NANOTECHNOLOGY

ENGINEERING COMPOUNDS TARGETED TO VASCULAR ZIP CODES

- Pages:313–325

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0019

The blood vessels in different tissues carry specific molecular markers. Various disease processes, such as cancer, inflammation or atherosclerosis, express their own molecular markers on the vasculature. These tissue- and disease-specific molecules create a “zip code” system of vascular addresses. The vascular addresses for tissues and disease processes reside in the inner lining of the blood vessels, the endothelium, and are thus readily accessible from the blood stream. The screening of phage-displayed peptide libraries in vivo has been a particularly effective way of identifying vascular zip codes. Targeting a drug to these addresses can enhance the efficacy of the drug while reducing its side effects. The greatest potential of the vascular targeting technology may be in constructing smart nanodevices.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM AND NANOENGINEERING APPROACHES FOR STUDYING AND REPAIRING IT

- Pages:327–351

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0020

Nanotechnologies involve materials and devices with an engineered functional organization at the nanometer scale. Applications of nanotechnology to cell biology and physiology provide targeted interactions at a fundamental molecular level. In neuroscience, this entails specific interactions with neurons and glial cells, which complements the cellular and molecular organization and structure of the nervous system. Examples of current work include technologies designed to better interact with neural cells, advanced molecular imaging technologies, applications of materials and hybrid molecules for neural regeneration and neuroprotection, and targeted delivery of drugs and small molecules across the blood-brain barrier.

CELLULAR BIOPHOTONICS: LASER SCISSORS (ABLATION)

- Pages:353–367

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0021

This chapter examines the use of light (photons) at the tissue and cellular levels and is focused towards achieving an understanding and application of light to bioengineering and medical problems. Initial discussion focuses on the mechanisms of photon interaction at the tissue and cellular levels. These are of a thermal, mechanical, and chemical nature. Examples are given for the eye because it is the organ that is the most studied and manipulated by light. The use of light for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer particularly related to the use of light-sensitive photochemical agents is presented (photodynamic therapy). At the cellular and sub-cellular level the use of a laser microbeam is discussed. Particular interest is focused on the use of the laser microbeam to manipulate the organelles of the dividing cell. The advent of the GFP gene-fusion proteins and their use in facilitating the visualization and targeting of sub-cellular structures is recognized. The combined use of cell tracking and robotics in the devlopment of an Internet-based laser microscope is also discussed.

MICROELECTRONIC ARRAYS: APPLICATIONS FROM DNA HYBRIDIZATION DIAGNOSTICS TO DIRECTED SELF-ASSEMBLY NANOFABRICATION

- Pages:369–384

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0022

A variety of microelectronic array devices have been developed for DNA hybridization analysis and clinical genotyping diagnostics. In addition to these DNA research and diagnostic applications, such devices are now being used to carry out layer-by-layer (LBL) directed self-assembly of a wide variety of molecular and nanoparticle entities into higher order structures. Such microelectronic array devices are able to produce electric fields on their surfaces that allow charged molecules and nanostructures to be rapidly transported and bound to any site on the surface of the array. Such devices can utilize either DC electric fields which affect the electrophoretic transport of the entities, or AC electric fields which allows entities to be selectively positioned by dielectrophoresis (DEP). In the past, microelectronic array devices have been used to carry out the selective transport and binding of DNA, RNA, peptides, proteins, nanoparticles, cells and even micron scale semiconductor components. More recently, these devices have demonstrated the ability to carry out the directed self-assembly of biotin and streptavidin derivatized nanoparticles into multilayer structures. Nanoparticle addressing can be carried out in about 15 seconds, and more than 40 nanoparticle layers can be completed in less than one hour. Microelectronic array based directed self-assembly represents an example of combining “top-down” and “bottom-up” technologies into viable nanofabrication process for the assembly and integration of nanocomponents into higher order structures.

SECTION VII: GENOMIC ENGINEERING AND SYSTEMS BIOLOGY

SYSTEMS BIOLOGY: A FOUR-STEP PROCESS

- Pages:387–399

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0023

Systems biology focuses on the study of biological networks through the processes of network reconstruction, computer model formulation, hypothesis generation and experimentation. This chapter sets out to define systems biology and the technological driving forces that have enabled the field to emerge. In addition, the four core steps in systems biology are presented. The first two steps involve identifying components in biological networks and interactions between these components. The result of the first two steps is a network reconstruction: an accounting of all components and their interactions compromising the network. From this network reconstruction, an in silico model can be generated (step 3) which can be used to predict and analyze the behavior of biological systems (step 4). The chapter concludes with a discussion of systems biology applications, to address specific biological and industrial questions.

BIOINFORMATICS AND SYSTEMS BIOLOGY: OBTAINING THE DESIGN PRINCIPLES OF LIVING SYSTEMS

- Pages:401–426

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0024

All living systems obey the principal laws of nature, including the laws of thermodynamics. However, an important feature characterizes living systems. Because of the need for living systems to self-organize and self-evolve, the coupling between multiple time scales or multiple length scales are non-hierarchical. For instance, the absorption of a photon with a primary event happening in femptosecond time scales leads to long time-scale processes to result in vision. Events that happen in seconds and minute time scales give rise to developmental processes that happen in days to weeks. Also processes that can be traced to events in a single cell can result in a systemic response spanning entire physiology. The blueprint for continuous adaptation, error-checking and optimization of the system is built into living systems such that they sample infinite number of states with no two states being identical. Yet the end-point physiology is often similar or in some cases identical. This implies that multiple solutions lead to nearly the same optimality and behavior of the system. In this chapter we will explore the features of living systems from an engineering and design perspective and attempt to identify methods we can use to decipher the rules that govern living systems.

SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY: BIOENGINEERING AT THE GENOMIC LEVEL

- Pages:427–451

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0025

The developing discipline of synthetic biology attempts to recreate in artificial systems the emergent properties found in natural biology. Because the genetic networks found in cells are often highly integrated and quite complex, redesigning simpler synthetic systems for study is a valuable approach not only at the genome level but also at the gene network level. Recently, there has been significant activity directed towards designing synthetic gene networks that mimic the functionality of natural systems. In addition to being easier to construct, the reduced complexity and increased isolation of these networks makes them more amenable to both tractable experimentation and mathematical modeling. The process of constructing and testing artificial systems resembling naturally occurring systems promises to advance our understanding of how biological systems function by providing information about cellular processes that cannot be obtained by studying intact native systems.

NETWORK GENOMICS

- Pages:453–471

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0026

Network Genomics is an emerging area of bioengineering which models the influence of genes (hence, genomics) in the context of a larger biomolecular system or network. A biomolecular network is a comprehensive collection of molecules and molecular interactions that regulate cellular function. Molecular interactions include physical binding events between proteins and proteins, proteins and DNA, or proteins and drugs, as well as genetic relationships dictating how genes combine to cause particular phenotypes. Thinking about biological systems as networks goes hand-in-hand with our ability to experimentally measure and define biomolecular interactions at large scale. Once we have catalogued all of the interactions present in a network, we may begin to ask questions such as: “How many different molecules are bound by a typical protein?” “What is the topological structure of the network?” “How are signals transmitted through the network in response to internal and external events?”; “Which parts of the network are evolutionarily conserved across species, and which parts differ?” Perhaps most importantly, we can begin to use the interaction network as a storehouse of information from which to extract and construct computer-based models of cellular processes and disease.

GENOMES, GENOMIC TECHNOLOGIES AND MEDICINE

- Pages:473–485

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0027

The genome is the blueprint of life for all organisms. It encodes in digital form all the hereditary instructions for building, running, maintaining and reproducing an organism. The sequencing of the human genome was one of the greatest breakthroughs in biology and medicine in the last century. With the human genome sequence, scientists can now attempt to enumerate the genes encoding the proteins that form and operate the molecular circuitries in the cells. Genome sequencing with currently available technologies, however, remains slow and expensive for the routine sequencing of individual human genomes for many biomedical applications. For example, sequencing the genomes of a large number of individuals would allow us to examine all the genetic differences in the human populations to search for the genetic basis of complex traits, to perform association studies to identify the molecular etiology of a variety of diseases, and to study human evolution. Identifying the causal genes and variants would represent a significant step towards improved diagnosis, prevention and treatment of diseases. This chapter describes our strategies and recent progresses in engineering the next generation technologies for genome sequencing and for digital enumerations of the molecular components in the cells. In the new technological paradigm we are creating, micro- and nano-technologies are used to engineer fully automated miniaturized “lab-on-a-chip” devices to enable massive parallel manipulations and analyses of biological molecules on an unprecedented scale so that each individual human genome can be sequenced for as little as US$1000.

SECTION VIII: SOCIO-ECONOMICAL ASPECTS OF BIOENGINEERING

ETHICS FOR BIOENGINEERS

- Pages:489–506

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0028

It seems that the news media are filled daily with examples of “ethical violations,” “misconduct,” and “shirking of responsibility.” Although these reports are typically in high profile areas such as politics, sports, and business, there is no reason to assume that scientists and engineers are immune from lapses of good judgment. The goal of much of science and engineering is to generate new knowledge, but this work is typically done behind closed doors. Therefore, the risk of being caught is low and the temptation for misrepresentation is great. However, precisely because of the benefits of this new knowledge, it should be expected that scientists and engineers will be particularly concerned about the integrity of their disciplines. The challenges are to identify the ethical dimensions of the work that we do, to be aware of the tools and resources necessary to avoid the ethical pitfalls, to develop the skills for ethical decision-making, and to be clear about the obligation to act responsibly. Integrity is not just an option or an afterthought, but central to what it means to be an outstanding bioengineer.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES IN BIOENGINEERING ENTREPRENEURSHIP

- Pages:507–520

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0029

The contributions made by biomedical engineering entrepreneurs have led to not only better understanding in biology and medicine, but also better health care for people. In this chapter we first review some of the innovations made by the biomedical engineering industry and viewed by physicians as significance in improving the health of their patients. Two innovations, cardiac pacemakers and hemodialysis, are highlighted to elaborate on their entrepreneurial growth into billion dollar industries. Pointers are offered for readers to evaluate the chance of success for their inventions and to gain insights on the commitment required for entrepreneurship. It is concluded with the heading “Biomedical Engineers Mean Business” to encourage bioengineering students to consider entrepreneurs as their career option when opportunities arise.

HOW TO MOVE MEDICAL DEVICES FROM BENCH TO BEDSIDE

- Pages:521–531

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_0030

Although there are similarities in how any new technology in any industry migrates from Research and Development (R&D) to the ultimate customer, the medical device industry has certain elements that are unique to it. Understanding these factors and accommodating them as an integral part of the business development plan can make the difference between a mere laboratory curiosity and an innovation that serves the needs of seriously ill patients, and at the same time produces financial returns for the industry. We will examine some of these factors in this chapter and address how they relate to the success of the innovation process, as well as the regulatory process and FDA's role and its requirements.

BACK MATTER

- Shu Chien,

- Peter C Y Chen, and

- Y C Fung

- Pages:533–542

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812770011_bmatter

The following sections are included:

- INDEX

Shu Chien joined UCSD in 1988 and became the founding chair of the Department of Bioengineering in 1994. As principal investigator on the Whitaker Foundation Development Award (1993) and Leadership Award (1998), Chien played a major role in establishing UCSD's bioengineering program as one of the top two programs in the country. As founding Director of the Whitaker Institute of Biomedical Engineering at UCSD, he helps foster collaborations among the faculty of UCSD and with research institutes and biomedical companies in San Diego. He has won numerous awards and is a member of the National Academy of Engineering and the Institute of Medicine. Chien co–founded Celladon Corporation and serves as a consultant to Advanced Tissue Sciences and AVIVA Biosciences. He received his M.D. from the National Taiwan University and his Ph.D. in Physiology from Columbia University, where he was a professor from 1969 to 1988.

PETER C Y CHEN works on Adjunct Associate Professor, Institute of Microcirculation, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing China, Project Scientist, Lecturer, Bioengineering in University of California, San Diego, Biomedical Engineer, Shiley Center for Orthopaedic Research and Education, La Jolla and he is the owner of E.H. Mead Instruments, San Diego. He received his BA and PhD from University of California, San Diego. In 2008 he is Distinguished Teaching Award, non-academic senate, University of California, San Diego and Mark Coventry Award on the co-authored paper. He received Teacher of the Year Award, University of California, San Diego, Bioengineering Department in 2005 and Malpighi Gold Award for excellence in the production of an educational motion picture.

Y. C. Fung works on solid mechanics, and has helped to establish the fields of aeroelasticity and biomechanics. He received his BS and MS from the National Central University in China and PhD from the California Institute of Technology. He received the United States Presidential National Medal of Science in the year 2000, and the Founders Awards of the US National Academy of Engineering in 1998.

He was elected a member of the US National Academy of Science in 1992, the US Institute of Medicine in 1991, the US National Academy of Engineering in 1979, the Academy of Science of China in 1994, and the Academia Sinica in 1966. He is Distinguished Alumnus of Caltech, Honorary Member of ASME, and winner of the von Karman Medal (ASCE), Timoshenko Medal (ASME), Poiseuille Medal (ISB), Borelli Medal (ASB), Landis Award (AMS), and Alza Award (BMES).

Sample Chapter(s)

Chapter 1: Overview (58 KB)

Chapter 2: Perspectives Of Biomechanics (1,919 KB)

Chapter 3: Cardiac Electromechanics in the Healthy Heart (2,681 KB)

Chapter 5: Bioengineering Solutions for the Treatment of Heart Failure (60 KB)

Chapter 15: Multi-Scale Biomechanics Ofarticular Cartilage (625 KB)